chapter TEN

Sources and Signs of Moral Corruption in Leaders

A main point of Chapter Seven was the central place of morality in any group story. The last two chapters showed how moral voices, postures, and heroics take over when groups enter high-stakes territory. In such times, every beneficial group—be it a couple or a corporation—relies on the moral underpinnings that its members bring to its interactions to sustain the story. The leadership challenge at ClearFacts embodied in the deeds of Howard Green is basically a moral challenge—a challenge of moral corruption. ClearFacts can survive the crisis of fraud by Howard because other members of the team recognize and act on the situation in a moral way: they recognize the fraud in their midst and do their best to end it. In this way, they enable their company to carry forward its positive narrative purpose. This chapter explores Howard’s signals to the ClearFacts team, as well as other more general signs of moral corruption in leaders.

Is there a way to foresee and ward off damaging immoral acts before an individual is able to commit them? Perhaps not entirely, but one way leaders can limit their occurrence is by building their own strong models of effective and moral leadership and by encouraging the same in their teammates and colleagues. Chapter Twelve will take us through a conscious process that coaches and leaders can follow to fashion a leadership model. Before we go there, let’s see what we can learn about the various ways a leader’s moral behavior can lapse and ways we can detect individual leaders who might in future go astray. We will do this by gleaning some structural dynamic insights into moral and immoral behavior, considering various real-world examples of corrupted leaders, and delving deeply into a structural dynamic assessment of Howard Green and his actions at ClearFacts. We won’t need to go into the details of his actual firing, but rest assured he was fired! Once again, the behavioral profile will be useful.

First, we’ll touch base again with Ralph, his progress toward building some kind of leadership model for himself, and some broad perspectives a counselor like Duncan would want him to appreciate about sources and abettors of moral corruption.

SONIA WATERMAN CALLS A SHOT

Wise coaches make an effort to know as much as they can about the spouses of the leaders they coach. Here we take up the story from the perspective of Ralph’s wife, Sonia.

Sonia knew her husband, and now she knew he was exhausted, working long days reaching into nights on all fronts during those days of crisis and the firing of Howard Green. She didn’t need to hear every confusing detail of his relentless search for new business opportunities, nor every painful resurrected childhood memory that was coming out in his work with Duncan on his own leadership model. When Ralph was this physically and psychologically weakened, she knew what the two of them needed to do, and made no bones about nor took excuses for it.

“We’re going to Italy,” she told him, and did not let him say no.

A good thing, too: after a week in Venice and some leisurely dinners alone, more restful solitude and slow love in an old country villa in Umbria, plus a tour of renovations at the Sistine Chapel in Rome, the two were solid and rested enough again that Ralph was able to reconnect in a positive way to challenges he’d left behind. On the long flight home, Ralph was looking forward to working again with Duncan on Ralph’s own leadership model. As he told Sonia, in line with the moral narrative purpose that ClearFacts stood for in his mind, what Ralph envisioned now for himself was a leadership model he planned to call Moral Leadership. He also wanted to announce to the team a shift he desired in Duncan’s role on the team, from observer to facilitator. And he planned to invite every member of his remaining team—Martha, Arthur, Ron, even Ian!—to have a coach who would take them through the process he’d gone through. From there Ralph himself would move on to something even closer to home that Duncan had recommended to him: a personal model for living. This was a massive step for both Ralph and ClearFacts.

“Sweetheart,” Sonia replied. “You say that Duncan says no firm should be without a narrative. Then shouldn’t couples do the same? If a company without a moral purpose is ultimately doomed to fail, then what’s the fate of a marriage without one?”

Ralph nodded gravely. “That’s why Duncan says we need a model for living.”

“Did you say we? You’d better not mean you and Duncan! This has to be our model for living unless you plan on a life without me.”

Her wisdom wasn’t lost on Ralph. By the time they landed, he and Sonia had reached an important conclusion about what they wanted to do on the home front. They intended to create three narratives between them: Ralph’s own personal story, Sonia’s too, and a blend they would share as a couple. This would not be easy, but they both looked forward to managing it together.

Ralph’s rapture over these vacation epiphanies carried him with a rush into his reunion with Duncan. “Coach,” he began eagerly even before their handshake was over, “I’ve come to two resolves. First, I want to start working on my own leadership model—which, by the way, is going to focus on moral leadership—at the same time as my model for living, not consecutively. I want Sonia involved in my—no, our—model for living. And I’ve started my research, beginning with Confucius and the ancient Greeks and moving up from there to—”

“Yo, Ralph,” Duncan interrupted. “Look, you want me to be impressed by your latest, deep-digging reading, and I am. But I am also concerned about a long-standing issue: Ralph the random; Ralph the visionary; speed-demon, fast-forward Ralph. You’re painting the walls of a house before you’ve laid a foundation. Ralph, designing a life worth living isn’t a lap of the Indy 500. It’s about new ways to experience time—without the stopwatch or even a clock, or calendar time and schedules, deadlines, and getting more done. But there, you’ve done it again; sucked me into the future, when what we need to do right now still has more to do with understanding what just drove you off to Italy. You want to be a moral leader, and you’re through with having people like Howard Green around who stand for something else. Well, Howard’s gone, but what’s going to keep another Howard from slipping in—or someone else on your team straying from the path?”

Ralph sighed. “So, it’s back to that,” he said. “Back to what always goes wrong.”

“Not always.” Duncan grinned.

MORAL CHALLENGES AND MEANS OF CORRECTION

We all recognize the tremendous challenge of making high-quality choices under high-stakes conditions. Many high-stakes choices have moral implications for the individuals within the organization and for the entity as a whole. The more pressured and difficult the decision, the more likely it is that the leader’s moral judgment, or lack thereof, will be tested.

Some underlying forces tend to erode the foundations of ethical and moral decision making. In the following discussion, I demonstrate how a leader can apply a systems view to his or her own organization to assess its vulnerability to the types of moral “slips” that have become commonplace in businesses (and politics) today. This can give you a stronger sense of your own moral sensitivity and the role you allow it to play as you lead.

Prevention is possible. Effective leaders can design mechanisms that help protect their organization from making decisions that lead to often unanticipated negative moral outcomes. Communicational structures that help a system function well under pressure, or that can grease an organization’s slide into corruption, can be identified and changed. Sadly, few leaders actively diagnose and correct such structures. In their own leadership models, our best future leaders will take on this central responsibility.

Feedback Loops: Protections and Perils

The central mechanism that protects an organization’s moral integrity is the feedback loop, which I introduced in Chapter Four. In any human group—from couple to corporation—feedback loops exist and carry a continuous cycle of intended messages and subjective experiences that either amplify or constrain the behaviors of every person in the group.

