Developing a file plan, retention schedule and records management programme

Abstract:

Explores how to develop and implement a file plan and record retention schedule in both electronic and paper environments. Examines the practical issues involved in using these tools to establish a records management programme.

Introduction

As established in Chapter 1, records management is a set of tools that enables museum staff to retrieve the right information in the right format at the right time at the lowest possible cost (Wythe, 2004: 112). Subsequent chapters have explored the conceptual context and the background information required to help prepare a records management programme. This chapter examines the key tools required to implement that programme: the file plan and records retention schedule. It also examines an important practical issue: how to approach the physical management of records. For the most part, the advice in this chapter is relevant to both paper and electronic records. However, in some instances the different formats have distinct requirements. Where this is the case, format-specific guidance is provided.

In addition, this chapter focuses on delivering electronic records management via a shared drive or network. This is not the only means of securing control over e-records: electronic document and records management systems (EDRMS) provide an alternative. EDRMS are databases designed to support the creation, management and delivery of electronic content, documents and records. However, not only are these systems usually expensive, they are also more suited to large-scale operations in which rigid corporate record-keeping rules can be applied. The working procedures needed to support such systems are generally over-complex for most museums. It is also now widely recognised that the principles and practices which must be developed and implemented to secure management of electronic records via a shared drive are relevant to the introduction of EDRMS. Specifically, any institution wanting to gain control over its electronic records – regardless of the operating environment employed to facilitate this – must develop and implement a corporate file plan and best practice guidance for naming records and version control. The advice in this chapter is thus relevant to all electronic environments.

The file plan

The file plan is not a new records management concept. Before the advent of mass computerisation, it was the key tool employed to help organise paper records. Traditionally, the file plan identified the different functional sections of an organisation and, underneath these functions, listed the major types, or series, of records created and held. Essentially, it was intended as a guide for filing. By grouping similar types of information together according to the main business functions and activities of the institution, records were easier to find. The file plan also established records as a corporate resource with all staff (at least in theory) filing and retrieving records from a single shared system. In some institutions, file plans were quite formal, often operating and known as ‘registered filing systems’. In others they were less official, with staff adding records to recognised but not rigidly observed structures.

Over the last 20 years, however, as computers became common in the workplace, file plans lost favour and individual record-keeping practices proliferated. It is only relatively recently that their value has been rediscovered. Without a recognised filing structure in place, the organisation of electronic records soon becomes chaotic. In fact, for this reason they are perhaps almost more useful in an electronic environment than they are for managing paper records. A file plan can help deal with the following common electronic record-keeping problems:

![]() increase of folders on the shared drive

increase of folders on the shared drive

![]() duplication of information (i.e. the same record held in many different folders)

duplication of information (i.e. the same record held in many different folders)

![]() chaotic filing structures (in which staff find it difficult to locate information of relevance).

chaotic filing structures (in which staff find it difficult to locate information of relevance).

In principle, a file plan for ‘born-digital’ records should look exactly the same as one for paper records and be employed consistently across both formats. The top level of the structure should reflect the museum’s main business functions. The subfolders underneath might include, at different levels, a combination of activities, team functions and record series. The file plan simply agrees these different groupings/folder titles with staff and thereby establishes a corporate structure into which all records can be filed.

In a paper environment, the file plan is primarily an intellectual construct used by the records manager to help establish a corporate view of the many record series created and managed by an institution. It may not necessarily ‘exist’ in a single identifiable form, but will be represented in the various tools (including retention schedules, best practice documents and so on) employed by the records manager. Although it might be desirable for individual staff to understand the entire filing structure of their institution, this is not always necessary in practice. In larger institutions, which encompass many functions and produce hundreds of record series, staff ultimately need only an awareness of how to manage the records for which they are responsible.

However, in an electronic environment the situation is different. Many institutions now manage records via a ‘shared drive’; where this is the case, staff are normally presented with a view of the entire network structure (represented by folders and subfolders) of the organisation and required to determine where to file their records within it. Although it is possible to block folders from view or provide staff with shortcuts to relevant areas, this becomes time-consuming and problematic as settings continually need to be updated when staff leave or take on new tasks. In an electronic environment, it is therefore vital that staff have an understanding of the corporate structure: how the records they create fit into the whole. This will enable them not only to file electronic records appropriately, but also to navigate the shared drive to locate and retrieve records of relevance. This is most important if the communal working facilities of the shared drive – specifically, the ability to share records readily (a facility not available in the same way in a paper environment) – are to be maximised. Unlike the paper environment, when creating an electronic document staff need to consider ‘How does this record fit into the whole?’ This represents an enormous culture change: in an electronic environment, all record creators must also become to some extent record keepers.

For this reason, a recognised file plan is the key to successful management of electronic records. Constructing and implementing a file plan suitable for twenty-first-century business practices incorporating both paper and electronic records can be a complex exercise, not least because it requires the involvement of staff across the entire organisation. The following steps are recommended.

Step 1: Background research

The first step is to review how paper records have historically been managed in the institution. Although it might appear that there is no formal structure in place, closer inspection could reveal that records have been organised according to particular types. If a record survey has been conducted, review the data collected – are there any patterns or groupings that emerge? If the museum employs an archivist, speak to them about how historic records have been arranged. Examine the archive catalogue, if there is one, to determine universal language and themes that might be applicable across current business. Above all, try and take the widest view. This will help determine the functions that the institution has consistently undertaken. It is important that the system developed is both future-proof and transparent.

