CHAPTER 3

BUILDING A HIGH-PERFORMANCE VIRTUAL TEAM

It is well understood that the mission of any project is to create and deliver a solution that advances the business goals of the sponsoring company. It is also understood that there are two primary parts to any project: managing the project process and leading the project team. These fundamentals of project work exist in both traditional and virtual environments. However, how the project work is performed by the project team differs between the two environments.

As described in Chapter 2, management of the project process through a project management methodology with its associated practices, processes, and procedures does not change significantly between traditional and virtual projects. All projects must be initiated and planned to a certain scope of work and must be managed from cost, schedule, scope, risk, and change perspectives. In addition, work outcomes must be integrated to create a solution and then effectively brought to closure. Leading the project team, however, can vary vastly between traditional and virtual projects.

In essence, project team members perform their work in two ways: individual work and teamwork.1 People perform their individual work in identical fashion whether they are part of a traditional project or a virtual project. How they perform their work within the context of the team can differ significantly between the two types of projects, however. Effective teamwork is dependent on effective cross-member collaboration. Effective collaboration is in turn based on the establishment of professional relationships, trust between team members, clear roles and responsibilities, and appropriate communication forums to name a few of the important factors. For project managers of virtual teams, establishing effective teamwork has little to do with the science of project management and the hard project management skills they have developed and honed. Helping the virtual team collaborate in a new virtual paradigm relies heavily on the soft project manager skills, as they are often called, which include the art of leadership and the people skills that aren't learned and certified so easily. As managers know, the science of project management will fail quickly if project team interactions become dysfunctional. Project managers may realize early in the project cycle that the people skills that worked effectively on traditional project teams do not work as well for virtual teams. In fact, the separation of distance, time, and sometimes language and culture that defines a virtual team often requires project managers to focus more on team leadership and less on the fundamental science of project management. At the very least, project managers must have a clear understanding of the two distinct roles they must play—the role of project manager and the role of project team leader.

This distinction between the two roles of virtual project managers is not lost on Jeremy Bouchard. “While managing my first virtual project, it occurred to me that I overemphasized my knowledge and understanding of project management and that I woefully underestimated the importance of being an effective leader of the project team,” he explains. “For most of my career as a project manager, I've been very focused on project management methodologies and processes. You just sort of get on that track once you immerse yourself in project management. I let myself believe that my project management credentials were enough to carry me from project to project. All was good until I stepped into the world of virtual projects.”

Fortunately for Bouchard, he works for a person who understands that project management credentials are like table stakes that get you into a game of poker. They are necessary, but insufficient. His manager and mentor, Brent Norville, helped Bouchard learn that the balance of effort on a virtual project shifts from project management fundamentals to team leadership fundamentals. “It takes a while for a project manager with experience managing traditional projects to come to the realization that the project team has to be functional and perform as a unit in order for project management processes to be most effective,” Bouchard explains.

As Bouchard reflects, “Fortunately, my first virtual project wasn't very large or complex, so I was able to navigate through it with some great coaching from Brent. I now know that my team leadership skills and experience were weak. I still have a lot to learn, but now I understand the importance of the leadership role of the project manager. On my current project, which is also virtual, I have spent much more time building my team and focusing on being a strong leader. In the process, I've had to learn to delegate.

It bears repeating that success in managing virtual projects requires a high level of skills and competence in both project management and project team leadership. We described how the fundamentals of project management must be nuanced to translate into the world of virtual project management in Chapter 2. In this chapter, we turn our attention to the important nuances pertaining to the leadership of a virtual project team. We begin by looking at the most common types of virtual project teams.

Virtual Project Team Types

When people discuss the essentials of leading a project team, especially a virtual project team, much of the attention is centered on effective communication. Although communication is an essential part of all team dynamics, attention to people's feelings, priorities, and perceptions is also important, especially when we are trying to build a high-performance team.2 The managers of traditional projects have a distinct advantage when it comes to project leadership and the people side of a project because they interface directly with their team members and can rely on visual observations to determine personal and performance characteristics. This is not the case for virtual project managers.

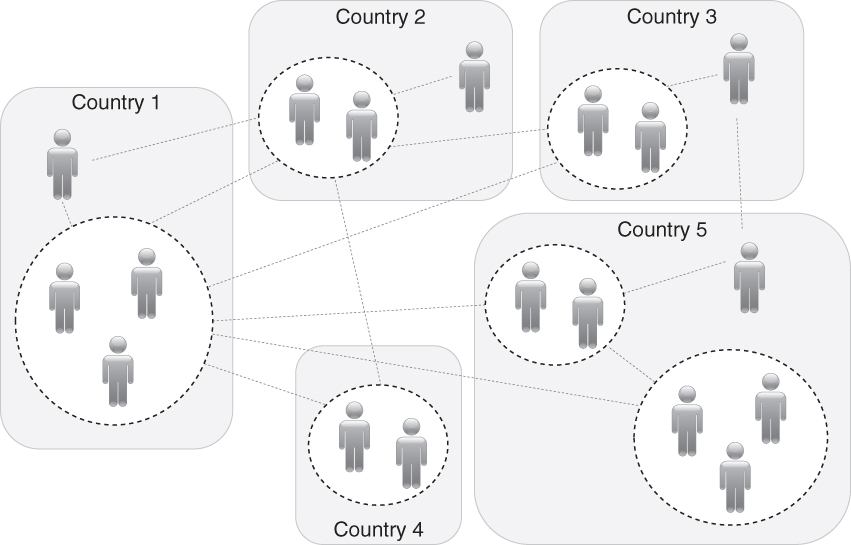

Virtual project managers quickly realize that the people skills that work well for traditional projects may not work as well on virtual projects. Traditional approaches must therefore be modified. The level of modification is dependent on the type of virtual team that is being managed. For this reason, we briefly describe five common virtual project team types:

