chapter THREE

Level II: Domains of Communication

Affect, Power, and Meaning

In Chapter Two, you began to learn how to read the room at Level I, the action stances (move, follow, oppose, bystand); Level I is the first component of the behavioral profile that will become useful when complete. This chapter explores Level II, communication domains: affect, power, and meaning.

We never just make a move, a follow, an oppose, or a bystand. We make it in the domain or language of affect, power, or meaning. Figure 1.1 located these domains in the context of our broader model of structural dynamics. I call this level “domains” to call attention to how the three terms describe both the territory where actions originate and their aim or purpose. One might also think of each domain as an orientation or “world” that preoccupies people as they communicate: some focus heavily on their and others’ feelings (affect), others on getting things done (power), and others on what it all means (meaning).

The key to understanding what you hear lies in recognizing speech in each domain and combining that insight with your awareness of the speaker’s action stance. Suppose you tell a friend that you are reading this book by Kantor. “It’s about leadership,” you say (thereby making a move). Your friend asks, “Why a book on leadership?” (inviting you to clarify your move). Three answers could follow:

| Speech Act | Stance and Domain |

| I’m reading it because I care about the people around me, and I want to do my best to maximize the quality and depth of those interactions. | A move in the affect domain (intimacy, nurturance, relationships, social connection) |

| I’m reading it because I believe that these skills will help me get what I want [for example, promotion, resolution of an existing group conflict, success]. | A move in the power domain (what we want and how to achieve it) |

| I am reading it because I want to increase my knowledge; I want to expand my understanding of this model that I have heard so much about. | A move in the meaning domain (search for ideas, meaning, truth, correct understanding) |

You can tell what domain speakers are occupying (coming from and pointing toward) by their use of specific words and phrases that typify the three areas, such as the ones I italicized in the left column of the table here. Notice also that the communication domains add not only linguistic tone and context but purpose to the four action stances. I like to speak of them as language domains, to indicate that they are languages through which each domain’s purposes are realized.

The space in which we each focus our language is connected to a deep inner sense of what matters. Each of us has preferences about operating in one domain or another, despite the fact that each domain is indispensable to successful verbal interaction. From what you know already of COO Ian and HR director Martha, you can safely assume that they and other members of the ClearFacts team will differ not only in the stances they prefer but in which domains matter most to each—affect, power, or meaning. Ralph’s challenge as CEO will be to combine his recognition of stances with a sense of domains. Only by being aware of conflicts at this level will he be able to effectively manage the speech of the group. Before we examine each domain more closely, let’s get a sense of how they display themselves at ClearFacts.

THE LATEST CLEARFACTS WEEKLY MEETING

With Art’s permission, Ralph opened the meeting by telling the group that he’d arranged a session between coach Duncan and Art, who’d exploded the previous week, and that Art wanted to “put the episode behind us and move on.” Ralph endorsed that request, especially in light of today’s big agenda.

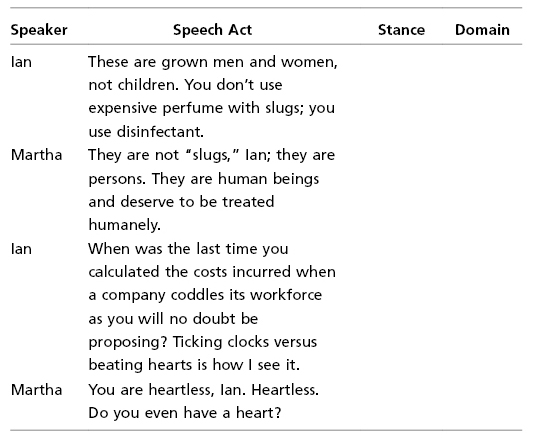

Ralph proceeded by telling the team that ClearFacts was on target with its acquisitions and green energy investments, positioning itself well for the future. However, they needed to discuss how to handle excessive headcount totals since ClearFacts had acquired a start-up in Florida. The team noted that throughout ClearFacts, because times had been good, managers had been keeping poor performers on the payroll. Now the purchase of the start-up would flood the ClearFacts ranks to overflow in key departments. Pink slips were inevitable, the team agreed, but should they sweep the house quickly? Or should they try to preserve morale by holding costly meetings to explain their decision? At that point, the following exchange took place between Ian (COO) and Martha (VP of HR). Take a moment to fill in the action stance you see behind each of the statements. Leave the Domain column empty for now.

In a post-meeting analysis, Ralph told Duncan about the sequence he’d noted in these remarks: that Ian would oppose and Martha would move and oppose him, at which point Ian would oppose her and make a move of his own. Back and forth. Ralph was intrigued.

RALPH: I’ve never been able to figure out what is going on with them. They’re running the Leadership Development Center together, training “high-potentials,” yet they often quarrel like a couple divorcing in front of Judge Judy. They drive each other crazy—both of them stuck. It’s like whenever things heat up, they seem to pass each other by. As if each is talking to someone else.

DUNCAN: Indeed. In fact, Ian and Martha speak different languages—Ian the language of power, Martha the language of affect. When they’re running trainings together, they manage to keep their differences under wraps, though occasionally their very different answers to a trainee’s question get confusing. Then, I’ve seen, Martha resentfully defers to Ian. In your weekly team meetings, when, as you say, “things heat up,” her unhappiness erupts.

With that, Duncan explained the three domains of affect, power, and meaning.

THE DOMAIN OF AFFECT

Figure 3.1 briefly summarizes the affect domain in terms of its general orientation, the territory it covers, its broad goals, and what it amounts to at its best and worst.

