chapter FOUR

Level III: Systems in Control of Speech

Ultimate conversational power rests not in individuals but in the systems they create and deploy to control speech behavior. This is Level III of the structural dynamics model in Figure 1.1. (For “system” you might also think loosely of the phrases “governance pattern” or “authority paradigm.”) This level is the third and last we will need to create a behavioral profile.

Please remember that in continuing to focus on speech behavior, we neither ignore nor downgrade the importance of physical action and nonverbal behavior. We focus on speech behavior because that helps us lay out the theory of face-to-face communication as simply as possible.

Even if their formal learning about systems is minimal, most potentially effective leaders have a good intuitive sense of what makes people and organizations tick. They tend naturally to think systemically. Organizations often don’t look for this quality, however, and instead choose leaders for their ability to get others to follow, for the results they get, and for other legitimate qualities (smarts, courage, power, expertise).

RALPH’S BOMB

During the evening following his meeting with Ron Stuart, CEO Ralph Waterman typed an e-mail to his team about him. Until that point, the team knew about Ron only as a fast-rising star in ClearFacts’s Chicago office. He’d been picked up a year ago from a start-up. Beyond that, Ralph had told them Ron was of “tough mind and big heart, which he does not wear on his sleeve,” and that he had an “unswerving” commitment to green energy.

Important announcement! My meeting with Ron Stuart this afternoon has exuberant possibilities for growth in a sector in which ClearFacts has, or should have, considerable interest—renewable energy. Ron has a lead on another start-up that is ready to be bought. More details at our Monday meeting.

To that he added in closing:

We’ll leave for a later time Ron’s outrageous ambition as expressed in the demands he is making. On Monday, let’s just consider his case, while putting his demands on hold.

Then, on second thought, Ralph deleted those last lines.

Monday arrived, and the mood of the small talk before Ralph arrived (you could always count on his being late) was shamelessly celebratory. Howard Green had been boasting for weeks about what a good start he had gotten the Asia sales office off to, and continued while glossing lightly over the anonymous e-mail. Ralph had been right: Asia was years ahead in new green energy technology and was an untapped market for investment.

Ian Maxwell’s news from operations was that the house had been swept clean of “dead wood,” cutting costs; and company stock was soaring following its Floridian acquisition. But after fifteen minutes, a frustration set in that Howard was first to openly state: “I’ve a plane to catch; where in hell is he? I only delayed my flight because Ralph’s e-mail said he had an important announcement to make.”

Martha Curtis sighed out a reminder, “He really can’t tell time. And refuses to wear a watch.”

By the time Ralph showed up, the mood was foul. He’d intended to hold back about Ron Stuart’s demands until he’d had time to measure the team’s reaction to the initial e-mail. But he’d barely opened his mouth when Howard, although typically able to censor anything less than deferential to his bosses (Ralph and Ian), unleashed his fears unchecked: “What does that slithering, reptilian backstabbing SOB really want?”

Unnerved, Ralph plunged in: “He wants a salary based on merit past and future and a promotion that includes his joining this team and reporting to me. I didn’t say no.”

As if on cue, Howard’s elbow knocked a thick file onto the floor, scattering its contents underfoot. Howard swore, and they all started talking at once, basically siding with Howard.

MARTHA: With guys like Stuart, that “no” means “yes.”

IAN: Being CEO, Ralph, doesn’t license you to break the rules.

HOWARD: Ralph, I can’t help saying this. You don’t know that one of Ron Stuart’s closest buddies in Chicago’s marketing office is probably after my job? And here you are …

ART: (No actual glance at Howard, but a look that says, Good riddance!)

MARTHA: A rank betrayal, boss. I thought we all were guaranteed a voice in all major decisions.

IAN: The “rules,” Mr. Waterman, rules. All top-level promotions start with operations—me. However they make their way to the team, they stop at my desk. My desk. Not in that chaotic heap on … well.

RALPH: (Clenching his teeth, controlled but clearly angry) Maxwell, you know nothing about what’s being seeded in my “heap.” Keep your rules. Keep your order. But keep your butt out of my life!

Before reading on, try to identify Levels I and II in each line of dialogue here. Do the same for the next exchange.

NOT JUST A BAD MEETING: A SYSTEM OUT OF CONTROL

For hours after the meeting, Ralph had no real idea what had gone so wrong. Later that day, he debriefed about it with Duncan.

DUNCAN: Well, you certainly stirred things up.

RALPH: (Mumbling) Yeah, I must have miscalculated. I hadn’t expected such a violent reaction. Obviously I did something stupid.

DUNCAN: Not “stupid.” Random.

RALPH: I don’t know why, but I always felt a little, well, flattered when you’ve used that word on me before. Now it sounds a little dirty.

DUNCAN: No, no. I just mean to point out your random propensity. Not saying it’s good or bad, but it’s a pretty strong part of your profile. It has its upside, mainly creativity.

RALPH: And the downside?

DUNCAN: Chaos.

RALPH: Guess I dropped a bomb.

DUNCAN: Right. And not your first. But more than that, your system’s bombing.

RALPH: My “system”? I’m imposing a system? By being “random”?

DUNCAN: Right. Oddly enough, random is a kind of system …

LEVEL III: OPERATING SYSTEMS

Concerned with human social systems—particularly with communication and information transfer—structural dynamics takes a “systems approach” to face-to-face relations. At Level III, operating systems, it looks at systems or norms of communication that persist both within and surrounding the individual and that shape her interactions in the room.

