chapter THIRTEEN

A Model for Living

Man is born to live, not to prepare for life. Life itself, the phenomenon of life, the gift of life, is so breathtakingly serious!

—Boris Pasternack

On November 27, 2010, the New York Times business section ran this story:

[Last June] when Mr. [Gordon] Murray, a former bond salesman for Goldman Sachs who rose to the managing director level at both Lehman Brothers and Credit Suisse First Boston, decided to cease all treatment … for his glioblastoma, a type of brain cancer, his first impulse was not to mourn what he couldn’t do anymore or to buy an island or to move to Paris. Instead, he … channeled whatever remaining energy [he had into writing a book, The Investment Answer, with a friend and financial adviser] to explain investing in a handful of simple steps.

His goal was to puncture the myth that “if you’re smart and work hard then you can beat the markets,” and to make a statement about Wall Street’s moral slide from grace.

When he first landed at Goldman Sachs, the Times reported Murray as saying, “our word was our bond, and good ethics was good business. … That got replaced by liar loans and ‘I hope I’m gone by the time this thing blows up.’ ” In the wake of the 2008 financial collapse, Murray “testified before [an] open briefing before the House of Representatives, wondering aloud how it was possible that prosecutors had not yet won criminal convictions against anyone in charge at his old firms and their competitors.”

In June 2010, when “a brain scan showed a new tumor, Mr. Murray decided to stop all aggressive medical treatment,” concluding he had “balance in [his] life.” And although the first thing he thought about was his wife and kids, hanging around 24/7 waiting to die was not an option. His friend and coauthor, Dan Goldie, “had a hunch that writing the book would be a life-affirming task for Mr. Murray.”

Murray did not expect to reach his sixty-first birthday in March 2011, but still hadn’t bothered “memorializing himself with a photograph on his book cover or even mention[ing] his illness inside.” He was “willing to do just about anything to make sure that his message is not forgotten, even if he fades from memory himself.”

“‘This book has increased the quality of his life’ [a friend said], ‘And it’s given him the knowledge and understanding that if, in fact, the end is near, that the end is not the end.’ ”

Murray’s The Investment Answer was published in August 2010. He died January 20, 2011.

This chapter concerns a crisis in both life and career that besets many leaders roughly between ages forty-five and fifty-five. It should not be confused with what is commonly called the midlife crisis, though there are similarities and overlaps. I will call it the breakdown-breakthrough story. In it, the protagonist experiences a crisis or breakdown, most often beginning with external events, such as the death of a child or spouse, a fall from grace through downsizing, or a life-threatening illness, but sometimes beginning from within, an epiphany, sudden or crawlingly painful, that what was pursued in life has no meaning. Rising from the depths of despair, many leaders then reach a breakthrough and an accompanying change in the course of their lives.

Contracting a fatal form of cancer, Gordon Murray had a revelation. Knowing he was dying, he realized his life as a whole would have greater meaning if he contributed something more to the world—a lesson others needed to hear. For the short time left to him, he designed a life worth living, and left a legacy. He acted greatly when he felt forced to act.

But to act before one feels forced to do so is infinitely wiser. That, in brief, is what this chapter is about. In the latter part of it I will describe some of Ralph and Sonia Waterman’s efforts to build their models for living, together. To pave the way, I’ll discuss why models for living matter and how building them follows the same broad conceptual plan that works for building one’s leadership model.

THE MODEL FOR LIVING

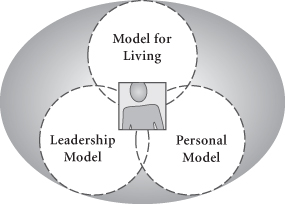

Figure 13.1 suggests that for a full life, you do well to see the self as the core of three distinct models, one that covers your personal predilections (the personal model), how you lead (the leadership model), and how you live (the model for living). Think of your model for living as a compass for your life overall, helping you stay true to your beliefs about life, leadership, and love. It is your means of reconciling your life as a leader with the other goals that, for you, are part of living a life of fullness and meaning.

Figure 13.1 For a Full Life—Three Models

Or think of your model for living as a scale or balance on whose opposite ends you can “weigh,” for example, the work side of your life—the product of your leadership model—against the personal side of your life, and decide what might need to be done to keep them in reasonable proportion to each other. If you know your model for living, you are able to make conscious and active trade-offs (and synergies) between competing demands.

However, there are always limits to reason as the sole basis for finding balance. For example, a leader may find herself caught between a personal model that places a high value on affect and a leadership model that emphasizes performance and achievement. Or another leader, having recently been warned of stress-related dangers to his health, may vow to ease up at work, but, driven by a childhood story that results in shame if he fails to complete every assignment, continues to put his health at risk. In instances like these, the leader will have to dig deeper than “balance” or pure reason to step into a life worth living.