- Mostly co-located, one central location

- Mostly co-located, multiple national locations

- Mostly co-located, multiple global locations

- Mostly virtual, nationally distributed

- Mostly virtual, globally distributed

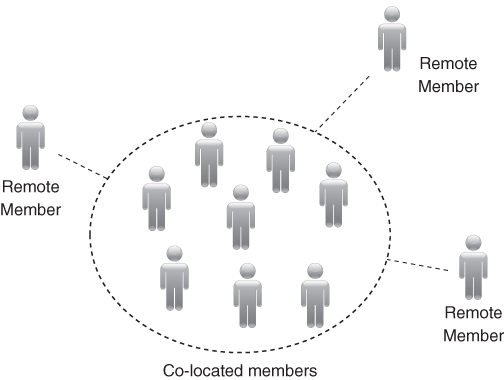

Figure 3.1 Mostly Co-located Virtual Project with One Central Location

Mostly Co-located, One Central Location Model

Becoming a virtual organization is often a journey, and many organizations begin with a virtual project team model where most of the team is concentrated in one or two locations with several members working from remote locations. (See Figure 3.1.)

This model is usually the result of hiring a few employees with very specialized skills who are located outside of the corporate geography and have reached agreement with the company to remain in their locations.

Because the large majority of team activity is concentrated at the centralized location, the remote team members face a constant challenge of staying tightly connected to the project as the large majority of team interactions are based on face-to-face exchanges between the co-located team members.

Building a high-performance team in this model is relatively similar to building a fully co-located team. The challenge, of course, is to ensure inclusion of the remote team members. Special attention and time is required to make sure that remote members fully identify as being part of the project team and interact in a seamless manner with the other team members, even though they have to do so using technology.

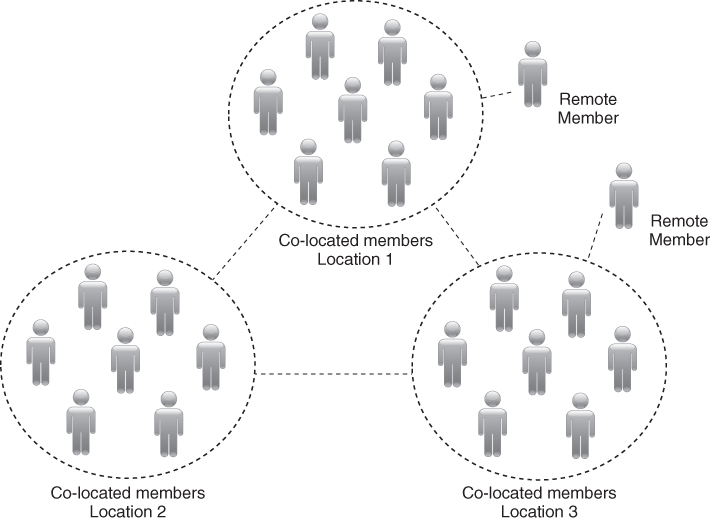

Mostly Co-located, Multiple National Locations Model

In the mostly co-located with multiple national locations virtual project team model, there are several geographic concentrations of team members, but all locations are in a single country. This model often emerges as a result of company acquisitions, business scale-up, or reorganization endeavors where multiple business centers are formed at the corporate level. Over time, work begins to integrate between business centers, and mostly co-located, multiple location project teams emerge. (See Figure 3.2.) It is also not uncommon for a few remote members with specialized skills to be part of the virtual project as well.

Figure 3.2 Mostly Co-located Nationally Virtual Project with Multiple Locations

The difficulty in building high-performance team increases with this virtual project team type due to the separation of organizational business units or divisions underlying this model. As stated earlier, this model often emerges as a result of a company acquisition or reorganization. Consequently, each location normally has its own management team, structure, and local business culture (culture being defined as “the way we do things” in this context). The difficulty, therefore, comes in building a common project team identity with team members who already possess a strong, but differing, organizational identity. In addition, project managers have to intentionally and purposefully work to build strong working relationships with key management stakeholders at each business location. A high-performance team cannot be built without the support of the organizational managers. These individuals will either be enablers or distractions to building the team.

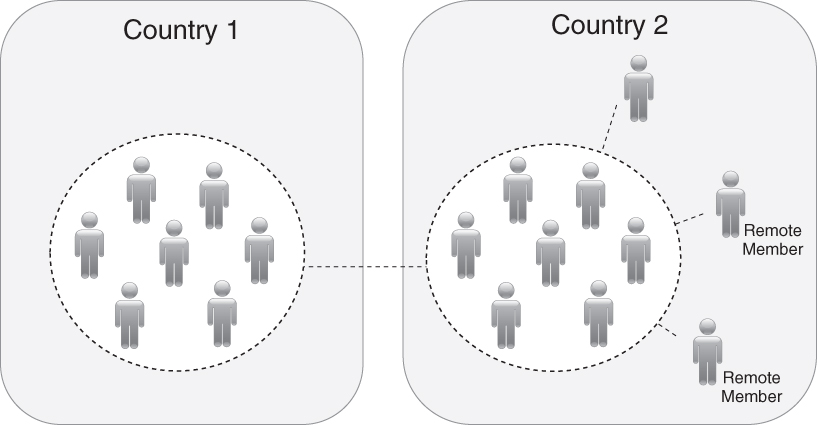

Mostly Co-located, Multiple Global Locations Model

Most companies today realize the benefits of conducting business on a global scale (or at least realize the competitive disadvantage of not doing so), so many business partnerships and business expansions occur in various parts of the world. This creates a global element to virtual project teams. In mostly co-located, multiple global locations virtual project teams, there are several locations of project team concentration in various parts of the world, as demonstrated in Figure 3.3.

