Chapter 5

Learning to Decode

The period from kindergarten to second grade is an age of rapid change for your reading child. In this chapter, we look at how decoding is likely taught at your school and what you can do to support your child’s learning at home.

What’s Happening at School

You may have heard of what is referred to as the “reading wars,” a vociferous and nasty set of arguments about the best way to teach children to read. Some background on the two instructional methods that shaped the reading wars battleground will help you understand what’s happening in your child’s classroom today, and you’ll see that neither side fully prevailed in the war. Most children today are taught reading using a compromise method.

Two Traditional Methods of Teaching Reading

I’ve emphasized that the alphabet is a code that puts sounds into visual form. An essential part of reading is the process of decoding, of turning the visual forms back into sound. To understand what you read, you use the same mental machinery you draw on to comprehend spoken language; reading, in a sense, is a process of talking to oneself.

That makes it sound as though the teaching of reading ought to be uncontroversial: you teach kids the code. You plan instruction to introduce the letter-sound relationships and do so in a particular order, teaching the most common letter-sound pairs first. The umbrella term for this strategy is phonics instruction.

There are variants within this broad approach. Some people favor teaching the letter-sound pairs in isolation. Show the child the letter “o” and say, “This makes the sound AW, as in the word MOP.” An alternative is to teach letter-sound correspondences in the context of real words. Thus, instead of telling the child that the letter combination “ou” is usually said as OW, the teacher might introduce the words “cloud,” “mouse,” and “found” to help the child deduce the relationship.

The competitor idea on teaching reading holds that phonics instruction is largely unnecessary. This notion is at least two hundred years old, appearing in a French monograph from 1787, The True Way to Learning Any Language Dead or Alive by Nicolas Adam. Adam points out that when you teach a child the name of an object—a shirt, say—you don’t list the parts, telling the child, “These are the buttons, here are the cuffs,” and so on. No, you tell the child, “It’s a shirt.” Likewise, Adam says, “Hide from them all the ABCs. Entertain them with whole words which they can understand and which they will retain with far more ease and pleasure than all the printed letters.” Some fifty years later, American education pioneer Horace Mann agreed that “the advantages of teaching children by beginning with whole words are many.” He referred to isolated letters as “skeleton-shaped, bloodless, ghostly apparitions” and remarked it was little wonder children felt deathlike when confronted by them (figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. Intimidating script. Mann’s description of letters as skeleton-shaped may seem a bit over the top, but when we examine a script that is alien to us—for most English speakers, muhaqqaq, a form of calligraphic Arabic, is an example—the script looks, if not macabre, at least intimidating.

Source: Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Egyptian-_Text_Page_from_Chapter_2_-_Walters_W5614A_-_Full_Page.jpg.

Both Adam and Mann suggested that learning to read is natural. Indeed, they thought that it’s as natural as learning to speak, a suggestion still put forward today by some theorists, although they are very much in the minority. The argument suggests that what makes it unnatural and difficult is the process of drilling children in letters. Instead, we should immerse children in reading and writing tasks that are pleasurable and authentic. Give the child experience with reading that makes sense to him, that has a clear point to it, and he’ll be motivated to engage with it and will learn to read more or less effortlessly. An analogy is that children don’t need instruction to learn to speak. They are surrounded by spoken language that carries meaning and obviously has value, and so they learn to speak. In this scheme, children will learn to read from the shapes of words, not from the identity of individual letters. For that reason, it’s called whole-word reading.

But this strategy—show kids whole words—brings a substantial disadvantage. Learning to read represents a huge task to human memory because kids must remember what each word looks like, and the average high schooler knows something like fifty thousand words. A lot of those words look similar, for example, “dog” and “bog.” The phonics approach, in contrast, requires the memorization of a much, much smaller set of letter-sound pairings.

