CHAPTER 2

PLANNING THE VIRTUAL PROJECT

There was a lot of excitement at this month's portfolio review meeting at Sensor Dynamics. The company's researchers achieved a technological breakthrough that provides a pathway into the new autonomous automobile market. It was believed that the technology was ready to go into a product, and strong interest had been expressed by both new players in the auto industry, and a few large technology companies, and historic automobile manufacturers. Sensor Dynamics received a commitment from a Japanese automobile manufacturer to sign on as a strategic partner. The portfolio team at Sensor Dynamics approved the development of the new sensor product, code named “Sitka,” and added it to the company's new product development portfolio.

Jude Ames, Vice President of New Product Development, turned to Brent Norville and asked an important question: “Do you have a PM and team that you can put on this project now?” The obvious answer was no because every project manager and team were currently committed to projects, but Norville knew this answer would not be acceptable. “Everyone is committed to a project right now,” began Norville, “but Jeremy Bouchard's team will be launching their biometric product in three weeks, so we can probably move the entire team over to the Sitka project. In fact, Jeremy and a few of the project leads could begin early initiation and planning work next week.”

As all good senior executives know how to do, Ames asked another important question: “Is that the right team to put on this project? Success is critical.” Norville was aware that Bouchard had some challenges moving into a role of managing virtual projects, but much of that had to do with the situation in which he was put. In particular, his problems had arisen when he was asked to manage a project and team that was highly distributed and a team that had not worked together in the past. By keeping the team together for the Sitka project, Bouchard and his people would be in a much better position this time to begin performing immediately. “By keeping the virtual project team mostly intact, Jeremy should be able to get the Sitka team formed quickly and get them focused on project planning,” Norville stated. “The challenge will be bringing the Japanese auto partner into the team and integrating the new technologists from our research facility in Europe,” he added.

Bouchard welcomed the opportunity to begin initiating the Sitka project, particularly since much of the Sitka project team would consist of people he has had on his team for the past 18 months. “On my first virtual project, I was overwhelmed during the planning phase because I really didn't understand the amount of effort that is required to form a virtual project team,” explains Bouchard. “It's truly like having two full-time jobs—planning the project and forming the project team.” Like Bouchard, many project managers experience the shift in the amount of effort required to fulfill this dual role when they move from managing traditional projects to managing virtual projects.

Even though the terms project manager and project leader are used interchangeably, it is important for project managers to understand that the work associated with the two roles is not interchangeable. To help delineate between the two roles, remembering the distinction described by author John Maxwell is helpful: “Managers work with processes and leaders work with people.”1 Obviously, project managers do both. As Jeremy Bouchard reflected, this is especially true and important during early initiating and planning of a virtual project. Knowing where to focus your efforts in each of the two roles in order to gain maximum value for those efforts is the subject of this chapter and the next one.

Planning a Virtual Project

Chapter 1 described the primary differences between virtual and traditional projects that have to be considered specifically when managing a virtual project. These differences do not take long to emerge and for their effects to be felt. Most, if not all, emerge when a project is in the earliest stages of the project life cycle, as described in the next box.

Regardless of whether the life cycle used is predictive, iterative, incremental, or adaptive, the phases generally are sequential and are broken down by objectives, deliverables, milestones, scope of work, or investment allocation. Importantly, each phase is time bound, which emphasizes a control point for each phase (or investment). The detail of any life cycle (number of phases and description of each phase) is often determined by organizational culture, risk tolerance, and project discipline maturity. The project life cycle serves as the framework for managing the project. Thus, an appropriate level of structure must be applied. Too much structure can bog the project team's effort down in bureaucracy. Too little structure, and the team can drift outside of scope and miss business goals.

Most individuals who have been part of a virtual project know the challenges very well. Some, however, may be wondering what all the fuss is about and why virtual projects are so much more difficult than traditional projects. To understand the challenge, let's use an example in which effective communication is of paramount value, as is the case with any project, large or small, traditional or virtual. Think of the game commonly referred to as the Telephone Game. You may recognize this game by one of its other names, such as Chinese Whispers, Russian Scandal, and Secret Message. The game goes like this: One person whispers a message or story to another person, who in turn passes the message (or at least what was heard as the message) to another person, who in turn passes the message to another person, and so on until the point when everyone in the game has heard the message—or, perhaps more specifically, heard a message. To conclude the game, the last person says to first, or to the entire group, what he or she heard as the message.

As can be expected, errors in the message accumulate as the interpreting and retelling of the story occurs from one person to another. The statement announced by the last player in the Telephone Game usually differs greatly from the initial message. This is because of listening and transferring errors, translation and comprehension issues, and poor communication from which inferences and assumptions are added and details are misrepresented or omitted. All of this misinterpretation and misunderstanding stems from the challenge of communicating effectively.

Interestingly, these are all problems that occur when players in this game are in the same room or physical space. Now imagine this game getting played out over a virtual space, one phone conversation or one email after another. The same challenges and issues not only occur, but they are magnified because of time lapse as messages cross time zones, cultural and language barriers due to first-language preference and culture-specific values, and other filters often used to interpret, translate, and respond.

This is only one example of the many challenges associated with managing virtual projects. However, it demonstrates a subtle but very important factor that all virtual project managers need to know. The fundamentals of managing a virtual project are the same as the fundamentals of managing a traditional project. But there are important nuances concerning how the project management fundamentals are practiced on a virtual project due to the differences that were detailed in Chapter 1. These nuances have a number of important implications when it comes to managing a virtual project and leading a virtual project team. First, they elevate some of the core project management fundamentals in importance over others. Second, how the fundamentals are practiced and the processes are used need to be modified for use in the virtual project environment. Third, simplicity is better. Finding ways to practice the project management fundamentals in the simplest manner helps to reduce virtual project complexity instead of adding to it.

Virtual Project Planning Process

One of the key differences between traditional and virtual projects discussed in Chapter 1 is the importance of purposeful integration of distributed work outcomes. Integration takes center stage during project planning as it is the responsibility of the project manager to ensure that an integrated, coherent project plan is developed despite the fact that most of the plan details and elements are first created by project team members who may be widely distributed both organizationally and geographically. Even though a virtual project team may be highly distributed, integration of work must be centralized around the project manager.

