chapter EIGHT

Leader Behavior in High-Stakes Situations

When stakes are raised, how does your behavior change from how you behave in ordinary times—that is, in low-stakes circumstances?

Chapter Six completed our basic tour of the four-level model of structural dynamics as the four elements appear when life seems relatively normal. In this chapter and the next, we will see what happens as the stakes climb in the minds of members of a team like the one at ClearFacts. We will also see how our behavioral profiles predispose us to fall into certain negative personal behaviors when high-stakes events and conditions trigger powerful personal themes. At some point, every leader or consultant has to deal with these high-stakes problems. Whether or not you have probed deeply into Level IV (the level of story and identity), knowing another person’s behavioral profile will help you understand what that person is likely to do—and how you are likely to react.

“Stakes” lie within us. Although high-stakes situations can involve large amounts of money or even the fate of an organization, what makes the stakes high in structural dynamics is not the dollar amount or the magnitude of societal outcome. The “height” of high stakes is determined by what individuals are feeling and what powerful themes (originating in early childhood and late-adolescent stories) are triggered. Things that “push our buttons” can include other people’s styles, the voice they use in conversation, and their domain or language preferences. (Remember that by other I mean persons with different profiles and personal stories.)

This chapter should put you in touch with your own high-stakes triggers and help you see how to enable others to reach that awareness. It should also reveal the kinds of people whose profiles pull those triggers, and the pairings with those “others” that can send you both into circular action and reaction. It should help you consider, when your own reactions go unproductively out of control, how your behaviors may originate in the dark side of your own behavioral profile. But don’t be too quick to condemn yourself or others. Keep in mind that the drive and energy of our shadows are what mobilize, motivate, and drive both our best and worst selves in times of crisis—our light and dark sides.

MARTHA’S ERUPTION

Recall the two kinds of stories and themes to which Martha is particularly vulnerable: the undue use of power by others and others’ failures to tell the truth. At the weekly team gathering a few weeks after her return from Asia, she sensed strange goings-on during the “business and strategy” part of the meeting. Ralph was showing predictable signs of support for a new acquisition that had been recommended by Ron; but Howard—usually irked by any “good idea” from Ron—was saying strangely little.

Also surprising at the meeting, the decision to sell an acquired company that had failed came up, but received only perfunctory attention. No one asked what due diligence had failed to notice when the decision was made to buy. At that time, Ian had wanted to kill the move, but Ralph’s enthusiasm had eventually won the team’s support. Contrary to custom, Ian, rather than taking his usual “analyze the situation and learn from it” approach, waved it off with a gesture. Rather than saying “Let’s start with what I missed,” which was Ralph’s way of modeling the taking of responsibility, Ralph seemed distracted. Martha concluded that something other than what was on the table was going on.

To her it was as though they were all moving in slow motion yet tearing through business in record time. It was as if all present were gagged, unable to speak, or determined to say as little as possible. Something was in the air. By no coincidence, other rumblings sounded inside her, related to her own stories and themes: her continuing unease over Lance’s broken pact; her now revisited childhood sadness over her father’s mortifying protection of his wife’s infidelity; and her history-driven, fanatical urge to nail someone who wasn’t telling the truth. Right now that urge was aiming at Ian, though it would soon aim at Howard too.

At the shift to the “people and culture” part of the meeting, her inner smolder started to flare. At this point, she asked Ralph for a few minutes in the agenda, though she had not identified the subject. Ralph agreed.

MARTHA: Howard, I have a question: Who is this Template Jones?

HOWARD: He works with me, a kind of special assistant on development.

MARTHA: That’s pretty vague. What does he do?

HOWARD: What is this, an investigation? I don’t have to answer to you.

MARTHA: I’m afraid you do. I am HR director—

HOWARD: I went through your regional director.

MARTHA: That’s okay for a lower-level person, not for a major hire. That comes through this team, and finally through Ian.

HOWARD: I resent this. The team and Ian approved my last budget request. A big item was personnel increase. My office is growing, and showing impressive profits. TJ is helping me make that happen.

MARTHA: Needless to say, I am pissed. Something smells. Ralph, since when does a member of this team or any office director have the power and authority to make a decision of this order without team approval?

HOWARD: I do have it; I have been given wide decision range to grow Office Asia, which is the fastest growing of any.

MARTHA: Ralph? Ian? This is a key procedural issue. This is about decision rights. I want to know whether Art or Ron or I have the authority Howard has assumed. Where the hell is our touted transparency? What he’s done is irresponsible.

HOWARD: Don’t ever talk to me about irresponsibility. I work hard and I produce. That’s what leaders do.

