Working with Executives

10.0 INTRODUCTION

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

Chapter 4 Integration Management

Chapter 9 Human Resources Management Chapter

In any project management environment, project managers must continually interface with executives during both the planning and execution stages. Unless the project manager understands the executive's role and thought process, a poor working relationship will develop. In order to understand the executive–project interface, two topics are discussed:

- The project sponsor

- The in-house representatives

10.1 THE PROJECT SPONSOR

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

2.3 Key Stakeholders

5.1.2 Stakeholders Analysis

For more than two decades, the traditional role of senior management, as far as projects were concerned, has been to function as project sponsors. The project sponsor usually comes from the executive levels and has the primary responsibility of maintaining executive–client contact. The sponsor ensures that the correct information from the contractor's organization is reaching executives in the customer's organization, that there is no filtering of information from the contractor to the customer, and that someone at the executive levels is making sure that the customer's money is being spent wisely. The project sponsor will normally transmit cost and deliverables information to the customer, whereas schedule and performance status data come from the project manager.

In addition to executive–client contact, the sponsor also provides guidance on:

- Objective setting

- Priority setting

- Project organizational structure

- Project policies and procedures

- Project master planning

- Up-front planning

- Key staffing

- Monitoring execution

- Conflict resolution

The role of the project sponsor takes on different dimensions based on the life-cycle phase the project is in. During the planning/initiation phase of a project, the sponsor normally functions in an active role, which includes such activities as:

- Assisting the project manager in establishing the correct objectives for the project

- Providing the project manager with information on the environmental/political factors that could influence the project's execution

- Establishing the priority for the project (either individually or through consultation with other executives) and informing the project manager of the established priority and the reason for the priority

- Providing guidance for the establishment of policies and procedures by which to govern the project

- Functioning as the executive–client contact point

During the initiation or kickoff phase of a project, the project sponsor must be actively involved in setting objectives and priorities. It is absolutely mandatory that the executives establish the priorities in both business and technical terms.

During the execution phase of the project, the role of the executive sponsor is more passive than active. The sponsor will provide assistance to the project manager on an as-needed basis except for routine status briefings.

During the execution stage of a project, the sponsor must be selective in the problems that he or she wishes to help resolve. Trying to get involved in every problem will not only result in severe micromanagement, but will undermine the project manager's ability to get the job done.

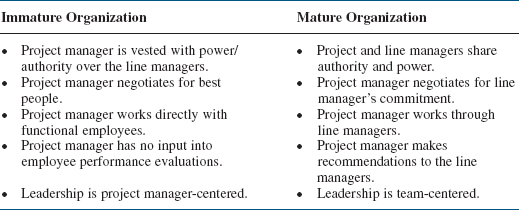

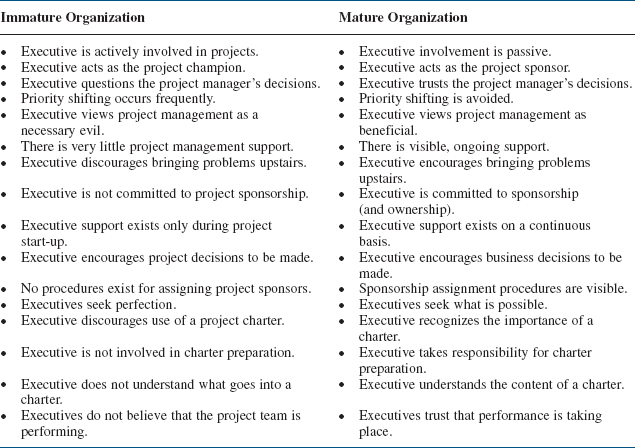

The role of the sponsor is similar to that of a referee. Table 10-1 shows the working relationship between the project manager and the line managers in both mature and immature organizations. When conflicts or problems exist in the project–line interface and cannot be resolved at that level, the sponsor might find it necessary to step in and provide assistance. Table 10-2 shows the mature and immature ways that a sponsor interfaces with the project.

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

1.6 Interpersonal Skills

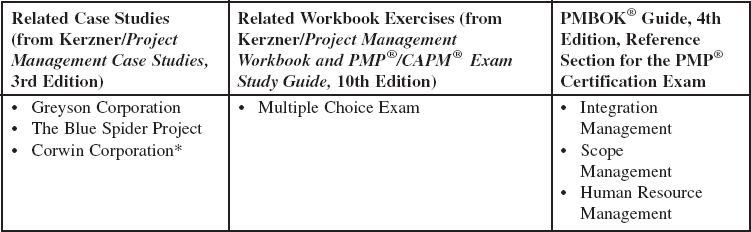

TABLE 10-1. THE PROJECT–LINE INTERFACE

TABLE 10-2. THE EXECUTIVE INTERFACE

It should be understood that the sponsor exists for everyone on the project, including the line managers and their employees. Project sponsors must maintain open-door policies, even though maintaining an open-door policy can have detrimental effects. First, employees may flood the sponsor with trivial items. Second, employees may feel that they can by-pass levels of management and converse directly with the sponsor. The moral here is that employees, including the project manager, must be encouraged to be careful about how many times and under what circumstances they “go to the well.”

In addition to his/her normal functional job, the sponsor must be available to provide as-needed assistance to the projects. Sponsorship can become a time-consuming effort, especially if problems occur. Therefore, executives are limited as to how many projects they can sponsor effectively at the same time.

If an executive has to function as a sponsor on several problems at once, problems can occur such as:

- Slow decision-marking resulting in problem-solving delays

- Policy issues that remain unresolved and impact decisions

- Inability to prioritize projects when necessary

As an organization matures in project management, executives begin to trust middle- and lower-level management to function as sponsors. There are several reasons for supporting this:

- Executives do not have time to function as sponsors on each and every project.

- Not all projects require sponsorship from the executive levels.

- Middle management is closer to where the work is being performed.

- Middle management is in a better position to provide advice on certain risks.

- Project personnel have easier access to middle management.

Sometimes executives in large diversified corporations are extremely busy with strategic planning activities and simply do not have the time to properly function as a sponsor. In such cases, sponsorship falls one level below senior management.

Figure 10-1 shows the major functions of a project sponsor. At the onset of a project, a senior committee meets to decide whether a given project should be deemed as priority or nonpriority. If the project is critical or strategic, then the committee may assign a senior manager as the sponsor, perhaps even a member of the committee. It is common practice for steering committee executives to function as sponsors for the projects that the steering committee oversees.

For projects that are routine, maintenance, or noncritical, a sponsor could be assigned from the middle-management levels. One organization that strongly prefers to have middle management assigned as sponsors cites the benefit of generating an atmosphere of management buy-in at the critical middle levels.