Figure 3.1 Affect Communication Domain

The language of affect is the language of intimacy and nurturance, of being connected with others in the world. When we speak the language of affect, we are attending to the relationships between individuals and to each individual’s sense of well-being. Affect is also the language of emotion, caring, and connection. Following are some statements in the affect domain. (Note that the interpretation of stance might differ depending on the sequence of speech acts in which each statement took place.)

| Speech Act | Stance in Domain |

| Any time you feel sad or frightened, you can ask me to hold you. | Move in affect |

| I’m convinced that raising that issue will open an emotional can of worms that will license the ranks to act like children. | Oppose in affect |

| I’ll do as you’ve asked. Since they both trust me, I’ll try to get them to embrace and make up. | Follow in affect |

| It seems that whenever you two get too close, you have a fight that puts you at a “safer” emotional distance. | Bystand in affect |

Metaphorically, to speak in affect is to speak from the heart. Individuals who are strong in the affect domain often value their relationships with others as much as or more than they value the tasks or outcomes at hand. In a conversation in the affect domain, you will hear them use such words as empathize, sensitive, well-being, feel, care, love, and hate.

Individuals who are tightly locked into one of the other two language domains and who are also intolerant of the language of affect may respond dismissively to these vocabularies openly or privately. “Insubstantial” or “irrelevant,” a meaning advocate may think. A strict power advocate may think “shallow,” “mediocre,” or “expendable.” They reflect the reality that the affect domain was formerly relegated primarily to the family arena. By the same token, strict advocates of affect may pejoratively judge those committed to the other domains: “detached” or “obtuse,” they may say and think of fierce meaning advocates; they may consider strict power advocates “driven” or “heartless.”

In corporations, affect is still the least commonly heard of the three language domains, although an affect revolution has been accelerating in business over the last thirty years. Because it is not the typical linguistic means for reaching the goals of a business organization, affect is often ascribed to “touchy-feely” types. In some highly competitive organizations, when the language of affect is used, it is often confined to pre- and post-meeting activity and to restaurants and bars where individuals are tacitly allowed to connect with one another on a more informal basis.

But evidence abounds that corporate groups now recognize the importance of affect. In large part due to Goleman’s theory of emotional intelligence, leaders are now commonly evaluated on “how effectively [they] perceive and understand their own emotions and the emotions of others and how well they can manage their emotional behavior.”1 Developments in neuroscience validate a frequently held, but unsubstantiated, view that “we are wired to connect.”2

Families do not always stress affect. Family systems deficient in affect and work systems abounding with affect are both more common than one might think.

THE DOMAIN OF POWER

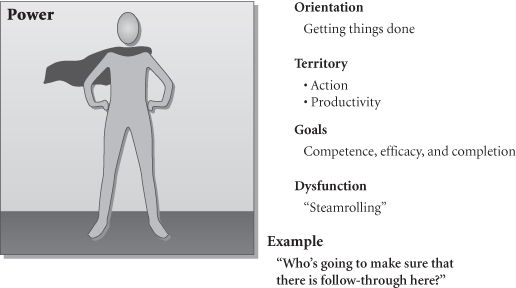

Figure 3.2 briefly summarizes the power domain in several respects.

Figure 3.2 Power Communication Domain

The domain of power involves the freedom to decide what we as individuals or organizations want and the ability to achieve it. However, people do associate the word “power” with force and with images of constraint, control, coercion, absolute authority, and tyranny; and there is also a place for these dark sides of power in our theory. Nowhere else than in the power domain is it more important to keep in mind the light and dark sides of our speech and other behavior. In this chapter, however, we will emphasize the light or positive face of power. Think of effectiveness, efficacy, competence, potency, skill, and productivity. These we distill down to efficacy and a sense of competency when identifying the basic goals and purposes of communication in the power domain.

Metaphorically, the power domain represents the muscle and sinew of an organization: few conditions are more pathetic than an awareness of what is wanted or needed combined with the lack of ability, freedom, or confidence to attain it.3 Because of its focus on the completion of tasks to achieve objectives, power tends to be the dominant language in corporate life. In power we translate the ideas and theories of the meaning domain into real action in the world. One might say that in the corporate world, power language often reigns supreme, with meaning in a distant second place, and affect another twelve lengths back.

In manifestly intimate systems such as families, marriages, and other love-based partnerships, affect might appear to have no significant rival, but power and meaning also have major roles to play. The following are examples of statements in the power domain.

| Speech Act | Stance in Domain |

| Folks, it’s time to put all talk on the shelf and focus on action. | Move in power |

| Unless you add “putting the right people in place,” my concerns about competitors catching up will continue to intensify. | Oppose in power |

| Your idea of investing heavily in training and skill building is spot-on. It serves both our short-term competitive concerns and our long-term growth goals. | Follow and then move in power |

| What you all seem to be saying is that our on-the-ground tactics are perfectly in sync with our best-case growth trajectory. | Bystand in power |

At work, such words as action, achieve, move forward, accountable, outcomes, and performance signal the power domain.

