chapter SIX

Level IV: Stories, Identity, and Structured Behavior

We move now below the behavioral profile to Level IV of the structural dynamics model. (Again see Figure 1.1.) The best way to describe the relationship between Level IV and the behavioral profile may be to say that Level IV takes us down to some major sources of the profile. No single concept is more ubiquitous in our lives, and none more difficult to unravel, particularly in close relationships, than what is commonly called identity; and no question is as great as Who am I?

Humans answer this question with stories—a surprisingly small set of them. These identity-forming stories are the essence of Level IV. The stories and what we make of them accomplish two fundamental human needs: first, they allow us to form a coherent sense of self that distinguishes us from other human entities; second, they give each of us a recognizable voice that allows us to be heard, understood, and responded to in human communication.

Preceded by much distinguished thought and research into identity, this book will limit itself to identity as it relates to communication in close, meaningful relationships. Reading the Room posits four stories as the bases of adult identity. This chapter focuses on two—the childhood stories of perfect and imperfect love, both typically conceived in early childhood. The young-adult hero myth, conceived between adolescence and young adulthood, is fully treated in Chapter Nine. The fourth story, the morals-shaping story, is cumulatively arrived at, originating in childhood, as Kolberg, Piaget, and Freud have established, but becomes vital, structural dynamics asserts, in mature adults, particularly those in positions of power.

Structural dynamics views leadership (which includes parents and others who model right and wrong behavior) as preeminently a test of moral character. On a daily basis, leaders make decisions that have moral consequences for the lives of others. Part Two of this book exhaustively deals with prototypical leaders’ moral sense and capacity for moral action.

However, with the possible exception of Howard Green and a summary of his adult, story-based character flaws (Chapter Ten), I do not posit the existence of a foundational story with structural offshoots as with the other three identity stories. This is because I’ve not completed the kind of live, out of the laboratory, empirical research I’ve done with the others.1

IDENTITY IS LINKED TO LOVE

Most experienced coaches have had training or experience that has led them to realize and acknowledge to some extent that love is vital to everyone, including leaders, and is an essential part of the human conversation. But many business leaders seem to regard love as the “L word”—irrelevant or inadmissible in questions about their working lives. Part of the challenge of Level IV is seeing how and why love is the one universal, the one thing everyone wants, indispensable to the deepest understanding of what happens even in the business “room.” In this chapter, that challenge is on.

I will show how coaches and leaders greatly enhance their abilities by fathoming their own identity-forming stories. Although it is not always available to them, leaders and their work can also benefit dramatically from knowledge of the identity stories of others in the room, especially when individuals and groups enter the “high-stakes” territory we will explore from Chapter Eight onward. For the sake of your understanding of structural dynamics, the ClearFacts case will reveal more of the identity stories of the various characters than any one individual is usually likely to be privileged to know.

Being loved is the response all social and socialized human beings crave most. This desire, our theory claims, is derived from four questions that haunt us from childhood through maturity and beyond:

We work so hard to define and find love and to defend it against assault because identity demands it. I explored this issue in My Lover, Myself, 2 a book based on foundational study of families, as described in the preface of this book. No less than other mortals, great leaders seek to answer these questions; and the inseparable relationship of identity to love is crucial to understanding leaders and leadership. What distinguishes leaders from the pack is the special, often impossible tests to which their special responsibilities subject them. And unfortunately, many leaders give up on love at home and seek it in the workplace, where, in the form of rewards (money, power, and intramural or extramural sex), it abounds.

PERSONAL STORIES AND COACHING

When I first introduced structural dynamics to consultants over twenty years ago, some were skeptical about eliciting childhood stories outside therapeutic settings. Others thought CEOs would neither cooperate themselves nor approve the practice for other people under their supervision in the company. Both concerns proved overblown. Once trust was established, CEOs welcomed the insights their stories provided, and enthusiastically recommended the procedure for key people in their ranks.

As the field of executive coaching and its practitioner training has evolved, the use of stories and material from the past to inform and guide intervention has assumed a key role. Richard Kilburg at Johns Hopkins University has provided research and practical guidelines for using psychodynamic material in executive coaching, and has added supporting evidence to my earlier research:

In short, unconscious material in the form of past experience, emotional responses, defensive reactions, underlying and unresolved conflicts, and dysfunctional patterns of thinking and behaving can contribute to poor leadership and consequently to decreased organizational effectiveness. … The nature and complexity of these structures, processes and contents have been widely explored both clinically and scientifically … and their ability to influence conscious behavior has been widely established. … Professionals who work with executives in organizations are foolhardy in the extreme to approach their work as if such forces did not exist and did not affect the people with whom they work.3

My experience as a practicing consultant, executive, coach, and trainer of consultants continues to confirm Kilburg’s observations.

However, exploring a leader’s past can lead underqualified “clinical consultants” into dark territory beyond their training to handle. The key word, of course, is “training.” The methodology is detailed in a chapter in the Casebook of Marital Therapy called “Couples Therapy, Crisis Induction, and Change” and in My Lover, Myself. It has been successfully taught to scores of consultants. In our ClearFacts story, Duncan Travis is one of those.