Systems Approaches in General

A systems approach is a great asset to any coach or leader. Such an approach to any subject views all entities (from microscopic cells to the vast cosmos) as whole systems whose parts are dynamically interdependent. Systems thinking has changed and continues to change our grasp of how the world works, taking us from simple paradigms to highly complex models in such disciplines as biology, economics, engineering, and so on. It has also touched most fields of application, including psychology.1

The following concepts are central to systems thinking:

- The role of circular causal reasoning. As noted in Chapter One, disquieting events are often regulated by circular causal reasoning in which, say, Person A influences Person B, and B influences A; they anticipate each other in ways that “prove” that their expectations are correct. The understanding of most relationship dynamics is more suited to systems logic than simple cause-and-effect linear thinking. For example, in the escalation between Ralph and his team, Ian did not “cause” Ralph’s angry response, and Ralph’s e-mail did not “cause” Ian’s rage. Their encounter was structured by a system already in place between and around them, albeit quiescent up until then.

- Positive feedback loops that increase or amplify a particular output. For example, before Ralph entered the room, the angry team reinforced each other’s feelings. Positive feedback can be deliberately used to accelerate change, transformation, growth, or evolution in a system. But excessive use of positive feedback can send a system into runaway.

- Negative feedback loops that reduce output. Ian’s insistence on making sure that all paperwork goes through him for approval is an example of a negative feedback loop. It is Ian’s attempt to control Ralph’s behavior. Negative feedback can be used to increase the stability and accuracy of a system, but excessive negative feedback can run down and stifle the system.

- Control devices in feedback loops.2 One simple feedback device for controlling conversations is a meeting’s agenda, which allows certain information into the conversation while screening out other information. In very complex systems (societies, financial markets, large business organizations), it is not always clear what the feedback loops and their controllers are, nor is it easy to know what to do about them when they get out of balance.3 Moreover, multiple controllers may exist with multiple feedback loops operating at various levels of the organization. These elements operate with varying degrees of autonomy, can compete with one another, and are often changed by that competition.

Operating Systems: Open, Closed, or Random

In structural dynamics, an operating system is the implicit set of rules for how individuals govern boundaries, behavior, and relationships in groups. The operating system’s role is to control speech—to enable, discourage, and monitor the types of speech acts that arise in a group conversation.

Growing up and living in such systems as families, classrooms, youth teams, and other organizations, individuals develop personal preferences for certain operating systems and manifest those preferences both in their own behavioral propensities (how they speak) and in the systems they choose to join or foster around themselves. Structural dynamics studies an individual’s speech patterns for clues to his or her preferred operating system types, and studies a group for clues to how it is working, whether the group’s system type is easily recognizable and shared, or whether, internally, the group may be conflicted with a mix of preferences and system types.

Our Level III model differentiates three operating systems—three alternative patterns of rules and expectations for how people should behave: open, closed, and random systems. None is inherently better or worse than the others; each has its value and limitations. As I will demonstrate using ClearFacts, we can tell whether a given system is open, closed, or random by looking into the following:

There is some overlap of features among open, closed, and random systems, and having a preference for a certain system does not mean that the individual promotes that system in all circumstances. For example, a leader who leans toward open systems may decide to take a more closed approach at times.

Recognizing Preferences for Systems

Organizations, teams, and individuals have preferences for one or another of these systems of control. Individuals know well the preference of the system in which they find themselves. That it may differ from his or her preference is a serious matter for individuals and for systems as well. In the following dialogue, watch for these preferences of the team members at ClearFacts:

- Art and Martha’s general preference for open systems

- Ian and Howard’s general preference for closed systems

- Ralph’s preference for random systems

In describing an operating system, it is useful to make some judgment about how well the system is functioning with regard to its presumed social purpose. And as individuals begin to recognize the various control mechanisms that dominate the different types of human systems of which they are a part, they can begin to learn when and how to shift the rules to fit the situation at hand. In other words, a skillful, influential member of a group may be able to temper and complement one system with another, depending on the occasion.

THE OPEN OPERATING SYSTEM

The best environment for me is one in which every individual voice can be heard in the interest of designing and meeting the group’s goals.

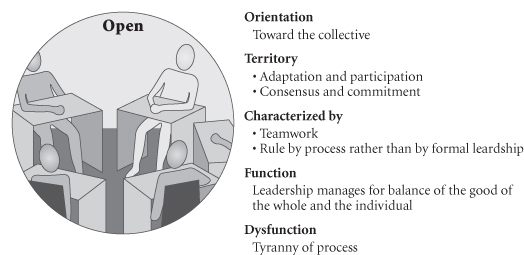

Figure 4.1 outlines the open operating system. The following might be obvious indicators of a family operating under an open system: authority for decisions is shared and not held solely by the parent(s); children are free to verbally challenge the limits and decisions made by the parents, though the parents have ultimate authority when consensus can’t be reached; outsiders or newcomers are invited in to special family gatherings or decisions frequently and without fanfare (also found in a random system); controversial topics can be discussed at the dinner table even if the opinions expressed are in conflict with those of the parents.

Figure 4.1 The Open Operating System

Characteristics of Open Systems

Open systems require communication. Work gets done by openly deliberating and exploring each individual’s needs. In fact, in an open system, the needs of the individual are initially placed before the needs of the organization, with the assumption that by respecting all individuals and the challenges they face, the organization can develop shared responsibility, purpose, and leadership. Although it begins with focusing on individuals, the open system ultimately seeks a collective decision arrived at by consensus. Community grows out of deliberate respect for the individual, compromise, and reaching group goals.

