The history of record keeping in the UK museum and gallery sector

Abstract:

Outlines the development of records management in the UK museum sector, international legislative catalysts and record-keeping standards; defines record-keeping roles and activities, and types of museum records; and describes the difference between records, archives and collections.

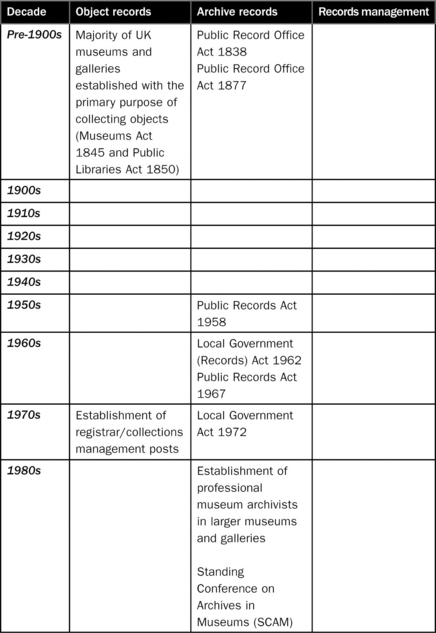

History

Within the museum environment, the value of good records – at least in one regard – has long been recognised. With the notable exception of the British Museum (established in 1753), the majority of national museums and galleries in the United Kingdom were founded in the Victorian era.1 Local authority museums also have a long history. The general tendency towards reformism and middle-class paternalism of the time prompted both the Museums Act of 18452 and the Public Libraries Act of 1850, which together stimulated an enormous growth in museums in towns with a population of more than 10,000 people. Collections given to local communities by both charitable societies and individuals were housed in civic buildings. As a direct result, many museums and galleries were founded, including those in Exeter, Brighton, Nottingham, Liverpool, Wolverhampton, Birmingham, Aberdeen, Sheffield, Leeds and Preston.3 In Scotland the legal framework for local authority museums also dates from this period. The Public Libraries (Consolidation) Act 1887 gave local authorities the power to establish museums and galleries. Alongside collecting objects, many of these museums acted as archival repositories, housing important collections of papers and documents.

It was also at this time that record keeping became an established discipline. The Public Record Office Act was passed in 1838 to reform the keeping of public records, which were being held, sometimes in poor conditions, in a variety of places. Although it initially applied only to legal documents, by the 1840s the papers and documents of government departments were also accepted for permanent preservation. This arrangement was legalised by an order in Council issued in 1852. A purpose-built repository to house the material was constructed between 1851 and 1858. Although it functioned primarily as a repository for the records of central government, record keeping became an important activity in most public offices. Clerks were employed specifically to create and maintain good records.

In the museum environment, the focus of this record-keeping effort was centred almost exclusively on the ‘object’. The role of museums was to collect objects according to their subject areas or collecting policies, and thereafter to identify/catalogue, preserve, interpret and present these to the public. The staff employed to carry out this work, keepers, directors and curators, were well aware they needed to document their collections. Indeed, record keeping was seen as an extension of curatorial activity, and was often carried out meticulously. The combined effect of this Victorian obsession with record keeping and the curatorial focus on documenting objects helped ensure that most museum archives from this era contain a reasonably good record of activity from the early years of their history, albeit collection-focused.

As museums expanded in the twentieth century, record-keeping activities concerned with the collection began to grow. While curators remained responsible for creating research and interpretation-related records, the task of documenting objects became the preserve of a new post: the registrar. As well as recording the acceptance of objects into the collection, the role of the registrar was to document any movement of those objects within and outside of the institution. By the 1970s registrar posts (sometimes also called collections manager posts) began to be introduced in the sector. They are now commonplace in most large museums and galleries.

By 1991 object documentation was a formally recognised core museum function: many institutions now employed whole departments to carry out this work, and further steps were taken to develop and refine the discipline. An impetus to standardise practice across institutions (partly driven by developments in information technology) led to the development of SPECTRUM, the UK museum documentation standard. The purpose of SPECTRUM is to establish ‘a common understanding of good practice for museum documentation’ (Collections Trust, 2008: 21). The standard was compiled as a collaborative effort by over 100 practising museum professionals. When it was published in 1994 it identified all the functions common to museums and established the procedures and information required to manage these functions effectively. It was a huge achievement and proved invaluable to those in registrar or collections management roles. SPECTRUM is now accepted as the UK and international standard for collections management. In its third edition, it is published by the Collections Trust as an open standard on behalf of the libraries, archives and museums sector.