Having examined the historic arrangement of the institution’s records, look at how they are currently organised. How does the museum manage its ‘born-digital’ records? Relevant information might have been identified during the record survey process if this encompassed shared-drive spaces. It will be useful to review this during the process of file plan development. The following questions should be considered.

![]() What does the top level of the shared drive say about the work the museum carries out; what common themes or groupings can be identified?

What does the top level of the shared drive say about the work the museum carries out; what common themes or groupings can be identified?

![]() What information is filed on the shared drive? How has this been arranged?

What information is filed on the shared drive? How has this been arranged?

Having established both how the institution managed its records historically and how it manages them currently, the two systems should be compared. Is it possible to determine any series groupings or patterns that are consistent across both? Even if on the surface it appears that records are unmanaged, on closer inspection it is likely that some type of order exists. Most record creators arrange their records according to their own kind of logic. It may be that only the very loosest of structures can be identified, but this is still relevant. It is important to avoid reinventing the wheel. Not only will this save a lot of work, but by basing the file plan on patterns that already exist across historic and current record arrangements, the structure developed will be both understood and used by staff. It is also more likely to be future-proof.

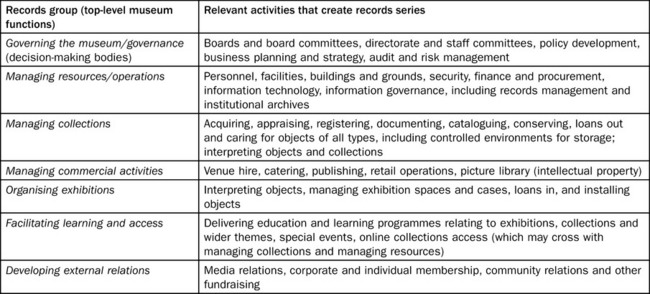

It is a good idea to look at file plans in other similar organisations.1Although there will always be differences, the core business of most museums and galleries is remarkably similar. Figure 7.1 suggests seven ‘top-level’ functions – or record groups – that are common in the sector.

Depending on the size of the institution, it may not be necessary to include all the top-level functions listed in Figure 7.1. Similarly, some functions will have more subsets of activities (and result in more records series) than others.

The activities or key records series listed reflect the work carried out by museum staff. While some activities concern a single functional area (e.g. Loans in records can only be found under the Organising exhibitions function), others relate to several records groups (e.g. most functions include policy creation). The question to answer from a records management point of view is whether it is appropriate for the shared drive to include a number of different policy folders, or whether the museum would benefit from a single ‘master file’ in which all these policies reside. If the latter is preferable, where should that master file live? The answer will probably be determined by which job role has ultimate responsibility for those policies – and if more than one role has responsibility, then those files might live outside the relevant team directories or folders. Other similar problem areas are likely to include finance records and best practice or procedural documents.

Chapter 8 contains further information on sample file plans.

Step 2: Consultation with colleagues

Once the record-keeping patterns and structures that already exist in the institution and the sector are determined, the task of developing the file plan can begin in earnest. There are two ways to approach this.

![]() Draft the new proposed structure independently (based on the review work carried out) and then consult with selected colleagues to agree the final plan.

Draft the new proposed structure independently (based on the review work carried out) and then consult with selected colleagues to agree the final plan.

![]() Conduct interactive workshop sessions in which the existing structure is reviewed and a file structure is drafted with selected museum staff or teams. The chosen approach will probably depend on the size of the organisation, the timeframe available and the number of staff on hand to assist with the work. If the workshop method is preferable, the following steps are recommended.

Conduct interactive workshop sessions in which the existing structure is reviewed and a file structure is drafted with selected museum staff or teams. The chosen approach will probably depend on the size of the organisation, the timeframe available and the number of staff on hand to assist with the work. If the workshop method is preferable, the following steps are recommended.

![]() Hold a preliminary session to ensure staff understand exactly what a file plan is and the benefits it can bring the institution.

Hold a preliminary session to ensure staff understand exactly what a file plan is and the benefits it can bring the institution.

![]() Organise a workshop session in which staff address the question ‘What does our institution do?’ All answers, from the grand (e.g. builds an understanding of national identity through portraits) to the small scale (e.g. serves tea in the cafe), are acceptable. Encourage staff to be open. Write the responses on ‘sticky notes’; when no further ideas are forthcoming, arrange the sticky notes into like groups. Ensure each group has a heading. While it is important the records manager or person facilitating the session is informed about sector-relevant file plans, do not circulate or discuss examples with colleagues beforehand.

Organise a workshop session in which staff address the question ‘What does our institution do?’ All answers, from the grand (e.g. builds an understanding of national identity through portraits) to the small scale (e.g. serves tea in the cafe), are acceptable. Encourage staff to be open. Write the responses on ‘sticky notes’; when no further ideas are forthcoming, arrange the sticky notes into like groups. Ensure each group has a heading. While it is important the records manager or person facilitating the session is informed about sector-relevant file plans, do not circulate or discuss examples with colleagues beforehand.

![]() Write up the sticky notes into a draft file plan and circulate to staff.

Write up the sticky notes into a draft file plan and circulate to staff.

Whether the file plan has been drafted independently or constructed with staff, allow plenty of time for feedback.