Orientation

Because open systems lean toward balancing the good of the whole with the good of the individual, they are the darling of behavioral consultants, therapists, and similar practitioners. Organizational systems, too, advertise themselves as open. But what practitioners and organizations espouse may differ sharply from what they do. Often practitioners with strong open-system rhetoric retain a firm, closed-system underside that subverts open values. The result can be a cynical perception by employees that this “program of the month” shall pass like all the other new ideas proposed by management before they take root.

Values

The open operating system depends on people’s valuing the process of learning and adaptation through participation. An individual’s “right to be heard” is sacrosanct, but teamwork and discussion should ideally result in consensus decisions.

Boundaries

Typically, it is very easy to recognize an open system’s permeable boundaries, where external inputs are accepted and often welcomed. A group operating as an open system or individuals with this propensity may invite newcomers and new ideas into their space in order to adapt and grow.

Access to Information and People

Because its boundaries are permeable, an open system’s personalities often become known as the information sharers in the larger organization. They distribute FYI memos and reports, their office doors may always be “open,” and they may walk in on others or blithely invite themselves to meetings.

Limits on Speech

No one person’s views are assumed to be better than anyone else’s, so challenges and new ideas are welcomed. Dissenting or contradicting voices are tolerated. At the same time, most open systems in organizations also have developed guidelines and procedures borrowed from closed systems for ending debate and ensuring that the group acts expeditiously.

Feedback Mechanisms

In the open system, there is balance between positive and negative feedback loops. At the individual level, positive loops predominate and serve to increase or amplify new behaviors. To reach consensus, the group and the nominal leader, who is responsible for keeping its rules, are empowered to step in with negative loops to end discourse.

At ClearFacts, Art has a strong propensity for the open system, using it to generate new ideas and solve problems in a thorough manner. During one of his marketing team meetings, after an unexpected development suddenly threatened their current project’s outcome, his team went on for hours seeking solutions from all angles. In that open-system discussion, the expression of new information was invited, creating a positive feedback loop that amplified this behavior.

When he judged that the group’s “positive loop” discussion had run dry, Art said, “We haven’t heard a new idea in the last hour. It’s time to vote on what you’ve agreed are the two best approaches.” As leader, Art now wanted closure for the discussion. The open system had reaped its benefits, and it was time to move on.

But he was loudly interrupted by one of his people—a strong mover in meaning: “I’m not done yet. I have a new angle on an idea I shared earlier.” The other teammates groaned, signaling Art to pursue closure, which, with gentle insistence, he did. Without further discussion, a vote was taken and the meeting adjourned. Art’s use of a negative feedback loop had diminished the creative behavior and allowed the group to move to consensus.

Ways of Managing Deviation

At some point, every system will experience deviation: one or more individuals will violate its tacit rules. Deviation may come from the group’s experience of carrying a good thing too far (say, the open-system discussion that goes on too long)—what we refer to as “tyranny of process.” Even more common is deviation created by someone with strong propensities for a different system, for which he advocates at that moment. Such behaviors constitute a model clash with the currently operating system.

When a person preferring closed systems finds herself in an open one such as Art’s creative session, she is likely to show impatience and ask for premature closure. The individual may demean other members who follow the group’s open-system preference, may become even more confrontational, or may shut down entirely.

When a random-tendency person finds himself in an open system, he may seek to disrupt smooth conversation with the intention of finding more creative solutions. He may not only insist on sustaining someone else’s right to talk but also challenge the group’s titular leader from moving the group to premature closure.

Function Versus Dysfunction

In theory, if not in reality, a deliberative body like the U.S. Senate is an open system: it seeks to resolve differences through a process of open exchange. Often in dysfunctional open systems, process rules are supreme and pervasive, and individuals use them to avoid resolution and action. Closure is rare, and each individual is allowed full expression at all times, often limiting the collective ability to take quick action or meet critical deadlines. Thus, ironically, the total acceptance of all input to the process can also lead to the organization’s demise, when individuals intent on destroying it have equal access to decision making and governance.

Open-System Preferences at ClearFacts

As I noted earlier, Art prefers an open system during some phases of leading his own team. Martha displays a strong, broader open-system preference. Martha’s model clash with Ian in the leadership training program (illustrated in Chapter Three) was about both their language preferences (Martha for affect and Ian for power) and their system preferences (Martha for open and Ian for closed). Earlier in this chapter, we saw Martha admonish Ralph for violating the open-system rules he’d promised the team. Also in that heated interchange, Ian (“the ‘rules,’ Mr. Waterman, the rules”) invoked his closed-system preference, and imposed it not only on Ralph’s breaking his pledge but for doing so in a random way.

THE CLOSED OPERATING SYSTEM

I want to live in a world that is traditional, stable, orderly, and predictable.

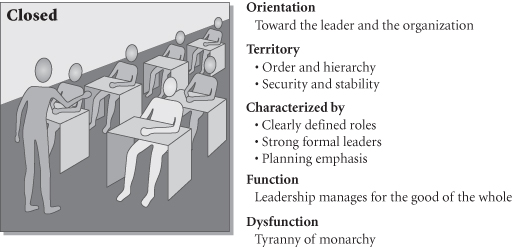

Figure 4.2 briefly summarizes the closed operating system.

Figure 4.2 The Closed Operating System

Characteristics of Closed Systems

The closed system is ultimately the backbone of most organizations. It is the most efficient means for getting work done. (Open systems do as well, but take longer, and the random system, though arguably inefficient, is the system of choice when creativity, rather than efficiency, is called for.)