Feedback loops give leaders critical information about the impact of their actions on the overall system. Loops are also how the system supports or constrains the moral decisions of the leader. When a leader is acting in a morally sound manner, feedback loops that reinforce, or amplify, the behavior will ensure that an organization stays on course. When a leader makes an unwise decision, a system with carefully crafted mechanisms of constraint can rein her in. When a leader moves into territory that is morally treacherous, negative feedback loops must constrain her.

Many organizations, particularly in times of crisis, unwittingly create mechanisms that corrupt collective moral judgment and prevent individuals from challenging its perilous course. Once such dangerous feedback loops get going, they can take on a life of their own. This truth lies at the heart of many seemingly incomprehensible acts of fraud, including the amazing and tragic recent fraud of Bernie Madoff.

Madoff’s Ponzi

Outdoing even the legendary Charles Ponzi, Bernard L. Madoff is America’s most recent and spectacular fraudster. In 2009 he was convicted on charges related to defrauding investors of over $65 billion. The judge who traced his fraudulent behaviors back thirty years called them “unprecedented” and “extraordinarily evil.”1

Interestingly, Madoff’s fraud was a direct product of his personal model—his basic way of being, perceiving, and acting. (Chapter Eleven will use Ralph to describe more rigorously what I mean by personal model.) It was not a deviation from a basically upstanding life. Although it is unclear how early the fraud began, it is indisputable that it permeated his model long before his wrongdoings were brought to light.

Notoriously secretive, Madoff refused to discuss investments substantively with any of his clients. He was also highly exclusive, allowing only high-powered investors to join his fund. He may even have hidden the most basic details of his fraud from his wife and children (several of whom worked with him at the firm he had founded in the 1960s and one of whom committed suicide after Madoff’s conviction).2

How did Madoff acquire his fraudulent model? Mona Ackerman, writing for the Huffington Post, speculates that Madoff may have been a sociopath, but also offers another reason that might sound quite familiar: Madoff exhibited “all of the market’s tendencies toward greed and a lack of aversion to high risk situations.”3 In other words, he found ideas for the model all around him and simply took them to the extreme. In the end, his fraud was so brilliant and well concealed that it consumed him beyond all other awareness.

I hardly excuse Madoff’s disastrous crimes, but perhaps I can add something from a systems perspective to the explanatory mix: the self-reinforcing power of loops. Most of us know this power from personal experience. I mean the exculpatory stance we take to excuse the self for behavior we know to be “wrong.” In child development we could call it the “cookie jar” loop. If nine-year-old Jane’s small hand gets away with it once, the second time comes easier, the third time easier still as guilt fades in the face of repeated success, and a little “fraud” becomes as easy as a petty white lie. For adults with faulty character development, the cookie jar is a money-filled vault where the hand finds a means to slip in and out until, inevitably, the hand gets caught.

AN HOURGLASS OF MORAL CORRUPTORS

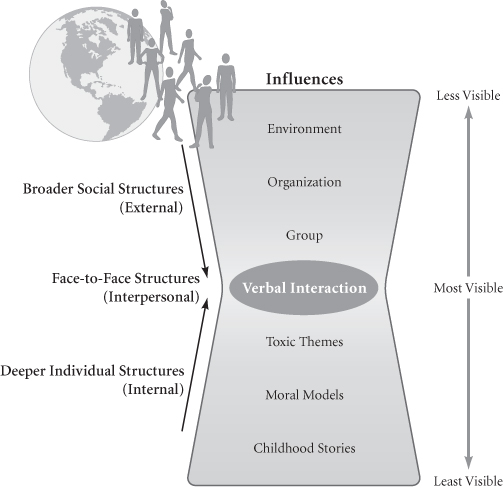

Spend a moment with Figure 10.1, which has many uses. The hourglass diagram represents influences that bear on the various interfaces in an organization. I use it in identifying morally corruptive influences or mechanisms throughout a system, at all three system levels: (1) the broader social structures, such as the business environment and the overall organization; (2) the face-to-face structures, such as group dynamics and relationships; and (3) the individual structures, including personal models and stories. Let’s look at each level’s typical mechanisms of moral corruption and consider how they might be systematically corrected. By paying attention to and correcting these mechanisms, leaders can safeguard the moral health of their organizations.

Figure 10.1 Structural Sources of Verbal Interaction

Broader Social Structures—External Events

In the broader social structure, external events take place, such as changes in economic climate. Pressures often catalyze the creation of new mechanisms within the organization: the competition has come out with something bigger, better, faster than our industry-leading product; customer needs have evolved, and our best isn’t good enough anymore; intense regulatory pressures require sweeping organizational change.

In our rapidly digitizing world, large companies seek advantage as the fastest, savviest, or most comprehensive purveyor of information on the Internet. In doing so, they cross ethical lines. For example, in digitizing the world’s books, Google Books committed hundreds of copyright infringements, eliciting a successful lawsuit by the Authors Guild.

Shareholders and boards of directors place sometimes enormous and perilous pressures on organizations and their leaders to react to outside change. Do something different! Fix the problem! As stakes rise rapidly around and within them, leaders need to beware of broadcasting feedback that can undermine their organizational system’s collective moral judgment.

Face-to-Face Structures

At the face-to-face structural level, five patterns can elicit and amplify moral corruption:

- The empowerment paradox

- Courteous compliance

- Co-opting the inner circle

- Silencing the witness

- Forgetting history

The Empowerment Paradox

The empowerment paradox is common around powerful leaders. Wanting to “empower” subordinates, but not quite trusting their capacities, these leaders assign subordinates important tasks and then, paradoxically, systemically undermine what they produce. Subordinates are thus trapped. The following are three symptoms of an empowerment paradox:

- The formal leader is known primarily as the company’s strongest performer.

- All of the organization’s key decisions are made by the formal leader.

- Significant projects require multiple “approval” meetings from which the leader sends the team back out to do more work.

In their innocent form, strong-performing leaders genuinely want their followers to succeed, but their own behavioral propensities (as strong or stuck movers, for example) get in the way. When they “step in” to show how the task “should” be done, they are opposing. But in some organizations, the leader is far from innocent, and the paradox is insidious. In these cases, a leader systematically undermines her own team as a means of hanging on to the reins of organizational power.

In either case, the result is the same. The leader’s team, once capable of employing the full range of actions, including opposes and moves, has been systematically reduced to follows and, through the process, has likely lost faith in the quality of its own actions. Thereafter, it willingly defers to an increasingly powerful leader.

Courteous Compliance

I introduced this behavioral archetype in Chapter Two. Courteous compliance occurs in “polite cultures” that ostracize or cast out opposers. The following are three symptoms of insidious courteous compliance:

- There is an absence of debate, even around critical issues.

- All of the organization’s key decisions are made by the formal leader.

- When the formal leader makes a suggestion, everyone promptly and without fail agrees.

Where courteous compliance prevails, disagreement is expressed only gently, in hushed tones, with apology. Opposers are ostracized or driven underground (creating its counterpart, covert opposition) so that the system can maintain its equilibrium. When the leader makes a move, everyone follows, making him the moral compass for the entire system. If he missteps, so will everyone else because all corrective feedback mechanisms have been silenced.