MARTHA: You’re no leader in my book. Leaders guide; they do not bullwhip.

HOWARD: Wrong, Martha. What leader of note has not taken a whip to a dumb mule?

RALPH: (In a loud, cracked voice, almost shrieking) Whoa! Hold that cursed tongue, Howard! You sound like a slave-master. Not in this firm. Martha, you’re not in control. (Silence follows.) Sorry, I lost it. There is a blurry margin here. Why not put a stop to the wrangling you two get into and let Ian look into it?

RON: Martha, it’s clear that you, and you, Howard, both care about this company, in your own ways.

Thus Ralph, with much needed help from Ron, who was establishing himself as the team’s new best bystander, managed to quiet Martha down. At their post-meeting coaching session, Ralph aired his concern, and Duncan tried to explain what had happened.

RALPH: Martha’s on a warpath. Her hatchet tongue is drawing blood. I’ve never seen or heard her like this. You’d think they were enemies she’s determined to bury.

DUNCAN: You’re thinking linearly again. As you know, neither Ian nor Martha nor Howard nor you is innocent. You have to think circularly about what’s been happening in the recent past to understand what’s provoking her. She’s reacting and acting simultaneously. You’re not seeing it all at once, but the whole is there—a vicious cycle spinning out of control.

The Martha-Ian imbroglios and the more recent Martha-Howard donnybrooks that I have covered so far are more common than the professional literature has discussed. I will attempt to give a new perspective on these high-stakes situations and the counterproductive behaviors they elicit.

VOICES, THEMES, AND TRIGGERS

As a trainer, to help my trainees recognize structures, I often say, “See with your ears, hear with your eyes.” Earlier in this book I used mainly the metaphors of “seeing” or “reading” the room as a means of noting and naming structures. Now let’s switch to the “hearing the room.” Why? Because when stakes are high, hearing voice becomes central to diagnosing what’s going on. That voice begins inside us.

Our High-Stakes Private Voices

Unproductive, out-of-control behaviors in high-stakes situations begin within our own private negative attitudes toward others of different profiles. Our poor behaviors begin with our own private voices, which in turn are influenced by our own behavioral profiles.

Only when pressed are most people willing to express “incorrect” social or political views. We are social animals, after all. Wishing to survive, we do not usually say aloud all we think. However, in high-stakes situations, we express these normally silenced thoughts involuntarily, against our conscious wills. Drawn into open discourse, they vex and incite others to respond in kind. Thus communication in high-stakes situations often turns destructive.

