CHAPTER 7

LEADING A MULTICULTURAL VIRTUAL TEAM

As he sits on the bullet train, Jeremy Bouchard watches the skyline of Tokyo grow smaller by the minute. It is a familiar image now, as this is his fourth trip to Japan since taking on project manager duties for the Sitka project, a project that is entirely virtual and includes an automotive partner company located in Japan. As he sits on the train taking in the sights and sounds, he realized he can even understand some of the things being said around him. The Japanese language is becoming less foreign to him.

Being able to understand some of the Japanese language is one of many ways life has changed for Bouchard since becoming a virtual project manager. It is also the result of one of the biggest changes: He now spends much more time on business travel, connecting with members of his geographically distributed team. He realizes travel is necessary to establish social presence so he is more than a voice on a conference call or a name on an email message. His name now represents a person, a person who is the leader of his project team.

Another significant benefit that has come from his travels is that Bouchard has become much more culturally aware now that there is an international component to the project. He can attribute much of that cultural awareness to one of his core team members, Takashi Kido. Kido is a Japanese expatriate who is the subcontract manager of the Japanese supplier and serves as the liaison between the two companies. As Bouchard explains, he has learned a lot from Kido. “Takashi has stressed that trust is everything when doing business with the Japanese, and trust cannot happen until personal relationships are established. Much of my time in Japan is spent forging stronger relationships with our Japanese team members. Takashi has also explained that the organizational and management hierarchy is engrained in Japanese businesses and must be respected and used appropriately. But, the hardest cultural subtlety for me to remember is that in the Japanese business culture, ‘yes’ means ‘I understand you.’ It does not necessarily mean ‘I agree with you.’ I have had a couple instances where I assumed I had agreement on project responsibilities, only to find out later that I had assumed incorrectly.”

One of the biggest breakthroughs for Bouchard has been coming to the understanding that as the leader of a multicultural project team, it is his responsibility to converge his company's culture with the national cultures represented on the team. In doing so, he is creating the project culture that is based on his company culture, but is influenced and shaped by other national cultures. Much of that influence and shaping is establishing cultural awareness and respect across the project team. His travels to Japan have been as much about teaching his Japanese team members about his company and country culture as about learning Japanese culture.

Much like Bouchard's company, Sensor Dynamics, many businesses can no longer effectively compete within their industries and markets without direct involvement by individuals located around the globe. Traditional geographic boundaries can no longer remain barriers to work progress and therefore must be managed with innovative solutions for increasingly greater and smoother permeability of what were boundaries in the past.

One of the key challenges to increased globalization is consistent success in leading multicultural project teams and interacting and integrating with fellow employees, partners, and customers from other nations and cultures in virtual team environments. Although doing this is no doubt challenging, the potential for working together and melding into teams to accomplish shared missions and goals offers tremendous benefits to all who participate.

The value and benefit of cultural diversity is well understood by leading multinational companies within all industries, as they have learned to use cultural diversity as a competitive advantage. Among the greatest benefits stated are that cultural diversity:

- Uncovers new perspectives for looking at both opportunities and problems.

- Taps knowledge and experience that is different from the members of the home country.

- Generates innovation in ideas, suggestions, and methods for performing work.

Of course, these benefits can be realized to their full extent only if members of virtual project teams become more aware of and comfortable working in culturally diverse organizations. The intent of this chapter is to help virtual project managers be prepared to operate more effectively in a variety of multicultural environments.

Putting Culture in Context

When individuals from various countries participate on a project, the influence of culture is immediate. National culture influences project team members' ability to deal with ambiguous situations and ability to work and think independently and collectively, how they view personal accountability and personal contribution, and how comfortable they are directly interfacing with people at higher levels of the organization. But what is meant by culture?

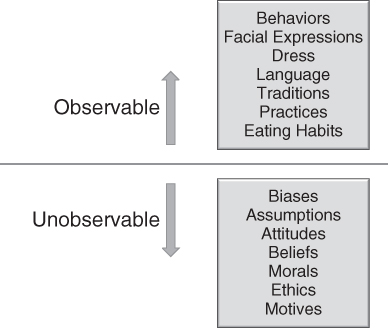

Culture is the total of all actions, mindsets, mentalities, and beliefs common to a group of individuals or a society. It is everything that people have, think, and do within that group or society. Culture can be exhibited in many ways, such as through spoken language, facial expressions, gestures, clothing, and rituals.1 As displayed in Figure 7.1, many of these exhibited traits, such as language, facial expressions, and dress, are observable. However, many aspects of culture, such as values and attitudes, are not observable and reside under the surface. Therefore, multinational team members must be much more cognizant, observant, and aware in order to perceive and understand the less observable cultural attributes.

Figure 7.1 Observable and Unobservable Cultural Attributes

Both national and company cultures directly exert tremendous influence on us as individuals. Generally, employees master what it takes to be successful in their existing company cultures over time. The challenge facing us in today's environment of growing globalization is the necessity to expand to become more multiculturally competent to understand, manage, and lead within organizations that are composed of more employees and team members from multiple nations. This is especially true when leading multinational virtual projects, where the collection of cultures becomes most evident and where cultural challenges first emerge. It is crucial that virtual project managers to become culturally aware and sensitive to members of their teams who represent multiple cultures and languages. Indeed, project managers in a virtual environment must pay attention to cultural differences and recognize their effect on team members' values, attitudes, and behaviors.

