chapter SEVEN

Narrative Purpose

In Chapter Six, I emphasized the importance of story in personal life. This chapter carries story to interpersonal and organizational levels. Doing this will prepare the way for our understanding some of CEO Ralph’s perceptions and behavior when we move to high-stakes moments at ClearFacts. As individuals create, perpetuate, and alter their own essential unifying personal stories, in their ongoing social interactions they also weave the stories of others and of organizations in with their own. Recall that at the synthesized core of a person’s stories lies the person’s identity. So, too, shared stories are essential to forming and perpetuating the identity of a group.

For example, a married couple’s unifying identity as a couple is based on the stories the pair accepts about how they each chose to enter the marriage, what commitments they worked out over the years, and what purpose their closeness continues to serve. Each partner might have his or her own way of telling and applying that story, but their versions share much common ground. The same applies to business partnerships, friendships, families, and other stable relationships, and continues to apply on up to larger organizations and institutions of which people feel they are part. In this chapter, our main interest lies at the team and corporate levels, but I will also go beyond that to, for example, a people’s identity as a nation. National narrative purpose is defined and challenged in exciting times like ours.

In the workplace, at every level, one job of a leader is to articulate and defend the story that keeps the organization together and promotes its general success. Another job is to make sure that the story stays close to the truth. I refer to such a story maintained by a leader as an organization’s narrative purpose. Narrative purpose is a group’s or organization’s reasons for being, particularly as understood and maintained by its leaders. It is a coherent articulation of what an organization “does”—its goals and relevant activities. Narrative purpose generally includes some conception of how the organization arose and what brings it to the current moment, in support of the narrative, not for the sake of chronology.

Like personal stories, a narrative purpose may be tinged with shadow in various quarters of any group as a whole. For a corporate leader like Ralph, the challenge is to keep the story of narrative purpose both bright and true enough to keep all groups in the organization directed, healthy, and productive.

Just as individuals gain by understanding their personal stories and seeing how those stories shape their behaviors, so a group of any size can strengthen its identity and gain in other ways by sharing a story and knowing what that unifying story is. By redirecting conversation to the level of narrative purpose, a stuck group can sometimes raise itself out of impasse and cycles of escalation to find commonalities and constructive links.

Learning about narrative purpose prepares you to understand the narrative challenge to Ralph and his leadership team when relationships at ClearFacts degenerate under high-stakes pressures. It will also prepare you to see what Ralph and Sonia Waterman can gain by handling, as a couple, the pressures of Ralph’s working life.

ASPECTS OF NARRATIVE PURPOSE

In considering narrative purpose, it is useful to focus on how clear the purpose actually is, its social and moral dimension, ways in which the narrative can be shared, and the group’s underlying model of practice.

Clarity of Purpose

The purpose ought to be clear. For example, Apple, named number one on Fortune magazine’s 2010 list of the world’s most admired companies, has maintained a clear narrative purpose: innovation. It is a “company that changed the way we do everything from buy music to design products to engage with the world around us,” the magazine’s Christopher Tkaczyk notes.1

At any point in time, an organization’s leaders should be able to tell a story of where their organization has been, where it is at the time of telling, where it is heading (that is, its destination), and why it wants to reach this destination. In other words: Why was the organization started? What is it doing now? What will it do in the future? And what is the purpose of all of this? Like the plot of a good work of fiction, an organization’s narrative purpose should be compelling—justifying the continued telling of its story, the organization’s continuation. As Collins and Porras write in Built to Last, a good narrative purpose answers the question, “Why not just shut this organization down, cash out, and sell off the assets?”2

A Moral, Social Dimension

Among an organization’s important reasons for being are what it wants to contribute to the world and how it wants to change the world into a better place—in other words, its social and moral purpose. To be effective, an organization’s narrative purpose cannot be simply amassing profit or accruing power. Organizations need to be perceived as relevant and successful, and that requires a social and moral dimension.