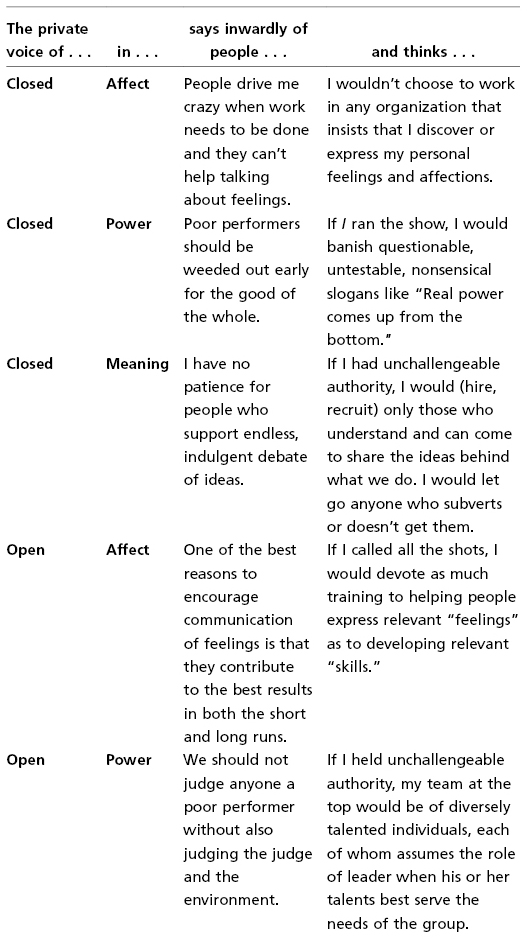

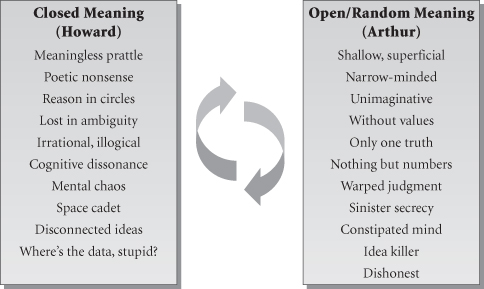

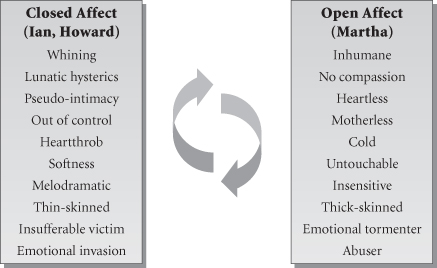

As our own private voices vary from those of others, behavioral profiles can help us sort out these differences. For example, the private voice of someone who is typically closed in affect differs from that of someone who is typically closed in power, and differs even more from, say, someone random in meaning. Table 8.1 briefly describes the differences among such private voices, ever present in our minds. Read it over and think about the differences you hear. Then think about what irritations become uncorked when, under the pressures of rising stakes, we inadvertently loose them on people (in boardrooms or bedrooms) who are truly, inevitably “other.”

Table 8.1 Private Voices and Behavioral Profiles

Attitudes such as those shown in the table prevail in both team and couple systems. When the stakes are raised, those attitudes can migrate from the privacy of our minds to full-scale verbal assaults that are fueled by personal themes. Thus theme becomes a central concept in structural dynamics.

Themes

When I turned to discussing personal stories in Chapter Six, I described the source of an individual’s resonant themes. By theme we generally mean a motif, topic, or subject that occurs in and brings life to various forms of communication—literature, theater, and film among others. In the context of structural dynamics, themes—especially our resonant themes—also bring life to verbal interaction in closely held groups of two or more people.

In structural dynamics, such themes predispose us to be catalyzed or triggered into strong reaction, often emotional in nature and negative in tone. The following is a list of ten more or less universal themes. When salient they can cause events to trigger most people into powerful actions or reactions.

Ten Universal Themes

- Fear of failure

- Fear of being unjustly seen as lacking character

- Fear of radical change

- Fear of poverty or loss of livelihood

- Fear of having one’s basic identity questioned

- Fear of being unjustly accused of wrongdoing

- Fear of being publicly humiliated

- Fear of being denied fundamental rights and liberties

- Fear of dying before one’s time

- Fear of being discovered as inauthentic—a fraud

Themes from the childhood stories (such as that of imperfect love, described in Chapter Six) accumulate and make their way innocently and more or less inconsequentially into everyday adult conversation, but in high-stakes discourse they erupt. What drives them to explode are the negative shadows we’ve attached to them (the hidden expressions of our fear that we are unloved or unlovable) and turn on ourselves or others.

I call the very high stakes themes that surface in live, high-pressure conversation toxic themes to emphasize both the extreme sensitivity individuals have to specific themes and the intensity of their reactions. Some thematic situations hit particularly close to home, often with deadly, venomous force and harmful or pernicious impact.

It is between couples and in closely held groups that toxic themes arise and do their greatest damage. In such groups, a toxic theme can escalate high-stakes behavior into disproportionately extreme attacks, sometimes physical, often with threats of divorce or rupture: “I want out.” ”I want a divorce.” ”Our professional relationship is over.”

People know their toxic themes when they see them. And when they do, they can plunge into such depths of despair that they feel they can never climb out.

What Makes Situations Personally More High Stakes

As I’ve just suggested, within an individual, some themes have more power than others; not all are equally charged with energy to arouse, provoke, disturb, and cause the person to be upset. A person’s high-stakes themes are strong in this regard. Look back at Figure 6.2, “Shades of Anger and Resulting Themes.” This hypothetical but empirically testable figure allows us to assign greater force (potential for arousal in the anger continuum) as we move along each thematic continuum from left to right. From years of clinical and training experience, I suggest three factors that can be at work: the degree of meaning, the love factor, and the ritual factor.

The Degree of Meaning

Most people feel confident recognizing this factor, which involves distinguishing between what is and isn’t low, high, or very high stakes for them. The issue here is identity: what matters; what “I” make meaning of; what touches “me”; and what triggers outsized reaction in me, toward the “other,” toward my real enemy, or toward my lover-turned-enemy. The reaction to my nemesis, that despised polar opposite who, therefore, defines me as his opposite, is greater still. Identity formation is ultimately a meaning-making activity, and the meanings we make of most things are, crudely enough, a Me versus Not-Me phenomenon.

