CHAPTER 6

EMPOWERING THE PROJECT NETWORK

“I had to learn to let go.” That is how Jeremy Bouchard describes one of the major personal transformations he had to experience to become a better manager of virtual projects. What Bouchard is referring to is the sharing of tasking, problem-solving, and decision-making power between the project manager and team members who are geographically and organizationally distributed. However, this is only half of what we call the duality of the virtual project manager's role. The other half is the need to provide strong centralized leadership, particularly during the forming and storming stages of team development (as described in Chapter 4). This centralized/decentralized duality of the project manager's role is in effect on all projects, traditional and virtual, but it is amplified considerably on virtual projects due to the lack of face-to-face interaction and social presence caused by geographic distribution of the project team. Also, the duality of the role brings to light many of the challenges associated with managing a virtual project that were discussed in Chapter 1.

As Jeremy Bouchard experienced directly, one of the most challenging and confusing aspects of managing a virtual project is knowing when to pull the reins in to assert more centralized and direct control and when to let the reins loose to allow more empowerment of the team. That challenge is the subject of this chapter.

Centralize First

As explained in Chapter 1, one of the primary differences between traditional projects and virtual projects is that virtual projects are established on a series of networks (organizational, technological, and human), not on physical location and direct interaction. The lack of physical interaction becomes a constraining factor in the creation of human networks on virtual projects. It falls on project managers to facilitate the creation of most virtual connections when a project is in the early stages of initiating and planning. To establish core elements of the project networks, project managers must pull in and facilitate early communication, collaboration, and personal interaction.

Networked Projects

The concept of the networked enterprise emerged in the 1990s with the realization that hierarchical bureaucracies were being replaced by horizontal enterprises that were enabled by the use of digital technology to connect organizational nodes.1 In networked enterprises, components (people within the organization) are both independent of and dependent on other network components where knowledge is created and retained. This dependency becomes an interdependency when the components of the business network begin sharing common goals.

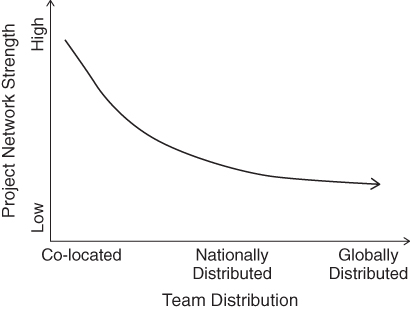

What has not been discussed in great detail is that the emergence of the networked enterprise has brought forth the creation of networked projects. Because of the proliferation of the use of digital technologies to share and create work products, nearly all projects are now networked projects that are based on a series of horizontal organizational connections. The strength of the project network is based on the strength of the relationships among project team members. For virtual projects, the strength of team member relationships is influenced by one key factor—the level of distribution of the project team members. (See Figure 6.1.)

Figure 6.1 Project Network Strength as a Function of Team Distribution

Communities and Ecosystems

A couple analogies are helpful to understand the reasons behind the variation in network strength in relation to team distribution. On traditional projects, which are largely made up of co-located team members, the sharing of physical space forms a community. Everyone sees one another on a regular basis, some people share commonality of work by participating on the same project, and some people establish personal relationships that transcend the workplace. As a result, an organizational and project community are formed. When someone new joins the organization, they become part of the community.

In contrast, members of a virtual project do not have the benefit of sharing a common community. However, members of the virtual project are highly dependent on other members of the project team for their own growth and success. Instead of being part of an organizational community, a better analogy for shared dependency on a virtual project is that of an ecosystem.

The concept of an ecosystem was first defined in 1935 by Arthur Tansley, who characterized an ecosystem as a whole system comprised of biological organisms with a complex set of networked relationships necessary for common survival.2 The biological ecosystem concept was then leveraged in the 1990s to define the concept of the business ecosystem.3 In business ecosystems, firms are not viewed as independent entities, but rather as part of a wider network of companies that both collaborate and compete to add and extract value from the industries in which they participate. One of the most obvious business ecosystems is that which was created by Apple Computer. Networked to Apple are a large number of companies and individuals in the personal computing, telecommunications, and entertainment industries that both collaborate with and compete against Apple. The result has been unprecedented growth in the industries.

Both biological and business ecosystems provide powerful metaphors for understanding a virtual project built on a series of complex networks. As in biological ecosystems, the virtual project network is a community of agents with different characteristics, specialties, and interests who are bound together by mutual relationships as a collective whole. The fate of each agent (team members) in the ecosystem is related to the fate of the others (successfully or unsuccessfully completing their part of the project). Cooperation and collaboration between members of the ecosystem is necessary for successful completion of the virtual project.

Ecosystem Keystones

Within an ecosystem (biological, business, or project), there always exist entities that are referred to as keystone members. In complex organizational networks such as virtual projects, it is crucial that these key players or hubs exist in order to establish and enhance network stability. Network stability refers to the number of direct connections between the network elements. If these human hubs do not exist in a project network, the network will remain highly fragmented. On virtual projects, project managers become the primary hub, while other functional players, such as subject matter experts, team leads, and functional managers, emerge as secondary hubs. A disproportionate number of network connections flow through and surround these keystone players.

It turns out that this structure of richly connected hubs almost always emerges as networks evolve their connections over time. In a biological ecosystem, certain species emerge that serve as hubs in food webs. In project ecosystems, project managers and other keystone members act as hubs that serve as information and communication conduits between team members. (See the box titled “Connecting New Delhi and Tel Aviv.”) The point we are making is that in networked structures such as virtual projects, strong hubs served by keystone players must exist to establish a high level of performance and to maintain system health.4 Virtual project managers must realize the critical role they play as keystone hubs on virtual projects and work diligently to help establish a large number of project network connections between team members. Referring to Figure 6.1 again, the more a project team is separated by distance and time, the more effort project managers have to concentrate on establishing communication and collaboration connections. Even though a virtual project team may be highly distributed, early communication and integration of work must be centralized around the project manager in order to strengthen the connections within the project network.

Singular Perspective

Before a networked organization such as a virtual project can establish the interdependent connections and relationships necessary to achieve its collective goals, a change in mindset must occur. People in an interconnected network first and foremost view themselves as individuals with individual talents, skills, and needs. As we explained in earlier chapters, the individualistic mindset must shift to that of a collective viewpoint where team members see themselves as a group of individuals who share a common project mission and who must collaborate as a team to achieve project goals.