How to define moral purpose? In The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, historian Niall Ferguson says willingness to sacrifice money or profit is evidence of moral purpose.3 Fundamentally I agree with this definition, although money is not the only possible “material” sacrifice. For example, legend has it that when President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he whispered to an aide, “We have lost the South for a generation.” LBJ was well aware that his party’s support of civil rights for blacks would cost them thousands of votes.4

Of course, money can be sacrificed. In one of the most lauded handlings of a corporate crisis in history, Johnson & Johnson (J&J) in 1982, in response to a series of cyanide poisonings of Extra Strength Tylenol that killed seven people on Chicago’s West Side, launched a major offensive. Its top executives decided to put customer safety ahead of profits and other financial concerns, and alerted customers across the nation, via the media, not to consume any type of Tylenol product. Along with stopping the production and advertising of Tylenol, J&J recalled all Tylenol capsules from the market. The recall included approximately thirty-one million bottles of Tylenol, at a retail value of more than $100 million. But the immediate sacrifice in cash also yielded some substantial long-term material return: thanks to the vision and responsibility—the moral purpose—of its leadership, J&J maintained a valuable part of its narrative purpose: its reputation for integrity and commitment to alleviating pain and suffering.

As J&J’s example suggests, in order for an organization to serve a moral purpose, it must have moral leadership. An organization’s narrative purpose must be carried out by leaders with moral character, whose individual or collective inclinations are to preserve a moral dimension of purpose. Not all firms have such leaders. In The Rise and Fall of Bear Stearns, Alan C. Greenberg, former chief executive of Bear Stearns, writes that his successor, James Cayne, led Bear Stearns during the time it “expanded recklessly into subprime mortgages and lost any semblance of a serious risk-management function,”5 all, ostensibly, in the name of higher profits. Thus, Bear Stearns’s reputation for risk management disappeared, and so did the firm itself; Cayne’s failure of moral leadership lay in hiding risk from investors, losing sight of and damaging the firm’s previous narrative purpose.

A Shareable Big Picture

Collectively, an organization’s leadership must understand its narrative purpose. Although members of the leadership might have different day-to-day tasks and agendas—managing finances, developing products, handling legal issues, or tackling public relations, for example—they should all have a clear and consistent idea of the “big picture.” They should be able to communicate this narrative purpose to the rank and file of the organization and to the general public (consumers, potential clients, and so on). In order to do this, an organization must have its own, often particular or unique language in which its key members are fluent.

Communicating narrative purpose to the rank and file of an organization—the secretaries; midlevel management; the workers answering the phones, tightening the bolts, filing the paperwork—is essential to an organization’s success and the mark of a good leader. Not just the leaders of an organization but all its members must have a sense of purpose—an understanding that what they do is important and serves the organization’s larger narrative purpose. In the best-selling Leadership Is an Art, Max De Pree discusses the importance of giving employees meaningful work—a strategy that De Pree practiced during his tenure as chairman and CEO of furniture maker Herman Miller.6 The company’s success must have been part of the reason that Fortune magazine has regularly named Herman Miller one of America’s “best managed” and “most innovative,” as well as one of the best to work for.

An Underlying Practice Model

Both in the telling and doing of “what it does,” an organization should also rely on a model—a necessarily complex representation of how the organization works—in order to achieve its narrative purpose. This practice model, a studiously constructed set of guidelines (principles, steps, and practices) for reaching goals, should remain accessible on demand, in order to be ready for mindful change and adjustments as the organization evolves. Among other things, the model allows an organization’s leaders to see its unified view. Lack of such a working model was a clear issue at Lehman Brothers, where betrayals and infighting among its leaders—the so-called Ponderosa Boys—brought down the firm and left it unable to cope when disaster struck.7 Later in this chapter, I will discuss the idea of a practice model as it applies to our ClearFacts team.