The ability to build a high-performance project team in this virtual team model is hampered by differing cultural factors and large separation in time and distance between team members. Creating a common team identity becomes even more important in this model, but requires significantly more work on the part of project managers. Likewise, ensuring that effective team interaction is occurring across organizational, cultural, and national boundaries can be nearly a full-time job in itself; yet it is a job that is foundational to project success.

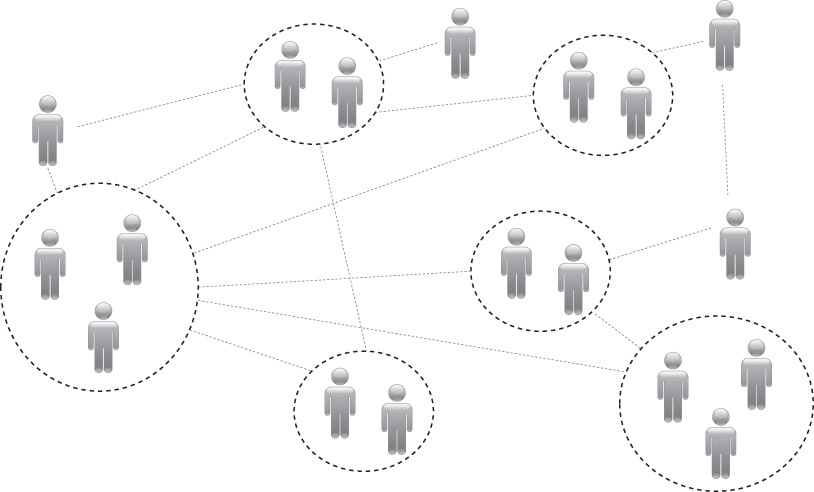

Mostly Virtual, Nationally Distributed Model

In the mostly virtual project team models, team members are geographically distributed in relatively equal fashion, as illustrated in Figure 3.4.

Some locations will include a larger concentration of team members than others, but it is not significant enough to tip the balance of team interaction to a mostly co-located model. What is prevalent instead is the lack of team member concentration found in the mostly co-located virtual project team models. Because project members are not concentrated in a few locations, building a high-performance project team is in many ways easier because members are in parity without being encumbered by organization and management hierarchy issues. Team members often seek team identity as a substitute for weak organizational identity and tend to look for coworkers who share a common purpose for their efforts and contributions to the organization.

Figure 3.3 Mostly Co-located Virtual Project with Multiple Global Locations

Figure 3.4 Mostly Virtual Project with Nationally Distributed Project Team

Geographic separation limits face-to-face interactions; therefore, communication, collaboration, and relationship building has to occur via technology. And importantly, cross-team interactions normally have to be facilitated at least initially by virtual project managers. Again, ensuring that the interactions occur requires more time and attention.

Mostly Virtual, Globally Distributed Model

Adding the global element to the mostly virtual project team model brings with it the complexities associated with multiple national cultures, multiple first languages, and a greater degree of separation in time and distance between team members. This model is very much a hybrid between the mostly co-located, globally distributed and the virtual, nationally distributed project team models that combines both the benefits and challenges of the two models. (See Figure 3.5.)

Figure 3.5 Mostly Virtual Project with Globally Distributed Project Team

Because team members are not strongly connected to a centralized location, they are often eager to establish a connection and identity to a project team. In many cases, the project team identity becomes their company identity.

However, significant effort on the part of project managers is required to initiate team interactions and to facilitate cultural nuances that will occur within the team. As we cover in detail in Chapter 8, selection of the right technologies that enable effective team communication, collaborative interaction, and relationship building is critically important and largely the responsibility of project managers.

Much has been written about achieving high-performance teams. No doubt, achieving high performance is a combination of both management and leadership factors regardless of whether the project team is traditionally structured or has some type of virtual structure. Those enterprises that can achieve higher-performing virtual project teams will possess a significant competitive advantage. But what does it take to build a high-performing team? Answering that question must start with a discussion on the foundational elements of teamwork.

Differentiating High-Performance

Let us begin by distinguishing between a work group and a team. Both a work group and a team can be defined as a group of people working together to accomplish an objective or goal. The difference between the two comes in understanding the interaction between people. A work group can achieve its objectives by its members working separately and independently, such as the members of a project management office. By contrast, a project team provides a collective work product and a performance gain or improvement that is not achievable by group members working on their own. If it is a project team, then it is represented by a set of team members working under the direction of a project manager and performing project work to achieve the project objectives.3

How effective a project team is depends on how well members work together in creating the work product and achieving the project objectives. This is commonly known as teamwork. A good working definition of teamwork is “the process of working collaboratively with a group of people in order to achieve a common goal.”4

Good teamwork is rooted by a set of shared values that enables important behaviors including listening and constructively responding to the points of view of other team members, providing support to each other on the team, and being positive and supportive to the accomplishments of others on the team.5 Teamwork is further encouraged and achieved during the life of the project through good communication and collaboration practices, mutual respect, appropriate processes, and clarity in decision making procedures.

Not all project teams are created equal. All projects consist of a team of people who perform the work intended. Some project teams seem to consistently perform at a higher level than others. A high-performance team is one that consistently exceeds the expectations of customers, sponsors, and senior management. Normally, what comes to mind when most of us think of high-performance teams is a sense of accomplishment that goes beyond expectations. Jon Katzenbach, a leading author and practitioner in organizational strategies, accurately describes a high-performance team as “a group that meets all the conditions of real teams, and has members who are also deeply committed to each other's personal growth and success. That commitment usually transcends the team and the team has internalized the philosophy that if one of us fails, we all fail.”6 It is not easy to assemble and create a high-performance team however, and most organizations struggle to build teams that can consistently exceed expectations. Teams of this caliber are rare.