Regardless of a coach’s level of expertise, it is important to remember that a coaching intervention can be successful without delving into the story level of structural dynamics. As I mentioned earlier, stories are powerful factors in one’s behavioral profile, but exploring them is not always warranted or appropriate. But where such exploration is the appropriate path, stories do provide a rich source of data for change and growth. From discovering one’s own critical stories to diagnosing the unsuccessful interfaces in one’s organization, storytelling experience is a means to more fully and deeply come to know oneself and express that knowledge with others.

STORIES

Stories are the primary means by which human beings make sense of the world and themselves in it. Each of us is a story gatherer—from birth observing and selecting images as basic references for our ideas about the world, what satisfies our hunger, makes us happy, brings us pain. We experience external events and, over time, contextualize them in narrative structures with themes, plotlines, and actors.

Story is the device that allows us to store, organize, and retrieve meaning from the images we choose to remember. Images are memories, pictorialized representations of events—thoughts in visual form. They involve the self and at least one other person. Every individual’s patterned behaviors, his or her characteristic tendencies in relationships, as in families and teams, are based on these images. 4

Our individual wealth of story (and image) not only shapes our behavior but also helps us share our impressions with others. Wherever people converse face-to-face, a story will ripen and unfold that defines and differentiates that gathering or group from other entities.

No one needs to be taught how to build a story; stories develop in us systemically over time. Story formation is an innate activity in our connecting with other human beings, sharing key experiences, and saying who we are—our identity. Of course, not all of our stories (or even all of our early ones) are identity forming. Starting at age five or six, and continuing into young adulthood (by which time our identities are well established), we gather, store, and tell our most formative stories.

STORIES BEHIND A BEHAVIORAL PROFILE

Once a leader, such as Ralph, is familiar with the language of structural dynamics, he can search his memory for the four stories that define him and his typical behaviors, including various expansions that account for whatever breadth of behavioral range he commands. Coached by Duncan, Ralph might explain his penchant for random systems with a story something like this:

• • •

My random leaning is at least in part a reaction to a rigidly closed father who was terrified of my status-quo-defying, creative instincts. My favorite professor as an undergraduate had long hair before it was fashionable. “Anything goes,” he told us. “What you argue as true is okay, if you can make enough sense of it to stand up to me when I call on Socrates to challenge its structural logic.”

• • •

Such a story from Ralph would also help account for his strong preference for meaning. Ralph could also identify and tell stories that affirm his affinity for Martha and Ron, his tolerance and respect for Ian, and his dislike of Howard. From your work in Chapter Five, you should also be able to identify, tentatively at least, the system preferences of people who begin stories with statements like those in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1Story Openers and the Preferred Systems They Suggest

| Story Opener | System |

| What I prefer is a traditional, ordered world of a pope, over the chaotic world of a crazed artist. When I was an out-of-control teenager, my priest all but saved my life when … | Closed |

| My father was tighter than the nuns at the school I attended, and my mother was the family’s atheist freedom fighter. They fought constantly. My wife and I set out to avoid the pitfalls of both those regimes. Our kids have a voice, but we have the final word. | Open |

| I remember with nostalgia my father’s arrival precisely at six every night, and the comfort and sense of security it gave me. I want that same sense of order in our lives. Let me tell you what that was like. | Closed |

| I watched the calendar for my aunt’s monthly visits like other kids watched it for Christmas. Every visit was a circus of fun. Her stories inspired mine. I learned from her what was possible for women who wanted freedom from all constraints, a willingness—no, a necessity—to break existing rules if it came to that. | Random |

TWO CHILDHOOD STORIES (PERSONAL MYTHS) OF LOVE

There are two basic childhood stories of love: a story of perfect love and a story of imperfect love. Each of us develops both stories in ourselves, with individual variations. The stories are as “true” as any of our vital childhood memories, but told with larger-than-life, rather fantastical characterizations. From hearing hundreds of these stories, I can attest that in certain dramatic moments of “telling,” this is how they are reexperienced: extravagantly emotive, romantic, exaggerated, fairy tale, mythic.

The story of perfect love comes first. In the years immediately following birth, the expectation of pure, unending, unconditional, Edenic love persists in the growing child. The mother and those around her strive to meet all the child’s needs and thus reinforce the expectation. This story that we will always have a source of perfect love is documented in a selection of positive memories that are both recollected by and told to the child.

In time, however, harsh reality inevitably serves up insults and injuries to this perfect environment. Eventually, contradictions—ordinary ones like illness, discipline, fears, and angers, and more serious ones like neglect, humiliation, and abuse—will conspire to challenge this story and inspire the child to come to terms with the imperfect nature of love by telling a second, competing story about love. This story of imperfect love may be even more poignant and compelling because of its almost mythic energy, its power to rekindle deep feelings of loss or pain, and a melancholic disappointment in a breach of the story of perfect love. Because it is created by a child—roughly between five and fourteen, we have learned—it has some of the character of fairy tale, with heroes and villains and themes of lost innocence, sudden awakening, betrayal, and disappointment.