In these systems, leaders are prone to claim that they wish “someone would speak up.” However, in practice, unless the leader does something to change the system, he is in fact reinforcing it.

On the path to corruption, courteous compliance often occurs in conjunction with covert opposition. The culture over time has cemented the propensities of stuck followers who subvert their opinions to powerful leaders. Perhaps in an attempt to correct itself, the system recruits strong opposers, then systematically shuts down their feedback loops to render them silent.

Co-Opting the Inner Circle

In 1937, President Roosevelt, tired of a conservative Supreme Court that found his New Deal programs unconstitutional, proposed a bill that became known as the “court-packing” plan. Essentially, he tried to appoint additional sympathetic justices to the court in order to favor his legislative agenda. The resulting conflict largely dissipated bipartisan support for the New Deal and significantly damaged Roosevelt’s public reputation.

Co-opted inner circles are those that have been systematically disabled from seriously challenging the nominal leader. The following are three symptoms of co-opted inner circles:

- Absence of bystanding or opposition from a leader’s closest counsel

- A small group of individuals tightly and jealously holding all of the organization’s information and power

- Lack of change in the leader’s core group over a long period of time

Many organizations’ moral incorruptibility is based on well-functioning core groups whose members are chosen by nominal leaders for the diversity of perspective and voice that they bring to decision making. These inner circles of influence are not necessarily the same as those who hold top official positions; they may represent the leader’s handpicked personal counsel.

In systems that are steering off course morally, corruption can derive from the nature and deployment of power. Being included in the leader’s powerful inner circle of influence is a boon to one’s own sense of belonging, entitlement, and power—power by association or vicarious power. In exchange for these obvious benefits, followers allow themselves to be co-opted, sometimes so subtly that they don’t realize how vulnerable to corruption they have made themselves. Once they are in the inner sanctum, the risk of expulsion is terrifying.

Unless leaders include in their inner circle at least one scrappy opposer, they risk sacrificing one of their greatest assets—the pressures of moral correction. But to be most effective, this opposer must be joined by a bystander secure in her neutrality and free to present unwelcome viewpoints.

In recent American politics, the inner circle often includes a spouse. Many Americans who supported John Edwards’s presidential campaigns were as excited by the woman at his side—Elizabeth Edwards—as they were by Edwards himself. Elizabeth won the admiration of millions with her dedication to her young children, her courage in the face of debilitating cancer, and her commitment to the causes célèbres of the American left—health care reform, gay marriage, withdrawal from Iraq. Oftentimes she would campaign alone, as big a crowd-pleaser as her husband. Undoubtedly, Elizabeth was an irreplaceable fixture of Edwards’s campaigns. His Democratic nomination for vice president in 2004 and strong primary showings in 2004 and 2008 couldn’t have happened without her. Much of the Edwards appeal related to their marriage and the background and values it symbolized.

Naturally, then, when it was revealed in mid-2008 (after Edwards had suspended his presidential campaign) that the candidate had carried on an affair with his campaign videographer, Rielle Hunter, Americans poured out their sympathy for Elizabeth. These feelings gave way to shock and anger, however, when it was revealed by various sources (including campaign aide Andrew Young, in the now-infamous book The Politician) that Elizabeth not only knew of but also helped conceal her husband’s indiscretions. Once a media darling, Elizabeth Edwards was now plagued with questions of “What did she know and when did she know it?” Although she was not as pilloried as her husband (who later admitted fathering Hunter’s child), Elizabeth undoubtedly suffered a huge loss of credibility and respect with the American public as a result of the scandal.

Certainly, Elizabeth did not create her husband’s scandal, but she was implicated in it. By conducting the 2008 campaign as though nothing had happened, misleading the public as to the nature of her relationship with her husband, and risking the Democratic agenda with yet another sexual scandal (amid the Great Recession nonetheless), she defrauded the American people. Why did she eschew her own admired model—her espoused principles and values of fairness, equality, openness, and honesty—precisely when it was needed? Did she abandon it in support of the public good (perhaps truly thinking that Edwards, despite his flaws, was the best candidate to advance liberal causes) or personal benefit (the power and prestige of the White House)? Either way, she became deeply entangled, as so many spouses do. Her case exemplifies how temptations and trials permeate not only organizational inner circles but family inner circles as well.

Silencing Witnesses

Organizations and their leaders sometimes silence witnesses to limit power to a small and insular group. Symptoms of this dangerous practice include

- Ritualized excessive deference to the formal leader’s perspective and opinion

- Prevalence of negative associations with “speaking up”

- Disappearance of iconoclasts who once challenged the leader’s authority or perspectives

Silencing witnesses frequently accompanies co-optation of an inner circle. In fact, many of the mechanisms of moral corruption are mutually reinforcing and can develop a life of their own if left unchecked. Systems succeed in silencing witnesses in part by co-opting an insulated core group of insiders who, in exchange for being “in,” do not challenge the nominal leader. They also systematically target and shut down iconoclasts who refuse to be co-opted.

Witnesses are arguably the most important voices in the system. Seeking out these perspectives is often the only way to give them an audience in a system on its way toward corruption.

Forgetting History

George Orwell wrote his classic dystopian fable, Animal Farm, to warn mid-twentieth-century leftists not to ignore a historical pattern of dictatorship that is traceable back at least as far as the French Revolution of 1789. It seems that some lessons are never learned.

When John Edwards began his torrid extramarital affair and then tried to cover it up, he seemed to forget the instructive fates of President Clinton and presidential hopeful Senator Gary Hart. Both of these men torpedoed themselves politically with extramarital affairs. Losing sight of past lessons learned makes organizations and their leaders vulnerable to repeating past mistakes or inventing new ones. Symptoms of forgetting history include

- Dismissal of organizational history as irrelevant or unnecessary; absence of historical relics or myths

- Obsessive focus on the future and the opportunities it holds

- Exclusion of “old-timers” from the leader’s inner circle

Organizations and their leaders can have short memories. Failing to consider both past and present, they are capable of forgetting sordid history, both in the culture at large and within their own walls. With their sights trained on future victories, they lapse into what amounts to consensual moral blindness.

With the opening up of every new cycle of economic opportunity and promise, history suddenly seems far away and frankly irrelevant. At such times, thoughtful leaders must safeguard the lessons their organization has already learned. That doesn’t mean playing the role of historian; it means keeping a feedback loop active between the organization’s history, as retained and embodied by its elders, and the ears of its current leaders.

