Chapter 6

Banking Knowledge for the Future

When a child is learning to decode, we obviously expect little by way of reading comprehension. But by grade 3 or so, we start to expect that students can comprehend longer, more complex texts and that they will branch out into reading texts from genres other than stories. At home and at school, they may be exposed to letters, newspaper articles, and expository text like encyclopedia entries. Kids are still not asked to work with the texts in a serious way (e.g., to use them in research)—that won’t come until the upper elementary years. But once children can decode reliably, the expectations for comprehension begin to increase.

Understanding Longer Texts

We begin by considering what’s required to understand longer texts. This entails not just connecting sentences, as I discussed in chapter 1, but the way that readers connect many ideas into something bigger. After that, we’ll consider how schools can support the development of this more challenging comprehension task.

Capturing Big Ideas

Reading comprehension begins when the reader extracts ideas from the sentences he reads. Then he connects ideas that are about the same thing (“The tissues are on the desk. The tissues are white.”) or ideas that are causally related (“The stranger tapped on the window. The dog barked.”). The result of making these connections is a network of related ideas, analogous to a social network. Imagine a web of connections that vary in strength.

That’s a good start at explaining reading comprehension, but it’s not enough. Consider this text:

If understanding were merely a matter of connecting ideas into a network—about-the-same-thing connections and causal connections—this passage would not seem strange. But it does, and it’s not hard to describe why. There’s no big picture. Each idea can be connected to another, but there’s no overall idea of what the paragraph is about.

Somehow readers need to represent in memory the big picture of what they read. One of the seminal experiments on how readers meet this challenge used very brief text similar to this one: “Two birds sat on a branch. An open birdcage sat on the ground beneath them.” Now suppose I asked you, “Was the branch above the birdcage?” If you had nothing but the specific sentences in your memory, you could answer that question by combining what you were told with some logical inferences, like this:

Our intuition tells us that we don’t answer the question that way, and research supports that intuition. But what choice is there but to answer the question based on what you read?

The alternative is that you create a representation of the whole situation the sentences describe. It’s called, appropriately enough, the situation model. A situation model helps you keep track of many related ideas (e.g., the relative positions of the birds, branch, and birdcage) independent of the particular sentences used to describe those ideas. The situation model could be verbal, but it doesn’t have to be (figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1. Nonverbal situation model. Visual mental images are a way to represent complex relationships without being tied to one description. You could consult this mental image and just as easily verify “birdcage is under branch” or “branch is over birdcage” however their positions were described in what you read.

Source: © Matthew Cole—Fotolia.com.

Background Knowledge Revisited

You’ll recall that background knowledge was needed to make the causal connections among sentences. The same is true of the situation model. Background knowledge both influences your ability to create the situation model in the first place and colors your understanding of a text’s overall message. And as was true for the background knowledge that allows you to connect sentences, writers omit information needed to create the situation model on the assumption that readers already know it. For example, have a look at this text:

Some knowledge is required to interpret individual sentences and connect them (e.g., the meaning of “hour hand”), and the writer doesn’t bother to provide that knowledge. But even if you have all of the knowledge required to connect the sentences, your situation model would include other facts from your background knowledge like these:

- That it’s unusual to use a tool designed for one purpose for an altogether different purpose

- Why you might need a compass in a situation where you don’t have one

- That ad hoc tools like this are often pretty rough in serving their function, but if you’re lost, rough information about direction is much better than none at all

That background information highlights the big picture for you. It’s vital to appreciating what makes this text useful and interesting. Now consider this parallel text:

Although this passage, like the previous one, describes how to find something, I’m guessing that reading it felt different. It’s not that you don’t understand it. The sentences make sense, and how they relate to one another makes sense. What’s missing is some sense of deeper understanding. That’s because a well-developed situation model would have other information from your background knowledge. You probably don’t know why you’d want to know where parts of the brain are simply by looking at the skull. And while you might guess that this method of localization is imperfect (just like the watch-compass technique), it’s harder to judge whether this rough information would really be better than none at all.