High-performing teams develop a keen sense of shared accountability and responsibility for the overall success of the project. This sense of joint responsibility is interpreted as not only fulfilling their own individual and personal commitment to the team, but also making sure that all team members are successful. Shared responsibility works best if everyone on the team is clear about their own responsibilities, as well as joint responsibilities, and fully understands the success factors and objectives of the project. Of course, high-performance teams do not just form by themselves. All high-performance teams share a common element: a project manager who also performs as an exceptional team leader. High-performance teams have to be built and sustained, and those that achieve high-performance status are led by people who have a good balance between project management and project leadership capabilities. In short, high-performance teams are intentionally designed and well led.

What prevents all project teams from becoming high-performance teams? Some believe that if you add your top talent and best performers to a team, it can't help but be successful—the “dream team,” if you will. Most of us have seen that this rarely works on its own. Usually some underlying fundamental principles of team building have been ignored or left unaddressed when forming the team. In other cases, organizational issues or barriers may exist that hamper or do not enable the team's ability to perform.

Many authors have tackled the subject of characterizing high-performance teams. Probably two of the foremost experts are Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith. In their book Wisdom of Teams, they cite five key criteria possessed by teams performing at a higher level than average or even good teams. These include:

- A deeper sense of purpose

- Relatively more ambitious goals

- Better work approaches

- Mutual accountability

- Complementary skill set (and, at times, interchangeable skills)

They point out further that high-performance teams have a unique quality in that the team members have a basic need and an ambition to go after bigger challenges. Consequently, they bring with them a work ethic that creates a deeper commitment to the collective mission.7

As a result of our own experience leading project teams, we feel there are a number of other critical characteristics exhibited by high-performing teams that should be pointed out:

- The presence of a shared vision and objectives

- Participative leadership

- Well-defined roles, responsibilities, and expectations

- Action-oriented team members

- Trust between team members

- Managed conflict

High-performance project teams can be a marvel to observe. It is evident, even to casual observers, that members of high-performance teams possess a passion and energy for exceptional work outcomes. It is this bias for excellence that binds employees together across both hierarchy and geography and guides them to make the right decisions and advance the business without explicit direction to do so.8

Building a High-Performance Virtual Project Team

Despite the ever-present challenges to building a virtual project team that performs at a high level on a consistent basis, there is good news for virtual project managers. Many of the foundational elements of building a high-performance team are the same for both traditional and virtual teams. The major difference is in how these elements have to be applied when the team is geographically distributed.

We admire the quote by the British statistician George Box, who stated, “All models are wrong, some are useful.” One such model that we find tremendously helpful in building a high-performance virtual project team is what is commonly referred to as the Tuckman development model. Defined by Bruce Tuckman in 1965, the model describes four stages of development that a team normally progresses through: forming, storming, norming, and performing. Although decades old, this model of team development still serves as an excellent base for understanding what must transpire in the establishment of a virtual project team (see box titled “Challenges to Developing a High-Performing Virtual Team”). In particular, Tuckman's forming and storming phases offer considerable understanding as to how teams evolve in the early stages of a project and establish the foundation for high-performance later in the project.

The forming stage is especially critical as this is the time when team members get acquainted with one another and gain knowledge and understanding of the expectations for their participation on the team. Team members are also eager to learn about the project requirements and deliverables.

In Tuckman's storming stage of team development, team members begin to understand their respective roles, responsibilities, and dependencies on each other and how they might, as individuals, need to bend and change their ideas, attitudes, and approaches to adhere to the group.10 Conflicts may begin to occur, which gives rise to the opportunity to begin directly working through the conflicts, a fundamental element of high-performing teams. We suggest that all virtual project managers either familiarize or refamiliarize themselves with the early stages of the Tuckman model. It can serve as a good tool for establishing a firm understanding of the team dynamics that are present during the formation of every virtual project team.

Effective Team Formation

Team formation for virtual project teams is particularly challenging. Project managers of traditional projects have a distinct advantage over their virtual project counterparts in regard to forming their project team. For traditional projects, team leaders often are aware of the capabilities and personalities of many, if not all, individuals who are candidate team members. Additionally, these leaders have had an opportunity to build relationships with the functional managers who decide who will be assigned to what project and therefore can influence those decisions. Virtual project managers rarely possess these advantages and must try to form high-performance teams without knowing the capabilities and qualities of the people assigned to them.

One of the foundational elements of a high-performance team is mutual trust, both among team members and between team members and the project leader. The limits of the technologies used in the communication and collaboration needed between geographically separated team members normally constrains building the much-needed trust and shared understanding of all aspects of the project. Research has shown that relationships, trust, and team identity can be effectively created and formed on virtual project teams, but at a slower pace than for co-located teams. There is no doubt that it is considerably easier and faster for co-located teams to build relationships using face-to-face meetings and interactions. Most virtual teams have limited to no access to this major team-building advantage.11

Teams also rely on understanding and internalizing the various sources of project information as part of the team formation process. A traditional team has a high level of social presence that facilitates the sharing of information, especially in the forming of the team. It is much more difficult in the virtual team environment to share and gain access to virtual project team data and information. Considerably more effort and effective electronic systems are required to have project documentation and other information readily available to all team members. Sufficient discussion must occur to reach a common acceptance and internalization of project information as a team. The next box, titled “Eva's Virtual Project Team Formation Template,” is an example of how one virtual project manager approached the formation process for her project.