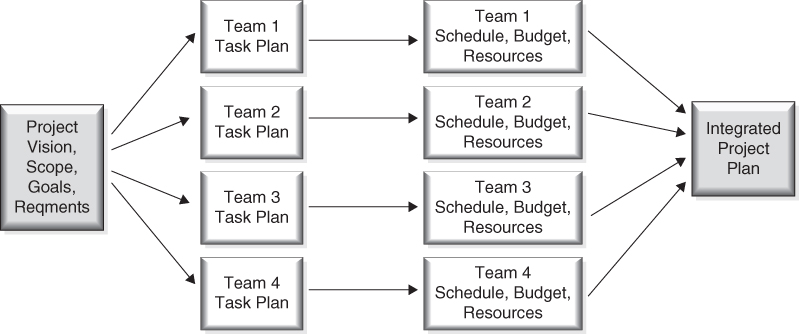

Figure 2.2 Centralized/Decentralized Project Planning Model

In Chapter 6, we discuss at length how a centralized/decentralized model is used to perform much of the work on a virtual project, but we introduce it here because the model is central to the planning process for a virtual project. Figure 2.2 provides an illustration of the centralized/decentralized planning process.

Like traditional projects, the critical information needed to plan a virtual project is first centralized and created by the project manager and his or her project planning team. This information consists of the project vision, project goals and success criteria, project scope, and the detailed project requirements. While this is the minimum information needed, experienced virtual project managers know that the following must be established to offer the greatest probability of virtual project success:

- Focus on deliverables before tasks

- Establish distributed task plans

- Integrate the project plan

- Gain project plan approval

Deliverables before Tasks

With the project scope defined and documented, the natural tendency is to move into detailed task planning. However, prior to this, many seasoned virtual project managers first go through the step of mapping project deliverables over a timeline. Co-located teams tend to manage their work by completion of tasks, whereas distributed teams more effectively (and visibly) manage their work by completion of deliverables.

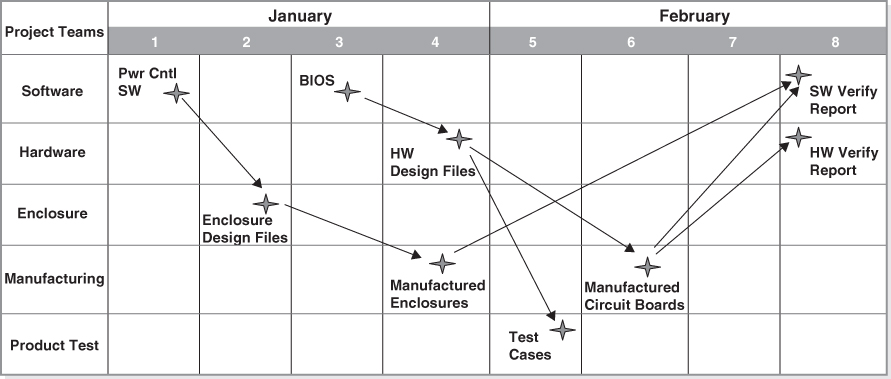

Figure 2.3 Example Partial Project Map

A process called project mapping is often used to identify the critical deliverables throughout the life cycle for each team on a project. More important, the outcome of the project mapping process, the project map, shows the cross-team interdependencies that exist between the members of the team.4 Virtual project team members are expected to act as more than just individual experts pursuing their own specific tasks; they are team members focused on tasks and the cross-team interdependencies needed to effectively deliver an integrated solution. An explicit recognition of the various mutual dependencies between the distributed members of the team is needed, especially in the virtual project environment.

Figure 2.3 illustrates a partial project map that shows the deliverables and cross-team interdependencies during a two-month period of the project. Each deliverable identified in the project work breakdown structure is displayed on the project map in the correct sequence and relative point in time. Arrows between deliverables depict the interdependencies among project members (what deliverables are needed by whom and when). The mapping of deliverables among project team members helps the team determine and fully appreciate the dependencies that exist on a project.

By following one of the deliverable chains, we can demonstrate how cross-team interdependency and collaboration is organized in this example. Pwr Cntl SW (power control software) is a deliverable generated by the software development team and delivered to the enclosure development team. The enclosure development team in turn uses the power control SW deliverable to generate its enclosure design files deliverable, which is handed to the manufacturing team. The manufacturing team uses the enclosure design files deliverable to generate its next deliverable, the manufactured enclosures, which are then delivered to the software development team, which uses the deliverable to generate its SW verify report. This mapping of deliverables shows the critical interdependencies among the software, enclosure, and manufacturing teams on the project.5

Virtual project managers should lead their teams through the creation of the project map early in the planning phase and then utilize it as a tool throughout the remainder of the project life cycle to drive collaboration, synchronization, and integration of work output across the distributed team. More on this in Chapter 4.

Distributed Task Plans

With the project-level planning information and a map of project deliverables and interdependencies in hand, detailed planning activities can be delegated and distributed to the members of the virtual team. Detailed planning is distributed to the locations where the work will be performed. Each person responsible for detailed planning will provide task plans for developing deliverables, a timeline to do so, a resource plan, budget required, base assumptions, and any identified risk in completing work and the quality of the work outputs.

To keep the work of the various detailed planners synchronized, project managers need to set clear milestone dates for detailed plan creation and establish periodic reviews to ensure work is progressing. Should any changes to project scope, requirements, or goals occur, project managers must quickly communicate the changes to the entire team so the changes can be incorporated in the detailed plan. Once the detailed plans are completed, project managers again centralize the project planning process by leading the project team through the creation of the integrated project plan.

Integrated Project Plan

The integrated plan incorporates the detailed plans of the distributed team members and presents that work as a coherent set of activities to be performed. Although the process for developing an integrated project plan differs from that used for a traditional project, the plan itself will be traditional in content. (See Table 2.1.)

