Live rooms – their revolutionary strengths and weaknesses

4.1 A brief history of idiosyncrasy

In the early days of recording, when studios were expected to be able to handle any type of recording which their size would allow, live rooms were more or less unknown. To this day, if the only recording space in a studio is a live room, then it is either in a studio which specialises in a certain type of recording, or the room is used as an adjunct to a studio which is mainly concerned with electronic music. Live rooms are distinctly individual in their sound character, and tend to impose themselves quite noticeably upon the recordings made in them. On the other hand, when that specific sound character is wanted, then effectively there is no substitute for live rooms. Electronic, or other artificial reverberation simply cannot achieve the same results, a point which will be discussed further in the following chapter on stone rooms.

When, in the late 1960s, many British rock bands began to drift away from the more ‘sterile’ neutral studios, gravitating towards the ones in which they felt comfortable and in which they could play ‘live’ in a more familiar sonic environment, a momentum had begun to grow which would radically change the course of studio design. In 1970 the Rolling Stones put the first European 16-track mobile recording truck into action. This was not only intended for the use of live recordings, but also for the recording of bands in their homes, or anywhere else that they felt at ease. It was soon to record the Rolling Stones Exile on Main Street album in Keith Richard’s rented house, Villa Nelcote, between Villefranche-sur-Mer and Cap Ferrat in the south of France, but another of its earliest uses was the recording of much of Led Zeppelin’s fourth album. This album was a landmark, containing such rock classics as ‘Stairway to Heaven’ and ‘When the Levee Breaks’, the latter perhaps inspiring a whole generation of recorded drum sounds. As mentioned in the previous chapter, Led Zeppelin had made many recordings in the famous, old, large room at Olympic, in London. For the fourth album they rented Headley Grange in Hampshire, England, and took along the Rolling Stones’ mobile, and engineer Andy Johns. The house had some large rooms, but none had been especially treated for recording. Nevertheless, as the house existed in a quiet, country location, the ingress and egress of noise was not too problematical.

4.1.1 From a room to a classic

It seems that ‘When the Levee Breaks’, with its stunning drum sound for the time, was never planned to be on the album, nor indeed to be recorded at all. In the room in which they were recording, John Bonham was unhappy with the sound of his drum kit, so he asked the roadies to bring another one. When it arrived, they duly set it up in the large hallway, so as not to disturb the recording, and waited for John to try it. At the next available opportunity, John took a break from recording and went out into the hallway to see if he preferred the feel and sound of the new kit. The other members of the band remained in their positions, relaxing, when suddenly a huge sound was heard through their headphones. The sound was from the drum kit in the hallway.

John had failed to close the door when he went out, and the sound from the kit that he was playing was picking up on all the open microphones in the recording room. The hall itself was a wood panelled affair, with a large staircase, high ceiling and a balcony above. It was thus diffusive, reverberant, well supplied with both late and early reflexions, and very much of a sonic character which matched perfectly the style and power of John’s drumming. He went into a now famous drum pattern, over which Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones began playing some guitar and bass riffs which they had been working on. Robert Plant picked up on the whole thing, and sung along with some words of an old Memphis Minnie/Kansas City Joe McCoy song. Subsequently, Andy Johns, who had been recording the sounds out of pure interest, reported from the mobile recording truck that they should consider this carefully, as he was hearing a great sound on his monitors.

Such was the birth of this classic rock recording. The story was related to me by Jimmy Page a dozen years or so after the event. I had phoned him whilst I was producing some recordings for Tom Newman (co-producer of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells I and II), as one of the songs being recorded was the one referred to above. The problem which we had was that no matter how many times we listened to the Led Zeppelin version, we could make absolutely no sense of the words in the bridge section. ‘Probably that is because they don’t make sense,’ replied Jimmy. Evidently, during Robert’s sing-along, there was no bridge lyric which he knew or remembered, so he sung what came into his head. Why I relate this story here in such detail is because it shows, most forcefully, how a room inspired an all-time rock classic. It is almost certainly true to say that without the sound of the Headley Grange hallway, Zeppelin’s ‘When the Levee Breaks’ would never have existed.