Creating a Common Purpose

Bringing a group of people together and assembling them as a team does not make them think and behave as a team. Members of a team must view their work in terms of we instead of me; in other words, they must think: We must work together toward a common purpose that is defined by a set of common and agreed-on business and project goals. Project managers must establish the common purpose and inspire the team to work collaboratively to achieve the goals that define that purpose. The ability of project managers to create a common vision and the team's willingness to adopt that vision is what defines a group of people as a team. For a virtual project, the need for a well-defined common purpose is amplified because it is the foundation on which building team cohesion is based.

When a virtual project team is formed, team members usually have very little in common. At times, as in the case of a merger or acquisition of companies, team members may not have worked together previously. Additionally, in a merger or acquisition, team members have very idiosyncratic ways of thinking and behaving within the cultural and functional norms of their own company. At times they place their own personal goals ahead of team goals. Without a clearly articulated common purpose for the project and project team, a large degree of ambiguity and lack of focus can exist within virtual teams. A clearly articulated common purpose is a virtual project manager's most valuable tool for driving ambiguity out of the environment and getting team members to think of team goals ahead of personal goals.

A clearly defined common purpose should answer four key questions:

- What is the purpose of this team—the mission?

- What does the end state look like—the vision?

- What do we need to accomplish to get to the end state—the objectives?

- How will success be measured—the success factors?

The job of virtual project managers is to create answers to these four foundational questions with input from team members and stakeholders. Answers should be simple, direct, and free from jargon to overcome competing cultures and mind-sets and to address both corporate needs and local conditions. Creating the answers to these four questions is the first step toward getting team members to think and behave collectively instead of individually.

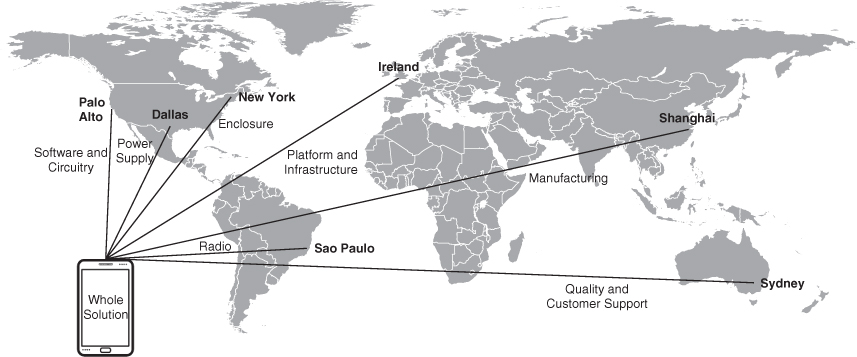

Figure 3.7 Distributed Whole Solution

In Chapter 2, we introduced the whole solution as a means for project managers to establish both a common mission and a vision for their project teams. The whole solution is defined simply as “the integrated solution that fulfills the customers' expectations.”12 Integrated is the key word in this definition. This word tells us that customers' expectations cannot be fulfilled by any one specialist or set of specialists on the team. Rather, success comes when meeting customer expectations is a shared responsibility between project team members, with their work tightly interwoven and driven toward an integrated customer solution.

By creating the whole-solution diagram, a visual representation of the integrated solution that will meet the customers' expectations emerges. An effective illustration of the whole solution occurs when each member of the project team can see how their work contributes to the creation and delivery of the integrated solution. The whole-solution diagram also allows project team members to see what work is done where, geographically. In the example depicted in Figure 3.7, product software and circuitry is provided by the team in Palo Alto, California; the power supply team is in Dallas, Texas; enclosure work is performed by the New York team; platform and infrastructure is managed by the Ireland team; radio and other telephony services is provided by the Sao Paulo team; manufacturing is conducted in Shanghai; and quality control and customer support is the responsibility of the Sydney team.

A whole-solution illustration becomes central to establishing a common vision and serves as a guidepost for project team members to understand what work the team collectively needs to do on the project. When a team is distributed and works virtually, it has a more difficult time seeing itself as a whole that is working collaboratively toward common goals. Each team member needs to be able to see how their actions and those of others contribute to goals—how individuals impact the collective.

The whole solution, however, is merely the means to achieve the business results that are driving the need for the project. Clear definition of the business results form the answer to the third question in creating a common purpose—what are the project objectives? In the example above, the project objectives may be to increase market share, increase profit margin, lower product cost, and accelerate time-to-market introduction. By defining and documenting the project objectives, members of the virtual project team begin to focus on the things that can be achieved only by the collective success of the team.

It is not sufficient to define just the project objectives when establishing a common purpose for a project. The final step comes in defining the project success measures. Specifically, the success measures must define how the project objectives will be measured. For the example used previously, project success may be measured by an increase of 5% market share, 2% increase in profit margin, $50 decrease in product cost, and market introduction in the fourth quarter of the year. As with the objectives themselves, it is clear that the success measures can be achieved only by the collective success of the project team.

Creating Team Chemistry

A project team may consist of the top talent within an organization, but they will not reach a high level of performance without a certain bonding of spirit and purpose. It is this bonding, or team chemistry, that motivates team members to work together collaboratively for the common success of the team.

Of course, when a group of people form a team, their personalities do not gel immediately. Acculturation of personalities, ideas, shared values, and goal alignment takes time as well as intentional effort (sometimes considerable effort) on the part of project managers.

People from diverse backgrounds and experiences will bring different behaviors, routines, values, and ideas about the work of the team. Team leaders must embrace this diversity of people on the team as individual members who make up a collective work unit, and they must act as coaches and role models for the rest of the team to help them embrace the value of diversity. Chemistry will evolve from how well each team member bonds to others on the team and how much each is willing to contribute to make the team a success. No doubt, project teams with excellent chemistry between the team members are much more productive and achieve higher levels of performance.