Table 2.1 Project Plan Checklist

| ✓ | Project purpose |

| ✓ | Work breakdown structure / scope |

| ✓ | Project objectives |

| ✓ | Key deliverables and project output |

| ✓ | Success criteria and measurement metrics |

| ✓ | Detailed schedule |

| ✓ | Detailed budget |

| ✓ | Resource profile |

| ✓ | Risk analysis |

| ✓ | Tracking and reporting methods |

| ✓ | Communication plan |

| ✓ | Change management plan |

Project Plan Approval

As explained in Chapter 1, decision making on a virtual project can be considerably slower than on traditional projects. Decisions necessary to formally approve the integrated project plan are particularly slow to make. This is due in large part to the organizational and geographic distribution of key stakeholders who serve as project decision makers.

Virtual project managers do not have the luxury that their traditional project counterparts have of getting the decision makers together and driving to a final approval decision. Rather, multiple meetings and multiple electronic communication exchanges with multiple stakeholders will likely be required to converge on a final decision.

To help alleviate project plan approval decision delays, virtual project managers can do a number of things. First, they can ensure that there is a single approver for the project plan and that all project stakeholders are keenly aware of who that person is. Often decision delays on virtual projects are caused by lengthy debates among the various stakeholders about the identity of the decision maker. Of course, often many stakeholders believe they should own the decision rights. It is important to get clarity before a decision is needed and to document it. Once the decision maker is identified, documented, and communicated, virtual project managers can take the decision stakeholder identification process one step further and identify who will provide input to the decision maker concerning approval of the project plan. Again, many stakeholders may slow the decision process by behaving as if they have the responsibility and authority to guide the decision maker on what his or her decision should be. Some project stakeholders probably are in this position; others will not be. Virtual project managers must document who has decision input authority and make sure it is clearly communicated among the team and stakeholders.

Another cause of decision delay is the lack of necessary data for decision makers to actually make the decision to approve the project plan, or not. To speed this decision, virtual project managers should be aware of the data needed for the decision; that data collection must become a primary focus of the planning process.

Finally, virtual project managers must make sure that they, as project managers, provide a recommendation for project plan approval (or not, as the case may be) and justify their recommendation. Project managers should know as much about the viability of the project and the likelihood of project execution success as anyone else in the organization at the time of project plan approval. Virtual project managers should respectfully state their opinion, and provide justification as needed, to their senior management.

Scope, schedule, cost, and quality serve as the foundational underpinnings of success on any project, traditional or virtual. The fundamental practices and processes for establishing the project scope, developing a realistic project schedule, creating the project budget, and documenting the quality requirements during the planning stage of a virtual project are identical to those used for traditional projects. However, three challenges emerge during project execution that requires special attention outside of creating the integrated plan during project planning. These challenges are:

- It is more difficult to maintain alignment between project outcomes and business strategy on a virtual project and to maintain alignment among project stakeholders who are commonly geographically distributed.

- The virtual project structure cannot form organically as is the case for many traditional project teams. Rather, it has to be purposefully architected.

- Virtual projects are more complex. Complexities must be made visible and associated risks identified to simplify the complexity of virtual projects.

These challenges are due primarily to the physical distribution of stakeholders and the project team. How virtual project managers can mitigate each of these challenges during the planning stage of the project is discussed in the sections that follow.

Establishing Project Alignment

Even with an integrated project plan in place that has been approved and communicated, the distributed nature of the virtual project environment applies a constant force that can fragment the plan during project execution and cause major misalignment. This misalignment occurs among project team members, between the project team and stakeholders, and between what the project ultimately delivers and the anticipated business goals. To battle these forces, paying special attention to the establishment of project alignment is a critical virtual project planning practice.

Alignment is often defined as a straight-line arrangement of things or as an alliance among people. When thinking about alignment relative to individual work, it means each person (on the team) can understand their work and its meaning relative to the whole of what is being created by the team as well as the importance of their collective work in achieving the business goals of the specific project and enterprise strategy.

Alignment does not happen by chance. Rather, alignment is created (and sustained) by intentional influence. That means it is planned. Purposeful alignment is necessary on virtual projects, especially on projects that have little or no co-location among team members. The primary reason for this is that team members have limited opportunities to engage in informal discussions about why they are doing a particular project and to see how the work of each individual is integrated to the larger, whole solution. For these reasons, alignment has to be specifically and intentionally planned, documented, and communicated in ways that are clear and will be remembered.

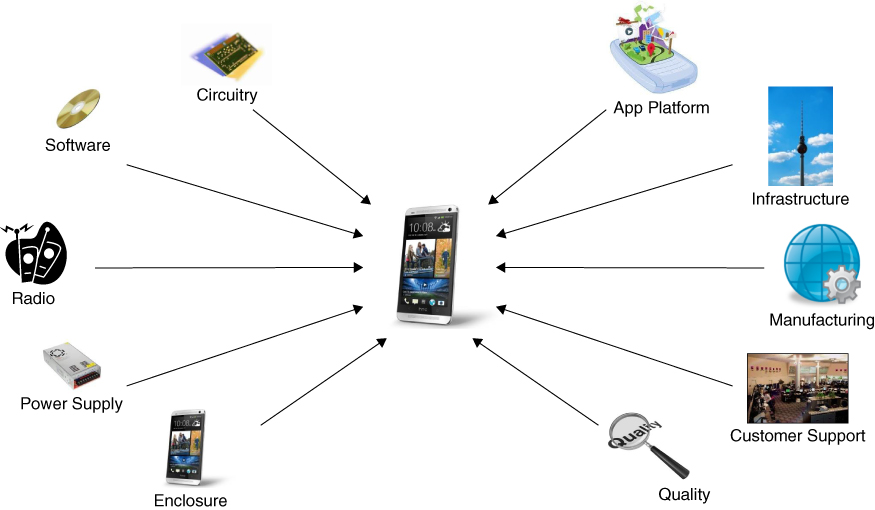

Figure 2.4 Example Whole Solution Diagram

To ensure alignment between a firm's strategy and its execution outcome, the senior leaders of an organization, the project managers, and various project team members must share a common understanding of what the project has been commissioned to achieve, what will be delivered as the project outcome, and how the outcome will be developed. Unlike traditional projects, where the critical players have direct access to one another, developing this common alignment of thinking is more difficult on a virtual project. To overcome the barrier created by distributed organizational stakeholders, project managers must work diligently in the early stages of a project to align team members to the solution to be created, with an understanding of how their efforts will contribute to the whole solution. Doing so creates a common project vision. Alignment also involves ensuring that the project supports the accomplishment of the underlying business goals and strategies. Finally, project alignment involves defining team success and the ground rules of how the team will collaborate and self-govern.

