CHAPTER 5

LEADING THE VIRTUAL PROJECT TEAM

When a firm begins to perform its project work virtually, success is often due to heroic efforts on the part of the project manager and a number of his or her team members. Achieving success consistently becomes a shared responsibility between project manager, project team, and senior leadership. It is the job of the senior leaders to establish a virtualization strategy and to remove any barriers to virtual execution success. The company's project managers are responsible for consistently ensuring their virtual projects are executed successfully and that business value is captured. If both pieces of the organization work effectively together, a continual increase in virtual project maturity and repeated success can be expected. As we underscore in this chapter, repeatable success in virtual project execution has to do with solid project management practices plus strong project team leadership.

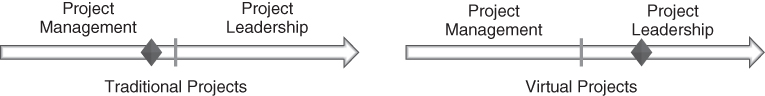

As discussed earlier, all project managers have two primary roles: managing the project and leading the team. Many project managers experience a shift in the amount of time and effort spent in these two roles when they move from managing traditional projects to managing virtual ones. As Figure 5.1 illustrates, the balance of effort shifts to the right of the management-leadership continuum for a virtual project.

Figure 5.1 Virtual Projects Require a Shift in Focus

This is not to indicate that team leadership is more important than good project management practices. Quite the contrary, project management practices have to be performed effectively no matter what type of project is being managed. The difference is that for a virtual project, work has to be performed through team members who are much less accessible and are loosely connected organizationally. Therefore, influencing from a distance is required, communication from a distance is required, and monitoring of work from a distance is required.

In short, the distance factor caused by the team's distribution requires additional effort and strong team leadership practices on the part of project managers. Contrary to what some project managers have come to fear, however, managers of virtual projects do not need to acquire a completely new suite of skills and competencies to succeed in leading virtual project teams. The foundational elements of effective team leadership apply whether project managers are leading traditional project teams or virtual project teams. As Jeremy Bouchard and others have come to learn, success begins with proficiency in the basic principles of team leadership and then an understanding of how to extend the leadership principles to apply to virtual teams. Over time, the basic leadership principles are augmented with additional processes, tools, and skills to increase effectiveness, given the cultural, distance, time, and communication challenges that virtual projects present.

Understanding the basics of project team leadership begins with understanding the various roles project managers play when leading teams of project specialists. It all begins with setting a common direction to channel team energy and work output.

Be the Project Compass

Project managers, acting as project leaders, are responsible for setting the direction for the project. Setting a common direction for a virtual team is a vital role, as virtual team members often scatter their work effort in many different directions. Like all project teams, virtual teams contain a high level of human energy that drives team members to want to contribute in some way to project success. Without clear direction, that energy will be scattered and unfocused, diminishing the power that can be gained from collective human energy. A simple analogy is that of a search party whose job it is to locate a missing item in a large geographical area (such as a five-acre area of trees and brush). If a search party of 20 people must search on their own to find the item, they will scatter in 20 different directions, and the result will be duplication of effort, territory that will remain unchecked, and a high level of inefficiency of human effort. We have learned that the effort of these 20 searchers is much more productive and successful when they are organized, structured into a line, each given an area of responsibility, and guided by a common direction of search. The search leader in effect serves as the human compass for the search team. In similar fashion, project leaders have to serve as human compasses for virtual project teams. To do so, they must know exactly where they are leading the team and what direction the team needs to be heading. This is accomplished through the creation of a project vision.

Project Vision

In Chapter 3, we discussed the need for a project team to have a common purpose or mission in order to build team chemistry and help team members attach to a common and meaningful purpose for their specific work on the project team. At times, the project purpose or mission is confused with the project vision. Two key words help to distinguish between mission and vision, why and what. The project mission defines why the project is needed. For example, the mission of a project may be to increase market share or revenue, to reduce operating costs, or to enter a new business segment.

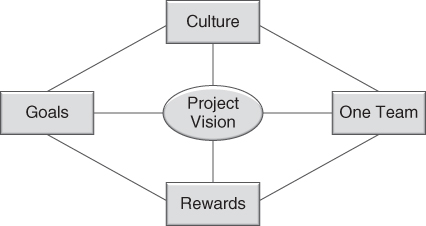

The project vision, in contrast, defines the project end-state, or what is to be accomplished by the project outcome. The vision, in effect, helps to define the organizational goals to be achieved through the investment in the project. (See Figure 5.2.)

Figure 5.2 Project Vision

However, while leading project teams, project managers can use the project vision for more than just establishing project goals. One of the essentials of strong leadership is that leaders pull on the energy and talents of team members rather than pushing, ordering, or manipulating team members. Leadership is not about imposing the will of the leader, but rather about creating a compelling vision that people are willing to support and are willing to exert whatever energy is needed to realize it.1 The project vision is the vehicle that project managers use to pull the team together and establish a sense of we instead of me. This “One Team” mentality is important for virtual projects, as it is necessary for all team members to put team goals ahead of functional or organizational goals. Without a compelling project vision, team goals will become subservient to individual and organizational goals. The means by which team members are rewarded has to be designed in such a way that reinforcement of team goals has priority over functional goals.