When many stories of imperfect love are intelligently probed, the stories’ universal character is strikingly revealed—they have the same narrative structure, by which I mean that they all tend to contain at least several of seven recurring features, which we will explore in detail later in the chapter. As adults we may have more choice, but as children we seem to have little choice but to see the world in moral terms. In our early striving to make sense of our family world, we assess ourselves and others with the belief that a behavior or person is good or bad, right or wrong, strong or weak.

To the child, even trivial affronts can be experienced as major assaults. Setting the stage for his or her own story of imperfect love, every child thinks,

• • •

I am weak and defenseless compared to my parents. I know that once, a long time ago, I was truly and perfectly loved, but it is only a memory. Am I loved now? How can I be sure? Why is it that, when I cry at night because I want to be with them longer, they get so impatient and angry? There! It’s happened again. They hate me. They probably want me to go away or die.

• • •

Thus, as children we naturally dramatize our claims, and each offense—whether trivial, outrageous, or atrocious—is stockpiled in an archive of complaints against the stronger, more powerful family authorities, ready to be shaped into a story of betrayal. The stage is now set; the child, having absorbed the structure of story from stories read and told, is ready for her first creative act, writing a story of her own, the story of imperfect love, her personal myth. As mentioned, these mythically toned stories have seven recurring features:

A story is ripest for telling when events in the present raise resonant themes from the past, which rise to just below consciousness. From there, on provocation, they make their way “into the room.” When one partner says to the other, “That’s not me you’re describing; it’s your mother,” he or she is capturing this moment.

Anyone who has been in a key long-term and especially intimate relationship has probably experienced the typical repetitive, cyclical struggle, disagreement, or fight that results in an impasse, but to which both combatants return for yet another bout whenever a thematic trigger is pulled. I have described this cyclical pattern and the damage it does in several publications.5 And there is no want of examples in my consulting and executive coaching experience, nor in those of colleagues.6 You will see it in the following dialogue between Martha and her husband, Lance. When a coach (like Duncan) or a mate (like Lance) witnesses a ritually told tale spin round and round a repetitive theme, the story (Martha’s) is ripe for the telling.

MARTHA AND LANCE—THE RITUAL FIGHT

I will use Martha’s relationship with her husband, Lance, to illustrate the features I have just introduced. I will also bring in the concept of ritual impasse (noted in the section “Structural Patterns Mold Behaviors” in Chapter Two).

The Quarrel

Martha had gone to Asia on a business foray, one purpose of which was to do a little detective work about the anonymous e-mail that Ralph had revealed (Chapter Three). As we enter the scene, she had just flown home, disappointed. She and Lance settled in with a glass of wine, their usual routine after one of her trips and many times a prelude to “welcome home” lovemaking; but this time Martha was obviously tired and out of sorts.

“Lance, I was so sure something was going on there, or that people would talk,” she said, “but not one peep. I feel so empty.”

With this in mind, Lance hazarded something he intended as a means of lightening Martha’s mood: “Well, maybe we need to freshen your tank.”

Martha glared. “No stupid humor. I failed.”

Missing a cue, Lance persisted, “Look, you’ve been obsessed with this thing. Let it go.” But he knew as he said that it he’d made a mistake; he’d pulled a familiar trigger.

“You know my need to know,” she replied. “Dammit, you sound like my sister.”

Lance managed to duck and recover, sensing now that what she needed was not a muse but comfort. He listened, letting her talk until she cooled off, then, taking her hands, lifted her to her feet, embraced her with a tender touch, and led her to the bedroom.

On other occasions, the sex might have broken the tension of the skirmish. This time, the aftermath was an explosion into their own and all-too-familiar battle. Rising for another glass of wine, Martha caught the glow of Lance’s computer, looked that way, and saw on his work table some sketches for his latest paintings and, next to them, photos of the nude in the sketches.

Suddenly beyond fury and outrage, she hurled her glass at the floor and cried, “You’ve gone too far! Again! And lying about it? The one thing we don’t do is lie!”

“Again.” “Too far.” “Lying.” The words began a speech that pressed every trigger Martha knew he possessed. In truth, Lance had written her an e-mail telling her of his need for a model, but anyhow she’d been away, so he hadn’t actually sent it. So, all right, he thought, technically I broke our pact. But never mind all that. So Lance, too, entered the war zone. Resonant themes of his own ignited, the recycled argument ramped up.

Ever since that homecoming tiff—the “Asian affair,” as they came to call it—the argument resumed now and then, each time leaving them exhausted with self-disgust, as happens at the end of most ritual battles. Judging by her performance at work and nearly everywhere else, one would have thought Martha, the master bystander, most capable of standing back, but on these occasions she couldn’t.

At the close of one of those cyclones, however, Lance managed to step back and say to her, “Martha, please let me speak. Before, you haven’t minded my using live models. What got to you this time was my not telling you in advance. Consciously? Unconsciously? Too lonely to admit? Okay, there’s no excuse. No matter. I broke our sacred rule. But now, just let me make up for it.”

To which she agreed. And when the conversation leveled to normal, she also admitted the keenness of his observation. Yes, he’d triggered her memories of disappointment and anger. But those guys at ClearFacts did, too! And it was this compounding of situations that turned her mind toward talking a few things over with Duncan, the team’s ultimate, unofficial, and surely confidential bystander. If that doesn’t work, she thought, I’ll call my old therapist!