Not all projects need a project sponsor. Sponsorship is generally needed on those projects that require a multitude of resources or a large amount of integration between functional lines or that have the potential for disruptive conflicts or the need for strong customer communications. This last item requires further comment. Quite often customers wish to make sure that the contractor's project manager is spending funds prudently. Customers therefore like it when an executive sponsor supervises the project manager's funding allocation.

FIGURE 10-1. Project sponsorship.

It is common practice for companies that are heavily involved in competitive bidding to identify in their proposal not only the resumé of the project manager, but the resumé of the executive project sponsor as well. This may give the bidder a competitive advantage, all other things being equal, because customers believe they have a direct path of communications to executive management. One such contractor identified the functions of the executive project sponsor as follows:

- Major participation in sales effort and contract negotiations

- Establishes and maintains top-level client relationships

- Assists project manager in getting the project underway (planning, procedures, staffing, etc.)

- Maintains current knowledge of major project activities (receives copies of major correspondence and reports, attends major client and project review meetings, visits project regularly, etc.)

- Handles major contractual matters

- Interprets company policy for the project manager

- Assists project manager in identifying and solving major problems

- Keeps general management and company management advised of major problems

Consider a project that is broken down into two life-cycle phases: planning and execution. For short-duration projects, say two years or less, it is advisable for the project sponsor to be the same individual for the entire project. For long-term projects of five years or so, it is possible to have a different project sponsor for each life-cycle phase, but preferably from the same level of management. The sponsor does not have to come from the same line organization as the one where the majority of the work will be taking place. Some companies even go so far as demanding that the sponsor come from a line organization that has no vested interest in the project.

The project sponsor is actually a “big brother” or advisor for the project manager. Under no circumstances should the project sponsor try to function as the project manager. The project sponsor should assist the project manager in solving those problems that the project manager cannot resolve by himself.

In one government organization, the project manager wanted to open up a new position on his project, and already had a woman identified to fill the position. Unfortunately, the size of the government project office was constrained by a unit-manning document that dictated the number of available positions.

The project manager obtained the assistance of an executive sponsor who, working with human resources, created a new position within thirty days. Without executive sponsorship, the bureaucratic system creating a new position would have taken months. By that time, the project would have been over.

In a second case study, the president of a medium-sized manufacturing company, a subsidiary of a larger corporation, wanted to act as sponsor on a special project. The project manager decided to make full use of this high-ranking sponsor by assigning him certain critical functions. As part of the project's schedule, four months were allocated to obtain corporate approval for tooling dollars. The project manager “assigned” this task to the project sponsor, who reluctantly agreed to fly to corporate headquarters. He returned two days later with authorization for tooling. The company actually reduced project completion time by four months, thanks to the project sponsor.

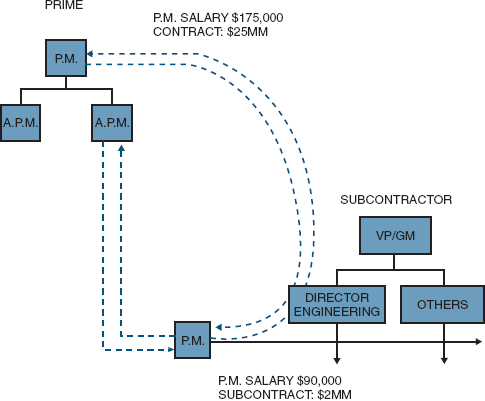

Figure 10-2 represents a situation where there were two project sponsors for one project. Alpha Company received a $25 million prime contractor project from the Air Force and subcontracted out $2 million to Beta Company. The project manager in Alpha Company earned $175,000 per year and refused to communicate directly with the project manager of Beta Company because his salary was only $90,000 per year. After all, as one executive said, “Elephants don't communicate with mice.” The Alpha Company project manager instead sought out someone at Beta in his own salary range to act as the project sponsor, and the burden fell on the director of engineering.

FIGURE 10-2. Multiple project sponsors.

The Alpha Company project manager reported to an Air Force colonel. The Air Force colonel considered his counterpart in Beta Company to be the vice president and general manager. Here, power and title were more important than the $100,000 differential in their salaries. Thus, there was one project sponsor for the prime contractor and a second project sponsor for the customer.

In some industries, such as construction, the project sponsor is identified in the proposal, and thus everyone knows who it is. Unfortunately, there are situations where the project sponsor is “hidden,” and the project manager may not realize who it is, or know if the customer realizes who it is. This concept of invisible sponsorship occurs most frequently at the executive level and is referred to as absentee sponsorship.

There are several ways that invisible sponsorship can occur. The first is when the manager who is appointed as a sponsor refuses to act as a sponsor for fear that poor decisions or an unsuccessful project could have a negative impact on his or her career. The second type results when an executive really does not understand either sponsorship or project management and simply provides lip service to the sponsorship function. The third way involves an executive who is already overburdened and simply does not have the time to perform meaningfully as a sponsor. The fourth way occurs when the project manager refuses to keep the sponsor informed and involved. The sponsor may believe that everything is flowing smoothly and that he is not needed.

Some people contend that the best way for the project manager to work with an invisible sponsor is for the project manager to make a decision and then send a memo to the sponsor stating “This is the decision that I have made and, unless I hear from you in the next 48 hours, I will assume that you agree with my decision.”

The opposite extreme is the sponsor who micromanages. One way for the project manager to handle this situation is to bury the sponsor with work in hopes that he will let go. Unfortunately this could end up reinforcing the sponsor's belief that what he is doing is correct.

The better alternative for handling a micromanaging sponsor is to ask for role clarification. The project manager should try working with the sponsor to define the roles of project manager and project sponsor more clearly.

The invisible sponsor and the overbearing sponsor are not as detrimental as the “can't-say-no” sponsor. In one company, the executive sponsor conducted executive-client communications on the golf course by playing golf with the customer's sponsor. After every golf game, the executive sponsor would return with customer requests, which were actually scope changes that were considered as no-cost changes by the customer. When a sponsor continuously says “yes” to the customer, everyone in the contractor's organization eventually suffers.

Sometimes the existence of a sponsor can do more harm than good, especially if the sponsor focuses on the wrong objectives around which to make decisions. The following two remarks were made by two project managers at an appliance manufacturer:

- Projects here emphasize time measures: deadlines! We should emphasize milestones reached and quality. We say, “We'll get you a system by a deadline.” We should be saying, “We'll get you a good system.”

- Upper management may not allow true project management to occur. Too many executives are “date-driven” rather than “requirements-driven.” Original target dates should be for broad planning only. Specific target dates should be set utilizing the full concept of project management (i.e., available resources, separation of basic requirements from enhancements, technical and hardware constraints, unplanned activities, contingencies, etc.)