Establishing team chemistry on a virtual project is complicated because of cultural diversity, lack of social presence, and increase in communication challenges due to language and time zone barriers brought about by the team's geographic distribution. As a result, when team members represent diverse backgrounds, converging national, organizational, and functional cultures into a team culture where values, attitudes, and meanings come together takes more time. On a widely distributed team, it is also more difficult to get to know people on a personal basis and to form close relationships due to the limited amount of ongoing face-to-face interaction. However, both the blending of culture and development of personal relationships are critical for the team to behave cohesively and consistently as a team instead of as individuals.13

Successful virtual project managers do a number of things to accelerate the establishment of team chemistry. These include establishing clear roles and responsibilities, fostering social presence, using information-rich communication technologies, and celebrating team successes.

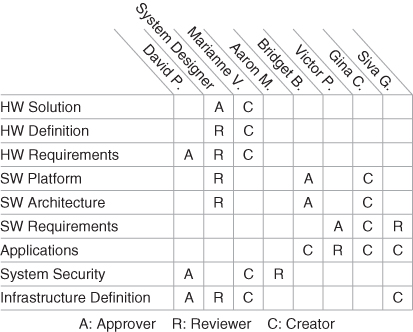

Establish Clear Roles and Responsibilities

A project team cannot achieve a state of high performance without a clear understanding of who is responsible for what. For traditional projects, this clarity often can be achieved through informal and formal conversations. That is not the case for virtual project teams. Team member roles and responsibilities have to be explicitly documented and communicated on the virtual project; a simple responsibility matrix, as shown in Figure 3.8, is often all that is needed.14

Figure 3.8 Example Project Responsibility Matrix

Ultimately, virtual project managers are responsible for the various outcomes and outputs associated with a project as well as the successful achievement of the success factors. However, along the way, responsibility for the satisfactory completion of work is a shared responsibility between the project team members. (See the box titled “Virtual Roles and Responsibilities.”) A best practice among virtual project managers is to use a responsibility matrix to explicitly demonstrate how responsibility will be delegated and shared on the project to remove implied assumptions on the part of the project team members and stakeholders about who is to do what.15

Foster Social Presence

To prevent some members of the virtual team from becoming invisible, make sure that all team members know one another and continue to foster connections. The best scenario for developing and establishing these foundational elements, given the time and distance barriers associated with distributed virtual teams, is through one or more early face-to-face team meetings. Unfortunately, many virtual teams have little to no face-to-face team involvement, which can limit and slow effective virtual team development. It is important for senior leaders to realize that investing company financial resources to bring teams up to speed more rapidly and to increase the potential for achieving higher levels of virtual team performance is well worth the investment.

A recent study by Deloitte pointed out that “virtual teams should not discount the importance of face-to-face interactions with the client and the onsite team. Teams may consider rotating offsite resources onsite to enable them to have client-facing interactions and get to know the rest of their team in person.” Deloitte further pointed out that after the rotation, these resources typically are more effective due to the deeper relationships that have been formed.16 Many organizations have found it beneficial to invest initially in face-to-face team meetings during early team formation and also provide the opportunity to spend some time on building relationships.17

However, face-to-face team meetings are not always financially possible. The fallback position is to accomplish these early formative interactions through audio or video conference sessions. These sessions, of course, must be followed up with periodic visits and meetings on a consistent basis between project managers and team members. It is important for project managers to set the tone and perspective by getting face-to-face with team members. Doing this allows team members to visualize project managers and create a visual frame of reference that will carry forward and be projected on future audio and written communications. Nothing can fully compensate for the inability to see a person's body language while communicating with them, but having a visual frame of reference helps tremendously in furthering social presence with a team.

With face-to-face interactions being rare on virtual projects, the team must be able to use communication and collaboration technologies that enable them to continue building relationships and rapport. Video conferencing, either roombased or desktop based, is a good example of an information-rich technology that will help to continue to foster social presence. Additionally, some virtual project managers have created simple social networking websites for their teams that provide member profiles. (More on these technologies in Chapter 8.)

Celebrate Success as a Team

Making sure that the entire team participates in team celebrations goes a long way toward focusing team members on team accomplishments over individual accomplishments. The celebrations do not have to be large or even formal in nature to be appreciated by team members. Successful virtual project managers look for additional opportunities to recognize team accomplishments throughout the duration of the project at key milestones, major events, and even as surprises to the team to help alleviate anxiety and pressures.

Building Trust

Trust must exist between project managers and team members and between team members themselves if a high level of performance is to be achieved. Several factors are important to the establishment and sustainment of trust. These factors include open and honest communication, having no fear of reprimand or reprisal, and confidence that conflicts will be dealt with successfully and properly.

In his book The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership, John Maxwell uses the analogy of building trust as either putting change into your pocket or paying it out.18 Each time project managers form a new team, they begin with a certain amount of change in their pocket, representing the inherent trust a person receives from his or her position as the team leader. As the project progresses, team leaders either continue to accumulate change in their pocket by building trust or find that the pocket begins to empty when trust is depleting.

This analogy holds true for leaders of virtual project teams as well, but there is a distinct difference. Because of the geographic separation and cultural differences inherent in a virtual team, project managers and team members may find their pockets completely empty of change at the beginning of the project—meaning that a virtual team may begin collaborating within an environment that is completely lacking trust. For traditional teams, some trust may exist based solely on social bonds that are in place given their co-location and commonality in culture. Virtual teams do not have this social bond as a foundation of trust to build on. Trust in a virtual environment is granted to those who demonstrate they are trustworthy; therefore, it is based more on consistent and proven performance by both virtual project manager and team members than on social bonds.