Had Led Zeppelin been recording in a conventional studio of that time, they could perhaps now have been considered to be one rock classic short of a repertoire. But, it must also be remembered that had John been playing a different drum pattern in Headley Grange, or had Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones opted for a different response, then the sound of the drums in the hallway may have been totally inappropriate. This highlights the limitation with live rooms; they can be an inspiration and a unique asset in the creation of sounds, or they can be a totally intrusive nuisance. Furthermore, there is no one live room which will serve all live room purposes.

4.1.2 Limited, or priceless?

Let us suppose that we had a reverberation chamber, similar to the ones used for acoustic power measurements in universities, institutes and research houses. These are constructed to give the broadest achievable spread of modal resonances, in order not to favour any one frequency over another. They can produce excellent results as reverberation chambers for musical mixes, but they lack the specific idiosyncratic characteristics that make special live rooms special. Let us now consider an analogous situation where guitar manufacturers opt for a totally even spread of resonances in their instruments; to have ‘life’, but as uniformly spread as possible. All of a sudden, almost all guitars would begin to sound much more alike than they currently do. In general, it is impossible to make a Fender Stratocaster sound like a Gretch Anniversary, or vice versa, because the time domain responses of the resonances and internal reflexions cannot be controlled by the frequency domain effects of an equaliser. Something halfway between a Stratocaster and an Anniversary would be neither one thing nor the other, and whilst it may well be a valid instrument in its own right, it could not replace either of the others when their own special sounds were wanted.

Another analogy exists here in that most professional guitarists have a range of instruments for different purposes: different music, different arrangements, different styles and so forth. No famous guitarist that I know has a ‘universal’ guitar. Such is the case with live rooms, where a ‘universal’ room could be used as an acoustic reverberation chamber for the recording and mixing process, but could never be used to substitute for the special sounds of the special rooms. What is more, no large, self-respecting recording studio has banks of identical ‘best’ electronic reverberation devices, but rather a range of different ones. It is generally recognised that a range of different artificial reverberation is greatly preferable to more of ‘the best’. In so many cases, neutrality is quite definitely not what is called for.

I recall speaking to Dave Purple, who was formerly at dbx in Boston, USA. In the 1960s he was an engineer at Chess Records in Chicago, when they had the big EMT 140 reverberation plates. These consisted of spring mounted steel sheets, about 2 m 1 m, with an electromagnetic drive unit and two contact pick-ups. Dave told me that at Chess they used to heat the room where the plates were kept to about 30°C, then tension the plates. When the room cooled down on removal of the heaters, and if they were lucky and the springs did not snap as the steel contracted, the plates produced a unique sound. More often than not, however, the springs did snap, and the whole process would have to be tediously repeated until it succeeded in its aims. Some of the earliest recordings which inspired me to work in this industry were the Chess recordings of Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry; partly due to their powerful and distinctive music, but partly also for their unusual sounds. Somewhat unusually, for the time, the Rolling Stones went to Chicago specifically to record in the old Chess studios at 2120 South Michigan Avenue, and its unique sounds can still clearly be heard on a number of their older recordings.

The old EMT plates were very inconsistent, and though their German manufacturers guaranteed their performance within a quite respectably tight specification, the sonic differences achievable within that specification were enormous. What Chess were doing would have had the EMT engineers tearing their hair out, but it got Chess the sound which was a part of their fame, so in such circumstances, specifications were meaningless. The irony here is that whilst EMT were trying to make widely usable, relatively neutral plates, Chess were doing all they could to give their plates a most definitely un-neutral sound. This situation was a perfect parallel to what was happening in the development of live rooms for studios, where the musicians and engineers were looking for something other than what the room designers were offering them. I recall also, in 1978, when building the Townhouse studios in London, desperately trying to buy a specific EMT 140 plate from Manfred Mann’s Workhouse studios. I had done some recordings there for Virgin Records, and had been impressed by the sonic character of one of their plates in particular. I offered them a really ludicrously large amount of money for the plate, but short of buying the whole studio, towards the success of which the plate had no doubt contributed, there was no way that Manfred Mann and Mike Hugg would sell it. In fact at one stage, I actually did come close to closing a deal on the whole studio, which also had a wonderful sounding API mixing console.