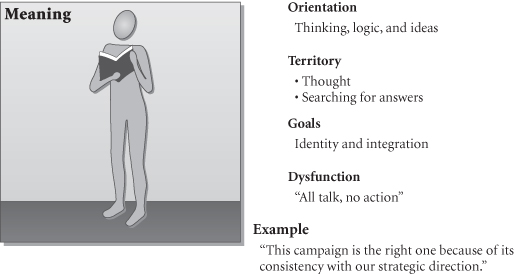

THE DOMAIN OF MEANING

Figure 3.3 briefly summarizes the meaning domain, the space in which we seek understanding of the most difficult questions posed by the key worlds in which we live. It is the territory of ideas, purpose, high value, and an unfiltered access to information—all toward the coherent integration of thought. When we speak in the meaning domain, it is to test and cement our understanding of our identities, try out new theories, gather more information, and learn from those around us. Ultimately, the language of meaning is a search for truth in either of two veins, analytic and philosophical. The following table lists examples of statements in the meaning domain.

Figure 3.3 Meaning Communication Domain

| Speech Act | Stance in Domain |

| I’m concerned we’re losing sight of our collective purpose. | Move in meaning |

| I find this department’s dogmatic commitment to pluralism no different from so-called narrow fundamentalism. | Oppose in meaning |

| I support the idea of making sure we triple-check all the facts before including them in our report. | Follow in meaning |

| The ongoing discussions between philosophy and the social sciences could conceivably result in an entirely new field of knowledge. | Bystand in meaning |

Metaphorically, to speak in meaning is to speak from the mind. In meaning, we seek to develop a shared community of thought with others in conversation. In this domain you will hear such words as ideas, purpose, integration, logic, understanding, theory, values, and patterns.

Of the three domains, meaning is the most linked to context. Different kinds of organizations define their meaning differently. In the business world, conversations about vision, strategy, and purpose lie squarely in the domain of meaning. Many conversations in engineering, health care, R&D, and information systems departments also evolve in the meaning domain as individuals try to solve technical problems or seek out the appropriate information for decision making. In the family context, meaning conversations are those that deal with what we stand for and believe in as a family. In the church, meaning conversations attend to the highest theological levels.

Individuals who are most comfortable in the meaning domain often enjoy research and data gathering, and discussion of philosophy and theories. The pursuit of knowledge and information is a prime motivator.

For exercise, look back at the dialogues in this and the previous chapter. Try to ascribe one of the three domains to each speech act. (Be easy on yourself: some speech act wordings are difficult to interpret neatly when the context is unclear or mixed, or when a speaker changes the context.)

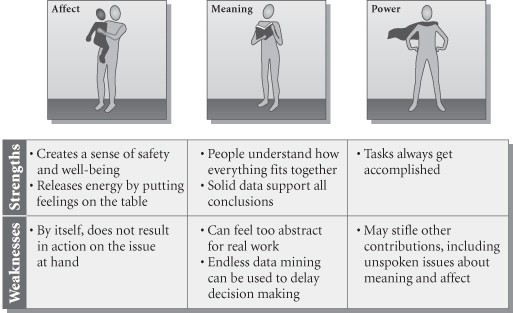

THE VALUE OF ALL THREE DOMAINS

As I said briefly earlier, structural dynamics asserts that a balance of all three domains is necessary over time for the effective functioning of any organizational system and for the highest functioning of good leaders, good parents, and thoughtful lovers. In some measure, the presence of all three domains is important because when one is overly dominant, it can have as much detrimental impact as when entirely absent.

Each domain has strengths and weaknesses, as Figure 3.4 suggests. For example, the affect domain creates a sense of safety and well-being and helps establish strong bonds between individuals. (“How are we all feeling about this? Honestly all on board?”) These bonds can prove invaluable in organizational crisis. If a team can function only in affect, however, it is unlikely to perform up to organizational expectations. Meaning provides alignment between individuals through a shared sense of purpose and an understanding of the “why” behind actions. (“Does this plan serve your department’s needs?”) Overused, it can serve as a hiding place for those uncomfortable with taking action or with expressing concern about relationships or about speaking the language of love directly. The domain of power is critical to moving forward and making things happen. (“Okay, what’s step one?”) Focused on exclusively, it stifles other contributions and can turn thoughtful momentum into tyranny and reckless acts. And, of course, it too can cast a shadow of neglect on relationships at work and in love. (“Let’s just vote and move on!”)

Figure 3.4 Each Domain’s Strengths and Weaknesses

STANCES AND DOMAINS ACROSS THE CLEARFACTS TEAM

Earlier in this chapter, I provided some dialogue between Martha (whose domain preference is affect) and Ian (whose is power) that showed how the clash sometimes gets them stuck. Try noting the stances and preferences also in this additional bit of dialogue from the meeting described in Chapter Two, in which Howard was criticizing Art’s ads:

| Speaker | Speech Act | Stance and Domain |

| Howard | What’s the central theme in this TV ad? I don’t get it. | |

| Arthur | Well, the first few seconds are metaphoric, not how things actually are. | |

| Howard | But the rest doesn’t fit at all with the first part. | |

| Arthur | That’s the point; the effect it means to convey is captured in comparison. Its message is intentionally nuanced. | |

| Howard | When I convey a message to big customers, I avoid nuance; the suckers don’t get “nuance.” They want profit, and ads that help them make it. |

As coach Duncan helped CEO Ralph learn to listen for the patterns of stances and domains among the members of the team (including Ralph himself), they had the following exchange.

DUNCAN: More than 50 percent of Ian’s contributions challenge someone else’s contributions. That’s his opposer stance propensity. And when he opposes he is usually focusing on expediting solutions to make things happen. That’s his propensity toward the power domain. On the other hand, more than 50 percent of Martha’s contributions are moves laced in affect.

RALPH: Okay, but those two are so obviously different. How about Art and Martha?

