Chapter 8

Reading with Fluency

Your child is now a third grader or older. Assuming all has gone more or less to plan, doesn’t he know how to decode by this age? He does, but there are actually two processes of decoding, not one. The first process, more easily observed, develops in kindergarten. The second process, clandestine, develops slowly and is still being fine-tuned as late as high school. It’s this second process that supports fluency, and it’s just as important as the first process, for it enables your child to read quickly and effortlessly. In this chapter, we look at ways to ensure it develops in full.

The Second Type of Decoding: Reading via Spelling

So far I have described decoding as the process by which the reader turns printed letters into sound. I said beginning readers don’t recognize words by their appearance—that is, by their spelling. But we can think of cases where it would seem that spelling must count for something. If reading depended only on sound, how could you differentiate homophones like “knight” and “night”? You could argue that you use sound to read the word, but then you use the meaning of the sentence to figure out whether “knight” or “night” is meant. Thus, when you read the line from Sandburg’s poem “Night from a railroad car window is a great, dark, soft thing,” you know the poet is talking about the evening because a mounted soldier in armor is unlikely to be seen from a railroad car. But if I use surrounding context to disambiguate meaning, then it shouldn’t be noticeable if I encounter the phrase, “My favorite Beatles album is A Hard Day’s Knight” or a reference to a strongman performing “feets of strength.” Spelling, it seems, does matter to reading.

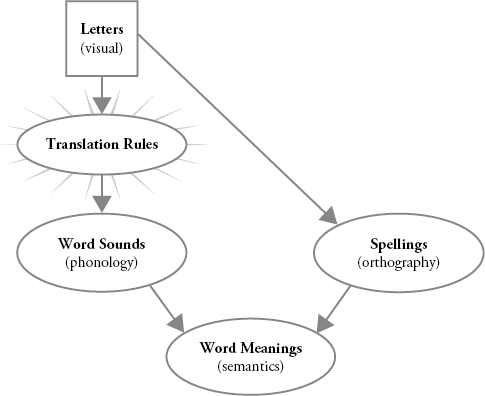

It turns out that experienced readers have two ways of accessing word meaning from print. The first is the way I’ve already described: you use a set of rules to translate the printed letters to sound, and then more or less say the word to yourself. The sound of the word is connected to its meaning. The second method uses the spelling: you directly match letters on the page to your knowledge of how words are spelled. That spelling knowledge is also connected to the meaning (figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1. Two reading pathways. There are two ways to get from print on the page to meaning in your mind. A complete diagram would include other connections—expecting a particular meaning influences what you hear, for example—but we’ll keep things simple.

Source: © Daniel Willingham.

Fluency and Attention

The spelling knowledge you use to read is a bit like your ability to recognize objects in that you don’t need to consciously consider what things look like to recognize them. You don’t say to yourself, “Hmm, let’s see . . . there’s a paw, and that looks sort of like a muzzle, and that thing is probably a tail . . . this is shaping up to be a dog.” You just see a dog. And like your ability to recognize objects, your ability to visually recognize words includes being able to recognize pieces; even though you seldom encounter a dog’s paw in isolation, you would know that it’s a paw. Likewise, spelling representations in the mind can identify clumps of letters that you frequently see, even though they are typically part of a word. That’s why “fage” looks more like a word than “fajy.” The letter “j” is seldom followed by the letter “y,” but “ge” is a frequently encountered clump of letters.

Reading by spelling does allow you to differentiate homophones like “knight” and “night,” but there’s a much more important advantage: it’s faster and easier to use than the translation rules. Translation rules demand a lot of attention (symbolized by the radiating lines in figure 8.1). Just as the beginner driving a car must consciously think about how far to turn the steering wheel to change lanes, how closely he’s following the car ahead, and so on, the attention of the beginning reader is absorbed by sounding words out: “Let’s see, ‘o’ usually sounds like AW, but when there are two of them, ‘oo,’ they make a different sound . . . what was it again?” That makes it hard to focus on understanding the meaning of what she’s reading.