When an organization commits to a narrative purpose, it provides itself an opportunity to serve a cause greater than its own self-interest, which becomes the means for its own success and for meaningful, purpose-driven lives for its employees. People who find broader narrative purposes to which they can commit, in their business or their personal lives, feel uplift, purpose, hope, and direction.

PRESENCE OR ABSENCE OF NARRATIVE PURPOSE

Thomas J. Watson Jr., former chief executive of IBM, summed up his view of corporate beliefs: “I firmly believe that any organization, in order to survive and achieve success, must have a sound set of beliefs on which it premises all its policies and actions. … [T]he most important single factor in corporate success is faithful adherence to those beliefs. … Beliefs must always come before policies, practices, and goals. The latter must always be altered if they are seen to violate fundamental beliefs.”8

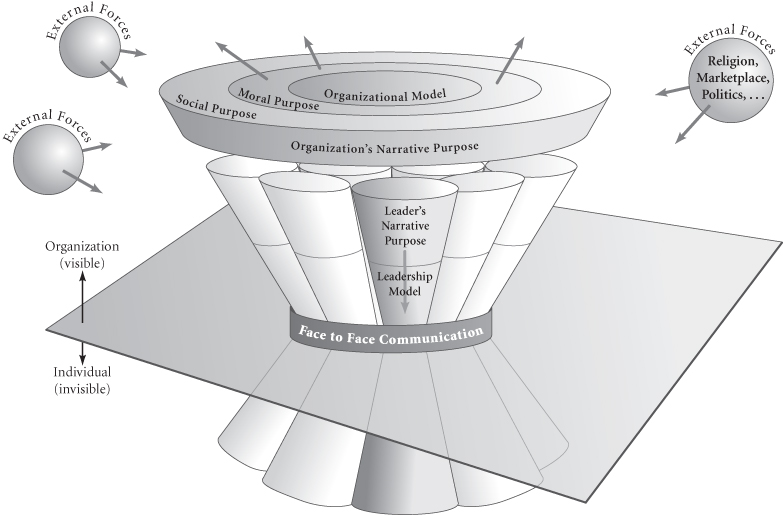

Of course every large organization’s narrative purpose will differ from those of other organizations, but at its best, any organization and its narrative purpose might be represented by Figure 7.1. The multiple vertical columns suggest that the organizational narrative purpose needs the support of its various leaders. In turn, individual leaders need support and direction in the form of their own narrative purpose and their own individual model of leadership. While reviewing the figure, consider potential obstacles to sustaining narrative purpose that come from within and from without.

Figure 7.1 Narrative Purpose Intact

Obstacles Without

Figure 7.1 includes forces outside the organization itself—in other words, the world we live in, with its many imperfections. These I refer to as external forces—such as outside social organizations, the marketplace, or politics. In that world, ideals are likely (or perhaps destined) to break down. This is one kind of obstacle to narrative purpose. Let me provide three examples:

- Planned Parenthood, whose narrative purpose undoubtedly involves securing for women various legal rights related to family planning, often encounters both political and religious opposition. Such opposition might occur at the ballot box or in pushback from such organizations as the National Right to Life Committee or the Catholic Church—whose own narrative purposes are at odds with that of Planned Parenthood.

- The Obama administration, in handling the Great Recession of 2008 and the Mideast uprisings in 2010–11, needed to weigh U.S. policies against the interests of other governments in achieving its narrative purpose.

- Google, whose narrative purpose might (more or less currently) be summed up as “making all the world’s information available with a simple Web search,” must deal with countless lawsuits, uncooperative or censorious governments (such as China’s), and corporate rivals in fulfilling its narrative purpose.

Obstacles Within

Imperfections within an organization can also compromise its narrative purpose. One possible flaw might be that an organization doesn’t have a strong narrative purpose or reason for being in the first place. More likely, its leaders don’t understand the reason or strongly disagree on parts of it.

In the ClearFacts leadership team, for example, Ian finds meaning in ClearFacts’s narrative purpose, but emphasizes bottom-line policies as a means for getting there. Howard’s commitment to ClearFacts’s narrative purpose is questionable. His personal goals—power and wealth—basically supersede what ClearFacts is trying to do in the world.