Individual Structures

It is easy to demonize public figures for their public moral lapses, but look back at Figure 10.1. At the individual level, structures within the behavioral profile render some leaders especially susceptible to moral corruption, but every profile carries with it moral vulnerabilities to which reflective leaders must continuously attend. By reflecting also on the mechanisms to which their behavioral profiles render them susceptible, leaders can prevent the harm those mechanisms can cause or at least minimize their effects. The following are examples of such problematic mechanisms or tendencies:

- “Not knowing”

- Unquestioning loyalty to the chief

- Reverence for power

- Not admitting error

- Absence of empathy

- Recklessness

“Not Knowing”

Cardinal Bernard Law was forced to resign as Catholic archbishop of Boston in 2002, following news that he and the Boston archdiocese had covered up child sexual abuse by priests for decades. Rather than reporting allegations of molestation to the authorities, Law had simply referred the accused priests to psychiatrists or moved them to other parishes. This awful pattern of willful blindness and purposeful cover-ups left hundreds of children victim to predatory priests and devastated Boston’s Catholic community. “I acknowledge my own responsibility for decisions which led to intense suffering. While that suffering was never intended, it could have been avoided, had I acted differently,” Law later said.4

In a more recent book explaining the collapse of the “Celtic Tiger,” Ireland’s formerly roaring economy, “[Fintan] O’Toole uses the phrase ‘unknown knowns’ to describe a cast of mind that distances itself from facts it knows to be true but ‘does not wish to process.’ ”5 In not knowing, individuals actively engage in acts that they do know to be morally wrong but whose internal “meaning” they are able to alter in order to justify their choice. The human psyche is capable of extraordinary feats. In my opinion, of all the forces that contribute to the sacrifice of moral principles, this one has no rival. On the individual level, not knowing is roughly analogous to the face-to-face-level practice of forgetting history.

Martha Stewart, the lifestyle maven whose businesses include a syndicated talk show, a magazine, and countless other media and merchandise offerings, built her $650 million fortune and empire with her talents, ruthless ambition, and a shrewd air of public wisdom.6 Talents notwithstanding, Stewart risked ruin in 2001, when her insider trading ultimately forced her to step down as chairman and CEO of her company, pay a $30,000 fine, and serve five months in federal prison.7 What led Stewart to commit fraud for relatively petty gain? Not her usual business strategy, which emphasized work as pleasure, industry, commitment to good taste, and a beloved public persona. Whatever led her astray (the whiz and whirl of Wall Street life?), her failure lay in setting aside that successful approach.

Oftentimes, after the fact, a leader who has been involved in fraud will claim he was unaware of any misdeeds. “Martha Stewart has done nothing wrong,” Stewart’s lawyers said at the time of her indictment. “She knew Sam tried to trade [the ImClone stock], but she didn’t know [my emphasis] why he was trading.”8 This excuse is frequently heard from elected officials accused of accepting bribes. Of course, this could be nothing more than willful blindness—conveniently ignoring what is obvious in order to shirk responsibility.

Leaders accustomed to adoration, praise, and success may convince themselves that what they’re doing is right, even when it isn’t. A leader who is certain she can “do no wrong” may indeed do wrong, especially if she also believes she is invincible or perfect. But I do not consider not knowing the same as denial, in either its dictionary or its psychiatric usage. In defining denial, the dictionary stresses active rebuttal; psychiatry, viewing it as a defense mechanism, stresses suppression in which a forbidden experience from the distant past is split off from conscious awareness. Thus, not knowing is not simply a “looking away” or a “turning one’s back on” or “suppressing” a terrible reality. In not knowing, individuals are fully awake to what they are doing, but are able to play a trick on their consciousness in order to feed an appetite for wealth, sex, or power. While actively performing wrongful acts, they are also actively altering the meaning and presumed consequences of these acts in their own minds in order to preserve the belief that they are morally sound.

Not knowing is the most dangerous consequence of lack of self-awareness in a leader. Setting personal alarm bells and soliciting the scrutiny of others are the greatest defenses against it. The higher the degree to which the leader has explored her own behavioral profile, the greater the tickle of concern she is likely to feel about taking morally questionable actions.

Unquestioning Loyalty to the Chief

The individual and face-to-face mechanisms that lead to moral corruption tend to complement and reinforce one another. Leaders who demand unquestioning loyalty stunt the flow of critical, and therefore corrective, information within their organizations. Circularly, an organization with many individuals who display this loyalist tendency will create a system that values such face-to-face behaviors as courteous compliance.

Devout followers tend to derive their joy and their influence by following closely on the heels of a powerful leader. Likewise, many powerful leaders choose to surround themselves with devoted fans, yes-men whose primary purpose is to confirm the leader’s authority. Deflecting critical feedback and boosting positive reinforcement, this reciprocal loop is emotionally satisfying and morally corrosive.

Rather than reward those who mindlessly obey, leaders need to unleash the voice of the opposer and actively solicit contrary opinions. Those leaders who find these tasks difficult will need to pay particular attention to this aspect of themselves as they examine and develop their leadership model (as described in the following chapters).

Reverence for Power

Power in some form—authority, hierarchy, or constraint of freedom—is inherent in social institutions, an inseparable aspect of making difficult decisions and hard choices. Individuals who tend to revere power can have difficulty opposing it and thereby lose their own power to help correct others’ morally unsound choices. Reverence for power—or ambivalence about it or fear or hatred of it—takes shape originally in our childhood stories. As a mechanism of moral corruption, revering power is closely related to unquestioning loyalty to the chief.

As leaders, individuals must understand and take responsibility for the dilemmas that their hierarchical position may create for others and attempt, within reason, to free others from the constraint this authority imposes. This means releasing others to provide timely and difficult feedback without fear of retribution.

Not Admitting Error

It is naïve to think that people “in high places” with responsibility for the well-being if not the lives of others should always open their books, their files, or their minds to debate even inside their circles or to public scrutiny on the outside. They are understandably constrained by the reality of face-to-face communication. However, some in very high places do not admit error almost as a matter of policy or, worse, as a function of character. It is these latter who concern us here inasmuch as they discourage dissent, do not invite debate, and enforce secrecy, and are unable to admit major error without being forced to do so.

The greatest danger of not admitting error is its easy descent into cover-up and lying. A drift from little lies to big ones, from little transgressions to BIG ONES, is hard to stop. When people caught in moral confusion turn their heads from one corrupt decision, they become vulnerable to turning their heads from the next and the next.

Routinely shielding error from view opens the door for the types of mental contrivances that lead to not knowing. As a leader is convincing everyone else that “he has it under control,” he may be convincing himself as well.

Absence of Empathy

When one is making difficult decisions that have an impact on others, empathy is critical to exercising good moral judgment. In its simplest sense, empathy is the ability to know the “other”—how the other feels and thinks and, in the best case, why the other acts or is likely to act as it does.

Although occurring naturally in some, empathy is as much a practice as it is a quality. In being open to the models of others and receptive to their perspectives, the leader takes a step away from a self-centered view and makes space for others to be present. Without empathy, our devotion to power can run roughshod over any moderating moral sense.