With experience, all of that thinking the driver had to do seems to disappear. Driving becomes automatic, and you can stay in your lane and keep the car at the correct speed without really thinking about it. That leaves your attention free to do something else: daydream or talk with a passenger, for example. In the same way, practice in reading reduces the attentional demand imposed by translation rules—reduces, but never completely eliminates. You can feel the small attentional cost yourself when you encounter an unfamiliar word and sound it out; for a short one like “fey,” the cost may be barely noticeable, but make the word long so that it really taxes the translation process, and you notice that your reading slows down. Try “triskaidekaphobia.”

In contrast, using word spellings to read requires very little attention, if any. You just see it in the same way you just see and recognize a dog. As your child gains reading experience, there is a larger and larger set of words that he can read using the spelling, and so his reading becomes faster, smoother, and more accurate. That’s called fluency.

Fluency and Prosody

It’s easy to see that fluency would aid comprehension. With sound translation demanding less attention, more attention can be paid to meaning. There’s a second, somewhat more subtle way that fluency helps comprehension. Fluency actually ends up helping comprehension through sound. Here’s how.

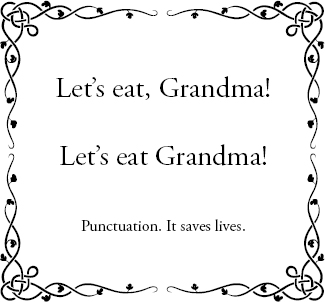

I mentioned prosody in chapter 2 when discussing “motherese.” You’ll recall that it’s the sort of melody of speech. We don’t speak in a monotone; words vary in pitch, pacing, and emphasis. This melody carries meaning. If I say, “What a great party,” with enthusiasm or with sarcasm, the words are the same. Only the prosody differs. Prosody helps you differentiate sarcasm from enthusiasm; it also helps with the essential but less glamorous donkey work of comprehension, namely, assigning grammatical roles to words (figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2. Prosody and meaning. This grammar joke has made the rounds on Facebook. In school we learn where to place commas based on grammar, but most of us don’t use them that way when we read. Instead, the comma carries auditory significance. It signals an accent just before the comma and a pause after—hence, LET’S EAT . . . GRANDMA. In the second case we hear LET’S EAT GRANDma.

Source: © Daniel Willingham.

Even when you read silently, you add prosodic information to help you comprehend. Poet Billy Collins put it more eloquently: “I think when you’re reading in silence you actually hear the poem in your head because the skull is like a little auditorium.” If you’re reading fluently, access to individual words requires almost no attention, and that means you have more attention to devote to working out the prosody. Indeed, some research indicates that it is the development of prosody, and not the reading rate itself, that leads to the boost in reading comprehension associated with fluency (figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3. The silent reader. St. Ambrose, depicted in this statue on the Giureconsulti Palace in Milan, was a fourth-century archbishop of that city. St. Augustine famously noted that Ambrose read silently: “When he read, his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still.” Some scholars have taken this passage as evidence that people at that time typically read aloud. That hypothesis matches the fact that punctuation was then used only sporadically; vocalizing would help the reader hear the prosody.

Source: Photo by Giovanni Dall-Orto, Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Saint_Ambrose#mediaviewer/File:IMG_3106_-_Milano_-_Sant%27Ambrogio_sul_Palazzo_dei_Giureconsulti_-_Foto_di_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto_3-gen-2007.jpg

Fluency allows for better comprehension of what you read. And fluency depends on being able to read via spelling. So how do you learn to do that?

Learning to Read via Spelling

I start by clarifying what might have sounded like a contradiction. In chapter 5, I wrote, “It doesn’t work very well to teach reading by encouraging children to memorize what words look like. You have to teach the sound-translation rules.” Now I’m concluding that “reading by spelling is essential to good reading.” But these ideas don’t really contradict one another. Memorizing what words look like is impractical for learning to read, but once children know how to read, they teach themselves how to read via spelling.

Suppose I were trying to train a child to recognize words by their spellings. I might show her the word “dog” and tell her, “That word is dog.” Then I show her the word “log,” and tell her, “That word is log.” The child who can decode doesn’t need me to tell her the identity of each printed word. She tells herself. When she decodes a word using the sound mechanism, she’s identifying which word she’s seeing and she’s seeing the letter pattern at the same time. With enough repetitions, the spelling of the word and its identity come to be associated.