DUNCAN: Art and Martha sound alike when discussing people issues, or any subject for that matter. But whereas she relies heavily on feelings and the language of affect, he balances his own propensity toward affect with the language of meaning.

RALPH: So those two could also generate storms?

DUNCAN: Yes, and if in general it can be said that storms develop from miscommunications, you, my dear friend Ralph, are making some worse.

RALPH: I think I’ve got you here, Dunc. I don’t remember my being part of any storm. We’ve talked about the storms on my team … But I have consciously held myself back from stepping into the fray.

DUNCAN: (After a dramatically enigmatic expression that tends to irritate Ralph) I’m guessing you’re annoyed. Even with me. Right now. When you are looking for explanations and they are withheld, you tend to react. Understanding things is important to you. In fact, when anybody’s freedom to expound ideas is dismissed or systematically undermined or ruled out, you are capable of exploding. When you think you are consciously keeping a lid on your potentially stormy behavior, veins show up in your forehead and neck. Remember recently when Ian rather ruthlessly dismissed one of Art’s poetic expostulations? Those veins in your neck and head seemed ready to burst.

RALPH: (Feels his body tensing up; tries in vain to shut down memory of a violent confrontation with his father) (Muttering) Son of a bitch. (Aloud) I know the moment well.

DUNCAN: (Softly, muted) Ralph, we both know that there is a story here. But we’ll get to that later. For now, let this suffice: nothing is more important to you than meaning—your need to understand, your constant search for truth in all the worlds around you. When power is used to assault meaning, when the pursuit of understanding is shut down, you don’t like it.

RALPH: Meaning? I’m hung up on meaning?

DUNCAN: When you are unobstructed, you gravitate to the land of meaning. But you can get stuck there. Oh, you are pretty trilingual, but you tend to drift into meaning.

Duncan takes note that Ralph’s voice is softer than usual, Ralph’s mind roaming, his energy subdued. Ralph doesn’t say so, but now he’s thinking of something he heard recently from Sonia, his wife. As I noted earlier, to Ralph, the quality of his marital sex life is his main measure of the ongoing quality of his marriage, and, as he’d been telling Sonia, that quality now is high—“as good as it gets.” She wasn’t disagreeing, but she did say to him, “Let’s face it: it is a bit hard to get you out of your head and into your body.”

Hmm, thinks Ralph. From meaning to affect?

PROPENSITIES TOWARD DIFFERENT DOMAINS

Most individuals choose one communication domain over the others, though many comfortably “speak” all three, assigning different weights to each while reserving their dominant choice for contexts that call forth their most representative self. Asked about this choice once they learn the concepts, they will say, “I haven’t thought about it in these terms until now, but yes, you could say I have a preference for one language over the others.”

When people come away from an important event—a heated conversation, let’s say (in which, not incidentally, they are likely to have been overplaying their language of choice)—with different interpretations of what happened, their communication propensities may be implicated. Our dominant communication propensity makes us more likely to see, hear, attend to, and explain only portions of what those around us are saying. Think of it as a lens with two functions: a sensor that attunes us to hearing certain kinds of information, and a filter that screens out other kinds of information. If your language of choice is meaning, for example, you will notice and cull out issues in that domain, using the language of meaning to describe them. You will be less attuned to issues of power and affect.

COMMUNICATION AT THE INTERFACE

The general structural perspective works from the notion that much of the most vital action in any system takes place at the interface between two entities. When we talk about healthy organizations, we see that effective conversation is taking place more or less consistently at the interface of the organization’s key subsystems—marketing and sales, for example, or R&D and finance. Similarly, individuals like Ian, Martha, Art, and Howard are also subsystems themselves, and their communication occurs at the interface as well: a common space created where they can listen and hear each other. In diagnosing failed communications between individuals and between groups, an understanding of the three communication domain preferences and their interfaces is key to establishing a place where meaningful communication can occur.

Communication Interface Between Two Individuals

Let’s take a look at the interface between two individuals by eavesdropping on a typical exchange from a leadership training session co-led by Ian and Martha.

TRAINEE: (To Ian) Sir, I understand the logic of your explanation of what it takes to be a leader, but I have no appetite for your “warrior” metaphors. Does that mean I should give up trying?

IAN: You’re damn right (carefully timing an ironic pause) … soldier.

MARTHA: (Hurrying to catch up with Ian’s barb) Not in the least, if …

Ian and Martha stumble on to the end of the session doing their best to cover over the stark difference in their training models, which they had agreed not to make public. In their post-session debrief:

MARTHA: What you said to that—and, I might remind you, universally liked and respected—young manager was unnecessarily harsh, cruel, and simply wrong.

IAN: Catch your breath, Martha. I was simply using irony to test his mettle. I was saying that the life of a leader is, like Hobbes’s view of the life of man, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” You are no leader if you can’t handle unnecessarily harsh and often cruel realities.

MARTHA: Let me breathe as I will, Ian. You’ve read his assessments. His staff loves him, they follow him, they produce for him.

An interface between any two components is where their outer boundaries touch. You are already familiar with our practice of spatializing system concepts. In Chapter Two I said that thinking spatially can shed light on and help unravel the complexities of relationships in human systems. Let’s take this latter claim a step further.