It’s hard to appreciate just what a difference background knowledge makes to your situation model and thus to the experience of reading comprehension, so here’s one more example:

I’m wagering that you had little trouble reading this paragraph with good comprehension. But suppose I had told you, “By the way, the character, Carol Harris? That’s actually Helen Keller. They just changed her name for the story.” That alters your understanding. For example, you interpret statements about her wildness and violence in light of what you know about Helen Keller’s blindness and deafness, and the frustration and despair it might have caused.

Imagine a person reading this paragraph without knowing anything about Helen Keller. This reader would “comprehend” it as you did when the name Carol Harris was used. All the sentences make sense, and the paragraph as a whole hangs together. And yet an important aspect of meaning is absent. Even if you have sufficient knowledge to connect the sentences, there is usually a still deeper level of comprehension that can be reached. That’s the situation model: you integrate the ideas in the text not just into an overall big picture; that big picture is colored by other relevant knowledge from your memory.

What’s Happening at School

Although the demands for comprehension are modest in kindergarten and first grade (because the focus is on learning to decode), they increase rapidly thereafter. As I’ve emphasized, background knowledge is vital to support comprehension, so children should be acquiring knowledge during those early elementary years. But there are obstacles to this learning.

Slowly Increasing Demands on Comprehension

Developing the situation model becomes increasingly important as kids move through the elementary years, for two reasons. First, texts become more complex, meaning we place greater expectations on children to coordinate meanings from the beginning to the end. For example in the Common Core State Standards, the recommended texts for first graders include books like Little Bear and Frog and Toad Together, and others that feature large illustrations on each page with modest amounts of text. But the second- and third-grade band of texts includes Charlotte’s Web and Sarah, Plain and Tall—much longer, much more involved texts. The reader must create larger chunks of meaning, and so the situation model will be more complicated.

Students must also coordinate meanings over multiple texts; they apply knowledge from prior texts when they read something new. Suppose a child is passionate about butterflies. He reads books about their behavior, he has identification guides, and so on. The situation model of each text doesn’t lie in memory, totally insulated from the situation model of other texts. What he knows from these different sources ought to get brewed together. As kids move through school, we increasingly expect that they will remember and apply things they have learned before to new reading.

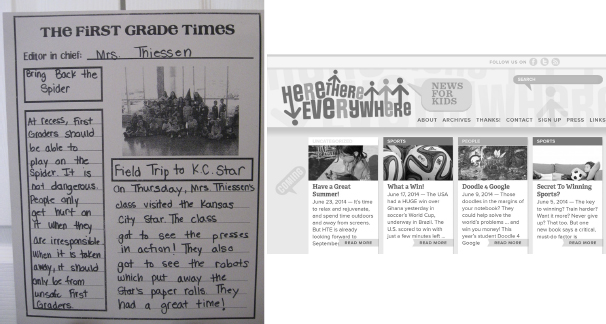

Second, students start to encounter a greater variety of genres. At the start of school, most of the texts children read or hear are stories. Thus, most kids come to understand typical Western narrative structure pretty well: there is a main character who has a goal, there is an obstacle preventing the character from reaching the goal, the character has some adventures and complications in pursuing the goal, and then at the end of the story, the character reaches the goal. Knowing that basic structure helps the child’s comprehension. As she reads, each new character and event she encounters can be fit into that familiar story structure. When children begin to read other genres of text, however, they no longer have that support to comprehension; they must learn the conventions of other genres (figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. Learning new genres. “Literacy” means stories until the early elementary years. At that point children start to encounter new genres. Teachers might have kids publish their own newspaper as a writing project, or they may encourage children to read age-appropriate news stories on one of the many websites designed for kids. “Here, There, Everywhere” was created by a former Today Show producer who wanted to bring the news to young children.

Source: © Alexandra Thiessen. Here, There, Everywhere website screen shot reproduced by permission.

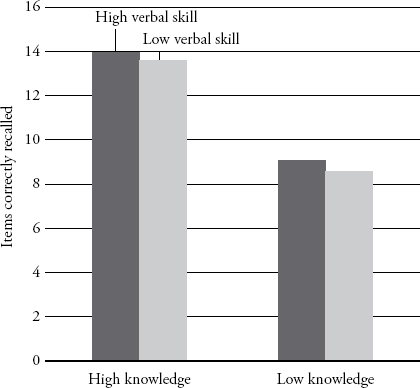

A number of studies in the past thirty years show that knowledge of specific topics is a powerful aid to comprehension. In one, elementary school children took standardized tests of their verbal comprehension and reasoning skills. They were also tested on their knowledge of soccer. The experimenters separated the students into four groups based on their soccer knowledge (high or low) and their general verbal skills (high or low). Then students read a story about soccer, and experimenters measured their comprehension and recall (figure 6.3).