This “One Team” perspective is of course a centralized concept that must be driven by project managers. On traditional projects, this singular perspective is facilitated in large part by physical presence and social interaction. People literally see themselves as part of a team, and team identity is relatively easy to establish. This is not the case on virtual projects where social interaction and physical presence are severely limited or completely nonexistent. The “One Team” perspective must be purposefully put forth by virtual project managers and consistently reinforced from the primary hub of the project network.

Communicating Common Goals

One of the most effective ways to begin establishing the “One Team” perspective is by communicating the project goals as a shared responsibility of all team members. Centralization is therefore established through a common set of goals. The project charter (see Chapter 2) is an effective vehicle for documenting the common goals of the project. Consider the following goals statement from an example project charter.5

The University is looking for new ways to help alumni stay connected to the university post-graduation. The website to be developed will 1) create the means to establish a strong alumni social network, 2) provide a portal for the university to communicate activities, information, and needs, and 3) establish a repository of academic research information for the alumni to access and contribute to. The project will be completed prior to the Fall 2019 academic semester, and cost no more than $60,000 to implement.

This simple goals statement is a very powerful mechanism for pulling a network of distributed project specialists together to achieve a common goal. What is eloquent about this goal statement is that it also contains an element of project mission:

Creating a website that will be used as a resource to help alumni stay connected to the university and with one another post-graduation.

Additionally, this goal statement contains elements of the project and team charter. Beyond the goal itself, there is an understanding of value, success metrics, and benefit realization. A simple goal statement, when articulated well, establishes the “One Team” perspective in a compelling way.

Using Trust to Strengthen the Network

In order to begin distributing responsibility and authority to various team members on a virtual project—a necessity for effective virtual work—the connections among team members must be established and be strong. Project network connections are established through communication. They are strengthened and maintained through trust among project members. Trust among team members is the brass ring that binds the project network together.

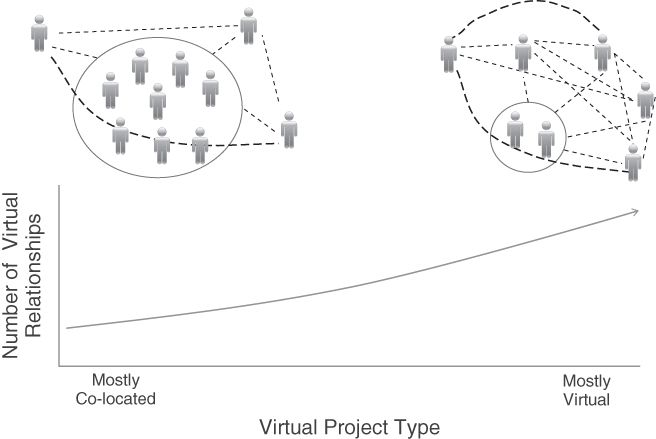

Figure 6.2 Project Type Affects the Number of Virtual Relationships

Virtual teams with high levels of trust are more effective at distributing power of decision making and problem solving and are more willing to readily share information with one another.6

As Figure 6.2 illustrates, however, the type of virtual project has a large effect on the number of virtual network connections that must be established and maintained. The higher the degree of virtualization, the greater the number of virtual connections on the project, and therefore the more tenuous the overall level of trust on the project.

Why is trust so important on a virtual project? As both authors and practitioners have observed, trust is the key ingredient necessary in preventing the geographical, organizational, and cultural distances between team members from becoming psychological distances.7 On traditional projects and even on mostly co-located virtual projects, a high degree of physical and social presence exists, thus enabling trust to be established quickly by repeated encounters and communication exchanges. As the level of virtualization increases on a project, it becomes harder to gain the trust and confidence among team members when they never meet in a physical setting. Communication becomes less personal and more transactional.

To compensate for this, initial conversations and attempts to collaborate have to be centralized and intentionally driven by virtual project managers, along with assistance from other keystone members of the project ecosystem. In many instances, virtual team members do not even know whom to connect with when they desire to engage in knowledge-sharing and task collaboration conversations. The keystone members first establish the virtual connections and, in the process, also establish a base level of trust among members of the new connection. Once trust is established, maintaining and strengthening it becomes the next challenge.

Research from Terri Kurtzberg suggests that experts believe that maintaining and growing trust on a virtual team is almost exclusively determined in terms of reliability.8 Specifically, virtual trust is based on two key aspects of reliability: reliability in communication and reliability in action. Reliability in communication refers to trusting that a response to a communication will be received from another team member when needed. Lack of response or recognition of receipt of a communication quickly diminishes trust that future communication will be responded to. Reliability in action simply means doing what you say you are going to do. Following through on commitments is the single most effective way to strengthen and maintain trust on a virtual project.

Establishing Commonality in Process and Tools

Virtual projects greatly benefit from commonality in methods, processes, and tools used to facilitate communication and collaboration among project team members and to integrate work outcomes across the projects. Projects are dependent on methods, processes, and tools for the success of work activities that produce the various project outcomes. Commonality in primary methods and processes drives consistency in work behavior and results. Commonality in methods, processes, and tools is best established through centralized discussions and decisions.

Virtual teams must begin with a process of convergence on which methods and processes will be common across the team and which technological tools will be adopted to facilitate those methods and processes. These decisions should not be mandated by project managers—a critical point that we cannot emphasize strongly enough. Look to the process of choosing common methods, processes, and tools as a way of building the team and strengthening the project network. Having open discussion and debate on the best methods, processes, and tools to employ will create buy-in on the part of team members. Mandating a standard set of methods, processes, and tools, by contrast, likely will serve to alienate some team members and potentially damage work relationships.

The goal of centralizing the design of the major methods and processes is to achieve consistency; however, they should not be designed so as to become overly constraining or negatively impact the natural ways of conducting project work. The classic example is trying to standardize the overall project processes to support either a waterfall or an agile methodology across the team. If the team is multidisciplinary, likely both methods (and others) can and should be used. Rather than trying to win the debate over the use of agile, waterfall, or another method, it makes more sense to standardize the methods and processes for synchronizing and integrating work outcomes, managing risk and change, and tracking and reporting project progress.

Centralizing the discussions enables making decisions on how much structure is required and how much commonality is needed. We recognize that each virtual project is unique, so what may have worked for one project may not work for another one. Factors to be considered are how distributed the team is (higher distribution usually requires more commonality), how multidiscipline the team is (the more disciplines involved, the less desire to standardize), how complex the project is (more complexity drives higher need for commonality), how many external regulations are imposed, and how many specific requirements are levied by project stakeholders.