Step 3: Implementing the file plan

As discussed earlier, the file plan should remain consistent across all record formats. Although it may not ‘exist’ in a single identifiable form in a paper environment, in an electronic environment it is likely to be visible to all staff, as represented by the folders and subfolders of the shared drive. Consequently, while the ‘top levels’ of a paper file plan are largely intellectual constructs employed by the records manager, and therefore can be renamed or redesigned with little impact on staff, in an electronic environment quite the opposite is true. Staff across the institution will use the high levels of the file plan on a daily basis, and in order to ensure they can easily do so, various best practices have emerged.2 In an electronic environment the following are recommended.

![]() There should be a maximum of seven to ten folders at each level.

There should be a maximum of seven to ten folders at each level.

![]() There should be a maximum depth of four to five subfolders (‘clicks’) before the records themselves are reached.

There should be a maximum depth of four to five subfolders (‘clicks’) before the records themselves are reached.

![]() All records should reside at the same ‘level’ (number of clicks down).

All records should reside at the same ‘level’ (number of clicks down).

![]() Permissions should be ‘locked down’ for at least the first two levels (so that only agreed ‘super-users’ are able to add new folders). This is so that at these top levels the folder structure remains constant, enabling staff to become familiar with the route or file path they need to take to get to the records.

Permissions should be ‘locked down’ for at least the first two levels (so that only agreed ‘super-users’ are able to add new folders). This is so that at these top levels the folder structure remains constant, enabling staff to become familiar with the route or file path they need to take to get to the records.

The principles detailed above represent current best advice in the field of electronic records management. However, they are not absolute rules and some may be difficult to implement and sustain in a working environment. All file plans should be constructed in a manner that is sympathetic to the institution. For example, if the museum is small, it may not be necessary to introduce four or five folder levels. It is important to liaise closely with the IT department throughout the entire process. In particular, setting folder permissions is often guided by the specific network and systems parameters in an institution.

Before implementing the new structure it is important to determine whether it is appropriate to ‘close’ the existing structure and start again entirely from scratch, or to review the contents of the existing structure and attempt to rationalise and refile records retrospectively according to the best practice introduced.

The route taken will depend on the situation in the institution. If the shared drive is extensive and chaotic, it may be sensible to begin again. Working with the IT department, establish a ‘D-Day’ date from which point staff will no longer be able to add records to the old shared drive and all new business must be conducted in the new network space according to new best practice. In this instance active records – those required for everyday business – should be transferred over to the new structure. ‘Read-only’ access to the expired network space should remain (ensuring that staff can see the contents of the old shared drive, but not add to it).

If the museum is small, and the contents and order of the shared drive are relatively manageable, it may be preferable to rationalise and refile the contents. Reordering a shared- drive space might also tie in with the recommendations made in the initial record survey report. If this route is chosen, the following must be addressed.

![]() Duplicate records – does the network contain many copies of the same records? Does it contain folders with the same title? These records must be rationalised wherever possible.

Duplicate records – does the network contain many copies of the same records? Does it contain folders with the same title? These records must be rationalised wherever possible.

![]() Draft records – does the network contain drafts, notes or early versions of material later finalised? These are records that can usually be deleted.

Draft records – does the network contain drafts, notes or early versions of material later finalised? These are records that can usually be deleted.

![]() Expired records – does the network contain records which are no longer active (such as old minutes or reports). These records might be moved to cheaper near- line or offline storage (where they are not immediately visible to staff, but can be called back if necessary.) See below for a more detailed explanation.

Expired records – does the network contain records which are no longer active (such as old minutes or reports). These records might be moved to cheaper near- line or offline storage (where they are not immediately visible to staff, but can be called back if necessary.) See below for a more detailed explanation.

![]() Completed records – does the network contain records that can be ‘closed’ (folders for completed projects or other functions/activities) and made read-only for archive purposes?

Completed records – does the network contain records that can be ‘closed’ (folders for completed projects or other functions/activities) and made read-only for archive purposes?

![]() Reference records – if the institution has an intranet, it is useful to identify the records (usually policies and procedures) that staff need to refer to on a regular basis so that they can be made available on the intranet.

Reference records – if the institution has an intranet, it is useful to identify the records (usually policies and procedures) that staff need to refer to on a regular basis so that they can be made available on the intranet.

If rationalising an existing shared drive, records need to be moved and deleted as appropriate.

Step 4: Support through best practice and training

When the file structure has been finalised, it must be supported by guidance and training for staff. In a paper environment, this is relatively simple: staff need to know how to title and organise files pertinent to their area of work. Training can remain local and specific. In an electronic environment, it is of paramount importance that all staff adhere to the same practices. As such the following are essential.

![]() Naming conventions – what is the preferred method for titling folders and records?

Naming conventions – what is the preferred method for titling folders and records?

![]() Version control – what is the preferred method for managing drafts and different versions of documents?

Version control – what is the preferred method for managing drafts and different versions of documents?

![]() E-mail management – how will e-mail be managed? Should e-mails of significance be saved to the shared drive alongside other documents? If so, what format is most appropriate? Or are they best managed over the long term within the e-mail client server?

E-mail management – how will e-mail be managed? Should e-mails of significance be saved to the shared drive alongside other documents? If so, what format is most appropriate? Or are they best managed over the long term within the e-mail client server?

Without institution-wide agreed practice on the above, shared-drive spaces quickly become chaotic and opaque. An extensive literature in its own right has been written on this subject; since guidance is readily available, the issues are not discussed in detail here (although relevant resources can be found in Chapter 8).

When best practice documents have been developed, it is important to ensure they are understood by staff. Compulsory training sessions, organised with input from IT and personnel staff, present the best means of achieving this. A shared- drive file plan is only successful if all computer users understand how and where to create and save records.