Orientation

In open systems, leadership can be shared or diffuse, but in closed systems, strong, formal leadership is essential. Closed-system leaders typically have clearly defined roles and formal authority via job titles, rank, or seniority. It is their notion of needs that the closed system serves.

A closed system regulates the life of its members, particularly the time and space within which people work or live. For example, tracking individuals’ time and activities during the workday, monitoring inclusion and exclusion at meetings and conferences, and strict adherence to corporate policy suggest that a closed operating system prevails.

Values

Closed systems value tradition, and place community and history over the needs of the individual. This leads to strong calls for loyalty and self-sacrifice for the group. Adherence to procedures and policies that facilitate day-to-day decision making in the organization is expected. In exchange for this adherence, the governed get stability, security, and predictability.

Boundaries

A closed system survives by creating a boundary around its members, for their safety and protection as well as to enhance group productivity. At the boundary, intruders or dissidents are screened before entering. Physically, people with closed-system propensities appreciate the need for closed meetings and closed doors. Metaphorically, they consciously or unconsciously create a circle identifying who is in and who is out.

Access to Information and People

With active screening boundaries and clear understandings regarding speech, the closed system carefully regards who receives what information and who needs to be involved in various doings. It is important to note that well-managed closed systems are capable of excellent communication and group participation; these activities are planned and executed carefully for the organization’s benefit, within the leader’s control.

Limits on Speech

Given the focus on inclusion and exclusion, on authority and hierarchy, in this type of system, it is important to be aware of protocols, traditions, and rules (spoken and unspoken) regarding who can speak and when, and what they are allowed to say.

Feedback Mechanisms

In closed systems, negative feedback loops predominate, producing homeostatic mechanisms that maintain stability and moderate change. Negative loops keep the system stable through close regulation and control. When change happens by intention, it is done gradually. When change is happening spontaneously, the closed system uses negative loops to moderate change, disabling threats to basic stability.

Ways of Managing Deviation

The closed system uses negative feedback to diminish behaviors deemed unacceptable.

The open-system individual living in a closed system typically insists on being heard and may challenge authority and group norms to do so. The open-system dissenter usually also understands and respects the need for the leader to shut down new inputs, and so will typically not escalate a challenge into full rebellion.

Random-system individuals not only challenge the authority of closed-system leaders but often will attempt to undermine it. Punishment of one kind or another is expected within the closed system when randoms carry challenges to the point of anarchy and chaos.

Function Versus Dysfunction

In families, closed systems display strong authority by one or both parents, higher degrees of scheduled organization, and clear and consistent rules and norms for all to follow. Parents who “run a tight ship” feel strongly about what their children should be exposed to and protected from, and believe that discipline and responsibility will help the family endure tough times.

Well-functioning closed systems are stable and highly structured. Their leaders manage for the good of the organization, and depend on their own vision and skills to continue to be responsive and effective. In high-achieving closed systems, leaders know how to delegate power in its best form, by handing over both accountability and authority for certain functions and decisions to qualified others in the organization.

Prior to divestiture in the 1980s, the corporate culture of Bell System phone company functioned very well as a closed system. As a monopoly in the market, the various corporations in the system managed customers, employees, and shareholders with a high degree of central authority and consistency. Policies, rules, training programs, and processes were highly valued and consistently maintained. Because the company was driven by strong values such as customer service, employee retention, and employee development, most constituents valued the security and stability that the phone companies provided.

When a closed system predominates for too long, performance may become mindlessly robotic. Although the search for maximal productivity through repetitive and efficient processing achieves outstanding results at first, over the long term, these results break down. A system committed to authority and ritual also becomes less receptive to new information, innovation, and change. In today’s complex world driven by international and market demands, organizations that operate solely as closed systems are doomed because their workforce eventually loses its creative edge, their products imitate themselves, and competitors pass them by.

At its worst, the closed system has leaders who manage for their own benefit rather than for individuals and teams in the company. The organization experiences “tyranny of the monarch.” Many closed-system leaders strongly believe in the “rightness” of their vision, and their only means of protecting that vision is to seal themselves off from a world filled with contradictory and radical beliefs. Over time, those in charge develop unchallengeable control, and the learning and growth capabilities of the organization become severely disabled.

Examples of such systems that have become corrupt or harmful to their members are easy to cite and remember, primarily because the nature of the dysfunction eventually results in dramatic change to the system. Revolution, internal fighting, and the exit of key individuals are signs that systemic clashes exist and that a closed system is involved.

Although closed-system families can be high-functioning and nurturing environments for all of their members, perturbation frequently occurs when children reach adolescence. For some teens, rebellion is a natural stage of development.

When a closed system is threatened, leaders tend to increase the number of negative feedback loops and tighten up more with increased rules and punishments. The result can be tragic for individuals seeking to connect with their own different needs and identity. Feeling that they have no power to influence the system and that the system is a source of repression, they can spiral into depression or even despair. The best strategy for a closed system when faced with this kind of predictable challenge is to borrow from another system type as it maneuvers through this stage, finding ways to provide freedoms and the ability to voice opposition. Random and open systems could take the same advice. Both random and open systems at times do well to tighten their rules by borrowing from those of the closed system.