The Love Factor

Lovers and spouses, those to whom we look for love—in a real or symbolic sense—have more power to influence our behavior than, say, mere friends or less important colleagues. Similarly, if we have some psychological necessity to please a boss (because he is a symbolic stand-in for a parent’s lost love), that boss will have more power than will, say, a peer. We burden these real or symbolically empowered figures with answers to the four crowning questions of love: Was I loved? Am I loved? Do I know how to love? Do I know how to be loved? When one or more of these questions are involved, the stakes invariably rise.

The Ritual Factor

Virtually all people in close relationships will quarrel. The inevitability of “difference” guarantees it. Of these quarrels, one will surpass all others in meaning because it crucially engages one or more of the four basic questions about love. With repetition, this often “vicious cycle” quarrel takes on a life of its own. In time, it “owns” us. In Chapter Two, I called it the ritual impasse, and in Chapter Six you saw it rise between Martha and her husband, Lance. With repetition and unsuccessful resolution of the conversational impasse, the reaction time it takes that couple to trigger each other has gotten close to zero, and the effect becomes more and more explosive.

We tracked the themes fueling Martha and Lance’s ritual battle to two competing views of love (not the whole story, needless to say): for Martha, love’s essence is trust; for Lance, love’s essence is permission to be creative in all ways. In the heat of battle, such themes and the stories that contain them always seem irreconcilable. In fact, they can be reconciled, but the effort it takes to resolve them is great with couples, less so with coworkers.

The Relevance of Behavioral Profiles

Although structural dynamics Level IV (story) is where themes reside, Levels I through III are also useful in understanding how themes and situations become truly toxic. Consider impasses like these:

Note that these examples all involve communication between people with different behavioral profiles. All involve, as I put it in Chapter One, model clashes in cross-model conversation.

All of them also involve what I call negatively tainted attitudes toward difference. This is really the root of problems in high-stakes communication. Emotions twine themselves like spiked vines around a provocative word or phrase that someone utters “in the room.” From his own behavioral fortress, someone fires a shot. If the situation is pressured, someone else (some “other,” seeing and hearing things from a different behavioral profile) fires back from her own behavioral bastion. If the stakes are sufficiently high, an explosive point-counterpoint (move-oppose) sequence ensues. Friends, colleagues, and lovers who are “other”—formerly loved, liked, or tolerated—become enemies, targets of dislike, disdain, and contempt; and the room turns toxic.

Competing Themes and Their Shadows

As I suggested in Chapter Six, the story of imperfect love is the child’s first creative act, a personal story of disappointment in love and a story that quantifies the kind and extent of perceived damage. I’ll say more later about how the child reckons that perfect love will come in adulthood, in the joining of two heroic figures, the truant hero of the child story and a new, adult heroic self.

Experience tells most of us how difficult it is to achieve such an ideal, but that is no longer the problem. The problem henceforth is the “baggage” we carry forward along with our story—the things with which we encumber ourselves in various ways. To explore this, think of our limiting choices of language, how we express ourselves, our means of talking our way to life’s two essential goals: love and achievement. In a deeper metaphorical sense, the baggage is also our shadow, especially our dark side, which not only slows us down but actively trips us up.

Here is another way of describing our high-stakes themes: in our pursuit of love and achievement, we carry also a highly charged sensor for words and phrases that, in high-stakes situations, offend our sense of the ”right” and “wrong” way to be. Under the pressure of threatening events, individuals’ insistence on their own “rightness” also requires that those who are “different” (or “other” in the sense that they perceive the threat differently and use different language in search of solutions) must be “wrong” and therefore deserving of disapproval and, in the extreme, attack. This tendency to attack falls within the dark side of our behavioral repertoire, the home of our shadow.

Through their competing behavioral profiles, paired individuals bring into their relationships competing themes with explosive potential. That potential derives from the shadow baggage that their thematic stories invariably lug along.