In the Silo studios in West London in the early 1980s, they had intended to build a large studio room with a small drum room, connected to the studio via a window. The proposed drum room was about 3.5 m 2 m, and about 2 m high. This was happening right at the time when the backlash against small, dead, isolated drum rooms was reaching a peak, and once the owners realised that their ideas were out of date, they stopped work on the room. When the studio opened, the proposed drum room remained just a concrete shell, with a window and a heavy door. I recorded some of the best electric rock guitar sounds that I have ever recorded with amplifiers turned up loud in that room. This pleased the owners, as their ‘white elephant’ had become a famous guitar room. The density of reflexions when the room was saturated with an overdriven valve (tube) amplifier combo was stunning. The ‘power’ in the sounds, even when at low level in the final mixes, was awesome, yet the problem with this room was that for almost any other purpose it was a waste of space. Neither this room, nor Manfred’s plate, nor the Chess plates, nor the Headley Grange entrance hall would have had any significant place outside their use for certain very specific types of music and instrumentation.

In another instance, I was fortunate enough to be one of the engineers on a huge recording of Mahler’s Second Symphony for film and television – and what is now one of the CBS Masterworks CD series. It was performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, the 300-piece Edinburgh Festival Choir, two female soloists, an organ, and an ‘off stage’ brass band. It all took place over four days in Ely Cathedral, England, which the conductor, Leonard Bernstein, had specifically chosen for its acoustics and general ambience. This was a masterful choice by a genius of a conductor, but despite the wonderful acoustics of the cathedral for orchestral/choral purposes, it would have been entirely unsuitable for any of the other recordings discussed so far in this chapter. They would simply have been a mess if recorded here. Yet, conversely, perhaps there was no studio that could have hoped to achieve a recording with the sound which we captured in the cathedral.

4.1.3 Difficulties for designers

The Kingsway Hall in London was an example of another great room for the recording of many classics, despite its sloping floor and problems from the noises of underground trains, aeroplanes and occasional heavy traffic. It was an assembly hall, never specifically designed for musical acoustics, yet it far outstripped the performance of any large orchestral studio in London at the time. Unfortunately, I believe that it has now been demolished.

On the other hand, specifically designed concert halls have been criticised for their failure to live up to their expected performance, though such criticism has not always been fair. Concert halls must cater for a wide range of musical performances, so tend to some degree to have to be ‘jacks of all trades’ rather than ‘masters of one’, the latter of which is perhaps more the case with Ely Cathedral. To experience Mahler’s Second in Ely, or to have heard some Stockhausen in Walthamstow Town Hall would show just how appropriate those venues are, but Stockhausen in Ely Cathedral? … Perhaps not! Unfortunately, though, purpose-built concert halls would be expected to reasonably support both, at least adequately, if not optimally. As yet, you cannot design a general purpose concert hall or recording studio to equal the specific performances of some accidentally discovered recording locations for certain individual pieces of music. Neither can you build one live room to equal the performances of Headley Grange, the Silo’s concrete room, Manfred Mann’s plate, and the old Chess Studios. Brass bands, chamber orchestras, symphony orchestras, choirs, organs, folk music, pan pipes, and a whole range of other instrumentation or musical genres all have their own requirements for optimum acoustic life. The bane about the ‘best’ live rooms is that they gain their fame by doing one thing exceptionally well, but for much of the rest of the time they lie idle. If one is not careful, they can be something of an under-used investment, which is why many studio owners opt to use whatever limited space they have for rooms of more general usability.