Step 5: Consolidate and review

In a paper environment, the implementation of a file plan can usually be accomplished without much ado. Since staff ultimately need only an awareness of record series titles, and not the overall corporate scheme, the file plan can be introduced gradually, section by section, at a pace suitable to the institution. In the electronic environment, the implementation of a file plan represents a significant culture change. Regardless of whether the revised structure addresses only a small section of museum business or encompasses the entire shared drive, the likelihood is that the change from the old system to the new one will be managed as a ‘big bang’ event rather than a gradual shift in practices (bearing in mind IT protocols, permissions, network access, etc.). For this reason it is important to ensure that relevant staff (usually the records manager and IT personnel) are on hand and have time to answer any queries that arise, and that staff are aware that the structure is a ‘pilot’ and they should feed back any queries or problems so that changes can be made where relevant.

It may also be helpful to draw up simple procedures setting out:

![]() who has overall responsibility for the file plan

who has overall responsibility for the file plan

![]() who has permission to add folders at specified levels

who has permission to add folders at specified levels

![]() who is responsible for answering staff queries and making changes to the file plan in the longer term.

who is responsible for answering staff queries and making changes to the file plan in the longer term.

Bear in mind that developing a file plan is not a one-off activity. It represents the business and functions of the institution, so when these change the file plan must change too. This supports a principle repeatedly stressed throughout this text: introducing records management is not a project with a beginning and end. It is an ongoing requirement.

Finally, the records management policy should be amended so that it refers directly to the file plan and other best practice documents, and explicitly states that this is the museum’s preferred way of managing its records.

Developing and implementing a file plan is invariably a complex piece of work, especially because it requires a global view of the institution’s business and in an e- environment involves at some level all computer users. The process should not be rushed. There are no ‘correct’ answers and there will always be records that do not fit obviously into the categories that have been determined. In the context of a file plan, the ‘square peg in a round hole’ scenario is unavoidable. It is important to spend time developing the most user-friendly, transparent structure possible, but bear in mind that – at some point – staff will simply have to learn how to use it, just as they would any software employed by the institution.

Provided the file plan has been thoroughly planned, the benefits will be obvious. In a paper environment these will be realised primarily by the records manager: securing intellectual control over and a corporate view of the records of an institution is essential to the development of a successful records management programme. In an electronic environment, staff are the biggest beneficiaries and will quickly see the virtue of the changes. Agreeing a consistent structure and naming conventions represents good records management, because it allows everyone to access information they need quickly and easily. This will have immediate benefits for existing staff and should also secure a seamless transition and continuity for future post holders. Records created by predecessors will be readily available.

Remember, the foundation of the file plan already exists – it just needs to be moulded into a more consistent and workable structure.

The records retention schedule

Now that the file plan has been developed, work can begin on one of the most important records management tools: the records retention schedule. Indeed, all the procedures outlined up to this point lead to the preparation of this document. The records retention schedule is the blueprint by which an institution manages its records. It identifies every record series created by the institution and sets out:

![]() how long these records should be managed throughout the phases (active and inactive) of their life cycle

how long these records should be managed throughout the phases (active and inactive) of their life cycle

![]() what happens to records at the end of this process (review, destroy or transfer to the archive)

what happens to records at the end of this process (review, destroy or transfer to the archive)

![]() where they should be stored throughout this process (in offices, records store, servers, archive)

where they should be stored throughout this process (in offices, records store, servers, archive)

The process for developing the retention schedule can be accomplished as follows.

Step 1: Establish the structure

As mentioned earlier, the file plan should inform the retention schedule. Specifically, most schedules are organised or have the same layout as their related file plans. In particular, high- level functions or records series should be consistent across both documents. However, it is important to bear in mind that the record series listed in the schedule may not be exactly the same as the record groups in the file plan. The schedule may need to be more granular, because the length of time records are kept is influenced not only by business requirements but also by legislation and regulations, which can be very specific according to record type (for instance, within one series type, legislation may set out different retention periods for subsets of records). Figure 7.2 is an example of how an extract from a retention schedule might be organised.

In this example (with the possible exception of Registration), the record groups cut across departments or team functions. Organising the retention schedule according to the high-level functions identified in the file plan, rather than by department, establishes the document as a corporate resource which can be referred to by all colleagues. It also renders the retention schedule future-proof: restructuring and departmental name changes will not necessitate updates.

Depending on the nature and size of the museum, the retention schedule may be much more detailed than the file plan.

Step 2: Establish retention periods

The retention schedule addresses one of the most significant record-keeping problems faced by institutions: which records should be destroyed and when, and which records should be retained permanently. The retention periods set out in the schedule should be established in accordance with relevant legislation. Where legislation is not applicable, retention periods should be determined by weighing up the cost of retaining the records (i.e. physical storage space and back-up) against the cost of destroying them (i.e. the potential cost of a claim). The key Acts affecting record keeping are discussed in Chapter 4. These provide the foundation for retention decisions.

Developing a records retention schedule covering all the records created by an organisation may seem like a daunting task, but many of the functions carried out by the museum, such as activities related to finance, personnel, IT or health and safety, are generic to all businesses. Best practice schedules for relevant records are already available from a number of sources (see Chapter 8). This standard guidance will need to be adjusted to fit the idiosyncrasies and precise operating environment of the museum, but in general these parts of the schedule need not be compiled from scratch.