Although SPECTRUM focuses squarely on documenting museum objects, it does contain some information of use to records managers, or those concerned with general record keeping in a museum environment. By identifying activities familiar to museums, it is possible to extrapolate the types of record series that may be created and determine something of their relative value. By including statements like ‘documentation is essential for any organisation which holds a collection’, it hints at the value of good record keeping in general. It also contains specific information of interest to records managers. For example, the section on acquisition determines that:

the accession register… should be made of archival quality paper and be bound in permanent form. If a computer system is being used, copies of new records should be printed out on archival quality paper using a durable print medium and securely bound at regular intervals. The print-out should be signed and dated, preferably on every page. The original register should be kept in a secure condition, ideally in a fire-proof cabinet. (Ibid.: 72.)

However, for the records manager SPECTRUM is ultimately rather narrow. Throughout its 395 pages, the focus is solely on documentation and other information associated with objects. Museum records in their wider sense are barely mentioned.

Since objects are the raison d’être of most museums, this record-keeping bias is wholly understandable. Object records are mission critical; museums simply cannot function without them. In order to conduct everyday business, a museum must have access to records concerning the acquisition, location, conservation, loan and so on of the items in its collection. These records are necessary for staff in all departments to do their jobs. For some of the national museums, keeping object records is a statutory duty. The Museums and Galleries Act 1992 declares that alongside the objects themselves certain museums must keep ‘documents relating to those works’.4 As with the objects, they must care for, preserve and provide access to these documents. This record-keeping effort has produced a plethora of documentation. Along with object files, which may contain records about a whole range of activities concerning items in the collection, a museum is also likely to maintain records detailing wider collections management issues, such as acquisitions or accessions, loans and disposal registers.

Until relatively recently, the value of records related to other museum functions – those documenting wider administrative and business activities – was largely overlooked. For example, records concerning building maintenance, development, finance, staff, exhibitions and projects had always been created, but little consideration had been given to their management beyond this point.

The Public Records Acts of 1958 and 1967, which apply to all national museums and galleries, began to change this. They give public institutions a duty to create, preserve and provide access to the records documenting their activities. The Acts prompted museums to consider the value of their records outside the institution: they were no longer viewed primarily as working tools for staff. As a result, many museums began to retain material that might previously have been destroyed and institutional archives (albeit sometimes unknowingly) were founded. The 1967 Act introduced the ‘30-year rule’, which established a standard period after which records should be transferred to the Public Record Office5 (PRO) and made available to the public. In the museum environment, this generally meant that records were retained in their entirety – little consideration was given to what might have long-term value and what might be destroyed. There was still no systematic records management.

Under the terms of the Acts, museums and galleries – classed as non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs) – were subject to the same rules as central government. They differed on one significant point: unlike central government, museums and galleries were not required to transfer archive records to the PRO. It was recognised that museums needed their records on site to carry out everyday business. Designated places of deposit, they could keep their own records so long as these were maintained in a manner considered satisfactory by the PRO, which carried out regular inspections to ensure that this was the case. This had a significant impact: allowed to manage their own records, record-keeping practice in museums was far less stringent. Unlike government departments, which often operated centralised filing systems or registries, and carefully managed records from creation to destruction or transfer to the archive, many museums tended to retain their records without due consideration of the process that this should entail.

In the 1980s the PRO began to foster closer relationships with NDPBs. It issued guidance, held meetings and conducted more regular inspections. As a result, there was growing awareness of record-keeping best practice (albeit archive-focused) in the national museum sector.

There is no single piece of archival legislation that requires the provision of archive services at a local or regional level for records that have been created by a relevant administrative body. However, a number of Acts go some way towards safeguarding historical records. The Local Government (Records) Act 1962 confers limited discretionary powers for local authorities to provide certain archive functions, but the focus is primarily on service provision. Section 1(1) of the Act states that ‘a local authority may do all such things as appear to it necessary or expedient for enabling adequate use to be made of records under its control’. The Local Government Act 1972 includes recommendations about stewardship. It states that local authorities must ‘make proper arrangements with respect to any documents that belong to or are in the custody of the council or any of their officers’.6 It was not until 1999 that the Department for Communities and Local Government attempted to define ‘proper arrangements’. Even with this guidance in place, there was no regulatory or monitoring process to verify compliance. For the many museums run by local authorities there was no imperative to manage records.

The establishment in 1989 of the Standing Conference on Archives in Museums (SCAM) was a significant event. It indicated that museum archives were finally being considered seriously within the sector. SCAM was formed as a partnership of three organisations: the Museums Association, the Society of Archivists7 and the Association for Independent Museums. Members from each group met regularly to discuss the special problems of managing archives in a museum environment. The ultimate aim was to promote research, training, awareness and cooperation about the issues involved at both national and local levels. In 1990 SCAM published the Code of Practice on Archives for Museums and Galleries in the UK. This offered advice to all museums on managing archives according to professional standards. It also suggested additional sources of assistance.