The Perils of Success

As life centers more and more on work rather than the other way around, successful executives risk overdeveloping their professional selves and forfeiting the rest. Over time, insidious pressure shifts their orientation from their own lives to other things. One shortcut leads to another so that commitments to spouses, to children, and to relationship itself are bent and eventually broken. Life loses sensuality, and they become less and less able to recognize beauty and love. Work becomes the primary source of pleasure, accomplishment, and connections, and they all but forget that there could be time to reflect deeply on the nature of things.

Disturbingly many executives tell themselves that in the current climate “they have no choice.” Once this belief takes hold, not only does it become self-reinforcing, but their models start to be built around defending that belief rather than in resistance to it.

At the same time, the natural entitlements of achievement—status, power, and money—can make leaders more vulnerable to simply pursuing “more” while actually forfeiting life. High corporate status sets an individual above “the masses,” among “the elite.” Power—in the form of role advancement and advantage over people—also grows, particularly in “across” (peer) and “down” (subordinate) relationships. And money is a payoff (perhaps the best) that follows from status and power.

As leaders are bound to agree, status, power, and lots of money are not evil in themselves. However, together they unite in a circularly reinforcing structure much like the ones that make organizations or individuals vulnerable to moral slides. Most individuals are susceptible to the status-power-money structure, and at its edges echo some of childhood’s most enduring and painful themes: failure, poverty, rejection. Being inside the structure, in the “inner circle,” buffers the terrors those fears can bring, but as that happens, leaders can eventually become trapped in an endless pursuit of “more.”

The Time Dilemma and Temporal Anxiety

Extreme time dilemmas make it even easier for many executives to overlook the trade-offs they are making as leadership work swallows the rest of life. I use the term temporal anxiety to describe this tortured relationship with time. Many would give an arm and a leg for a few extra hours every day. They are always running from deadline to deadline, crisis to crisis, always short on precious time. They rely on new gadgets to save time and then spend inordinate amounts of their time saving time. They go to sleep anxious about what they haven’t done and wake up anxious about all they have to do.

Temporal anxiety impels an overworked, rushed executive to forgo the genuine pleasures of love and relationships in favor of more work, more effort, more hurry. Addressing that anxiety becomes a sort of pleasure in itself. He may not even notice what else he is missing because the intoxicating sense of flow, the “high” associated with measured time, pushes love, intimacy, and connection off the calendar.

MODELS FOR LIVING AND THE BREAKDOWN-BREAKTHROUGH STORY

Mature and aging individuals are likely to examine their model for living only when it collapses under the weight of many forces. Various crises can bring it on: a spouse falls ill and dies; a fortune is lost through risky investment; a powerful mentor is revealed as corrupt; the company is sold, derailing a fast-track career. Suddenly a lifelong way of doing things makes no sense at all. Work that once energized now begins to enervate. These kinds of natural but unsettling life events cause underlying questions to surface with resounding power:

For some leaders, these questions and related experiences lead to a breakdown from which recovery is slow. In time, most rebound, often having to claw their way back from the depths of despair and make dramatic changes that alter their lives. For them, this story is one of crisis and redemption—a breakdown-breakthrough story. The result is a more complete sense of who they are, what they stand for, and who they want to be.

The leader’s midlife story, therefore, has the quality of struggling to come out of the shadows, of dispelling the illusions of childhood and creating a new contract with life and with an organization. It is often a crisis of meaning: “Has my life really meant anything?” But underneath the profound questions about meaning lie the more fundamental questions of love: “Have I given or received love in my life? Am I happy with, do I feel good about [love] the person I have chosen to be?”

Building a model for living can clear your path to “breakthrough” by creating a sense of foundation and purpose. Begun before the worst arrives, it preps you to wrestle with these inevitable questions. Keep in mind that too often an earlier choice of a way of life was actually made after other life activities were in place, like a kind of accessory. Having a model for living means designing a life and a way of life that, in reality, you are starting to live—now!

Leaders, I am saying, must not stop with having a model for leading. At the end of the day, your model for living is an answer to the question I encourage all future leaders to pose for themselves: How shall I live? Among all other things, becoming a beautifully integrated whole means examining the interaction and causality between that question and How shall I lead?