Cultural Intelligence

Achieving a level of cultural awareness in today's project teams means that project managers and team members understand the differences between themselves and team members from other countries and backgrounds. Cultural awareness is a subset of something much broader, called cultural intelligence. An individual who possesses cultural intelligence is skilled in and capable of understanding a culture, continuing to learn and be cognizant of ongoing cultural interactions, and has the ability to form thoughts and actions in ways that are more sensitive and sympathetic to those who represent other cultures.2 Researchers who specialize in studying cultural intelligence indicate that it is something that we all need, and its benefits are reflected in work performance. Specifically, their studies show that a culturally diverse work group that possesses cultural intelligence will outperform homogenous teams.3 Today it is a business necessity for virtual project managers to deal effectively with culturally diverse project teams. Project managers who do not improve their cultural intelligence skills put their virtual projects at risk.4 This added capability includes the ability to recognize the influence of their culture on how they behave as leaders of project teams as well as the influence their conduct has on the team's broader behavior. Cultural difference on a project team should be embraced, not ignored, and leveraged as a source of inspiration and discovery rather than of irritation and frustration.5 The team's diversity can be its strength.

Challenges of Multicultural Virtual Project Teams

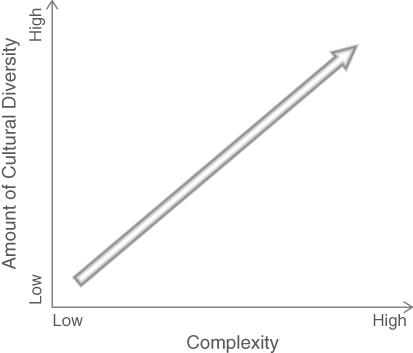

One of the effects of increased globalization is that people may become more entrenched in their own ways of thinking, which can lead to increased divergence between cultures.6 This behavior, of course, presents great challenges for virtual project managers. Cultural divisions will fracture the cohesiveness of the project network. As keystone members of the project network (see Chapter 6), virtual project managers must be the driving force of the convergence of cultural elements into an integrated project culture. Once again, we see the role of project managers as integrators emerge as a key responsibility. This responsibility adds yet another level of complexity to the virtual project, as illustrated in Figure 7.2.7

Figure 7.2 Complexity Grows as Cultural Diversity Increases

This complexity is magnified by the fact that culture is multilayered. Culture is like an underground river flowing through our lives—interactions and relationships providing clues; queues and messages that form our attitudes, perceptions, judgment; and ideas regarding ourselves, our team members, and others. What we see on the surface of our cultural perceptions may mask differences below the surface.8 Virtual project managers need to be culturally knowledgeable and sensitive in managing their project team by using flexibility, good communication, and mutual respect, and they must demonstrate the ability to compromise when needed.9

It is important to recognize that leaders of virtual project teams have in the past made mistakes, and will continue to do so as they dialogue and interact with teammates from other cultural backgrounds. This is true because, as individual team members, they are continuing to learn and practice cultural knowledge and awareness. No matter how hard team members try, they will never have complete knowledge of all of the cultures represented on virtual project teams.

Becoming aware of and sensitive to the cultural nuances that affect a multinational virtual project is necessary and foundational to effectively leading a culturally diverse project team. But, what virtual project managers ultimately have to do is create a project culture that converges both company and country cultures into a unique culture that defines how project team members will interact with one another and how the team will conduct its work. This is not an easy task, and it is yet another example of how managing a virtual project can be more complicated than managing a traditional project.

To create a project culture that takes into account cultural nuances, virtual project managers should become knowledgeable of the cultural factors that may affect their teams. That is, increase their cultural intelligence. The next section details the most prevalent cultural factors that will likely need to be taken into account when creating a multicultural project culture.

Cultural Factors

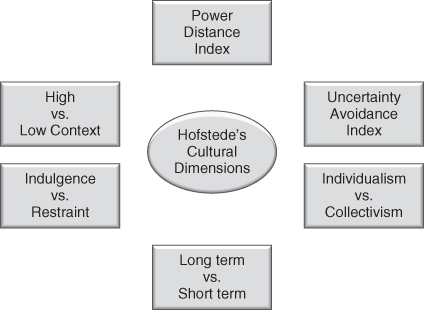

Several researchers have done a masterful job of identifying cultural factors that contribute to the cultural complexity associated with multicultural project teams. Their work is beneficial in helping project managers increase their understanding of how to recognize those cultural factors and use them to successfully manage multicultural teams. Foremost among these researchers is Geert Hofstede, whose cultural dimensions model (see Figure 7.3) includes the cultural factors of power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism versus collectivism, long-term versus short-term orientation, indulgence versus restraint, and high- versus low-context cultures.10

Figure 7.3 Hofstede's Cultural Dimensions Model

Power Distance Index

The power distance index refers to how power is distributed within an organization and the extent to which the less powerful and influential individuals within an organization accept that power is distributed unequally. For example, in low-power-distance cultures, people relate to one another more as equals regardless of formal position within an organization. Subordinates may expect to be consulted by management and expect the organization to be more participative in general. Title and status tend to be less critical in lower-power-distance countries. In high-power-distance cultures, in contrast, people accept power relationships that are more hierarchical and autocratic. Subordinates expect to be told what to do, and decisions made by individuals in higher positions are rarely questioned and critiqued. Power distance tends to be higher in Eastern Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin countries and lower in English-speaking and Western countries.11

Relative to virtual project teams, the power distance cultural factor could impact team members' perspectives on and understanding of the virtual project manager's management style and the communication dynamics within the company and on the project team. It therefore is important that, during discussions with the team regarding roles and responsibilities, project managers clearly specify exactly what will be the role of the team leader and what team members should expect from the leader. Project managers also should keep in mind that team members from low-power-distance cultures may want more involvement and consultation regarding potential changes and decisions on the project. In contrast, team members from high-power-distance cultures will wait to be tasked. Virtual project managers can use this knowledge to drive an appropriate level of collaboration and participation within the team. Knowledgeable virtual project managers are also more perceptive in sensing power distance discomfort and frustration within the team and respond accordingly. (See the box titled “Differing Power Distance Orientations.”)