FROM HIGH-STAKES BEHAVIORS TO SYSTEMS IN CRISIS

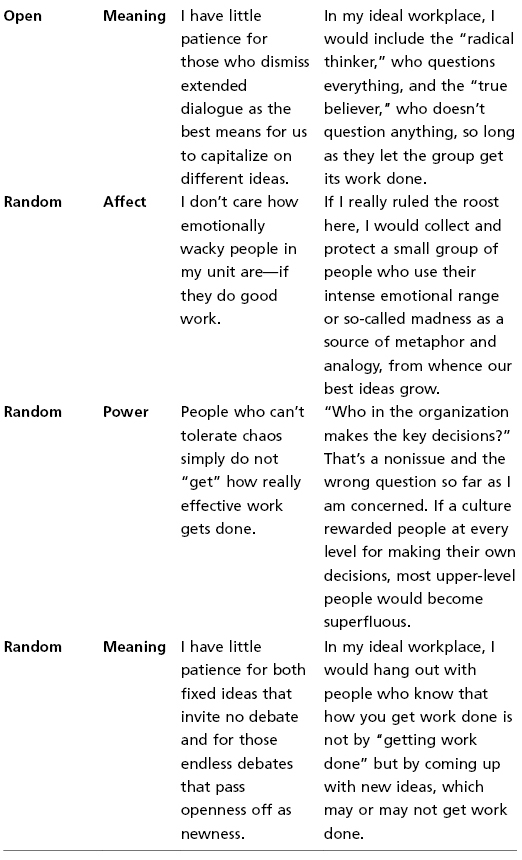

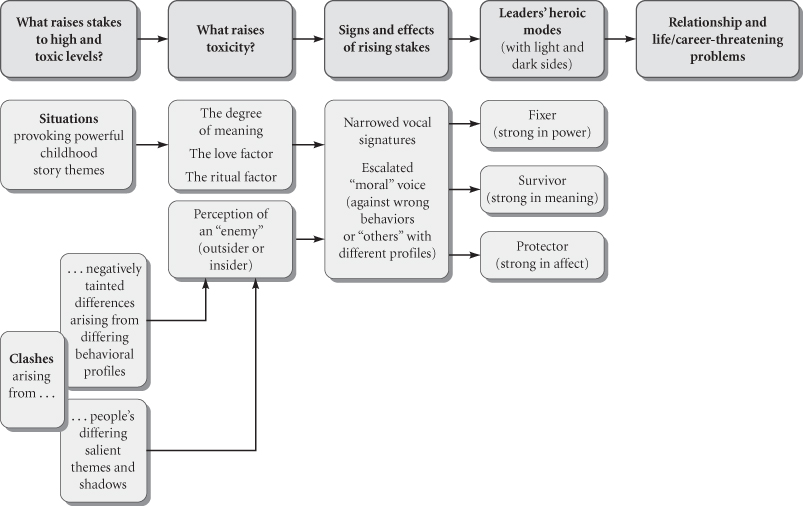

High-stakes behaviors put stress on couples, teams, and other interpersonal systems. The framework in Figure 8.1 shows such behaviors circling out of control.

Figure 8.1 A System in Crisis

The rest of this chapter and the next deal with the structural dynamics view of high-stakes and crisis behavior. Six phenomena are at work here:

Work on Ralph’s Awareness

The aforementioned framework of events underlies what we will see unfolding both at ClearFacts and in Ralph’s marriage.

By now Duncan was well into describing to Ralph structural dynamics perspectives on high-stakes themes, and Ralph was seeing components of the theory all over the place, including in the recent skirmish between Martha and Howard in which he became embroiled. In a meeting with Duncan, Ralph also reported a familiar skirmish he’d had with his wife, Sonia. “Only recently it has turned into a serious wrangle, no, almost an armed conflict the way we got firing away.”

Duncan teased out the toxic themes involved, suggesting that Sonia felt abandoned and so attacked Ralph when he worked into the night even after trips away that already exceeded her tolerance. Ralph would answer her saying, “My commitments are irrevocably who I am.” At that, Sonia would erupt with, “Your commitments!! I thought your first commitment was to me.” They were off and running.

Duncan advised him to wait until he saw the next eruption, preparing Ralph on how to intervene to nip the fight in the bud. Ralph was amazed at how well it worked. As he reported back later,

RALPH: As you suggested, all I did first was bystand, telling her I saw exactly what ticked her off. Then I made a follow action, telling her that what she’d pointed out in me was true, but it was also something I don’t like about me, either. Then I invited her to move. Well, she had a lot to say. I learned a lot I didn’t know about her history in relationships. Dunc, it can’t always be that easy, can it?

DUNCAN: It isn’t that easy, Ralph. You’re luckier than most. Sonia is more self-aware than most people, including you.

RALPH: So give me the theory that was based on.

DUNCAN: Sorry—you have a way to go before we turn to any theory or model of intervention. For now, just practice what you know until you are more functionally aware.

In Duncan’s model, the leader he coaches ideally achieves functional awareness (an understanding of how the structure and patterns of communications in all of his relationships play out in face-to-face relations) before developing his own leadership practice model. Without thorough awareness, the leader lacks adequate control over the key component of his practice model: the role of self in what he sees and how he acts on what he sees—be it “in the room,” in larger rooms, or on the world stage.