BUILDING A MODEL FOR LIVING

Since the youth-driven revolution in lifestyles that began in the 1960s, countless writers have published often spirituality-coated guides to happier living. Some, like The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment (1999) and the more recent Eat, Pray, Love (2006), have erased all social boundaries and educational levels in their widespread appeal. To build the model for living I am suggesting takes a more systematic approach than these popular varieties. Indeed, designing a life worth living is little different from building a leadership model: it is highly personal; it is done in three phases—imitation, constraint, and autonomy; it is subject to growth in stages over time; and it, too, is best done under the guidance of a coach.

The Practice of Timefulness: A Must for Leaders

A useful tool in this endeavor is my book and structured diary Alive in Time, which redefines the experience of time and presents guidelines for keeping a diary designed to maintain consciousness on a daily basis of time’s unsurpassable importance to “having a life.”1 As we shall see, no life has meaning if it fails to grapple with time—every entrepreneur and every other consciously aware individual has come up against the fact or terror of mortality and its illusory ties with the experience of time and how to live in it. Alive in Time began as my own way of dealing with such matters for myself. Not a book about scheduling your day to death and not about time management, it provides the tools for the development and practice of timefulness, an intelligence we can apply to stretch, enrich, and modulate the experience of time. Most of the book is a vehicle for keeping a diary, including quotations, images, and other prompts for freestyle journaling around the central question of whether you may be squandering time when you think you are saving it. You can use Alive in Time as is or as a basis for designing your own similar resource. I’ll say more about this book later in this chapter.

As in all model building, a model for living also requires some work on the meta-model.

Theories of the Thing, of Change, and of Practice

Your model for living’s theory of the thing is an assembly of the principles on which you have built your life, whatever they may be: One should never compromise that which keeps one whole … Never cut short the time for love … Be kind … Building a legacy is a critical aspect of what we are here to do … Hard work is a virtue in and of itself … Humanity is defined by its compassion … Joy is just as important as hard work …

These principles represent fundamental questions, such as “What is happiness?” and their answers for you. In pursuing the answers, you begin to more actively converse with yourself about happiness than perhaps you have done in the past. The story of the life you want to live is your personal manifesto. That story is a work in progress, but the essentials in your theory of the thing steady the narrative while you continue to write toward the future.

For my theory of the thing, I found these four books most worthy: Tuesdays with Morrie (Mitch Albom, 1997), The Examined Life (Robert Novick, 1989), The Music of Silence (David Steindl-Rast, 1998), and The Needs of Strangers (Michael Ignatieff, 1984).

Your theory of change takes on the challenge of how to maintain commitment to your principles in the face of competing demands. It tackles the difficulties of how to lessen the gaps you see between your theory of the thing and your lived experience. It often includes recognizing patterns in your current theory of practice and facing your fears about doing things differently. These fears frequently originate in the ambitions and sensitivities of your leadership and personal models. Your model for living’s theory of change plays in the space between the other two models and deals with how to balance them.

Your theory of practice states those actions you intend to take and be known for that will convey your principles to others in the world. What will you do and, more important, not do, that will truly reflect your model for living? This implies the important step of identifying the gaps between how you are currently living your life and how you would act in the life that you want to live. Conducting this “gap analysis” will focus your efforts at bringing your model for living to fruition.

For my theory of practice, I focused on two phenomena, time and moral decision making and behavior in all aspects of my life. Stephan Rechtschaffen’s Timeshifting (1996) provided useful bites that led to my book cum structured diary, Alive in Time, which conceives of four sorts of time among which one may shift: measured time, which is necessary for getting things done; present time, for maintaining an awareness of all of my senses; reflective time, for keeping all life decisions in line with my narrative purpose; and contemplative time, for cultivating and expressing compassion for the less fortunate and for the world in all its troubles. When I keep my diary, I am alive in time. When I do not, I am all but dead.

Rest assured that as I created my model for living, I also made my way through its phases of imitation, constraint, and autonomy. There are limits to how much anyone can further spell out exactly how to go about creating your model for living. In the rest of this chapter, I sketch out some of the dialogues and events that took place between Ralph and Sonia, who recognize that they are creating two separate models for living that will ultimately also feed into a model they can create together.

RALPH, SONIA, AND A LIFE WORTH LIVING

Not every leader has a Sonia in their lives. Sonia is a character but also a symbol of that “other,” be he or she lover, friend, parent, sibling, or colleague, someone who has earned your full trust, someone with moral judgment clearer than your own, someone who tells you uncensored truths you do not want to hear. These functions need not even be embodied in one person, but to design a life worth living, you must have these functions available to you.