The complexity of the acoustic character of live rooms is almost incomprehensible, and they are often designed on intuition, backed up by a great deal of experience, as opposed to any rules of thumb or the use of computers. Just as no computer has yet analysed the sound of a Stradivarius violin or shown us how to make one, full computer analysis of what is relevant in good live rooms is beyond their present capabilities: the modelling of surface irregularities is not possible, unless the position and shape of every surface irregularity were known in advance, and in greater detail than is realistically possible. Designs are thus usually ‘trusted’ to designers with experience in such things, but in almost every case, some engineer or other will declare the result ‘rubbish’ because it fails to do what he or she wants it to do. The lack of a fixed specification for a great room can also lead to other nonsenses.

I once visited a studio with a live room designed by a very well-known acoustician. When I was shown into it by its proud owners, I was shocked. Not only was this a travesty, it was a crime against acoustic decency. I could not understand how a designer of such repute could have done this, and wondered how, if I should later meet the person face-to-face, I could ask how it had occurred, whilst still being tactful. As it happened, I discovered some months later that it was not the designer’s fault at all. What had happened was that one of the studio owners did not like the look of the original stone, so ordered the builders to use expensive-looking polished granite slabs. As a result, the place not only looked like a bathroom, but sounded like one as well. Unfortunately, such is the level of acoustic ignorance which all too frequently pervades this industry.

After hearing the reason for the above nonsense, I immediately thought back to a studio which I designed in 1985, funded largely by local government and unemployment reducing schemes. The money had to be spread over a range of departments of the co-operative, and my role as acoustic designer had to pass through a strangely concocted committee. As it is unusual to find good acoustic designers on the unemployment registers, they had to resort to my professional help for this service, but there were trained, unemployed interior designers on the committee. The co-operative asked for a live room, so I designed a room, which had to be relatively inexpensive, with rough slabs of York stone for the walls, and coloured concrete slabs for the floor. However, in my absence the interior designers decided that they could make pretty patterns on the walls with the coloured concrete slabs so instructed the building labourers to reverse the positions. As a result, not only did the room not sound as I had hoped (though they were lucky, as it was not too bad) but they had a devil of a job wheeling pianos and flight cases over a rough flagstone floor. Political correctness, interior decoration and live room acoustics are not always happy bed-fellows. Remember the old saying about a camel being the result of a committee trying to design a racehorse!

4.2 Drawbacks of the containment shell

The question is frequently asked as to why so many great acoustics are found in places not specifically designed to have them, and why so many places which are specifically designed to have good acoustics are frequently not so special. For example, why is the fluke sound of the entrance hall at Headley Grange so difficult to repeat in a studio design? Well, part of the problem was discussed in Chapter 1. Studios tend to be built in isolation shells, which reflect a lot of low frequency energy back into the room. This reflected energy must then be dealt with by absorption, which in turn takes up a lot of space and generally changes the acoustic character of the rooms to a very great degree. The old Kingsway Hall in London was used for so many classical recordings because of its very special acoustic character, but its drawbacks were tolerated in a way which they never would be in a recording studio. Many good takes were ruined by noise, and had to be re-recorded, but because it was not a recording studio, this was a hazard of the job. Ironically, a purpose-built recording studio with similar problems would be open to so much argument and litigation that it would not be a commercial proposition, even if it had the magic sounds. People would not tolerate such problems in a building actually being marketed as a professional studio; their expectations would be different.

The Kingsway Hall had windows through which many noises entered, as they also did through the floor and general structure. On the other hand, these were the selfsame escape routes which allowed much of the unwanted sounds to leave, such as the sounds which would cause low frequency buildups. Structural resonances could, in turn, change the sound character, and remember, once again, that most instruments were developed for sounding their best in the normal spaces of their day. Once we build a sound containment shell and a structurally damped room, we have a new set of starting conditions. However, if we are to operate a studio commercially, without disturbance to or from our neighbours, and offer a controlled and reliable set of conditions for the musicians and recording staff, such a containment shell is an absolute necessity.