In high-stakes situations, self-knowledge about one’s low-stakes behavioral profile is still important but not sufficient. In high-stakes situations, a leader’s best efforts can be foiled and miserably fail him. He therefore must be aware of his shadow and take responsibility for it; know the role behavioral propensities play in his and others’ reactions in high-stakes situations; be able to grasp how different people with different profiles will react differently; and manage his team system and himself in that system even in the midst of crisis.

Learning to Listen to Voices

Uniquely, structural dynamics calls attention to a wide range of voices heard “in the room” that allow leaders and their coaches to recognize (diagnose) constructive and destructive communication structure.

Earlier in this chapter, I spoke of “seeing with one’s ears.” In Chapter Two, I noted that voice refers to the underlying manner, pitch, rhythm, tone, and other nuance speakers give to their words, and that voice can help us identify, for example, the speaker’s action stance. Leaders should pay sharp attention to the voicings of others for what they tell of those people’s meanings and intentions, and to their own voices for how those they intend to influence will hear them. Voice is subtle. It is also, as poet Jane Hirshfield says, “the underlying style of being that creates a poem’s rounding presence, making it continuous, idiosyncratic, and recognizable.”1

Is yours the voice of authenticity, of modest wisdom, of fertile curiosity? Or of disinterest, of skepticism, of elitism, or of bullying or disdain? At this point I would like to deepen your sense of voice with the concept of vocal signature. The structural dynamics model suggests essentially nine vocal signatures, each one deriving from the combination of one of the three basic operating systems and one of the three communication domains. So, for example, if you are functioning comfortably in an open system in affect, that preference strongly shapes the vocal signature you project.

In low-stakes situations, you may employ many different vocal signatures. In higher-pressure circumstances, however, your range of signatures narrows to conform with your basic behavioral profile. At high-stakes moments, your vocal signature also takes on the imprint of your shadow—the light and dark imprints of fear and desire that stem from your deepest stories. In short, in escalating, circularly caused miscommunications with “other(s),” your basic vocal-signature-plus-shadow takes over and becomes how you are heard.

“Get that report to me by the end of the day” is the unmistakable sound or vocal signature of closed power, even in low-stakes mode. But when you hear a closed-power person label a subordinate in public as “a complete incompetent,” the subordinate hears the theme of “being publicly humiliated” (one of the ten universal themes listed earlier) and feels the moral tone and anger of the closed-power speaker’s shadow.

Sender Voices, Receiver Reactions

Negative vocal signatures are likely to trigger anger in the person (“receiver”) hearing any one of them. The following list is not exhaustive but offers a sampling of themes a sender may express that are likely to trigger strong reactions in receivers.

Themes That Trigger Reactions

- Having to interact with one’s “fear opposite,” one’s nemesis

- Being degraded or humiliated when one can’t strike back

- Seeing someone being degraded or humiliated in public

- Being suppressed or restrained in the freedom to act

- Having one’s creativity stifled or squelched

- Being told one is a failure or incompetent

- Having to engage in pseudo-intimacy

- Living or working with someone who habitually lies or deliberately distorts the truth

- Witnessing violence, torture, or the rendering of physical harm

- Witnessing the unjust treatment of the powerless

- Witnessing cowardice or the fear of risk

- Betrayal of others for any personal gain

- Fear of loss of control

- Fear of chaos or anarchy

- Having one’s feelings dismissed or belittled

- Witnessing or experiencing loss of emotional control

- Fear of displeasing a loved “other” or valued authority figure

- Being subjected to the exercise of absolute authority

- Having one’s truths or ideas prohibited or revoked

- Being involved in or witnessing intense conflict with others

- Being called shallow or superficial

- Being with people who disguise ideology as ideas

- Being with people who are ambitious for financial gain only

- Being with people who evidence “eccentric,” “bizarre,” or “freaky” behavior

- Being with people who are inauthentic or phony, or who make false claims

- Being denied the right to be heard (feelings, ideas, solutions)

Watching Shadows

Structural dynamics seeks to separate itself from pathogenic explanations of behavior and to find a balanced view of the shadow’s contribution to behavior, particularly in high-stakes circumstances, which typically do trigger verbal shadow behavior in the form of disapproval, attacks, criticism, censure, denigration, or blame. Remember that all of us have light and dark sides. Even “saints,” stars, and cultural heroes, people whose light sides we exalt, have shadows, as do leaders and their consultants.

In my practice, I ask leaders to get to know and take responsibility for their own shadow and the impact their dark side may have on others. When they do so, their light side also emerges, flourishes, and is recognized. Only as the individual claims ownership and responsibility for his or her own behaviors can such change come about.