Differing Power Distance Orientations

| High Power Distance (Hierarchical Orientation) | Low Power Distance (Participative Orientation) |

| Use senior management to make announcements and communicate changes. | Include team members in discussions and explain reasoning for directions and decisions. |

| Use formal management power to exercise authority. | Enable team members to ask questions and to challenge as appropriate. |

| Inform team members what to do instead of leaving them to figure it out on their own. | Provide a forum for team member discussions on project-related topics.12 |

Uncertainty Avoidance Index

The uncertainty avoidance index reflects a culture's tolerance for ambiguity, and it is a good indicator of whether individuals feel comfortable in unstructured situations. Team members from high-uncertainty-avoidance cultures are less likely to be comfortable in roles that are poorly defined or have ambiguous goals. In general, people from such cultures judge what is different as dangerous and risky. Team members from high-uncertainty-avoidance cultures may also seek more detail on project plans and expected outcomes and may prefer more predictable routines. High-uncertainty-avoidance cultures can be found in Greece, Yugoslavia, Japan, Belgium, France, South Korea, Italy, and many Latin American countries.

By contrast, team members from low-uncertainty-avoidance cultures are more comfortable in ambiguous situations and are more willing to take higher levels of risk to achieve an outcome. In general, team members from such cultures view new things with curiosity and seek opinions that may be in conflict with their own. Low-uncertainty-cultures can be found in North America, Great Britain, Hong Kong, Singapore, Sweden, Norway, Malaysia, and India.13

Virtual project managers have to be careful to match team assignments to individuals possessing the appropriate level of uncertainty avoidance. Additionally, project managers should ensure that team members from high-uncertainty-avoidance cultures have access to project requirements, plans, and schedules and have clear expectations on their roles and responsibilities.14 Change must be tolerated, but carefully managed to allow necessary change to happen and to assure team members that the change is not occurring in an ad hoc manner. (See the box titled “Dealing with Certainty and Uncertainty.”)

Dealing with Certainty and Uncertainty

| Need for Certainty | Tolerance for Uncertainty |

| Provide team members with specific tasks, expected outcomes, and goals. | Reward team members' creative behavior and willingness to take risks. |

| Recognize team members' need for project information. | Focus on the process of team learning. |

| Focus on compliance with project processes and procedures. | Relate issues and inquiries to the project mission and goals. |

| Use formal communication channels. | Enable team members to challenge and question the way things are done.15 |

Individualism versus Collectivism

Individualism versus collectivism addresses the degree to which people prefer to act as individuals rather than as members of a collective group. It also generally represents the degree to which individuals in a society want to become integrated into groups and other relationships. Individualism is more prevalent in North America, Great Britain, Australia, Italy, France, and Germany. People from high-individualism cultures are comfortable working independently, generally maintain looser ties to groups, and value individual recognition as much as team or group recognition.

People from high-collectivism cultures tend to be integrated into groups and value a strong identity with the group. They put the needs of the group before their own and stress the need for belonging and the maintenance of group harmony. Collectivism is strong in Central and South American countries and most Asian countries.16

Relative to virtual projects, team members from collective cultures tend to expect more interaction and involvement in relationships than team members from cultures strong in individualism. Virtual project managers should keep in mind that team members from collective cultures generally are not comfortable being singled out for recognition. Whenever possible, project managers should attempt to get to know the team members personally and try to build relationships beyond the work environment. Obviously doing this will require some travel on the part of virtual project managers. Highly individualistic members of a project team need to remain aware that they are members of a broader team and cannot perform all work independently. Virtual project managers need to be cognizant of the fact that team members' expectations about team unity, differences in personal bonding, and potentially the ways rewards and recognition are provided may be critical to the team's cohesiveness and should be subtly assessed as to what approaches work best in these situations. (See the box titled “Interacting with Individualistic and Collectivistic Team Members.”)17

Interacting with Individualistic and Collectivistic Team Members

| Individualistic Orientation | Collectivistic Orientation |

| Encourage team members to ask questions and seek information. | Focus on how change is good for the team as a whole. |

| Appeal to their observed self-interest when assigning tasks. | Appeal to their desire to work in groups when assigning tasks. |

| Provide individual awards when warranted. | Allow the small groups to spend time working out issues. |

| Provide team or small-group awards when warranted.18 |

Long-Term versus Short-Term Orientation

Long-versus short-term orientation describes a society's time horizon and the level of importance that is placed on past, present, and future events. It also reflects whether members of a culture prefer immediate fulfillment of their material, social, and emotional needs or if delays in this fulfillment are acceptable. In cultures with long-term orientations, values include perseverance, thrift, ordering relationships by status, and reflecting a sense of humility. Cultures with short-term orientations tend to be adaptable to changing circumstances and also emphasize quick results, personal stability, and sacrosanct traditions. In business, cultures that are short-term oriented value bottom-line results, and managers are consistently evaluated on their ability to deliver the results. East Asian countries scored the highest in long-term cultural orientation, while the United States, Australia, Latin America, Africa, and Muslim countries tend to have short-term orientations.19

On a multicultural project team, individuals from cultures with short-term orientations will most likely need less encouragement in holding to schedules as they tend to receive satisfaction from quick accomplishment and results on their tasks and assignments. In contrast, project managers can expect team members from cultures with long-term orientations to be more flexible and adaptable to project changes and adjustments. Project managers should ensure that team members from these cultures are encouraged to participate in project discussions relating to longer-term objectives and expectations.