These comments illustrate the necessity of having a sponsor who understands project management rather than one who simply assists in decision-making. The goals and objectives of the sponsor must be aligned with the goals and objectives of the project, and they must be realistic. If sponsorship is to exist at the executive levels, the sponsor must be visible and constantly informed concerning the project status.

Committe Sponsorship

For years companies have assigned a single individual as the sponsor for a project. The risk was that the sponsor would show favoritism to his line group and suboptimal decision-making would occur. Recently, companies have begun looking at sponsorship by committee to correct this.

Committee sponsorship is common in those organizations committed to concurrent engineering and shortening product development time. Committees are comprised of middle managers from marketing, R&D, and operations. The idea is that the committee will be able to make decisions in the best interest of the company more easily than a single individual could.

Committee sponsorship also has its limitations. At the executive levels, it is almost impossible to find time when senior managers can convene. For a company with a large number of projects, committee sponsorship may not be a viable approach.

In time of crisis, project managers may need immediate access to their sponsors. If the sponsor is a committee, then how does the project manager get the committee to convene quickly? Also, individual project sponsors may be more dedicated than committees. Committee sponsorship has been shown to work well if one, and only one, member of the committee acts as the prime sponsor for a given project.

When to Seek Help

During status reporting, a project manager can wave either a red, yellow, or green flag. This is known as the “traffic light” reporting system, thanks in part to color printers. For each element in the status report, the project manager will illuminate one of three lights according to the following criteria:

- Green light: Work is progressing as planned. Sponsor involvement is not necessary.

- Yellow light: A potential problem may exist. The sponsor is informed but no action by the sponsor is necessary at this time.

- Red light: A problem exists that may affect time, cost, scope, or quality. Sponsor involvement is necessary.

Yellow flags are warnings that should be resolved at the middle levels of management or lower.

If the project manager waves a red flag, then the sponsor will probably wish to be actively involved. Red flag problems can affect the time, cost, or performance constraints of the project and an immediate decision must be made. The main function of the sponsor is to assist in making the best possible decision in a timely fashion.

Both project sponsors and project managers should not encourage employees to come to them with problems unless the employees also bring alternatives and recommendations. Usually, employees will solve most of their own problems once they prepare alternatives and recommendations.

Good corporate cultures encourage people to bring problems to the surface quickly for resolution. The quicker the potential problem is identified, the more opportunities are available for resolution.

A current problem plaguing executives is who determines the color of the light. Consider the following problem: A department manager had planned to perform 1000 hours of work in a given time frame but has completed only 500 hours at the end of the period. According to the project manager's calculation, the project is behind schedule, and he would prefer to have the traffic light colored yellow or red. The line manager, however, feels that he still has enough “wiggle room” in his schedule and that his effort will still be completed within time and cost, so he wants the traffic light colored green. Most executives seem to favor the line manager who has the responsibility for the deliverable. Although the project manager has the final say on the color of traffic light, it is most often based upon the previous working relationship between the two and the level of trust.

Some companies use more than three colors to indicate project status. One company also has an orange light for activities that are still being performed after the target milestone date.

The New Role of the Executive

As project management matures, executives decentralize project sponsorship to middle- and lower-level management. Senior management then takes on new roles such as:

- Establishing a Center for Excellence in project management

- Establishing a project office or centralized project management function

- Creating a project management career path

- Creating a mentorship program for newly appointed project managers

- Creating an organization committed to benchmarking best practices in project management in other organizations

- Providing strategic information for risk management

This last bullet requires further comment. Because of the pressure placed upon the project manager for schedule compression, risk management could very well become the single most critical skill for project managers. Executives will find it necessary to provide project management with strategic business intelligence, assist in risk identification, and evaluate or prioritize risk-handling options.

Active versus Passive Involvement

One of the questions facing senior management in the assigning of a project sponsor is whether or not the sponsor should have a vested interest in the project or be an impartial outsider. Table 10-3 shows the pros and cons of this. Sponsors that that do not have a vested interest in the project seem to function more as exit champions rather than project sponsors.

Managing Scope Creep

Technically oriented team members are motivated not only by meeting specifications, but also by exceeding them. Unfortunately, exceeding specifications can be quite costly. Project managers must monitor scope creep and develop plans for controlling scope changes.

PMBOK® Guide, 4th Edition

5.5 Scope control

5.5.3.3 Change Control System

But what if it is the project manager who initiates scope creep? The project sponsor must meet periodically with the project manager to review the scope baseline changes or unauthorized changes may occur and significant cost increases will result, as shown in Situation 10-1 below:

TABLE 10-3. VESTED INTEREST OR NOT?

SITUATION 10–1: PINE LAKE AMUSEMENT PARK

After six years of debate, the board of directors of Pine Lake Amusement Park finally came to an agreement on the park's new aquarium. The aquarium would be built, at an estimated cost of $30 million and, between fundraising and bank loans, financing was possible.

After the drawings were completed and approved, the project was estimated as a two-year construction effort. Because of the project's complexity, a decision was made to have the project manager brought on board from the beginning of the design efforts, and to remain until six months after opening day. The project manager assigned was well known for his emphasis on details and his strong feelings for the aesthetic beauty of a ride or show.

The drawings were completed and a detailed construction cost estimate was undertaken. When the final cost estimate of $40 million was announced, the board of directors was faced with three alternatives: cancel the project, seek an additional $10 million in financing, or descope (i.e., reduce functionality of) the project. Additional funding was unacceptable and years of publicity on the future aquarium would be embarrassing for the board if the project were to be canceled. The only reasonable alternative was to reduce the project's scope.

After two months of intensive replanning, the project team proposed a $32 million aquarium. The board of directors agreed to the new design and the construction phase of the project began. The project manager was given specific instructions that cost overruns would not be tolerated.

At the end of the first year, more than $22 million had been spent. Not only had the project manager reinserted the scope that had been removed during the descoping efforts, but also additional scope creep had increased to the point where the final cost would now exceed $62 million. The new schedule now indicated a three-year effort. By the time that management held its review meetings with the project team, the changes had been made.

The Executive Champion

Executive champions are needed for those activities that require the implementation of change, such as a new corporate methodology for project management. Executive champions “drive” the implementation of project management down into the organization and accelerate its acceptance because their involvement implies executive-level support and interest.

10.2 HANDLING DISAGREEMENTS WITH THE SPONSOR

For years, we believed that the project sponsor had the final say on all decisions affecting the project. The sponsor usually had a vested interest in the project and was responsible for obtaining funding for the project. But what if the project manager believes that the sponsor has made the wrong decision? Should the project manager have a path for recourse action in such a situation?