Lance’s Past and Present

We are focusing on Martha, but Lance’s stories matter also, as there are two people and thus two story sets present in every ritual fight. We sketch his here enough to provide a context for his behavior.

Lance’s father had been an artist. A small circle of art aficionados considered him a modernist genius, breaking new ground on his own path. The rest of the art world disagreed, and in fact he didn’t “make it.” Lance’s mother sided with that “rest of the world” and was ultimately even less sympathetic toward her husband. Lance, the son, an aspiring artist himself, revered his father’s relentless perseverance and fully absorbed his deathbed advice:

It was worth it, Lance—every moment. The “rules” will strangle your creativity if you let them, son. Break those rules if you believe that doing so adds something to the world!

Breaking society’s and “the academy’s” rules for a higher purpose was Lance’s personal and artistic slogan and mantra, and Martha admired him for it. Also, she was intrigued and aroused by Lance’s defiant claims to fun (“Let’s fly to Paris for a couple of days; we’ve been working too hard”). But the rules they shared about monogamy and telling the truth were clear, she thought: “No deceit: if ever there is reason to stray, we tell the truth and talk.”

Some of Lance’s peers considered his work pornographic and, from a purely artistic point of view, professional suicide, but Lance argued that it was an artist’s responsibility to challenge the status quo; he must push the margins of taste in his work—yes, especially the boundaries of sex: “You see it in novels; I’m trying to do it on canvas.”

Martha supported Lance in this, but with a caveat: “Yes, as you artists say, ‘Eros animates the brush,’ but that’s also a sexual euphemism. It’s an unacknowledged excuse for artists to screw their nude models.”

“Not this artist,” he pledged.

Martha’s Childhood Story

When Martha met with Duncan, several of the previously mentioned features that show up in all childhood story narratives of imperfect love were revealed. Here is a portion of their conversation:

MARTHA: My mother? A year-round frost. She ran the help and my father with an iron fist. So for me, my father was more than charm and class; he was mother, uncle, brother, and best friend. He knew how to hold a child like a feather. If you’re wondering, Duncan, it wasn’t sexual, but deep, the way the best sex is … (Later she told Duncan she was pulling his leg when she said that.) … more like a snuggly. Sinatra, that’s my dad—his touch. Lance is the only man who’s ever come close to a touch like that. It’s partly why I married him. But my dad betrayed my trust. He had a way of making a nauseating truth seem appetizing. Lance has that in spades, too, another reason I married him. But he’s never lied until now.

DUNCAN: You seem to say you got through that scene with Lance all right, but let’s look at the two themes it unearthed: truth telling and betrayal.

Taking steps he’d been trained in using, Duncan led Martha into telling her story. When telling their childhood stories in skilled hands, clients tend to reexperience emotions that drove the need to create the story in the first place. Duncan went slowly in taking Martha from her own strong feelings to new insights connecting the past and present with Lance.

Her story, which echoes the sounds of fairy tale and myth, is the birthplace of toxic themes that can unravel all humans facing extreme pressures and crises (see Chapters Eight and Nine). Like the sample illustration that I have also included (Figure 6.1, following the story), the voice in which I tell the story that follows conveys more accurately how the adult is experiencing the telling than any more “adult” and objective-sounding rendering would do. In the immediate moment of telling, grown men burst into tears, mature women tremble violently. When this moment passes, a trained consultant can help the storyteller tease out the critical themes, plot lines, and structures that are impacting their work and personal lives. These I interweave into the story.

Figure 6.1 Martha’s Childhood Story

• • •

My mother was a stately, powerful queen who married a rich and noble man, then ruled him like a child. She believed in the family, as devotedly as some do in God.

Whenever she saw me or my sister or brother in danger of leaving “the path,” she’d remind us, “Build your house on high ground, on solid rock, and within its thick walls rule firmly, for the family is the path, the source.” I felt safe and secure in this big house—my mother’s sacred realm—with its servants and familiar observances, ceremonies, and traditions.

Yet my gentler father was also a source of strength to the whole family, more than a pet! He was our guardian and the rock on which our house was built.

By age ten I had discovered a strange and at first frightening (because it glowed mainly at night) power in myself. If I surrendered to its magnetic pull, I could see the unseeable, know the unmentioned. I discovered not just worms and bugs buried under rocks, but dark truths and other “not to be’s” with my power. When my mother often called me “too curious, child,” she came close to exposing this secret to the light of day.

But then my power and I became friends. My curiosity was special because it beckoned from a life of its own inside me. At certain times—night mostly—it left my body and presented itself in a faceless, adventurous, and magnetic form I could not resist. When it said, “Come with me,” I leaped to obey.

I kept knowledge of this power from my siblings until the day I had to share it. I was the middle child. My older sister was weak and afraid. As a young boy, my brother “Junior,” four years younger than I, pretended he didn’t exist. As a young child, he kept to himself a lot, and was all but raised by an au pair. Even later, he added little to the household. He was an “accident,” or there was some mystery concerning his birth. I cannot say how I came to find these things out. Knowing would hurt people anyway. Did Junior know?