Closed-System Preferences at ClearFacts

In the dialogue in the section “Ralph’s Bomb” (“The ‘rules,’ Mr. Waterman, rules”) and in Ian’s statement to Martha, “When was the last time you calculated the costs incurred when a company coddles its workforce?” we can see evidence of Ian’s assumption that all systems should always operate as closed. This assumption causes him to miss much of what is going on and to be frequently misunderstood and undervalued by people committed to open and random systems. At home, Ian adopted and modeled his father’s closed-system tactics. Ian’s son, however, fought the closed system every step of the way as he strove to assert his own random-system preference.

Howard also prefers a closed system. He is insistently “top down” deferential to a fault with his bosses Ian and Ralph; and, as we shall see, in Asia where he is in charge, he controls with an iron fist.

Martha’s strong open-system preference could be enhanced by more closed-system tactics. In the dominantly open-system HR team she leads, Martha doesn’t actually “coddle” (as Ian might allege), but she does let her staff lapse often enough into a “tyranny of process” mode. On such issues as pink slips, they can and do go on and on. In the leadership training program Martha leads with Ian, her unflagging support for trainees does almost fanatically favor the underdog.

THE RANDOM OPERATING SYSTEM

I prefer an unpredictable, inspirational, and improvisational world where others respect my creativity and autonomy.

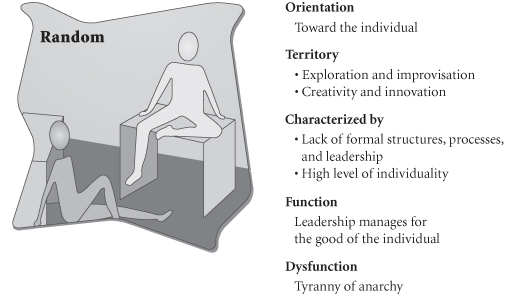

The random operating system is the rarest in established organizations today. It is also the least understood and most feared because it is rare and because it basically threatens to undermine the rule of certainty and control. Figure 4.3 illustrates it in brief.

Figure 4.3 The Random Operating System

Be careful not to conflate an individual’s random-system preferences—which can be creative—with research into possibly genetically “right-brained” or “left-brained” people. Structural dynamics posits that randoms are that way as a result of choices stemming from their early experiences. We’ll see this later on with Ralph.

Characteristics of Random Systems

Creative individuals who, rather than following traditional rules, make new ones, flourish in random systems. Start-ups are famous for creating something new and different, and random individuals are frequently the force that drives them.

Orientation

Random systems focus so strongly on the unique preferences of each individual that they are often viewed by outsiders as chaotic or out of control. Instead of lacking order, the random system represents a special kind of order of infinite possibilities.

It is not uncommon for individuals who prefer random systems to live their entire lives outside traditional organizational systems. During his most creative years, Picasso was surrounded by circle after circle of the newest and most creative minds. He pursued a multitude of diverse interests, from an untethered life of sexual expression to painting that mirrored his erratic and deep emotions.

Values

In random systems, individual autonomy and freedom are valued above all other organizational constraints or goals.

Boundaries and Access to Information and People

“Unfiltered” is the operative word for randoms: people as well as information are free to come in or travel out at any time. Day-to-day life unfolds with minimal constraint and formality. There are few standard procedures and structures; people are encouraged to “make it up” every time they tackle an issue. Naturally, randoms gravitate to innovative start-ups. They imagine new products that engineers (often closed-system types) make happen.

Limits on Speech

Random-system decisions can be made in numerous, very different ways; the process is based on ideas, not on status or structure. Input and leadership can come from anyone at any time, often from one or two individuals who happen to be dealing with the problem at hand. Who these individuals are is always subject to change.

Feedback Mechanisms

The rule in the random system is that individuals are not constrained but allowed to do as they will, moving, one hopes, toward some common goal articulated by the group. Positive loops predominate; negative loops (whose purpose is to close down change and bring about more stability) are rare.

Ways of Managing Deviation

Random-system individuals can find comfort in chaos. “Deviation” may be defined as “what gets in the way of a eureka moment.” Yet when chaos is introduced for its own sake, without regard to its effects on others, a line is crossed. When rebellion becomes mandated and becomes the cultural norm, it has the power to undermine institutions and has a strong destructive influence.

Closed and open types trying to express themselves in a random-dominated system may feel inferior, uncreative, and undervalued, and may be driven out or shut down entirely.

Well-functioning random systems rely on intuition, the same mechanism used to create and innovate, to know when to manage down or end discourse.

Function Versus Dysfunction

Because of its high degree of freedom and personal expression, an excellent random operating system can innovate rapidly. Its lack of restraint and its freewheeling style stimulate innovative thinking and products. Many R&D organizations and academic institutions were founded by groups of individuals who were firm believers in the creative potential of life in a random system. Random individuals in start-ups often invent not only their own unique ideas and products but also their own style of working. The subculture that Steve Jobs—a quintessential random—was fledging at the start of Apple was responsible for some of the most significant innovations of the twentieth century.

Unfortunately, as a random system grows and begins to require maintenance and sustaining features, its leader must turn to negative loops and other operating systems’ tactics. Earlier I cited Bell System as a high-functioning closed system; interestingly, during the same era, Bell Labs created a kind of “safe house” for a small group of unregulated randoms charged with developing innovations. In short, Bell maintained functionality by creating a small random system within its walls. In the 1960s, other organizations borrowed this practice.

At its worst, the random operating system provokes such rapid changes in direction and focus that no one has a clear sense of direction. People become confused and disoriented, experiencing the “tyranny of chaos.”