High-Context versus Low-Context Cultures

Two key authors, Geert Hofstede and Edward Hall, independently developed paradigms for identifying cultural aspects which included high-context versus low-context cultures. The anthropologist Edward T. Hall in his book Beyond Culture, wrote about high-context and low-context cultures in regard to communication. Context, as used here, refers to how individuals in various cultures prefer to share information with others. It can relate to elements surrounding the communication process, such as tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language.20

Individuals from high-context cultures normally have extensive information networks and need a minimum amount of background perspective and data to go about their work. Generally, agreements are reinforced through their personal relationships.21 Individuals from high-context societies generally prefer more specific information than individuals from lower-context cultures, and they tend to focus on building harmony and relationships with others. They generally speak in an indirect manner, avoiding speaking negatively of others as much as possible. Higher-context individuals tend to thrive in professions such as marketing and human resources.

Individuals from lower-context cultures tend to be more task oriented. Such individuals might prefer working in professions such as engineering and finance. Typical examples of low-context societies are the United States, Canada, Israel, and the majority of northern European countries. Chinese, Japanese, African, and Arabic societies are examples of high-context cultures.22

Team members from high-context cultures might not understand communications such as emails and other forms of messaging well without more information provided on the topic or context. Members from lower-context cultures focus more on objective and factual information and require less background information. Virtual project managers should keep in mind that team members from low-context cultures may prefer more asynchronous communications whereas high-context personnel will seek out information-rich communication and collaboration channels such as video conferencing.

Interactions among low-context and high-context individuals may be somewhat challenging in virtual project teams. Therefore, the project managers need to remain cognizant of these potentially conflicting situations. As an example, high-context individuals may need more data and information pertaining to the project and specifically to their own assignment and responsibilities. Team members from low-context cultures may perceive being asked to provide data or information as insulting, as evidence that other team members do not trust them, or that others “just don't get it.” This fact leaves significant opportunity for verbal and written communications to be misinterpreted.23

Hans-Juergen Junkersdorf, senior business development manager for Motorola, had this to say about leading a multinational project team consisting of individuals from both low- and high-context cultures: “When leading a cross-cultural virtual team, you must know and understand the basics and the differences of the various cultures you will be working with on your team. The key is being able to adjust your leadership to fit the needs of both the high and the low context team members.” He added, “Team members from both extremes can exhibit hidden agendas which could impact your project. Hence, the project manager needs to listen carefully and make an effort to read the ‘white spaces’ between their comments and actions and combine that with the facts to gauge how best to adjust your leadership approach and how to manage the flow of project information and communication.”

This is very good advice from someone who has spent a number of years leading virtual project teams made up of members from multiple cultures.

Indulgence versus Restraint

Always looking to improve his model, in 2010 Hofstede added a sixth dimension described as indulgence versus restraint. Indulgence reflects a society that values relatively free and open gratification of basic and human impulses and desires. It pertains to enjoying life and having fun. Restraint, in contrast, relates to a society that values limitations and control of gratification of needs and attempts to regulate it through strict social norms. For example, such things as freedom of speech and the desire for significant leisure time are considered very important to individuals from societies that are high on the indulgence dimension. According to Hofstede, indulgence societies include North and South America, Western Europe, and parts of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Examples representing norms that are high on the restraint scale include stricter sexual norms, a perception of limited ability to affect the actions of a higher power, and lower emphasis on leisure time. Restraint is more prevalent in Eastern Europe and Asia and in the Muslim world. Mediterranean Europe tends to be middle of the road on this dimension.24

For project teams working in a multinational environment, this dimension may have influence on how willing team members are to express their opinions and provide feedback, especially if some team members are from a culture higher on the restraint scale. It also may have a bearing on turnover of team members and employees if they place considerable value on personal happiness, freedom, and leisure time. They may become uncomfortable in their current role and choose to explore new opportunities.

The cultural dimensions discussed above have predominantly been associated with the research work of Geert Hofstede. There are other cultural dimensions that have been identified that have a significant bearing on multinational virtual project teams that include convergent/divergent tendencies, assertiveness and language proficiency.

Convergent/Divergent Tendencies

Another cultural factor that may come into play on a multinational virtual project is known as convergent/divergent tendencies. Individuals from convergent societies have a preference for working on well-defined tasks and problems. They like to gain knowledge through learning while doing. They lean more toward being pragmatists who are more concerned with what works than with what appears to be true.

In contrast, people from divergent societies tend to prefer to work on vague and less defined challenges where many alternatives exist for a solution. Individuals from these cultures use more creative and holistic approaches to perform their work and concentrate on observation as a means of learning. Based on the ability to conceptualize, many researchers and authors associate Americans as convergent thinkers, whereas they see Europeans as more divergent thinkers focusing on larger concepts, such as from what philosophical position is the proposition derived.