It is important to consult with colleagues throughout the process of developing a schedule. Even if legislation establishes that records do not need to be retained beyond a specified number of years, staff in the institution may have good reason for holding on to them beyond this point. Indeed, museums often retain records permanently that in another institution might be subject to scheduled destruction. This is largely because of their continuing value to the museum itself. As discussed in Chapter 3, although it is impossible to give precise figures, of all records created, museums tend to retain approximately 15 per cent permanently. The retention periods established should take into account both legal requirements and the particular business needs of the institution.

Step 3: Secure authority

When the schedule has been compiled and agreed with staff, the final and perhaps most important task is to ensure it has been ‘signed off’ by a senior member(s) of staff. The purpose of the schedule is to mitigate against risk (so that management of records is informed and appropriate). It also provides the records manager with the authority necessary to carry out the requirements of the role: to manage the records of the museum without constantly having refer back to the record creators. For this to be the case, the schedule must be approved by an appropriately senior staff member.

Neither the file plan nor the retention schedule is an inventory. A records inventory or file list is often useful for recording information about records that are inactive or archival (once they are not being amended or otherwise referred to on a regular basis). To summarise: the file plan is a document that sets out a framework for organising, or filing, the institution’s records. Staff should refer to it when adding folders or adding documents to folders, on the shared drive or in a paper environment. The retention schedule is a document that sets out how long categories of records (rather than individual documents, although there are some exceptions) should be kept, and what should happen to them when they are no longer active.

Implementing a records management programme

The file plan and retention schedule are the tools that sit at the heart of the records management programme. Now that these have been developed, consideration must be given to how the programme will be delivered in practice.

Establishing a records store

One option suitable for paper records is for the records manager or designated staff person to take physical custody of the records. What this means in practice is that records are physically transferred to a designated records store when they are no longer actively in use in offices by their creators or collectors. Records review and disposal are managed by the records manager, and until disposal records can be recalled by staff at any time (although once records are designated as having archival value, it is best practice for them not to circulate outside a reading room). Depending on the resources available, this practice can be implemented for all of the institution’s records or only selected records series. Which series are transferred may depend on a number of factors.

![]() Available storage space – offices that have very little space may have no choice but to transfer records when they are no longer active (not required for everyday business).

Available storage space – offices that have very little space may have no choice but to transfer records when they are no longer active (not required for everyday business).

![]() Value of records – a common practice is to ensure that only those records identified, or likely to be considered, for permanent preservation are transferred out of offices. This ensures that the records with the highest value are stored securely, and when the review period detailed in the retention schedule is reached, this process can be easily undertaken by records management staff.

Value of records – a common practice is to ensure that only those records identified, or likely to be considered, for permanent preservation are transferred out of offices. This ensures that the records with the highest value are stored securely, and when the review period detailed in the retention schedule is reached, this process can be easily undertaken by records management staff.

![]() Retention period – a common practice is to leave record series that have been assigned a disposal date (those that are definitely not required for permanent preservation) in offices. Since they simply need to be destroyed at an identified date, this process is easily managed by office staff acting in accordance with the retention schedule and/or in consultation with the records manager.

Retention period – a common practice is to leave record series that have been assigned a disposal date (those that are definitely not required for permanent preservation) in offices. Since they simply need to be destroyed at an identified date, this process is easily managed by office staff acting in accordance with the retention schedule and/or in consultation with the records manager.

![]() Records format – as already discussed, records exist in a wide variety of formats, but not all are suitable for physical transfer to a records management store. Electronic records are best managed within the working environment in which they were created. Unless the institution has considered and made provision for the medium- to long-term sustainability of electronic records, there is little point in accepting records saved to disk, USB sticks or other ‘fugitive’ storage devices. Likewise, records stored on digital media – CDs and DVDs – may be problematic if the institution has not planned how these records will be accessed over time. A common practice in many museums yet to develop comprehensive digital sustainability programmes is to operate a ‘hard copy only’ policy with regard to which records may be transferred to the records store. However, since the point beyond which it may not be practical to print out even selected hard copies is fast approaching, it is worth considering a digital sustainability plan when taking into account how to store records permanently.3

Records format – as already discussed, records exist in a wide variety of formats, but not all are suitable for physical transfer to a records management store. Electronic records are best managed within the working environment in which they were created. Unless the institution has considered and made provision for the medium- to long-term sustainability of electronic records, there is little point in accepting records saved to disk, USB sticks or other ‘fugitive’ storage devices. Likewise, records stored on digital media – CDs and DVDs – may be problematic if the institution has not planned how these records will be accessed over time. A common practice in many museums yet to develop comprehensive digital sustainability programmes is to operate a ‘hard copy only’ policy with regard to which records may be transferred to the records store. However, since the point beyond which it may not be practical to print out even selected hard copies is fast approaching, it is worth considering a digital sustainability plan when taking into account how to store records permanently.3

Most institutions operate a hybrid system that takes into account all of the above, but is also pragmatic. There will always be exceptions to the policy. In some cases, particularly if there is initial resistance to records management, it may be politic to take physical custody of records not normally destined for the records store in order to win goodwill and promote the records management programme. Likewise, if staff are particularly territorial, it may be pragmatic to leave records in their offices.

If there is uncertainty about whether it would be appropriate to establish a designated records store, the following factors should be considered.

![]() Space – is there enough available to establish a fully functional store? Remember that the store will need to accommodate not only those records already created and currently stored in offices, but those that will be created in the future. The volume of records transferred will increase exponentially usually for at least the first six years, when the first group of records reaches its review period,4 and often beyond this, as the records management programme develops. Before establishing a store it is a good idea to calculate the estimated annual record growth. This should be relatively straightforward if the records survey has been conducted effectively: identify the record series that will be transferred and determine the volume of records created each year. Remember to take into account that future records may be kept solely in electronic format.