Recklessness

In Herman Melville’s enduring novel Moby-Dick, Captain Ahab launches a maniacal pursuit of the white sperm whale that bit off his leg. Ahab continues to pursue the whale, despite widespread destruction, the death of every member of his crew but Ishmael, and early good advice from first mate Starbuck, who tells the captain, “Moby-Dick seeks thee not. It is thou, thou, that madly seekest him!” Eventually, the harpoon line that Ahab plants in Moby-Dick catches Ahab as well and drags him drowning into the depths of the sea.

For landlubbers, too, recklessness can easily set off a chain of morally corrupting events that lead an entire organization astray: a leader displays a thoughtless, rash, or indiscreet sense of license, and, when he succeeds in any capacity, the success bolsters an irrational belief that he is invincible and subject only to his own rules. When these rules are seriously challenged or a crisis descends, he feels greater need to control and makes increasingly unilateral decisions. To the extent that he relies on others, he manipulates them to serving his ever-narrowing ends. Those around him trying to help are infuriated by his inability to admit error, see the sources of his behavior, or apply his own checks and balances. More and more, he simply rationalizes, not even realizing that his acts are morally indefensible.

The Enron scandal, revealed in 2001, ranks near the top of many examples of reckless leadership practices. It destroyed the organization and resulted in the loss of billions in company pensions and stockholder value. With connivance from higher up, CFO Andrew Fastow created what were called “special purpose entities” that were hidden through the use of accounting loopholes. This tactic—applied to enterprises sometimes recklessly violating the law—hid billions in debt from failed deals and projects. Fastow and other executives not only misled Enron’s board of directors and audit committee on their high-risk accounting practices but also pressured Arthur Andersen auditors to ignore the issues, thus bringing down that huge company, too.

At the root of recklessness is this leader’s infatuation with his own power. He commands our attention because he is bullish under stress. He is willing to take on the toughest problems, ones from which others who are less purposeful and driven shy away. He is fearless about confronting anyone or anything thrown in his path. Yet those same traits that have won him such acclaim will become his Achilles’ heel (his Moby-Dick) if they lead him over the edge into unjustifiable recklessness.

COMPREHENDING THE FRAUDSTER: SOME INSIGHTS INTO HOWARD GREEN

More study of Howard Green will lead us to a behavioral profile and other related dimensions that suggest a personal tendency toward fraud.

After Ralph’s return from Italy, Duncan used an hourglass drawing like Figure 10.1 to work with Ralph on how systems promote or discourage corruption. Especially at the individual level, Duncan’s guidance provided perspective on Howard Green—not only why he did what he did, nor only how Ralph might be able in the future to spot potential problems before he ever hired or promoted some similar potential leader, but also to prime Ralph’s thinking about the morally cognizant leadership model that Ralph intended to build.

Duncan took an active part in discovering as much as they could about Howard’s character and past in structural dynamic terms, including his childhood stories. One key “informant” was Howard himself, who’d let loose his own tipsy tongue at more than one prior company party. Another source of recall was Art, who had learned much about Howard in the course of past boasts and taunts that Howard had thrown at Art as a supposed rival. A third main source was Howard’s younger brother, Sam, who had been Howard’s childhood victim and witness and Howard’s only known confidant. Spouses and partners were traditionally invited to the company’s end-of-year parties. Sam, learning that Howard would not invite Vera, his “girlfriend,” saw an opportunity. He asked to come along. In an effort to help out his older brother, Sam collared Duncan, revealing much about their childhood, in addition to what Howard had already shared.

Both Howard and Sam provided clues from Howard’s preadult years. In his early years at home, he would seem to get pleasure in physically abusing Sam, his junior by three years. Parental lessons on “being kind to your brother” never had much effect.

To show their mettle in preadolescence, boys roughhouse with their peers. As a boy, Howard was an odd combination: a “nerd” who could fight hard, too hard at times, and resorted to outlawed physical tactics when fearing he would lose. It was not without reason that he was called “Who, me?” by other kids in the upper-middle-class, gated community in which he grew up.

In adolescence, Howard cultivated skills in exploitation and dirty tricks. In the elite coed boarding school he attended, most girls avoided him after a first date. A pattern that we see later in dealing with women was set early. He saw girls as sexual trophies and they “got it.” Academically, he could only be number one, endlessly fretting or resorting to tricks to assure this coveted place. One boy capable of challenging Howard’s place at the top of the class accused him of stealing and destroying a backpack containing the boy’s final research report. Other incidents fit the same pattern.

A Primordial Sexual Story and Coalition Against the Father

It is not unusual for sexual themes to be central in childhood stories of imperfect love. Many of the stories involve outright sexual abuse. Some, like Howard’s, fall short of abuse because of the way the child tells the story. Howard’s childhood story is borderline in this regard. Around age eight, what began as ordinary bullying of Sam gradually turned into an erotic windfall for Howard that was arguably the genesis of his sexual habits as an adult.

When he was caught in a particularly serious act of bullying, his mother would drag him to her bedroom, the scene of punishment, where she had him drop his pants, “the better to show your bottom, young man”; and, “so’s not to crease my skirt,” she would tuck her skirt into her panties with the stern warning, “and don’t you dare look.” Understandably, Howard took this as an invitation.

This tantalizingly naked act of shared eroticism was not the end of the performance. His mother was strikingly beautiful and loved showing it off to her “three boys” at dinner, for which she elaborately primped. It did not take Howard long to suspect that his mother followed up the spanking episodes with such primping. If the synchronicity was not conscious on his mother’s part, its routine predictability may well have made it seem so for the ever-curious (and easily aroused) Howard. At her door, with an audible sigh of pleasure, she would say, “Ah, and now dinner”—her conspiratorial signal for Howard to be ready, he thought, since the door was left just ajar enough for Howard, from his room across the hall, to see her nakedness as she dressed. When, at age ten, it became plain that what the punishment produced was not pain but an erect penis felt by both, his mother abruptly halted the practice.

His mother, who adored him—though more like a toy than a son she truly loved, more as a balm to her own narcissistic core—sucked him into a conspiracy that, for another child, would put him in an entrapping triangle and double bind. If he protects his father, he betrays his mother; if he protects his mother, he betrays his father. Unlike Martha, Howard offered no known protest about being drawn into such a trap. Far from resisting, he seemed to relish it. Is it going too far to say that he was titillated? Or was he a victim? That he freely told this and other self-condemning stories in a boastful manner says enough.

Aware of his mother’s disdain for her spouse, Howard aped her in a coalition against his father, referring to the dad as a “thin-skinned, soft-bellied, second-rate doctor, more nurse than physician.” His brother, Sam, painted an altogether different picture, saying, “Our father was a kind, deeply compassionate man,” and explaining that his income suffered because he gave all his patients the time they needed, freely referred them to colleagues he thought could serve them better than he, and, in search of an elusive diagnosis, would work late into the night without demanding greater financial return. “We were far from poor, mind you,” said Sam, “but not as rich as Mother and Howard would have it.”