Containment shells usually operate by reflecting much of the sound back into the enclosed spaces, and once we bounce the acoustic energy back into the space in a way which is untypical of ‘normal’ rooms, we then must deal with it in other ‘abnormal’ ways, the interactions of which are extremely complex. This is especially the case in smaller sized rooms. If we consider again the entrance hall at Headley Grange, it is a relatively lightweight structure which is acoustically coupled via hallways, corridors and lightweight doors into a rabbit warren of other rooms. Effectively, the sound of the hallway is the sound of the whole Grange, and if we were to contain the hallway in an isolation shell and seal all the doors and windows, then we would end up with a room having a very different sound to the one which it actually has. Unfortunately, I have never yet had a client for a studio design who would give me a building the size of a mansion house only to end up with a recording space the size of its hallway, yet this is what it would possibly take to create a sonic replica.

The above fact is borne out by the case of a studio which I once built in a large decaying city. A troublesome area of the city with a very high crime rate had been partially cleared and the residents resettled elsewhere. Only a few businesses remained, but the city was almost broke and could not continue the redevelopment, so had allocated old industrial buildings, very cheaply, to partly public-financed business start-up programmes. I was asked by an established studio company to design a new studio in a building which they had managed to rent very cheaply from the local government, and the building was virtually without any noise-sensitive neighbours. What was more, the nearby traffic was only light, and it was not under the flight path of any airport. Acoustic control shells were constructed in the building, without any containment (isolation) shells. The only isolation wall was the one directly between the control room and the nearest studio room. The low frequency response of the control room was perhaps the most powerful, tight, and musical of any studio that I had ever built.

As so many of the neighbours of hi-fi enthusiasts are all too painfully aware, most domestic buildings have very poor sound isolation, yet it is this fact which makes so much domestic hi-fi sound acceptable in untreated rooms. Whatever acoustic losses the rooms cannot provide by absorption, they provide by transmission (letting the sound pass through). This is one reason why the bass in many homes is more ‘true’ than in many simple studio control rooms. For isolation purposes, much LF energy must remain trapped in many control rooms by their isolation shells. The performance of the control room referred to in the last paragraph was undoubtedly largely due to the lack of an acoustic containment shell, which is the same reason that so many non-specifically designed recording rooms achieve results that can be hard to mimic when all the design considerations of a specifically designed studio must be addressed.

There is also another aspect of recording in live rooms which, whilst unrelated to acoustics, is so fundamental in their use that it should be addressed. Reproducing the exact acoustic of Headley Grange would not guarantee a Led Zeppelin drum sound. There were five other very important factors in that equation. John Bonham, his drums, the other members of the band, the song, and Andy Johns. Time and time again I am asked to produce rooms which sound like some given example, but in the case in point, John Bonham was a drummer of legendary power, and he also had the money to afford to buy good drum kits. The engineer, Andy Johns, the brother of another legend, Glyn, had been well taught in recording techniques. He also had the excellent equipment of the Rolling Stones mobile truck at his disposal, and considering his brother’s fame, perhaps also had a natural aptitude and a pair of musical ears. He knew where to put microphones, and where not to put microphones. He trusted his own ears and decisions, and he had excellent musicians and instruments to record.

Shortly after the death of John Bonham, Jimmy Page and Robert Plant booked the Townhouse studios in London to play back some 24-track tapes which they had been recording. If I remember rightly, this was part of the process of deciding if they could continue with another drummer, or whether Led Zeppelin would die with John Bonham. At the time, we had an assistant engineer, George Chambers, who was very inexperienced, but, as it was only a playback and our other staff were otherwise occupied, we put George on the session. He was petrified during the afternoon before the session, saying that he did not know how to get sounds like Led Zeppelin, and what would he do if they asked him to change a sound or something. He was reassured that there would be no problems, and I distinctly remember an ashen-faced George when the musicians arrived about 7 pm. Around an hour later, he came bursting into the lounge almost speechless with excitement. ‘It’s incredible, it’s incredible’ he was saying, ‘I just pushed up the faders and it was all there!’