There are several reasons why disagreements between the project manager and project sponsor will occur. First, the project sponsors may not have sufficient technical knowledge or information to evaluate the risks of any potential decision. Second, sponsors may be heavily burdened with other activities and unable to devote sufficient time to sponsorship. Third, some companies prefer to assign sponsors who have no vested interest in the project in hopes of getting impartial decision-making. Finally, sponsorship may be pushed down to a middle-management level where the assigned sponsor may not have all of the business knowledge necessary to make the best decisions.

Project managers are expected to challenge the project's assumptions continuously. This could lead to trade-offs. It could also lead to disagreements and conflicts between the project manager and the project sponsor. In such cases, the conflict will be brought to the executive steering committee for resolution. Sponsors must understand that their decisions as a sponsor can and should be challenged by the project manager.

Recognizing that these conflicts can exist, companies are instituting executive steering committees or executive policy board committees to quickly resolve these disputes. Few conflicts ever make it to the executive steering committee, but those that do are usually severe and may expose the company to unwanted risks.

A common conflict that may end up at the executive steering committee level is when one party wants to cancel the project and the second party wants to continue. This situation occurred at a telecommunications company where the project manager felt that the project should be canceled but the sponsor wanted the project to continue because its termination would reflect poorly upon him. Unfortunately, the steering committee sided with the sponsor and let the project continue. The company squandered precious resources for several more months before finally terminating the project.

10.3 THE COLLECTIVE BELIEF

Some projects, especially very long-term projects, often mandate that a collective belief exist. The collective belief is a fervent, and perhaps blind, desire to achieve that can permeate the entire team, the project sponsor, and even the most senior levels of management. The collective belief can make a rational organization act in an irrational manner. This is particularly true if the project sponsor spearheads the collective belief.

When a collective belief exists, people are selected based upon their support for the collective belief. Nonbelievers are pressured into supporting the collective belief and team members are not allowed to challenge the results. As the collective belief grows, both advocates and nonbelievers are trampled. The pressure of the collective belief can outweigh the reality of the results.

There are several characteristics of the collective belief, which is why some large, high-technology projects are often difficult to kill:

- Inability or refusal to recognize failure

- Refusing to see the warning signs

- Seeing only what you want to see

- Fearful of exposing mistakes

- Viewing bad news as a personal failure

- Viewing failure as a sign of weakness

- Viewing failure as damage to one's career

- Viewing failure as damage to one's reputation

10.4 THE EXIT CHAMPION

Project sponsors and project champions do everything possible to make their project successful. But what if the project champions, as well as the project team, have blind faith in the success of the project? What happens if the strongly held convictions and the collective belief disregard the early warning signs of imminent danger? What happens if the collective belief drowns out dissent?

In such cases, an exit champion must be assigned. The exit champion sometimes needs to have some direct involvement in the project in order to have credibility, but direct involvement is not always a necessity. Exit champions must be willing to put their reputation on the line and possibly face the likelihood of being cast out from the project team. According to Isabelle Royer1:

Sometimes it takes an individual, rather than growing evidence, to shake the collective belief of a project team. If the problem with unbridled enthusiasm starts as an unintended consequence of the legitimate work of a project champion, then what may be needed is a countervailing force—an exit champion. These people are more than devil's advocates. Instead of simply raising questions about a project, they seek objective evidence showing that problems in fact exist. This allows them to challenge—or, given the ambiguity of existing data, conceivably even to confirm—the viability of a project. They then take action based on the data.

The larger the project and the greater the financial risk to the firm, the higher up the exit champion should reside. If the project champion just happens to be the CEO, then someone on the board of directors or even the entire board of directors should assume the role of the exit champion. Unfortunately, there are situations where the collective belief permeates the entire board of directors. In this case, the collective belief can force the board of directors to shirk their responsibility for oversight.

Large projects incur large cost overruns and schedule slippages. Making the decision to cancel such a project, once it has started, is very difficult, according to David Davis2:

The difficulty of abandoning a project after several million dollars have been committed to it tends to prevent objective review and recosting. For this reason, ideally an independent management team—one not involved in the projects development—should do the recosting and, if possible, the entire review. ... If the numbers do not holdup in the review and recosting, the company should abandon the project. The number of bad projects that make it to the operational stage serves as proof that their supporters often balk at this decision.

. . . Senior managers need to create an environment that rewards honesty and courage and provides for more decision making on the part of project managers. Companies must have an atmosphere that encourages projects to succeed, but executives must allow them to fail.

The longer the project, the greater the necessity for the exit champions and project sponsors to make sure that the business plan has “exit ramps” such that the project can be terminated before massive resources are committed and consumed. Unfortunately, when a collective belief exists, exit ramps are purposefully omitted from the project and business plans. Another reason for having exit champions is so that the project closure process can occur as quickly as possible. As projects approach their completion, team members often have apprehension about their next assignment and try to stretch out the existing project until they are ready to leave. In this case, the role of the exit champion is to accelerate the closure process without impacting the integrity of the project.

Some organizations use members of a portfolio review board to function as exit champions. Portfolio review boards have the final say in project selection. They also have the final say as to whether or not a project should be terminated. Usually, one member of the board functions as the exit champion and makes the final presentation to the remainder of the board.

10.5 THE IN-HOUSE REPRESENTATIVES

On high-risk, high-priority projects or during periods of mistrust, customers may wish to place in-house representatives in the contractor's plant. These representatives, if treated properly, are like additional project office personnel who are not supported by your budget. They are invaluable resources for reading rough drafts of reports and making recommendations as to how their company may wish to see the report organized.

In-house representatives are normally not situated in or near the contractor's project office because of the project manager's need for some degree of privacy. The exception would be in the design phase of a construction project, where it is imperative to design what the customer wants and to obtain quick decisions and approvals.

Most in-house representatives know where their authority begins and ends. Some companies demand that in-house representatives have a project office escort when touring the plant, talking to functional employees, or simply observing the testing and manufacturing of components.

It is possible to have a disruptive in-house representative removed from the company. This usually requires strong support from the project sponsor in the contractor's shop. The important point here is that executives and project sponsors must maintain proper contact with and control over the in-house representatives, perhaps more so than the project manager.

10.6 STUDYING TIPS FOR THE PMI® PROJECT MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION EXAM

This section is applicable as a review of the principles to support the knowledge areas and domain groups in the PMBOK® Guide. This chapter addresses:

- Integration Management

- Scope Management

- Human Resources Management

- Initiation

- Planning

- Execution

- Monitoring

- Closure

Understanding the following principles is beneficial if the reader is using this text to study for the PMP® Certification Exam:

- Role of the executive sponsor or project sponsor

- That the project sponsor need not be at the executive levels

- That some projects have committee sponsorship

- When to bring a problem to the sponsor and what information to bring with you

In Appendix C, the following Dorale Products mini–case studies are applicable:

- Dorale Products (G) [Integration and Scope Management]

The following multiple-choice questions will be helpful in reviewing the principles of this chapter:

- The role of the project sponsor during project initiation is to assist in:

- Defining the project's objectives in both business and technical terms

- Developing the project plan

- Performing the project feasibility study

- Performing the project cost-benefit analysis

- The role of the project sponsor during project execution is to:

- Validate the project's objectives

- Validate the execution of the plan

- Make all project decisions

- Resolve problems/conflicts that cannot be resolved elsewhere in the organization

- The role of the project sponsor during the closure of the project or a life-cycle phase of the project is to:

- Validate that the profit margins are correct

- Sign off on the acceptance of the deliverables

- Administer performance reviews of the project team members

- All of the above

ANSWERS

- A

- D

- B

PROBLEMS

10–1 Should age have a bearing on how long it takes an executive to accept project management?