Often when organizations go through a period of change—such as a change in leadership—they lose sight of their narrative purpose or fail to modify and align it with a change in direction. One of the reasons many experts recommend that new leadership rise through the ranks, rather than be imported from outside the organization, is to sustain a company’s purpose and moral foundations.

If a company’s big story lacks key components (a practice model and moral purpose), its identity suffers, impairing its ability to achieve a fulfilling narrative purpose. This happens when leaders lose track of a company’s big story, as happened at Bear Stearns. As I suggested in my earlier reference to Niall Ferguson’s book, a narrative purpose without a social or moral dimension—thoughts beyond profit and material success—is unlikely to work in the first place.

Another possibility is that an organization has a coherent articulation of what it “does,” but disallows competing models held by its leadership. For this reason, each organization must have internal mechanisms in place to reconcile differences between members of the leadership or to take advantage of these differences. For example, a company that provides medical care may have one leader focused on profits, another on innovation, and another on serving people. These goals are not necessarily mutually exclusive; however, they can be if not handled properly. In 2010, fighting in President Obama’s inner circle over the Afghanistan war was made quite public, crippling its narrative purpose (which, in this case, was to present a united front against U.S. adversaries).9

Yet another problem might be that the organization lacks a “language,” or its key members lack fluency in this language. Structural dynamics views failure in communication essentially as a failure of language. The breakdowns in communication it describes among members of a leadership team can be fatal to an organization’s narrative purpose. Leaders must be able to communicate effectively with others with different views and profiles, especially in terms of power, affect, and meaning. If an organization does not have a model—a set of principles, steps, and practices—to deal with such language issues, or if its leaders do not have a dynamically unified view of the model, the organization will lack the diversity that must anchor unity of purpose.

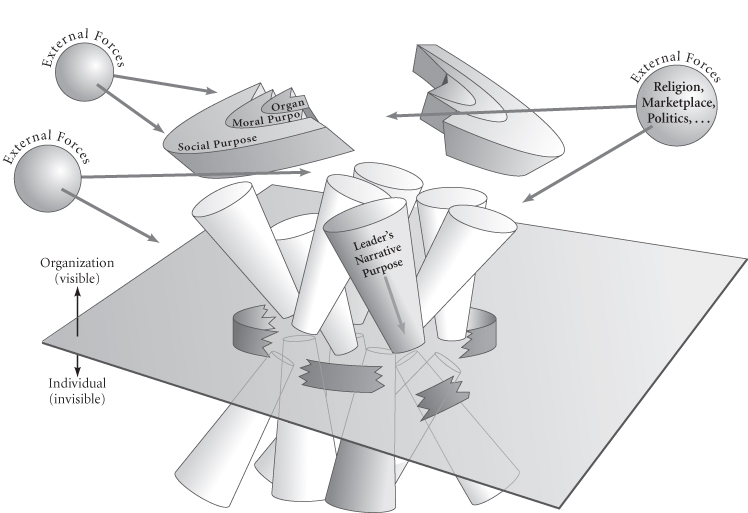

Figure 7.2 illustrates how external forces and obstacles within can derail a narrative purpose.

Figure 7.2 Narrative Purpose Broken

Arthur Andersen: Rise and Fall with Change of Leadership

Not so long ago, the accounting firm Arthur Andersen LLP, cofounded in 1913 by Arthur Andersen, a former professor, was a legendary, ideal organization. In Executive Wisdom, Richard Kilburg notes that the historical cornerstones of Andersen’s business were “to provide good client service, produce quality audits, manage staff well, and produce profits.”10 This strong narrative purpose, Kilburg writes, “rapidly earned [the firm] a reputation for both competence and ethical behavior.”11 Most important here was that profit was not the be-all and end-all of Arthur Andersen. As a result of this brand of ethics, Andersen’s company over the years became phenomenally successful and earned a “hard-won and generations-old reputation for professional integrity.”12 This reputation continued to serve it well even after Andersen’s death in 1947; and Andersen’s successor, Leonard Spacek, maintained its successes and growth.