The story took me back to the early 1970s when I found out that I had to record Ben E. King, the former lead singer of the Drifters. I had wondered many times previously how to get vocal sounds such as I had heard on ‘Spanish Harlem’ and his other big hits. Indeed, I had been faced many times with mediocre musicians who wanted me to create some sort of recording magic, and to transform their voices or instruments into that of some famous artiste. Like George, I had also felt some trepidation before the Ben E. King recording. What microphone should I use; or, was the great vocal sound achieved by some compression technique? Was it some equalisation, or reverberation, or echo? What was more, would my career be ruined when I failed to capture the magic vocal sound? On the day in question, I put up several excellent microphones, and tried to have all options covered; then, surprise surprise, when he arrived, regardless of which microphone I used, I simply had to raise the fader and the magic sound of the voice of Ben E. King was issuing from the monitors in all its splendour.

I hope that I am not labouring this point, but a great live room is not a magic potion in its own right. It can enhance the performance, or even, as we have seen, inspire the performance of musicians, but nothing can substitute for starting off with good musicians, good instruments, good recording engineers and good music. Good recording equipment is also important, but is generally secondary to the previous items. Good and experienced musicians will react to a good room and play to its strengths. They will not simply sit there playing like robots. The whole recording process is an interactive process, hence the care which must be taken to avoid anything which could make the musicians uncomfortable.

Live rooms can inspire performances, both as we have already seen, and as we shall see further in the chapter on stone rooms. Visual aesthetics are also an important contributing factor, but there are some things which just have to be. The acoustical demolition of the rooms by the interior decorators, as we discussed earlier, is a case in point. Some things in live rooms are there because designers have to compensate for other things, such as isolation shell interference or the variability of personnel and equipment which may be placed in the rooms during their use. Remember, they often need to re-create the acoustic of a more usual space within a very unusual shell, and this may in itself require some unusual architecture.

The materials which are used to create these internal acoustics are very important in terms of the overall sound character of the rooms. Wood, plaster, concrete, soft stone, hard stone, metal, glass, ceramics and other materials all have their own characteristic sound qualities. Within the range of current response specification, it may be almost impossible to differentiate between the response plots of rooms of different materials, yet the ear will almost certainly detect instantly a woody, metallic, or ‘stoney’ sound. In general, all the above materials are suitable for the construction of live rooms, and it is down to the careful choice of the designer to decide which ones are most appropriate for any specific design. The overall sound of the rooms, however, will tend to have the self-evident sound quality associated with each material. Wood is generally warmer sounding than stone, and hard stone is generally brighter sounding than soft stone. Geometry and surface textures also play great parts in the subjective acoustic quality.

4.4.1 Room character differences

I suppose that live rooms should now be split into two groups, reflective rooms and reverberant rooms. The former tend to have short reverberation times, but are characterised by a large number of reflexions which die away quickly. The reverberant rooms tend to have a more diffusive character, with a smooth reverberant tail-off. The reflective ‘bright’ rooms also often employ relatively flat surfaces, though rarely parallel, and a considerable amount of absorption to prevent a reverberant build-up. The reverberant rooms on the other hand tend to employ more irregular surfaces, and relatively little absorption. It is possible to combine the two techniques, but the tendency here is usually towards rooms which have very strong sonic signatures, and consequently their use becomes more restricted.

The question often seems to be asked as to why flat reflective surfaces in studios usually sound less musical than they do in the rooms of many houses or halls. Well, notwithstanding the isolation shell problem, studios rarely have the space-consuming chimney breasts, staircases, furniture, and other typical domestic artefacts. These things are all very effective in breaking up the regularity of room reflexions, but studio owners usually press designers for every available centimetre of space. It has been my experience that far too many of them are more interested in selling the studio to their clients on the basis of floor space rather than acoustic performance. (Never mind the sound … look at the size!) Perhaps this is to a large degree the fault of the ignorance of the clients as much as that of the studio owners. There is possibly too much belief today in what can be achieved electronically, and the importance of good acoustics is still not appreciated by a very large portion of studio clients. Of course, those who do know tend to produce better recordings by virtue of having had the luxury of better starting conditions, and leave the mass market wasting huge amounts of time trying to work out exactly which effects processor programme they used in order to get that sound. The answer of course is that good recorded sound usually needs little or no post-processing, unless, that is, the processed sound is the object of the recording.