SONIA: Let’s pretend I’m the CEO here. I’ll set the agenda for this team today, and I’ll be responsible for seeing that disruptive attitudes and private agendas do not get in the way of the work we must do to come up with a three-in-one model for living: ours, yours, and mine. I mention mine last to impress you with the fact that I knowingly made an inequitable deal when we married, a deal I willingly and lovingly signed on to in full compos mentis, a deal I now want to revisit, a deal I must rescind. Until now I’ve been your sidekick, Tonto to your Lone Ranger. How about you become Caesar and Anthony to my Cleopatra—without the murder and suicides, of course?

RALPH: Ah, Cleo, less “beautiful” than a cunning seductress.

SONIA: True, but a more powerful woman than any woman and most men of her time.

RALPH: Okay, I’m as captivated by you as both those guys were by her. I put myself and this journey entirely in your hands. I assume you have a plan?

SONIA: I do, but not so fast. You can’t lull me into complacency by what could be feigned compliance. We both know I’m a controlling bitch at times, especially when I think you are out of control and you don’t know it. Your words just said one thing, but your voice said another.

RALPH: And it said?

SONIA: It said, “Here she goes; sounds like another takeover.”

RALPH: And?

SONIA: And it is. (Both laugh.) That said, here’s my plan and a difficult tag-on condition. My rationale for this “takeover,” Ralph, my love, is that you’ve been brainwashed, a victim of time’s depredations, robbed, plundered, ravaged, and fooled into thinking you’ve outfoxed the reaper. No one outfoxes the reaper. Read Duncan’s stuff again; read Alive in Time. You look awful, not your old self.

RALPH: Thanks. I’m just tired.

SONIA: You’re tired from leading an organization, scouring the world for innovative green opportunities, leading two teams, and working on your leadership model like a graduate student meeting a thesis deadline, gassed up on No–Doze or Ritalin. You’re not only tired, you’re not even only exhausted: you are sleep deprived! Let’s face it, when your body fades, and, Zeus willing, we’ll both be around when it does, I want all that the serviceable body and that bountiful mind have to offer preserved. You are destroying them.

RALPH: Okay, I’ll take the bait; just don’t pull too hard on your line. What are you fishing for?

SONIA: Let’s begin with our Italy trip. Remember it?

RALPH: Sure, our epiphany.

SONIA: Yes, it was an epiphany because we entered another time space—and I’m not talking about meridian time zones. I loved being there with you, but it was a different you from the busy you. I don’t want to circle the globe every time I yearn for slow lovemaking or solitary time with you, the complete you, within reach. I want to look up from a book I’m reading and know where you are. When I read On the Road and Blindness, two books I could not put down and dreaded to pick up again when I did, and did not have you anywhere near in time or geography to share my dread, I felt lonely and could not bear the waiting.

RALPH: (Irritated) You’re no sit-at-home, Sonia, not one to die on the vine.

SONIA: (Picks up a book from a nearby table, extends her arm, and drops it flat onto the wooden floor) Do I have your attention? This is not about me. We know I am fully capable of taking care of myself. It’s about you and time. You asked me to read Duncan’s “Model for Living” material, and I did. Lapped it up, as you did. What impressed me most was the stuff about time. I’m having this out with you now before we begin, because if we are not on the same page with it, unless we give that feature of this model thing the highest priority, it will all come down to pure posturing, just a lot of (and I do not beg your pardon) bullshit.

RALPH: Are you deliberately picking a fight with me? Why? I’m really with you in this.

SONIA: Well, if it isn’t apparent, yes, I am. I took the liberty of speaking with Duncan. Duncan knows you, in that “other” context. I know you better “here,” and I’ve learned a lot about who you are “there.” Duncan was a bit suspicious of your unquestioning enthusiasm for this whole project, wanting to do your leadership and life model at the same time, but was taken in; he realized that he had been, after I pointed out how, when you are really, really under the gun, you press harder, race faster, push beyond limits, and take on more, not less, and then compliment yourself for managing to be “the last one standing.” If you do not find a better way to “expand your repertoire” as Duncan says, unless you find a way to get done what you absolutely need to get done while at the same time being able to be with me, and with yourself, a whole self, “alive in time, not dead,” as that book [Alive in Time] says, all this model building will come to nothing. I would feel more assured that something new and special will come from this exercise if you questioned yourself, your own doubts, not about the wisdom of the program, but about the human possibility of pulling it off.

Now Sonia had Ralph’s full attention. He knew how easy it was to forget time journaling, especially with the tricks of the mind that he invented to forget its existence and to surrender to temporal anxiety. These facts were the basis for the “doubts” he reluctantly admitted next.

RALPH: Well, I do have doubts. I have many doubts.