Howard’s Choice of Hero

In the search for heroic models, the activity we think takes place seriously between adolescence and young adulthood, Howard dismissed his father for a different prototype close by: a rich, well-placed, ruthlessly competitive financier, his father’s college roommate and a frequent dinner guest even when their father was working late.

With perverse pride, Howard had actually revealed a belief to Art, as a young man might brag of his own “first lay,” that Howard’s first real hero, “Uncle” Frank, was also his mother’s lover. For this Howard in no part faulted her—the opposite if anything. In other matters, too, Frank became Howard’s guru in the vile ways of “winning.” The seeds of fraud had been sown.

About why Howard had told Art about this, Art thought it was meant to establish Howard’s advantage in a rivalrous war that Art had no interest in fighting. Howard had fallen into a habit of taunting Art privately with his own erotic lifestyle, in contrast to Art’s staid, “dull” relationship with Jane. Howard recollected his apprenticeship with Frank as an assurance of victory in his imaginary, one-sided war.

Sam also had insights into Howard’s choice of Frank as a hero. From Sam’s perspective, Howard had been entranced by the “uncle,” sitting at his feet and taking in all that the fundamentally corrupt man had to offer. As Sam told Duncan, “Only later did I see how debased he was, but Howard was mesmerized from the beginning. I actually heard Frank once telling Howard about the thrill he got from making a sucker of someone. They deserved it, he said. If we only knew how most philanthropists get where they are—now that would be some surprise! He’d tell us there weren’t any saints in business—just dummies who played by the rules and, here and there, men like himself who made up their own.”

At another séance, Sam had watched as Frank showed Howard his credit card scheme. Frank had five cards at the time, each with a separate bank account, not all in the States, on which he’d run up large balances and which he regarded as “play money” in more senses than one. Staying below the radar, rotating credit from one account to cover payments on another, his scheme had already worked for a long time. As Frank would say, “It’s all in the timing. You just need to know when to shut down one account and open up another.”

What turned Sam’s stomach most was how Frank had enlisted Howard in his secret liaison with their mother, getting Howard to put up the cover stories, which their father never saw through. Of the fact that Sam hadn’t managed to do anything about all that, the best he could say was, “I was just a kid too scared to cross my brother.”

Sex and Power in Howard’s Adult Life

As a fixer, Howard is energized by crises, especially when they open up opportunity to exercise power in a contest of forces he can beat down, an “enemy” he can defeat. This fixer identity adds another twist: a relationship between sex and power.

Duncan was able to construct two stories from Howard’s adulthood based on details provided by Sam. One involved Howard’s sexual relationship with a young Russian woman, a writer named Vera, about whom Howard would boast to younger, “do-gooder” Sam. The second story was but one recent example of the kind of conversation Howard would initiate with Vera, then Sam, whenever Howard was under pressure.

Vera had her own reasons for putting up with Howard. Her U.S. visa would one day run out, and she needed him to hold to his promise to help her get her green card. In truth, she settled for very little, having intimated to Sam that her sex with Howard was “not that good,” and she wondered, given that Howard was having as much additional, casual sex as he wanted, “Why me?”

She said she didn’t love Howard, largely because she knew without a doubt that he didn’t love her, despite his interrogations of what she did with whom when he was on the road or traveling. He treated her with “jealous contempt,” but out of fear and loneliness she accepted him back into bed “on call.” Prepared to compromise in order to survive, too afraid to lose him and his promise of rescue, she’d do anything he wanted; and what he wanted was always a bit of sadism framed in the form of play and playacting. His favorite sex with her was anal, her hands tied up with elastic exercise bands. In their playacting, Vera used her vulnerable persona to “bring him on.” Her masochism aroused him. He despised her, his victim mistress, and was excited by his dominance over her and others like her.

Sam speculated further about Vera’s relationship with Howard. Perhaps she’d been (and still was) attracted to him as a person of power. He was part of a world in which she needed protection from a man like that. He took pains to present himself as a man of power at his company and out in the world as the influential director of its Asia office.

Howard Under Pressure

Duncan and Ralph both wanted to know how it was that, throughout the inquiry that led to his final dismissal, Howard remained so apparently cool and unperturbed. According to Sam, in fact, Howard had been phoning Vera and him in turn. The ones to Vera could only run something like this:

VERA: (Picking up) Hello?

HOWARD: Vera? Good. I need a fix.

VERA: Hi, Howard. Right now isn’t—

HOWARD: You didn’t listen. I said “I need a fix.” Big doings in Asia. Big! They’re sniffing around. That f—g Martha. Asia is my territory. Mine. If those bastards catch on to my stuff, little lady—I have to be on a plane at dawn.

VERA: But Howard—

HOWARD: No “buts” except your pretty white round one. I’m late for a call with TJ. You’ll see me as soon as it’s over. Be ready. (Hangs up)

Immediately thereafter, Howard would call Sam:

HOWARD: Just cluing you in on something big. My baby, the Asia office, is under siege. I’ll be on my way there tomorrow a.m. We’ll see whether TJ’s firewall holds up. They’ve sent their big guns, Ian and Duncan, so it’s up to me again. You know my future hangs on this. My little Russki’s standing by. I can’t wait to get in the saddle. Ride hard—you know what I mean?

SAM: So orgy then war.

HOWARD: Kiddo, if the truth be told, for me they’re one and the same.

SAM: Look, is that why you called?

HOWARD: Hey, you’re my kid brother—“counselor”—remember? You know: “connection,” that’s what you always want, so I’m connecting.

SAM: Oh, Howie, when you picture all this in your mind, do you actually get hard?

HOWARD: No. Well, yes, but that’s because I’m just about to see my—

SAM: Just call Vera, okay?

HOWARD: Hey, little man—

SAM: Please, Howard, let me go. Call when you get back so we can have a decent conversation. (Hangs up)

Howard as a Specimen Candidate for Fraud

I’m spending so many words on Howard because there is much to learn from him. Although he is a fictional character in my ClearFacts tale—the one most likely to tempt his fate in fraud—I assure you again that he has strong basis in history and fact. I created him from two main sources: articles, memoirs, and biographies from the public domain; and behind-the-scenes personal information to which only therapists and clinical consultants are regularly privy. I’ve done both of these jobs for decades, and, believe me, those experiences guided me in creating the character of Howard. From him let me distill for you now an informed portrait of likely candidates for committing fraud. I’ll discuss the ten dimensions summarized in the following list.