Space – is there enough available to establish a fully functional store? Remember that the store will need to accommodate not only those records already created and currently stored in offices, but those that will be created in the future. The volume of records transferred will increase exponentially usually for at least the first six years, when the first group of records reaches its review period,4 and often beyond this, as the records management programme develops. Before establishing a store it is a good idea to calculate the estimated annual record growth. This should be relatively straightforward if the records survey has been conducted effectively: identify the record series that will be transferred and determine the volume of records created each year. Remember to take into account that future records may be kept solely in electronic format.

![]() Staff – are there enough staff available to operate a records management store effectively and efficiently? Remember, the transfer of records is time-consuming: at the very least each box of material will need to be logged. Depending on the exact nature of the system implemented, it may be necessary to carry out some weeding and repackaging (more information on the practicalities of transferring material is given below).

Staff – are there enough staff available to operate a records management store effectively and efficiently? Remember, the transfer of records is time-consuming: at the very least each box of material will need to be logged. Depending on the exact nature of the system implemented, it may be necessary to carry out some weeding and repackaging (more information on the practicalities of transferring material is given below).

![]() Service level – establishing a records management store means establishing a retrieval service. If the records manager/management team takes custody of inactive records, these records still ‘belong’ to record creators until they reach their disposal review date. They will need to be retrieved on request. Are there enough staff available to operate this service? A pilot may establish how often retrieval requests tend to occur.

Service level – establishing a records management store means establishing a retrieval service. If the records manager/management team takes custody of inactive records, these records still ‘belong’ to record creators until they reach their disposal review date. They will need to be retrieved on request. Are there enough staff available to operate this service? A pilot may establish how often retrieval requests tend to occur.

Pre-transfer

If establishing a records management store is desirable, clear procedures must be established to facilitate the transfer process. It is crucial that record creators take an active role in this process, as described above.

Establishing procedures that require those staff transferring the records to assist with the process also helps emphasise that the records store is not a quick and easy dumping ground for any old material. Other factors to consider are listed below.

![]() Will material be weeded for duplicates and ephemera before transfer? If so, who will undertake this work – the records manager or the transferring office?

Will material be weeded for duplicates and ephemera before transfer? If so, who will undertake this work – the records manager or the transferring office?

![]() Will the material be repackaged (boxed) before transfer? To maximise space on shelves, most records stores house the material in uniform boxes of a consistent size. Who will be responsible for the required repackaging – the records manager or the transferring office? Who will provide these boxes?

Will the material be repackaged (boxed) before transfer? To maximise space on shelves, most records stores house the material in uniform boxes of a consistent size. Who will be responsible for the required repackaging – the records manager or the transferring office? Who will provide these boxes?

![]() Will the transferring office complete a ‘transfer sheet’ documenting the contents of the boxes? Or are well- labelled files adequate for the purposes of logging the material (see below for further details)?

Will the transferring office complete a ‘transfer sheet’ documenting the contents of the boxes? Or are well- labelled files adequate for the purposes of logging the material (see below for further details)?

![]() Will the transferring office label the outside of the boxes or will this be undertaken by the records manager post- transfer?

Will the transferring office label the outside of the boxes or will this be undertaken by the records manager post- transfer?

It is a good idea to compile a ‘best practice’ or ‘how to’ document summarising the preferred transfer procedure. This is time well spent, since it will enable the records manager to deflect unsuitable transfer requests easily. Sample transfer guidance and forms are available in Appendix 12.

Post-transfer

Once the records have been transferred into the custody of the records store, they still need to be managed. To do this effectively, they should be logged; key data about the material should be recorded. This is most effective when done electronically. Elaborate systems are not necessary: Excel-type spreadsheets or standard databases like Access are both quite adequate. If the institution has a well-established archive, it may already have purchased records management software that can be utilised. The most common archive cataloguing system in the UK, Axiell CALM, has a package (CALM Records) specifically designed for managing the physical transfer of inactive records. However, this kind of application is aimed at large institutions managing a significant volume of records, and may not necessarily be suitable for smaller institutions. Whatever system is selected, the key elements of information that must be recorded are as follows.

![]() Accession date – recording when the records were transferred. This is usually in the format YYYY/running number for a group of records.

Accession date – recording when the records were transferred. This is usually in the format YYYY/running number for a group of records.

![]() Unique box number – to facilitate retrieval (usually a running number).

Unique box number – to facilitate retrieval (usually a running number).

![]() Record series name – this should correspond to the retention schedule and file plan.

Record series name – this should correspond to the retention schedule and file plan.

![]() Box contents – what information is held in the box? If the entire contents concern the same subject, a box title alone might be sufficient (e.g. ‘Shop receipts 2010/11’). In most instances, however, it will be necessary to list folder titles. Record the correct level of detail needed to facilitate easy retrieval at a later date.

Box contents – what information is held in the box? If the entire contents concern the same subject, a box title alone might be sufficient (e.g. ‘Shop receipts 2010/11’). In most instances, however, it will be necessary to list folder titles. Record the correct level of detail needed to facilitate easy retrieval at a later date.

![]() Date of records – record the date span of the records in the box. This is normally in the format YYYY–YYYY.

Date of records – record the date span of the records in the box. This is normally in the format YYYY–YYYY.

![]() Transfer body – what office transferred the records?