It is highly unlikely that either convergent or divergent thinking alone can be used to lead virtual projects or solve problems related to them. For example, during the initiation phase of a virtual project, the team needs divergent thinking to analyze and create viable possibilities and solutions. During the planning and execution phases, the team needs convergent thinkers to pragmatically select the best project options and rally team members toward execution and implementation.25

Assertiveness

Assertiveness is a rather tricky cultural factor to manage on virtual projects. Assertive behavior is generally associated with goal-oriented individuals. Studies have revealed that males tend to be more assertive than females. However, a more persuasive cultural consideration may relate to our earlier discussion regarding individualist versus group orientation. Research indicates that participants from individualist cultures are more assertive than those from group oriented societies. One explanation given for this observation is that certain levels of assertiveness may not be tolerated in some collective societies. Variations have been observed in the degree of assertiveness in specific cultures, but it may not be appropriate to assume that East Asians, for example, are less assertive than North Americans. It is possible and likely that people from East Asian and other similar cultures may exhibit assertiveness in certain situations, but not in others. Studies have also found that individual attitudes versus social norms may be a key contributing element that distinguishes assertive cultural behavior from nonassertive behavior.26

When leading virtual project teams, team member assertiveness may be perceived as an asset or liability. Different cultures vary in their perceptions of some cultural factors, and assertiveness is one of the most divisive. Virtual project managers must remain cognizant that an individualistic approach of being brutally honest with a team member versus the collectivistic approach of face-saving may resonate well with individuals from some cultures, but be offensive to others. Therefore, project managers must be able to manage assertive team members who may reduce involvement and participation of team members from cultures who react negatively to assertive behavior.27

Paola Genovese, Marketing Director and experienced virtual program manager with Cinetix, views her assertiveness as a major asset. “Assertiveness is a key capability of a virtual project manager. Project managers are usually managing resources which are not under his or her direct control, meaning that the project manager is not the direct manager of team members. For this reason assertiveness, and in particular the capability to use assertive communication, is critical to managing the team. Leveraging good assertive communication, the virtual project manager can improve his or her leadership of the team. This is accomplished through providing balance and effectiveness and consistently working in the same direction as a team, no matter how distributed the team is, in order to successfully achieve the project goals.”

Language Proficiency

It has been stated that English (or, broken English) is the language of business. However, the English language is one of the most challenging languages to translate into native languages and vice versa. Many English words have multiple meanings, and a common expression in English may have a different meaning in other languages. Most members of multinational virtual projects are assigned to the projects because of their innate technical skills, rather than their language skills. In such cases, much can get lost in the communication process through improper translation. As illustrated in the Telephone Game in Chapter 1, disconnects in communication transfer regularly occur even among people who are co-located, from the same country, and speaking the same language. These language disconnects are magnified with virtual teams from multiple countries speaking multiple languages. These disconnects can create a loss of information and misinterpretation of critical project information during meetings and other forms of communication. And, of course, more is lost due to the lack of visual cues available during face-to-face communication, which is normally limited or not available to virtual teams, as discussed in Chapter 6.

It should be recognized, and team members should be sensitive to the fact, that people working in their non-native language can be at distinct disadvantages. It may take longer for them to communicate to adequately ensure that they are getting their messages across and that they fully understand what is being said to them and around them in the project team environment.28 Ideas that come from non-native speaking team members often are interpreted as more simplistic. Without adequate sensitivity, these team members are often afforded less respect and credit for their contributions.

Table 7.1 Western versus Non-Western Cultural Factor Categorization

| Western Cultural Values | Non-Western Cultural Values |

| Low power distance | High power distance |

| Low uncertainty avoidance | High uncertainty avoidance |

| Individualism | Collectivism |

| Short-term orientation | Long-term orientation |

| Indulgent tendency | Restraint tendency |

| Low context | High context |

| Personal achievement | Collective achievement |

| Equality | Hierarchy |

| Self-interest | Saving face |

| Respect for results | Respect for status |

| Personal rights | Social responsibility |

| Assertive and direct | Humility and passive |

| Self-assuredness | Self-abnegation |

| Vitality of youth cherished | Wisdom of years cherished |

| Materialistic | Spiritualistic |

| Seek change | Accept what is |

| Freedom of speech | Freedom of silence |

| Wealth viewed as result of enterprise | Wealth viewed as result of future |

| Outer-world dependent | Inner-world dependent |

There is no doubt that language proficiency is a valued and important skill for virtual project managers and members of internationally distributed teams. The need for language proficiency will continue to grow over time as more project work is distributed across the globe. Even today, many teams may conduct the majority of team meetings in English, but in practical terms, many other languages are used in communications specific to particular regions represented on the project. As this situation continues to increase, more and more project teams are realizing the need to audio record all meetings so that participants can listen to the parts of the meeting again as necessary. Companies are also recognizing the need to invest in language training for virtual team members, especially in the predominant language of virtual projects.

Evaluating Western versus Non-Western Culture

We wrap up our discussion on cultural factors by categorizing cultural factors in a manner often described as Western versus non-Western countries. Table 7.1 displays various cultural factors associated with this type of categorization. The side-by-side comparison is meant to provide a snapshot comparison of Non-Western cultures to those in the West. It is important to remember that these comparisons are generalized and may be good for a quick, initial assessment, but a more thorough analysis should be conducted to get a clear sense of similarities and differences in the cultural values represented by virtual project team members and stakeholders. This table provides a broader perspective based upon global regions on groupings of cultural observations that virtual project team members may come in contact with during their project assignments.

Creating a Cultural Strategy

Gaining an awareness of the cultural factors that are present on a multinational project is good practice that creates cultural intelligence for virtual project managers. But, that knowledge is of little value unless it is put to use toward leading the project team more effectively. The best project managers go beyond gaining an awareness of the cultural dichotomies on a team. They use the information and knowledge gained to reconcile those cultural dichotomies through modifications to how they lead team members and how they manage team communication, collaboration, andv decision making. To do this, project managers must develop a cultural strategy that reflects the cultural nuances and dichotomies on their team and which assists them in determining how best to modify their leadership and management approach in a multicultural project environment.

Cultural Self-Awareness

The first critical step in developing a cultural strategy is to become grounded in the cultural factors that will likely be present on a project based on the countries that are represented. This is where the cultural factors information detailed in Table 7.1 comes into play.