The selection of technological tools that will be adopted and used by the project team to facilitate their virtual work is another matter that is best discussed in centralized conversations. As we describe in detail in Chapter 8, there is no ideal set of technologies for all virtual projects. All organizations are unique, as are their virtual projects and the capabilities of their project team members; so too are their communications, collaboration, and project management needs. Project technologies, therefore, must be selected based on how well they support the needs of the team, how they complement the culture of the organization and project, and how well they integrate with the suite of tools currently in use.

Creating Tacit Knowledge

The more a project team works together and collaborates on building the project plan, completing project tasks and deliverables, presenting information to stakeholders, and so on, the more they learn about one another as people and professionals. In particular, they learn who knows what, what needs to be done, who possesses what skills, how to best communicate with one another, and basic knowledge of how to work together as a team.9

This is known as tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge refers to the things people know how to do without having to think about it. We can all think of things in which we have developed tacit knowledge—driving an automobile, playing our favorite sport, cooking a particular meal, or setting up a conference call using our company's information technology systems. After a while, we no longer have to think about how to do these things, we just do them by rote.

Creating tacit knowledge on a team is a similar process, but is dependent on how often and to what degree team members work together. Teams naturally begin to learn whom to go to for specific tasks without purposefully having to divide the tasks.10 For example, in a closely contested game of basketball (or any sport), a team implicitly knows who the best shooters are in tense situations; therefore, players know whom to get the ball to score. Project teams have the same characteristic, and that is built on tacit knowledge. Over time, the tacit knowledge they create guides them to know whom to go to in particular circumstances and situations.

This is another area where traditional project teams have a distinct advantage over virtual teams. Tacit knowledge is created much more rapidly and broadly on traditional teams because of the higher degree of social interaction. With social interaction limited on virtual teams, developing knowledge about such things as who knows what, what tasks need to be completed, and who are the most skilled communicators takes longer. The more work and collaboration a team can perform together, especially during the early stages of a project, the quicker tacit knowledge will be created. (See the box titled “Using Team Training to Create Tacit Knowledge.”)

Nearly all authors on the subject of virtual organizations and virtual teams discuss the importance of holding face-to-face meetings with as many team members as feasible, particularly at the beginning of a virtual project. More than anything, face-to-face meetings serve to accelerate the creation of tacit knowledge between virtually distributed team members.

Power of the Initial Face-to-Face

Raphael Sangura is an educator and industry consultant who works with companies that have moved to a virtual model for developing and producing products and services. He has consistently observed something interesting within the companies that he works with. “When I discuss the importance of face-to-face contact between members of geographically distributed teams, I get unanimous agreement from senior managers, middle managers, project managers, and team members that getting the virtual project team together is critical to developing personal relationships, trust, and distributed empowerment. However, when the virtual project managers from these firms attempt to get funding and time to bring the teams together for face-to-face meetings, their requests are often denied by the same middle managers or senior managers.” When asked about this predicament, Sanguara concluded: “Either middle or senior managers don't really buy in to the importance of the face-to-face meetings, or they don't fully understand the return they will gain from their investment in money and time.”

Businesses often debate, the benefits versus the costs of bringing a geographically distributed team together. However, the best virtual organizations no longer debate this issue. For them, the act of bringing their geographically distributed teams together periodically is embedded in their project planning and execution practices.

There should be no debate within your organization, either. The benefits of team face-to-face meetings are well documented in case studies, industry research, and team member testimonials. The short list of benefits that are consistently cited include these:

- Accelerated establishment of relationships

- Increased personal bonds and trust among team members

- A clearer understanding of roles and responsibilities

- An increased commitment and accountability for meeting team deliverables and deadlines

- Broader cross-cultural awareness

- Establishment of direct lines of communication among team members

- Transfer of power from the project manager to empowered team members

When realized, these benefits move the group of individuals assigned to a virtual project to a higher degree of team performance.

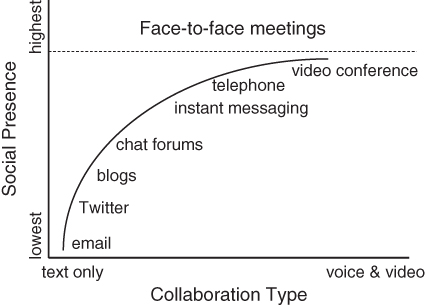

These benefits are realized in large part because of an increase in social presence on a team. Social presence is the degree to which personal connection is established among team members. The higher the level of social presence, the stronger the personal connection is between team members. Relationships, personal bonds, trust, commitment, and team empowerment all depend on strong personal connection. Face-to-face meetings have the highest degree of social presence than any of the collaboration methods and mediums used by geographically distributed teams. (See Figure 6.3.)

Figure 6.3 Degree of Social Presence by Collaboration Method

As stated previously, trust is built on personal relationships. Therefore, a team cannot establish trust if its team members do not know one another. By bringing members of a virtual team together at the beginning of a project, relationships begin to form between them and personal bonds begin to strengthen. This is due to the fact that team members begin to know one another as people with personal lives, different personalities, families, and common interests outside of work. It becomes easier to trust one another when this level of understanding about one another and personal bonds are allowed to form.

With relationships and trust beginning to be established, an increased commitment to the people on the team and to the team goals begins to form. As one virtual project team member told us, “My deadlines now no longer affect a voice on the phone or a person writing an email—they now affect my friends and colleagues. I feel that my tasks are much more important to complete because I don't want to let down people I know.” The implication of this is important for geographically distributed teams. By creating bonds between people through a face-to-face meeting, commitment and productivity increase rapidly.

Since personal ties degrade over time, best-practice virtual project managers have learned that periodic face-to-face meetings are required to maintain a high level of virtual team performance and commitment to project goals. This is an important concept to understand. Investing in an initial face-to-face meeting is good, but not nearly sufficient. Face-to-face meetings are necessary throughout projects, especially when conflicts arise, new members come on board, and project goals shift. All of these occurrences can begin to erode the personal bonds that are established in the initial face-to-face meeting.

The list of benefits of face-to-face meetings is long and powerful, and the value of such meetings is clear: If an enterprise wants to increase the performance and output of its virtual project teams, it must plan for and invest in periodic face-to-face meetings. This means that senior managers must provide the funding and time for face-to-face meetings, and virtual project managers must include face-to-face gatherings as part of their process and be able to facilitate the meetings effectively.