Figure 6.3. Knowledge and verbal skill. The graph shows how much readers remembered of a text about soccer. Kids identified as having “high verbal skills” remembered a bit more than kids with “low verbal skills” (compare the dark and light bars). But that effect is tiny compared to the effect of knowledge of soccer.

Source: “Domain specific knowledge and memory performance: A comparison of high- and low-aptitude children” by W. Schneider, J. Körkel, & F. E. Weinert, in Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 306–312. Data are from Table 2, p. 309. © American Psychological Association, 1989.

In this experiment, “verbal skill” doesn’t mean much compared to knowledge. Knowing the kinds of things that generally happen in a soccer game and the sequence in which they are likely to happen provides the same sort of framework that knowledge of stories would.

Here we see still another reason to ensure that students have broad background knowledge if our goal is that they be able to read most any text written for the layperson. Knowledge is important not just for connecting sentences; it makes a separate contribution to understanding longer, more challenging texts. How can we ensure that kids learn what they need to know in the early elementary years?

The Importance of Acquiring Background Knowledge

Research shows that reading depends on broad knowledge of all subjects: history, civics, science, mathematics, literature, drama, music, and so on. Furthermore, it makes sense that subject matter knowledge be sequenced. It’s commonly appreciated that mathematical concepts build on one another, and they are easier to learn if they are sequenced properly. The same is true of other subjects. It’s easier to understand why the last remnants of European colonialism crumbled in the 1950s if you know something about World War II. It’s easier to understand World War II if you know something about the Great Depression. And so on. So the content that students will learn in the earliest grades is hugely important. It’s the bedrock of everything that is to come (figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4. First European colonists. Typically children learn about the arrival of the first European colonists (here depicted on a panel from the US Capitol Rotunda) in their early elementary years But wouldn’t it be easier to appreciate the arrival of the colonists if you first studied the Native Americans who were already here? And wouldn’t it be easier to understand their lives and culture if you had already had a unit about farming? And wouldn’t it be easier to understand farming if you had first studied plants?

Still, talk of “academic content” in early grades makes some adults anxious. So let me address some of the more common concerns.

Can’t Kids Just Be Kids?

When people hear “academic content in prekindergarten,” they sometimes jump to the conclusion that it means studying long lists of facts and that the mode of teaching will be a lot of teacher talk, followed by practice worksheets, followed by tests. After all, that’s how older kids are often taught academic content. But if you’ve read this far, you know that drilling and testing are not my style. I’m thinking of activities like read-alouds, projects, independent work with materials, field trips, video, and, yes, listening to the teacher, visitors, and one another.

Ideally, when kids get a bit older, they learn rich content as they practice reading. Unfortunately, that’s not likely, as the commonly available basal readers tend not to be heavy on ideas and tend not to have a systematic sequence to whatever ideas they do contain. So schools and districts need to pay special attention to the need for knowledge. They won’t get it from most off-the-shelf products.

Is This Developmentally Appropriate?

Another take on the “can’t kids just be kids” argument is to suggest that kindergarten children cannot learn certain concepts. The usual term is that such content is “developmentally inappropriate.” In other words, there is a predictable sequence to the development of the mind, and six-year-olds are cognitively incapable of understanding certain concepts. This concern was voiced strongly in 2013 when New York State posted part of a first-grade curriculum module on early civilizations that included vocabulary terms like “sarcophagus” and “cuneiform.”

A number of bloggers took to the web, suggesting that such a lesson would be developmentally inappropriate. How can children be expected to understand anything about a five-thousand-year-old Mesopotamian civilization when they (1) have no concept of five thousand years; (2) have no concept of where countries are located on a globe (e.g., “modern-day Iraq” will be meaningless to them), and (3) don’t know what their own civilization is, much less someone else’s?