Aligning to the Vision

All project teams need a vision of what is being developed through the labor of the collective team's work. The reason for this is rather simple. It is best to have a vision of the final outcome as you work on individual parts of the whole. It is for this reason that architects build small-scale models of an envisioned skyscraper. For similar reasons, auto designers create sketches and manufacturers build prototypes. If you cannot see the whole, it is difficult to understand the value of individual parts.

In The Fifth Discipline, the seminal book on systems thinking, Peter Senge details the need to see the “whole” of things.6 He mentions that one of the greatest challenges individuals and teams face is the inability to see the whole of our work and the impact from that work. It is for these reasons that when we are working with project teams to establish a common vision, we use the term whole solution to describe the final outcome—the product, service, infrastructure solution, or other capability that the team will create and introduce into the market or organization (see the box titled “Understanding the Whole Solution Concept”). Figure 2.4 illustrates a simple example of a whole solution.

In this example, the development of a smartphone, the whole solution consists of all of the elements necessary to create the total solution for the customers of the company. Obviously, it consists of the various hardware, software, and wireless communication elements of the physical product, but it also consists of ancillary elements, such as packaging, manufacturing, infrastructure enablement, marketing, and customer support. If any one of the primary elements of the whole solution is missing, the product would fail to meet customer needs.

In a virtual team environment, the development of the elements most likely would be distributed to various team members and partner organizations, potentially across the globe. By creating and communicating the whole solution, each member of the virtual project team begins to see the holistic view of what the team is creating and how their work output contributes to the project mission and vision.

When completed effectively, the whole solution shows that success cannot be fulfilled by any one specialist or set of specialists on the team. Rather, success comes when meeting customer expectations is a shared responsibility among the members of the project teams, with their work tightly interwoven and driven toward the integrated solution even though project members are distributed across geographic boundaries.7

It can be argued that there is no point in the project life cycle more important to see the whole solution than in the initiating and planning phases of project work. This is a formidable time for project team members and key stakeholders because, on one hand, the project (really) hasn't started yet since full funding to execute has not occurred; but on the other hand, this is the time the team is being formed, expectations are being set, and perceptions of individual and collective work are being established. We have all heard the phrases “Get off to a fast start,” “Plan for early wins,” and “Build early momentum.” The value of a fast start, in reality, is more than just momentum. It also includes structure, buy-in, purpose, and meaning, all of which come from alignment of people to goals. This alignment is achieved when project managers can establish purpose and meaning of work with connection between members of the virtual team relative to the whole solution.

Aligning to Business Goals and Strategy

To provide the greatest value to a company, there must be direct alignment between the outcome of a project and achievement of one or more business goals of the company. Experienced project managers know that there is a direct correlation between project duration and alignment risk. The longer the project's timeline, the more inherent risk there is that alignment to strategy and goals may shift as the project team attempts to accommodate changes in markets served, product requirements, competitor actions, or customer demands. This is why it is so important to clearly align the strategy and goals among senior leaders, the project team, and other stakeholders during project planning. The project business case is a critical tool used to help establish and sustain alignment throughout the project (see the box titled “The Project Business Case”). To be effective in setting alignment for a virtual project, the business case must spell out the business benefits and the rationale as to why the proposed outcome is desired by customers, users, and the organization. This information is critical for all projects but is essential for virtual projects. It answers the question, “Why are we doing the project?” that creeps into the thinking of most team members (and many stakeholders) at one time or another. For team members who work in remote locations and cannot engage in informal discussions about the underlying reason and purpose of their project, the business case is their foundation for remaining aligned to the rest of the team and the organization as a whole.

Experienced project managers know that the business case is the culmination of information gathered in the initiating phase of the project and is used to establish validity and the means by which the project will prove to be a successful investment in the enterprise portfolio. The business case includes a problem statement and outlines the business value by way of opportunity analysis. This analysis assists in determining the proper fit of the project under consideration relative to other projects based on funding available, strategy, market positioning, and risk. Furthermore, a feasibility portion of the business case summarizes the financial net benefit to the organization if the project is approved. Table 2.2 describes the elements of the project business case.10

Table 2.2 Minimum Elements of a Project Business Case

| Business Case Element | Description |

| Purpose | A succinct statement of the business benefits driving the need for the project investment. |

| Value proposition | A succinct statement characterizing the value to be delivered (quantified when possible). |

| Benefits identification | A comprehensive list of the important benefits to be derived by completion of the project. The result of this effort is what the Project Management Institute refers to as the Benefits Realization Plan.11 |

| Risk analysis | A comprehensive analysis of the critical risks to the project and the planned mitigation efforts to address each risk. |

| Business success factors | The set of quantifiable measures that describe business success for the project. |

| Governance model | The project's oversight team and process for monitoring project progress. |

| Detailed cost analysis | The investment cost of the project and timing of the costs. |

| Critical assumptions | The events and circumstances that are expected to occur for successful realization of the objectives. |

| Project timeline | A project schedule identifying the critical milestones, decision points, and timing expectations by senior management and other key stakeholders. |

Aligning the Team

All project charters should provide information about the expected result from the execution of the project. The best project managers know that the project charter needs to balance high-level strategy with lower-level detail.