This is called the self-teaching hypothesis. Most kids are taught how to sound words out, but they teach themselves (without knowing they are doing so) what words look like, based on practice distributed over several years. It’s hard to give a firm estimate of exactly how long it takes to become a fluent reader. For one thing, fluency is graded. It’s not that you’re fluent or you’re not; it’s that your reading slowly becomes more and more fluent, so defining a time you’ve reached the goal is a little arbitrary. That said, the first stage of fluency is noticeable; there is some point at which a child seems to have turned a corner—she is no longer painstakingly sounding out each word but is instead reading. That might come after, say, six to nine months of decoding practice. And that’s another thing that makes it hard to come up with an estimate of when it will happen. It’s not the passage of time that’s crucial; it’s what’s happening during that time. Fluency will come faster or slower depending on how much reading the child does. The more frequently she encounters a word, the richer her knowledge of what it looks like.

What’s Happening at School

The main mechanism to develop fluency is reading. As in younger grades, reading aloud with feedback is preferable to silent reading, but that may become less practicable in many classrooms as kids get older because their reading competence diverges more. Fortunately, reading aloud is somewhat less important (compared to when students were learning to decode) because competent decoders can provide mostly accurate feedback to themselves.

It would be nice to get kids to fluency faster, especially given that national tests indicate only about half of kids have reached desired levels of fluency by fourth grade. Is there a way to hurry the process along?

Three techniques can help. First, explicit spelling instruction seems to improve fluency. Although the spelling knowledge you use to read is not identical to the knowledge you use when you’re thinking about how to spell a word, there is some overlap. So that’s a reason to include spelling instruction in schools, even though we all use word processors with spell-checkers (figure 8.4).

Figure 8.4. Spelling matters. Spelling instruction seems to promote fluency, but there are other reasons spelling is important. For example, tattoo machines don’t come with spell-check.

Source: © doris oberfrank-list—Fotolia. Modified from the image.

A second technique that can help students develop fluency is for the teacher to model reading with prosody. If reading with the right melody is the mechanism by which fluency helps comprehension, then students should know what they are aiming toward. Note too that this is still another benefit of parents’ reading aloud to their children, even as they get older. It might also help for kids to occasionally hear negative examples—the teacher reading as fast as possible, for example, or in a robotic voice.

A third technique to develop fluency is repeated reading. The child reads the same text enough times so that he can do so fluently. As when an adult models prosody, the idea is to give him a better idea of what fluent, prosodic reading sounds like, so he knows what he’s trying to do.

The research evidence for these techniques is not terribly strong, however; sometimes they seem to work, and sometimes they don’t. It may be that when the interventions were tested, they have not been of sufficient duration, or it may be that some kids had other reading issues that were preventing them from getting the full benefit of fluency. But researchers have had less success with in-school training regimens for fluency than when they’ve targeted other reading processes.

What to Do at Home

Even if the main prescription for fluency—“tons of reading”—seems obvious, how to get older kids to engage in tons of reading is not. Let’s look at what parents can do to get reluctant older kids to read.

Is There a Problem?

Before you consider your role in helping your child develop reading fluency, you need some sense of how it’s going. His school likely monitored reading closely in the early grades, but once he learned to decode fairly well, that monitoring probably tapered off. You too may have thought that the process of learning to read was pretty much done and that your child was all set. And now, when he’s older, if he seems to do his assigned reading and his teacher is satisfied, you wouldn’t have had much reason to question whether he’s a fluent reader.

You can get a sense of your child’s reading fluency by asking him to read aloud. Fluent reading will be expressive, whereas dysfluent reading will sound robotic, expressionless. The fluent reader will pause at places that sound natural, conversational. Dysfluent reading has pauses, but the reading sounds halting—you can hear that the reader is stuck on a word and is figuring it out. A fluent reader seldom loses his place while reading, and, when reading silently, he doesn’t move his mouth much. A dysfluent reader does both.

If his reading is dysfluent, that doesn’t necessarily mean he’s dyslexic. It probably means he needs more practice than other kids to develop fluency and hasn’t had it yet. And given that reading is effortful, he gets less pleasure from reading and therefore avoids it. That means practice is unlikely without a little push.