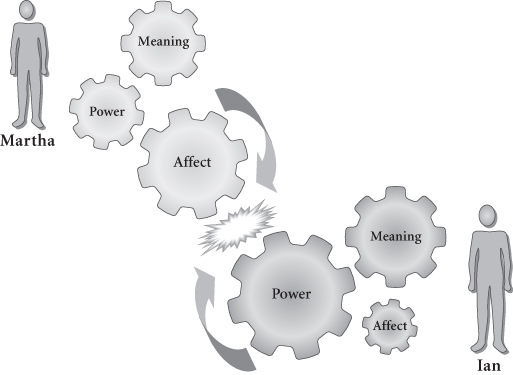

Figure 3.5 illustrates Martha, who has a very strong propensity for affect and has preferences for meaning and power as well, and Ian, who has a very strong propensity for power, some for meaning, and no observable propensity for affect.

Figure 3.5 Communication Problems: Martha and Ian

The figure represents Ian’s and Martha’s very different communicational realities. In fact, their primary preferences are so dominant that they have difficulty finding a communication domain where they can “truly talk” together. They are capable of meaningful conversation in meaning or power, but over time another obstacle has impeded their ability to get along. As people encounter repeated conflict, they build protective walls designed to reduce penetration and other forms of damage. Ian dreads any undermining of his commitment to efficiently getting things done. Martha dreads any undermining of her commitment to taking care of the people she’s responsible for. Although she is by nature a strong mover, with Ian she is triggered to become a stuck opposer.

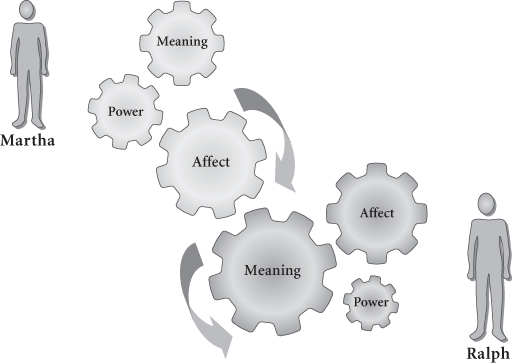

Let us look at an example of a more productive communication interface, that between Martha and Ralph, her boss (shown both in the following dialogue and in Figure 3.6):

Figure 3.6 Clear Communication: Martha and Ralph

| Speaker | Speech Act | Domain |

| Martha | I am so emotionally drained from battling with Ian constantly—I don’t know what to do with this relationship. | Clearly affect. |

| Ralph | I hear you. You are like a mother hen: fierce in protecting her brood. | Comfortable with the language, Ralph joins her in affect. |

| Martha | (Laughs) Thanks, but don’t make me blush. | Still in affect. |

| Ralph | Let’s get Ian in here and talk through your differences; if we lay the different viewpoints on the table, we should be able to reach some agreements. That done, let’s all talk about what we can do to ensure that your shared goals are met on time. | Ralph first shifts to meaning, then to the power domain. |

Martha is also able to move into the meaning and power domains, and is more open to doing so when others demonstrate that they are capable of valuing and acknowledging her communicative intents in the affect domain.

Trilingual Leaders

In structural dynamics terms, being trilingual means that you can hear and speak in all three communication domains, even if you prefer one domain. This capacity is essential for leaders who want to capture the full value of the differences among domains within their organizations. Being able to speak effectively across the communication domains allows leaders to be heard by their full constituency and to make people feel listened to and understood.

Leaders who do not understand the communication domains may unknowingly shut down the domains that differ either from their own propensities or from the organization’s dominant domain. In their organizational systems, leaders occupy a special and extremely central position. When they repeatedly communicate their own ideas using one communication domain to the exclusion of the others, when they “hear” what others say primarily through the lens of that domain, they are sending a signal to the system about how to speak and how to be heard. Over time, those messages will silence the voices of the other domains.

Becoming Trilingual

A very few individuals speak all three languages with equal facility. For most leaders, the first insight is the realization that being able to expand their repertoire is a worthy and attainable desired state. Typically, they reach this conclusion by discovering that they are deficient in at least one domain, thus limiting their ability to successfully interact with key others in that language. The next step is recognizing the validity and value of the other language, even when they can’t yet speak in it. The final stage of trilingual competency can take two distinct forms: when the leader is able to speak in all three communication domains at will; or when, as team leaders, individuals learn to call on others at the strategically optimal moment to execute language skills that they themselves lack.

As individuals develop their trilingual capacities, they should assume responsibility for

- Knowing when they are speaking in a language (that is, a communication domain) that is different from what is appropriate for the subject and the audience

- Recognizing the validity of another’s preferred language system

- Learning to value the strengths and tolerate the limits of each team member’s repertoire

AN INSIGHT INTO IAN’S CHOICE OF DOMAINS

Like choices of action stances, choices of domain, too, are influenced by Level IV of structural dynamics, the level of deep personal history and enduring identity stories, which I’ll describe in Chapter Six. The following will show how this applies to Ian, who maintains his own personal stories and is clearly a mover in the domain of power, almost aversive to emotional expression.

Since youth, Ian has struggled between domains as a result of his parents’ competition for most dominating influence. When Ian was born, his father, George Maxwell, was a recent West Point graduate from a Midwestern town. Two years before, George had married Ian’s mother, Margaret Wells, a schoolteacher from the same town. Nineteen years later, the marriage ended badly after a sustained struggle over Ian.

The couple’s war took place in two arenas: one was their bedroom, from which sounds of frightening anger and puzzling cries of pain led their son to close his ears in muted memory; the other was all the shared spaces where Ian was raised amid dual and dueling orders that forced him to choose sides.