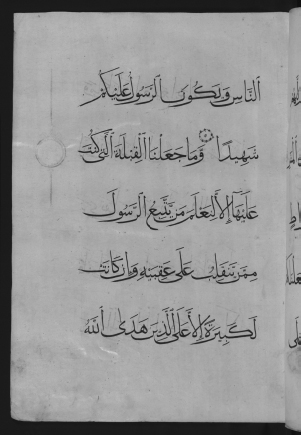

A whole-word advocate would reply that not all fifty thousand words need to be learned immediately, and we shouldn’t forget that the printed word is just one of several cues available to the reader. You can often make a good guess about the identity of a word based on the meaning of other words in the sentence. Therefore, readers should be encouraged not to rely solely on print to read. The meaning of the text is another stream of information that can help them puzzle out a word. For beginning readers, we should use reading materials that have other supports to figuring out meaning—pictures, for example, that tell the story (figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2. Meaning cues and reading. Suppose a child doesn’t recognize the word “milk.” A whole-word advocate would say that he could figure it out from the other words in the sentence and from the picture. A phonics advocate might reply that the word might just as easily be “cream.” The only way to be sure is by decoding the word.

Source: Elson Readers, Primer (Scott, Foresman, 1920).

If we do these things, say whole-word advocates—provide rich, authentic literary experiences; start with words, not letters; and teach children to use all the sources of information available—they will figure out the letter-sound correspondences as they go. Some children might need a little more support for this task, and we can provide more explicit instruction as the need arises. So whole-word advocates are not saying “no phonics whatsoever.” They are saying that the teaching of phonics shouldn’t be a driving force and focus behind the teacher’s plan of instruction.

Who’s Right?

There are a couple of ways to think about this controversy of teaching reading. The first is, “Which theory is right?” The second is, “What are the consequences of following one theory or the other?”

The Theory

The “Which theory is right?” question is easily answered. The whole-word theory makes a fundamental assumption that is almost certainly wrong.a Reading is not natural. “Natural” in this sense means that even though the task at hand is complicated, the human nervous system is in some way primed to learn the skill. It’s more or less part of your inheritance as a human being that you will learn this skill, just as a house wren effortlessly learns its song and a lion learns to stalk.

When a skill is “natural,” we expect to observe three things. First, everyone will learn the skill without great difficulty, and typically they will learn it by observation, without the need for overt instruction—after all, we’re primed to learn it. Second, given that it’s part of our inheritance as human beings, we expect that the skill can be observed in all cultures all over the world. Third, the proposal that our nervous system is primed to learn the skill implies that it will likely be evolutionarily old. It’s just not very probable that an evolutionary adaptation would have popped up in the last few thousand years.

These three features—easily learned by everyone, observed in all cultures, and evolutionarily old—are true for some human skills: walking, talking, reaching, and appreciating social interactions, for example. But none of them is true for reading. Most people don’t learn to read through observation alone, and there are peoples in the world without a written language. Finally, writing is not evolutionarily old. It’s a cultural invention that is no more than fifty-five hundred years old.

The Consequences

The second way to address the “Which is right?” question is to examine experiments that have compared how well kids learn to read when instructed using phonics or instructed when using whole-word methods. There have been a great many such experiments, going back nearly a hundred years. Whenever there is a large volume of research, there is some opportunity for picking and choosing studies that support your position, and the debates about how to summarize this research literature have been hotly contested.

The governments of three English-speaking countries (the United States, Britain, and Australia) as well as the European Union countries all came up with the same strategy to resolve the question: blue-ribbon panels of scientists were appointed to sort through the data and write a report. All four panels came to the same conclusion: it’s important to teach phonics, and to teach it in a planned, systematic way, not on an as-needed basis. Similar conclusions have been drawn by panels assembled by US scientific organizations.

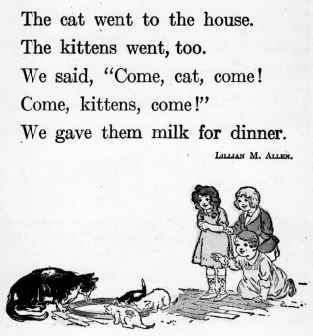

Although all these reports were in agreement that phonics instruction is important, it’s not as though kids taught using whole-word methods don’t learn to read. In fact, if you compare their reading achievement to that of kids taught using phonics, there’s a lot of overlap (figure 5.3). The advantage conferred by using phonics instead of the whole-word method is moderate, not huge.