Empowering by Decentralizing

The reason project managers of virtual teams must take the team through the centralization activities described in the previous sections is to enable the team to accurately represent the interests of the project when they are empowered to solve problems, make decisions, and drive execution of work on behalf of the project manager at the local level. They must be connected through the project network to other team members regardless of physical location; they must identify with the team; they must know the goals of the project; they must have a base level of trust in their fellow team members; and they must have developed an understanding of their strengths and skills. With these actions in place, virtual project managers are in good positions to begin decentralizing tasking and execution of work, solving of problems, and decision making activities to team members who are closest to where work is being performed.

In today's nonhierarchical, networked organization, centralized command and control of work activities is rare and mostly ineffective. In networked organizations, ownership of work performance and completion of outcomes has to be distributed across the network. It is simply a case of form follows function—meaning that the structure of the organization influences how the work must be performed and managed. Projects, as central elements of organizations that normally mirror organizational structure, follow the same form-follows-function rule.

This means that for the networked project, project managers must delegate and grant responsibility and authority to the various team members. For virtual projects, delegation of authority becomes a risky proposition for project managers. It involves transferring an element of project leadership to another person, but to a person who is located in another geographical location, is in a different time zone, and who may have a different first language and different cultural norms. In such situations, the risk of distributed empowerment becomes higher.

To mitigate some of this risk, project managers must keep four key things in mind when delegating work virtually:

- Communicate the end result desired. In order to be successful, team members who have been delegated work must have a clear understanding of what it is they are to achieve. The overall goal, scope of work, and deadlines must be clear and discussed in detail.

- Grant authority to work autonomously. With the responsibilities communicated and granted, recipients of delegated work must also be given the authority to plan their work, solve problems encountered, and make relevant decisions. Project managers must explicitly communicate the level of authority they are granting to prevent recipients of delegated responsibility from having to guess their level of authority.

- Work, measure, and evaluate at the deliverable level. On a virtual team, project managers will not be able to manage at the task level. Team members must have the latitude to accomplish tasks and must be trusted that the tasks will be accomplished. Project managers must “up-level” management oversight to the deliverables (and likely the major milestones) level of work.

- Ensure resources accompany granted responsibility. It does no good to grant team members authority to take control of work if adequate resources are not available to perform the work. Resources include enough people, time, budget, and materials to do the job. Project managers are responsible for ensuring adequate resources are available, even if they do not personally control the resources.

This last point seems to be the most obvious factor in effective delegation of virtual work. However, it is raised most often by project team members that have been delegated additional responsibilities, as a primary reason for failing to complete the work that has been delegated. Project managers must not falsely assume that resources are going to be available to perform the work. They must continually ask those to whom they are delegating responsibility and authority if they have adequate resources to perform the work. If at any time the answer is no, project managers have the responsibility to ensure the situation is corrected, even though people within the organization who can remedy the situation directly may be halfway across the globe. If that is the case, project managers will find themselves negotiating for resources across physical, time, and possibly cultural boundaries.

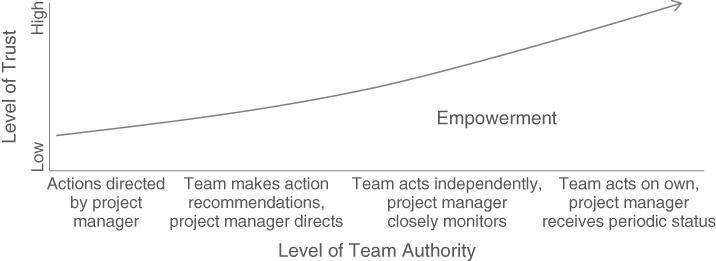

Of course, delegation of work is likely a gradual process due to the underlying factor that affects project manager willingness to delegate—trust. Trust and delegated authority are closely linked, as Figure 6.4 illustrates. The more that trust increases on the part of project managers, the more likely they will be to allow team members to work independently.

Figure 6.4 Trust and Delegated Authority Relationship

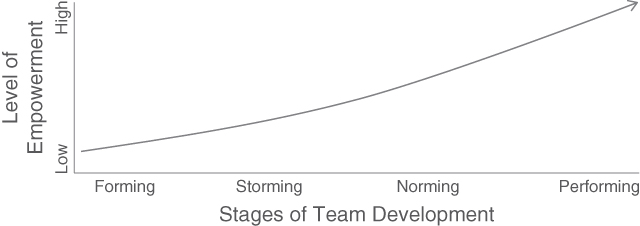

Figure 6.5 Increasing Empowerment as Team Development Progresses

Team Empowerment

In the world of networked organizations and distributed teams, the word empowerment is used frequently. Because of this, we seldom, if ever, stop to consider what it means. Power, in the context of the project environment, is the ability to effect change and influence others and having the authority to get things done.12 Empowerment, then, is the act of one person sharing power with another person. It is granting another person the authority to effect change, make decisions, solve problems, set goals, and task others on behalf of someone else—in our case, the virtual project manager.

Empowerment is the fundamental factor that makes decentralization possible on a virtual project. As team members are granted greater power, they will begin to act more on their own and rely less on the project manager's direction. They will take on greater responsibility for their work, become more comfortable with making decisions and solving problems at the local level, begin to act proactively instead of reactively to changing project conditions, and ultimately become more motivated to succeed. In their book titled The Power of Product Platforms, Marc Meyer and Alvin Lehnard recognize that “there is no organizational sin more demoralizing to teams than lack of empowerment.”13 This is especially true on virtual projects, which consist of distributed team members who must work independently much of the time.

Sharing of Power Takes Time

Empowerment does not, and should not, occur all at once. The release of power from project managers to virtually distributed team members must occur gradually and over time. Remember the primary theme of this chapter: Virtual projects have to be centralized first to establish commonality, then decentralization can occur over time as the team matures and trust builds. Figure 6.5 conceptually illustrates the progression of empowerment as a team moves through the various stages of the Tuckman team development model.

Why the gradual release of power? The release of power is dependent on the amount of trust and confidence that project managers have that their interests—the goals of the project team—will be adequately represented by others with whom they share their power. As we know, trust builds over time. Therefore, the sharing of power will occur over time. Even though the granting of empowerment over time can be frustrating to some team members, consider what often happens to people who have had little to no power and then suddenly find themselves in positions of influence. Many times they overcompensate, overuse their power, and get into trouble, particularly when it comes to making decisions. Other times, they simply run from their newfound power, fearing to exert their authority and influence because of the fear of making mistakes. The gradual granting of empowerment helps to ensure people are comfortable assuming authority and that they use their new power to further the interests of the project. However, project managers cannot put off granting empowerment for too long. When a project enters the execution stage, the importance of distributed empowerment increases dramatically. This puts pressure on project managers to establish trust as quickly as possible during the planning stage of the virtual project. (See Chapter 2.)