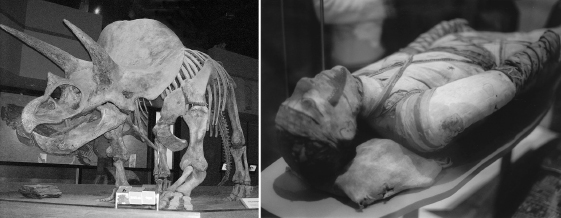

My reply will necessarily be brief, but here goes. Drawing broad conclusions about what children can and can’t understand doesn’t work because their understanding depends on the task. I’ve heard people say “six-year-olds can’t understand abstractions.” But learning to use the word “dog” (or any other category label) is an abstraction. The idea that “dog” applies not just to particular objects but to any instance of a class of objects (many of which look dissimilar) is an abstraction. Whether a particular abstraction can be learned depends more on what the child already knows and less on some biologically predetermined course of development, linked to the child’s age (figure 6.5).

Figure 6.5. Old, dead subjects. The idea that children will be baffled and bored learning about things that are unfamiliar and cannot be physically encountered seems belied by the fascination many children have for dinosaurs and ancient Egypt.

Source: Dinosaur © Redvodka; derivative work, original by Mathnight, via Flickr: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Dinosaur#mediaviewer/File:TriceratopsTyrrellMuseum1.jpg. Mummy © Klafubra, via Flickr: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Mummy#mediaviewer/File:Mummy_at_British_Museum.jpg.

“Developmental appropriateness” rests on an assumption about the mind that is probably wrong. It suggests that the mind develops in discrete stages, where one month the child’s mind works one way and then a few months later it works another way. That’s the idea behind “they are incapable of learning that, but in a year most will be ready.” It’s more accurate to describe the learning of new ideas as coming in fits and starts; the child understands in one situation but not another. The child shows understanding on Tuesday and then doesn’t in the identical situation on Thursday. So it will be with children gaining some appreciation of what it means for a civilization to have existed five thousand years ago. If you wait until you’re certain they can understand it, you will wait too long. And you will find that students from wealthy homes are more likely to have been exposed to ideas that help them understand it earlier.

I can’t resist providing one example from the classroom of my wife, an early elementary teacher. She teaches seven-year-olds about the creation of the universe and the origins of humankind. She reads a description of the big bang; the subsequent formation of galaxies, stars, and planets; the formation of the earth; the coming of life; the development of other species; and finally the development of humans. (The description is about three pages long.) As she’s reading, an assistant unrolls a strip of black felt. It’s a foot wide and forty-five feet long. The last sentence describes humankind emerging, and that’s when the last of the felt is exposed—and it’s covered by a thin red ribbon. The black felt represents the time since the big bang, and the red ribbon is the amount of time that humankind has existed. So after seeing that, do seven-year-olds have a perfect conceptual understanding of vast time? Of course not. But they are closer than they were.

Making Time

A more serious concern is time. I’m suggesting that more attention be paid to content knowledge, and attention means time. There’s less instructional time in early elementary classrooms because students take longer to transition from one activity to another. And once a teacher has done some phonics work, some read-alouds, and some writing, how much time is left in the day? Well, in a couple of studies from the early 2000s, researchers observed several hundred first- and third-grade classrooms across the United States and wrote down what happened (figure 6.6).

Figure 6.6. Time in classrooms. Time spent on different subjects in first grade (darker bars) and third grade (lighter bars). The numbers add to greater than 100 percent because some lessons combined more than one subject.

Source: First-grade data from “The relation of global first-grade classroom environment to structural classroom features and teacher and student behaviors” by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, & Early Child Care Research Network. Elementary School Journal, 102, 367–387. Data from Table 2, p. 376. © The University of Chicago Press, 2002. Third-grade data from “A day in third grade: A large-scale study of classroom quality and teacher and student behavior” by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, & Early Child Care Research Network. Elementary School Journal, 105, 305–323. Data from Table 2, p. 314. © The University of Chicago Press, 2005.

As you can see, language arts and math account for nearly all instructional time. Science and social studies are neglected.a So in answer to the objection that “there’s no time to add content,” I answer, “We have to make time.” And it’s pretty obvious what to cut, at least looking at these averages. We have to curtail language arts activities that we think offer students the least benefit and replace them with science, history, drama, civics, and so on. If we don’t, we can expect a cost to reading comprehension in later grades.