As the virtual project team begins to view themselves as “One Team” with a common purpose and vision, a unique project culture begins to form. Team culture, a micro culture of both organizational and national culture, is important to establish because it helps to create a unique team identity and operating principles. Team culture is powerful because it is formed by shared experiences that solidify beliefs, values, assumptions, and behaviors. At this point, the team is moving beyond norming and storming to (high) performing. To establish a positive project culture, project managers must first recognize their role in doing so. Second, project managers must intentionally design the means to positively affect the culture of the team by articulating a clear mission, developing a shared vision of the team's identity, and providing team-building opportunities.

Be the Team Conductor

The analogy of the role of project managers as being similar to conductors of orchestras who must keep all players synchronized in time and playing complementary parts from the same sheet of music has been used many times. Just as an orchestra is composed of multiple instrumental elements (e.g., the string, brass, and percussion sections), a project is composed of multiple functional elements (e.g., design, development, and manufacturing). Alignment of all project elements is a critical factor in project success and a primary leadership challenge for project managers.

Gone is the time when project team leadership is authority driven with work being performed through a series of directives. Today's era of project team leadership is more diffused, collective, and team-based, where directives and decisions are participatory, collective, and democratic. Project managers success in the role of team leader is dependent on how well they facilitate the alignment of interests, work activities, and the collective outcome of the project. (See Chapter 9.)

Product and service solutions are now too complex to be developed by a single expert. The integration of work from a team of specialists who focus on creating their piece of the solution is required. However, specialists do not by nature desire to work in a collaborative and participative manner. They would prefer to be left alone to create their piece of the solution and hand it off to someone else to integrate and use.

Unfortunately for specialists, this type of development has been proven to be highly inefficient and ineffective and has led to the need for collaborative cross-functional work teams. Surrounded by specialists, the role of project team leaders becomes one of initiating and driving continuous, cross-team collaboration.

When leading a highly distributed team, project managers have to work even harder to drive effective participation and collaboration between members who are separated by time and distance. This is due primarily to the fact that participation and collaboration—as well as integration of work output—has to be performed asynchronously and electronically.

The physical distance that separates virtual team members limits the amount of synchronous collaboration. Because face-to-face meetings and discussions are limited, time delays occur due to the additional iterations of communication and work that result from trying to collaborate electronically and at different times. Relatively routine tasks, such as scheduling a meeting, can become complex when one person's workday is beginning while another is sitting down to dinner.2

Time differences and physical separation can also allow some of the more introverted members of a team to get lost in action—meaning their team participation and collaboration can become lost due to their innate personalities. Project team leaders must exert focused effort to keep these people active and engaged.

Integration of work output also becomes more complicated on virtual projects. Work is accomplished in a very fragmented manner on a distributed team, and it will remain fragmented unless project team leaders purposefully establish and manage integration of work between members.

Effectively driving collaboration, participation, and integration of work output, therefore, requires a change in both behavior and some processes. To first establish broad participation of team members, team leaders must focus on some critical behaviors. They must be willing to listen first, not tell their team what they think first and then ask for opinions. A more effective way to increase member participation is for team leaders to ask for input and opinions first, facilitate a discussion as a team, and then share their own opinions. By doing so, team leaders are motivating the team through inclusion. Through deliberate provocation of opinion from the team, team leaders help them become more comfortable with participating and sharing their opinions over time.

Another effective approach for driving a high level of collaboration between members of a virtual team is to organize the team's work in such a way that the team members are mutually dependent and they recognize the benefit of that mutual dependency. One of the intangible benefits of creating a project map that clearly highlights team interdependencies as covered in Chapter 2 is that the map demonstrates that a high degree of collaboration is required for the team to succeed in creating the project output. Additionally, the mapping process itself helps to build the virtual team as a cohesive entity.3 This is especially true if the mapping process is performed in a face-to-face session where at least the core members of the geographically distributed virtual team meet, work together, and begin to build professional relationships with one another. Using the project map throughout project execution is an effective way to stress the need for continual collaboration and to orchestrate the integration of work outcomes.

Be the Champion

It is true that a project team needs good direction and a vision of success. It is also true that team members need help coordinating and integrating their work outcomes, especially when they are geographically and organizationally distributed. And, equally important, teams need leaders who will listen to their ideas, concerns, and needs and who will help them take responsibility to meet their own goals.

Good project team leadership, then, is not only about accomplishing team goals and purposes, but also about creating a motivating team environment built on trust and then empowering team members so they can prosper and grow in the process. Project managers truly champion the efforts of the project team members. Team leaders must strive to enable the team to succeed and to set expectations that the team members will make decisions, solve problems, and collaborate effectively. A major factor in the enablement of a virtual project team to achieve self-sufficiency is how well project managers motivate their teams.