10–2 You have been called in by the executive management of a major utility company and asked to give a “selling” speech on why the company should go to project management. What are you going to say? What areas will you stress? What questions would you expect the executives to ask? What fears do you think the executives might have?

10–3 Some executives would prefer to have their project managers become tunnel-vision workaholics, with the project managers falling in love with their jobs and living to work instead of working to live. How do you feel about this?

10–4 Project management is designed to make effective and efficient use of resources. Most companies that adopt project management find it easier to underemploy and schedule overtime than to overemploy and either lay people off or drive up the overhead rate. A major electrical equipment manufacturer contends that with proper utilization of the project management concept, the majority of the employees who leave the company through either termination or retirement do not have to be replaced. Is this rationale reasonable?

10–5 The director of engineering services of R. P. Corporation believes that a project organizational structure of some sort would help resolve several of his problems. As part of the discussion, the director has made the following remarks: “All of our activities (or so-called projects if you wish) are loaded with up-front engineering. We have found in the past that time is the important parameter, not quality control or cost. Sometimes we rush into projects so fast that we have no choice but to cut corners, and, of course, quality must suffer.”

What questions, if any, would you like to ask before recommending a project organizational form? Which form will you recommend?

10–6 How should a project manager react when he finds inefficiency in the functional lines? Should executive management become involved?

10–7 An electrical equipment manufacturing company has just hired you to conduct a three-day seminar on project management for sixty employees. The president of the company asks you to have lunch with him on the first day of the seminar. During lunch, the executive remarks, “I inherited the matrix structure when I took over. Actually I don't think it can work here, and I'm not sure how long I'll support it.” How should you continue at this point?

10–8 Should project managers be permitted to establish prerequisites for top management regarding standard company procedures?

10–9 During the implementation of project management, you find that line managers are reluctant to release any information showing utilization of resources in their line function. How should this situation be handled, and by whom?

10–10 Corporate engineering of a large corporation usually assumes control of all plant expansion projects in each of its plants for all projects over $25 million. For each case below, discuss the ramifications of this, assuming that there are several other projects going on in each plant at the same time as the plant expansion project.

- The project manager is supplied by corporate engineering and reports to corporate engineering, but all other resources are supplied by the plant manager.

- The project manager is supplied by corporate but reports to the plant manager for the duration of the project.

- The plant manager supplies the project manager, and the project manager reports “solid” to corporate and “dotted” to the plant manager for the duration of the project.

10–11 An aircraft company requires seven years from initial idea to full production of a military aircraft. Consider the following facts: engineering design requires a minimum of two years of R&D; manufacturing has a passive role during this time; and engineering builds its own prototype during the third year.

- To whom in the organization should the program manager, project manager, and project engineering report? Does your answer depend on the life-cycle phase?

- Can the project engineers be “solid” to the project manager and still be authorized by the engineering vice president to provide technical direction?

- What should be the role of marketing?

- Should there be a project sponsor?

10–12 Does a project sponsor have the right to have an in-house representative removed from his company?

10–13 An executive once commented that his company was having trouble managing projects, not because of a lack of tools and techniques, but because they (employees) did not know how to manage what they had. How does this relate to project management?

10–14 Ajax National is the world's largest machine tool equipment manufacturer. Its success is based on the experience of its personnel. The majority of its department managers are forty-five to fifty-five-year-old, nondegreed people who have come up from the ranks. Ajax has just hired several engineers with bachelors' and masters' degrees to control the project management and project engineering functions. Can this pose a problem? Are advanced-degreed people required because of the rapid rate of change of technology?

10–15 When does project management turn into overmanagement?

10–16 Brainstorming at United Central Bank (Part I): As part of the 1989 strategic policy plan for United Central Bank, the president, Joseph P. Keith, decided to embark on weekly “brainstorming meetings” in hopes of developing creative ideas that could lead to solutions to the bank's problems. The bank's executive vice president would serve as permanent chairman of the brainstorming committee. Personnel representation would be randomly selected under the constraint that 10 percent must be from division managers, 30 percent from department managers, 30 percent from section-level supervisors, and the remaining 30 percent from clerical and nonexempt personnel. President Keith further decreed that the brainstorming committee would criticize all ideas and submit only those that successfully passed the criticism test to upper-level management for review.

After six months, with only two ideas submitted to upper-level management (both ideas were made by division managers), Joseph Keith formed an inquiry committee to investigate the reasons for the lack of interest by the brainstorming committee participants. Which of the following statements might be found in the inquiry committee report? (More than one answer is possible.)

- Because of superior–subordinate relationships (i.e., pecking order), creativity is inhibited.

- Criticism and ridicule have a tendency to inhibit spontaneity.

- Good managers can become very conservative and unwilling to stick their necks out.

- Pecking orders, unless adequately controlled, can inhibit teamwork and problem solving.

- All seemingly crazy or unconventional ideas were ridiculed and eventually discarded.

- Many lower-level people, who could have had good ideas to contribute, felt inferior.

- Meetings were dominated by upper-level management personnel.

- The meetings were held at inappropriate places and times.

- Many people were not given adequate notification of meeting time and subject matter.

10–17 Brainstorming at United Central Bank (Part II): After reading the inquiry committee report, President Keith decided to reassess his thinking about brainstorming by listing the advantages and disadvantages. What are the arguments for and against brainstorming? If you were Joseph Keith, would you vote for or against the continuation of the brainstorming sessions?

10–18 Brainstorming at United Central Bank (Part III): President Keith evaluated all of the data and decided to give the brainstorming committee one more chance. What changes can Joseph Keith implement in order to prevent the previous problems from recurring?

10–19 Explain the meaning of the following proverb: “The first 10 percent of the work is accomplished with 90 percent of the budget. The second 90 percent of the work is accomplished with the remaining 10 percent of the budget.”

10–20 You are a line manager, and two project managers (each reporting to a divisional vice president) enter your office soliciting resources. Each project manager claims that his project is top priority as assigned by his own vice president. How should you, as the line manager, handle this situation? What are the recommended solutions to keep this situation from recurring repeatedly?