Normally, firms that perform project work internationally do so on a regular basis and have well-established sites and partners in various countries and regions. The national cultures represented on the company's projects are therefore mostly known prior to beginning the projects. Savvy virtual project managers will prepare in advance of a project assignment by studying the unique cultural factors that they will encounter on the team based on the countries in which their company operates. The project managers will then further refine this knowledge and understanding once their specific project team members are assigned. If possible, they may also take advantage of cultural awareness training and publications to learn more about specific cultures.

Since people are a product of their own culture, including project managers of multinational projects, we need to increase our self-awareness of cross-cultural values and behaviors in order to better understand one another. Project managers must be the champion for cross-cultural leadership and model good culturally sensitive behavior while leading project teams. (See the box titled “Seven Cultural Behaviors to Model.”)

Once project managers are assigned to a virtual project, they will gain specific information on who will be involved on the project and where they reside. This information allows project managers to move to the next step in building a cultural strategy: assessing the specific cross-cultural factors that are present on the project.

Assessing the Project Team Culture

Performing a cultural assessment based on national traits may seem too general and a bit stereotypical to some, but the intent is to make the major cultural dichotomies present on a multinational team visible and clear. Within any national culture, individuals vary. Therefore, we recommend performing the assessment on a national basis.

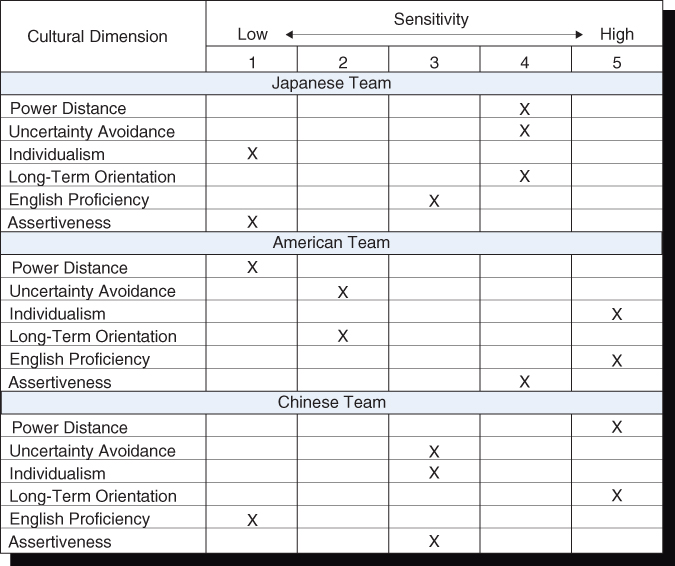

Figure 7.4 Cultural Assessment Example

The cultural assessment is a useful tool for virtual project managers to evaluate the varying cultural dimensions present on their teams.30 Cultural assessments are valuable in evaluating how a new multinational project stands with respect to cultural factors. But they can become quite complex and require an inordinate amount of time to generate. We advocate a simple approach that may be less precise than other approaches, but provides all the information necessary to develop a cultural strategy for the project. Figure 7.4 is an example of a simple cultural assessment tool that can be implemented easily.

The structure of the cultural assessment tool must be customized for the organization in which it is used and possibly for specific projects. The two primary structural components that need customization are the specific national cultures that will be evaluated and the cultural dimensions chosen as most important to evaluate. The teams represented should be straightforward based on the geographic locations of a multinational company. However, at times team composition may have to be modified. A good example of this comes from our friend Jeremy Bouchard, who has to include a Japanese automotive partner that is specific to the project he is managing and therefore must include the Japanese culture in his assessment.

Defining the appropriate cultural dimensions requires careful thought. This is where project managers' cultural self-awareness comes into focus. The overall intent of the cultural assessment is to identify any cultural extremes that may affect project management and collaboration among project members. Therefore, it is important to select cultural dimensions that will make the cultural extremes among the participating countries visible. For example, in the assessment example shown in Figure 7.4, one North American and two Asian countries are represented. Project managers with some cultural awareness knowledge will understand that there is likely to be some variation in cultural factors. We recommend using no more than six or seven dimensions when structuring a cultural assessment.

Once they construct the tool, virtual project managers can use it to assess the sensitivity to each of the cultural factors that affect their teams. To emphasize a point made previously, the sensitivities will vary from person to person on the team, so it is best to evaluate the team from a national perspective, not an individual perspective. For the example shown, the project manager has made an assessment that the team members from Japan will be relatively low on the individualism cultural factor. The manager must then determine just how low on the sensitivity scale the Japanese team members are relative to the rest of the team. There is no quantitative approach to this. Qualitative assessment skills must be used to make these determinations. A relatively accurate assessment of a team's cultural sensitivity can best be gained by personal and direct interaction with specific team members, just as Jeremy Bouchard did by traveling to meet his new Japanese team members.

The key to using the cultural assessment effectively is to identify the cultural factor extremes (either very low sensitivity or very high sensitivity). After identifying the extremes, project managers can develop a cultural strategy and use it to make adjustments to the way they manage the project and lead the team. These strategies can also be used to train and develop project team members and help navigate team members from forming to high performing.

Cultural Strategy

With the information contained in the cultural assessment, project managers can determine if there are any cultural circumstances unique to the project that have to be addressed. As an example, Figure 7.4 shows that there are significant cultural differences in the areas of power distance, assertiveness, language proficiency, and individualism that need to be addressed. Project managers must develop a cultural strategy that addresses how the differences in the cultural factors will be dealt with effectively. Every multinational project team is unique, so every cultural strategy will be unique. However, for the example shown, four cultural strategies could be developed.