Motivating the Virtual Team

It is no surprise to virtual project managers that recent findings show project team member motivation is critically important to success, or that the importance of motivation is equal for both traditional and virtual projects, or that fostering motivation is particularly more challenging on virtual projects than on traditional ones.4

Two of the subtleties that have emerged specific to motivating a virtual team are interesting for virtual project managers to consider. First, social interaction has emerged as a factor in sustaining motivation on project teams. Obviously, virtual projects hamper social interaction by nature, and severely so in highly distributed virtual projects. Second, it is recognized that senior-level people on project teams are more difficult to motivate and keep motivated. Having spent a good portion of their career on traditional projects, senior-level employees seem to have a more difficult time adapting to the virtual project environment than less experienced team members. This difficulty can, in fact, become a demotivator. Another factor affecting motivation of senior-level employees is previous fulfillment of motivating factors. As we explain later in the chapter, motivators tend to be intrinsic, or internal, in nature. And these intrinsic motivators do not change much over time. The result is that the longer a person's career, the more likely that his or her internal motivators have already been fulfilled.

With these two subtleties in mind, we explore the subject of motivation on virtual teams from a wider landscape.

The title of this section is quite misleading. It leads readers to believe project managers can indeed directly motivate the members of the virtual project team. Despite the millions of dollars spent each year on motivational speakers and workshops that teach us how to motivate our teams, it is understood that people, including the people on project teams, are in fact self-motivated.

Consider individuals on a project team who seem completely unmotivated. What happens to them when they go home to their families, their hobbies, or other important aspects of their lives at the end of the workday? Odds are high that they become very motivated individuals. The person does not change, but the climate and atmosphere of their environment in fact changes. What are we trying to convey? Simply put, virtual project team leaders cannot motivate their teams directly; motivation has to come from within the individuals. It is key to understand that the role of team leaders is to create a motivating climate for project team members.

Among project team members who are self-motivated, intrinsic factors (those that are personally rewarding) are more important than extrinsic factors (those that provide reward or punishment avoidance) for creating and sustaining motivation. The panel of virtual project team members (a virtual team in itself) who participated in the research for this book confirmed this assertion. When asked what motivates them most in the workplace and project environment, they provided these answers:

- New challenges, being able to try new things and either succeed or fail.

- Seeing their team complete a project successfully.

- Knowing that their part of the project made a big contribution to the overall project.

- Pushing themselves to new levels and learning new technologies and techniques.

- Having the opportunity to work on diverse types of projects.

- Being able to work with and get to know people from around the world.

All of these factors are related to the internal gears that drive each individual with little or no connection to external factors (such as paychecks, incentives, or bonuses). Research shows that intrinsic motivators are even more important on virtual projects. The more virtually distributed a team is, the weaker the social bonds and personal interaction; therefore, the more team members have to rely on internal factors to remain motivated.5

This does not mean, however, that extrinsic motivators such as a competitive salary or bonuses for a job well done are not important to keep the individuals working at the same level of motivation. If extrinsic factors are not also considered, they can indeed become demotivators. Consider this question: Would you as a project team member remain highly motivated if any or all of these extrinsic factors were present in your project environment?

- The project lacks clear goals and success factors.

- You are asked multiple times to rework your part of the project because the overall project direction continues to change.

- You feel isolated from the rest of the team.

- The work you do lacks challenge.

- You fear retribution if you make a mistake.

- You lack the power to make necessary decisions needed to keep your work progressing.

Therefore, the key point for virtual team leaders to remember is that they are responsible for creating a motivating climate; virtual team members are personally responsible for finding the things that motivate them the most within the environment and following through to project completion.

Creating a Motivational Climate

For project teams to succeed, the climate in which team members work must be positive, inspiring, forward-moving, and motivational. There are many opinions on what project climate means, but to us it is what employees feel and experience when they work as part of the project team and become acquainted with the team culture, the project vision, how team members interact with one another, and the project manager's leadership style. If team members like what they feel and experience, they will begin integrating their individual intrinsic motivators with the project. Project managers must create opportunities for achievement, provide adequate resources to succeed, assist the team in knocking down barriers to progress, give recognition for good performance, and help team members feel like they are an integral part of the team.6

Additionally to the team culture, climate and organizational considerations, one of the most important factors in establishing a motivational project climate is empowerment. This means that project team leaders are willing to share power with the team to set goals, make decisions, and solve problems. No one likes to be micromanaged, and in today's work environment, nothing will demotivate team members faster than a micromanaging team leader and lack of empowerment. Instead of micromanaging, project team leaders must be willing to support team members' actions and efforts, provide recognition when the team succeeds, and coach them through their mistakes.

Remember, however, that empowerment and acting empowered take time as they go hand-in-hand with the process of establishing trust and navigating through the stages of team development. Project team leaders must become confident that team members will act in the team's best interest when making decisions, setting goals, and solving problems. Also, it is unrealistic to expect team members to assume a great deal of responsibility in the early stages of the project if they have traditionally worked in a more command-and-control environment. The transfer of power and responsibility most likely will need to be gradual. In fact, if empowerment is thrust on team members all at once, the result may likely be demotivation.7 Again, this is due to team members' feelings that they will be chastised if they make mistakes.

