Chapter 4

Seeing Themselves as Readers before They Can Read

Raising a reader arguably begins and ends with motivation. If the child lacks decoding skills or the background knowledge to support comprehension, she’ll gain them through reading, and if she’s motivated, she’ll read.

In chapter 1, I noted that motivation is fueled by positive attitudes and a concept of oneself as a reader. But the catch is that your child needs to read (and to enjoy reading) to develop a positive attitude and a solid reading self-concept. In this chapter, we examine two strategies: ways you can improve reading attitudes and self-concept without your child reading and ways to get your child to choose reading as an activity.

Indirect Influences

Emotional attitudes—whether I like or hate fruitcake, for example—seem self-evidently to be a product of our experience. We taste it, we react, and there’s our attitude. Self-concept too is driven by experience. If we repeatedly choose to eat it, “proud fruitcake eater” may become part of our self-concept. Your child’s attitude toward reading and learning new things is likewise shaped by direct experience with books and learning. But attitudes and self-concept are subject to indirect influences as well.

Indirect Influences on Attitudes

Direct experiences can’t be the only source of emotional attitudes. If they were, how could you explain the attitudes of people who say they love Coke but hate Pepsi? Really, does anyone drink Coke and think yum yum, but should he drink a Pepsi by mistake think, Good God, this is vile!? (If you need proof, you’ll like a study in which experimenters put Coke in a Pepsi bottle and vice versa; it turned out that people picked their “favorite” beverage based on the bottle label, not on the content.) The emotion in these attitudes comes not from experience of the products but from emotional reactions to other objects that become associated with the product. Think about what Coke emphasizes in its advertising: that it tastes good, sure. Even more, the ads seek to create associations between Coke and things that consumers already like: young love, cute polar bears, Santa Claus, and (of course) attractive people.

When you spell out the psychological mechanism behind these ads, it sounds kind of creepy. It’s the same as the one in Pavlov’s famous experiment with the salivating dog. The dog salivates when it eats. If you ring a bell just before you feed the dog (and repeat this a few dozen times), the dog will come to salivate when it hears the bell. Advertisers are not interested in salivation but in positive emotions. A cool, funny, muscular guy in a towel prompts positive emotions in many viewers. Pair that guy with Old Spice enough times, and Old Spice becomes associated with positive emotions. It seems blatantly manipulative, and we think it wouldn’t work on us, but it does.

Reading attitudes are fostered in part by these sorts of associations. When I see a childhood favorite in a bookstore, I feel the warm glow of nostalgia. Winnie-the-Pooh or Horton Hears a Hoo makes me think of my mother reading to me at bedtime. Seeing Mrs. Piggle Wiggle or a Beverly Cleary book reminds me of the pride I felt in getting my first library card and being allowed to walk to the library on my own. That warm glow is a Pavlovian response. And indeed, research shows that positive childhood experiences with books are associated with later reading.

I’m not going to suggest you have a muscular, funny guy in a towel wander about your house, reading Homer, and muttering “fascinating . . . fascinating.” But the idea of reading being associated with warm bedtime snuggles seems practicable. So does arranging a cozy reading corner (figure 4.1). How about setting aside a time that the family reads together for fifteen minutes, each member with his or her own book? Maybe this reading time includes indulging in a special drink, which changes with the season.

Figure 4.1. Reading corners. My youngest daughter has a dormer in her room, which makes for an ideal reading spot. Her older sister lacks a dormer but makes up for it with the child-sized armchair.

Source: ©Daniel Willingham.

One of the best ways to cement this positive attitude toward reading and learning about the world is through family traditions—things that your family makes a point of doing time and time again. Family traditions reveal what you value enough to repeat, and—if done with love—build warm, happy associations. For example, my parents kept a dictionary in the kitchen and the encyclopedia a few steps away. It was a rare day that one or the other was not consulted during a kitchen table conversation. Teenaged me would sometimes roll my eyes at my nerdy parents. Doesn’t “enclose” mean the same thing as “envelop”? Who cares whether Lincoln ever served in the Senate? But I got the message: words matter, knowledge matters. And, yeah, I keep a dictionary in my kitchen now.