Transfer body – what office transferred the records?

![]() Retention period – this should correspond to the retention schedule. For example, + 6 years (current year plus six years).

Retention period – this should correspond to the retention schedule. For example, + 6 years (current year plus six years).

![]() Action at the end of the retention period – review, destroy or transfer to archive.

Action at the end of the retention period – review, destroy or transfer to archive.

![]() Date of action – when will the records be reviewed, destroyed or transferred to the archive? In some applications, this date will be automatically generated by the system. In others, it may need to be calculated manually.

Date of action – when will the records be reviewed, destroyed or transferred to the archive? In some applications, this date will be automatically generated by the system. In others, it may need to be calculated manually.

![]() Action complete date – date when the action was carried out. Even if a record has been destroyed, it is useful to maintain a record of this. This type of data should never be deleted from the system.

Action complete date – date when the action was carried out. Even if a record has been destroyed, it is useful to maintain a record of this. This type of data should never be deleted from the system.

To ensure that adequate transfer information is being recorded, it is a good idea to consider how it may need to be manipulated at a later date. Alongside basic searches identifying material for retrieval, the following requests are likely to be useful.

Managing records without a designated store

If it is not feasible to establish a designated records store, it will be necessary to determine which staff will be responsible for managing each record series throughout the ‘life-cycle’ stages. Who will carry out the actions detailed in the retention schedule? Will destruction and review of records be carried out by the records manager, or by other staff? Whatever is determined, the answer should be clearly communicated to the relevant offices and staff, and detailed in the retention schedule.

Complex systems are not required to manage the intellectual custody of records. Creating the file plan and retention schedule as basic Word documents is perfectly adequate if this is the only tool to hand. This will not enable the more sophisticated level of control that can be achieved by database systems, but it does secure a basic searchable record of what types of records the institution is creating, where these are being maintained and so on.

Management of electronic records

The processes discussed above concern the physical management of paper records. Electronic records, which exist in a virtual environment, have very different requirements. They should be organised according to the structure established in the file plan, but how best to ensure that they are deleted, reviewed or transferred to the archive in accordance with the provisions of the schedule? There are no absolute answers to these questions, as management of e-records is an evolving discipline and the precise operating environment of the particular institution needs to be taken into account when determining appropriate procedures. The subject is complex and an extensive literature in its own right exists. For this reason, what follows is a very general summary of the key issues.

Deletion and review of e-records

If e-records have been organised effectively according to a well-considered file plan (into defined record series, grouped by year or by subject), it should be relatively easy to manage the deletion of those records identified for disposal at a set point. EDRMS can be configured to manage the process automatically. In a shared-drive environment, the task must be assigned to a role or roles. Depending on the size of the institution, this may be sensibly undertaken by the records manager where the institution is small, or liaison staff in each functional area in larger organisations where the management of processes can be hugely time-consuming for one individual.

Where deletion of e-records is a devolved responsibility, it is expedient to amend job descriptions accordingly. This will help emphasise the fact that management of e-records is a corporate responsibility, and that the process has time implications. Even in cases where deletion is managed by liaison staff, the records manager will still need to play a supervisory role, monitoring the network to check that the work is being carried out in a timely and appropriate fashion. In all cases, IT personnel should be involved: the deletion of e-records may not as straightforward as simply clicking the delete button.

Where the action assigned to a record series is ‘review’, the process should always be undertaken by records management staff, since they have the expertise to determine whether records are required for permanent preservation. This is true regardless of working environment or format (EDRMS, shared drive or paper). Again, if records have been organised effectively, the procedure should be relatively simple.

In both situations, thought will need to be given to whether it is appropriate to store records on the network throughout the semi-active period of the life cycle. Network storage is used for everyday business – it allows frequent, very rapid access to data. However, it is also expensive. Depending on the particular situation of the institution it may not be feasible to store all data online until it is deleted or transferred to an archive.

Instead, IT personnel often advocate moving data to offline or near-line storage. Offline storage involves transferring data to tape or offline disk where it can be retrieved if and when necessary. Near-line storage is an automated system whereby data can be stored on cartridges that can be retrieved from their physical location and loaded remotely by machine. This places data temporarily back online. The disadvantage of offline storage is that storing and retrieving data in this way can be inconvenient and increases the risk of data corruption or loss. Near-line storage is a quicker and more convenient solution (data can be retrieved in just a few seconds), but it is more expensive and may not be feasible in smaller institutions. It should be borne in mind, however, that in both scenarios the removal of data from online storage areas will result in an improved speed of performance for networked data.

Working with IT personnel and taking into account all of the above, the records manager will need to determine whether it is appropriate to retain all data on the network during their active and semi-active periods; or to retain active data on the network but transfer all, or selected, record series to near-line or offline storage when they reach the semi-active stage of the life cycle.

The situation is analogous to a paper environment in which records are stored in prime office space while in everyday use, but may be moved to cheaper off-site storage during the semi-active period of the life cycle. Whatever practices are determined, it is important to record details in the retention schedule.

Transfer to the archive

Alongside ‘destroy’ and ‘review’, the retention schedule includes a third option: transfer to archive. It is important to examine what this entails in the context of electronic records management. Paper records are vulnerable to physical compromise, but if stored appropriately can last for hundreds of years with limited intervention and still remain accessible. The situation in an electronic environment is very different. The preservation of electronic records creates issues from the outset. Problems of technological obsolescence, media fragility and authenticity, if not taken into account at the time of creation, will quickly render the record inaccessible. Securing the permanent preservation of records in this context is complex: it represents perhaps the most challenging issue ever to face the archive profession. An in-depth examination of the subject is not within the intended scope of this book. However, it is worth bearing in mind the following important facts.