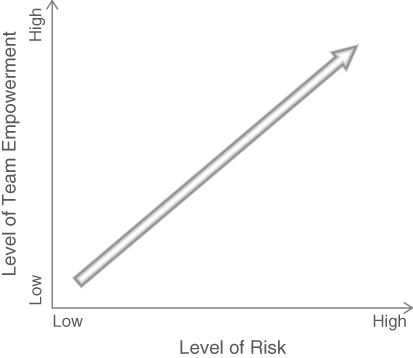

Empowerment–Risk Relationship

For virtual project managers, team empowerment is a double-edged sword. On one side, empowerment is absolutely necessary for success in a situation consisting of distributed resources. On the other side, empowerment of distributed resources means taking on greater risk. (See Figure 6.6.)

Figure 6.6 Empowerment–Risk Relationship

The more virtual project managers share their power, the more they are betting that the team can and will perform effectively when using that power on their own. The greater the empowerment, the less control project managers maintain.

This paradigm shift to decentralized power causes problems for some project managers as they first encounter the world of virtual projects. The natural tendency is to try to control risk as it emerges and increases on a project. The greater the risk, the greater the direct control project managers want to exert. Unfortunately, people who strive to assert a high level of control do not fare well as virtual project managers. Team empowerment is required as well as the distribution of the responsibility to manage risk on the project.

Team member empowerment is even more critical when the project is distributed internationally. Often there is no other choice but to empower those closest to the work in order to accurately evaluate a situation and decide on the proper course of action. Slow and ineffective problem solving and decision making (which are common in decentralized models) are primary causes for schedule delays and budget overruns on virtual projects.

Because trust takes longer to develop on global projects, team empowerment is even more risky. The rate at which power is shared may therefore be slower than in domestic virtual projects. As Victor Burdic, a seasoned virtual project manager, points out, “Empowerment is something that builds over time through gaining confidence in the team.” He also describes the consequence of empowerment risk: “One big screw-up on the part of someone wipes out 10 ‘accolades’ the team has received because of the loss of trust and confidence of the project manager.”

The most powerful tools for virtual project managers to use to lower the risk associated with distributed project teams are clearly defined success criteria, clearly defined deliverables and due dates, and decision boundaries based on the success criteria for each deliverable. Greater empowerment, with wider problem-solving and decision boundaries, can be granted as time progresses and trust increases regarding the team's ability to function in a decentralized manner.

Shared Decision Making

As we learned in Chapter 1, a common ailment affecting virtual teams is slow decision making. Traditional projects benefit from co-located team members who can assemble and engage in a rich discussion concerning a particular decision. Virtual teams do not have this luxury, and the separation of team members by time and distance can inhibit timely decision making. To combat this challenge, modifications to project management decision processes have to be made.

On traditional projects, project managers are the primary people providing project leadership. On virtual projects, however, leadership typically is shared among team members based on location and task at hand. This includes decision making. A more complex centralized/decentralized decision framework has to be established for virtual projects. Decisions that directly affect the success of the project—such as those that can change the project schedule, for example—need to remain centralized with project managers. Other decisions need to be decentralized and moved to where the decision outcome will be implemented. These decision types, such as the hiring of a particular project team member, become the responsibility of the project lead in the appropriate location who can effect more informed and timelier decisions. Decentralized decision making increases the probability that the right team members and stakeholders are involved in decisions and that the required data and information are available.

To make the shared decision process work on a virtual project, project managers must empower the virtual team members to whom they have delegated decision responsibility and authority. With authority granted, project managers must also communicate who has been delegated decision rights for the project to complete the empowerment process. (See the box titled “Planned Decision-Making Methodology for Maxwell's Virtual Project.”) This is best documented and communicated via the team charter. (See Chapter 2.)

Decision Alignment

Delegation of team decisions, however, increases the risk that the decision outcomes can become misaligned from the goals of the project. As a safeguard, team leaders must establish boundary conditions that serve as guardrails to prevent goal misalignment. The more concisely and clearly the boundary conditions for a decision are stated, the greater the likelihood that the decision will be effective in accomplishing the direction that is needed and ensuring that the direction is consistent with the business goals driving the need for the project.

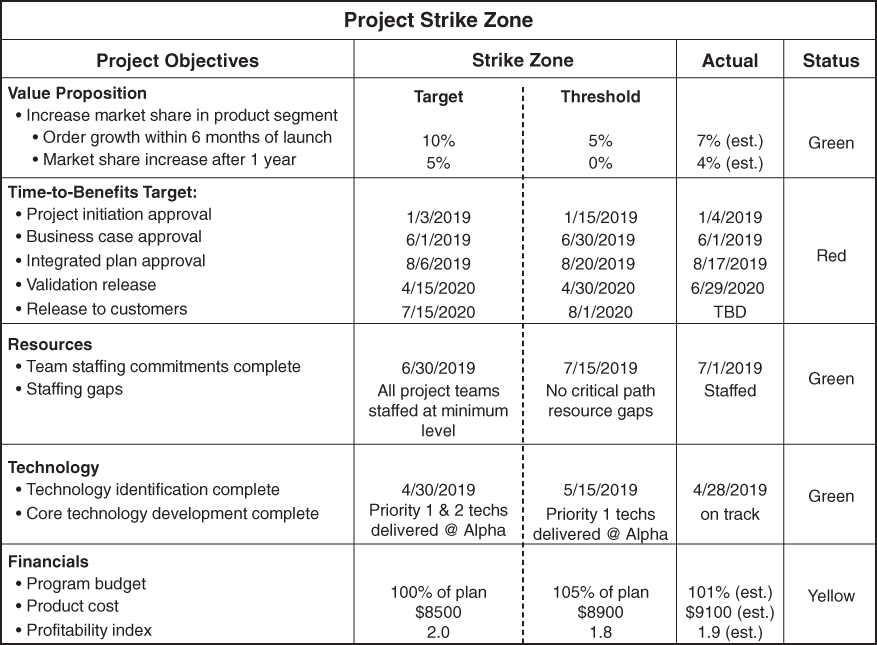

A wonderful example of a best practice for establishing team decision boundaries based on business goals is the use of a tool known as the project strike zone, which was introduced in Chapter 4. The project strike zone (shown again in Figure 6.7) is an important decision support tool that helps to keep project decisions in alignment with the business goals of the project.