“Strong boys never cry.” When Ian was not yet five, his father declared him ready to ride his first two-wheeler solo—a ride to the corner, turn, and ride back, all on the sidewalk. Turning on a dime is too advanced for most kids, but George insisted he do it. “You are no ordinary kid. Do it. Just remember, control is in the back pedal.” Too scared to disappoint, Ian set off, not taking a single breath until he managed shakily to navigate the turn. On the easy ride back to his father’s arms, arms prematurely raised in triumph, a squirrel darted across the path. Instinctively Ian jerked the bike and tumbled hard, scraping wrist, knees, and forehead on the pavement.

His father, quickly at the scene, retrieved and inspected the bike, leaving the brokenhearted son to pick himself up. “Good,” said the father, as if to the bike, “no damage. Not a scrape.” He never glanced at Ian’s wounds. Instead, he zeroed in on the tears in Ian’s eyes. Even the four-year-old Ian knew that asking for solace in this way was a humiliation for him and a disappointment for his father. What he didn’t expect and never forgot was what followed—no violent shaking this time, but the violence in his father’s voice, through all but frothing teeth: “Don’t ever let me see you cry about anything again. Hear me? Never again.” Ian heard.

By age seven, Ian knew who was in charge: Colonel George Maxwell. By that time, the only option—if there was one—was to please his father. When the father was away on military duty, Ian’s mother cautiously tried to fill the parental vacuum in maneuvers designed to counter her husband’s militant control. Ordinary comforting (“pampering,” George called it) was out. Reading was not. It was her secret weapon, an attempt to guide his mind when cultivating his heart was out of line. No longer a schoolteacher, she now had Ian as her private student—their only connection. But she and her son soon learned that when his father returned home on leave, he would deliberately erase any mark of weakness “she’d” left on “my boy.” Like an invocation to a god, the phrase “He is strong and she is weak” was drummed into Ian’s psyche.

By age thirteen, George Maxwell had seeded in his receptive son a dream that boy would follow man by going to West Point. There, the son would also learn “character” (meaning honor, duty, and integrity), “discipline” (never cracking under pressure), and “strength” (the will to endure pain). In the father’s view, these “virtues” were the precursors of leadership that would be instilled in Ian when—not if—he “ rightly” chose the academy. Of the three virtues, strength was “most visible and susceptible to proper influence.”

When Ian was fifteen, George—not one to leave things to chance—concocted a game (“our own Test of Strength”) he insisted Ian not reveal to the mother, though she soon found out. In the game’s first round, Ian was to tighten his stomach muscles to receive a fist-clenched blow, a full-strength punch from his six-foot, 180-pound father. Ian would be “fit” when he could “stomach” (a crude joke only the elder seemed to enjoy) ten such blows without flinching or giving ground. Stumbling on father and son conspiring at this ordeal and sensing her husband’s insidious intentions, Margaret secretly vowed to steer her son out of the dangerous warrior path and onto a path of scholarship for her straight-A son, so uncommonly gifted in language, literature, and science.

Within six months, Ian could proudly stand ground through two punches, crying “uncle” only after the third. At age sixteen, a fat-free, steel-framed football star, he held out through seven and emphatically announced, “I will be fit in three months.” And he launched a grueling, physically punishing bodybuilding regimen that included gradually increasing the weights he held at the back of his neck as he did more and more sit-ups.

On schedule, Ian took ten punches without a wince, and Colonel Maxwell, bursting with pride, declared Ian fit to be his son. Ian’s “victory over pain” showed him to be someone who does what he sets out to do, “a reliable ‘doer’ ” and a “future leader of men.”

When Ian ultimately chose West Point over Princeton, Cornell, and MIT, Margaret covertly retreated into a mental courtroom she’d been devising in which she’d put her marriage on trial. Silently preparing enough beef stew to last for days, she disappeared into her locked room and came out changed. She embraced her son, congratulated him in morbid monotone, flashed a glance of disgust at her triumphant husband, and silently vowed to divorce him “at the right time.” She never did, but she never entered the same bed with him again. “It was worse than divorce,” Ian would later confess to coach Duncan. “The home to which I briefly returned after the Point was like a funeral parlor.”

These and similar stories from Ian’s childhood provide a context for the behavioral propensities he evidences in his relationships at ClearFacts, particularly with Martha and Ralph. His clashes with Martha mirror his parents’ struggles of power versus affect. His relationship with Ralph, as you will see in Chapter Four, has shades of his relationship with his father.

SURPRISE AT THE MEETING’S END

The weekly meeting with which I opened this chapter went well through its business agenda, and the team felt good about its work. But at the close of it, Ralph said, “One last thing. I want to share with you a note from one of our employees that concerns me. This came through the mail from an anonymous source. It is clear the sender does not want to be traced.” Ralph said this without fanfare, apparently aiming to leave the group to its own reactions without filtering them through his own. He read: “Office Asia is in danger of becoming a priapic, chauvinistic pigsty. Template Jones is a menace and a threat to the firm’s image, purpose, and culture.”

Silence followed, but expressions rioted. Ian took on the stern look of an inquisitor. Martha turned her hands upward with a questioning frown that asked, as if to some higher power, “What now?” Art nodded, Of course. Howard squinted, furrowed his brow, and stared into empty space. Ralph retained as blank a look as he could and held his tongue. (Among other things, he was trying to act on Duncan’s suggestion that he learn to follow and bystand more, especially in difficult conversations.)

“Who in hell is Template Jones?” As usual, Martha broke the silence.

Howard dropped all facial affect. With admirable calm he explained that Template Jones was a Wall-Street ex-pat who, having left with millions and wanting to turn his mathematical genius to a noble cause “like ours,” had sought out Howard, and Howard had hired him. “TJ” was now “taking the lead with investments and is doing spectacularly well. You must have noticed from my financials.”