SONIA: Ah, finally, admitting fallibility, admitting you have doubts that you can do it all. Having doubts doesn’t forecast failure. It increases the possibility of success.

RALPH: A cheap cliché, but true.

SONIA: (Relaxing at last) So, before I present my plan, let me say this. I, too, have doubts, but they could not be assuaged until you admitted yours.

RALPH: Fine.

SONIA: And now for my plan.

Sonia’s Plan and a Hard-to-Keep Condition

SONIA: My plan is to do this at a gradual pace, reflecting separately and together, and to stop every so often, go elsewhere, out of work’s long-armed reach—let’s say, to lovely out-of-the-way inns.

RALPH: Agreed.

SONIA: No computer. No briefcase bulging with unread reports.

RALPH: (After a very long pause) Agreed.

SONIA: Sorry, but I’m not quite done. Working together, we’ll know when to schedule these three-day retreats—

RALPH: Three days? When will I do my job?

SONIA: Yes, three. I’ve chosen inns for all seasons, skiing, hiking, swimming, all off the beaten track, and for being alone together.

RALPH: You’ll have to teach me how to enjoy solitude. You probably have a long list of books to read.

SONIA: (Feigning embarrassment) I do, and you’ll find Intimacy and Solitude at the top.2

RALPH: You must know you’re being a stuck mover.

SONIA: Yep, and I hope you’re not being courteously compliant (nervous laughter). In effect, we are testing the model’s basic premise, which is that you will be more, not less, productive; more, not less, creative.

RALPH: What it doesn’t say is how hard it will be. In fact, what we read makes it sound easy. We know better.

Two months later, Ralph and Sonia had arrived for a long, late-summer weekend at Anchorage by the Sea, an oceanfront resort in Ogunquit, Maine. After they had moved through the “easy work,” learning how to enjoy activities undistracted by minds full of work obligations, Sonia turned on Ralph with a flat accusation about things that had been going on at home. Sonia’s unarticulated fears were validated: Ralph was taking middle of the nighttime breaks from sleep to “catch up.”

SONIA: I know what you’ve been up to.

RALPH: Every moment?

SONIA: You’re guilty of purloined time.

RALPH: You mean you caught me in the act?

SONIA: I did. You’ve been cheating on this “time” stuff, working all day, spending more time at headquarters, pulling back on our time at home.

RALPH: Well, a little.

SONIA: Which is bad enough. You’ve also been slipping out of bed at night to work on the computer. Three times last week. I’m a light sleeper. When you leave my side, I know it. At first I thought you were snacking or something. By time three, I got up and peeked. You were working.

RALPH: On my leadership model.

SONIA: So it’s worse than I thought. First, you broke our agreement about measured time, of doing only what was absolutely necessary.

RALPH: So I slipped. I’m guilty of temporal anxiety.

SONIA: No, you lied to me, a violation of your moral contract and ours. See the contradiction? Moral leadership my ass.

RALPH: Oh, Sonia, show some compassion. That damned theory part is harder than I thought.

SONIA: I know Duncan is not pushing you on this.

RALPH: No, it’s me. I’m sicker than I imagined. I just don’t like to fail.

SONIA: Okay. And (sarcastically) I reap the benefits.

RALPH: How about if I give you my word right now that I’ll take the time diary more seriously?

SONIA: Is that a pledge?

RALPH: It is.

SONIA: For my sake? Ralph, don’t you get it? Unless you do, you’ll be failing at “time,” a required subject, not an elective in this school of life.

Ralph not only made the pledge but kept it, with lapses that became less frequent as he began reaping the benefits of journaling momentum.

Sonia Hits a Wall

It was fall now, and Sonia and Ralph were on their second retreat at the Deerfield Inn in the countryside of western Massachusetts. Sonia was not fully enjoying this traditional country inn, built in 1884. She had been scratchy for the first day and into the second. Ralph concluded it was “women’s stuff” or a mild illness that would pass; it didn’t.

When they settled in to talk after their walk amid the dazzling spectrum of color in the woods, she declared she was in crisis. She was thinking of her narrative and had gotten in touch with the fact that her purpose in life was escaping her. Her adult story had begun with the birth of her first child and had continued through her divorce and deadening routines for a couple of years, followed by her falling in love with Ralph and agreeing to follow him from one job to another. Now that story felt dead in its tracks. When they’d met, she’d been like Jill Clayburgh’s Erica in An Unmarried Woman: single, having learned that she didn’t have to define herself through her relationship with a man.

SONIA: I learned that early, when I was divorced. I have carefully modulated my dependence on you. I have fashioned a life for myself; it has meaning enough, but there is a basic issue that needs looking at and correcting. While I’ve never put it in these stark terms, in these years, when you have been preoccupied with your world, having my own separate parallel life has worked. I’ve kept busy by serving the community, and I’ve been well rewarded.