What Does a Dysfluent Reader Need?

Some parents I have known simply charged ahead and required that their child practice reading. If that’s you, the same approach I described in chapter 5 applies: brief daily sessions (five or ten minutes) with age-appropriate support and enthusiasm from you, along with a good dose of persistence to ensure that it happens. Some parents use a clever method to ensure practice; their child is allowed to watch thirty minutes of television each day but beyond that it can only be watched with the volume muted and closed captioning on.

If you take this direct route, it’s worth thinking about how you will talk to your child about the need for practice. Not many kids will respond well to a logical argument about the value of reading. Anything you might tell them, they already know. In fact, they know quite well that being a reader is associated with intelligence, and many will see their halting reading as evidence that they are just not that smart. (In fact, the opposite is probably true. Anyone who earns passing grades without being a strong reader probably has a good memory and reasons well.)

The point of reading practice is not the correction of a defect in your child. Rather, you are hoping to enrich her life. I think about reading much the way I think about food. Why don’t I let my child eat mostly mac-and-cheese and carrot sticks? Because even though she believes she’d be perfectly happy on that limited diet, I think that eating affords some of the most transcendent pleasures available. Of course, I want that for my child. In the same way, I want her to have access, through reading, to the greatest minds of history. A child who has long felt indifferent to reading won’t see it that way, but if you explain your motivation, she will at least understand that you are not criticizing her for some lack. Your goal is not for her to be a good reader; it’s that she enjoy reading.

The Indirect Route

I know some parents wouldn’t feel comfortable trying to get their teen to practice reading; how well that’s going to work obviously depends on your relationship and your history with your child. You can also try an indirect method with reading activities that demand less of her and are harder to say no to. These ideas won’t work for all families, but maybe one or two would work for yours.

You could try a family reading time once a week, in which each person reads silently together. Pitch it as a weekly time away from screens and with one another. If your child tries to show you that she doesn’t have to play along (perhaps by selecting baby books or catalogues), ignore it. She may actually be selecting books from early childhood both because she remembers them fondly and because they are easy to read. For this reason, don’t be quick to give away books your child has outgrown.

A related idea is to have the whole family listen together to an audiobook of mutual interest—and from there perhaps to one family member reading aloud to the others. Obviously the stated goal is not to practice reading. The motivation is that reading is pleasurable, spending time together as a family is pleasurable, and this is a way to do both. Time is always a problem, but even if you start with just fifteen minutes each week, that’s more than nothing, and the hope is that an interesting book will prompt some sessions to go longer. Needless to say, it’s a good idea to start with the most appealing book you can think of (figure 8.5). More on that in chapter 10.

Figure 8.5. Charles Dickens reading aloud to his daughters. If you institute family read-alouds, you might want to make things a bit less formal.

You can also begin visits to the library even if you’ve never gotten into this habit before. If your child doesn’t want to go, tell him you need to go, and say that the most convenient time for you is during a trip to take him somewhere he needs to go.

It’s true that these reading scenarios are pretty contrived. You should also be on the lookout for times that it’s logical for your child to read. If there is a younger sibling in the house, that child should be read to: the older child might take that on. (She might also read to the children of friends who visit.) Such reading is a nice chance for your child to revisit favorites from childhood and perhaps awaken memories of reading that are more pleasant than the recent ones.

I find good opportunities for my children to read when one of them wants something. When our daughter wanted an aquarium, my wife and I said, “Okay, if you’re going to take care of it, you have to learn about them.” So she got a book and read up on aquaria. The same argument can be made for nearly anything: a tree house, a green belt in karate, or a driver’s license.

A rather sneaky motivator is this implicit bargain: “if my child is reading, I will do my utmost not to interrupt him.” That sounds natural, but if the principle extends to moments where you would typically ask the child’s help around the house, then it could become a useful motivator. Of course, it is essential that you not make this bargain explicit. It will be turned down, or you will end up quibbling about what sort of reading material “counts” or whether the chores were invented so as to persuade the child to read. If you leave it unstated, it may be a while before your child puts together what’s going on, and that leaves you with much better options for how to implement it.