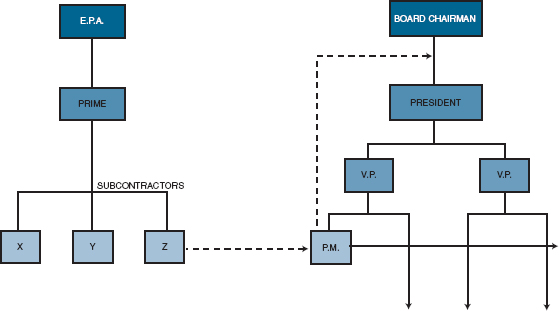

10–21 Figure 10-3 shows the organizational structure for a new Environmental Protection Agency project. Alpha Company was one of three subcontractors chosen for the contract. Because this was a new effort, the project manager reported “dotted” to the board chairman, who was acting as the project sponsor. The vice president was the immediate superior to the project manager.

Because the project manager did not believe that Alpha Company maintained the expertise to do the job, he hired an outside consultant from one of the local colleges. Both the EPA and the prime contractor approved of the consultant, and the consultant's input was excellent.

The project manager's superior, the vice president, disapproved of the consultant, continually arguing that the company had the expertise internally. How should you, the project manager, handle this situation?

10–22 You are the customer for a twelve-month project. You have team meetings scheduled with your subcontractor on a monthly basis. The contract has a contractual requirement to prepare a twenty-five- to thirty-page handout for each team meeting. Are there any benefits for you, the customer, to see these handouts at least three to four days prior to the team meeting?

FIGURE 10-3. Organizational chart for EPA project.

10–23 You have a work breakdown structure (WBS) that is detailed to level 5. One level-5 work package requires that a technical subcontractor be selected to support one of the technical line organizations. Who should be responsible for customer–contractor communications: the project office or line manager? Does your answer depend on the life-cycle phase? The level of the WBS? Project manager's “faith” in the line manager?

10–24 Should a client have the right to communicate directly to the project staff (i.e., project office) rather than directly to the project manager, or should this be at the discretion of the project manager?

10–25 Your company has assigned one of its vice presidents to function as your project sponsor. Unfortunately, your sponsor refuses to make any critical decisions, always “passing the buck” back to you. What should you do? What are your alternatives and the pros and cons of each? Why might an executive sponsor act in this manner?

CASE STUDY

CORWIN CORPORATION*

By June 2003, Corwin Corporation had grown into a $950 million per year corporation with an international reputation for manufacturing low-cost, high-quality rubber components. Corwin maintained more than a dozen different product lines, all of which were sold as off-the-shelf items in department stores, hardware stores, and automotive parts distributors. The name “Corwin” was now synonymous with “quality.” This provided management with the luxury of having products that maintained extremely long life cycles.

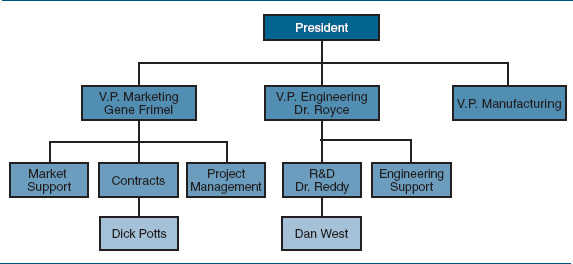

Exhibit 10-1. Organizational chart for Corwin Corporation

Organizationally, Corwin had maintained the same structure for more than fifteen years (see Exhibit 10-1). The top management of Corwin Corporation was highly conservative and believed in a marketing approach to find new markets for existing product lines rather than to explore for new products. Under this philosophy, Corwin maintained a small R&D group whose mission was simply to evaluate state-of-the-art technology and its application to existing product lines.

Corwin's reputation was so good that they continually received inquiries about the manufacturing of specialty products. Unfortunately, the conservative nature of Corwin's management created a “do not rock the boat” atmosphere opposed to taking any type of risks. A management policy was established to evaluate all specialty-product requests. The policy required answering the following questions:

- Will the specialty product provide the same profit margin (20 percent) as existing product lines?

- What is the total projected profitability to the company in terms of follow-on contracts?

- Can the specialty product be developed into a product line?

- Can the specialty product be produced with minimum disruption to existing product lines and manufacturing operations?

These stringent requirements forced Corwin to no-bid more than 90 percent of all specialty-product inquiries.

Corwin Corporation was a marketing-driven organization, although manufacturing often had different ideas. Almost all decisions were made by marketing with the exception of product pricing and estimating, which was a joint undertaking between manufacturing and marketing. Engineering was considered as merely a support group to marketing and manufacturing.

For specialty products, the project managers would always come out of marketing even during the R&D phase of development. The company's approach was that if the specialty product should mature into a full product line, then there should be a product line manager assigned right at the onset.

In 2000, Corwin accepted a specialty-product assignment from Peters Company because of the potential for follow-on work. In 2001 and 2002, and again in 2003, profitable follow-on contracts were received, and a good working relationship developed, despite Peter's reputation for being a difficult customer to work with.

On December 7, 2002, Gene Frimel, the vice president of marketing at Corwin, received a rather unusual phone call from Dr. Frank Delia, the marketing vice president at Peters Company.

Delia: “Gene, I have a rather strange problem on my hands. Our R&D group has $250,000 committed for research toward development of a new rubber product material, and we simply do not have the available personnel or talent to undertake the project. We have to go outside. We'd like your company to do the work. Our testing and R&D facilities are already overburdened.”

Frimel: “Well, as you know, Frank, we are not a research group even though we've done this once before for you. And furthermore, I would never be able to sell our management on such an undertaking. Let some other company do the R&D work and then we'll take over on the production end.”

Delia: “Let me explain our position on this. We've been burned several times in the past. Projects like this generate several patents, and the R&D company almost always requires that our contracts give them royalties or first refusal for manufacturing rights.”

Frimel: “I understand your problem, but it's not within our capabilities. This project, if undertaken, could disrupt parts of our organization. We're already operating lean in engineering.”

Delia: “Look, Gene! The bottom line is this: We have complete confidence in your manufacturing ability to such a point that we're willing to commit to a five-year production contract if the product can be developed. That makes it extremely profitable for you.”

Frimel: “You've just gotten me interested. What additional details can you give me?”

Delia: “All I can give you is a rough set of performance specifications that we'd like to meet. Obviously, some trade-offs are possible.”

Frimel: “When can you get the specification sheet to me?”

Delia: “You'll have it tomorrow morning. I'll ship it overnight express.”

Frimel: “Good! I'll have my people look at it, but we won't be able to get you an answer until after the first of the year. As you know, our plant is closed down for the last two weeks in December, and most of our people have already left for extended vacations.”