RALPH: Not as much as you’ve deserved.

SONIA: Wait. I’m not clear yet how to say this; you and your narrative have been center stage so long that I no longer have a narrative of my own that really suits me. I mean, I was satisfied with our “we”; it seemed intact and strong, but my story, the story of “me,” the more I’ve thought about it lately, the less focus—and less future—it seems to have.

RALPH: You have something new in mind?

SONIA: An adjustment.

RALPH: Spill it.

SONIA: No. I want to work this out by myself and then with you—first what I want, and then how that depends on you.

RALPH: My work life, you mean?

SONIA: No, I mean our designed life. I’m a fool if I don’t figure out whether I want to continue our present terms of agreement. Will I be content if I do? For how long? Don’t get me wrong. I’m not questioning you. I’m questioning myself, and I have no easy answers.

Signs of Change?

Three months later for their next retreat, Ralph and Sonia were at the Three Stallions Inn in Randolph, Vermont—ski country. Sonia preferred downhill; Ralph, cross-country and snowshoeing. But before settling down to some serious skiing as part of the business of rediscovering how to live, Ralph sought Sonia’s counsel.

RALPH: I have something to talk about. I’m confused, and need your perspective.

SONIA: I’m listening.

RALPH: Last week, I broke off from work for a fifteen-minute spin along the river. I’ve been doing that since you caught me at my surreptitious nocturnal affair with my computer. I’ve been faithful to the diary for many weeks, and the damned thing works. Research on my model, now that I’m not pressing, is coming along fine. But after my walk, I had a strange experience. I felt buoyant, energized; but in the elevator, a feeling of profound despair came over me. It contradicts everything else going on in my life right now, most of it good. All is quiet, relatively speaking anyway, on the ClearFacts home front, and I don’t remember when I’ve loved you more than I have since we took this thing on together.

SONIA: That’s good to hear. Go on.

RALPH: Entering our office suite and making my way back to my own office, I passed the others as usual, nodding or waving to each (we tend to keep our office doors open). They were all the same people, but suddenly I didn’t recognize them. Who I am in relation to them was out of focus. I wasn’t hallucinating, or anything like that, but they were all strangers, and I felt like an alien. Duncan was waiting in my office. I never said a word to him about it. Whatever it was, it had passed. Any ideas?

SONIA: I’m delighted.

This began a long conversation, ending with a simple, accurate insight: this strange experience was a sign that Ralph was undergoing change, nothing more. Such experiences signaling change are fundamental to successfully reaching a goal of one’s model for living, that of having it both ways: a meaningful work life and satisfying personal life combined in one. Most successful people are a bit obsessed. This obsession is part of their recipe for success—a clear goal, a harsh self-discipline, and an obsessive drive to succeed. And as busy people, many carry additional psychological baggage, heavy enough to sabotage their full commitment to designing a full and integrated life.

Busy leaders, under time’s unwavering “mandate” to get what is important to them done and to stamp down what gets in the way, live in (mainly unacknowledged) fear and rock-bottom anxiety. These worrisome emotional states can be stoked by any of the universal or specific themes I cited in Chapter Eight that individuals find—or, rather, make—relevant and thus useful in their campaigns of denial. Two such themes are particularly common: fear of dying prematurely and fear of being a fraud—that is, of not being “who” or “as good as” they say they are. Neither theme finds a comfortable home in a leader’s consciousness. It is far easier to keep running. It was for Ralph.

Sonia’s Dilemma—Connection Versus Independence

What suffers most in the lives of busy people is real connection outside work. Like the mates of most busy people, Sonia carried a special burden, that of patching together a life beyond work, playing taskmaster and minister of culture as a general rule, and police force when promises were broken. She played all three roles with well-aimed determination. (We saw the couple’s dynamics in the earlier dialogue: her stuck mover and his courteous compliance and covert opposition.) Thanks largely to her, the Ralph and Sonia in this story have more than a fair share of domestic connection. And their sex, again largely managed by her “altogether willingly and voluntarily,” remained more vital than is true of most post-honeymoon couples.3

We must not understate Sonia’s immense contribution. The “condition” she initially held out for and which Ralph accepted—that they go off periodically on retreats in beautiful surroundings with opportunities both for play and serious work on their models—was itself a stroke of designed genius, a kind of spring training for the real thing.