Escalation

In situations where the stakes are high for at least two players, escalations can occur in which someone “blows his top.” What makes him “dangerous” is his potential for verbal and, at times, potentially physical violence. As the escalation spirals upward, energy and volume are driven upward by more and more debasing, denouncing, and intimidating moral judgments. What begins as intolerance for difference ends in the language of disdain and contempt, often accompanied by threats and other violent actions: “You’re fired!” “I want a divorce!” “Get out of here before I … !”

Tops can blow in any context in which players are seriously invested in self, in other players, and in outcome; and, of course, these explosions are often triggered by themes transmitted by the “other.” Such escalations are most common in intimate relationships where love and identity are directly at stake, but anyone who has been party to what happens in the “back room” knows that politics and business are not exempt. The principal driver of this escalation is one’s moral voice. Its prevalence in high-stakes situations almost earns it the right to be called a fourth language territory in high-stakes settings: a “moral domain.”

Noise

An important attendant of escalation—its final phase, in a sense—is noise. By noise I mean the din that causes us no longer to hear the words of the “other.” What we hear, if anything, is the roar and screech of our own voice. An escalation may begin with an exchange like, “What you said caused me to react as I did.” “No, damn it, what you said caused it all!” But it ends in senseless threats of divorce or of being fired, or sometimes in physical violence between spouses or between parents and children. Or short of that, but no less tragic for communication, the noise level rises until someone cries uncle, or the resounding din itself silences all.

The most common “cause” of noise (cause is usually circular in origin, remember) is a mismatch in profiles, with their underlay of triggering themes and their shadows.

Mismatches in a Business Setting

One of the most famous business mismatches in recent times ended in the “corporate divorce” between Steve Jobs and John Sculley at Apple computer in the 1980s, which began as an idolizing business romance but escalated to demonization in just two years.2

Some mismatches—like closed power versus random power—are so fundamental that clashes will occur in just about any context. In the context of a college philosophy department, meaning will be central to discourse and to communication clashes. In the military, power is at the center of discourse. Central to discourse in the Vatican, a rather special religious setting, is meaning as power, with closed-system features. From among many, each institution chooses its own battlegrounds.

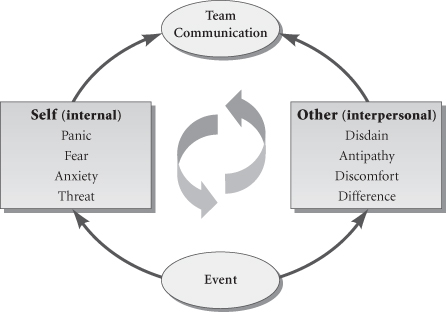

From among more numerous possible mismatches, I will elaborate here on three that apply at ClearFacts and that occur often in other business settings and in organizations that consult to them, as well as other institutions (educational, for example) seeking fiscal savvy and profit:

- Closed power versus random power

- Closed meaning versus open meaning

- Closed affect versus open affect

One reason that all three mismatches I have chosen involve the closed-system preference is that the closed system is the backbone of most large business organizations and occupies the core of preferred leader characteristics. A second reason is that a mismatch between a closed system and any other system type most dramatically and visibly highlights differences.

Figures 8.2, 8.3, and 8.4 show language that each mismatched stance and domain uses to trigger the other’s reactions, in escalating sequences. I focus here on words or phrases alone to encourage you to train your ear to listen for and recognize them in the room. Also note that in the heat of the moment, obscene, denigrating, and assaultive adjectives and nouns almost always accompany the triggering words.

Figure 8.2 Closed Power Versus Random Power

Figure 8.3 Closed Meaning Versus Open/Random Meaning

Figure 8.4 Closed Affect Versus Open Affect

Once sensitized to what triggers both one’s own self and the self of some “other,” our “hearing” becomes more acute. The very words people use are clues to their critical childhood stories and the typical preferred structures these stories have promoted: their behavioral profiles and propensities; how these sound in low stakes; and, most important, how they trigger reaction when the stakes are raised, at which point the sounds (voicings) are unmistakable.

ANOTHER DONNYBROOK BETWEEN MARTHA AND HOWARD

Martha had been suffering from insomnia and had entered a period of drinking too much at home after work. She wasn’t keeping up with her friends, a source of nurturance for her. She was angry at Ian; disappointed in Ralph, who had been on the road too much; and obsessed with Howard. Lance was relieved to be out of the line of fire. Wanting to make up for his faux pas, but knowing her touchiness at times like these, he tried to post himself at just the right distance, close enough to let her know he was “there,” but outside her “fussiness zone,” which he knows all too well. They squabbled, but he managed to keep the lid on.