At the strategy level, the charter needs to describe how the project team will achieve business goals and deliver value. The charter establishes this by defining the project objectives and the capability outcome from the project (the new product, service, infrastructure, or other capability that will result because of the project outcome). Importantly, in the charter, the project objectives must align to the business strategies of the organization and provide the guiding principles that help the project manager and other key decision makers understand the scope of the project and determine resource requirements necessary for the project's success. To be effective, objectives should be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time bound.12

Project Charter

There are a lot of commonalities between project charters and project scope documents. The factor that is different is detail. The charter is often used as a decision making tool, whereas the scope document is used as a planning tool. Therefore, the charter often includes less detail because it is used to present to executive teams. The scope document is more detailed and used by the core project team to plan project work.

Team Charter

In addition to a project charter, many virtual project managers also create a team charter during project planning activities. The team charter can be appended to the project charter or be a separate and stand-alone document for the project team's use.

Table 2.3 Key Elements of a Team Charter

| Team Charter Element | Description |

| Team name | Just like products have names, teams should have a name. Names unify team participants. |

| Team goal | It's best to have the team define its goal. The project charter and scope document will detail a goal, but the purpose here is to have the team collectively describe it, write it in a (short) narrative form, and illustrate it if possible. |

| Team success metrics | Project and business metrics will be outlined in the project charter and scope document, but they may not include specific team success metrics. Team success metrics provide the team an opportunity to detail how each person will define success relative to another. |

| Conflict resolution | Understanding how team conflict will be resolved is important. It is even more important to acknowledge that conflict likely will happen. Spending time ahead of any conflict discussing how to resolve conflict is much better than doing so at the time of the first conflict. |

| Unconscious bias | Virtual team members often have biases based on myth and personal assumptions. This is especially true across cultural barriers. Spending time to demystify myths breaks down barriers and speeds the norming phase of teams. |

| Value statement | Teams can accomplish more than any individual alone. With the preceding items detailed, the team can detail a value statement. The best team value statements contain the contribution expectation of each individual and the team at large. This statement is a pledge or commitment to one another. |

| Team check-ins | Like detailing a process for conflict resolution, it is good to chart out a timeline to check on the health of the team before getting far into project execution. The checkpoints should be both one-on-one with the team member and project manager and in group form. |

As noted, one of the most common challenges for project managers responsible for a virtual team is alignment. Most project managers responsible for traditional projects follow advice from PMI in their Project Management Body of Knowledge publication and, in doing so, miss this important nuance. Although the project managers clearly detail the project's charter, they miss the intentional beginnings of creating a team charter.

Ideally, it is created in a group setting, in realtime, and details direction and boundaries, processes and protocols to resolve conflict, and expectations and practices that govern individual work in a way that, over time, builds trust, respect, and rapport. You can think of the team charter as a governance-type tool that details how work will get done among the project team. It identifies ground rules, expectations, and values. Table 2.3 highlights the key elements of a team charter.

The team charter is a critical tool for virtual project teams. Further, the team charter helps to detail elements of a highly effective team; it essentially is a plan on how to get the virtual project team right. Keith Ferrazzi identified four absolutes when it comes to highly effective virtual teams (see the box titled “Planning For The Right Virtual Team”).

Architecting the Virtual Project

Because work on a virtual project can be highly distributed, the project itself cannot form organically in the same manner as traditional projects. Instead, it has to be purposefully architected and structured to ensure all work is defined and distributed systematically and intelligently.

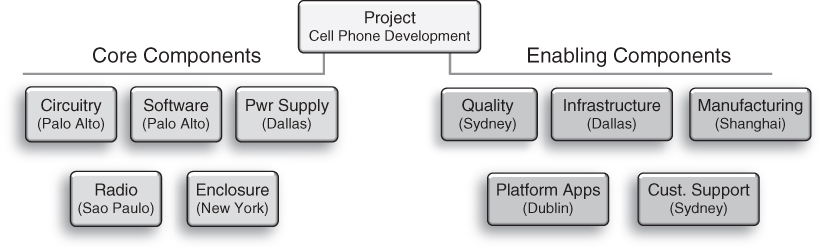

Figure 2.5 Example Project Architecture

The term architecture refers to the conceptual structure and logical organization of a system. It includes the elements of the system and the relationships between them.14 A project architecture is therefore the conceptual structure and logical organization of the project. It is comprised of core project components as well as the noncore functional components required to create and deliver the whole solution.

To create an effective project architecture, it is helpful to again take a systems approach. In any case where a new capability will be created, the project serves as the delivery mechanism for that capability and should be designed and structured in a systematic fashion. The whole solution will dictate the primary project components and enabling components needed for the project architecture.15 Take, for example, the simplified whole solution diagram for the creation of a new capability such as a smartphone as illustrated in Figure 2.4. The architecture is easily derived directly from the whole solution.

Figure 2.5 demonstrates how the architecture might be designed for the smartphone described previously.

When project teams are complex, as is the case most of the time and as illustrated in Figure 2.5, seeing the team in an architectural diagram can create better, more intentionally designed, and methodically distributed work geographically. It enables the team to see their workgroup relative to others on the team. Additionally, and importantly, seeing the architecture illustrated reinforces the fact that a virtual project cannot form organically. The software and circuitry teams may be able to come together naturally in Palo Alto, but they would not come together naturally with the power supply team in Dallas or the radio team in Sal Paulo. Further, there is no way that the manufacturing team in Shanghai will organically communicate key product attributes to the customer support team in Sydney. Again, the figure illustrates the intentionality needed to form the project team and carry out project work. If the project team cannot see their work and the work of others, the virtual project manager must illustrate the work so that it can be understood.

Understanding the Complexity of Virtual Projects

All projects have complexity. Designs have become more complex as features and integrated capabilities increase; the process to develop and manufacture the solutions requires more partners, suppliers, and others throughout the value chain; the ability to integrate multiple technologies with end user wants requires not only accuracy regarding requirements delivery but also speed and agility to change; and the current global, highly distributed business environment requires work to occur in multiple sites across multiple time zones. (See the box titled “Managing across Time Zones.”) Therefore, the ability to characterize and profile the degree of complexity associated with a virtual project has become essential for both executive leaders and their project managers.