For some students, a forceful external motivation to improve their reading pops up unexpectedly. I once met a high schooler who was an avid baseball player. Sophomore year he made varsity but not first string, and he concluded he probably could not make a living as a player. He started to think about coaching or perhaps working in the front office of a minor league team. He did some research and learned he was much more likely to get a job with a degree in sports management. More or less overnight he became keenly interested in academic work so he could go to college. He realized that some of the struggle was getting through his textbooks, so he began to work on his reading.

Digital Difference

If your child is an uncertain reader, you might wonder whether extensive experience with digital media is somehow impoverishing her reading. There’s little indication that reading on a screen is substantially different from reading on paper.

Research does show that the way a book is put on the screen can affect comprehension, but the effects are relatively modest. For example, comprehension is better if you navigate a book by flipping virtual pages, compared to scrolling. And clickable links (hyperlinks) incur a cost to comprehension even if you don’t click them. Because you can see that they are clickable, you still need to make a decision about whether to click. That draws on your attention and so carries a cost to comprehension. But most of these effects are small, so if you’re wondering whether your child would enjoy reading more on an e-reader (or whether reading on such a device is frustrating him), I’d say “probably not.”

There is one qualification to that conclusion. If your child’s school is considering moving to electronic textbooks, be at least a little wary. Publishers are working to improve electronic textbooks, but with the current offerings, the research is pretty consistently negative. Comprehension is about the same as when reading on paper, but reading is less efficient. It takes longer to read electronic textbooks, and it feels more effortful. Quite consistently, a majority of students who have used electronic textbooks say they would rather use paper. The problem is probably not due to greater difficulty decoding an electronic book; the problem is that reading for pleasure is different from reading for school. The information is structured differently, it’s more complex, and you’re reading it to learn and remember it, not just to enjoy it.

This greater complexity and the demand that students do more with textbooks characterize the reading challenges that begin in upper elementary school. In the next chapter, we turn out attention to these complications.

Notes

“it also helps with the essential but less glamorous donkey work of comprehension”: Carlson (2009).

“‘the skull is like a little auditorium’”: Rehm (2013).

“it is the development of prosody, and not reading rate itself, that leads to the boost in reading comprehension associated with fluency”: Veenendaal, Groen, and Verhoeven (2014).

“the self-teaching hypothesis”: Share (1995).

“based on practice distributed over several years”: Grainger, Lété, Bertand, Dufau, and Ziegler (2012).

“The more frequently she encounters a word, the richer your knowledge of what it looks like.”: Arciuli and Simpson (2012); Kessler (2009).

“The main mechanism to develop fluency is reading.”: Collins and Levy (2008); Ehri (2008).

“national tests indicate only about half of kids have reached desired levels of fluency by fourth grade”: Daane, Campbell, Grigg, Goodman, and Oranje (2005).

“explicit spelling instruction seems to improve fluency”: Shanahan and Lomax (1986).

“A second technique that can help students develop fluency is for the teacher to model reading with prosody.”: See, for example, Dowhower (1989).

“A third technique to develop fluency is repeated reading.” Samuels (1979).

“The research evidence for these techniques is not terribly strong”: Breznitz and Share (1992); Fleisher, Jenkins, and Pany (1979); Tan and Nicholson (1997).

“comprehension is better if you navigate a book by flipping virtual pages, compared to scrolling”: Sanchez and Wiley (2009).

“clickable links (hyperlinks) incur a cost to comprehension”: DeStefano and LeFevre (2007).

“Comprehension is about the same as when reading on paper, but reading is less efficient.”: Connell, Bayliss, and Farmer (2012); Daniel and Woody (2013); Rockinson-Szapkiw, Courduff, Carter, and Bennett (2013); Schugar, Schugar, and Penny (2011).

“It takes longer to read electronic textbooks, and it feels more effortful.”: Ackerman and Goldsmith (2011); Ackerman and Lauterman (2012); Connell et al. (2012); Daniel and Woody (2013).

“reading for pleasure is different from reading for school”: For more on how reading for pleasure is different from reading for schools as it applies to e-textbooks, see Daniel and Willingham (2012).