Sissy’s never-strong will was crushed when she was severely punished for reading Mother’s diary. Why? Was there something to hide? She was thirteen and I was ten and had just discovered my secret power, which made me even more inquisitive about Mother’s private life. Mother intimidated Sissy. I was unafraid.

My mother and I loved each other but sparred a lot. She respected my spirit and decided to train me to be a strong woman, her successor. She tried to school me about “man’s inherent and unconquerable weakness.” I listened, watched, decided to make up my own mind, especially about my father, whom I worshipped. My nighttime intuition said she didn’t love him as a man. Why did he not fight for his rights? What was wrong?

I became obsessed with championing my father, and Mother always firmly resisted: “Please don’t sell him to me, dear. Your grandmother, my mother, did that before your father and I married, and she was dead wrong.” But I wasn’t so easily deterred. Wicked queen! I thought. In turn, Mother, reading my mind, reprimanded me for insolence. But I knew she had no intention of crushing my spirit, as she had Sissy’s.

In my nightly wanderings, I knew in my bones that something was being concealed. I watched Father giving Mother plenty of room, especially on Wednesday nights when he stayed over at the club. I charged my mysterious power, Lift the veil. Break the seal. Speak out. When these incantations failed, I vowed one night to bring whatever it was into the light. It was Wednesday night, and Father had left for the club.

I went first to Sissy’s room, announcing, “I’m going to Mother’s room.” Sissy was speechless, turned red as a beet: Mother’s room was strictly off-limits, even to Father. “Come with me,” I begged. Sissy turned white as a sheet. I waited. She shut her anguished eyes and silently rolled her head from side to side.

I left and tiptoed down the hall toward Mother’s sanctuary, quiet as a hunter. I heard the man’s voice, but did not see him. It was not Father’s voice. I wanted to flee, but then the man’s throaty sounds were joined by my mother’s soft, honeyed sigh, and I could not tear myself away.

When I finally made my way to Sissy’s room again, she lay there frozen, as before. Still gripped by terror, she whispered, “I dare not let you speak. Leave me. I beg you.”

Next morning I rose early and put on a white and black skirt, as formal as Mother ever was at breakfast, and went straight to Sissy’s room.

“Have you lost your mind?” she said when I revealed my plan.

“Do truth and injustice mean nothing to you?

“But do you know what you are getting into?” Sissy pleaded. She reminded me that Mother was renowned for her distaste for stealth, and how Sissy herself had been severely punished merely for “stealing a look” at Mother’s diary.

I began to tell Sissy how much I needed her at my side, but she would hear no more and fled to school without breakfast. As usual, Father arrived home from the club in time for breakfast.

“I have something to say about what happened in our house last night,” I gushed, as soon as Mother joined Father and me at the table.

Reading my mind, Mother slammed both palms down hard. “William!” she shouted. Father leaped up, as if in fear, or rage.

“Why are you angry, Father?” I said.

His voice quivered. “Please come with me. To the library. Now.” Once we were alone, he demanded, “What are you about?”

“I’ve come to tell the truth. I want to restore you to your rightful place.”

“No, no, my child … it is not for you to open the light that could harm us all. You should leave well enough alone. What’s dead is dead.”

“But Father, what is dead can be reborn. Where there is vinegar there is sweet honey. Where there is sorrow there can be hope.”

“In the name of God, I must forbid you to go any further with this.”

“But what I do, I do in the name of love.”

“What I ask, I ask in the name of love.”

I was seized by what I know now to be compassion. But I was deeply confused as we walked back to the dining room together, Father’s arm resting lightly on my shoulder. I never felt more alone.

• • •

“Good,” said Duncan when she was done. “My job is to help you explore how themes in your story carry over into themes at work. Here’s one idea. Your distrust of Howard works two ways. Because of your sensitivity, you are probably on to something in your suspicions about what he might be up to. But oversensitivity can cause unnecessary trouble …”

Figure 6.1 is an artist’s visualization of Martha’s childhood story, which a coach like Duncan would give her to keep.

A CHILDHOOD STORY’S NARRATIVE STRUCTURE

Martha’s story contained several of the common features of childhood stories, which we will now explore in greater detail.

1. The Hurtful Monarch

Usually, the hurtful monarch (either the father or mother) is the dominant parent, the star protagonist in the storyteller’s view of the family’s dynamics. In some cases, some other adult (an uncle who perpetrates incest, for example) or a sibling plays this role. The child’s “hurt” can result from cruelty or coldness or withholding, depending on the story maker’s emphasis and interpretation. In Martha’s story, her controlling (closed system) mother bids high for the part, but Martha’s father shares the role because Martha is even more disappointed in love by her father’s acceptance and “slavish” (Martha’s word) support of his wife’s deceit, and because of Martha’s complete adoration of him as the more engaged parent.

2. The Silent Conspirator

Silent can also mean silenced—not “there” in time of need. Couple dynamics are most certainly at play in this most devastating of mover-follower structures. We saw these dynamics in Ian’s story, and we will in Ralph’s.

The silent conspirator in Martha’s story, her father, speaks kindly, attentively, and lovingly, but he does not speak the truth, the truth of Martha’s “discovery” at a crucial moment of confrontation. It is this resoundingly loud, unexplained silence that is too much for Martha, the object of his affections. Thus she adds “betrayal” to her litany of hurtful themes.