Table 3.1 lists the factors that both destroy and create trust on a project team. Obviously, the team leader is best served by acting on the trust creators and avoiding the trust destroyers.

Table 3.1 Trust Creators and Destroyers

| Trust Creators | Trust Destroyers |

| Act with integrity | Demonstrate inconsistency between words and actions |

| Communicate openly and honestly | Withhold information or support |

| Focus the team on shared goals | Put personal gain over team gain |

| Show respect to team members as equal partners | Listen with a closed mind |

Table 3.2 Team Norms

| Team Category | Example Norm |

| Personal behavior | Always treat other team members with professional courtesy and respect. |

| Communication protocols | For voice communication the team will use Skype technology.For text messaging, the team will use Skype or Windows Live Messenger. |

| Commitment | Set and adhere to commitments made and agreed to by the due date, assisting other team members when requested, and don't surprise the project manager with missed commitments. |

| Conflicts | Conflicts will be identified and discussed with team members involved. Viable alternatives and solutions will be developed and discussed. Conflicts will be resolved in a timely, positive, and constructive manner |

| Meetings | Meetings will begin on time. There will be a set and prepublished agenda. Meeting notes will be created and distributed. |

| Decision making | Decisions will be made in a consultative manner with one decision maker appointed. |

| Consent | Disagreements must be voiced and discussed, silence means consent. |

| Respect | No put-downs, either in foreground or background discussions, will be directed toward fellow team members. |

| Timeliness | Voicemails and emails must be returned within 24 hours and team members will own the timeliness and quality of our work. |

| Bias toward action | Team members will lend support, raise concerns, and praise great work in a proactive manner. |

| Celebrate success | Both large and small successes will be celebrated to recognize accomplishments. |

Building strong relationships between team members is also an important factor in enhancing and sustaining trust on virtual project teams, especially later in the team's life. Because of geographic separation, creating and sustaining trust on virtual teams requires a more conscious and planned effort on the part of project managers. At a minimum, it requires managers to spend more time networking and traveling across geographic boundaries.

Establishing Team Norms

A project team can never reach a state of high performance if it does not perform and interact in a consistent manner. Consistency comes from establishing and following a set of team norms that should be established in the early stages of team formation (ideally be documented in the team charter). Norms are the rules and guidelines that a team agrees to follow as it conducts its work.19

On traditional projects, team norms generally are unwritten and engrained in the organizational culture. For virtual projects, establishing team norms needs to be more deliberate. The norms need to be put in writing and to be reviewed on a periodic basis. Once developed, agreed upon, and implemented, team norms begin to guide the behavior and interpersonal interactions of team members and build team discipline, trust between members, and predictability in behavior. These established norms contribute to a solid foundation for the project team; if these norms are not agreed to and implemented, there is a greater probability for potential misunderstanding and conflict between team members.

Virtual project managers will find it beneficial to begin with an initial set of norms. Although team norms are unique to organizations and specific projects, Table 3.2 provides examples that are common for high-performance teams.

The team should also recognize that the team norms are set based on what is known by the team and team leader at the time of project initiation. As the project progresses, team norms may need to be adjusted, and new ones may need to be established and implemented.

Empowering the Team

With leadership comes power. The most effective project managers and team leaders are those who are willing to share their power with those team members who can make the most positive impact. As trust develops on a project team, project managers should begin to delegate some power to other key team leaders by empowering them. Empowerment is the sharing of power from one person to another and granting others influence and authority to take responsibility and make decisions within their sphere of work. As explained previously, team empowerment means giving the project team members the responsibility and authority to make decisions at the local level. In their book The Power of Product Platforms, Marc Meyer and Alvin Lehnerd state: “There is no organizational sin more demoralizing to teams than lack of empowerment.”20

As team members are granted greater power, they will begin to act more independently and rely less on the direction of the team leader. They will take on a greater sense of responsibility for their work output, become more comfortable with making decisions and solving problems on their own, begin to act proactively instead of reactively, and ultimately become more motivated to succeed. Empowerment of virtual team members motivates and encourages them to work, make decisions, solve specific problems facing their team assignments, and take the necessary actions autonomously through self-management.21 Without empowerment to decide and act, virtual team members simply wait, usually in frustration, until decisions are made and passed down to them. This waiting is inefficient, ineffective, and demoralizing.

Team member empowerment is arguably more critical on virtual projects than on traditional ones as it is an effective tool for quick and effective decision making, where people closest to an issue are most suited and able to evaluate the situation and decide the proper course of action. Greater discussion on team empowerment is provided in Chapter 6.

Selecting the Right Team Leader

For virtual teams to operate at a high level of performance and ultimately succeed in their mission, strong leadership from project managers is a must. Although the skills and abilities project team leaders need for traditional projects are similar to those needed for virtual projects, there are a number of differences due to the fact that virtual teams have challenges caused by differences in location, time zones, and culture. The key to overcoming these challenges rests in large part on the shoulders of project managers as they fill the role of team leader.

Senior managers must do their best to select project managers who have the ability and the experience to build a high-performance team. When selecting a leader, effort should be made to select people with the ability to balance both the execution-oriented practices and the leadership practices that define virtual project work. More than anything, these all-too-common practices should be avoided: selecting the first person to volunteer for the position; selecting one who has success leading only traditional teams; selecting managers based only on certification, “entitled experts,” or the best technical skills.22

Selecting the right team leader for a virtual project begins with understanding key characteristics that effective virtual project team leaders possess. Listed next are core characteristics that should be sought out when considering individuals to take on the leadership role of a virtual project team. Team leaders should:

- Be comfortable working in an unstructured and at times ambiguous environment.