In the meantime, Martha had her eye on Howard’s every movement, her ear on every word, her senses open to every mood. Whenever he mentioned TJ, she was on him. How Howard managed to keep his cool impressed her. She meant to make him squirm, but was failing.

Martha decided to turn to Ron. Over time they’d gotten close; in fact, in this period of personal strife, he had replaced her friends as a source of outside connection and nurturance (affect).

“I see what Ralph sees in you, Ron,” she told him. But it was reciprocal. Finding it easier to share his personal life with Martha than he expected, Ron let her elicit his childhood story and was grateful that she did.

“And I see what Ralph sees in you, Martha,” he said.

Then Martha opened up further: “Let me speak the truth, Ron. I have an ulterior motive. I want your help in getting the truth about what’s going on in Asia. When I was there I met your fiancée, Lani. She told me all she knew, but knows enough to mind her business. The whole atmosphere reeks of poison, worse than sulfuric acid. You won’t believe this, but when I got to the hotel after my visit, I threw out the clothes I’d been wearing—my best dress, damn them. I want Lani’s help.”

Ron surprised her. “I spoke with Lani after your visit, and I have her permission to tell you what she told me. Lani was among the women who sent the anonymous e-mail. At the time, sexual predation on Howard’s part was rampant. Since your visit, Howard and TJ have been behind closed doors a lot more than usual. Also, Howard’s added spikes to his iron fist. Both men and women feel and are acting like they’re in police state.”

Martha swore herself to keep from Howard what she now knew, until the appropriate time. But she couldn’t keep the lid on her hatred of the man. During a private meeting to exchange views on a new hire, a chance remark by Howard released her pent-up emotion. Howard, finally showing his darkest side on the home front, was anything but a pushover. Here is a sample of the words each used in their explosive point-counterpoint confrontation: outright liar–nosey sleuth; pleasure in causing pain–bleeding heart; ruthless ambition–emotional basket case; sexist con man–whiney bull-dyke; cruel prick–angry bitch. Both knew a large explosion was coming, but for now they escalated together until they both were worn down in noise and stony silence.

Figure 8.5 serves as an overview of the preceding discussion and hints at where Chapter Nine will take us.

Figure 8.5 Structural Dynamics and Rising Stakes

- What theme triggered your reaction?

- Can you track your reaction to a story from the past?

- What tone of “voice” got to you? Is this familiar?

- Is there a story here, too?

Take as much time as you need to reflect on what you believe others say about you.

- What do they say is your most horrendously objectionable behavior in high-stakes times?

- Specifically ask, “Do I invite and welcome critical feedback? How hard is it for you as a peer to tell ‘the truth’?”

In high-stakes situations, people’s behavioral profiles tend to detract, at times to breakdown, levels. Begin to pay attention to how internal dynamics influence high-stakes behavior. Chapter Nine will deal with external influences.

- Are you able to predict, on the basis of mismatching profiles, who will clash with whom when the stakes are raised?

- Are the dark sides of one or both players already in evidence?

- Can you identify the themes each is sensitive to and the stuck actions that spur escalations? Can you “sense” childhood stories in play?

- Try to predict and test your predictions. Did you see trouble looming before it happened?

- The next time trouble does arise, step in. A strong bystand that seeks to bridge differences is your best bet. But do not be dismayed if the problem reappears.3

Knowing how to step into a volatile field with a precise action to defuse escalating sequences is integral to communicative competency, but to do this you must first learn to read the room with diagnostic and structural accuracy.

Everything said about leaders and high-stakes behavior applies to you, too, as it does to everyone else. But there is one additional high-stakes issue special to you as a coach: occasionally having to tell uninvited truths to a leader who has the power to ignore or fire you.

- How comfortable are you with power in general?

- Do certain profiles threaten you or put you off?

- What about leaders who have unacknowledged shadows?

- What do your own profile and formative stories have to do with these effects?

- Does your model include technical guidelines for dealing with resistance of various forms and intensities?

- Have you ever knowingly compromised your model and its principles in the name of expediency? Out of fear?

- Would you be willing to rewrite the compromising scenario in order to design a more desirable outcome?

Notes

1. Hirshfield, J. Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry. New York: Harper Perennial, 1998, p. 29.

2. See Diana Smith’s Divide or Conquer: How Great Teams Turn Conflict into Strength. New York: Penguin, 2008.

3. Many problems in teams are so entrenched that it takes a multistep intervention to effect change. To address this issue, a book by the author tentatively called Making Change Happen is in progress, which is a detailed description of the structural dynamics practice model. Making Change Happen relies on Reading the Room for its theory of the thing, a concept described in Chapter Twelve of this book.