![]() Be aware that the term ‘archiving’ when used in an IT environment has a completely different meaning to the term as understood by the archive profession. (Briefly, in IT terms ‘archiving’ simply refers to the offline storage of information – normally for back-up purposes. It is not concerned with securing the comprehensive preservation and accessibility of information over the long term.)

Be aware that the term ‘archiving’ when used in an IT environment has a completely different meaning to the term as understood by the archive profession. (Briefly, in IT terms ‘archiving’ simply refers to the offline storage of information – normally for back-up purposes. It is not concerned with securing the comprehensive preservation and accessibility of information over the long term.)

![]() Migration (transferring records from one generation of computer software to the next), replication (refreshing digital records by copying them on to new media) and emulation (developing archive emulators of software which allow the contents of e-records to be viewed in their original format) are all options for securing digital sustainability, but they require a great deal of consideration and detailed planning – from the point of record creation – to execute successfully.

Migration (transferring records from one generation of computer software to the next), replication (refreshing digital records by copying them on to new media) and emulation (developing archive emulators of software which allow the contents of e-records to be viewed in their original format) are all options for securing digital sustainability, but they require a great deal of consideration and detailed planning – from the point of record creation – to execute successfully.

![]() Some institutions still operate a ‘print-to-paper policy’ for archival records. However, advances in technology – the proliferation of e-mail, for instance – means this is fast becoming unrealistic, if not undesirable. In addition, some dynamic records (e.g. databases or CAD systems) cannot be adequately replicated in a paper environment. For these reasons, it is important to begin addressing the situation. This does not need to be on a grand scale: the first stage may simply involve raising awareness.

Some institutions still operate a ‘print-to-paper policy’ for archival records. However, advances in technology – the proliferation of e-mail, for instance – means this is fast becoming unrealistic, if not undesirable. In addition, some dynamic records (e.g. databases or CAD systems) cannot be adequately replicated in a paper environment. For these reasons, it is important to begin addressing the situation. This does not need to be on a grand scale: the first stage may simply involve raising awareness.

![]() The issues surrounding digital sustainability are unavoidable. As the amount of data increases, more and more core business is undertaken in an e-environment; as institutions embrace new technologies, the problem will only be compounded. There are relatively simple ways of reducing future problems; for example, ensuring the institution employs the minimum number of file formats necessary to support business and restricts data creation in non-recognised formats.

The issues surrounding digital sustainability are unavoidable. As the amount of data increases, more and more core business is undertaken in an e-environment; as institutions embrace new technologies, the problem will only be compounded. There are relatively simple ways of reducing future problems; for example, ensuring the institution employs the minimum number of file formats necessary to support business and restricts data creation in non-recognised formats.

The issues are undoubtedly complex, and while answers are unlikely to be readily forthcoming, the problems must not be ignored. For museums, which are often under-resourced and do not have the funds or staff required to develop comprehensive solutions, a sensible approach might involve developing a digital sustainability strategy/programme. This can include an investigation of the issues within the particular operating environment, identification of high-risk areas/records and establishment of possible steps forward. The process of compiling this document will raise awareness, promote understanding and help to ensure a consistent approach across all areas of business.

This chapter has explored how to develop the two essential tools that sit at the heart of records management: the file plan and records retention schedule. It has also examined how a programme might be realised in both paper and electronic environments. It is important to bear in mind, however, that records management is an organic discipline that should be continuously monitored and reviewed. Tools, policies and best practice procedures that have been put in place may need to be altered to reflect any changes in business practice. For records management to reap the rewards outlined – supporting business, managing risk, saving money and resources – it must always remain sensitive to the business needs of the museum.

A final word

The essential steps needed to establish a museum records management programme are as follows.

![]() Make a business case and obtain mandate.

Make a business case and obtain mandate.

![]() Develop policies and procedures (define responsibilities; integrate into larger context and initiatives via strategic planning; draft framework documents).

Develop policies and procedures (define responsibilities; integrate into larger context and initiatives via strategic planning; draft framework documents).

![]() Obtain the necessary resources (space, funds and staff).

Obtain the necessary resources (space, funds and staff).

![]() Communicate the programme (using a variety of forums and ‘quick wins’).

Communicate the programme (using a variety of forums and ‘quick wins’).

Some of this is an iterative process. For instance, if the resources to carry out a records survey are available early on, it can help to make the business case and give you a chance to do some ‘quick wins’ as soon as the records management issues are identified. The steps do not have to occur in the above order, but they must all be implemented at some point. Purchasing some supplies so as to carry out ‘quick wins’ may come first. Some policies and procedures will necessarily be drafted later on. Like records management itself, it is easier to carry out any initiative in a systematic way. We hope the steps outlined in this book provide a useful route map.

1.A generic file plan, based on an unpublished prototype for national museums, has been developed for non-nationals and can be found at www.museuminfo-records.org.uk/toolkits/RecordsManagement.pdf. (accessed: 31 December 2010).

2.See www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/managing-electronic-records-without-an-erms-publication-edition.pdf (accessed: 31 December 2010).

3.The National Archives has produced useful guidance about this subject; see www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/guidance/e.htm (accessed: 31 December 2010).

4.As discussed in Chapter 4, six years is a common retention period assigned to many records series due to UK regulatory requirements.