In 1996 the publication of the General International Standard for Archival Description (ISAD(G)) also helped promote archives in the museum environment. Although British archivists had previously looked to the Manual of Archival Description (Cook, 1984) for best practice regarding how to describe archival material, ISAD(G), developed by a committee of the International Council on Archives, addressed a much wider audience. For the first time, individuals responsible for archive materials had internationally accepted guidance on how to catalogue the records in their care. The importance of ISAD(G) to the museum sector was that it helped establish archive management as a distinct discipline and emphasised the separate identity of archives; they were not like museum objects and so must be managed very differently.

Meanwhile, the work of SCAM continued to focus primarily on records selected for permanent preservation. Between 1989 and 2003 it produced five information sheets. The first four concern museum archives; it is only in the final sheet that ‘administrative records’ are considered (SCAM, 2003). The publication of this guide is significant because it marks a culture shift in the museum sector. For the first time it was recorded that along with documentation about collections, ‘most museums create and keep large quantities of other records, such as accounts, building and installation plans, exhibition files and membership records’ (ibid.: 1). The sheet also gives a definition of records, explaining that the term is not always clearly understood, and what it might include in a museum environment (ibid.: 2).

The SCAM publication is excellent – it distils the relatively complex issue of records management in a museum environment into nine key clear paragraphs. However, the subjects covered belie the state of record keeping in the sector. Together with useful summaries of key concepts, the guide includes basic advice about how to create intelligible records in the first place. For example, section 3 states that it is a good idea to ensure records are dated and stored in files, rather than as loose documents. Inclusion of this basic type of information clearly demonstrates that, at least in some spheres, record keeping in the museum environment was rudimentary.

Spoliation

Between 1998 and 2000 four significant events8 highlighted the need for good record keeping. The first of these was the endorsement by 44 governments at the Washington Conference on Holocaust Assets in December 1998 of a statement of principles aimed at redressing one of the wrongs of the Second World War: the spoliation9 of works of art by the National Socialist (Nazi) government.

In the UK, work on spoliation was headed by the National Museum Directors Conference (NMDC), a UK-wide voluntary association of 25 cultural institutions partially funded by central government. In June 1998 the NMDC established a working group to investigate the issues surrounding spoliation, draw up a statement of principles and propose actions for member institutions. The statement was finalised and adopted by the NMDC in November of that year, and presented to the Washington Conference the following month. It included the proposal that each national museum, gallery and library draw up an action plan setting out its approach to research into the issue of provenance. A similar statement was issued by the Museums and Galleries Commission10 in April 1999, as guidance for non-national museums and galleries and a group of university and local authority museums.

The outcome of these events was that museums, galleries and other cultural institutions in the UK (like their counterparts around the world) were required to undertake detailed research into the provenance of works in their collections in order to identify those with uncertain provenance for the period 1933–1945. To do this, museum staff were required to consult their records. Indeed, the ‘statement of principles and proposed actions’ endorsed by the Washington Conference makes this point very clearly:

Principle 2. Relevant records and archives should be open and accessible to researchers, in accordance with the guidelines of the International Council on Archives. (National Museum Directors Conference, 1998)

Over the next few years extensive research was carried out in the records and archives of museums and galleries across the UK. The results are available on the NMDC website: each institution submitted a list of works with uncertain provenance.11 In total 22 national and 24 non-national museums and galleries took part in the effort; each subjected its object records, accession registers, trustee minutes, curatorial correspondence and other relevant records to scrutiny. It was a nationwide (even international) endeavour that clearly demonstrated to the sector the need for and value of good record keeping.

Other legislative catalysts

On 24 October 1998 the European Union (EU) Data Protection Directive (95/46/EC) came into effect in the UK through the Data Protection Act 1998 that received Royal Assent on 16 July. The directive’s aims were to protect human rights and freedoms in respect of personal data processing and to facilitate the free flow of data within the EU. By allowing people to request any and all personal data held about them by an organisation, and simultaneously requiring organisations to protect personal data they held from unauthorised access, it had a significant impact on the work of archivists and records managers in the UK. The Act applies to institutions responsible for processing personal data.16 It therefore encompasses all types of national, local, charity, university and regimental museums.

The 1998 Act replaced the Data Protection Act 1984 and its provisions are much broader in scope. Specifically, while the 1984 Act applied only to data held in electronic form, the new Act was expanded to include manual data held in ‘relevant filing systems’. For the museums and galleries sector this was significant: records historically collected for years in paper format – concerning donors, lenders, members, patrons and visitors – all contained personal data and were therefore likely to be affected.

Some of these records were also non-object-related records, so they had traditionally been subject to less rigorous management. The Act forced the sector to move away from its focus on archive records, and to consider how it collected and managed current records and the data they contained. In particular, Principle 5 of the Act, which states that that personal data shall be ‘held for no longer than is necessary for the purposes for which they were obtained’,17 meant that disposal of records had to be seriously considered. Records management as a systematic practice was becoming a necessity.