3. Resonant Themes of Guilt, Disfavor, Sadness, and Deception

In important interactions, resonant themes such as Martha’s theme of betrayal are what animate partners and colleagues into cocreating ritual spirals. The childhood story, not truth or reality, names the resonant themes just as a playwright instructs a director and actors about the tone, mood, atmosphere, and thematic focus of a play.

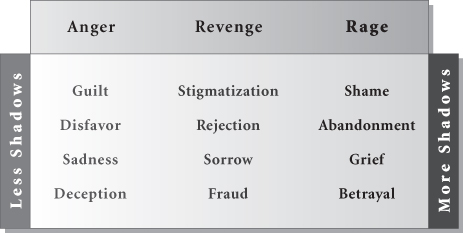

Themes running through childhood stories range from universal to particular. At the universal level, we find broad themes of loss of innocence, sudden awakening, departures from paradise. At a deeper personal level, themes exist as emotional states that fall somewhere along the five continua shown in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2 Birthplace of Themes: Four Thematic Continua as Influenced by Degree of Anger

Each of the five dimensions in the figure shows three terms along a continuum of greater intensity from left to right. My use of the term “greater intensity” is meant to suggest that adults telling their childhood stories speak of hurt or pain or harm that ranges from lesser to greater along the same continuum, and that the intensity of felt damage contributes to the depth of the shadow (discussed further in this chapter). The venom expressed in “love quarrels” can be traced to the anger-revenge-rage continuum, which interacts with each of the lower four sets of themes, adding fuel to burning fires that are ignited in close relationships over issues of identity, love, and reward. Thus the darkness of one’s shadow is a factum of the intensity of the hurt-pain in each of the four continua conjoined with the intensity of the anger-revenge-rage continuum.

I do not suggest that the five dimensions in the figure are definitive or necessarily exhaustive. They are speculations based on my long experience in clinical practice and on my habit of conceptualization. Their scope is intuitive, deductively constructed, and therefore imprecise. Besides, I am no match for the dramatic ingenuity of kids in inventing their own themes—being excluded or not being number one, for example. Could these clinical speculations be put to empirical test? Definitely, and they should be.

When we look at it from left to right, Figure 6.2 might suggest a continuum from health to pathology, but structural dynamics resists the unfortunate tendency of experts to define increasing numbers of behaviors as pathological. The shadow of our darker side, as much as we might deplore it, is universal, and we therefore cannot loosely view it as pathological. I suggest that rather than pathologize, apologize, or find excuses for your shadow, you get to know your own and take responsibility for it.

The themes at this personal level are particularly useful in understanding your shadow, a topic I’ll discuss more thoroughly later in this chapter. Our shadow is a hidden expression of our fear that we are unloved or unlovable, which we turn on our self or on others. The strength of a person’s shadow depends on where her psyche positions the self along each continuum in Figure 6.2.

Duncan had a good sense of Martha’s vulnerability in the area of deception-fraud-betrayal. Martha’s colleagues could trigger reactions of different strengths along the anger-revenge-rage continuum, for example: anger at Ralph and more at Ian; feelings of being defrauded by Howard, to the point of rage. It would seem natural to Duncan that the child in Martha felt betrayed by her acquiescent father, whose love she knew and valued, and by Lance, to whom she turned, as I think we all do in our choice of mates, to make up for the child’s lost love.

4. Melancholic Disappointment

In nostalgia for the past, adults weave together remnants of the two childhood stories of love. Perhaps this is what accounts for the story’s bittersweet quality: the “bitter” a reminder of betrayal, the “sweet” for the memory, or dream, of perfect love. For with the story of betrayal comes the child’s first real disappointment in love. In childhood, it is experienced as a vague and for many an overbearing sense of melancholic loss of innocence. We carry this memory of disappointment with us throughout our lives. When our search for the ideal lover has at first paid off, but in erosive time fails or threatens to fail, we reexperience the child’s sense of melancholic disappointment as another betrayal, doubly felt for the seeming fact that love has failed us twice. But then most of us gear up for another try, even after the ritual impasse has settled in.

5. The Truant Hero

The coconspirator’s failure to challenge or balance the powerful monarch leads the storyteller to seek or, more likely, wish for the truant hero—that figure in the real or imagined life of the child who, if he or she would only appear, would do whatever it takes to make the story of love come out right in the end, as in most fairy tales and many myths. But alas, in the childhood story of imperfect love, this hero does not appear. Some children actively seek this hero as a real-life person. Most, however, rely on fantasy and fantasized rescue. Until! Until, older, they find themselves in two key relationships—one with an ideal lover and the other with an ideal partner in a close relationship at work (both of which, I insist, are about “love”).

It is well known, to those of us who have attempted adult love, that we place an impossible burden on these partners. We expect them to bring closure to the story of imperfect love and, by the by, make it possible for us to reclaim our right to perfect love.

Thus the truant hero plays a prodigious role in our most significant relationships in adulthood. But in childhood, for all the child’s wishing and imagining, the truant hero remains on the run. With his or her failure to appear, the child is left with a deep sense of longing and yearning.