Here are a few other examples of family rituals:

Indirect Influences on Self-Concept

In chapter 1, I wrote that our self-concept comes from our behavior. It’s as though we watch ourselves and note how we are different from other people: Gee, I seem to read a lot, compared to most people I know. But reading a lot is not the only way to build a reading self-concept, especially when children are young. Parents communicate to children what they value as a family—what’s important in life.

I think these messages—“our family is like this”—are enormously important, and kids perceive and understand them early. Two-year-olds want to figure out how kids and adults differ. Five-year-olds perceive that families differ in their habits and practices. They discover that “finish your dinner before you get dessert” is not a rule set by adults; it’s a rule in my family, and Robert’s parents (God bless them) don’t follow that rule. Those differences prompt comparison—my house versus other houses—and so become another source of the child’s self-image.

Sometimes the message is quite direct. I remember visiting a friend’s house when I was perhaps ten and, spying a decorative dish in the living room, I pointed out to him that it was empty and that it really ought to hold candy. He thought that was an excellent idea and brought it to his mother. She said with cool derision, “We are not the type of people who put out candy in dishes.” The message clearly went far beyond candy: “This is well-bred family, and we do not engage in behaviors that might indicate otherwise.” (The missing piece for me is why a public display of candy signals the hoi polloi, but I guess a well-bred person would know not to ask such a question.)

So how can you show your child that reading and learning new things are family values? An obvious implication is that your child should see you reading. Telling your child to do something you neglect yourself won’t work (figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2. Be a model. In one of Aesop’s fables, a mother crab chides her child to walk forward instead of sideways. The child responds, “Please show me how, and I will follow.” The thought is still relevant more than twenty-five hundred years later. You can’t tell your child “go read” while you are watching television or checking Instagram.

Source: © Wenceslaus Hollar, via Wikimedia Commons.

There are other ways to signal its importance. You can display books prominently in your home. You can ensure that your child has her own bookcase and collection of books, however modest. Once your child is old enough, you can insist that books be treated as objects of respect. It might be tolerable for a doll to be tossed on the floor when a more interesting activity beckons, but books must be put away with care.

In addition to showing your child that you love to read, modeling means showing your child that you are interested in learning about the world and are always curious to learn something new. I touched on this when I pointed out that it’s not only important to answer your child’s questions thoughtfully, but also to pose your own questions to your child. And there are, of course, destinations meant to encourage curiosity—zoos, children’s museums, and the like. By all means, take advantage of them. And if you go, model curiosity by reading the information placards, not just looking at the animals or pushing the button to see the lightning bolt jump between the electrodes.

Wonderful as such excursions are, I think it’s more important to model curiosity in daily activities so as not to compartmentalize it as a special event. See a new fruit in the grocery store? Try it. Watching a ball game? Wonder aloud how often double plays happen. See an interesting bug? Snap a picture on your phone and try to identify it when you get home. Traveling somewhere for business? Find out a little about the town, even if you know you won’t have time to see the sights.

Getting Young Children to Read

We’ve explored ways to promote positive reading attitudes and positive reading self-concepts other than having the child read. The motivation for doing that is a seeming conundrum: positive attitudes and self-concepts are prompted by positive reading experiences, but why would the child read if she doesn’t already have a positive reading attitude? In this section, we consider the idea that attitudes are not the only guide for what we do and what we refrain from doing. Other factors contribute, and parents can make use of them to get kids reading.

How Do We Choose?