What to Do at Home

The last section ended with a pretty sobering set of statistics about time spent on content knowledge in schools. In chapter 5, I encouraged you to count on your child’s teacher to get him reading, but when it comes to knowledge building, you can’t exhort the schools and hope for the best. This work will fall to you. In chapter 3, I described desirable practices meant to spark interest in knowledge—those are still desirable. But as kids get older, some of the activities take a different shape.

Talking

You still want to ask your child questions, of course, but as they grow, you can expect them to provide longer answers and you can pose more open-ended questions. The most natural thing to ask about is what happened at school. You’ll get social stuff in response—what happened at recess or at lunch. That’s fine, but it’s nice to know about the rest of the day (which also gives you the chance to express interest in what he learned—not just because he’s the one learning it, but because you find the topic itself interesting). “What else happened?” will likely draw a blank look. The best strategy is to pose a more specific question. For example, if you know that the class writes in response to a teacher-generated prompt for five minutes each day, ask, “What was the writing prompt today?” So that means it pays to know something about the specifics of what’s happening in the classroom, information you might glean from a classroom newsletter or website or from back-to-school night. Or, better, talk to the teacher about it.

I think children learn a couple of things from telling you about their day. They get practice in telling a story, in putting their thoughts together and relating what happened in a way that has a beginning, middle, and end. So even if the playground drama of first-grade alliances is not what you meant when you asked what happened at school, bear in mind that your child is getting some benefit from telling you this story. And she’ll get even more if you pay attention, ask questions, and feign confusion if she’s not telling the story in a logical sequence.

In addition to providing feedback about your child’s storytelling, show him how it’s done. Tell your own stories. This is a marvelous age at which children understand that you were once young, and they generally find it fascinating to hear about your life. Hearing your stories provides a model, and there is often more background information in them than you would think. My father told me countless stories about his boyhood in Rome, Georgia, in the 1930s—stories about games of capture the flag in the alleyways among downtown buildings; stories of lying, sleepless, on sweat-soaked sheets on July nights, waiting for the brief, relieving breeze brought by the oscillating fan; and the story that became the town sensation one summer: a teen dared a soda jerk holding a butcher knife to chop off his finger, certain that the soda jerk would chicken out, whereupon the soda jerk, certain that the teen would pull his hand away at the last moment, chopped off the finger. In addition to bringing me closer to my father and learning something about how to weave a good narrative, those stories taught me what alleyways, oscillating fans, and soda jerks are.

Reading

Naturally you should continue reading to your child. Don’t quit because your child can read or because your child now reads to you. Remember, when he was little, you read to you him not because he couldn’t do it himself but because it was a pleasurable way to spend time together. That hasn’t changed. And given that learning to decode inevitably entails some struggle, read-alouds are the time to remind him that reading brings joy. Then, too, as your child grows in ability to follow and appreciate more complex narrative, there’s a greater chance to introduce books that you enjoy.

In chapter 3 I suggested that read-alouds for young children could include nonfiction. Some children immediately take to fact-filled books—one seven-year-old told me in a grave voice, “I like books with information”—but others don’t. This is a good age to give nonfiction another try, because your child has probably developed some personal interest that can guide your selection of a nonfiction book: soccer, bugs, ballet, whatever. There are terrific books that are still loaded with pictures like those targeted to younger kids, but with richer text.

Certain topics dominate nonfiction at this age: animals, weather, historical subjects. Another idea is to try a picture-rich book related to a game that your child loves, even if the text is beyond her. If she loves Barbie, why not a book on the history of Barbie fashions? If your child loves gross-out toys, how about Nick Arnold’s Disgusting Digestion? The Hexbug enthusiast might enjoy the Eyewitness: Robots book. If you’re at the library and these ideas elicit little interest from your child, get a book on the subject that your child hasn’t yet seen and drop it in his bathroom book basket without mentioning it. You never know. (Or if your kids are like mine, pretend the book is yours and leave it in your bathroom book basket, which will make it more attractive.)