Table 5.1 Motivational Climate Survey

| Never | Sometimes | Always | |||

| I feel empowered to make the necessary decisions within my scope of work to keep the work progressing as scheduled. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I am given the authority and responsibility to solve problems within my scope of work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel empowered to assist my teammates in solving problems outside of my direct scope of work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel empowered to set my own work goals. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| The work I am doing is challenging. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel recognized for my achievements. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| There is an atmosphere of trust on the project. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| The project goals are clear. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel accepted as a valued team member. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I understand how my work contributes to the overall success of the project. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel encouraged to innovate and create new ideas and approaches. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| I feel I won't be punished for taking risks if I fail. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| COLUMN TOTALS | |||||

| AVERAGE OF ALL COLUMN TOTAL RESULTS | |||||

A positive climate for motivation is achieved when a fear of making mistakes is nonexistent and project team managers are willing to coach team members through the mistakes. For a virtual project, there is no option but to share power and delegate decisions, problems, and goals in a decentralized manner where they can be acted on quickly.

Assessing Team Motivation

A powerful question is often at top of mind for virtual project team leaders: How do I know if my team is motivated? The normal approach for assessing team motivation is to evaluate the progress toward task completion. The base assumption underlying this assessment approach is that if team members are doing their work, completing it on time and as tasked, it is an indication that they are motivated.8 It should be pointed out that there has been no proven causality between motivation and a team member's ability or willingness to complete work. The relationship between motivation and work progress simply remains an assumption.

Even though the validity of the work progress approach to assessing team motivation is debatable, the underlying problem that this assessment approach is trying to solve is that because there is a lack of face-to-face interactions on virtual projects, people need to rely on other cues to determine the level of team motivation. Jeremy Bouchard shared the following lesson learned from his first virtual team experience: “Because I was not in a room with my team personally, I had to rely on their perceived enthusiasm that was projected through their voices. I was listening for the degree of responsiveness they demonstrated during our conversations because I couldn't see their body language.”

For some ambitious (and we would call them brave) virtual project managers, we suggest a more direct approach—have team members take a motivation climate survey. (See Table 5.1.) Since team members are, by and large, motivated by intrinsic motivators, it makes little sense to assess if they are truly motivated. Rather, what needs to be assessed is whether virtual project managers have established a motivational project climate.

Once team members complete the survey, the results can be averaged for each question and then totaled. Obviously, the higher the sum total of the survey, the more motivational the team climate. Besides providing a quantitative assessment of the motivational climate on a team, the assessment can be used to make corrections in areas where the team members feel the motivational climate is low (columns with the lowest totals). For example, team members may not feel fully empowered to set their own work goals. Going forward, the project team leader can work more collaboratively with the team members on setting work goals and ensuring that they stay aligned with the overall project goals and outcomes.

Maintaining Trust

As we explored in Chapter 3, achieving a high level of team performance with a virtual team requires a solid foundation built on trust. Trust is created by the demonstration of proven interaction and consistency of behavior.9 An unfortunate reality is that trust between the project team members takes time and effort to establish, but can be destroyed quickly and easily. The same is true for trust between project managers and their teams. Maintaining trust on the team, therefore, becomes a critical factor in leading a virtual project team.

In many ways, virtual project managers are the glue that holds the team together. They must set the expectation that all team members demonstrate they are worthy of mutual trust. The following are ways in which that can happen.10

- Perform competently. With the absence of personal relationships on a virtual team (especially at the beginning of the project), team members will be evaluating each other and the project manager based on how competent they believe a person is within their role on the team.

- Act with integrity. Virtual project team members will closely watch and listen to determine whether other team members act in a manner that is consistent with what they say and within their stated values.

- Follow through on commitments. Similar to integrity, this means doing what you say you're going to do, whether it is completing a project deliverable, sending an email when promised, or scheduling a meeting in a timely manner. Those who follow through consistently are perceived as being more dependable and therefore earn team members' trust and confidence.

- Display concern for the well-being of others. People trust those who are perceived as responsive to the needs of others on the team and within the organization. Team members (and team leaders) who assess how their behaviors affect other team members most likely will be perceived as having more concern for others. In contrast, those who appear to be less sensitive to others will be viewed as less trustworthy.

- Behave consistently. Members of a virtually dispersed team look for a higher level of consistency of behavior among their fellow team members as a way to drive out some of the ambiguity within a virtual team environment. Trust on a virtual team is based on behavioral consistency rather than on social bonds. As project leaders have difficulty assessing trust through social indicators, they have to rely on consistency of behavior. The same goes for team members when building trust in the project manager.

One of the best ways to maintain trust is for virtual project managers to set the example. Team leaders who want team members to exhibit specific behaviors must ensure that they demonstrate, through their own actions, those behaviors. For example, project managers who encourage the team to act with integrity, show respect to others, and meet commitments must model those behaviors themselves.

It is difficult to separate trust between members of a virtual project team and team chemistry, as they are tightly interwoven. Project team leaders must try to ensure that positive team chemistry is maintained. Doing this requires a focus on maintaining social presence even though team members may be widely distributed. James Lehey, an experienced leader of virtual project teams, explains that this is not a difficult task.

Maintaining good team rapport does not require special effort. It only requires consistent effort. I find it beneficial to add social communication time into our weekly team meeting agenda, usually at the beginning of the meeting. The team also has a section on our team site where we share social experience and events. I use these postings as a way to end some of our meetings by asking a person to verbally share their experience with the team.

The sharing of personal experiences increases the social presence on a virtual team, which strengthens personal relationships among team members, which in turn strengthens trust.11 Team leaders must also be willing to meet face-to-face with team members at their various geographical locations when possible for local team meetings, one-on-one discussions, review of issues, and discussion of project progress. These efforts provide additional opportunities for project managers to reinforce teamwork and trust.