Delia: “That's not acceptable! My management wants a signed, sealed, and delivered contract by the end of this month. If this is not done, corporate will reduce our budget for 2003 by $250,000, thinking that we've bitten off more than we can chew. Actually, I need your answer within forty-eight hours so that I'll have some time to find another source.”

Frimel: “You know, Frank, today is December 7, Pearl Harbor Day. Why do I feel as though the sky is about to fall in?”

Delia: “Don't worry, Gene! I'm not going to drop any bombs on you. Just remember, all that we have available is $250,000, and the contract must be a firm-fixed-price effort. We anticipate a six-month project with $125,000 paid on contract signing and the balance at project termination.”

Frimel: “I still have that ominous feeling, but I'll talk to my people. You'll hear from us with a go or no-go decision within forty-eight hours. I'm scheduled to go on a cruise in the Caribbean, and my wife and I are leaving this evening. One of my people will get back to you on this matter.”

Gene Frimel had a problem. All bid and no-bid decisions were made by a four-man committee composed of the president and the three vice presidents. The president and the vice president for manufacturing were on vacation. Frimel met with Dr. Royce, the vice president of engineering, and explained the situation.

Royce: “You know, Gene, I totally support projects like this because it would help our technical people grow intellectually. Unfortunately, my vote never appears to carry any weight.”

Frimel: “The profitability potential as well as the development of good customer relations makes this attractive, but I'm not sure we want to accept such a risk. A failure could easily destroy our good working relationship with Peters Company.”

Royce: “I'd have to look at the specification sheets before assessing the risks, but I would like to give it a shot.”

Frimel: “I'll try to reach our president by phone.”

By late afternoon, Frimel was fortunate enough to be able to contact the president and received a reluctant authorization to proceed. The problem now was how to prepare a proposal within the next two or three days and be prepared to make an oral presentation to Peters Company.

Frimel: “The Boss gave his blessing, Royce, and the ball is in your hands. I'm leaving for vacation, and you'll have total responsibility for the proposal and presentation. Delia wants the presentation this weekend. You should have his specification sheets tomorrow morning.”

Royce: “Our R&D director, Dr. Reddy, left for vacation this morning. I wish he were here to help me price out the work and select the project manager. I assume that, in this case, the project manager will come out of engineering rather than marketing.”

Frimel: “Yes, I agree. Marketing should not have any role in this effort. It's your baby all the way. And as for the pricing effort, you know our bid will be for $250,000. Just work backwards to justify the numbers. I'll assign one of our contracting people to assist you in the pricing. I hope I can find someone who has experience in this type of effort. I'll call Delia and tell him we'll bid it with an unsolicited proposal.”

Royce selected Dan West, one of the R&D scientists, to act as the project leader. Royce had severe reservations about doing this without the R&D director, Dr. Reddy, being actively involved. With Reddy on vacation, Royce had to make an immediate decision.

On the following morning, the specification sheets arrived and Royce, West, and Dick Potts, a contracts man, began preparing the proposal. West prepared the direct labor man-hours, and Royce provided the costing data and pricing rates. Potts, being completely unfamiliar with this type of effort, simply acted as an observer and provided legal advice when necessary. Potts allowed Royce to make all decisions even though the contracts man was considered the official representative of the president.

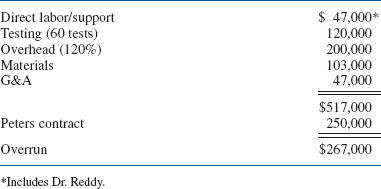

Finally completed two days later, the proposal was actually a ten-page letter that simply contained the cost summaries (see Exhibit 10-2) and the engineering intent. West estimated that thirty tests would be required. The test matrix described only the test conditions for the first five tests. The remaining twenty-five test conditions would be determined at a later date, jointly by Peters and Corwin personnel.

Exhibit 10-2. Proposal cost summaries

On Sunday morning, a meeting was held at Peters Company, and the proposal was accepted. Delia gave Royce a letter of intent authorizing Corwin Corporation to begin working on the project immediately. The final contract would not be available for signing until late January, and the letter of intent simply stated that Peters Company would assume all costs until such time that the contract was signed or the effort terminated.

West was truly excited about being selected as the project manager and being able to interface with the customer, a luxury that was usually given only to the marketing personnel. Although Corwin Corporation was closed for two weeks over Christmas, West still went into the office to prepare the project schedules and to identify the support he would need in the other areas, thinking that if he presented this information to management on the first day back to work, they would be convinced that he had everything under control.

The Work Begins. . .

On the first working day in January 2003, a meeting was held with the three vice presidents and Dr. Reddy to discuss the support needed for the project. (West was not in attendance at this meeting, although all participants had a copy of his memo.)

Reddy: “I think we're heading for trouble in accepting this project. I've worked with Peters Company previously on R&D efforts, and they're tough to get along with. West is a good man, but I would never have assigned him as the project leader. His expertise is in managing internal rather than external projects. But, no matter what happens, I'll support West the best I can.”

Royce: “You're too pessimistic. You have good people in your group and I'm sure you'll be able to give him the support he needs. I'll try to look in on the project every so often. West will still be reporting to you for this project. Try not to burden him too much with other work. This project is important to the company.”

West spent the first few days after vacation soliciting the support that he needed from the other line groups. Many of the other groups were upset that they had not been informed earlier and were unsure as to what support they could provide. West met with Reddy to discuss the final schedules.

Reddy: “Your schedules look pretty good, Dan. I think you have a good grasp on the problem. You won't need very much help from me. I have a lot of work to do on other activities, so I'm just going to be in the background on this project. Just drop me a note every once in a while telling me what's going on. I don't need anything formal. Just a paragraph or two will suffice.”

By the end of the third week, all of the raw materials had been purchased, and initial formulations and testing were ready to begin. In addition, the contract was ready for signature. The contract contained a clause specifying that Peters Company had the right to send an in-house representative into Corwin Corporation for the duration of the project. Peters Company informed Corwin that Patrick Ray would be the in-house representative, reporting to Delia, and would assume his responsibilities on or about February 15.

By the time Pat Ray appeared at Corwin Corporation, West had completed the first three tests. The results were not what was expected, but gave promise that Corwin was heading in the right direction. Pat Ray's interpretation of the tests was completely opposite to that of West. Ray thought that Corwin was “way off base,” and redirection was needed.

Ray: “Look, Dan! We have only six months to do this effort and we shouldn't waste our time on marginally acceptable data. These are the next five tests I'd like to see performed.”

West: “Let me look over your request and review it with my people. That will take a couple of days, and, in the meanwhile, I'm going to run the other two tests as planned.”

Ray's arrogant attitude bothered West. However, West decided that the project was too important to “knock heads” with Ray and simply decided to cater to Ray the best he could. This was not exactly the working relationship that West expected to have with the in-house representative.