RALPH’S RANDOM-SYSTEM PREFERENCE AT CLEARFACTS

As Duncan suggested, CEO Ralph, a random, prefers and has tried to maintain an open-system paradigm for his management team. The following portions of dialogue from Ralph’s debriefing with Duncan convey Ralph’s sometimes unconscious random-system gestures and how other open-system and closed-system members of his team can react to them. Duncan and Ralph have already talked about what’s good about a random system and are looking at its darker side. Note that in this angrier realm, a random act by Ralph can also be arbitrary, autocratic, and effectively closed. I have witnessed leaders like this, who say, “Anything goes … Anything goes … Okay, you’re fired!”

DUNCAN: Whether it was conscious or unconscious doesn’t matter. You created chaos in that room. You dropped one bomb when you sent that e-mail announcing your dealings with Stuart. Chaos ensued at the meeting, and then you dropped another.

RALPH: I knew before I even mentioned them that Stuart’s “demands” would set them off.

DUNCAN: And then something further happened. Something happened in the room that lit a fuse in you, and you exploded.

RALPH: You mean when I lost it with Howard?

DUNCAN: You’re forgetting. The one you lost it with was Ian.

RALPH: That’s strange. Why don’t I remember it that way? Help me understand. What got Ian so ticked off?

DUNCAN: First off, you came late as usual. Many randoms can’t tell time, and that irritates and insults some people—like Ian.

RALPH: Me, I think of it as an endowment. I’m no slave to the clock like him.

DUNCAN: Nor concerned about demoralizing those who do live by the clock?

RALPH: For me, open-ended time-space stimulates and sparks ideas.

DUNCAN: You are proving yourself a random and throwing me off the scent, and you know it. You asked for help. “Help me understand,” you said. Remember? Look, Ralph, that RED you planted—sorry, that Random Explosive Device—you planted it there without warning, and it blew the system apart. Until then, the team you crafted worked fairly well because of a good spread of system types.

RALPH: Open, closed, and outright random me.

DUNCAN: Dealing with a pure, flawlessly true-to-type closed: Ian. Howard is less pure of a closed, if only because he is less mature.

RALPH: Martha and Art are both opens?

DUNCAN: Yes, and have flourished under your leadership. Randoms reward individuality, not obedience. That’s how you’ve steered them through their clashes—clashes in speech behavior, clashes in language preference, and now, with you caught up in it, their clashes in system types. …

Let’s look at the meeting again from scratch. What was the pivotal moment, when everything seemed to break down … who did what? Especially, what did you do to worsen the breakdown?

RALPH: I knew when I walked in that something was coming. The room reeked of anger. Funny, I don’t usually have that much trouble with anger.

DUNCAN: So what set you off?

RALPH: Bang. Howard’s voice. Gotcha. So I shot back.

DUNCAN: With what?

RALPH: What I said was … , I hadn’t said no to Ron’s demands, but I said it in a way that meant yes. Which Martha nailed in a flash. They got it, and boy, then, did they give it to me!

DUNCAN: Follow me in this, Ralph, but don’t dwell on it. Like all humans you have a dark side. What you showed them was the dark side of the random—the impulsive, chaotic, anarchic rule breaker.

RALPH: Ha! Sonia says that!

DUNCAN: And what happened next?

RALPH: Mayhem.

DUNCAN: Tell me in slow motion. The highlights. Start with Martha.

RALPH: Right. Well, like I said, Martha nails me on the not saying no that means yes to a guy like Ron. She also said I was leaving her out on the decisions. And how she thought I’d brought her here to build a participatory, consensual team.

DUNCAN: Which is exactly what an open-system type would say.

RALPH: Howard almost seemed unnerved by the whole thing …

DUNCAN: Scared. He sees himself on a steady climb to stardom. Howard’s a strong closed-system person who values predictability and the religious maintenance of order and due process. When order breaks down, he feels derailed and gets upset. What you did with Ron Stuart was a blatant sign of disorder and a threat to Howard’s life plan. And Art?

RALPH: Art? I really have no idea what his reaction was.

DUNCAN: Because Art is your best bystander: open in affect and power, but random in meaning. You’ve used his marketer’s image-making genius outside your meetings, but not his bystanding in the room.

RALPH: Art and I have never, not ever, clashed.

DUNCAN: That, I suspect, is because you are no different from the friends he hangs out with: artists, writers, poets, people who thrive on finding order in chaos. (Probing) So what about Ian?

RALPH: I lost it. Let’s face it, Dunc: I lost it.

DUNCAN: (Waits)

RALPH: But I’m not ready to talk about it just yet.

Story Roots of Ralph’s System Preference

Later, Ralph was sitting alone in his office when his thoughts went back to a memory that had triggered sudden anger in him in a previous discussion with Duncan.

His father’s face loomed inches away. “Look at your desk! Now look at my desk. Order, son, not filthy mess.”

“Your f—ing desk?” Ralph replied aloud. “Your desk is a graveyard: fresh-cut, two-inch grass on top, death underneath. My desk is a garden of exotic flowers the likes of which you can’t even imagine.”

Ralph’s father was a retired minister, aging poorly—a bitter old man who had missed his opportunity to bring something important to the world. He read, walked, and demanded constant small attendances from Ralph’s accommodating, uncomplaining mother. Growing up, Ralph dutifully loved but never respected his mother except in one respect that, even today, brought a smile to his face. Quietly enslaved, she secretly drank while playing out each day as the reverend’s obedient, respectful spouse. Curiously, Ralph, also secretly, approved of this as a private act of rebellion.