Virtual project managers must treat trust as their greatest asset and realize that it is important to consistently model the behaviors that exemplify competence, connection, and character in leading the team. The best virtual project managers we have encountered realize the need to go beyond establishing expectations that the team demonstrate the trust-building behaviors. The managers also model the behaviors on a daily basis by always standing behind and supporting their teams, never demonstrating favoritism, and accepting full accountability for the actions and results of their teams.

Demonstrating Personal Integrity

One of the surest ways to destroy trust and motivation on any team, either co-located or virtual, is for project managers to demonstrate a lack of integrity.

Team leaders who operate with integrity behave ethically and honestly, have an unwavering commitment to their values and are willing to defend them, are authentic in that they display their thoughts and beliefs through their actions, and consistently demonstrate responsibility and accountability. For proof of the importance of leaders operating with integrity, just review many stories in the press today that demonstrate the effects of lapses in integrity.

For virtual project managers, integrity is rooted in two foundational elements: values and vision. Values are what people stand for, and the team needs to see demonstrable proof of project managers' values in action. Vision is a clear end state of where project managers are taking the team. For project managers, this involves establishing transparency in the project and business success criteria that tell the team what it takes to be successful in their mission. Anyone can call themselves a leader if they have the knowledge and skills to perform the role. But, if their team members and constituents do not believe that that person uses leadership knowledge and skills with integrity, he or she is not really perceived as a leader.

Managing Conflict

It is impossible to maintain a conflict-free team environment, as conflict is a way of life when people work together. Conflicts typically emerge because people do not see everything the same way. Each member on a team will demonstrate personal preferences, personality traits, ideas, and opinions that occasionally lead to conflict among team members. In this manner, conflict is good! When managed properly, the differences in people's points of view can be a source of power for teams because they represent a broader perspective and more possibilities for creative solutions. The positive effects of constructive team conflict include identification of alternatives not yet considered, better solutions to problems, better decisions, more attainable goals, and broader buy-in across the team than if differences are not discussed. (See the box titled “Managing Virtual Conflict.”). A basic rule of conflict should be remembered: It is okay to disagree, but it is not okay to be disagreeable.

Of course, team conflict often has negative effects as well. The inability to effectively manage through conflict between project team members is a major source of team dysfunction. Causes of negative team conflict vary greatly depending on the situation and individuals involved. However, two of the most common causes are competing interests among team members and communication breakdowns. When these situations occur, negative team conflicts can result in reduced productivity, missed delivery dates, hoarding or not sharing vital project information, finger-pointing and scapegoating, reduced collaboration, low team morale, and high team member turnover.

Managing conflict on a virtual project can be a more difficult challenge for team leaders. On a virtual team, conflict can occur quickly due to the high potential for miscommunication, can go unnoticed for a longer period of time because most communication is performed electronically and asynchronously, and can be harder to correct due to a lack of direct face-to-face interaction. As one virtual project manager told us, “Problems resulting from a simple language miscommunication can take on a life of their own. A simple email exchange can end up frazzling nerves because of a simple cultural misunderstanding.”

Virtual project managers must be hypervigilant in identifying conflict among team members, because conflict cannot be resolved if it is not identified. Most times, virtual project managers are in the best position to notice conflict in email exchanges between team members or detect negative conflict during team discussions and meetings. As one team member observed, “A lot of leaders ignore conflicts between team members, hoping that they will just go away. But, they seldom do; they usually just get worse.” Conflicts among team members must be resolved quickly and to the team's satisfaction. Issues and conflicts cannot be left to fester. Avoiding issues with the hope that they will resolve themselves and disappear may backfire on team leaders later in the project.

It is not enough for virtual project managers to merely be good at spotting conflict on the team. They must also be quick to respond so it is less likely to spiral out of control. Being quick to respond, however, does not mean jumping in whenever a debate of viewpoints is occurring on a team. Virtual project managers must learn to get involved within certain boundary conditions, such as when conflict:

- Affects the performance of other team members.

- Jeopardizes achievement of team goals.

- Interferes with team communication.

- Overflows to external stakeholders or partners.

- Involves a repetitive pattern.

Outside of these boundary conditions, team leaders should allow debate among team members to continue if the debate is moving toward a positive outcome. Doing so will help build team cooperation, collaboration, and cohesiveness.

Understanding Sources of Conflict

It is also important for virtual project managers to become skilled in determining conflict type once a conflict is identified. Conflict type will determine the general course of action that team leaders will want to follow.12 Listed below are the key sources of conflict that can occur on virtual project teams.

- Task conflict. Task conflict results from differences in viewpoints and opinions pertaining to what the team is tasked to do. This type of conflict can be beneficial, and team leaders should encourage varying viewpoints. Task conflict can improve decision quality and ensure that the team is working on the most important set of tasks. Virtual project managers must act as facilitators by embracing debate, but also steer the outcome toward achievement of the intended business results.