Electronic records

In March 1999 the government published its Modernising Government white paper.18 This visionary document set out the aim that all government departments should be capable of delivering 100 per cent of their public services electronically by 2008. To facilitate this, public institutions were instructed to take steps to ensure that all newly created public records could be stored and retrieved electronically. The National Archives (TNA) led work on this initiative. It published a ‘route map and milestones towards electronic records management by 2004’,19 which set out the steps institutions must take. These included:

![]() conducting an extensive audit of e-records

conducting an extensive audit of e-records

![]() compiling an inventory of those records

compiling an inventory of those records

![]() establishing appraisal and preservation plans for electronic records

establishing appraisal and preservation plans for electronic records

![]() developing a corporate electronic records management policy.

developing a corporate electronic records management policy.

All national museums and galleries were expected to comply. In short, this document forced the sector to consider the fact that most institutions had limited control over their paper record systems, let alone those in electronic format, and this was a daunting prospect. TNA was responsible for monitoring compliance. This was mostly done through a series of meetings organised by the sector’s client manager at TNA. Archivists (and where they existed, records managers) working in the national museums and galleries were invited to report back and share their experiences. As a result, most began to conduct basic e-record audits to identify what records were being created and determine their relationship with those in paper formats. Perhaps most significantly, nearly all started to work closely with their information technology (IT) colleagues.

At the time, TNA promoted the purchase and implementation of electronic document and records management systems. While many central government departments followed this route, these systems were prohibitively expensive for most national museums and galleries. Faced with implementing electronic records management with existing resources, many began to develop corporate file plans and structures: a key feature of good records management programmes. The impact of the Modernising Government agenda was significant: it prompted the sector to consider record keeping in its widest sense, encompassing records of all subjects and in all formats.

ISO 15489

The publication in 2001 of ‘International Standard ISO 15489-1:2001 Information and documentation – records management’ was an important event for the records management profession generally. It was developed in response to a consensus within the records management community to standardise international best practice. Establishing records as a business asset and focusing on the efficiencies achieved by good records management, it provided a considerable driver for the discipline. It is supported by British Standard (BS) PD0025-2:2002 (effective records management, practical implementation of BS ISO 15489, published in 2002), which provides an accessible and practical guide to implementation and is particularly aimed at new or non-professional records managers. Within the museums and galleries sector these standards also helped establish records management as a distinct discipline, just as ISAD(G) had done for archives five years before.

Freedom of Information Act

The most significant event for records management in the public sector, if not in the UK generally, was undoubtedly the passing of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in 2000. The Act applies to national, local authority and university museums. It gives individuals the right to access records held by public institutions. On receipt of a request, institutions have 20 working days to respond. The FOIA effectively replaces the 30-year rule, determining that records should be released to the public unless a specific exemption applies. For the first time, public institutions were legally required to provide access to their current and semi-current records. Those who did not or could not would be investigated by the Information Commissioner’s Office (the independent body charged with policing the Act). Institutions whose record-keeping practices were chaotic would find it very difficult to comply.

To prepare public institutions for the Act, the Lord Chancellor issued the Code of Practice on the Management of Records, laid before Parliament on 20 November 2002.20 Part One of the code is unequivocal: it states in section 5.1 ‘The records management function should be recognised as a specific corporate programme within an authority and should receive the necessary levels or organisational support to ensure effectiveness’; and again in section 7.1, ‘a designated member of staff of appropriate seniority should have lead responsibility for records management within the authority’. The code goes on to outline the basic requirements for managing records creation, review, disposal and archival transfer. Public institutions could no longer avoid it: establishing a robust records management programme was not just common sense, it was mandatory.

The practical implications of the FOIA (and other legislation) are explored in a later chapter, but the deep impact of the Act and the Lord Chancellor’s Code of Practice on records management in the museum and galleries sector cannot be overestimated. The code was updated in 2009; the new version (containing, for example, a section headed ‘The importance of records management’) is even more explicit in advocating the need for good record keeping. A recent survey of ten major national museums and galleries revealed that in 2000 only one employed a records manager; in 2010 seven of the ten had such a post on the payroll.21 Indeed, the last decade has seen extraordinary developments in the sector: when first introduced, most records management posts were established reluctantly and on a temporary basis. At best they were seen as short-term get-the-job-done project posts, brought in to conduct a one-time survey of record keeping in the institution, establish best practice and ensure compliance with the Act, after which it was thought they would be redundant. At worst they were instigated with the vaguest of remits, simply to ‘tick the FOIA box’ and deal with the mess. In both cases, museums and galleries were initially unwilling to make a significant investment in records management.

But records managers have begun to prove their worth. Of the ten institutions surveyed, five records management roles in the national museum and gallery sector are now permanent posts (it should be noted that some of these roles are of a dual nature, with responsibility for the institutional archive record). In addition to conducting record surveys, establishing best practice and helping ensure compliance with the FOIA, they are now actively involved in a wealth of activities including managing electronic records and addressing digital sustainability issues.