But the general ongoing dynamic between the two, it seems safe to say, is not the best formula for them in designing a life worth living, as we define it; this life risks failure unless these roles, both equally subversive, are abandoned. The stuck mover must be relieved of sole responsibility for providing direction, and the covert opposer must undergo correction, wanting to pursue fuller life on his or her own impetus. Until Ralph stepped up to the plate, Sonia’s own developmental readiness for an integrated life would remain incomplete and stalled.

When people begin to examine their lives, as they are urged to do here, it is not without cost. In asking questions that must be addressed though not necessarily answered (especially the unanswerable ones that raise what may be the hardest question of all, Does my life have meaning?), they often come up against a wall, as Sonia did.

Ralph’s Corrections and Sonia’s Wall

For their next retreat (and for the first time since courtship), Ralph made the arrangements. Sonia, in a rare state of agitation, had tipped him off. She needed quiet space, with time to work on her life and on the problems she was having designing it. To his surprise, he was looking forward to this retreat with a mind swept clean of business-related details; knowing that his enthusiasm was about him, he kept his thoughts to himself. This was her time.

He made arrangements at Rabbit Hill Inn in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, a 1795 inn, billed in its brochure as a “tranquil place,” “an oasis of unparalleled comfort and a perfect destination for intimate getaways.” They took long walks in silence. Her hand felt small in his. He’d rarely felt so protective, and never had that felt not only good but so right. In front of a wood-burning fire, sipping wine, he kept his tongue in check, waiting, proud but not overly so of the changes (“corrections” he called them) in his behaviors (not relying on Sonia to arrange the retreat, relishing rather than tolerating the silences he knew she needed). All signs were that she had come up against a wall.

Each had a book in hand. Occasionally Sonia would look up from hers, indicating that she had something to say, but then return to reading and silence. Then suddenly she spoke of her daughter by her first marriage, who was now away for her first year of college:

SONIA: You must make a new effort to connect with Emily. You used to drive her crazy. She is a very disciplined, straight-thinking young lady. A bit prissy, perhaps, but tolerant generally, and she admires you and what you are trying to do in the world. (Ralph waits, nods only slightly, says nothing.) You almost lost her when we started out together, but she came around. You won her heart, but barely.

RALPH: And she won mine.

SONIA: But she doesn’t know that.

RALPH: What must I do?

SONIA: Convince her. I leave how to you, but she desperately needs a father. (More silence) I think we need a second home, a retreat of our own.

RALPH: I’m a step ahead of you. I have two real estate agents looking, one near the ocean, the other in the country. I think I know what you’d like, modest and removed, and not wired; but let’s wait and see.

Their conversation continued a long time. At times she said things with no context. Here is a sample:

• • •

As time went on, Sonia’s comments grew darker.

SONIA: Thank you for listening. I’m ready to talk now. My trouble is, I know who I was, I think I know who I have become and find myself rejecting it, and I have no clue as to who I want to be for the rest of my life.

(She pulls out a scrap of paper with words from the model-for-living material—a list of the causes of “breakdown.”) For me, it is (reading) “a lifelong way of doing things suddenly makes no sense at all.” “ ‘Work’ that once energized begins to enervate.” For me, it is worse than that. At times I feel like I’m dying.

RALPH: You are hinting, not quite saying, that there is something wrong with our lives.

SONIA: I am, in one sense. You are, in one respect, like your father. He was peripatetic because he left such a bad taste in every parish; he had to move. You move because you set goals, reach them, and then get itchy. I don’t think you will leave ClearFacts soon, but with you, there is no knowing the future. So where does that leave me? What is my place in this design? My relation to you, my agreement til now, has been to follow you until you found a place where you wanted to be. You appear to have found one. Still, I’m a fool if I don’t figure out whether I want to continue our present terms of agreement. Will I be content if I do? For how long? Please do not get me wrong. I’m not questioning you. I made this deal with my eyes open, in fact in rapture of you. I’m not questioning you; I’m questioning myself. And I have no easy answers. (Wisely, Ralph says nothing. His quiet presence seems to be all Sonia needs. A long silence follows.)

Thank you again. I do expect that I will come out of my “breakdown” with a “breakthrough.” That work is mine alone. I’ll ask for help if I need any.

A Shared Narrative Purpose

Two months later:

RALPH: I’ve learned more about you, me, and us in the months we’ve been doing this exercise than I have in the eight years of our marriage. You said that you’ve had a breakthrough.

SONIA: I have. When I became pregnant, I quit law to raise Emily. I never took the bar. I will bone up and do it soon. I would like to join you.

RALPH: If that means we can begin working on our joint narrative purpose, I couldn’t be happier. It’s lonely up there at the top.