- Process conflict. Process conflict involves debates regarding how the tasks are performed on the team or how resources are delegated to the tasks. In general, process conflict can be beneficial in improving the effectiveness and efficiency of the team's work, but continued debate can easily turn process conflict into relationship conflict. The virtual project manager must be vigilant in hearing all viewpoints concerning a process, but then be decisive in determining the course of action and set expectations that the process will be followed.

- Facts and data conflict. Fact or data conflict occurs when team members have different perceptions of the facts. Often team members use assumptions to jump to conclusions and become emotionally involved instead of asking for more facts or data. Virtual project managers can help resolve this conflict by asking for additional information and keeping the discussion focused on the data without the emotion.

- Priorities conflict. Priority conflict stems from team members not being clear on project priorities. If priorities are not clear, team members will debate what tasks are most important to work on, and frustration quickly will escalate due to the interdependent nature of work outcomes on a project. Virtual project managers must be diligent in keeping team priorities clear and in consistently communicating the priorities, especially any changes in them, to the team.

- Relationship conflict. Relationship conflict is an awareness of interpersonal differences. This may include personal differences or hostility and annoyance among team members. Since relationship conflict has a negative effect on individual and team performance, virtual project managers must be quick to identify the root cause of the conflict and take measures to begin resolving it. Also, as team members develop a greater awareness of each other through virtual social interaction, relationship conflicts can be minimized and cooperation can more likely be attained.

- Values conflict. Conflicts concerning values are the most difficult to resolve because values are deeply personal. Team members grow up with and hold onto different values based on their backgrounds as well as where they live. This is especially evident when the virtual team is internationally distributed. Virtual project managers cannot expect that a group of people from different national cultures and backgrounds will share the same values. Managers should continually work to help team members stay focused on what they can agree on rather than letting them become polarized.

With all types of conflict, virtual project managers must allow individuals the opportunity to express their differences and allow team members to establish resolution as the first approach. It is not a matter of who has the best ideas or solutions that is important; What is important is finding the solution that will provide the greatest benefit to the team. Doing this requires the establishment of an open team environment and an understanding of the team guidelines for conflict resolution. It may also require coaching on the part of project managers. If the individuals in conflict are not successful in finding a solution among themselves, team leaders will need to intervene (see the box titled “Tips for Resolving Team Conflict”).

Conflict management presents one more argument for taking the opportunity to establish face-to-face contact between members of a virtual team. Evidence shows that on geographically distributed teams, interpersonal bonds are lower, team cohesiveness is lower, members are less satisfied with cross-team interaction, and in general people like each other less than compared to traditional teams.13 These are all factors created by a lack of trust among members of the team and lead to a higher incidence of negative team conflict. In order to trust one another, people must know one another. The surest way to help the geographically distributed team get to know one another is to get them together physically and allow personal relationships to form.

Recognizing the Virtual Team

Providing recognition and rewards on a project can be risky business, even more so for a geographically distributed team. The intent should always be to increase the visibility of the good work being accomplished by the team through recognition.14 However, care has to be taken not to create a reverse effect where team members become demotivated, and trust is compromised.

Co-located teams have traditionally used a variety of approaches to celebrate and recognize project team success ranging from pizza parties, to cash, to movie tickets, to formal organizational awards. However, with virtual project teams, identifying effective and appropriate means to recognize team and individual contributions and successes meaningfully is more difficult. To complicate things further, some recognition approaches that are appropriate in one cultural setting may not be appropriate in another.

Project managers should ensure that team accomplishments are consistently recognized via communication to the sponsor and other key stakeholders. Managers can extend the recognition to the broader organization by tapping into the organization's communications or public relations groups. Project managers should look to accomplish increased public awareness of the team's work and to create a sense of team identity among team members.

Although recognition for virtual teams is harder to administer, many believe it is more important than for co-located teams. It is important to ensure that all involved sites are included in any recognition activities. This is very helpful in overcoming some team members' feelings of isolation. Virtual team members need opportunities to celebrate large and small accomplishments to sustain a high level of team performance.

Rewards are a bit trickier than recognition because they usually are individually based and many times are deemed more valuable because they are tangible. Additionally, rewards are more difficult to provide since team leaders usually cannot offer team members pay raises, bonuses, or vacations.

This requires virtual project managers to be more cautious and creative in providing rewards. See the box titled “Recognizing Virtual Team Members” for some suggestions for recognizing virtual project team members for a job well done.

To provide recognition and rewards effectively, virtual project managers must take stock in the things that they have direct control over and employ them consciously, cautiously, and consistently. They must always look to recognize and reward team accomplishments over individual accomplishments. More on this in Chapter 9.

Leverage Your Leadership Style

All project managers develop their own leadership style based on what they believe works best for them to obtain successful results on projects they manage. It is commonly accepted that most project managers adapt their leadership style based on their project environment. Team leaders who have managed in the traditional team environment and later transitioned to leading teams virtually have had to adjust their leadership style. Accordingly, doing this is necessary to accommodate the lack of or limited face-to-face time for their team members and the need to use electronic means for nearly all team communication and collaboration. Additionally, their leadership style must accommodate teams composed of representatives with other first languages, cultures, and customs.