Ralph’s own rebelliousness—neither secret nor quiet—was one of their connections. He raised hell (with her nod of support) at every one of the six or more schools he attended between ages six and sixteen. At each, he established himself as king with his peers and court jester with authorities. When they depicted his playful infractions “as serious lapses in moral conduct,” he invited his elders to join him in a level of moral discourse beyond his years. The usual result was that what he received from those required to judge him were smiles, and, as he got from his mother, nods of approbation instead of punishment.

Ralph had two answers to the question, “Why so many schools?” which the school officials asked at each new school where his mother placed him. The first was obvious. Ralph’s reverend father was so difficult that it rarely took more than six months to a year for a congregation to turn out to be “incapable of making the changes I insisted on” and to ask him to leave. Ralph’s second reason came from other sources—the looks on the faces of kids, children of families in his father’s parish, as they left the reverend’s study in the far reaches of the house, ostensibly there for private religious counsel.

When Ralph could imagine such a thing and give a name to it, he accused his father—not in words, but with looks informed and reinforced by those he saw on the faces of the child visitors, both boys and girls, when they left his father’s sanctuary—of serial child molestation, an accusation that emboldened Ralph even more in the battle of words the two began to have.

How the Debriefing Ended

We can see the team meeting of this chapter as a sign of a suddenly destabilized system. What characterized the system before its slip into this state? It was a team whose leader very rarely interfered with its members’ freedom to “be who they were.” Ralph rarely asked for obedience. Any member could confront him as freely as they did one another. Order came not from Ralph, who cared little about it, but from Ian’s presence. Ian knew better than Ralph that he was balancing Ralph’s tendencies to let things go hither and yon. Ian also knew that he would never get credit for the sense of order he provided.

Ralph’s debriefing with Duncan ended on this note:

DUNCAN: Ralph, do you think you should have handled the whole thing differently?

RALPH: Yes and … well, NO! New meanings, discovery—how else do they happen? Mainly after some sort of breakdown … As time goes on, I feel like I can predict the position each person is going to take on an issue and how each of the rest will react. So what’s the point? There’s an excitement in the mayhem that happened. …Who knows? Maybe there is a method to my madness in even entertaining Ron’s proposal. His becoming a member of the team would shake up the stalemate between Art and Howard. Martha would have a new target to size up: Is Ron open like her and Art, or closed like Ian and Howard? Ron is going to surprise them all. He will breathe life into the meetings. It certainly will get exciting again. For me, anyway.

DUNCAN: Organizations don’t know what to do with types like you. They feed off of your energy, imagination, and vision, but all along they know you don’t belong.

RALPH: It always comes back to that … me wondering whether this or any organization is the one for me.

DUNCAN: You think you’re making a decision about your future, but in fact the organization is also making a decision. The system evolves all the time, and its ability to adapt is always a key factor. One thing about you, Ralph: in spite of your action, impulsive or not, you tend to intuitively know how big and small systems work, and you quickly learn the intricacies of the latter.

AS FOR RON …

Ralph survived the uprising. By the next meeting, the revolutionary dust had settled. Ralph stood by his decision to bring Ron on board, appealing for and getting a wait-and-see, with members meeting individually with Ron before Ron attended his first meeting, two weeks away. Backed by Ian, Martha asked Ralph not to “prepare” Ron for these meetings. Apparently, team equilibrium was restored.

Individual meetings went as expected. Martha smoothly slid from high to level ground. She liked Ron’s complete candidness when, discussing his ambitions, he told her, “You push straight to the heart of the matter, Martha, but just know, some things are private.” At home with her husband, Lance, Martha admitted to being a little jealous. She saw what Ralph valued in the newcomer: his greater commitment to green than hers, and his patient hanging back until he got the picture before stepping in.

Art and Ron talked only about literature and philosophy, also throwing in some Greek and Roman epics, from which they drew analogies to modern wars, business, and governments. Art learned all he needed to know about Ron’s fit and lack of fit at ClearFacts.

Not unexpectedly, Howard and Ron did not “connect.” By unspoken agreement, they kept circling around each other at a level of mutual suspicion that would not go away, not in this meeting and perhaps never. (He’s subtly seeking advantage by making me feel like a “black man,” thought Ron. And Howard thought, I’ve got to be ready. This guy has tricks up his sleeve.) In fact, Ron hadn’t mentioned the fact that his girlfriend, Lani, was a recent hire in Office Asia.

Ian’s opening round surprised Ron: “If our country were in a ‘just war,’ would you volunteer to serve? … An ‘unjust war’?” The ensuing conversations allowed each man equally to get a measure of the other. Ian clearly wanted it that way. Ian’s second round (stepping up as “Sheriff Max” and COO-CFO) tilted the discourse: “How does all you’ve said affect how you deal with ‘just’ authority?” Ron heard the statement in the question. His answer, boldly honest and undefensive, didn’t exactly please Ian, but it earned his respect.

HOW LEADERS BENEFIT FROM SYSTEMS THINKING

A significant number of today’s most influential organizational and leadership theories have shifted into systems thinking. As one of the five core disciplines for learning organizations, systems thinking “helps us to see how to change systems more effectively, and to act more in tune with the larger processes of the natural and economic world.”4 In addition to the existing, well-articulated views of why systems thinking is so relevant and essential for organizations in today’s complex world, I offer my own tally of the benefits of systems thinking for leaders today.

Guiding Development and Change

Organizations evolve and change because their external environment changes in response to new technologies, new competition, changing markets, and so forth. Internal forces—the introduction of new people, new processes, and ways of doing things and the evolution of the internal culture itself—also play a role in organization change.