Figure 5.3. The phonics advantage. The solid line shows a typical bell curve of student reading proficiency—a few really struggle, a few read very well, and most are in the middle. The solid line shows reading proficiency when systematic phonics instruction is not part of the reading program. The dotted line shows reading proficiency when it is. You can see that phonics instruction helps, but the curves overlap quite a bit.

Source: © Daniel Willingham.

There’s a little more to the story. The average advantage to using phonics instruction is moderate, but it’s not the case that each and every child does a little better with phonics than he or she would have done with whole-word instruction. The importance of phonics instruction varies depending on what the child knows when reading instruction begins. Phonics instruction is less important for kids who, when they start school, have good phonological awareness and understand that letters stand for sounds. They are likely to figure out the code with just a little support. But for kids who lack that knowledge, phonics instruction is likely to be very important.

Phonics instruction has come to be seen as nonnegotiable. But even if the whole-word approach to learning to decode is flawed, the emphasis on children’s literature has always seemed like a good idea to educators, and research evidence for that view accumulated through the 1980s and 1990s. It became the consensus conclusion in the late 1990s, and so was born “balanced literacy,” the type of reading instruction that your child will very likely experience.

Balanced Literacy

This position holds that phonics advocates were right: phonics instruction is essential. But whole-word advocates were right too: immersing children in authentic literacy activities is also crucial. And so balanced literacy was offered as a resolution to the conflict that had raged between the two approaches. Advocates also offered another allurement: they suggested that the balance might differ for different children. Thus, the theory seemed flexible, sensitive to variation among kids.

Balanced literacy suggests that phonics be taught, but in the context of an array of activities, especially ones that offer authentic literacy experiences (as opposed to, for example, completing a worksheet). The following list of K–2 activities comes from a handbook for teachers published by the New York City Department of Education. The full list includes ten other activities (for a total of sixteen), some of which would be familiar to you: teacher read-alouds, for example, and work on phonological awareness:

So what does the research say? Does balanced literacy work? The quick-and-dirty answer is, “It should.” We know that the pieces—phonics instruction and children’s literature—work. But giving a firmer research-based answer will have to wait, for two reasons. First, balanced literacy programs are relatively new. We know that reading success is influenced by many factors, so it’s hard to draw firm conclusions from individual experiments. Second, there is a lot of variation in what actually happens in a balanced literacy program. Programs vary, and kids’ experiences within a program vary. Indeed, a recent survey showed that American teachers largely agreed with the tenets of balanced literacy, but there was a lot of variation in what happened in their classrooms. And increasing evidence confirms what is likely your intuition: different kids learn better from different activities, depending on the strengths and interests they bring to the classroom.

Reading Classrooms Today

National studies show that most early elementary teachers are using some version of balanced literacy (few use phonics-only or whole-language only). But associated classroom activities are hard to predict, and we don’t have good research evidence bearing on which activities are best. So where does that leave us?

Classroom Activities

We are not completely in the dark as to which activities are more likely to help kids. I offer four principles from cognitive psychology that, until we have firmer research about what works, would be prudent to bear in mind as we think about classroom activities:

- Don’t forget phonics. The point of balanced literacy is “phonics plus rich literacy experiences.” If phonics instruction is one of sixteen possible activities, you do want to guard against the possibility that they are viewed as all being equally important. Some researchers have noted that planning manuals for some balanced literacy programs allot scant time to phonics instruction and don’t even list the teaching of the alphabetic principle as a goal. If the English language arts block is between 90 and 120 minutes (typical for early elementary years), I’d hope to see 20 or 25 percent devoted to phonics (i.e., twenty to thirty minutes). Naturally, this doesn’t mean that all of that time must be direct instruction or quizzing. A variety of activities could provide phonics practice. But again, when kids are practicing phonics, that practice should be focused.