When we think about getting reluctant kids on board with reading, our focus is often on finding a great book. We hope the appeal of the book will overwhelm the child’s indifferent attitude, and then, once the child enjoys the book, his attitude will change for the better. But any choice, including “Should I read this book?” is influenced by multiple factors, not just the book’s appeal. To give you some sense of these factors, have a look at these questions, and answer each in your mind as you read:

When I wrote these examples, my thought was that your choice would change between the chocolate bar and lottery ticket each time I added a new element to the choice. My point was to illustrate four factors that I’ll suggest go into choices, whether it’s picking a caterer for your wedding, deciding whether to walk the dog or watch TV, or choosing whether to read a book or play a video game.

The first question—chocolate bar or $3 million—highlights the anticipated outcome. If I make this choice, what do I think I’ll get? I choose to do things that offer outcomes I like, of course, and that’s what’s on our mind when we look for books that we hope our kids will like.

But when people make choices, they don’t just think about the outcomes, because they recognize they may not actually get the outcome they anticipate. When I change the $3 million to a lottery ticket that’s potentially worth $3 million (but probably won’t win), we have an extreme example of this principle—very desirable outcome but very small odds of actually getting it—and so the modest but certain reward of the chocolate bar might hold greater appeal. Think of how a child might consider the odds when she chooses to read. Imagine an elementary school student who loved the movie Despicable Me. She’s with her father in the bookstore and he points out an early-reader novel based on the movie. She’s quite confident that this book would in principle offer a lot of pleasure. But she may doubt that she has the skills to read it. She views the book the way you view a lottery ticket.

The third question (in which I said you’d have to wait a month to get the chocolate bar) underscores still another factor that goes into choices. Sometimes an outcome looks desirable and we’re pretty sure we’ll get it, but making the associated choice incurs a cost we’re not willing to pay. I’d choose a Cadillac over my Kia, but I don’t because of the cost. One rather obvious way that readers must “pay up” is in the attention the book requires, a function of the difficulty of the text relative to the reader’s skill. We want reading material that poses a modest challenge. Another cost is the effort I must expend to get access to the book (figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3. We’re lazier than we think. You may know that manufacturers pay grocery stores to put their products on more desirable shelves, and no shelf is more desirable than the one at eye level. This is an example of accessibility affecting choice. It’s hard to believe, but simply having to move our eyes up or down constitutes a cost to finding products. To maximize the chances your child will read, you want to have books so easy to access he will almost stumble over them.

Source: © Art Allianz—Fotolia.com.

A somewhat more subtle cost is time, that is, having to wait. The value of something nice declines if we know we’ll have to wait for it. For example, if you ask me at noon whether I want dessert after supper, it’s pretty easy for me to say, “No, I’m trying to lose a few pounds.” But if you offer me cake just after we’ve finished supper, it’s much harder to say no. Cake now has more reward value than cake I’m contemplating having a few hours from now. The implication for reading is that we want ready access to books. When a child is in the mood to read, she should not have to wait even a few hours to get to the book.

The final question, in which I offered only the chocolate bar, is meant to highlight that reading is not a choice made in isolation. This offer—have it or not—seems realistic for chocolate bars, but the child does not compare reading a book to doing nothing. The child compares reading to something else he might do: read Bridge to Terabithia or, say, play the video game Portal. So it’s not enough that the child regards reading as an attractive choice. Reading must be the most attractive choice available at the moment the decision is made. This is an enormously important consideration. The average high schooler doesn’t hate reading, yet he virtually never chooses to read because there is always another activity available that is more appealing.

I’ve suggested that four factors go into whether the child will choose to read a book: (1) the pleasure she thinks the book might offer, (2) her judgment as to the likelihood that she’ll actually experience that pleasure if she tries to read it, (3) what cost she anticipates that reading the book would incur, (4) and what she might choose to do instead of read. Throughout this book, we’ll focus on ways to maximize each factor: finding books that your child is likely to enjoy, boosting your child’s reading self-confidence, and making access to books easier.

Making Reading the Most Attractive Choice

Because this chapter is about prereaders looking at picture books, some of the concerns we have with older children are not relevant. For prereaders, you don’t have to worry too much about picking just the right book or that the child frets about his reading competence. Your focus should be on making reading the most attractive choice available.