Leaders and those with whom they surround themselves are responsible for steering their organizations through good times and bad. Leaders’ understanding of external and internal forces needs to be systemic, inclusive, and holistic if there is to be effective strategic planning, management practices, and leadership development. It is a monstrous challenge to know how all the major parts—processes, teams, divisions, the rank and file, both formal and informal thought leaders—are functioning within themselves and among one another; but leaders who reflect on “how the system is working and might work better” are more likely to succeed.

Developing a “Leadership System” as Insurance Against Inevitable Crises

Organizational crises are inevitable. Most leaders surround themselves with handpicked lieutenants. If they have acquired systemic wisdom, they know better than to choose only like-minded bedfellows. Most cloned groups are poorly equipped to respond effectively and dynamically to crises.

By contrast, consider what I call a leadership system. In it, each leader is equal in mastery to the nominal leader but different in character from the other leaders in the group, and each is prepared to step up as virtual leader, bringing to bear capacities that are best suited for comprehending and managing the crisis at hand.

Solving Problems and Making Decisions with Fewer Mistakes

Referring to medical errors in hospital emergency and operating room systems, surgeon Atul Gawande has written, “Not only do all human beings err, but they err frequently and in predictable, patterned ways.”5 His point pertains to business systems, too: “Disasters do not simply occur; they evolve in systems.” Faulty systems have built-in defense mechanisms that cover over faulty decision-making processes and structures.

Just as there are fatally bad doctors and good doctors who go bad, there are bad leaders and good leaders who go bad. A leadership system like the one I just described is an organization’s corrective for the latter. Good leadership systems are specifically designed to catch (early, before they do damage) the corruption of moral values that leads to many mistakes in business judgment and decision making.

Increasing Capacity to Communicate with Multiple Audiences

Thinking systemically enhances a leader’s capacity to communicate with multiple audiences. In the purest sense, thinking in terms of system means according “the other” a value equal to self. This is not to dispute the value of roles, status, hierarchy, and power differentials. But the ability to think neutrally about the system—and thereby identify the bigger picture and understand the relative importance or triviality of one’s position and place at any given time—is as useful as it is humbling.

If your goal is artful, effective communication, then knowing how systems work is a good first step. Nurture an ability to step back to a systemically neutral place where you can view the whole, leaving yourself behind as one part of the system. Also nurture the ability to glide back in to engage as a participant.

Having a Life

It may seem odd to propose that maintaining a systems perspective is critical to “having a life.”

Work systems are powerful. They put bread and butter on our plates. They define us as worthy or unworthy. They inflate or deflate our egos. For many, they are a home away from home, and for others they are the chief source of affection, intimacy, and love. As for work systems’ harmful effects, leaders and would-be leaders are, curiously, more vulnerable than the rest. Workplaces can absorb, use up, even kill their leaders. Although having a systems perspective cannot promise immunity, it is a safeguard against the temporary losses of sanity that literally or metaphorically “kill” leaders. The endangered ones lose sight of the whole. The boundary between the self system and the work system dissolves; then intimate relationship systems and family can suffer, go unattended, or shrink in significance.

- Do you know how you came to choose this system?

- Is there a story behind this choice?

- Were you raised in an open, closed, or random system?

- Is your current personal choice the same or different from the one that prevailed in your childhood family?

| Operating System | Rank |

| Open | _____ |

| Closed | _____ |

| Random | _____ |

- The extent to which the nominal leader’s preference influences how the group’s work gets done

- Clashes between members based on different system preferences

- How your own preferences affected your inclinations in terms of whom you supported and did not support

- The military

- An R&D department in a technology firm

- A medical team in a hospital operating room

- A pilot-copilot team

- The Vatican

- A university philosophy department

- Are there any disconnects?

- Is there a match or mismatch between your preferences and the group’s?

- How does this affect your performance and how it is perceived by others?

- Were there miscommunications or clashes between members based on different system preferences?

- When the group was most stuck, were competing speech acts in play—for example, a move in open meaning versus an oppose in closed power?

- How did your own preferences affect your inclinations in terms of whom you supported and did not support?

- What did you do about this?

- How did it affect your relationship?

- Did you openly discuss the issue?

- Does your practice guide you in how to deal with this kind of issue?

- Can you identify a leader who reflected each of the three operating systems?

- Describe each of these leaders in terms that highlight the way he or she tended to operate.

- As you consider your general opinion of these leaders, how did your rating of them reflect your own operating system preference?

- What did you do about this?

- How did it affect your relationship?

- Did you openly discuss the issue?

- Did you downgrade your evaluation of the report strictly on this basis without knowing you did?

Notes

1. If you are not already familiar with systems thinking or would like to read more about how structural dynamics fits in with other systems approaches, see my book Systems Theory for Executive Coaches, 2004 (available through the Kantor Institute Web site, www.kantorinstitute.com, or through Meredith Winter Press, www.meredithwinterpress.com).

2. Important contributions to this field have come from Chris Argyris’s extensive work on organizational learning and routines that disable learning, and from Peter Senge’s system archetypes. Argyris, C., and Schön, D. A. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1978; Senge, P. M. The Fifth Discipline. New York: Doubleday, 1990.

3. What Norbert Weiner called “feedback of a complex kind.” Weiner, N. Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1948.

4. Senge, P. M., Kleiner, A., Roberts, C., Ross, R., and Smith, B. The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization. New York: Doubleday, 1990, p. 7.

5. Gawande, A. Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002, p. 63.