“With your permission, Martha,” said Ian, without sarcasm and carefully trying not to antagonize, “I’d like to get some background on this from Howard. Howard, what more should we know about this Template Jones?”

From there, the discussion at the meeting had passed through three basic phases, which Duncan identified for Ralph afterward in their private debriefing. Throughout the three, Howard was naturally center stage, having to explain, react, and defend. But notably, it wasn’t Ian from whom Howard needed to defend himself. Ian made it clear from the outset that what he wanted was information, not defense, justification, or rationalization; and remarkably he made no direct reference to the damaging allegation in the e-mail. Almost flaunting his fairness, he kept his infamous severity in matters of possible wrongdoing “out of the room.”

Phase one centered around Ian and Howard. In a quiet, nonaccusing, information-seeking voice, Ian questioned Howard, who said that TJ was a bit odd, but brilliant. “But his private life is his own business—that’s how I run my show.” According to Howard, TJ kept to himself in their Asia office, except for the long hours the two spent together when Howard flew over, and on their daily phone calls when Howard was back in the States.

HOWARD: We work hard and well together. We set the bar high, and others jump.

IAN: Do people seem satisfied?

HOWARD: Well, I’ve seen nothing that would result in an e-mail like Ralph just quoted.

IAN: I didn’t ask that. But tell me, when you are swamped with work, do people voluntarily stay on?

HOWARD: And no one has complained to me about anything.

IAN: I didn’t imply anything like that either.

HOWARD: Besides, I’ve just hired two men and three pretty smart, self-composed women in marketing and sales.

IAN: Good. Tell me about them …

And so forth. In this phase, as Duncan pointed out in debriefing, Ralph, Martha, and Art had remained on the sidelines, per a request from Ralph. “Which was smart,” Duncan added. “Then remember how, when Ian was satisfied he’d learned all he wanted, he sat back and nodded? And your onlookers were puzzled.”

“Me, too,” said Ralph. “I was also confused.”

“Me, I thought Ian was masterful,” said Duncan. “He followed an opposer stance with a clear move sequence. That’s a surprising Ian we’ve not seen before. I suspect the maneuver caused Howard to reveal more than he intended. Structural dynamics would say that Ian was all active bystander, asking Howard to do all the talking, the moving.”

The second, very different phase had featured Howard with Art and Martha. Martha had spoken with the opposer edge she customarily flashed when interacting with Howard—but in her favored language domain about caring, intimacy, and connection.

“And, Ralph, you must have noticed the distinct change in Arthur,” said Duncan. “He was at his evenhanded best—at ease, more energy and spirit, but effectively in control of his balanced behavioral repertoire. When he had to, he would even oppose Martha, inoffensively getting her to back off so he himself could continue to engage Howard on his own terms. The language Art and Martha used—that’s what I was tracking as well as the action structure—was distinct from Howard’s and, if you listened carefully, from each other.”

About the third phase of the inquiry as Duncan broke it down for Ralph, he said, “You, Ralph, were the person I noticed. In the first two phases you’d done your assignment well—following and bystanding. That was helpful to your team members who were probing in those first two phases. You added a useful sprinkling of your usual strong and frequent moving. (When you rain ideas down on them—oh, yes, you do that—they may feel more diminished than informed.) As for any of the scary opposing you sometimes do when one of your pet ideas is thwarted—you held that in check. In phases one and two, you were earning your A.”

“Then I lost it a bit, at the end,” said Ralph.

“Yes. When Martha steered the conversation to the ‘alleged threat to your firm’s purpose and image,’ the room became a ring, and you leaped in swinging. You said, ‘Things like that are never local, Howard. They are freakin’ fodder for a voracious rumor machine. Our purpose? What do you know of it, really? It’s the money community that matters most? What about the moral community?’

“Ralph, you were still throwing punches when Ian stepped in and refereed a stop to a one-sided fight.”

“Okay,” Ralph conceded, “you’ve got me on the ropes. And given me a lot to think about. Can we change the subject?”

So they did—to a brief recap of each team member’s preferred domain and language.

• • •

DUNCAN: Ralph, I want you to focus now on the last ten minutes of the meeting. You were rather strange, not your usual direction-giving, optimistic self—more like a grand inquisitor. You seemed to be questioning each one’s commitment to the firm’s larger purposes—perhaps triggered by Howard and the Asia affair. In any case, from the sour taste it left, I’d say they felt diminished … that you were disappointed in them. What’s going on?

RALPH: Do you think I have the right team? Sometimes I feel like I carry too much of the load. Work, travel, Sonia’s really bugged about it, I know. She catches me getting out of bed and says she feels abandoned, wants to know what I’m doing getting up at 2:00 AM.

DUNCAN: What are you doing?

RALPH: Oh, sneaking in a little more reading on clean energy science, Googling the competition, analyzing portfolios …

RON STUART: NEW HELP FOR RALPH?

After that debriefing, Ralph began to think more seriously about a certain recent contact he’d made with someone currently lower down in the ClearFacts ranks: Ron Stuart, a lad of thirty-four who insisted he felt old, fearing we would “run out of time before the earth either burns or drowns.”