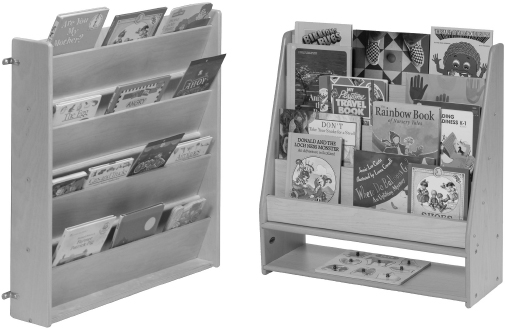

The simplest way to start is to make sure that she has access to books in places where she would otherwise be bored. Put a basket of books in the bathroom. Put another in the kitchen. Better than a basket is a bookcase that displays titles. That way your child can see what’s available, and especially at this age, book covers are more enticing than book spines (figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4. Display bookcases. These bookcases allow kids to easily see what’s available. The design on the left is wall mounted and takes up little room, so it’s a good choice for kitchens or bathrooms.

Source: © Steffy Wood Products, Inc. Used by permission.

Always have a book or two with you when you are running errands for moments when you get stuck in a line. Put a basket of books in the car, ideally in a spot your child can reach from his car seat. One destination for these errands should be the library—weekly or biweekly if you can. Regular visits allow you to fill your bookcases at no cost, and they are a great place to find a cozy corner on a cold winter’s day or to linger in cool quiet during the heat of summer. And lingering in a place with a lot of books will likely lead to reading.

Keeping Screen Time under Control

Access to books is important, but it’s not enough. Most kids will choose screens—“screens” generically referring to video content, games, or computer applications—over a book, even a readily available one. For reasons I don’t understand, moving images on a screen entrance. We stare at them as we stare at flames or ocean waves. I’ve never met a parent who said, “Yeah, he watched television a couple of times, but he really wasn’t interested.”

Very young children—those in their first two years of life—spend twice as much time watching television and videos as they do being read to (fifty-three versus twenty-three minutes per day). Slightly older children (aged five to eight years) watch more television than younger kids do (about two hours per day) although they read or are read to about the same amount of time (thirty-three minutes per day). At this age, children start to use other digital devices: 90 percent have used a computer at least once, and 22 percent use a computer daily. For console video games, the figures are only slightly lower. The use of these other devices, along with greater television viewing, means that the average five- to eight-year-old is exposed to about three hours forty-five minutes of various media each day. By the time kids are in their late teens, average media exposure approaches eleven hours per day.

My guess is that very few parents are happy that their teens spend so much time with digital devices. I’m also guessing those parents didn’t see it coming when their kids were toddlers. But as any parent knows, it’s easier to limit something at an early age than to wait until it’s a problem and then try to change course. Obviously some video content is more enriching than others—Sesame Street is not equivalent to Tom and Jerry cartoons—but if you want your child to be a reader, controlling the content of screen time probably won’t be enough. You have to control the amount.

But many parents see screens as a lifesaver when their kids are very young. Imagine the frequency of the following scenario. Mom and Dad have both worked a long day. Their four-year-old has had a long day himself. He’s hungry, frazzled, whiny. If he watches a video, he’s satisfied, and twenty minutes are now available to get some supper on the table. People often describe digital technologies as offering instant gratification for kids. They are instant gratification for parents too.

Sure, any parent feels sheepish about using the television as a babysitter, but most of us have done so. And let’s not catastrophize the situation: it’s a twenty-minute video. The concern is how parents get from there to a child consuming hours of digital content per day. You need a two-pronged strategy to keep screen time under control: setting limits and promoting independence. Here are a few ideas on setting limits on screen time:

That last idea may strike you as unrealistic. If your child drops his afternoon nap at, say, age four, will he really be able to play quietly on his own for an hour? He probably can, but he’ll need your help.