Significantly, there is a growing understanding of the relationship between records management and the institutional archive. Museum and gallery records are increasingly managed in a seamless fashion, from creation to destruction or transfer to the archive. Archives themselves are regularly exploited as a resource to celebrate anniversaries and promote brand identity in addition to their research function. Most national museums and galleries have now produced institutional histories based on material in the archive. Many have also published texts focusing on particular aspects of that history: archive records do not just tell us about the institution, they help to understand broader questions of social and cultural history. Museums and galleries have long been interested in the archival record; most now recognise that if they want to hold an archive that properly reflects their institutional history, it is vital to have a robust records management programme.

The value of records management in supporting core business is also increasingly acknowledged. Keeping good records informs decision-making and promotes efficiencies, and records managers are emerging as information specialists – a valuable commodity in the museum environment. This is demonstrated by the fact that four out of the seven records management posts noted earlier are located in the directorial/ strategic, rather than research, area of the institution. The impact of the FOIA is far from diminishing; requests received each year are increasing and the resulting transparency in business is slowly filtering through to private institutions. The public now expect openness, regardless of an institution’s status.

Records managers themselves have been proactive in developing best practice and promoting excellence in the sector. In 2004 representatives from the National Portrait Gallery, the Tate and the Imperial War Museum produced a generic file plan for museums and galleries. In 2007 an electronic records management working group was formed to discuss issues relevant to museums and galleries and investigate the potential benefits of collaboration.

Through initiatives like the Renaissance London Museum Hub’s Information and Records Management Project (started in 2007, and continuing at the time of writing), experience at the national level is further developed, refined and disseminated to non-national and regional museums.22 The Hub project has been responsible for promoting good practice via guidance materials and training workshops. Although the materials were produced for museums in the London region, they are freely available to any institution.

Work also continues with archive-related guidance materials. In 2006 the Archives in Museums Specialist Skills Network was established. Continuing the work of SCAM, it seeks to support and help those looking after archives within museums. It is open to all and resources are free to download via the Collections Link website.23

The last ten years have seen remarkable change: in 2000 museum records management was practically non-existent; now it is a recognised and growing discipline at the national museum and gallery level. For all this progress, however, there is still much work to do. Establishing and maintaining a records management programme in even a moderate-sized institution represent an enormous amount of work, and most museums and galleries are still under-resourced in this area. The roles of archivist and records manager are frequently shared by one post. Although this situation supports the seamless management of records (from creation to destruction or maintenance as an archival record) and is particularly welcome in a museum environment where many core record series (such as object files) are permanently active,24 this amalgamation of the two disciplines frequently means that neither gets the full attention it deserves. In addition, although sector-specific guidance is beginning to emerge, there is still a great deal to be done before best practice is fully implemented. Electronic records remain an enormous challenge (not just in the museum and gallery sector), but provide an imperative for records management whereby issues regarding obsolescence demand that the sector takes steps now to secure its archives for the future.

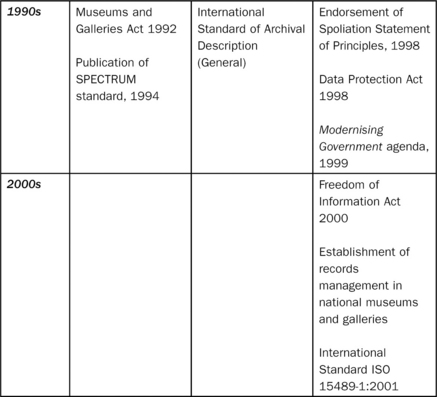

Record keeping in museums: roles

Record keeping in the museum environment has a long and complex history (Figure 1.1). It has often been viewed as the preserve of particular staff or section(s) of the institution, and the usual focus has been on records related to objects or those of archival nature. These traditions have left a legacy: the scope of the records manager’s role is frequently misunderstood. Re-educating an institution accordingly is a significant and important task. To do so effectively, it is necessary to have a clear understanding of the roles and responsibilities common in a museum environment.

While almost everyone in museums has some recordkeeping duties, a number of roles have significant responsibilities attached. In small institutions these roles may be distilled into one job. In others they may be undertaken by different staff. In both cases understanding the various approaches to record keeping and identifying the (sometimes subtle) differences between the requirements of each are vital if the records management programme is to be successful.

Records manager

Records management is concerned with managing records from creation to disposal. Traditionally, records managers are responsible for developing and implementing policies and procedures that help manage the daily creation, use and disposal of active and inactive records across the museum. They are concerned with the records produced by staff in the course of their everyday business; the material which is created daily in paper and electronic formats across the museum. Increasingly, this involves working with IT departments or third-party providers to manage e-mail systems and shared drives, as well as social networking (e.g. Web 2.0) applications and website content. When these records have reached the end of their ‘life cycle’, those identified as having permanent value are transferred to the archive.