Historically, the most effective approach for developing distributed solutions amid complexity has been to employ systems engineering techniques. A system is defined as a combination of parts that function as an integrated whole.17

Wayne Cascio is a distinguished professor and the Robert H. Reynolds Chair in Global Leadership at the University of Colorado, Denver. His research has identified a number of disadvantages virtual teams face, including the lack of physical interaction, loss of face-to-face synergies, lack of trust, greater concern with predictability and reliability, and lack of social interaction.16 Each of these disadvantages creates a nuanced challenge for virtual project managers. When aggregated, they create significant complexity.

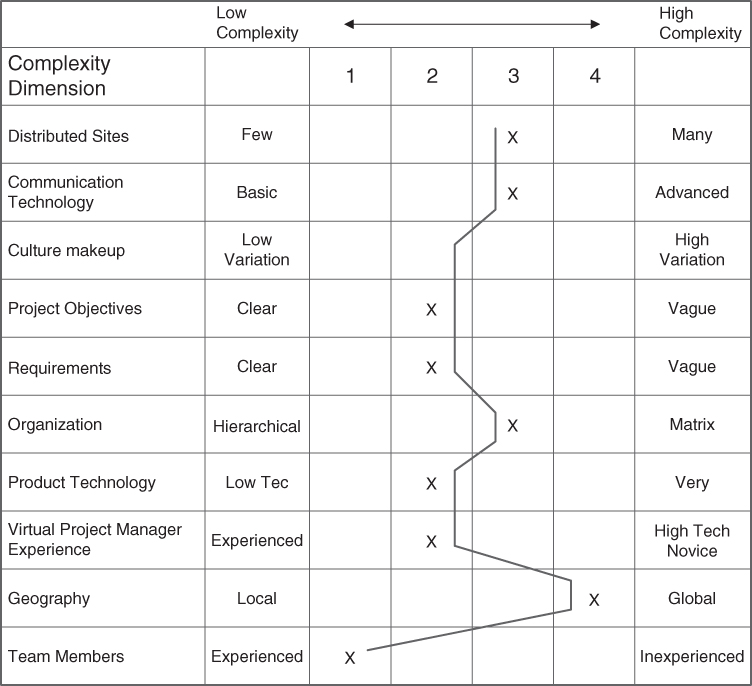

Figure 2.6 Example Virtual Project Complexity Assessment

The information project managers gain from utilizing a project complexity assessment aids in the determination of the skill set and experience level required of the project team. Further, the use of a complexity assessment also helps to guide the implementation of key project processes, such as change management, risk management, and contingency reserve determination; and helps them adapt their management style to the level of complexity of the project.

The project complexity assessment features several parts. The tool includes various dimensions (first part) as defined by a business. Each dimension of complexity is assessed on an anchor scale (second part), and when the complexity scores of each dimension are connected, a line called the complexity profile (third part) is obtained. The complexity profile is a graphical representation of a project's multifaceted complexity.18 An example of a project complexity assessment is illustrated in Figure 2.6.

Every industry has unique characteristics, every business within an industry is unique, and every project within a business is unique. This means that a firm has to customize the complexity assessment tool for its use. Project managers often start this work by determining the complexity dimensions that are specific to the organization. For example, technical complexity may be related directly to the technical aspect of the product, service, or other capability under development. Structural complexity also has a number of subfactors that involve the organizational elements of a firm. Business complexity involves the business environment in which the firm operates. (See the box titled “Defining Complexity.”)

With the dimensions of complexity identified and deemed appropriate for a particular organization and project, the next step in developing a complexity assessment is to define how each dimension of complexity will be measured. This is done by choosing a scale for each dimension.

Alternatives for the scales abound. In the example shown in Figure 2.6, complexity for each dimension is measured on a simple four-level scale (1 is the lowest complexity, 4 is the highest complexity).

Once the complexity dimensions are identified, each dimension is then assessed based on the scale established. For example, in Figure 2.6, cultural make-up of the team is assessed as a Level 2 complexity (medium variation). Once all complexity dimensions are assessed, the obtained scores for each dimension are connected to produce the complexity profile, which helps to visually depict the overall project complexity. The profile in the figure, for instance, indicates that the project is of medium complexity, with all dimensions at Levels 2 and 3, except team members who are experienced (the least complex) and a globally distributed team (the most complex).

Complexity of Virtual Interdependencies

Much of the added complexity of a virtual project is associated with the distribution of work and the web of virtual interdependencies that have to be managed. All projects have interdependencies of work and deliverables. But, for virtual projects, the interdependencies require hand-offs that are distributed geographically and among people who may have little to no personal or professional relationship with one another. This simple fact creates increased complexity of work and therefore increased risk to the project. The best solution to managing such complexity is more frequent collaboration. More specifically, best-practicing virtual project managers know to link collaboration exercises with collaboration practices. They do this by facilitating team development with intentional project planning that necessitates hand-offs more frequently, which in turn necessitates collaboration.

For an example, envision a systems develop project, scoped to take 12 months based on requirements gathering that takes two months, design and wire framing that takes three months, development that takes four months, and quality assurance and testing that takes two months, and a pilot program that takes another month. Also, consider that each function has personnel resources in different locations. As a project manager, you have options and decisions to make regarding the workflow and collaboration of the team. Those managers using best practices won't have business analysts documenting requirements for seven weeks and then hand off those requirements to the design team in week 8. Rather, managers would drive the business analysts to lead more frequent updates, discussions, and collaboration with designers, developers, and the quality assurance and test team. The likely schedule would be once every two weeks. That is the difference between a single hand-off and having multiple points of connection and collaboration.

Similar points of collaboration would be intentionally designed into the project schedule throughout the project's life cycle. Additionally, during these points of intentional collaboration, project managers would integrate team activities so that trust, respect, and rapport are being developed in pace with the project schedule itself. As one virtual project manager explained it: “Rather than focusing solely on the output associated with any single project function, the leader of a distributed project team must focus on creating more touchpoints for the team to come together virtually. Doing this creates more opportunities for providers and recipients of project hand-offs to communicate expectations, which mitigates risk of any hand-off.”