6. Longing and Yearning for the Ideal Mate

As the previous discussion suggests, in adulthood, our longing for a truant hero turns into a keenly double-edged yearning and search for the ideal lover, someone with precisely those heroic qualities and characteristics that can do brave combat with and slay the monarch or any source of hurt. In the work arena, we seek a similarly close relationship. The love and work phenomena are different only in intensity, not in their basic nature.

7. The “When I Grow Up” Hero

In the period between the story’s creation in childhood and our first serious sallies into the big world in young adulthood, we seek credible answers to two fundamental identity-forming questions: Who am I? and Who will I be when I “grow up”? Thus incubates the heroic self and the “perfect lover’s” heroic type. (Who will love me as I want to be loved?)

Beginning with such vague queries as Am I loved for who I am? Do I know who I am? we gravitate to such questions as How shall I shape my own adult identity? What kind of noble, heroic self will I bring to the world? What will the world love me and reward me for? Roughly between ten and twenty years of age, we search the culture for prototypic figures we can emulate. But emulate is not exactly what we do. More precisely, we try on various figures like suits of clothes. We do this until we find one that fits our own behavioral propensities. Thus, what the childhood story contributes to the emerging sense of self is identity, the “who I am” in matters of love. With that in place, the evolving self searches further for “who I am in the world,” the hero who will be rewarded for how he or she performs in high-stakes and crisis situations. Chapter Nine will say much more about the types of hero perceptions we adopt and how they shape our behaviors when the chips are down.

SHADOWS

Part of figuring out the “who I am” in matters of love involves seeking proof of love from those around you, though “seeking love” is not how most leaders would dare to put it. Your shadow “puts you in touch” with that disappointed child, eager to feel loved and “at the ready” to revisit the emotions you felt at the time your story was created, and reacting both to those who withheld perfect love then and those who are withholding it now.

The shadow is the buried memory of the betrayal—the sense of not being loved or of being unlovable—that cuts you off from your best (your loved and lovable) self and the natural impulses you had as a child and still have as an adult. In the puzzling ways of paradox, this is what causes you to act in ways that are guaranteed to keep you from getting what you want most—be it respect, admiration, freedom, fame, or whatever—from your bosses, peers, and subordinates at those times you need it most. Love, or the claim that one did not get enough of it, is the genesis of the shadow; and love, or the reclaiming of what is due, is the shadow’s objective. However, the shadow goes about this in the wrong way.

Some shadows are darker and run deeper than others. The deeper the felt injury, the darker and less accessible the shadow. The strength of your shadow depends on where the psyche positions itself along each continuum suggested by Figure 6.2. In other words, a strong shadow equates to an extreme position—let’s say on the guilt-stigmatization-shame continuum—combined with an extreme position on the continuum of anger to rage. Please remember, however, that the figure is only a framework for how we think about actual events. The story actually told is in the mind of the storyteller, as we know from siblings growing up in the same household and with the same parents who, when they each tell their stories of imperfect love, “cannot believe” each other’s tales.

RON’S STORY AND SHADOW

So far, we have seen small parts of Lance’s and Ian’s story and Martha’s in full. In later chapters, parts of Ralph’s and Howard’s will emerge. Here I summarize Ron’s.

In recent weeks, Ron has firmed up his place on the team as a strong mover and bystander in meaning at the office, and as someone comfortable in affect outside it, having drinks with Martha, for example, and, perhaps ill-advisedly, at dinner at home with Ralph and Sonia. He has also informally built good, but different, relationships with Art and Ian. His relationship with Howard can best be described as cool. However, that will not last. The tension between Martha and Howard will soon increase around the meaning of the “anonymous e-mail,” and in that context Ron’s strengths as a neutral bystander will break down, revealing themes and the silhouette of his shadow hidden in his childhood story.

When Ron eventually puts his story together with Duncan, he will remember experiences when he was about five that have been haunting him, about how he felt when his father held him after a fall, or when the heat went off in a storm and his father wrapped him in a blanket. What he remembers feeling isn’t warmth, but cold in his father’s arms. Maybe, he will muse, this coldness was my father’s way of balancing power with his wife. Maybe it was because the poor guy didn’t have it in him because I was a “mistake,” a black child with white parents.

Ron’s Mother and Father

Adrianne Stuart, daughter of a white Episcopalian minister and wife, was an anthropologist settled in academe after doing fieldwork illustrious enough to earn a very busy tenure, keeping her ideas alive lecturing, attending conferences, serving on committees, and writing. In three words, “Busy and gone,” said Ron.

When it was confirmed that she could not have children, Ron’s mother pressed the idea of adoption on her distracted mate, a token executive in a long-surviving family business. The husband’s mind was mostly on having used the wrong club in a golf tournament. “I need to act on my convictions,” she argued. “I want us to take in a black child.” Her husband did not share her convictions. Worse, he harbored prejudices he could voice post-martini at the club but not to his anthropologist wife. Finally, he sluggishly consented.

So, says Ron, “I was raised by a largely forgotten chain of caregivers, from nanny to au pairs to babysitters. And by an indifferent father left to oversee, reluctantly, the son he never wanted.”