Archivist

An archivist is concerned with managing records that have been identified for permanent retention because they have value to future generations. Archival management comprises the accession,25 processing, cataloguing and research use of and access to records designated as having permanent value to the museum. Archivists also conduct research on the history of the museum and ensure that material continues to be added to the archive, via internal transfer from its records management programme and/or donations from former staff or others. Some museums can afford to purchase museum records that may have left the museum and appear on the market, but most rely on donations from families of former staff to regain items that have inadvertently walked out of the doors. Museum archivists may be responsible for the institution’s own archival records, and/or archive material created by and acquired from external sources. This material is sometimes called ‘collected archives’ or ‘special collections’ (see below for a detailed explanation). In some institutions the roles of records manager and archivist are held by different individuals, but in many they are amalgamated into one post.

Registrar/collections manager

Registrars are responsible for asserting intellectual and physical control over objects entering and leaving the museum. They oversee and document the acquisition, accession and disposal of museum objects and do the same for loans in and out of the museum. In museums without registrars, curators are often responsible for registration functions. Depending on the museum’s policy, registrars may also accession special collections, or collected archives of other institutions or individuals that come into the institution’s physical custody. Accession files, accession registers, object files (sometimes called control files or case files), loans records and collections databases are often maintained by registrars.

Documentation officer

Larger museums may have the luxury of documentation officers, in charge of maintaining and administering collections databases and/or object files. Documentation officers are responsible for ensuring that object information is recorded according to external and internal standards across the entire museum. They may conduct object inventories and ensure that location information in databases is current, and help to develop and apply data standards.

Curator

Curators often carry out a huge range of tasks. Besides researching collections and developing exhibitions, they may also act as registrar, collections manager and/or documentation officer. Some curators are responsible for keeping object and loans files as well as accession registers. Even in large museums, curators often add information to collections management databases as they research object provenance or special subject areas. Curators may also create and keep exhibition files which may later end up in museum archives. They respond to vast numbers of external enquiries about museum collections and objects, and work with press and marketing officers to publicise the museum’s exhibits and holdings. Where there is no registrar, curators are often responsible for documenting object loans in and out of the museum.

Information manager

Information managers coordinate information policy and procedure (and sometimes the appropriate staff) across the museum. They ensure that the museum has a consistent and strategic approach to managing and leveraging its myriad information assets, in both electronic and manual (paper) formats. Records management and archives functions often fall under the broader umbrella of information management, as do documentation, registration and special collections.

Record keeping in museums: record types

Museum and gallery records are regularly managed as, or at least perceived as belonging to, the following groups (Figure 1.2).

Collections management records

Collections management records are also called collections documentation records. As discussed earlier in this chapter, record keeping in a museum environment has historically focused on the object. Museum staff have long recognised the value of object-related records. These may include accession correspondence and registers used to document the museum’s acquisition process. They also include records relating to individual objects themselves and may encompass documentation produced by the activities of acquisition, research, conservation, loan and display. These records may be filed together in an object file or by accession group, or can equally be maintained as a number of separate series.

These records have a high status within the institution. For national museums, this may be concerned with the fact that they have a statutory duty to maintain them as set out in the Museums and Galleries Act 1992. However, this heightened status is not a new phenomenon; object files have long been considered important both because they directly document the collection and because they are created and used by curators, traditionally the most senior staff in the museum environment.

For all museums, these records should be classified as vital because they are ‘mission critical’: necessary for the successful running of the institution. It is important that vital records are clearly identified in business continuity and emergency plans to ensure they are protected and prioritised for salvage in the worst-case scenario. Unlike other records, object records do not have an ‘expiry’ date: they are created and then remain in constant use for as long as the object remains in the collection (which, in most cases, will be for the life of the institution) or until (and even after) it has been deaccessioned. To explain further, they do not move through the stages of the record life cycle in the manner described in Chapter 2. They are created and remain ‘active’ for the whole of their life. Perhaps most crucially, they have immediate archival status; their value to future generations is recognised at the time of original receipt or creation.

As a result of all the above, collections management records have historically benefited from better management than other museum records. As explored earlier, a great deal of practical guidance exists for collection records (not least SPECTRUM), and the curator, registrar or collections manager post is dedicated in part to ensuring that object records are created and managed effectively. For all of these reasons, collections management records are often seen to exist separately from the rest of the museum’s records.

This idea is misleading for records management purposes. Object and collections management/documentation records are no different from any other museum records; they have been created by the museum in the course of its normal business and should be incorporated in the records management programme. This is important, because as ‘mission critical’ records they must be included in any institution-wide record-keeping initiative, and the rules documenting their management must be clearly established and understood by all staff. Including collections management records in a museum records management programme also allows them to be seen in their widest context, along with all the other records created by the institution – a principle which is at the heart of good archival practice concerning provenance.