Playing

On the subject of games, some board games are useful sources of background knowledge. I’m not talking about “games” that are really drill sessions in phonics or number facts dressed up to look like games. These merit the disdainful descriptor “chocolate-covered broccoli.” But some games are genuine fun and require knowledge as part of their play: The Scrambled States of America for US geography, for example, Apples to Apples Junior for vocabulary, and Scrabble Junior for spelling. I especially like games that don’t demand knowledge to play, but expose kids to it incidentally. Zeus on the Loose uses Greek gods as characters. In Masterpiece the point is to collect valuable art, and the works depicted are classics of the Western canon. 20th Century Time Travel is a rummy-like card game, with history facts on the cards, not unlike the classic card game Authors. You do have to exercise some caution, as many games claim to be educational. If there are dice, then it’s a counting game. If it requires sorting, then kids are finding patterns.

Home-grown word games can still be good fun, but are likely to change as kids get older. They’ve probably outgrown phonological awareness rhyme games, but now know enough words for vocabulary games. My kids like to keep it simple: I say a word and they are to guess the synonym I am thinking of. Remember the old game show Password? That’s basically it. Sometimes they give the clue and I guess, but the other arrangement is easier for them; words that are hard to bring to mind are easily recognized when someone else says them. More challenging is the two-word version. I think of two words that rhyme, and then provide a descriptive phrase, for example, “What do you call it when your trousers do the waltz?” A pants dance.

My wife plays another version of the synonym game with the kids in her class that they have dubbed “Say It Again, Sam.” It can be played by kids of varying ages. Someone starts by saying any sentence, for example, “This cupcake has pink frosting.” Each player then rephrases the original sentence. A five-year-old might say, “This small cake has pink frosting.” A ten-year-old might be more ambitious in trying to avoid repetition of the original and say, “The small cake before me is covered in a mixture of sugar and butter that looks light red.” Kids can get surprisingly creative (and surprisingly funny) when they get absorbed in this game.

Gaining Independence

As your child learns to decode and gains fluency and confidence, you’ll want to start teaching her to do on her own things that you have, until now, done for her. Indeed, she’ll want to do those things herself. When a word needs a sharper definition or a fact is in dispute, you have made a habit of finding the needed information in a dictionary or encyclopedia. Now is a good time to buy your child her own kid-friendly reference books. But remember, it’s not obvious to the neophyte how to use these books. She’ll need your guidance.

These fledgling research skills can also be practiced when you plan a family trip. Going to Disneyworld? Let’s get out the globe and find Orlando. How can we find out what the weather will be like so we can pack the right clothing? Why is it so warm in Orlando if it’s so cold here? And so on. Even if you’re taking just a day trip, find your destination on a map and read up a bit about where you’re going (figure 6.7).

Figure 6.7. Buy a globe. Globes seem old-fashioned in the age of the web, and they are not cheap—a decent one will set you back fifty dollars or more. But I think they are a good investment. There is no substitute for a globe to give your child a sense of geographic distance. And your child will make surprising discoveries (the United States isn’t bigger? Lichtenstein is a country?) for years.

Source: © Christian Fischer—Fotolia.

Another sure sign of your child’s independence: she’s ready for her own magazine subscription. That offers a triple thrill: (1) there are a lot of terrific magazines for kids, (2) having her own subscription is a sign of being more grown up, and (3) everybody loves getting mail. Check out Ladybug, Click, Highlights, National Geographic Kids, Ranger Rick (and Ranger Rick, Jr.), Kind News (primary), Mocomi, Your Big Backyard, New Moon, Our Little Earth, Nickelodeon, Sports Illustrated Kids, American Girl, Stone Soup, and Time for Kids.

Magazines not only build knowledge, they will, we hope, keep kids motivated to read. In the next chapter we’ll consider other measures to maintain the motivation of early elementary readers.

Notes

“‘Two birds sat on a branch. An open birdcage sat beneath them.’”: Barclay, Bransford, Franks, McCarrell, and Nitsch (1974).

The Carol Harris story is from Sulin and Dooling (1974).

“tend not to be heavy on ideas”: Duke (2000); Moss (2008); Pentimonti, Zucker, Justice, and Kaderavek (2010).

“My reply will necessarily be brief, but here goes.”: For a review, see Willingham (2008).

“a couple of studies from the early 2000s”: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Early Child Care Research Network (2002, 2005).

“and recent smaller-scale studies support this general conclusion”: Baniflower et al. (2013); Claessens, Engel, and Curran (2013).