Strategy 1: Power Distance

Since it was determined that both the Chinese and Japanese team members are from high-power-distance cultures, they may be sensitive to interacting with senior leaders within the company. The project manager should therefore be careful not to have these team members directly interface with or present to the senior organization leaders, at least not initially. The project manager should also ensure that clear roles and responsibilities are documented as well as all decision makers on the project.

Strategy 2: Assertiveness

The cultural assessment also showed a wide dichotomy with respect to assertiveness. This may be a source of contention even in team meetings; some participants may feel that a meeting contains lively debate while others might feel attacked or unnecessarily challenged. The project manager must monitor and facilitate the tone of cross-team communications, both verbal and written, until the variation in assertiveness begins to diminish and the team achieves a “performing” level of development. This behavior is also a team norm that should be addressed, documented, and discussed as part of the team charter. The project culture may require open and direct debate; therefore, expectations and understanding have to be established across the cultures represented on the project team.

Strategy 3: Language Proficiency

Proficiency in the primary language of the project (English, in this case) was identified as a cultural factor with high sensitivity. The team members from Shanghai especially had a low proficiency for communicating in spoken English. Due to this cultural factor, the project manager cannot rely heavily on verbal communication, but rather must establish a practice of repeating, in written form, any verbal instructions, critical discussions, and decisions. This will help to ensure that the team members in Shanghai understand and are fully engaged in the dialogue and work of the project team.

Strategy 4: Individualism versus Collectivism

Cultural preference for individualism ranges from high, to low, to moderate among the three nations represented on the example project. This distribution of preference is likely one of the most difficult factors to alleviate because it affects two major elements of any project: the tasking of work and rewards and recognition. Team members high on individualism can be tasked and rewarded individually. However, team members low on individualism and therefore high on collectivism should be given tasks that can be performed in small work groups. Rewards for these team members must be given as team awards. The virtual project manager must work hard to avoid demotivation and conflict.

With the cultural strategies established, project managers must use the strategies to modify how they will lead the people on the team and how they will manage project processes. Managers will, in effect, be using the cultural strategies to create an element of the project culture.

Converging Company and Country Culture

As an enterprise expands its business globally, it establishes operational components in a number of geographical regions and countries. The people acquired through mergers and acquisitions in each country come to the company with their own unique values, preferred behaviors, and languages that embody the culture of their society. Additionally, company acquisitions and strategic partnerships will bring new company cultures as well as national cultures into the enterprise. Managing across cultures with virtual projects requires integrating many different functional disciplines and support group personnel who all possess obvious and non-obvious differences in backgrounds and languages. Doing this requires the ability to integrate national, company, and project culture in a way that promotes collaboration and collective thinking. According to Margaret Lee, author of Leading Virtual Project Teams, “Successful integration of national cultures into one strong organizational culture can be an advantage in the competitive global marketplace. Ample evidence supports the fact that integrating organizational and national cultures is necessary for organizational effectiveness in the 21st century.”31 How are the many cultural differences reconciled to the point where a company remains operationally effective and maintains its original culture?

Authors and researchers continue to debate whether company or country culture has a stronger influence on team members. The truth of the matter is that it most likely depends on a host of many varied yet interrelated factors. Companies should comprehensively assess their organizational culture against the various local cultures, countries, and regions where they do business. It is not unusual for potential conflicts between organizational and national cultures to surface. Companies should be cognizant of these situations and plan to take the appropriate actions to ensure that employees from other countries remain motivated and committed to the organizational mission and objectives.32

Some people talk about the need to blend the cultures into a new culture that encompasses elements of each country's culture. In practice, doing so is a nearly impossible task, and as Mary Dunkin, a global project manager for Intel Corporation, explains, in cases where a company's culture is one of its competitive strengths, creating a blended culture can be counterproductive.33

In the early 2000s, Intel decided to enter the communication industry to augment its computing business, and did so through a significant number of company acquisitions. Over an 18-month period, we acquired over 20 companies. Over half of them were outside of our home country. In nearly every acquisition, the approach was to allow the company to remain autonomous in its operation and culture. Looking back, this was a poor approach and found to be the root cause of Intel failing to retain the value that they originally saw in these companies. By allowing the companies to operate autonomously operationally and culturally, we were not able to leverage Intel's vast assets and strong company culture that are both competitive advantages.

Dunkin then went on to explain, “we then tried a blended approach, particularly in regard to cross-country culture. A lot of time, effort, and money was expended on cultural sensitivity training and coaching. The goal of this program was to increase cultural sensitivity on the part of the Intel team. Also, to help blend the Intel and U.S. cultures into the acquired companies, we assigned a small senior leadership team to work in-country and alongside the acquired leadership team. Despite this blended approach, the situation became worse. The strong company culture of Intel began to fragment and dilute to the point where it became less of a competitive advantage.” Dunkin concluded from her extensive experience: “Cultural sensitivity is necessary, but only to a certain point. The point where it becomes counterproductive is when it begins to negatively affect a company's base culture. Company culture has to remain dominant over country cultures.”

Recent research supports Dunkin's opinion. It suggests that a strong company culture serves a utilitarian purpose as it tends to enable setting expectations, increasing the likelihood that when members of a team and other employees are faced with uncertainty, they will act in a consistent manner. A strong corporate culture sets the rules of engagement. Researchers have further demonstrated that within a group or team setting, when coordination is rewarded and when the group's or the team's culture is strong, its members become increasingly like-minded.34

The benefit of cultivating a robust and solid company culture is that it enables the establishment of common values and aligns employee behaviors. Multinational corporations use many means and avenues to build company culture, such as employee handouts, corporate ethics guidelines, written value definitions, new employee on boarding activities, and worldwide company meetings with all employees to instill and align employee values and behaviors. Additionally, in some multinational corporations, targeted hiring and employee self-selection leads to employees at company sites in other countries to become more in harmony with the respective corporate culture. Those employees who fit well stay with the company, and those who do not either do not get hired or leave after a period of time. Companies that nurture this approach may be able to maintain a consistent culture across their international locations.35

Converging Cultures

Rather than trying to blend cultures in a multinational organization and on a multinational project, it may be better to think in terms of converging the various cultures. Three primary steps are involved in the convergence of cultures:

- Establish a dominant cultural model where one ideology and set of behaviors is declared the official way of doing business.