With Complexity Comes Risk

There is a relationship between complexity and risk. Virtual projects are inherently more risky than traditional projects. Any of the factors that show up as high complexity in the complexity assessment add risk to a project. The only way to truly understand the risk of any project is to conduct a risk assessment of each project item or variable and determine if mitigation or avoidance actions need to be initiated when a project is initiated and planned.

Project risk is the potential failure to deliver the benefits promised. By understanding and containing project risk, project managers are able to manage in a proactive manner. Without good risk management practices and tools, managers will be forced into crisis management as problem after problem will present itself, forcing teams to react to the problem of the day (or hour). As one well-known author stated, “If you don't actively attack the risks, the risks will actively attack you.”20 Risk management is a preventative practice that allows project managers to identify potential problems before they occur and put corrective action in place to avoid or lessen the impact of the risk. Ultimately, this behavior allows the project team to accelerate through the project cycle at a much faster pace. Identifying risk on a virtual project can be especially challenging as explained in the box titled “Virtual Project Risk: Identifying Silent Killers.”

Understanding the level of risk associated with a project is crucial to project managers for several reasons. First, by knowing the level of risk associated with a project, project managers will have an understanding of the amount of schedule and budget reserve (risk reserve) needed to protect the project from uncertainty. Second, risk management is a focusing mechanism that provides guidance as to where critical project resources are needed—the highest-risk events require adequate resources to avoid or mitigate them. Finally, good risk management practices enable informed risk-based decision making. Having knowledge of the potential downside or risk of a particular decision, as well as the facts driving the decision, improves the decision process by allowing project managers and teams to weigh potential alternatives, or trade-offs, to optimize the reward-risk ratio.21

The risk assessment and management plan is more than a simple risk register. Importantly, it is a probability tool and response plan. In order for it to work as such, all known and potential risks must be documented, explained by way of project and business implication if realized, ranked in terms of probability, and associated with leading indicators of occurrence to allow as much time as possible to enact a detailed (step-by-step) response plan. Collectively, that is the risk management plan, and it usually is associated with the planning phase of projects. However, for virtual projects, risk management needs to start in the initiating phase. This is necessary because a good (thorough and accurate) risk management plan can do more than simply illustrate the mitigation of a risk; it can save money and time for project managers and teams. It will certainly be updated and refined in the planning phase and throughout the executing phase, but it needs to start when the project is first initiated.

As can likely be imagined, planning for risk can be much more time consuming for virtual project teams than for co-located teams. When it comes to risk planning, the entire team should be involved. That can occur as a brainstorming session for co-located teams. For virtual teams, project managers often start by emailing each team member, requesting an email returned that contains perceived risks, triggers, impact, and probability of each occurring throughout the project's life cycle. Once the responses are received, virtual project managers aggregate the risks, categorize the risks, and schedules a virtual meeting (or more meetings, as the case may be). In this meeting, it is best if the whole team is involved, but due to geographic distribution, this may not be possible. If it is not possible, project managers will need to conduct multiple meetings.

During the risk management planning meeting, project managers need to be very deliberate with time management as well as the technology used for the meeting. Likely, the technology will be teleconference or video conference. It is best if all participants could have a shared screen so that they can keep pace with the team leader as the team works through each risk. If the project team is distributed as much as illustrated in Figure 2.5, this approach to risk management is the only option project managers have to capture and plan for project risk. In this case, virtual project managers conduct all the same work as co-located project managers, but managing virtual risk is much more difficult and much more time consuming, and require much more planning.

Planning Virtual Communication

The 1967 movie Cool Hand Luke made this statement famous: “What we've got here is a failure to communicate!” This statement can very well apply to many virtual projects. A documented communication plan is valuable for any project but is essential for virtual projects because of the distributed nature of the team and heavy reliance on technologies to communicate.

Successful projects involve a significant amount of communication among team members. For example, project managers need their management stakeholders to understand project issues. Management needs to understand how a project is progressing and how the team is performing according to its goals and mission. Virtual team members need inputs and information from other team members and reciprocally must provide their inputs on project tasks and issues. Project documentation must be reviewed, discussed, and approved to ensure the project will succeed. To ensure that this level of communication is happening on a virtual project, the virtual team should create a communication plan early in the planning process to solidify their agreement on how information will be communicated among team members and to stakeholders throughout a project.

Communication Items to Be Addressed

A communications plan includes the rules and guidelines by which a virtual project team will manage communications during the life of the project. It is used to help team members think through what kind of communication mechanisms they will need, it helps establish expectations of proactive communication between team members, and it establishes what the team agrees to do. Specific items that need to be addressed in a communication plan include these:

- How status reporting will be performed and who is responsible

- What team meetings will be established and who participates

- What project reviews will be required and who participates

- Who talks to whom and how often

- How documents will be exchanged

- How decisions will be documented and distributed

- What communication technologies will be used

Since project managers and their team members spend much of their time communicating and interacting with one another, a good communication plan that addresses the listed items establishes a framework for effective and efficient communication on the project.

Elements of the Communication Plan

A comprehensive communication plan should include the what, how, and when various forms of team communication and collaboration need to happen. It specifies how the communication between team members and with project stakeholders will be satisfied. Seven key elements of a communications plan are listed next.22

- Electronic technology is the primary communication medium for the virtual team. The team should evaluate and select the most appropriate communication tools available to the organization. Proper training in the applied use of the tools is critically important and must be provided for each participating project location.

- Principles and guidelines for leading and managing team meetings should be defined. Use good basic meeting management techniques that encourage engagement and frequent team member interaction.

- Identify all expectations by senior management that lay the foundation with project team members for open communication of information. This will facilitate the flow of project information and issues.

- Clearly identify the team members responsible for gathering, providing, and distributing specific project information to the project manager, with the appropriate format and frequency expected.

- An approved management escalation process and set of procedures is provided for the communication of issues, barriers, and other problems. This process facilitates flow of information to senior managers when higher levels of management attention is needed.