However, after Andersen’s death, the company began to expand its portfolio, thus transforming the company’s narrative purpose based on its success in accounting, and by the mid-1980s, the company’s consulting division, which had become far more profitable than its accounting services, split off to form its own company (eventually named Accenture) in 2000. This was a significant blow to the mother company, which had come to rely on its consulting practice for most of its profits. Joe Berardino, selected by over 90 percent of AA’s seventeen hundred partners to head the firm, had gained a reputation for integrity and competence after implementing an agreement that required financial disclosure, but in an attempt to keep the firm’s profits high, Berardino, despite his charge, continued to approve types of transactions that “its founder probably never would have authorized.”13 The reason was clear: money. Accounting disasters were eventually exposed, and led to over $300 billion in losses to investors, as well as a national outcry in late 2001 and early 2002. As a result of this scandal—and the inextricably linked loss of narrative purpose—Berardino lost his job, and Arthur Andersen surrendered its licenses to practice as Certified Public Accountants in the United States. Today, the once-great firm founded by the good professor still exists but only nominally—little more than a bad memory in the history of American business.

HOW TO BUILD AND SECURE A NARRATIVE PURPOSE

The Arthur Andersen story demonstrates that a strong narrative purpose is essential to a company’s survival. I have already described four criteria to consider when creating or evaluating an ongoing narrative purpose:

How to further ensure that your company acquires and maintains its narrative purpose? The primary keeper of a company’s narrative purpose must be its executive leader. In line with this, as Coca-Cola CEO Muhtar Kent says, “There are two things … a CEO can never delegate. … The first is communicating your organization’s vision for the future, and the second is ensuring that you are developing the right leaders to execute that vision. Everything about a company’s reputation emanates from those two sources of influence.”14

In times of crisis, a top leader’s choices do not necessarily follow straight-line logic, but the goal—finding the right voices to articulate and carry his or her narrative forward—remains the same.

RALPH’S AND CLEARFACTS’S NARRATIVE PURPOSE

Well before coming to ClearFacts, but particularly after Al Gore brought the need for carbon-free fuel to popular attention, Ralph had been on a personal campaign to do something real about the “global energy crisis” and the need for a new national grid. “This is not political or ideological or even ecological alone. It is a matter of survival,” he insisted.

Ralph had been in his third year as CEO in a company that, he concluded, profited from the energy status quo and had no interest in adding energy-saving features to the design of new facilities it was planning to build. His entreaties to his board to change direction fell on deaf ears. Around that time, he attended “Davos”—the World Economic Forum, an annual meeting of global political and business elites held in Davos, Switzerland—where he got the welcome ear of a member of the ClearFacts board.

At that moment, ClearFacts was in economic doldrums and desperate to put fresh wind in its sails. “As chairman,” Ralph’s new fan told Ralph at the end of the hiring process, “I had to twist a few arms, but I prevailed.” High on the search firm’s list of assessment criteria for a new CEO was that he or she “tell a good story.” And Ralph was customarily forthright in his make-or-break, hire-me-or-not attitude when he finally met with ClearFacts’s board. The next section is a brief account of what he said, including answers to some well-put questions. Although the rhetoric includes such terms as mission, vision, plan, and strategy, I will nudge Ralph’s language toward our more layered terms, such as narrative purpose, model, team diversity, and social purpose, some of which were close to the words he used.

Ralph summed up his narrative purpose thus. (In it you will see mention of some of the stipulations he laid down when he was hired, as described in Chapter One):

The last is easier to do as a student, as Christensen himself was when he wrote the article, but harder when ensconced in the business world and subject to its pressures. However, if a firm’s top leaders lack individual commitment to their firm’s larger cause, or if their personal goals and models can’t be reconciled with the firm’s, both larger purpose and model will be at risk.