Figure 6.7 Project Strike Zone Sets Decision Boundaries

The elements of the project strike zone include the business success factors for the project, target and control (threshold) limits, and a high-level status indicator. The success criteria thresholds are the decision boundaries within which the virtual team must remain. As long as a decision will not cause the project to move outside of any of the success criteria threshold limits, the delegated decision makers are empowered to make that decision. If, however, a decision will cause the project to move outside of any success criterion (e.g., product cost), the decision must be elevated to the project manager first and then possibly to the sponsoring executive.

In practice, not all decisions can be delegated to the local level. Whenever a decision outcome will affect more than one project subteam, affect others outside of the project team, or affect the project goals, the decision must be made by project managers. In these cases, project managers must ensure that they have the appropriate information to achieve a high-quality decision outcome.

Prescriptive Decision Methodology

With decisions distributed across the virtual project, the opportunity for inefficiencies due to variation in decision methods is great. To combat this, a common decision method should be prescribed by project managers and established across the virtual team. We have repeatedly witnessed the natural desire to include distributed team members in both consensus and majority rules decision methods with little success. Although the intention is correct, these decision methods are highly ineffective for virtual teams and result in significantly slow time-to-decisions.14

Consensus decision making strives to ensure all team members agree with what decision to make. Most of the time striving for consensus leads to exhaustive debate and can lead to circular discussions as team members toil in vain to convince others that their opinion is the right opinion. They fail to consider opening their own minds to other opinions and viewpoints. This method eventually can lead to false consensus where team members relinquish their opinion to the majority. This may be a result of having become exhausted with the circular discussions or a factor called conformity. Conformity arises in group decisions because people like to be liked. As a result, they conform to the opinions of others in order to prevent people from disliking them. It is in part for this reason we do not see “don't like” options on social media sites. We find that when either discussion exhaustion or conformity occur, disengagement once a decision is made is likely to occur.

Using a majority-rules decision method is also not recommended for virtual projects. Virtual projects often are structured in such a way that a larger number of team members are located in one or a small number of locations, with other team members distributed in smaller numbers. A majority-rules decision method can be a problem when it leads to coalition building among members who are co-located in greater numbers. Again, there is a high probability for team member disengagement in the decision process, particularly those who are distributed in smaller numbers.

The conclusion to be drawn here is that virtual project managers should avoid both consensus and majority-rules methods for decision making processes in order to accelerate time-to-decision performance and to decrease the likelihood of postdecision disengagement. Rather, the consultative decision method has proven to be highly effective for virtual projects. In consultative decisions, a single decision maker has sole responsibility for making a decision, but only after consulting with and drawing opinions from the other decision participants.15 Listed below are the elements required for effective consultative decision making on virtual projects:

Table 6.1 Example Decision Matrix

| Cost (30%) | Memory (20%) | Performance (40%) | Warranty (10%) | Score | |||||

| Options | Rating | Wt | Rating | Wt | Rating | Wt | Rating | Wt | |

| Laptop 1: Core i5 | 7 | 210 | 6 | 120 | 6 | 240 | 8 | 80 | 650 |

| Laptop 2: Athlon X4 | 8 | 240 | 6 | 120 | 4 | 160 | 10 | 100 | 620 |

| Pro Laptop: Core i7 | 5 | 150 | 10 | 200 | 9 | 360 | 6 | 60 | 770 |

| Desktop: Athlon FX | 4 | 120 | 5 | 100 | 8 | 320 | 6 | 60 | 600 |

- Ensure there is a single decision maker.

- Make sure all decision participants have been heard.

- Appoint a devil's advocate to circumvent group think.

- Give opportunity for new perspectives to be raised.

- Ask if anyone cannot live with the decision made.

- Strive for disagree and commit from those who don't agree with the decision. (See the box titled “If I Disagree, Why Do I Have to Commit?”)

Decision Matrix

To ensure consistency with the distributed decision making process necessary on virtual projects, some project managers use a tool called the decision matrix. A decision matrix is a table used to evaluate possible alternatives to a course of action.17 It is used primarily to help decision makers assess and prioritize all of their options before making a final decision and setting a course of action for the project team. The decision matrix is particularly powerful when a decision maker has a number of good options to choose from. It can be used for almost all decisions where there isn't a clear and obvious preferred option. For virtual projects, it serves an additional purpose. It provides consistency in decision making methodology.

A decision matrix can be created on a sheet of paper, but it is recommended that you create a form or spreadsheet that can be reused as new decisions are encountered. Table 6.1 shows a simple decision matrix created as a spreadsheet.

To use the decision matrix, list all decision options in rows and all the relevant factors affecting the decision in columns. For example, to decide what computers to purchase for a project, factors to consider might be cost, memory size, performance, and warranty terms. Some decision makers add a weighting to each of the factors to prioritize the importance of each factor in the decision process. We recommend this approach because it creates greater numerical separation in the final scores, making the highest-priority option more obvious.

Once the matrix is set up, work down each of the columns of the matrix, scoring each decision option based on the factors. A scoring range from 0 (poor) to 5 (very good) is recommended. Next, if weightings are used, multiply the original rating for each column by the weighted rankings to get a score. Then sum all of the factors under each option. The decision option that scores the highest is the option that should be given first consideration.

The decision matrix offers four important benefits to the decision maker:

- Understanding why and how one option is chosen over another.

- Aligning decisions with priorities.

- Evaluating decision alternatives on their own merit.

- Using logic rather than emotion for decisions.

As mentioned earlier, project managers should own and maintain a centralized decision log that documents the decisions made, when they were made, and who made them. The decision log provides virtual project managers a means of keeping track of the various distributed decisions that have been made by the empowered decision makers. The decision log, therefore, becomes a key artifact in the centralized governance of a virtual project.

Staying Connected through Effective Communication

Communication is defined as the ability to transmit ideas, receive information, and interact with the environment.18 Effective communication is crucial to the success of any project, as success is dependent on the effective transfer of information among project team members as well as with project stakeholders. This information exchange is needed to complete project tasks, solve problems, create work outcomes, make good decisions, and perform all activities that are core to project work. For virtual projects, effective communication is even more than this. Since a virtual project is a networked organization, communication is the heartbeat of the project. It is first necessary to establish the connections among distributed team members, and then it keeps the connections healthy throughout the project life cycle.