Teaching Independence

Being resourceful about entertaining oneself is a skill like any other. Children must learn it, and you can actively promote this learning. That’s the second prong in your strategy to limit screen time. Kids need to know that they can depend on themselves—not a screen, not a parent—for entertainment.

For crawlers and toddlers, make sure that the house is meticulously babyproofed so you don’t feel that you have to watch them like a hawk. Then again, do watch your child like a hawk, but do so to learn what interests him. If you’re trying to build independence, you need to know what he finds absorbing. I once saw a mom encouraging her twelve-month-old to play with Play-Doh, but he was having none of it. He kept fooling with the Play-Doh canisters. She finally realized that he was intrigued by how the top fit. She ditched the Play-Doh, got out half a dozen Tupperware containers, and he was happy for about thirty minutes as he removed and replaced the tops.

When setting your child up for independent play, focus on one activity at a time. If she’s got an idea of what she wants to do, great. If not, try to involve her in what you’re doing. A toddler can hold a dustpan while you sweep, or a bowl while you mix, and it takes no more than this sort of job for her to feel she’s helping. A three-year-old can tear lettuce for a salad or stack books on a shelf. A four-year-old can set a table or water houseplants. It won’t be long before your child doesn’t want to help around the house, but at this age, kids are eager to do so. Of course it’s faster and easier to do it yourself (and you won’t make a mess), but it’s worth putting in the effort to teach them (figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5. Independence. Sometimes it’s impossible for your child to help you in what you’re doing, for example, when you’re writing or using a mattock in your garden. In that case, suggest that he do something similar. If you’re writing, he’s coloring. If you’re gardening, he’s watering plants.

Source: © Chris Parfitt via Flickr.

Not only will it take effort, it will take time. Think of building your child’s independence in stages. Initially expect that you’ll be sitting nearby engaged in your own activity and your child will frequently check in with you. She’ll ask a question or request help. My basic strategy is to respond as briefly as possible. If she wants me to engage in the task with her, I say, “I’m doing this now. And you know what? It looks like you’re doing great with that. How about you continue, and we’ll check in with each other in a few minutes?” (To be clear, I’m not saying I never interact with my kids. I’m talking about times when I’m self-consciously trying to build independence.)

Because building independence is a process, you should have higher expectations for your child’s resourcefulness as she gets older. When my six-year-old says, “I’m bored,” I’ll suggest four or five things she might do. If she doesn’t bite, I say, “Well, that’s what I’ve got for you.” Usually she finds something to occupy herself. If she drapes herself across the sofa and moans, “There’s nothing to doooooooo,” I tell her that she’s free to moan in her room but not near me.

One final thought on goals. Other parents have usually reacted to the screen restrictions in my home with a shrug, but I occasionally hear a slightly sharp edge in a friend’s voice as he says something like, “You can’t protect them forever,” or “They’ll see it at other kids’ houses, you know.” My goal is not that my child never sees a screen. My goal is to make space for reading, so that by the time she’s ten, reading is so firmly socketed in her life that it cannot be threatened by an obsession with gossip websites, the latest video game, or anything else.

•••••••••••••

In most schools, kindergarten marks the beginning of earnest reading instruction. In the next chapter, we begin our discussion of this age.

Notes

“based on the bottle label, not on the content”: Woolfolk, Castellan, and Brooks (1983).

“Old Spice becomes associated with positive emotions”: Stuart, Shimp, and Engle (1984).

“positive childhood experiences with books are associated with later reading”: Baker, Scher, and Mackler (1997); Rowe (1991); Walberg and Tsai (1985).

“and so become another source of the child’s self-image”: DeBaryshe (1995); Evans, Shaw, and Bell (2000).

“they recognize they may not actually get the outcome they anticipate”: In the research literature, these are called expectancy value theories (e.g., Wigfield & Eccles, 2000).

“average media exposure approaches eleven hours per day”: Rideout, Foehr, and Roberts (2010).