General business, operational or administrative records

This group comprises the bulk of records created by a museum or gallery. It includes records concerning the following areas of activity.

![]() Organising exhibitions – can include records produced in the course of developing exhibition proposals, borrowing objects for display, managing exhibition spaces, etc.

Organising exhibitions – can include records produced in the course of developing exhibition proposals, borrowing objects for display, managing exhibition spaces, etc.

![]() Facilitating learning and access – can include records produced in the course of developing education programmes, organising lectures and workshops, compiling online learning resources, etc.

Facilitating learning and access – can include records produced in the course of developing education programmes, organising lectures and workshops, compiling online learning resources, etc.

![]() Governing the museum – can include records produced in the course of managing the high-level business of the institution, liaising with governing bodies, developing policy and strategy, etc.

Governing the museum – can include records produced in the course of managing the high-level business of the institution, liaising with governing bodies, developing policy and strategy, etc.

![]() Managing commercial activities – can include records produced in the course of hiring the institution as a venue, licensing its assets, producing publications, etc.

Managing commercial activities – can include records produced in the course of hiring the institution as a venue, licensing its assets, producing publications, etc.

![]() Developing external relationships – can include records produced in the course of liaising with the press, developing corporate and individual membership, enhancing community relations, etc.

Developing external relationships – can include records produced in the course of liaising with the press, developing corporate and individual membership, enhancing community relations, etc.

![]() Managing resources – can include records produced in the course of managing the institution’s staff, buildings and grounds, finance, etc., as well as managing information more broadly.

Managing resources – can include records produced in the course of managing the institution’s staff, buildings and grounds, finance, etc., as well as managing information more broadly.

Institutional archive

This group of material comprises the records received and created by the institution, from all areas of activity, selected for long-term or permanent preservation because they have ongoing historical value. A good records management programme identifies archival material and ensures records are transferred to the institutional archive at the appropriate time. The institutional archive is the final and lasting outcome of a good records management programme. Depending on the size and available resources of the institution, the records manager may also be responsible for the archive and vice versa.

Key record series likely to become part of a museum or gallery’s institutional archive include:

![]() minutes and papers of the museum’s board of trustees

minutes and papers of the museum’s board of trustees

![]() minutes and papers of other significant committees

minutes and papers of other significant committees

![]() object files (including acquisition and conservation records)

object files (including acquisition and conservation records)

![]() research subject files (including correspondence and research notes)

research subject files (including correspondence and research notes)

It is worth noting that in a museum environment (particularly where an archive or records management programme has yet to be introduced), the term ‘archive’ is sometimes applied to compiled histories of the institution (records that have been created or specifically brought together to form an institutional history). Often these records are bound in volume or scrapbook form, and may focus on particularly interesting episodes such as a history of the museum during the Second World War. Although these records may be fascinating, and should undoubtedly form part of the institutional archive, they are not the institutional archive itself. They represent a cherry-picked narrative and cannot replace the value of records viewed in their integral context. A true institutional archive preserves records in their original context and allows users to compile their own history. (It is worth bearing in mind that some staff may not appreciate this distinction.)

Institutional archives, although often perceived by the museum as being very separate, are part of the institution’s record. They must therefore be considered part of an integrated records management and archive programme, even if more than one staff member or different teams manage these activities.

There are also two groups of records, detailed below, likely to be held by a museum or gallery that are not part of the institutional record.

Special collections

Special collections (sometimes called collected papers or collected archives) include any records created by and acquired from external sources, usually because they support or add value to the institution’s main collection.

For example, the Archive of the National Portrait Gallery acquires the papers of portrait artists because these inform an understanding of both the portraits themselves and research into portraiture more generally. Whatever the subject matter and whatever the method of acquisition – donation, gift, purchase or bequest – the key difference is that these records have been acquired from outside the institution and, perhaps more crucially, were not created by the institution in the course of its daily business.

The Museum of London holds two collected archives: the Port and River Archive (including the records of the Port of London Authority) and the Sainsbury Archive (records of the supermarket chain). These archives document the activities of two external organisations, and are held by the Museum of London as collections in their own right – part of the history of London that the museum exists to document and interpret. For these reasons, they are not part of the museum’s records management programme.

There may be instances where records have been acquired from external sources but still form part of the institutional archive. For example, in previous years the distinction between the private and working papers of senior staff such as museum directors was often blurred, and as a result these records were frequently taken off site. Museums may later acquire such records posthumously from family members, and these materials should then be added to the institutional archive.

So it is the creator and context of the record rather than the source of acquisition that determines whether the material is part of the museum record. Therefore, special collections should not be considered part of a records management programme (although the records that document the administration of a special collection will fall under the records management programme).