When people say that a given domestic room has a great acoustic, the usual situation is that on hearing a certain instrument in that room, their attention has been called to the enhancement of that instrument in that position in that room. A whole range of other instruments in the same room, either separately or together, may sound very unimpressive. I recall once recording an album for a well-known flautist in a cottage. We recorded almost all of the flute recordings in a small toilet, using a Shure SM57 microphone. We wanted a powerful sound, which suited perfectly the style of music, and we were very pleased with the outcome. Nevertheless, this does not mean to say that flutes, per se, should be recorded in toilets with SM57s; nor does it mean that studios should have toilet-sized rooms lined with ceramic tiles if they want a good flute sound. Such a room would receive very little use, and anyhow, 95% of the time I would prefer to record a flute with a Schoeps condenser microphone and in a more spaciously ambient environment. However, it only seems to take one famous recording to use a given technique, and a huge proportion of the industry will try to copy the technique, believing that it is the way to record that instrument. I hope that I am exaggerating here, but I fear that I am not!

I hope that what this chapter is beginning to get across is the point that there are almost no absolute rights or wrongs in terms of live-room design. Whatever a designer provides, there will always be people coming along who have heard ‘better’ elsewhere. It is also surprising how one famous recording made in a room will suddenly reverse the opinions of many of the previous critics, who will then flock to the studio for the ‘magic’ sound. Creating good live rooms is like creating instruments – certainly to the extent that the skill, intuition and experience of the designer and constructors tend to mean more than any textbook rules.

I attempted when writing this to at least give a list of taboos, but every single time that, off the top of my head, I considered something to be absolutely out of the question for wise room design, I found that I could think of an example of a room flouting such regulations from which I have heard great results. Large live rooms are unusual in that, beyond their existence in a somewhat acoustically controlled form, as, for example, the rooms used for selected orchestral recordings, they are normally to be found outside of purpose-designed recording studios. Their use tends to be too sporadic to allocate such a large amount of space to occasional use.

4.5.1 Driving and collecting the rooms

Most smaller live rooms do at least appear to have one thing in common: recording staff must learn how to get the best out of each one individually. The modal nature of such rooms defies any reasonable analysis: the complexity is incredible. The positions of sound sources within the rooms can have a dramatic effect on determining which modes are driven, and which receive less energy. An amplifier facing directly towards a wall will, in all probability, drive the axial modes very strongly. However, precisely to what degree they will be driven will depend upon such things as the distance between the amplifier and the facing wall, or whether the loudspeaker is in a closed box, or is open-backed.

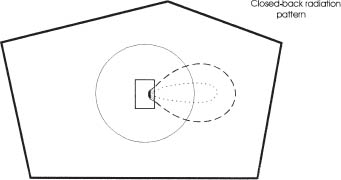

Positioning the amplifier (or at least its loudspeaker) on an anti-node, where the modal pressure is at a peak, will add energy to the mode, and resonate strongly at the natural frequencies of the mode. Placed on a node, where the pressure is minimal, that mode will not be driven, and its normally strong character in the overall room sound will be overpowered by other modes. Positions in between will produce sounds in between. If the cabinet is open-backed, it will act as a doublet (or figure-of-eight source), radiating backwards and forwards, but very little towards the sides. A closed-back cabinet at lower frequencies, say between 300 and 400 Hz, will, if facing down the length of a room, drive the low frequency axial modes of all three room axes – that is, floor to ceiling, side wall to side wall, and front wall to back wall. With an open back, however, only one axial mode will be driven, the axis along which the loudspeaker is facing. Figure 4.1 shows the typical radiating pattern of open- and closed-backed cabinets.