Ralph had gotten all he’d asked for: a new director of HR, with whom he’d worked before; a coach to help him and his team build their models; and an autonomous strategy investment team he would lead.

When he got his feet on the ground, Ralph felt that the management team he had inherited, plus Martha, functioned relatively well with the usual interpersonal glitches. Still, there were model clashes, which Duncan assured him he would learn how to manage. Duncan opined that these clashes were allowed, if not encouraged, by the open system Ralph sponsored, and that learning from them was far better than driving them underground.

The team’s commitment to narrative purpose was another matter. Ralph discovered that individual team members’ commitment to his and now the firm’s larger purpose varied. Martha and Art were enthusiastic. Clearly, they were distracted by issues at work and home, but were committed nonetheless. Ian, admitting that he was a skeptic about the science of global warming, voiced an interest in principle; for now, his concern was more on the cost than the science. Ralph sensed correctly that Howard viewed the new company emphasis as a career opportunity. Officially, he’d been given a director role in Office Asia with powers he would stretch beyond investment suggestions that had to be approved by Ian, Ralph, and the team, in that order. At this low-stakes stage, despite minor cracks, the team’s purpose, model, and moral compass were more or less solidly in place.

In time, Ralph grew restive. Tired, over-driven, pressed to spend more time at home, but probably wanting more passionate commitment from his team on its green energy cause, he committed an impulsive act in bringing Ron aboard. Although this threw the team into temporary turmoil, they settled down, the foundations of their purpose and model pretty much in place.

The next chapter takes us beyond that point, to where Ralph and members of his team found themselves on high-stakes turf.

- What is or should be the moral purpose associated with each?

- Note gaps between the espoused and displayed narratives.

- What is the relationship between your personal narrative and moral purpose and those of the other two organizations?

- Is my organization on its avowed narrative track?

- What, if anything, am I doing to steer it off its true path?

- How willing am I to do what is necessary to get back on track even if there is risk in doing so?

- Does the concept of narrative purpose make sense? Resonate?

- Do I see its connection to models? My model?

- How prepared am I to help the leaders I coach develop their own narratives and models independent of my own?

Notes

1. Tkaczyk, C. “World’s Most Admired Companies” [snapshot of Apple]. Fortune, Mar. 22, 2010, CNNMoney. http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/mostadmired/2010/snapshots/670.html.

2. Collins, J., and Porras, J. I. Built to Last. New York: HarperCollins, 1994, p. 78.

3. Ferguson, N. The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World. New York: Penguin, 2008.

4. Risen, C. “How the South Was Won.” Boston Globe, Mar 5, 2006. www.boston.com/news/globe/ideas/articles/2006/03/05/how_the_south_was_won/.

5. Greenberg, A. C., with Singer, M. The Rise and Fall of Bear Stearns. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010. N/A.

6. De Pree, M. Leadership Is an Art. New York: Doubleday, 2004.

7. Ward, V. The Devil’s Casino: Friendship, Betrayal, and the High-Stakes Games Played Inside Lehman Brothers. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2010.

8. Thomas J. Watson Jr., quoted in Collins and Porras, Built to Last, p. 73.

9. Hastings, M. “The Runaway General.” Rolling Stone, June 22, 2010. www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/the-runaway-general-20100622.

10. Kilburg, R. Executive Wisdom: Coaching and the Emergence of Virtuous Leaders. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association, 2006, p. 212.

11. Ibid., p. 191.

12. Ibid., p. 194.

13. Ibid.

14. Tkaczyk, C. “World’s Most Admired Companies” [snapshot of Coca-Cola]. Fortune, Mar. 22, 2010, CNNMoney. http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/mostadmired/2010/snapshots/100.html.

15. Christensen, C. “How Will You Measure Your Life?” Harvard Business Review, July-Aug. 2010. http://hbr.org/2010/07/how-will-you-measure-your-life/ar/1.