Due to the fact that more time needs to be devoted to team leadership in the virtual environment as compared to the traditional project team environment, virtual project managers can benefit from a leadership style that emphasizes the understanding and application of behavioral, social, and emotional skills. These skills aid leaders in sharpening awareness, sensitivity, and understanding of their team members. Various texts discuss a number of leadership styles. Some are more commonly used than others. No doubt, leadership styles will continue to evolve to fit the future virtual team environment. The next sections help to determine the type of leadership style needed for different types of project teams.

Transactional Leadership

James MacGregor Burns was one of the first authors to characterize the transactional leadership style. According to the transactional leadership approach, the focus of the team leader is on task accomplishment and achieving project objectives. The leader exhibits behavior that is focused on establishing well-defined roles and responsibilities, team member accountability, consistent follow-up on assignments, and monitoring achievement of project milestones. Also, prompt feedback from team members on problems and other issues is a high priority.15

It is relatively easy for project managers to use a transactional leadership style on traditional projects. The triple constraints foster this style of leadership. In such scenarios, the project schedule is a goal-based motivator and can be used effectively to monitor work completed versus planned and prompt changes in work assignments when needed. On a virtual project, transactional leadership is more challenging for project managers due to the distributed nature of the team and the work. Visibility into the work and accomplishment of tasks can be quite limited, and experienced virtual project managers realize that conversations need to occur at the milestone and deliverables level with focus on team collaboration at critical integration points rather than at the more transactional, task level.

The primary areas of transactional leadership focus on:

- Consistent, standard, and well-prepared communication.

- Established and sustained roles, responsibilities, and expectations with accountability for each task.

- Regular use and communication with progress and status reports.

- Quick attention to risk trending to issues and problems.

- Individual follow-up on tasks and accomplishments.

Transformational Leadership

Bernard M. Bass extended Burns's earlier work, focusing on the transformational leadership style. Under this approach, as the word transformation implies, the leader uses various mechanisms to create a motivating climate for team members. The leader adopts a nurturing style, expressing care for individuals and utilizing ongoing communication and dialogue to identify with the project vision as a means to motivate team members to desired actions. This leadership style focuses significantly on the people side of the project and also contributes to managing and reducing resistance to change, whether the change is to processes, technology, development, or organizational restructuring.16 When team leaders identify with and follow the transformational approach, there is considerable focus on fostering team identity, trust building, encouragement of communication, and collaboration and building the team's working relationships.17 For these reasons, transformational leadership is quite effective for virtual team leadership.

A major point of contrast between transactional and transformational leadership is one of self-interest. Transactional leaders do not often influence beyond self-interest. This is limiting in many ways; for example, it limits individualized consideration, collaborative team building, and collective performance. Transformational leaders motivate and inspire by using more than simple pay incentives; they look to intellectually stimulate their team members, they look to establish meaning and purpose in each member's individual work and the collective work, and they aim to offer individualized consideration to each member of the team.

The primary areas of transformational leadership focus on these areas:

- Establishing team identity

- Establishing trust

- Building team ownership, relationships, and rapport

- Fostering collaboration and integration of work

Situational Leadership

Paul Hershey authored the situational approach to leadership. This approach to leadership is founded on the notion that team leaders need to adopt a leadership approach that fits the situation faced at any given point during the project. Doing this requires considerable flexibility and the ability to adapt quickly during the life of the project. Team leaders must be very sensitive to team members' cultures and be prepared to properly address any confusion and problems that they might present.18

As the name suggests, situational leadership is dependent on a particular set of circumstances. This style takes into account both task activity and team members. The goal is to understand work effort relative to the team members' ability (proven experience, confidence, and capability). For some members of the team, their experience is well established and aligned with their work responsibility for the project. In this situation, virtual project managers will not need to focus on task-level activities. Rather, team leaders should make sure these members are fully engaged, handing off their work appropriately, supporting the work of others, and have opportunities to further hone their skills and learn new ones. Virtual project managers will find team members with the opposite abilities as well. These members may not be as experienced and may be in roles that stretch their capabilities. Virtual project managers will need to spend more time helping these members understand their roles, expectations, and, generally, how to contribute meaningfully without slowing down the project or other team members.

The situational leadership style encourages virtual project managers to adopt an approach that is the best for each team member's experience and capability, relative to the given task of that team member. Doing this requires a high level of flexibility and ability to diagnosis current situations and act accordingly. As the project goes through its life cycle, project managers may very well need to adjust their leadership styles.

When reviewing the leadership styles, it becomes clear that no one style will fit perfectly for all project situations. Given the complex and challenging environment the team faces, virtual project managers need to adopt a leadership approach that, first of all fits their personality and makeup and that second, blends the elements of the leadership styles that enables the leaders to be as effective as possible. For example, Bass, through his work and research, indicated that leaders exhibit simultaneously both transactional and transformational leadership traits when leading teams through the life of a project. Last, it is important to also point out that many elements and traits associated with the transformational leadership style fit nicely with leading across multiple geographic sites in the virtual team environment, given the lack of ongoing human contact necessary for developing and sustaining relationships.

Adding “E” to Leadership

Without deviating from traditional team leadership where one aims to create and drive a project vision, bind organizational components together via a common purpose, and achieve a set of goals, e-leadership is fundamentally different from traditional project team leadership because it takes place in the virtual context and is mediated through the use of technology to communicate and collaborate.

