Introduction

Have Fun, Start Now

We’re going to start this book with a quick thought experiment. Suppose you have a teenaged child. (If you actually do, so much the better.) Surveys show that the typical teen has about five hours of leisure time each weekday. How would you like your teenager to spend those five hours? To provide a little structure, I’ll give you six categories of activities among which the time could be allocated. (Note that with six categories, equal time to each activity is fifty minutes.)

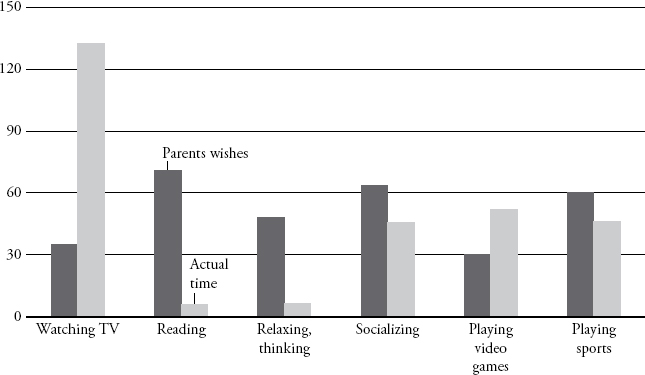

Have your answers? You can compare them to the results of a survey I conducted of three hundred American adults. I’ve also depicted the actual number of minutes that teens spend on each activity, according to the national American Time Use Survey (figure I.1). For reading, the hoped-for amount among my respondents was 75 minutes. The actual time American teenagers spend reading is 6 minutes.

Figure I.1. Wishes versus reality in teenagers’ leisure time. Darker bars show how our survey respondents hoped teenagers would spend their leisure time. Lighter bars show actual leisure time spent, according to the American Time Use Survey.

Source: © Daniel Willingham.

The purpose of this book is simple. Parents want kids to read. Most kids don’t. What can parents do about that?

Of course, some kids do grow up as readers. The numbers in figure I.1 are a little deceptive because they are averages; it’s not that each teenager goes home from school, reads for six minutes, and then puts the book down. Most kids don’t read at all, and a few read quite a lot. Can the parents of those readers provide us with any guidance?

In my experience, most of those parents have little idea of how their kids ended up as readers. A conversation I had with an editor at the New York Times is typical. I mentioned I was working on this book, and he told me that his eighth grader was the kind of kid who had to be reminded to step outside every now and then to get a little fresh air, so devoted was she to whatever book she was reading. When I asked what he and his wife had done to foster this passion, he laughed heartily and said, “Not a damn thing.”

Now, almost certainly he has done things that prompted his child to read. He’s a newspaper editor, for crying out loud. He probably read to his daughter when she was little, his house is probably filled with books, and so on. I’m sure he’d agree. What I think he meant by “not a damn thing” was, “We didn’t plan it.” Parents who raise readers don’t do things that look especially academic. They aren’t tiger parents, breaking out flash cards when their baby turns twelve months and starting handwriting drills at twenty-four months. Such measures are not only unnecessary, they would undercut a crucial positive message that these parents consistently send: reading brings pleasure. Most of what I suggest in this book is in the spirit of emulating nontiger parents, and I encapsulate it in this simple principle: Have fun.

Another principle guides the advice in this book: Start now. Parents tend to think about the different aspects of reading as each comes up in school. They think about decoding (learning the sounds that letters make) in kindergarten, when it’s first taught. Parents don’t think about reading comprehension at that point, because it’s not emphasized in kindergarten. If kids can accurately say aloud the words on the page, they are “reading.” But by around the fourth grade, most kids decode pretty well, and suddenly the expectation for comprehension ratchets up. At the same time, the material they are asked to read gets more complex. The result is that some kids who learned to decode just fine have trouble when they hit the higher comprehension demands in fourth grade. And that’s when their parents start to wonder how they can support reading comprehension.

Parents often don’t think about reading motivation until middle school. Almost all children like to read in the early elementary years. They like it at school, and they like it at home. But research shows that their attitudes toward reading get more negative with each passing year. It’s easy for parents to overlook this change because children’s lives get so much busier as they move through elementary school; they spend more time with friends, perhaps they take up an instrument or sport, and so on. When puberty hits, their interest in reading really bottoms out. A parent now realizes that her child never willingly reads and starts to think about how to motivate reading.

At these three crisis points that prompt parents to think about reading, we see the three footings for a reading foundation. If you want to raise a reader, your child must decode easily, comprehend what he reads, and be motivated to read.

How, then, to ensure that these three desiderata are in place?

Obviously, hoping for the best and reacting if a problem becomes manifest is not the best strategy. It’s easier to avoid problems than to correct them. But reading presents a peculiar challenge because experiences that seem unimportant are actually crucial to building knowledge that will aid reading. Even stranger, this knowledge may be acquired months or even years before it’s needed. It lies dormant until the child hits the right stage of reading development, and then abruptly it becomes relevant. That’s why the second guiding principle of this book is, Start now. “Start now” means attending to decoding, comprehension, and motivation early in life—as early as infancy. But it also means that action to support your child’s reading never comes too late, even if your child is older and you’ve done nothing until now. Just start.

These three foundations also provide an organizing principle for this book. In the first chapter, you’ll get some of the science of reading under your belt. How do children learn to decode? What is the mechanism by which they understand what they read, or don’t? And why are some children motivated to read, whereas others are not? The remainder of the book is separated into three parts, divided by age: birth through preschool, kindergarten through second grade, and third grade and beyond. Within each part, separate chapters are devoted to how you can support decoding, comprehension, and motivation at that age. I will discuss not only what you can do at home, but what you can expect will be happening in your child’s classroom.

That said, if you want to raise a reader, you should not rely much on your child’s school. That’s not a criticism of schools but rather a reflection of what this enterprise is all about. Let me put it this way. You’ve got this book in your hands, so I’m assuming you’re at least somewhat interested in your child being a leisure reader. Why?

Some answers to this question are grounded in practical concerns. Reading during your leisure time makes you smarter. Leisure readers grow up to get better jobs and make more money. Readers are better informed about current events, and so make better citizens.

These motives are not unreasonable, but they are not my motives. If I found out tomorrow that the research was flawed and that reading doesn’t makes you smarter, I would still want my kids to read. I want them to read because I think reading offers experiences otherwise unavailable. There are other ways to learn, other ways to empathize with our fellow human beings, other ways to appreciate beauty; but the texture of these experiences is different when we read. I want my children to experience it. Thus, for me, reading is a value. It’s a value—like loving my country or revering honesty. It’s this status as a value that prompts to me to say, “Don’t expect the schools to do the job for you.”

I’m reminded of a parent I know who was dismayed when his child announced that she was marrying someone of a different faith. Her father asked how the children would be raised, and she made it plain she was not much concerned one way or the other. Although he and his wife had not made religious identity much of a priority at home, he was nevertheless surprised and hurt by his daughter’s decision. “I can’t understand it,” he told me. “We sent her to Sunday school every week.” He had subcontracted the development of this core value.

If you want your child to value reading, schools can help, but you, the parent, have the greater influence and bear the greater responsibility. You can’t just talk about what a good idea reading is. Your child needs to observe that reading matters to you, that you live like a reader. Raising Kids Who Read aims to show you in some detail how to do that and with a sensibility that embodies two principles: we have fun, and we start now.

Notes

“makes you smarter”: Ritchie, Bates, and Plomin (2014).

“better jobs and make more money”: Card (1999); Moffitt and Wartella (1991).

“maker better citizens”: Bennett, Rhine, and Flickinger (2000).