- Motivate others to achieve results.

- Delegate work and responsibilities effectively.

- Provide effective governance without micromanaging individuals.

- Demonstrate strong communication, provide clear direction, and are responsive.

- Effectively manage conflict.

- Recognize and rewards others.

Most important, effective team leaders inspire personnel to collaborate as a team regardless if they are co-located or distributed. They inspire and motivate their teams to achieve not only the best level of individual performance but also to relegate their individual performance to that of greater team performance. They do this by communicating higher expectations of the team through the efforts of the individuals. Effective and inspirational communication transcends time, distance, and cultural barriers.

Adjusting Team Membership

When asked about the team member selection process for his virtual project teams, Kirk Rheinhold, the assigned project manager, presented a situation that is common in many organizations. “I have little influence on who is actually assigned to my project team, especially on projects that have team members from multiple company sites,” he explained. With virtual teams, especially teams that are widely distributed or consist of members from multiple companies, virtual project managers rarely have influence over who is initially assigned to work on their project.

The difficulty with this reality of modern project life is that the ability to build a high-performing team is highly dependent on who is on the team, their personalities, how well they work as team members, and their work ethic. When a virtual project team is formed by people other than the project manager, these performance dependencies are unknown.

This does not mean, however, that project managers are powerless, as Rheinhold explains: “I go into a new team with the base assumption that some level of adjustment to team membership will be needed. The project manager must be able to quickly assess the abilities of the team members to effectively work in a virtual team environment. Then if problems exist, they must take it upon themselves to drive for change in membership or work with line managers to have the necessary training, mentoring, and coaching provided.”

Personal attributes needed for a person to work well in a virtual project environment are normally not well understood within an organization. It is just assumed that anyone can work virtually. As a result, project team members are seldom screened for virtual attributes during the team member selection process. In particular, virtual team members must be considerably more self-sufficient than their counterparts on traditional project teams who can more easily seek help in their team environment. Virtual team members also must be able to tolerate ambiguity better than members of traditional teams due to the additional lack of clarity and other complexities caused by the time and distance issues associated with highly distributed teams.23

Virtual team members must also be able to keep their emotions in check. Emotionally charged communications lack context and, as a result, often become a source of miscommunication and conflict in the virtual environment. In such environments, emotions should be employed to enable and improve reasoning during problem solving and decision making and to positively affect the emotions of others.

Virtual project teams rely a great deal on technology to communicate, collaborate, and perform their work. Therefore, technological sophistication is required of all team members. Members must be willing and able to adapt to and use new technologies meant to enhance team communication and collaboration.

Finally, virtual project team members must always be willing to share information with their fellow team members. Transparency of information is a keystone factor in raising a team's performance level team. The distributed team model provides ample opportunity for information to be kept local, so the team members themselves must be motivated to ensure that their information is widely distributed and available to other team members and stakeholders.

These are a few of the critical personal attributes to look for in virtual team members, but there are others that virtual project managers can identify as necessary for their teams. The burden of assessing team members' ability to perform on a virtual team and of making personnel changes when necessary rests with project managers. An assessment tool is provided to assist virtual project managers in assessing team members.

Assessing Virtual Project Team Members

The Virtual Project Team Member Assessment is used by organizational management and virtual project managers to evaluate and select team members to serve on virtual project teams. The assessment is divided into two sets of criteria. The first set of criteria, Basic Criteria, represent capabilities that are basic to all teams, both co-located and virtual. The second set of criteria, Virtual Team Criteria, is intended to assess the capability and experience level of potential team members.

Each possible virtual project team member can be evaluated separately. To evaluate each candidate, project managers and other leaders should compare assessment results with one another. People should be offered virtual project team member positions based on their individual potential for successfully achieving the project objectives and senior management expectations for the project. The sample assessment included can serve as a baseline for a customized assessment that fits specific organizational needs.

Virtual Project Team Member Assessment

Date of Assessment: __________

Candidate Team Member Name: __________________________________

Virtual Project Team Leader Name: ________________________________

Assessment Completed by: _____________________________________

Estimated Size of Team: __________ Number of Team Sites: _________

Confidential Assessment: ______Yes, confidential

______ No, not confidential

| Assessment Item | Yes or No | Notes for All No Responses |

| Basic Criteria | ||

| The candidate has proven technical or specialist skills to contribute to the project team. | ||

| The candidate has proven project management skills. | ||

| The candidate has proven problem-solving skills. | ||

| The candidate has successfully participated on or led co-located project teams. | ||

| The candidate has demonstrated self-motivation and ability to perform self-directed work. | ||

| The candidate has a track record of ethical behavior. | ||

| The candidate has proven to be reliable and dependable. | ||

| The candidate has demonstrated personal confidence in his or her work. | ||

| The candidate has a track record of trustworthiness. | ||

| The candidate demonstrates a positive attitude. | ||

| The candidate has a proven track record of meeting his or her commitments. | ||

| The candidate has demonstrated the willingness to share project information. | ||

| Virtual Project Team Criteria | ||

| The candidate has prior experience with virtual teams. | ||

| The candidate has prior international experience. | ||

| The candidate has proven ability to deal with ambiguity. | ||

| The candidate has proven networking skills. | ||

| The candidate communicates concisely and clearly. | ||

| The candidate is sufficiently proficient in the language of the project. | ||

| The candidate is proficient in other languages besides the language of the project. | ||

| The candidate has proven proficiency with electronic communication technology. | ||

| The candidate has proven ability to work independently. | ||

| The candidate has the ability to cope with isolation from rest of team. | ||

| Findings, Key Thoughts, and Recommendations | ||