Previously, we stated that trust is the foundational element that binds the project network and enables the distribution of power from the project core to key team members located where work is performed. Extending that assertion further, it is effective communication, along with consistency of behavior that maintains trusting relationships among team members and between the team and its stakeholders. As a virtual project becomes increasingly decentralized, it is communication among team members that serves the role of keeping the project network intact.

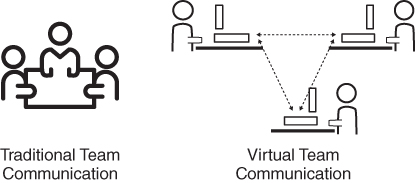

In Chapter 1, one of the primary differences between traditional and virtual projects presented was that communication is more difficult on virtual projects than on traditional projects. A simple diagram (see Figure 6.8) illustrates this challenge.

Figure 6.8 Traditional versus Virtual Communication

Traditional teams have the advantage of physical presence where communication can occur face-to-face. Only a portion of information exchanged between two people is accomplished through verbal exchange. The remaining information is transmitted via other means, especially through the sense of sight. It is common knowledge that when the transfer of information between people occurs, body language adds significantly to the effectiveness of the communication.

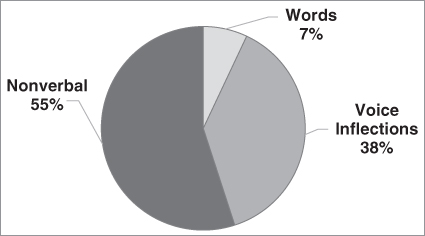

One of the foremost researchers on the topic, Dr. Albert Mehrabian, claims that only 7% of all daily communication is accomplish by words alone, meaning a full 93% of communication is accomplished through something else.19 Specifically, Mehrabian's studies concluded that 7% of any message is conveyed through words, 38% through certain vocal elements such as pitch and tone of voice, and 55% through nonverbal elements. (See Figure 6.9.) These nonverbal elements include facial expressions, gestures, and posture.

Figure 6.9 How Information Is Transferred between People

The exact breakdown of verbal versus nonverbal communication is irrelevant. The important point is to know that most communication is nonverbal. This is a powerful advantage for traditional project teams and a significant barrier to overcome on virtual projects. Because virtual team members cannot use nonverbal communication, they lose the ability to receive important clues that tell them messages were not fully received, were received as intended, or were not received as intended. The receiver of the messages also loses the ability to pick up on any emotions behind the sender's words.

Another factor that doesn't play in favor of the virtual project team is communication effectiveness related to the physical distance between people. Studies have shown that even traditional, co-located teams will communicate less if team members work more than 25 feet from one another.20 Increase that distance to 100 feet, and the probability that two people will communicate face-to-face more than twice a week falls below 50%. The distance separating team members on virtual teams degrades communication even further if the team has to rely exclusively on written or verbal communication, and further yet, if team members do not share a common first language. (See below “Global Communication Challenges.”)

Finally, project team size can negatively affect communication effectiveness. Not surprisingly, the larger the team, the greater the communication barriers among team members. The three most significant factors contributing to this decay in project information transfer are the fact that (1) the number of communication channels that have to be established and maintained increases; (2) the number of specialties (with specialized terminology and jargon) increases; and (3) physical distance between team members usually increases when the project is virtual.

When we add these factors to the fact that virtual project teams must communicate with one another via technology, we can clearly understand why communication is a significant challenge on virtual projects. What does all this mean? Stated simply, it means that knowledge workers working in virtual project environments have significant “overhead” associated with purposeful communication that others working in traditional project environments do not have. In addition to the focused effort required by virtual project teams to complete tasks and outcomes, significantly more time and effort must be focused on how team members communicate with one another. (See the box titled “The Five Cs of Good Communication.”) Virtual communication must be purposeful, concise, and intentionally conducted on a regular basis.

To help ease the communication overhead, use as much synchronous communication as possible on projects. Encourage team members to use phone conversations (even if they are intercontinental) between one another instead of long email exchanges that can span many hours or potentially days. We underscore the importance of using synchronous communication for the sake of context if for no other reason. Synchronous communication allows for a continuous stream of questions and answers that provide the necessary reasoning behind a core message. This is especially important when communicating decisions or working to solve project problems.

Another important way to lower communication overhead and increase communication effectiveness on virtual projects is to establish more focused team meetings than just weekly status meetings. For example, break the typical long status update meeting into three separate meetings where performance to schedule and work accomplished is discussed in one meeting, project change management and risk management are the topic of a second meeting, and technical information exchange is the focus of the third meeting. Take advantage of video conferencing technologies whenever possible to bring in nonverbal communication. Desktop video conferencing and other tools are readily available for use on virtual projects to combine both verbal and nonverbal communication among team members and other project stakeholders. With the potential for more team meetings as a method to increase cross-team communication effectiveness, it is important to know how to conduct an effective project meeting.

Effective Team Meetings

Anyone who has had the task of conducting meetings on a virtual project will attest to the fact that they can be significantly more difficult and unproductive than meetings on a traditional project. As a result, it is common practice to attempt to replace the virtual meeting with email exchanges. Predictably, the team learns that the time required to have sufficient back-and-forth exchange on project topics via email can be significant. Chapter 8 discusses how to be concise in writing effective emails, a good practice to adhere to. However, much of the content eliminated in emails for brevity's sake is context about why the transmitted information is important or how it pertains to the particular project situation. This results in several additional email exchanges between sender and receivers.

Instead of attempting to replace synchronous team meetings with asynchronous email exchanges, virtual project managers must focus on running effective team meetings. Effective team meetings are those that ensure adequate benefit is received in exchange for the time a meeting consumes. Team meetings should provide a forum for virtual team members to interact with one another, to discuss problems that have been encountered, to bring forth issues and potential risks that need attention, and to share ideas with one another.

Virtual team meetings have a different energy than those where people meet face-to-face around a conference room table. They have a different pace that is due in large part to the fact that work is being accomplished as team members discuss their work.22 In many cases, work products (documents, diagrams, presentation, and so on) are created and modified during virtual meetings.

In contrast to traditional project team meetings that can be arranged quickly and often informally, team meetings on virtual projects must be more purposeful, proactively planned, and organized. As mentioned earlier, virtual team meetings must be narrower in scope and attendees. Unlike team meetings on a traditional project, where a large number of topics can be covered effectively, virtual team meetings should be limited to two or three primary topics. People get weary in virtual meetings if too much time passes and too much information is discussed. Limiting the scope will allow adequate time for additional discussion to ensure understanding and required actions.