Microphone positioning in such rooms is also critical. A microphone placed at a nodal point of a mode will not respond to that mode, as it is at the point of minimal pressure variation. Conversely, at an anti-node (a point of peak pressure), the response may be overpowering. Microphone position can be used not only to balance the relative quantities of direct and reverberant sound, but also to minimise or maximise the effect of some of the room modes. Furthermore, more than one microphone can be used if the desired room sound is only achievable in a position where there is too little direct sound. Another parallel to the ability of amplifiers to drive a room is the ability of the microphones to collect it. Variable pattern microphones can produce greatly different results when switched between cardioid, figure-of-eight, omni-directional, hyper-cardioid, or whatever other patterns are available. What is more, certain desirable characteristics of a room may only be heard to their full effect via certain specific types of microphones.

If the amplifiers are set at an angle to the walls, they will tend to drive more of the tangential modes, which travel around four of the surfaces of the room. If the amplifiers are then also angled away from the vertical, they will tend to drive the more numerous, but weaker, oblique modes. At least this will tend to be the case for the frequencies which radiate directionally. Precisely the same principle applies to the directions which the microphones face in respect of their ability to collect the characteristic modes of the room. If more than one microphone is used, switching their phase can also have some very interesting effects. Given their positional differences, the exact distance which they are apart will determine which frequencies arrive in phase and which arrive out of phase, but there is no absolute in- or out-of-phase condition here, except at very low frequency in small rooms. A pair of congas which sound great in one live room, may not respond so well in another. Conversely another set of congas in the first room may also fail to respond as well. But, there again, in another position in the room perhaps they will. It could all depend on the resonances within the congas, and if they matched the room dimensions. The whole thing depends on the distribution of energy within the modes, the harmonic structure of the instruments, and the way the wavelengths relate to the coupling of the room modes.

(a) High frequencies propagate in a forward direction, but low and mid frequencies largely radiate in a figure-of-eight pattern

(b) As with (a), the high frequencies still show a forward directivity, but, in this case, the mid frequencies also radiate only in a largely forward direction, and the low frequency radiation pattern becomes omnidirectional

Figure 4.1 Comparison of open- and closed-back loudspeakers in the way that they drive the room modes

Hopefully, from all this discussion, it will by now be clear that live rooms are musical instruments, and share many of the characteristics of other musical instruments. The proliferation of freelance recording engineers and producers, travelling from studio to studio, often leaves them having to deal with a strange live room in a somewhat similar way that musicians have to deal with strange instruments. Musicians, in fact, generally do not like to have to play strange instruments. Their instruments are very personal, and over a period of time, they get used to the feel of them and learn how to get the best from them. The frequent travelling between studios does not always allow freelance engineers the time to learn how to get the best from many live rooms, which, in the hands of a permanent and experienced studio staff, would be capable of producing some very interesting sounds. We could even draw a parallel with sports, such as Formula One motor racing. All drivers entering a Grand Prix race have a great deal of experience, yet if they were all to swap cars at the beginning of a race, perhaps very few would even finish the race. Racing without having learned the individual feel of the strange cars would lead to a chaotic and dangerous race. In fact if such a race was proposed, I am sure that many drivers would refuse to take part. However, without the life-threatening risks in the studio business, people do sometimes launch themselves on such misguided pursuits, then wonder why the results do not come up to expectation. No matter how much general experience an engineer may have, learning about live rooms is a very individual process. It takes time to get to know them, at least if their full potential is to be realised.

Live rooms are great things to have as adjuncts to other recording facilities, but they are a dangerous proposal if they form the only available recording space, unless the studio is specialising in the provision of a specific facility and the recording staff know the characteristics of the room very well indeed. These rooms have grown in popularity as it has become apparent that electronic simulation of many of their desirable characteristics is way beyond present capabilities. They have also been able to provide individual studios with something unique to each one, and this point is of growing importance in an industry where the same electronic effects with the same computer programmes are becoming standardised the world over. If a certain live room sound is wanted, it may well bring work to the studios which possess it, as the option to go elsewhere does not exist. But be warned, they can bite! The design and use of these rooms are art-forms in their own right, and very specialised ones at that.