- Students can focus on only one new thing at a time. Some literacy activities seem to demand that kids do two things at once. For example, when the teacher is composing text and thinking aloud as she does so, she’s both modeling the writing process and giving the students an implicit phonics lesson. But we know from other research that kids (and adults) can’t focus on two things at a time—especially two ideas that are pretty challenging. Lessons that focus on one thing at a time are more likely to be successful.

- You learn more from doing than watching. As the Bateke proverb says, “You learn how to cut down trees cutting them down.” When you’re told to watch someone, it’s easy to let your mind wander and think something else. Hence, I’m not keen on activities like shared reading, in which the students follow along while someone else reads.

- Feedback matters. Corrected errors contribute to learning. Uncorrected errors do not and may contribute to an error-laden habit. Sometimes we can catch our own mistakes, but we are less likely to do so if we are less skillful. The pro knows what she did wrong; the novice does not. Hence, when children are learning to decode, silent reading is not going to be nearly as helpful as reading aloud.

Sometimes an activity is useful for purposes other than pure literacy. A first-grade teacher told me that she used the shared writing technique for about four months with a student who simply froze when asked to write anything. She wisely saw that a bit of support from her would get him past his fear. So these techniques can be put to good use. But for the typical student learning to decode, I’d hope to see (1) learning letter-sound combinations in order of frequency, (2) memorizing a small set of very common irregular words (e.g., “the,” “and,” “when”) as sight words, (3) reading aloud, with feedback, (4) writing, and (5) lots of work with children’s literature.

Going Digital

I’ve noted that children vary in how quickly they benefit from phonics instruction and therefore will vary in how much of it they need. Thus, we’d really like the ability to fine-tune it: if a child understands quickly, you want to move him along to more interesting stuff, but if he doesn’t, he can get the instruction he needs. That sort of individualized instruction is what most teachers strive for, but it sounds hard to pull off, and it is.

Digital technologies are supposed to make this personalization possible. A computer application might titrate instruction to the child’s performance. Animation and sound could put some pizzazz into important but not intrinsically interesting material, and voice recognition technology offers the promise of evaluating student responses. You can’t do any of that with a worksheet, and a teacher can’t do it with a whole class simultaneously.

Scores of studies have examined the impact of educational technology on reading achievement, and several research reviews have pulled this work together. Researchers have concluded that technology has a modest positive effect on reading outcomes. “Modest” means technology interventions, on average, would move a student at the 50 percentile of reading up to perhaps the 55th or 65th percentile (the estimates vary).

With all the power we attribute to technology, that seems like a pretty wimpy effect. But the modest impact is actually typical for educational technology interventions, no matter what the subject: math, science, or history. More disturbing is a point made by researcher John Hattie: when you try anything new in the classroom, you see, on average, this sort of modest boost to student learning. Why? It’s not clear. (My guess is that the excitement of trying something new makes teachers enthusiastic, and that excitement rubs off on students.) The conclusion I’m emphasizing is that educational technology interventions in general (and those targeting reading in particular) have been less successful than we would have expected.

You might protest that the question, “Does technology improve reading achievement?” is a dumb one. Surely technology applications vary in quality. I think that point is exactly right. It was possible that the advantages of digital technology were so powerful that virtually any tool you developed would be pretty good. In fact, you still hear people talk this way. They point out (as I just did) that technology enables self-paced learning, that it enables the integration of other media like sound and video, that it enables individualized feedback. These advantages are displayed on the table, so to speak, and we are invited to take it as self-evident that technology will be a boon.

But of course those features must be implemented well. Embedded video may distract rather than intrigue, or the algorithm meant to adapt to a student’s reading level may be faulty. And if we’re just making a case based on what sounds plausible, we should note that teaching reading with technology also has plausible-sounding drawbacks. Technology does not capitalize on the student’s relationship with the teacher, a factor known to be important in early reading. In addition, broken or lost devices, software glitches, and compatibility problems are frequent headaches in many tech-heavy environments (figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4. A feature-rich but confusing remote. This remote has too many buttons, and they are poorly labeled.

Source: © nito fotolia.

We have learned one thing: technology alone doesn’t do much. Researchers must move on to the job of sorting out when software helps, hinders, or has no effect on reading achievement. They must also sort out the likely complex interactions among these features. That will be no small job.