West reviewed the test data and the new test matrix with engineering personnel, who felt that the test data were inconclusive as yet and preferred to withhold their opinion until the results of the fourth and fifth tests were made available. Although this displeased Ray, he agreed to wait a few more days if it meant getting Corwin Corporation on the right track.

The fourth and fifth tests appeared to be marginally acceptable just as the first three were. Corwin's engineering people analyzed the data and made their recommendations.

West: “Pat, my people feel that we're going in the right direction and that our path has greater promise than your test matrix.”

Ray: “As long as we're paying the bills, we're going to have a say in what tests are conducted. Your proposal stated that we would work together in developing the other test conditions. Let's go with my test matrix. I've already reported back to my boss that the first five tests were failures and that we're changing the direction of the project.”

West: “I've already purchased $30,000 worth of raw materials. Your matrix uses other materials and will require additional expenditures of $12,000.”

Ray: “That's your problem. Perhaps you shouldn't have purchased all of the raw materials until we agreed on the complete test matrix.”

During the month of February, West conducted fifteen tests, all under Ray's direction. The tests were scattered over such a wide range that no valid conclusions could be drawn. Ray continued sending reports back to Delia confirming that Corwin was not producing beneficial results and there was no indication that the situation would reverse itself. Delia ordered Ray to take any steps necessary to ensure a successful completion of the project.

Ray and West met again as they had done for each of the past forty-five days to discuss the status and direction of the project.

Ray: “Dan, my boss is putting tremendous pressure on me for results, and thus far I've given him nothing. I'm up for promotion in a couple of months and I can't let this project stand in my way. It's time to completely redirect the project.”

West: “Your redirection of the activities is playing havoc with my scheduling. I have people in other departments who just cannot commit to this continual rescheduling. They blame me for not communicating with them when, in fact, I'm embarrassed to.”

Ray: “Everybody has their problems. We'll get this problem solved. I spent this morning working with some of your lab people in designing the next fifteen tests. Here are the test conditions.”

West: “I certainly would have liked to be involved with this. After all, I thought I was the project manager. Shouldn't I have been at the meeting?”

Ray: “Look, Dan! I really like you, but I'm not sure that you can handle this project. We need some good results immediately, or my neck will be stuck out for the next four months. I don't want that. Just have your lab personnel start on these tests, and we'll get along fine. Also, I'm planning on spending a great deal of time in your lab area. I want to observe the testing personally and talk to your lab personnel.”

West: “We've already conducted twenty tests, and you're scheduling another fifteen tests. I priced out only thirty tests in the proposal. We're heading for a cost-overrun condition.”

Ray: “Our contract is a firm-fixed-price effort. Therefore, the cost overrun is your problem.”

West met with Dr. Reddy to discuss the new direction of the project and potential cost overruns. West brought along a memo projecting the costs through the end of the third month of the project (see Exhibit 10-3).

Dr. Reddy: “I'm already overburdened on other projects and won't be able to help you out. Royce picked you to be the project manager because he felt that you could do the job. Now, don't let him down. Send me a brief memo next month explaining the situation, and I'll see what I can do. Perhaps the situation will correct itself.”

Exhibit 10-3. Projected cost summary at the end of the third month

During the month of March, the third month of the project, West received almost daily phone calls from the people in the lab stating that Pat Ray was interfering with their job. In fact, one phone call stated that Ray had changed the test conditions from what was agreed on in the latest test matrix. When West confronted Ray on his meddling, Ray asserted that Corwin personnel were very unprofessional in their attitude and that he thought this was being carried down to the testing as well. Furthermore, Ray demanded that one of the functional employees be removed immediately from the project because of incompetence. West stated that he would talk to the employee's department manager. Ray, however, felt that this would be useless and said, “Remove him or else!” The functional employee was removed from the project.

By the end of the third month, most Corwin employees were becoming disenchanted with the project and were looking for other assignments. West attributed this to Ray's harassment of the employees. To aggravate the situation even further, Ray met with Royce and Reddy, and demanded that West be removed and a new project manager be assigned.

Royce refused to remove West as project manager, and ordered Reddy to take charge and help West get the project back on track.

Reddy: “You've kept me in the dark concerning this project, West. If you want me to help you, as Royce requested, I'll need all the information tomorrow, especially the cost data. I'll expect you in my office tomorrow morning at 8:00 A.M. I'll bail you out of this mess.”

West prepared the projected cost data for the remainder of the work and presented the results to Dr. Reddy (see Exhibit 10-4). Both West and Reddy agreed that the project was now out of control, and severe measures would be required to correct the situation, in addition to more than $250,000 in corporate funding.

Reddy: “Dan, I've called a meeting for 10:00 A.M. with several of our R&D people to completely construct a new test matrix. This is what we should have done right from the start.”

West: “Shouldn't we invite Ray to attend this meeting? I'm sure he'd want to be involved in designing the new test matrix.”

Reddy: “I'm running this show now, not Ray!! Tell Ray that I'm instituting new policies and procedures for in-house representatives. He's no longer authorized to visit the labs at his own discretion. He must be accompanied by either you or me. If he doesn't like these rules, he can get out. I'm not going to allow that guy to disrupt our organization. We're spending our money now, not his.”

Exhibit 10-4. Estimate of total project completion costs

West met with Ray and informed him of the new test matrix as well as the new policies and procedures for in-house representatives. Ray was furious over the new turn of events and stated that he was returning to Peters Company for a meeting with Delia.

On the following Monday, Frimel received a letter from Delia stating that Peters Company was officially canceling the contract. The reasons given by Delia were as follows:

- Corwin had produced absolutely no data that looked promising.

- Corwin continually changed the direction of the project and did not appear to have a systematic plan of attack.

- Corwin did not provide a project manager capable of handling such a project.

- Corwin did not provide sufficient support for the in-house representative.

- Corwin's top management did not appear to be sincerely interested in the project and did not provide sufficient executive-level support.

Royce and Frimel met to decide on a course of action in order to sustain good working relations with Peters Company. Frimel wrote a strong letter refuting all of the accusations in the Peters letter, but to no avail. Even the fact that Corwin was willing to spend $250,000 of their own funds had no bearing on Delia's decision. The damage was done. Frimel was now thoroughly convinced that a contract should not be accepted on “Pearl Harbor Day.”

*Case Study also appears at end of chapter.

1. Isabelle Royer, “Why Bad Projects are So Hard to Kill,” Harvard Business Review, February 2003, p. 11; Copyright © 2003 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. All rights reserved.

2. David Davis, “New Projects: Beware of False Economics,” Harvard Business Review, March–April 1985, pp. 100–101; Copyright © 1985 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

* Revised, 2007.