Ten Dimensions Tending Toward Fraud

1. Behavioral Profile—Only a Warning Sign

In low stakes, Howard is a mover in closed power, the core profile of many leaders who commit fraud, be it financial or sexual or both. However, I can’t say often enough that profiles in low stakes tell little unless one steps back and assesses how the person’s “up” and “down” sides compare, and how his behavior changes in high-stakes situations, including his dark sides and shadow. Howard’s high-stakes behavior must be compared in two contexts. In his distant Asia office, his closed-power profile transmuted as one might expect, into the prosecutor and fixer modes, and was concentrated in the dark sides of both spectrums (as demonstrated by his tastes in sexual entertainment and by his underlings, terrorized into silence). Howard’s duplicity, his behaving one way at home in the presence of authority and another in Asia when he was in charge, is a reminder that the profile of mover in closed power is only a warning that calls for alertness to behavior across contexts.

2. Choice of Hero

If Howard were one to scan culture and history for his choice of a hero (see Chapter Nine), figures like General Patton would be a logical selection. Rudolph Giuliani and Elliot Spitzer would be more current heroes Howard would model himself after. As it turns out, Howard chose someone closer by. He had no real contact with his cuckolded father, but he identified with Uncle Frank, a crassly boastful moral blackguard, a mentor in the erotic delights of “winning.”

3. Proneness to Insidious Forms of Courteous Compliance

Howard’s proneness to courteous compliance had unusual origins. Usually, courteous compliance comes from people who are afraid to speak up to a controlling or tyrannical figure in a position of power; it is typically a risk-aversive take on fearing to “speak truth to power.” That was not the case with Howard. Ralph was a leader who, far from penalizing those who spoke truths difficult to hear, welcomed them. Howard’s motive in not coming clean was more sinister. He, with TJ’s help, was investing recklessly in order to prove himself a “winner,” and when his judgments backfired, he turned to TJ to cover up their failures. Had he not failed, had he succeeded, not only would there be more reason for his bonuses and promotions, he would do Uncle Frank proud. In Howard’s mind, courteous compliance was part of the game’s excitement.

4. Absence of Empathy and a Denial of Having a Shadow

In Chapter Eleven, I will introduce an assessment instrument that measures and reports an individual’s behavioral profile and its propensities. Experienced consultants like Duncan, familiar with structural dynamics, are able to make broad but fairly accurate judgments or assessments of how such an individual would score on this instrument from behavior observed in the room. Howard, Duncan would predict, would score low or near zero in the affect domain.

Howard’s childhood stories are devoid of empathy. He had little for his brother or his father, or, incidentally, for his mother in her dying days and hours. He had no appetite for introspection, one of the best forms of constraint on moral excess. It is even possible that asking him to reflect on his dark sides and shadow might draw a blank.

I have made much of leaders’ capacity and willingness to acknowledge and take responsibility for their shadow. Denial of the shadow both follows and is an extension of lack of empathy. If, on top of having neither empathy nor compassion for those damaged by our shadow, we deny we have one, we thereby remove virtually all hope of correction or redemption. In this respect, oddly, Howard comes closest as a fraudster to Bernie Madoff. Madoff snookered the SEC for years in what amounts to an attitude of courteous compliance. Publicly, he expressed no genuine empathy for his victims’ lost fortunes and broken lives, and his son’s death suggests the stain he left on the lives of people closest to him.

5. Narcissism

In public confession, John Edwards admitted to being narcissistic. Howard, at least as narcissistic as Edwards, would confess to no wrongdoing, and it seems safe to say that he would not have admitted to narcissism, either. Some people embedded in power simply do not have the word in their vocabulary.

6. Evidence of Moral Compromise

Howard’s record of moral compromise originates in his early history, as documented in his stories, which entailed sexual exploitation (“seeing girls as sexual trophies”) and damage to competitors (his unfair fighting and a willingness to go to extreme lengths to be number one in his class). When moral compromise takes root in early character development, the fraudulence loop mentioned earlier takes on new meaning in adulthood. For Howard, conscious moral concern put up little resistance.

In the modern world of work, it is difficult if not impossible for any leader to hide the nature of his moral compass. Even if, as in Howard’s case, an effort is made to hide it from superiors, those directly affected by his decisions and ways of leading will make their own informed judgment; eventually they will call him out. Thus Howard was unmasked by a cautionary e-mail.

7. Not Knowing and Admitting No Error

Earlier in the chapter I acknowledged the moral ambiguity of some acts of not knowing. It isn’t always possible to be certain the extent to which not knowing plays a part in fraud or how deliberately it enters into a fraudster’s regular way of doing things. Some of the accused pedophile priests, though in fact guilty, were otherwise “good” people. Only in this sense was Howard a “good” person. He had high personal standards for achievement, pouring himself into tasks in search of perfection. These attributes can mislead those responsible for rewarding up-and-coming leaders like Howard, for behind this drive there was a need to succeed that bordered on the ruthless.

That he refused to admit any complicity, even when it was determined that he could not be proven guilty, does not bode well for his future either. Moral integrity is not his middle name. The boy who cried “Who, me?” lives on. Howard is not unique on this score. The band of CEOs and company officials who stood before Congress in January 2010 for questioning about their roles in the financial debacle of 2008 (Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs, James Dimon of JPMorgan Chase, John Mack of Morgan Stanley, and Brian Moynihan of Bank of America), and those CEOs implicated in the disastrous Gulf oil spill (BP’s Tony Hayward most notably) were no more forthcoming than Howard. Perhaps that is why many Americans reacted so sympathetically to the late former secretary of defense Robert McNamara’s admission of error related to policies surrounding the American war in Vietnam.

Coupling not admitting error with unquestioning loyalty to the chief can create a powerful, odd moral logic that pulls a person toward voluntary silence. But in Howard’s case it is safe to say that his not admitting error was, if anything, driven more by loyalty to Uncle Frank than loyalty to the chief.

8. Silencing the Witnesses

At this, Howard did his best but failed. While he was free and ahead in his game in Asia, he used all available devices to clip the tongues of those he “led,” developing a culture of fear, intimidating anyone who spoke up, firing those who tried. All this Duncan had learned during his night out with Howard’s inebriated assistant, and later confirmed with others after the fraud was discovered. But before Asia—openly oppose? actively bystand? Howard didn’t try them; he saw them as mistakes. During Asia, except for the early, end-run e-mail of unknown authorship about the fraud, he kept a tight inner circle, a party of two like-minded conspirators who we suspect eroticized the game of “beating the system.”

9. Excessive Ambition and Aggressive Striving for Competitive Advantage

Howard made no effort to hide his ambition; he put it on display, at times with operatic grandiosity, and, as with many before him with similar behavioral profiles, he was rewarded for that display. The warning signs here are not so much the ambitions themselves nor his goals of achieving wealth, status, and power. The real tip-offs concerned his means for achieving these goals, his unsavory attitudes toward women and sex, and his unfortunate moral premise that winning is proof of having done “right.”

Howard took pride not in work itself but in how work could serve his ambition to rise as quickly as possible to a position of real official power. He did good work, earning rapid promotion to director of sales.