The current bland conclusion is that some tech products meant to teach reading are good, some are bad, and some are in between—obvious, of course—but at least we know that we shouldn’t make a panicky decision to buy a reading program merely out of fear that we will be left behind the times. I know a decision made on that basis sounds foolish, but ask around and you’ll meet plenty of teachers who will tell you that their school or district has made technology purchasing decisions on just that basis: “We don’t want our kids to be left behind.”

What to Do at Home

Helping your child on the path to reading gets a lot more complicated once she enters kindergarten. Even if you appreciate that your child’s reading education is not wholly in the hands of the school, you still have to figure out how to coordinate what you’re doing with what’s happening in the classroom. My general take: don’t be timid about doing what you think will help your child, but be sure you communicate well with your child’s teacher. At the least, let her know what you’re doing and partner with her if at all possible.

Reading with Your Child

You have been reading to your child for years. As she starts to learn to decode, you also begin to read with her. The idea is that she reads with some support from you. The support you offer takes two forms: you remind her how to sound out words when she needs help, and you provide emotional support and enthusiasm. One-on-one practice is quite valuable at this stage of learning, but teachers have too many students to allow much of it in the classroom.

Choosing the Right Book

The right book depends on your child’s reading level, of course. Ideally, you’d like reading materials that include only letter-sound combinations he already knows. As he learns new letter-sound combinations, the books he reads include those as well. This is another reason it pays to use a phonics program that teaches letter-sound pairings in order of frequency. There are book sets (e.g., The Bob Books) that respect this order, so your child sees only words that he ought to be able to read. Your best bet is to ask your child’s teacher for recommendations because she knows how far your child has progressed.

Lots of children have a favorite book that they want to read again and again. Often it’s one they have listened to so many times that they have memorized it, and so when they “read” it to you, you can tell they are pretty much reciting. It’s not that they are dodging the harder work of decoding. Rather, they are enjoying a glimpse of what it’s like to truly read, and that’s a powerful motivator. So about half the time my youngest asked, I’d listen to her “read” Go Dog, Go (mercifully, the short version), and half the time I’d say, “Oh, I love that one too. But you read me that one yesterday. Let’s pick another book today.”

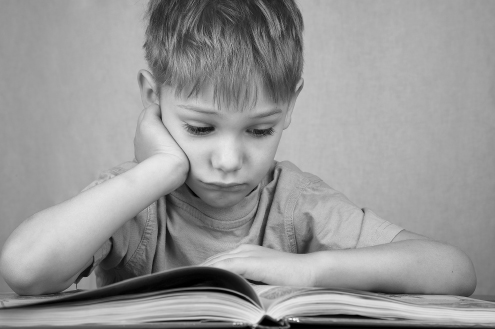

Shoot for at least one session each day, and make it brief—no more than five or ten minutes. That may not sound like much, but short bouts of practice can really pay off if they occur regularly. A little frustration during these sessions is normal, but if your child is having a bad day, just say something like, “That was great, but do you think maybe we’re done?” (figure 5.5). Don’t feel that you have to finish a book you’ve started. Of course, if he asks to keep reading, you should continue. But decoding is demanding when you are first learning, and the idea is that this process be fun. Finish the session by smiling and saying, “Thanks! I’m already looking forward to next time” or something similarly upbeat.

Figure 5.5. Reading practice is taxing. To maximize the chances that your child’s attitude stays upbeat, try to pick a time for reading practice when he’s least likely to be tired or hungry.

Source: © Ivanna Buldakova—Fotolia.com

Providing Feedback

Feedback is an important part of any learning process, and that’s what you’re there for. At the same time, feedback can be distracting. So I suggest you talk as little as possible. The child needs to hear her own voice, not yours. You want to cheer her on and acknowledge when she’s doing well—do that by smiling and nodding, not by saying, “Awesome!” or “Right!” For the same reason, don’t initiate conversations about the story. That’s just the opposite of what you do when you’re reading aloud. Learning to decode is occupying all of your child’s attention, and she can’t think about two things at once. Switching back and forth between decoding and meaning is not going to help. But of course, you should (briefly) answer questions your child asks and acknowledge comments she makes.