- Include ground rules for communication of project information such as the use of email, subteam communications, and decisions that are made during information meetings. This ensures that team members have the right access to this informal communication. There should also be appropriate guidelines set for expected maximum response time to emails and voice mails, which can have significant impact on productivity across the project team.

- If it pertains to a project, the communication plan should also provide the structure for communication to and from outside partners and customers. If the project team involves contractors or outside partners, the plan should also define how they will be involved in team meetings, project monitoring, status reporting, and project reviews.

Using the Communication Plan

Often the communication plan is but one component of the overall project plan. Because of the criticality of effective communication on a virtual project, however, we recommend that the communication plan be a stand-alone document. This will ensure extra focus to increase the probability that the plan contents are put into practice.

On a virtual project, the amount of communication that takes place among team members and with project stakeholders will vary depending on a number of factors, as will the mix of both formal and informal communication exchanges. The two most significant factors that influence the amount of communication are team size and project complexity (where complexity is again defined as the number of virtual interdependencies between team members). General guidelines for ensuring the communication plan is effective are listed next.23

- Identify all stakeholders who need to be involved in project communication. (See Chapter 4.) This will include team members, middle and upper management, external governing bodies, and outside customers, clients, subcontractors, and partners.

- Select the team communication tools carefully through the development of a technology strategy. (See Chapter 8.) Communication tools should enable the effective use of the plan, not inhibit it.

- Decide how often the team needs to communicate and if the communications need to be formal or informal. Along with this, for formal communications, decide which communications should take place in larger cross-team meetings and which communications need their own forum.

- Ensure that only the people needed for a particular type of communication are involved. Often, too many people are involved either by invitation by project managers or by self-invitation. This situation adds risk that miscommunications or misinterpretations will occur. Restrict participation to the critical players needed for an exchange.

The lack of physical presence is one of the major challenges for virtual project teams. Limited physical presence is most commonly thought of as limited face-to-face interaction among team members and with project stakeholders. However, physical presence also includes limited access to critical project information that is needed to ensure that distributed team members view themselves as a cohesive team with a common mission, goals, and plan to go execute. Use of an effective communication plan can assist in overcoming this limitation.

Project planning for a virtual team must be focused on establishing visual representations of what needs to be accomplished, how the team will interact during project execution, and how alignment with to the organization's goals and strategies will be maintained. This planning work, and its associated project plans and deliverables, is vitally important as it creates the foundation and potential for the team to become high performing. Building a high-performing team is the focus of the next chapter.

Assessing Virtual Project Planning

As they navigate virtual projects through the planning phase, project managers must be cognizant of key success factors. Such factors can be discerned from the business case and scope document, among others. The Virtual Project Planning Assessment measures project readiness to move from planning work to executing work. This is, obviously, a very important part of any project since many people perceive the project as actually starting when project execution begins. This assessment can be used as a barometer or benchmark to validate all project plans for adequacy and readiness for project execution.

To perform the assessment, virtual project managers and others on the project team should complete the assessment tool. Once it is complete, they come together to discuss responses to each item and to mitigate any “no” response that may prevent the team from achieving project outcomes.

As can be seen, when each of the items in this assessment is answered “yes,” the organization (specifically the project manager managing the project and the stakeholders impacted by it) are more apt to be “ready” than not. Whenever there is a “no” response, it warrants further discussion to determine why and is a prompt to further detail project plans or steps to put into place to move the “no” to a “yes” response.

Virtual Project Planning Assessment

Project Name: _______________________________

Date of Assessment: ___________________________

Assessment Completed by: _____________________

| Assessment Item | Yes or No | Notes for All No Responses |

| Project Setup | ||

| The project mission and vision are documented. | ||

| Project goals and objectives are defined and documented. | ||

| The project statement of work and scope are clear and documented. | ||

| The project success factors and key performance indicators are defined and documented. | ||

| The project requirements are clear and documented. | ||

| The project business case has been approved. | ||

| The project charter has been documented. | ||

| A project complexity assessment has been performed. | ||

| Project Team | ||

| The project architecture has been documented. | ||

| All distributed team sites have been identified. | ||

| All external partners have been identified and are participating in the project planning as required. | ||

| The project team charter has been documented. | ||

| The project mission, vision, and goals have been communicated to and reviewed by all project team members. | ||

| All tasks have been adequately distributed to the various team sites. | ||

| The experience level of the team is consistent with the complexity level of the project. | ||

| A cultural complexity assessment has been completed. | ||

| There is a high level of change acceptance (low level of change resistance) in the organization. | ||

| There is a high level of leader credibility (of sponsor and project manager) in the organization. | ||

| The organizational decision making process is participative and collective. | ||

| Project Plan | ||

| The project deliverables and key milestones have been mapped. | ||

| Each distributed project team member has completed their task plan. | ||

| Each distributed team member has a baseline schedule. | ||

| Each distributed team member has an estimated budget. | ||

| Each distributed team has a resource plan and commitment for resources from functional managers. | ||

| The integrated project plan is complete. | ||

| The integrated project plan supports attainment of the project goals. | ||

| The integrated project plan has been approved and organizational commitment has been received. | ||

| Technology | ||

| A technology strategy has been completed for the project. | ||

| Virtual communication and collaboration tools have been selected. | ||

| Local infrastructures at the project teams' sites will support data performance requirements for the selected technologies. | ||

| Virtual communication and collaboration tools have been implemented. | ||

| All team members have access to the communication and collaboration technology platforms. | ||

| All team members have been trained on use of the technology. | ||

| Execution Strategy | ||

| The project and expected outcomes have been considered and discussed as a priority for the organization. | ||

| The virtual project is planned to integrate cross-team collaboration and allow for and celebrate short-term wins. | ||

| There is a mature method for managing the project and leading a geographically distributed team. | ||

| The communication plan is detailed and appropriate relative to the project complexity. | ||

| The virtual project team understands and has approved the communication plan. | ||

| The communication plan clearly details an escalation process for conflict management and decision making. | ||

| Findings, Key Thoughts, and Recommendations | ||