E-leadership (“e” meaning electronic) is related to leadership in the information age, which is characterized by fast development of technology and a global economy where firms compete across national borders seeking out geographies where they can make a profit.20 E-leadership is a descriptive term that includes a significant portion of the leadership accomplished in the virtual environment—it is virtual leadership. The term describes leadership that encompasses electronic technology to achieve a significant portion of the communication, collaboration, and performance of design and development work pertaining to virtual teams. E-leadership can be characterized as a means of socially influencing attitudes, feelings, thoughts, and behaviors through the use of advanced information and communication technology.21

The evolution of virtual team leadership and management toward an e-leadership environment is an important transition. No doubt, leaders of virtual project teams must be proficient in basic project team leadership skills and competencies. However, the ability for team leaders to apply these basic skills effectively through the use of communication and collaboration technologies becomes one of the key challenges and, if accomplished successfully, one of the critical contributors toward achieving a high degree of success in a virtual team's project performance.

Virtual team leaders, therefore, must ensure that members of the team become proficient in the selection, application, and use of available communication and collaboration tools and technologies. (See Chapter 8.) This also includes ensuring that all team members at distributed locations have access to the chosen tools for the project and receive adequate training on the use of the tools.

Skills training typically available for leadership and management does not broadly address the skills and capabilities necessary for achieving higher levels of performance in the e-leadership environment for today and in the future. This, in part, may be because the electronic environment is evolving so quickly that skills and capability development have been unable to catch up. In fact, limiting the definition of the “e” to just electronic technology may not be broad enough for the future. The “e” in the future may be better represented by evolving as being more in tune with the rapidly changing business and virtual environments.22

Becoming an Effective Virtual Team Leader

“I understand the importance of distinguishing the two roles that a project manager has,” explains Jeremy Bouchard. “More important, I underestimated the importance of focusing on building my team leadership skills as much as building my project management skills.”

This realization didn't occur to Bouchard until he began managing virtual projects. “Looking back, I didn't put much thought into leading my co-located teams. The team was formed, we all worked together, we communicated in meetings and hallways, and we collaborated. I had people issues and conflicts to deal with, but those were pretty easy to resolve when everyone was face-to-face and basically trusted one another.

“This was not the case when I took on my first virtual project. I had nothing but people issues right from the beginning, and I was trying brute-force solutions using project management methods.” Fortunately for Bouchard, his manager and mentor recognized the problem quickly and began coaching him in team leadership principles. “Brent started by giving me two John Maxwell books that hammered home team leadership basics. We talked a lot about how to apply those basics in a virtual team setting where communication and leadership is done electronically. He also had me focus hard on establishing team trust. I now realize that trust is the foundation of all team leadership principles.”

However, there is still more learning and work to be done. “I'm still working on adjusting my leadership style to fit particular situations that arise. I'm currently focusing my learning on recognizing when a situation requires a different style.”

Assessing Virtual Team Performance

The virtual project team performance assessment is intended to be used by an organization to focus on a specific project. The primary benefit in using this assessment is tracking virtual project team performance over time to assess the continual growth in performance. This assessment can also be used at the completion of virtual projects. The results from the assessment are intended to serve as the basis for future organizational actions for virtual project team improvements.

The assessment works best when a team remains together for more than one project in order to minimize the disruptions created by losing personnel and having to re-form and rebuild teams. To broaden the breadth of understanding on the overall team performance, managers of an organization may choose to have a wider vested audience complete the assessment, including the virtual project manager, team members, project sponsor, the senior management team, and other key stakeholders.

Virtual Project Team Performance Assessment

Date of Assessment: __________

Virtual Project Team Code Name: ________________________________

Virtual Project Manager Name: __________________________________

Project Start Date: _____________

Planned Completion Date: _____________

Team Size: ________

Assessment Completed by: _____________________________________

Confidential Assessment: ______ Yes, confidential

______ No, not confidential

| Assessment Item | Yes or No | Notes for All No Responses |

| All team members were aligned to the project mission and objectives. | ||

| There are proven examples of clarity in project roles and responsibilities. | ||

| Project team norms and guidelines were in place, understood, and used. | ||

| High levels of individual motivation and sense of purpose were achieved. | ||

| Project planning was successfully achieved. | ||

| Effective project monitoring was in place and utilized effectively by the project manager. | ||

| Project schedules and milestones were achieved by the team. | ||

| Project budgeting and cost controls were successfully managed by the team. | ||

| The project team identified and managed risk properly. | ||

| A high degree of trust among the project team was evident and observable. | ||

| There are proven examples of awareness of team diversity and cultural management. | ||

| There are proven examples of effective conflict management. | ||

| Effective project leadership capabilities (participative, empathy, supportive, mentoring, motivator, provide feedback) were exhibited by the project manager. | ||

| The project manager dealt with resolving problems and removing barriers to team progress. | ||

| The team proactively and positively managed project changes. | ||

| The team communicated and collaborated effectively across all geographic locations. | ||

| The team successfully managed and influenced the virtual stakeholders. | ||

| Customer and client needs were effectively addressed. | ||

| Senior leaders and other stakeholders assessed the project team as achieving the project goals. | ||

| Lessons learned and retrospective activities were completed and the findings applied and shared with other projects. | ||

| Findings, Key Thoughts, and Recommendations | ||