At six, Ron was already questioning, in a bright child’s way, what love was about. He knew his mother was color blind. Also an ideologue, urging him to feel personally, as she did, the injustices against the weak and especially the racially oppressed. He knew she loved him from how he was held on her lap while being read to or being told exotic stories about tribal existence, and especially stories of tribal loyalties. That, to Ron, was what love was about: loyalty. Ron had never seen that motif in his father, but later saw it in Ralph, his “color-blind” boss.

Ron’s mother exacted a pledge from Ronald Stuart senior to take their son along when walking the dog, on at least one of the days when she was away on travels. “He needs to know you love and care for him,” she said.

On one of these walks, Ron experienced a disturbing revelation, his hand loosely held in his father’s large, clammy one. A neighbor approached. Ron saw how the neighbor’s eyes were fixed on those black-in-white hands, the white one seeming to be saying to the neighbor, This is a mistake, and to Ron, and you are it.

A Life-Changing Adolescent Trauma

Ron insists that in his social world growing up he never felt racially marginalized—until he did, painfully. He was attending the famously “right” and liberal secondary Friends School in famously liberal Cambridge, where no one stood out except by looks and brains. And he had both. Formal dating wasn’t cool. But then came his year’s year-end senior dance, the school’s equivalent of a prom. Asked by Rene Saunders, one of his closest friends and confidants in those heavy discussions curious adolescents have about “the world out there,” he accepted with casual grace. He liked the Saunders family, especially the mother.

Sitting with Rene’s father while waiting for her to finish dressing would have been a trial for most adolescents. For Ron, what felt at first like an inconvenience surely became a trial and then an identity-challenging ordeal. The previously friendly elder, sensing sex on the horizon (it wasn’t in Ron’s mind—not yet, anyway), abruptly broke the rhythm of easy talk with, “Sex, Ron, is not an option. Nor is this anything but a date. A date to nowhere.” In this stonily silent racial standoff, boy and man understood each other—relieved suddenly by Rene’s flustered appearance, her beaming mother close behind. “Don’t they make a handsome couple?” she said, but her comment couldn’t reilluminate the darkness cast by the father’s raw moment of truth.

Awakening of an Identity

What Ron did with this was not expected, except by his mother, who cheered him on. Accepted at Princeton, he took a year off and, guided by a black schoolmate who attended Harvard, made his way to one of Boston’s black ghettos, ostensibly to work, but really to do a kind of anthropological research.

The results of this research amounted to an awakening. He saw the collapse of a future for young girls. But he also was impressed by the tough gentle strength of many single moms and by the role of grandmothers and great-grandmothers, women of previous generations who carried the burden of survival, of the “whole race,” it seemed to him.

In this brief sojourn, he also learned firsthand about guns, drugs, and the perishing dreams of so many black males to become an entertainer or professional athlete. Firsthand he learned about the ubiquity of rage among black males and its self-destructive aspects. His conclusion? Getting killed was a clever form of suicide.

Ron knew that before leaving for college, he needed to cleanse himself—not of the rawness of his brief experience in the ghetto, but of his raw guilt over being able to escape. A counselor from his old high school helped him get in touch with his own anger—at the white world into which he was brought, at the contradictions and ambiguities of authentic love, and at his family. He concluded that the best way of passionately claiming his black identity was by “getting ahead, but not at the expense of the oppressed.”

- See if the chapter contains themes in your story that make their way into how you conduct yourself in this and other key relationships.

- Consider the possibility that your story and its themes are the source of what others and you yourself see as your worst behaviors—your shadow side.

- How easy or hard is it for you to take responsibility for your shadow?

- Think of a time or times when, under pressure, your shadow surfaced and took over, with untoward consequences. Was a theme from a past story involved?

- Who are the characters in this story from the past? Do they resemble key people in your present personal and work life? Would you consider that it is not the person but the structure of his or her behaviors that accounts for the resemblance?

Notes

1. The research, now beyond a long period of gestation, is in process. It assumes for now that a working theory that drives moral behavior and its lapses can be tracked to the kinds of stories that appear in these pages. It addresses the following questions: How is adult moral character formed? Is it based on stories? If so, are they structural in nature? And under what conditions are moral behaviors fixed or malleable? But it seemed intellectually remiss in a book on leadership, especially in this era, not to address the moral issues it does—albeit with an incomplete theoretical backup—without stories behind them that are crucial to character, identity, and behavior.

2. Kantor, D. My Lover, Myself: Self-Discovery Through Relationship. New York: Riverhead Books, 1999.

3. Kilburg, R. Executive Wisdom: Coaching and the Emergence of Virtuous Leaders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2006, pp. 249, 266.

4. Kantor, D. “The Structural-Analytic Approach to the Treatment of Family Developmental Crisis.” In H. A. Liddle (vol. ed.) and J. C. Hansen (ed.), Clinical Implications of the Family Life Cycle. Rockville, Md.: Aspen, 1983.

5. For more information, see my “Couples Therapy, Crisis Induction, and Change.” In A. Gunnan (ed.), Casebook of Marital Therapy. New York: Guilford Press, 1985; and My Lover, Myself. New York: Riverhead Books, 1999.

6. In particular, see Diana Smith’s Divide or Conquer: How Great Teams Turn Conflict into Strength. New York: Penguin, 2008.