Even with the narrower scope of virtual meetings, adequate preparation and planning is needed. See Table 6.2 for a sample virtual meeting preparation checklist. The first thing to plan is the meeting time. As Adit Liss, a seasoned project manager for Ikamai Technologies, explains, “This can be a challenge if multiple time zones are involved, especially if team members live in different parts of the world. On my previous project, I had team members in two locations in India, on both the West and East Coasts of the United States, in Germany, and in Israel. Finding a reasonably acceptable time for our weekly team meeting was tough. We finally settled on 7:00 AM on the U.S. West Coast, which was 7:30 PM in India, 10:00 AM on the East Coast of the U.S., 4:00 PM in Germany, and 5:00 PM in Israel. I feel fortunate that I am only juggling three time zones on my current project.”

Table 6.2 Virtual Meeting Preparation Checklist

| Status | Checklist Items |

| ✓ | Primary purpose of the meeting defined and communicated |

| ✓ | Expected outcomes identified |

| ✓ | Facilitator(s) identified |

| ✓ | Detailed agenda completed |

| ✓ | Start and stop times defined |

| ✓ | Presenters identified and notified |

| ✓ | All decisions to be made clearly communicated |

| ✓ | Materials sent to participants at least 24 hours prior to meeting |

| ✓ | Access to meeting technology available to all participants |

| ✓ | All participants sufficiently competent in the technology |

| ✓ | Technology is reserved, set up, and tested |

| ✓ | Participants have all access codes required |

| ✓ | All security measures identified and taken |

The next things to consider are the medium and technology that will be used—video conferencing, audio conferencing, document sharing, and so forth. With time, medium, and technology planned, basic good practices for meeting effectiveness should be followed. These include clear meeting objectives and outcomes, a specific and detailed agenda, communicated expectations to those required to present information, and all materials sent to meeting participants prior to the meeting.

For virtual meetings, it is useful to provide visual aids. Visual aids help to provide focus for the discussion and can also help the meeting participants feel more like teammates. This is particularly true if the visual aids are products of team collaboration, such as project diagrams or research findings. The use of visual aids allows for two simultaneous communication threads: one visual in nature, the other conversational.23 See the box titled “Virtual Team Meeting Protocols” for additional guidance for facilitating a virtual team meeting.

Once a virtual meeting is adjourned, the job of project managers as meeting facilitators is not complete. Project managers also need to attend to the conversations that continue after the formal meeting. One of the underlying goals of all virtual team meetings is to enable more communication and collaboration among team members to strengthen the project network. Project managers must be willing to participate in and facilitate follow-on conversations to ensure that this communication and collaboration is taking place.

Centralized/Decentralized Project Construct

“I remember sitting in Brent Norville's office last year when he drew a centralize/decentralize diagram on his whiteboard and explained that the diagram describes a primary construct for virtual projects,” explains Jeremy Bouchard. “When I took on my first virtual project, I was lost in the diffusion of information and distribution of people and didn't understand that it was my job as the project manager to orchestrate the centralization of much of the information and then broker the distribution back out to the various distributed team members.”

This was an important learning for Bouchard as he continued his transformation from traditional project manager to virtual project manager. On traditional projects, the centralized/decentralized aspects covered in this chapter occur organically and mostly by nature as a result of physical and social presence between project manager and team. On virtual projects, however, centralization and decentralization activities have to be purposefully designed, planned, and implemented by virtual project managers.

Assessing Virtual Team Collaboration

The level and effectiveness of project teamwork has a major impact not only on team performance, but also on project outcomes and the ability to achieve business goals. The Virtual Team Collaboration Assessment evaluates team success criteria that research has shown to be necessary in reaching high levels of performance.

This assessment is intended to be used by project teams and organizational managers when evaluating team effectiveness. Collaboration cannot be mandated, but it certainly can be taught, be an organizational expectation, and be intentionally designed into project work. Therefore, the results from this assessment can be used to coach and train virtual project managers and team members on good communication and collaboration practices. The assessment is meant to evaluate the project team as a whole, although reviewers of the assessment may want to use the notes section on each item to document any individual specific comments.

Virtual Team Collaboration Assessment

Date of Assessment: __________

Virtual Project Team Code Name: ___________________________

Virtual Project Manager Name: _____________________________

Project Start Date: _____________

Planned Completion Date: _____________

Team Size: ________

Assessment Completed by: ________________________________

Confidential Assessment: ______ Yes, confidential

______ No, not confidential

| Assessment Item | Yes or No | Notes for All No Responses |

| The virtual project leader possessed excellent collaboration skills. | ||

| All team members successfully participated and were actively engaged at all project locations. | ||

| All project core team members were actively engaged in drafting the team charter. | ||

| All project core team members were actively engaged in drafting the project mission. | ||

| All project core team members were actively engaged in drafting the project scope. | ||

| All project team members reviewed and understood the project business case. | ||

| All project team members were actively engaged in drafting the stakeholder list, analysis, and communication plan. | ||

| All project team members reviewed and understood the whole solution diagram. | ||

| Cross-team interdependencies were mapped and owners assigned across all project locations. | ||

| There was a concise vision or goals statement for the project, and it was communicated to the team. | ||

| Project risks were identified and discussed, and mitigation plans established. | ||

| Honest feedback was solicited from all team members and actively provided by all. | ||

| Project team meetings and discussions were objective, with ample time provided for questions and answers. | ||

| All assumptions were identified and dealt with immediately. | ||

| Any information that deviated from plans was raised proactively and resolved quickly. | ||

| Team norms were documented and reviewed on a periodic basis. | ||

| There was a high degree of confidence in the team's ability to succeed at all project locations. | ||

| Each team member understood his or her role and the importance of that role in accomplishing the project's business goals. | ||

| Team members listened to one another. | ||

| Team members would seek to learn from each other and take every opportunity to coach and teach others on the team. | ||

| An initial face-to-face meeting was held during the early stages of the project. | ||

| Distributed teams had sufficient resources to conduct their work. | ||

| Decision rights were granted to specific distributed team members. | ||

| Decision logs were in use. | ||

| A culture of “disagree and commit” was in place on the project. | ||

| If appropriate, team members serving as cultural liaisons were assigned to the team. | ||

| A project communication plan was in place. | ||

| Common collaboration tools were in place, all team members had access, and team members were trained on the use of the tools. | ||

| Team meetings were scheduled ahead of time and could be supported in all project time zones. | ||

| Team meetings had specified agendas. | ||

| Proper virtual meeting etiquette was practiced in team meetings. | ||

| Findings, Key Thoughts, and Recommendations | ||