- Establish an integration of team identity model that drives a common set of motives, ideas, values, and goals that members of the organization can all relate to.

- Maintain cultural awareness to recognize and respect the differences each culture brings to the organization and project team.

Dominant Culture

The establishment of a dominant cultural model is the most critical step of the three. Doing this involves formal recognition that company culture is the dominant one. All other cultures are subordinate. Since a company's culture is strongly influenced by the national culture where the company is headquartered or maintains its largest base of operations, the cultural norms of that nation will be dominant as well. Therefore, the way a multinational organization and its project teams operate is significantly influenced and driven by ideals and behaviors of the company. This is why there can never really be a merger of equals. Rather, one company has to remain dominant in order to establish a base set of operating principles. Those base operating principles guide the way the project teams conduct their work and interact with one another.

Integration of Team Identity

In order for multinational project teams to function effectively, however, their members must share a common set of goals, values, motives, and operating norms that they can all relate to and follow. We refer to this as integration of team identity. Within the company culture, the project team must establish its own project culture. The project culture is still dominated by the way the company does business, but it is modified by the cultural values and behaviors represented by nations participating on the project team.

As described earlier in this chapter and in Chapter 2, the team charter is a critical project artifact for any team, but especially so for a multinational, multicultural virtual team. Within the team charter, the team norms define how the team will interact and incorporate the cultural nuances of the team.

Continuous Cultural Awareness

The final step in the convergence of multiple cultures is continuous cultural awareness. Virtual project managers must be the champion for cultural awareness because at the project level, cultural awareness goes beyond just being aware of cultural differences between team members. Cultural awareness at the project level has everything to do with trust and relationships. As we discussed in Chapter 6, the project network on which a virtual team is built is held together by relationships, and trust is the foundation of those relationships. The cultural dichotomies discussed earlier and the variations in behavior that result from those dichotomies provide the opportunity for mistrust to arise when team members are culturally ignorant. For example, some team members may feel that addressing a problem or a source of conflict affecting the team is confrontational, but it is necessary to avoid distrust and fragmented relationships. Being culturally aware of the presence of these cultural issues allows project managers to work directly with affected individuals.

Different cultures rely on different mechanisms for deciding if other members on the team are trustworthy.36 People from some cultures assume everyone has good intentions until they prove otherwise. Others see trust as non-existent until earned. Some people gauge trust on other people's performance, while people from other cultures look for endorsement from a trusted third party to establish trustworthiness.

All these cultural differences are present in multinational enterprises and organizations. The convergence of the differences will occur where the “feet hit the street,” as the saying goes—at the project level. Cultural differences, of course, add more complexity to already complex virtual project environments. Much is left to virtual project managers to work and resolve while managing the project and leading the team. However, some significant organizational factors must be in place to assist an organization's virtual project managers. These organizational factors are discussed in the next two chapters.

Assessing Cross-Cultural Awareness

The Cross-Cultural Awareness Assessment measures the cultural awareness capabilities of a project team. The evaluators, organizational management, the project sponsor, and the virtual project team leader are responsible for evaluating and assessing the cultural competence on a project. Essentially, they are looking for a proper and balanced set of anticipated cultural skills that will raise the probability of success for team formation and interaction over the life of the project.

It is recommended that the members noted above complete the assessment. Once completed, meet to discuss results and findings as well as detail next steps (if warranted) to increase cross-cultural awareness.

Cross-Cultural Awareness Assessment

Date of Assessment: __________

Virtual Project Team Code Name: ________________________________

Virtual Project Manager Name: __________________________________

Project Start Date: _____________

Planned Completion Date: _____________

Team Size: ________ Number of Countries Represented: _________

Assessment Completed by: ____________________________________

Confidential Assessment: ______ Yes, confidential

______ No, not confidential

| Assessment Item | Yes or No | Notes for All No Responses |

| Project team members have participated in formal cultural awareness training. | ||

| The project consists of a high percentage of team members with prior experience working on cross-cultural project teams. | ||

| Project team members have country- and culture-specific knowledge and experience specific to the countries represented on the project. | ||

| Project team members have proficient (written and verbal) language skills in the primary language of the project. | ||

| Project team members have effective communication (especially listening) skills. | ||

| A cultural assessment has been performed for the project. | ||

| Cultural factors with wide variation within the team have been identified. | ||

| Cultural-based strategies have been developed for the project. | ||

| Project team members have confidence working with team members from other cultures. | ||

| Project team members have practical knowledge and ability to work successfully with power distance differences. | ||

| Project team members have practical knowledge and ability to work successfully with uncertainty avoidance differences. | ||

| Project team members are knowledgeable about and do not exhibit gender bias. | ||

| Project team members have practical knowledge and ability to work successfully regarding the cultural dimension of restraint. | ||

| Project team members have practical knowledge and ability to communicate in both low and high context settings. | ||

| The project team comprises both divergent and convergent thinkers. | ||

| A healthy level of assertiveness has been displayed in cross-team communication. | ||

| The project manager plans to visit all distributed work sites at least once per quarter. | ||

| Findings, Key Thoughts, and Recommendations | ||