If your child gets stuck on a word, don’t be too quick to tell her what it is. (Likewise, when she’s writing and asks how a word is spelled, she should make her best guess before you provide support.) And don’t suggest that she guess what word makes sense. You’re practicing decoding. In fact, most kids do a lot of guessing without your suggesting it because it’s a strategy that has worked fairly well with very simple books. You’re working toward the more general skill that will carry her through the complicated stuff. So when your child guesses, just smile and say, “Sound it out,” even if she has guessed right.

Cover part of the word so all she can see is the part that’s giving her trouble. If she’s totally stumped, cover all but the initial letter (or two-letter combination, as appropriate). If she still needs help, remind her of the relevant rule: “Right. That letter usually says AW, but when there are two together, they say something else.” The same strategies apply if your child reads a word incorrectly. Don’t just blurt out a correction. Say “oops” or something else brief, and point to the missed word. See if she gets it. If not, offer support (figure 5.6).

Figure 5.6. Don’t be an auto-correct. Which way are you more likely to learn the correct spelling of “egregious”: You notice that auto-correct fixes it for you, or you’re told that the spelling is wrong and you try again to spell it correctly? When your child reads a word incorrectly, don’t just say the word: let him take another try.

Source: © Daniel Willingham.

Sometimes kids make a lot of mistakes because they try to read faster than they are really able. Other times they read excruciatingly slowly in an effort to avoid all mistakes. As in any other mental activity, speed and accuracy can be traded. There’s no reason not to encourage your child to speed up or slow down a bit. Again, this can be done mostly with gentle gesture and minimal talking.

Dealing with Frustration

You’ll note that I keep mentioning that you should smile, you should be upbeat, and so on. For me (and for many other parents I’ve spoken with), there were moments when listening to my kids read was the kind of sweet, parent-child activity I had imagined. And though I foresaw the moments that my child would be frustrated, I didn’t foresee that I would be. My child would stop to comment on complete irrelevancies. I would suggest five times that she read faster, and she would ignore me. I would remind her of the sound “ou” makes, and she would forget on the very next word. There are going to be frustrating moments, but it’s essential that you don’t show that it’s getting to you. If the interaction is negative, that emotion may rub off on reading, but even if it doesn’t, it’s going to make your child reluctant to partner with you for reading.

I can offer four suggestions if you find yourself frustrated. First, the habit of not talking much is not only good for your child (so she hears mostly her own voice, reading) but also good for maintaining your composure when you’re frustrated. Second, when you do speak, you can usually find an intonation other than frustration that carries your message in a positive way. When my youngest would look to me for help on the same word three times in sixty seconds, my inclination was to shout, “You KNOW this one.” I trained myself to say, “You know this one,” with the intonation of, “You sly dog.” I probably should have said nothing, but at least I used a positive tone. Third, remind yourself that the whole session is only five or ten minutes. Fourth, if you find that you just can’t keep it together, quit. Ask your child to read with you later. Grinding through the process gives a little practice in decoding, but it carries too high a cost in motivation.

Teaching Your Child

You may wonder whether reading with your child for one or two brief sessions each day is enough. How about honest-to-goodness instruction, not just practice?

Let’s start with the easy case. If you never thought about phonological awareness before reading this book and now realize that your six-year-old is not very good at hearing individual speech sounds, by all means, work on it. Phonological awareness exercises really are silly fun, and it’s pretty hard to do them incorrectly, so play the games described in chapter 2, as well as any others that his teacher recommends.

What about decoding? Given that I emphasized the importance of phonics instruction earlier in this chapter, you might think I’d say, “Someone has to provide systematic phonics instruction, and if the teacher doesn’t do it, you’ll have to.” But that’s not what I’m going to say.