Ten years ago, Ron had finished both his Princeton liberal arts BA and an MS in chemical engineering and quickly joined a Chicago-based solar energy firm, which he soon left to join a start-up that was recently acquired by ClearFacts. At the start-up he was known as a self-motivated, standout star going beyond the call of duty to keep abreast of where “smart money” was being invested around the world in green science and tech. His overriding goal was to make a contribution to the problem of global warming—a cause he would all but die for, according to Lani, his charming intimate partner and “bride in waiting.” It was Lani who’d suggested Ron go to the source and set his sights on headquarters. So Ron had sent Ralph the following e-mail:

… Investing in renewable energy is no longer a gamble. It’s a necessity. Companies all over are hiring scientists to work on renewable technology. University scientists and green environment entrepreneurs are teaming up. I have contacts in an Arizona-based solar energy firm, still in the start-up phase, that is interested in being bought up. They are receptive to some form of partnership with ClearFacts. They liked your HBR article. … With your reputation as a green energy visionary with impeccable moral standards, some form of marriage is a natural. May I request a meeting?

Ralph had been following the same developments and had been waiting for an opportunity to get into the act. In fact, Ralph’s Harvard Business Review article, “Building a Green Economy Is the Most Alluring Challenge of the 21st Century,” which Ron mentioned, was the same one that had drawn ClearFacts’s board to take Ralph on as new CEO. As for Ron’s words about marriage, Ralph smiled and wondered, Who does this guy mean to stand at the altar, the solar firm or himself? Either way, I need to meet him.

Their first actual meeting produced an instant professional bond. Ralph knew Ron at once for a passionate companion in arms. Both were committed to alternative energy in all its forms; both were information freaks; both sensed where the leading edges were; both were prescient and saw informed risk as the key to entrepreneurial success. Their conviction of a good match deepened over the course of two hours of talk.

That conviction soon became personal, too. Ron had earlier mentioned having been adopted. Now, when Ron complimented the company on the value it placed on diversity, thus opening the subject of his being African American and probing Ralph’s level of color-blindness, Ralph came back with an unexpected question.

RALPH: And so, growing up, did you date white girls?

RON: (Laughing) I see you’re no closet racist.

RALPH: (Laughing) No, just a competitive white guy. I had a black roommate at prep school—like you, better looking than me. Son of a bitch still is to this day. We go out for drinks and the best lookers size him up first. Tell me, Ron, what do you want?

Ron sensed that Ralph had carefully navigated this whole thing. When they parted, Ron felt a vague sense of warmth, of unfamiliar warmth—Ralph represented something in a father that Ron’s legal father had never provided.

At home that same day, Ralph had recounted this meeting to Sonia. Sonia had learned from nasty experience that all too often whenever Ralph seized on some new venture, he was likely to go too far. Instinctively, she felt that this “Ron” was one of those times, and her realization led to one of their familiar scraps. The substance was new, but the ritual was old. Ralph had wanted praise for finding someone, as Sonia had suggested, who could relieve him of the burden of “leading the charge.”

RALPH: But I’ve done just what you asked. Why aren’t you pleased?

SONIA: What did you promise him?

RALPH: Nothing, only that I would raise with my team the terms he asked for.

SONIA Terms? Or do you mean demands? Sounds to me no different from your “not promising” anything when you proposed buying that start-up just one month into your term at ClearFacts. Ian took you to task. He will again, I promise you.

And Sonia was right, as we shall see.

WHERE COACHES CAN GET STUCK

Often brought up in academic or therapeutic traditions, coaches (including Duncan and yours truly) always run the risk of getting stuck in or overusing the meaning domain. The academic environment prompts them to get hung up on theory, which might be called “ultimate meaning” because it attempts grand explanations. As a colleague once told me, “David, all of this stuff for you is like solving a tough detective story. Your mind never stops spinning its threads. Is that your notion of paradise?”

Maybe so. Coaches see great value in posing all kinds of questions and making potential connections that, through further discussion, might lead a leader to some urgent insight. They wonder what might be the origins of their clients’ propensities for the different domains. Genetic? Environmental? Shaped by happenstance? Chapter Six will explore the stories that shape domain propensity.

In theorizing, other coaches may be drawn strongly to the power domain as well. But whether the coach’s preference be affect, power, or meaning, the leader may be drawn to imitate the meaning preference of “the master.” Both leaders and their coaches need to be wary of this. In the context of their leadership work, certainly leaders must have a very strong hold of the power domain, and the other domains often serve them as well. But the objective of coaching or being coached should steer clear of the leader’s imitating the coach. Leaders need to develop all three languages, all three domains in ways that relate to their own direct experiences and awareness. In that way, skill in each domain will serve the leader’s own unique needs. Whether he or she ultimately retains or can fluently talk about the theory behind them may not be relevant at all.

| Domain | Rank |

| Affect | _____ |

| Power | _____ |

| Meaning | _____ |

- In work relationships

- In your most intimate personal relationships

Organizations generally rely on one domain or language system that is best suited to doing its work. What language does your organization expect of you? Does it match your strongest preference? If it doesn’t, have there been consequences? How do they play out?

Most intimate personal relationships employ a single language to enhance connection. What language domain governs yours? Does it match your personal preference? If it doesn’t, have there been consequences?

- What was your dominant language, the one you tended most often to use?

- Did it vary or remain constant?

- Were there miscommunications or clashes between members based on different language preferences?

- When the group was most stuck, were competing speech acts in play—for example, between a move in meaning versus an oppose in power?

- How did your own preferences affect whom you supported and did not support?

Notes

1. Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. New York: Bantam Dell, 2006. N/A.

2. Goleman, D. Social Intelligence: The New Science of Human Relationships. New York: Bantam Dell, 1995, p. 4.

3. Kantor, D., and Lehr, W. Inside the Family. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1975.