SONIA: And nothing would please me more than converging our parallel lives, and this is tricky, without losing my autonomy. After that sleaze Howard Green was caught making risky investments and cooking the books, you became fixed on the subject of fraud and on moral character, an antidote for this pernicious disease. The law let Howard off the hook. The law has let many on Wall Street who are responsible for the same practices Howard and Jones were into off the hook.

RALPH: At least it gave impetus to my focus on moral action.

SONIA: And since you took up your cause, I have begun to do some reading on the subject. There’s this terrific article in the New Yorker: “What Good Is Wall Street? Mostly What Investment Bankers Do Is Socially Worthless.”4 The author says that “the history of Wall Street is a series of booms and busts,” and that “after each blowup the firms that survive temporarily shy away from risky ventures and cut back on leverage. Over time, the markets recover their losses, memories fade, spirits revive, and the action starts up again, until, eventually, it goes too far. The mere fact that Wall Street poses less of an immediate threat to the rest of us doesn’t mean it has permanently mended its ways.” It simply made me think. There are hidden but known forms of institutional immorality. I will study all such forms of poorly monitored ethics, some of which are criminal yet enjoy legal sanction. My job will be to find and expose them, perhaps in my own blog. This will bring me closer to your narrative, if you will let me. I promise not to crowd you.

RALPH: I am told that developing a shared narrative purpose is a journey in itself with plenty of pitfalls.

SONIA: There is much more to our narrative purpose than this, I know, but if ours are intertwined as I am suggesting, the rest will more easily fall into place.

Anyone who decides to design a model for living does well to anticipate bumps in the road and even unseen dark holes, as Ralph and Sonia have. If they decide also to tackle their narrative purpose, the pitfalls are even more perilous. Couples I have worked with are instantly drawn to the whole concept, but I have learned not to introduce it until much work has been done and they have the problems they came with well under control. Even then it becomes a difficult journey because it brings into question some basic assumptions they’ve had about life that they’ve not seriously faced.

Ralph and a Fear of Dying

This process of self-exploration wasn’t easy for Ralph either. When he was well along in his design of a life worth living, and was rolling along smoothly in establishing a relationship between his narrative purpose at work and in his life with Sonia, he came to an uncomfortable realization. It spun off of something Sonia had said at one of their retreats that he later took to deeper level. Sonia had likened his peripatetic career to his despotic father’s being driven from one parish to another. Ralph added his own insight: if he kept moving from job to job, he would not have to face his fear of premature death, a theme he cleverly kept from consciousness by his past and current lifestyle.

RALPH: My first surprise was that all this is anxiety inducing; not a fear of dying, but of dying prematurely, before having lived enough to let the Grim Reaper take you by the hand and go with a smile on your face.

Remember that strange experience of sudden despair I had? You were right: it was the beginning of change, the start of my course correction, which has held up pretty well since. I am working at a good, steady pace on my leadership model building. Also, I now know better how I can help others not stumble along without ethical or moral responsibility. I have set in place automatic alarms so that we at ClearFacts do not lose our ideals and our commitment to bettering the world. And whether we succeed or fail, I will just be satisfied working to get ClearFacts recognized as one of the hundred best companies to work for.

But I think my “strange experience” was a kind of near-death experience.

SONIA: Let’s spend a week living “as if” death, of one or the other, were drawing near. How afraid of dying are you?

RALPH: I’m not afraid of death; it’s dying before my time that scares the hell out of me.

SONIA: And that means?

RALPH: That means I’ve got a lot of work still ahead of me.

SONIA: We both do.

- Has my life really meant anything?

- How much of status, power, and wealth is enough?

- Have I given and received love?

- Am I happy with and do I love the person I have chosen to be? If I were to die tomorrow, would I be content that I have lived a life worth living?

- What implications do my personal and leadership models, with their gaps and shadows, hold for answering the emotional-existential questions?

- What help do I need in addressing those gaps? What assets will I be able to call on to address those gaps?

Notes

1. Kantor, D. Alive in Time. Cambridge, Mass.: Meredith Winter Press, 2002. Available through the Kantor Institute (www.kantorinstitute.com), or through Meredith Winter Press (www.meredithwinterpress.com).

2. Dowrick, S. Intimacy and Solitude: Balancing Closeness and Independence. New York: Norton, 1991.

3. Kantor, D. My Lover, Myself: Self-Discovery Through Relationship. New York: Riverhead Books, 1999. Available at www.meredithwinterpress.com.

4. Cassidy, J. “What Good Is Wall Street? Mostly What Investment Bankers Do Is Socially Worthless.” New Yorker, Nov. 19, 2010. N/A.