There are very few classrooms in the United States with no phonics instruction. First, teachers know the research literature and they know that phonics instruction is important. Second, many school districts (or states) mandate that kids take tests that tap their knowledge of phonics. Third, the reason I’m so strong on phonics is not that it’s impossible to learn to read without it. It’s that systematic phonics instruction maximizes the odds that everyone in the class will learn to read. Some kids—not many, but some—really do learn with very little instruction of any sort. Others learn with relatively modest support. So sure, if you have a choice, I would urge that your child be in a classroom that teaches phonics systematically. But you may not have that choice. What if phonics instruction seems kind of light? Then what?

I encourage you to be very cautious about providing reading instruction at home. There are studies showing that such teaching can help children learn to read, but in these studies, parents are trained in specific techniques by the researchers. If you’re not trained by researchers (or your child’s teacher), you’re either going to go with your gut instincts about how to teach (which is dicey) or you’ll choose one of the many products out there for parents to work on phonics with their kids. Many of these products are not sound in how they approach reading instruction, and most are terribly boring. As one reading specialist put it to me, “Phonics worksheets, disguised as computer apps and imposed by parents on their kids, are probably the number one destroyer of reading motivation.” I see reading motivation as fragile and as difficult to bring back once it’s gone. The proper role for a parent is enthusiastic cheerleader and good model of reading, not assigner of reading chores.

That said, if your child is really having trouble learning to decode—I mean really having trouble—then I completely reverse my advice. You need to be sure that your child is getting explicit phonics instruction. That, of course, raises the question of what constitutes good progress in learning to read.

When to Be Concerned

Some typical rules of thumb for an American kindergarten might be:

But this rule of thumb really works only if it’s consistent with what’s being taught. As I was writing this chapter, I heard about a kindergarten classroom in which the teacher introduced four letters in the first nine weeks. That sounds like a pretty slow pace to me, but of course I don’t know what else the kids were doing. I’ve said before I think that many American schools spend too much time on English language arts in the early elementary grades at the expense of nearly all other subjects. So if my child were in a classroom with a slow reading pace but with terrific math, science, history, music, and art, personally, I wouldn’t complain.

•••••••••••••

As I’ve emphasized throughout this book, we need to attend to all three components of reading—decoding, comprehension, and motivation—at all ages. It’s easy to forget about comprehension as kids are learning to decode, but it’s vital that we don’t. In the next chapter, we turn our attention to the continued building of knowledge during the early elementary years.

Notes

“Hide from them all the ABCs.”: Quoted in Manguel (1996, p. 79).

“‘skeleton-shaped, bloodless, ghostly apparitions’”: Mann (1841).

“still put forward today by some theorists”: Goodman (1996).

“no more than fifty-five hundred years old”: Robinson (2007).

“blue-ribbon panels of scientists”: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (2000); Rose (2006); EU High Level Group of Experts on Literacy (2012).

“US scientific organizations”: National Research Council (1998); Rayner, Foorman, Perfetti, Pesetsky, and Seidenberg (2001).

“depending on what the child knows when reading instruction begins”: Jeynes and Littell (2000); Sonnenschein, Stapleton, and Benson (2009); Stahl and Miller (1989).

“so was born ‘balanced literacy’”: Fountas and Pinnell (1996); Pressley (2002).

“a handbook for teachers published by the New York City Department of Education”: Stabiner, Chasin, and Haver (2003).

“a lot of variation in what happened in their classrooms”: Bingham and Hall-Kenyon (2013).

“different kids learn better from different activities”: Connor, Morrison, and Katch (2004); Connor, Morrison, and Petrella (2004).

“most early elementary teachers are using some version of balanced literacy”: Xue and Meisels (2004).

“allot scant time to phonics instruction”: Rayner, Pollatsek, Ashby, and Clifton (2012).

“other research that kids (and adults) can’t focus on two things at a time”: Pashler (1999).

“technology has a modest positive effect on reading outcomes”: Cheung and Slavin (2011).

“the modest effect is actually typical for educational technology interventions”: Hattie (2009); Tamim, Bernard, Borokhovski, Abrami, and Schmid (2011).

“the student’s relationship with the teacher, a factor known to be important in early reading”: Mashburn et al. (2008).

“There are studies showing that such teaching can help children learn to read”: Senechal and Young (2008).