The object collection

The object collection can include material in any format: paintings, scientific instruments or specimens, photographs, historical and archaeological artefacts and indeed documentary material such as film. The collection comprises whatever the museum collects, preserves, interprets and presents to the public. Many museums also acquire documents for their collections. In these cases, the records are accessioned objects in themselves and should not fall under the records management programme. In many museums, collected objects such as books may overlap with or are managed as part of library collections.

Managing documents as objects is perfectly acceptable if this is how they have been acquired. However, a common practice in some institutions is to transfer museum records into the collection once they are identified as being of particular interest. For example, the National Portrait Gallery’s institutional archive contains a series of photographs of staff and other individuals (such as trustees) created in the course of daily gallery business. Some of these feature famous or noteworthy personalities, and the temptation in the past has been for museum staff to remove these from their records series and catalogue them as single items for the collection. This is undesirable. If the record forms part of the museum’s institutional record – it was created as a by-product of the everyday activity of the institution, rather than specifically commissioned or acquired for the object collection – it should not be transferred to the collection.

This material must remain with unbroken provenance, in context – that is, among the other records created by the institution – in order to be fully understood. If an institution manages its records appropriately the material should be accessible no matter who is responsible for it or where it is stored.

The overall picture

So, museums and galleries keep records of all types or formats, in a variety of contexts and according to different management regimes. This can be confusing – what distinguishes one record from the next, and which should be included in a records management programme? Crucial to this decision is the creator: if a record was created or received by the institution in the course of its everyday business, it should be incorporated in the records management programme. This includes records concerning the collection (object files, accession registers, etc.) as well as records from all other areas of museum business (exhibitions, press, education and so on).

The records manager, or person with records management responsibility, may not have physical custody of all these records or day-to-day responsibility for maintaining them, but that person must have responsibility for managing them on an intellectual level. This includes advising staff on how to organise and store records, helping to determine records’ final disposition or transfer to the archive and developing overarching policies to manage these activities. Records management should constitute a corporate, museum-wide view: it should encompass all records created by the institution, regardless of custodian, format or subject matter.

1.For example, the National Gallery in 1824, the V&A in 1852, the National Portrait Gallery in 1856, the National Gallery of Scotland in 1859, the Natural History Museum in 1881 and the National Gallery of British Art (now Tate) in 1897.

2.The full title is An Act for Encouraging the Establishment of Museums in Large Towns.

3.For dates of establishment see Taylor (1999: 100).

4.Museums and Galleries Act 1992, section 2(1)–(3).

5.In 2003 the Public Record Office merged with the Historical Manuscripts Commission to become The National Archives.

6.Local Government Act 1972, section 224.

7.In June 2010 the Society of Archivists merged with the National Council on Archives and the Association of Chief Archivists in Local Government to become the Archives and Records Association.

8.The four significant events are the endorsement of a statement of principles by 44 governments at the Washington Conference on Holocaust Assets, the Data Protection Act 1998, the Modernising Government agenda in 1999 and the Freedom of Information Act 2000.

9.Spo·li·a·tion: n.

(i) the seizing of things by force

(ii) the seizure or plundering of neutral ships at sea by a belligerent power in time of war

(iii) the alteration or destruction of a document so as to make it invalid or unusable as evidence.

Encarta World English Dictionary.

10.In 2005 the Museums and Galleries Commission became the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council. In 2010 the body was abolished: responsibility for museums and libraries was passed to the Arts Council England and responsibility for archives to TNA.

11.See www.culturalpropertyadvice.gov.uk/spoliation_reports (accessed: 1 April 2010).

16.Under the terms of the Act, personal data are defined as information which relates to a living individual who can be identified. Processing includes obtaining, holding, retrieving and altering data. The definition is very wide and therefore it is difficult to identify any data functions an organisation might carry out that would not be classed as processing.

17.Data Protection Act 1998, Schedule, Part I, Principle 5.

18.See http://archive.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/moderngov/download/modgov.pdf (accessed: 1 April 2010).

19.See http://pdfdatabase.com/download/public-record-office-routemap-and-milestones-for-electronic-records-management-by-2004-pdf-15598557.html (accessed: 31 March 2010).

20.See www.justice.gov.uk/downloads/guidance/freedom-and-rights/foi-section-46-code-of-practice.pdf (accessed: 31 March 2010).

21.Unpublished survey by authors, April 2010.

22.The London Museums Hub is a consortium of regional museums funded by Renaissance London – the Museums, Libraries and Archives Council’s groundbreaking initiative to invest in and transform the country’s museums.

23.See www.collectionslink.org.uk (accessed: 31 March 2010).

24.Permanently active records are those that have been identified as having archival value but remain in everyday use by their creators.

25.For more information on the differences between accessioning objects into the museum and records into the archives, see Wythe (2004: 96–100).