10. Weak Intimate Ties

Where there is no home for empathy, intimate relationships are homeless too. Howard had few close ties beyond his brother, Sam, from whom he took but gave back nothing of quality in quick teaser phone calls that flaunted his sexual or warrior prowess. He had one friend whom he’d not seen in years, but only Vera showed up on his dance card, and his relationship with her was exploitative, at best. Oh, he had many business contacts, but knew no one capable of calling him out on wrongful acts out of concern or love. His hidden, nefarious partnership in fraud with Template Jones cannot possibly count here as an intimate relationship.

You know by now how much weight I place on intimate ties; indeed, they are the heaviest counterweight and external check on any candidate’s vulnerability to fraud, if intimates are able and willing to bystand and oppose in the service of a shared moral purpose. Jane provided this service for Art, as Sonia did for Ralph in high style. Neither of these men, I venture, would be likely candidates for fraud, sexual or financial.

THE LITTLE WE KNOW

We need to learn more about how to understand and assess the development of moral character in leaders and potential leaders.

- What clues might ignoble morals-shaping stories like Howard’s offer?

- Can morally exalting stories, once elicited, be relied on to hold firm under pressure or temptation?

- Is it possible to assess a leader’s moral character before he does damage to himself and those around him?

- Can an organization build into its culture practices that attenuate individual tendencies to succumb to egregious moral lapses?

- Is immunization from the fraud virus possible?

- What role does an organization’s incentive system play?

GOOD MODELS THAT GO BAD

At this stage in his career, from all we know about him, Howard does not have an even indirectly expressed leadership model, and certainly not a “good” one. Most good models rest on a sound moral foundation. Chapters Eleven and Twelve will argue that a leader who builds his model seriously and systematically will be a better leader. Before going there, it must be said that a proven good model can go morally wrong if one absolute requirement of model building, responding to a legitimate constraint, has been ignored. A legitimate constraint is a properly delivered challenge to some aspect of one’s model.

The example of Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Federal Reserve for eighteen years, is particularly useful here because a chink in his model, a dismissal of a legitimate constraint, had serious moral consequences with direct links to fraud. Here, briefly, is the relevant part of his story, that of a “great” leader’s fall due to a flawed moral decision. In Chapter Twelve, we look at Greenspan’s model itself.

Alan Greenspan tells of his assiduously built economic model in his charmingly candid memoir The Age of Turbulence. In a word, free-market capitalism without regulation lay at its core. Throughout Greenspan’s long service, his model helped the market survive down cycles and spawned a period of continuous growth. A PBS Frontline documentary, The Warning, picks up on his story. It depicts a models clash between Greenspan and Brooksley Born, a securities law enforcer appointed to an obscure bureaucratic agency charged with monitoring arcane instruments known as derivatives, or “swaps,” by Wall Street because only the parties in the transaction knew what was happening. The only detailed records had been buried in the filing cabinets of the immediate players. In them, Born saw recklessness and a probability of fraud. When Born confronted Greenspan, she was flummoxed by his model’s dedication to deregulation. “Even when there is fraud?” she is reported to have asked. “Yes, even fraud,” he is said to have answered.

When Born refused to back off, the documentary continues, Greenspan set his notable disciples (Robert Rubin and Larry Summers in particular) on her like guard dogs in what was judged intimidation calculated to silence the witness. And when she still wouldn’t back down, she faced them and a one-sided congressional committee, which stripped Born’s agency of its powers. Not long afterward, she resigned.

SUMMING UP AT CLEARFACTS

I began this chapter with interactions between Ralph and Sonia Waterman leading up to Ralph’s resolve to make morality a central part of his leadership model and his recognition that the same concern about moral rightness must inform the models for living he and Sonia would work on together.

Ultimately, Ralph and his team recognized that only a multicausal account can make sense of failures in moral behavior. The larger environment is implicated. Wall Street is implicated along with Congress. The immediate organizational context is implicated and so are an organization’s leaders, individually and as a group. But the team was willing to pledge to do whatever was called for to insure itself against a repeat of the Howard-TJ misadventure. For example, ClearFacts would support external regulation of the financial industry, which seems to many to foster the culture of greed that morally vulnerable organizations and leader types buy into. But will these steps be enough? No. External controls are not the best and only source of control. Unless individual leaders, in whose hands final responsibility rests, act consistently and forcefully, external controls are unlikely to stem the tide.

In Chapters Eleven and Twelve we move on to Ralph’s experience creating his own models, partly in collaboration with his wife, and extending resources to his team so that they can work on useful models for themselves.

- Unquestioning loyalty to the chief

- Silencing the witnesses

- Co-opting the inner circle

- Insidious forms of courteous compliance

- Forgetting history

- Not knowing

- Reverence for power

- Is there such a thing as moral intelligence?

- How would you define it?

- As a leader, how would you help those you lead develop and build on it?

Notes

1. U.S. Attorney, Southern District of New York. “Bernard L. Madoff Pleads Guilty to Eleven-Count Criminal Information and Is Remanded into Custody” [Press release], Mar. 12, 2009. www.usdoj.gov/usao/nys/press releases/March09/madoffbernardpleapr.pdf; Frank, R. “Madoff Jailed After Admitting Epic Scam.” Wall Street Journal, Mar. 13, 2009. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123685693449906551.html?mod=djemalertNEWS; Zambito, T. “Bye Bye Bernie: Ponzi King Madoff Sentenced to 150 Years.” New York Daily News, June 29, 2009. www.nydailynews.com/money/2009/06/29/2009–06–29_madoff_gets_max.html; Tse, T. M. “Madoff Sentenced to 150 Years.” Washington Post, June 30, 2009. www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/06/29/AR2009062902015.html.

2. “The Madoff Case: A Timeline,” Mar. 12, 2009. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB112966954231272304.html?.

3. Ackerman, M. “The Psychology Behind Bernie Madoff.” Huffington Post, Dec. 18, 2008. www.huffingtonpost.com/mona-ackerman/the-psychology-behind-ber_b_151966.html.

4. Paulson, M. “Cardinal Begs Abuse Victims’ Forgiveness.” Boston Globe, Nov. 4, 2002, p. A1.

5. Jack, I. “Ireland: The Rise and the Crash.” New York Review of Books, Nov. 11, 2010, 57(17). www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2010/nov/11/ireland-rise-crash/.

6. Goldman, L., and Blakeley, K. “The 20 Richest Women in Entertainment.” Forbes.com, Jan. 17, 2007. www.forbes.com/2007/01/17/richest-women-entertainment-tech-media-cz_lg_richwomen07_0118womenstars_lander.html.

7. “Stewart Sentenced to Five Months in Prison.” Reuters, July 17, 2004. www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/07/17/1089694573700.html.

8. Scannell, K., and Cohen, L. P. “Martha Stewart Pleads Not Guilty to Charges.” Wall Street Journal Online, June 5, 2003. http://online.wsj.com/article/0,SB105473045227104600,00.html.