Private Participation in Energy Infrastructure in MENA Countries: A Global Perspective

Abstract

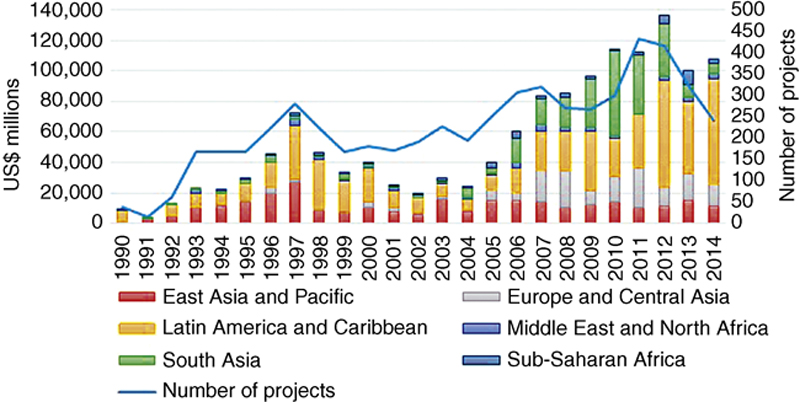

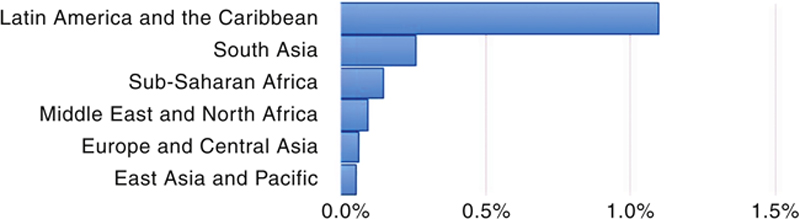

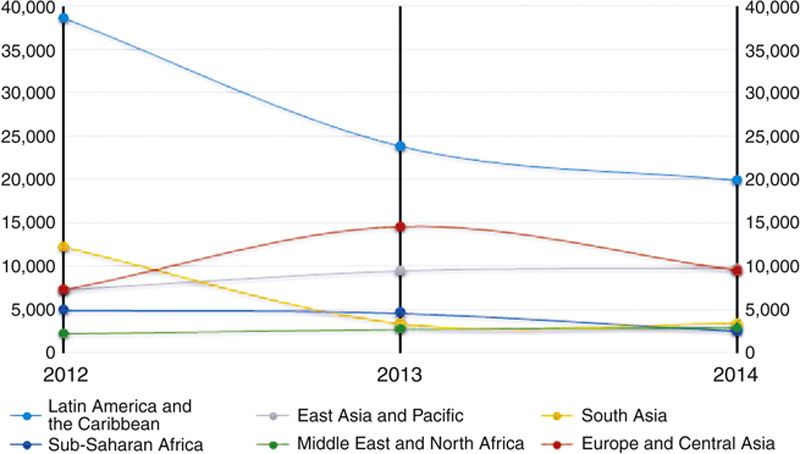

Investment in infrastructure, although historically dominated by public intervention, is experiencing a growing role via public and private partnerships (PPP). This trend traced a steady increase since the start of the privatization and liberalization process that took place in most OECD countries in the 1990s and peaked in 2012. While the study of the long list of factors that determine the attractiveness of an investment in energy infrastructure has been performed elsewhere in this book, we look at the emerging global trends in the energy, transport, and water and sewage sectors. We then narrow our overview to the energy sector, showing an interesting peculiarity both in terms of the relative regional attractiveness and the dynamics of the countries concerned. Finally, we explore the private participation in infrastructure (PPI) picture for energy investments in the Middle East and North African (MENA) countries, which are lagging behind both in relative and absolute terms. Moreover, the two countries that dominate the scene in the MENA region (Morocco and Jordan) are those that perform better in terms of a political stability score and rule of law score according to the World Bank. While further analysis will be necessary to define the relative impact of each enabling factor in the investment decision-making process, it appears evident that those two indicators are likely to determine the attractiveness of the market concerned for investment dominated by long lead times and irreversibility.

Keywords

1. Introduction

2. Global overview

Table 13.1

Investment Committed by Sector, 2014

| Sector | Number of projects | Average investment (US$ million) | Total investment (US$ million) | Total investment (%) |

| Energy | 157 | 30,613 | 48,063 | 45 |

| Transport | 49 | 112,802 | 55,273 | 51 |

| Water and sewerage | 33 | 12,424 | 4,100 | 4 |

| Total | 239 | 107,436 | 100 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on World Bank and PPIAF, PPI Project Database (http://ppi.worldbank.org accessed 07.11.2015).

Table 13.2

Investment Committed by Region, 2014

| No. | Region | Total investment (US$ million) | Total (%) |

| 1 | Latin America and the Caribbean | 69,113 | 64 |

| 2 | Europe and Central Asia | 14,254 | 13 |

| 3 | East Asia and Pacific | 11,514 | 11 |

| 4 | South Asia | 6,743 | 6 |

| 5 | Middle East and North Africa | 3,302 | 3 |

| 6 | Sub-Saharan Africa | 2,510 | 2 |

| Total | 107,436 | 100 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on World Bank and PPIAF, PPI Project Database (http://ppi.worldbank.org accessed 07.11.2015).

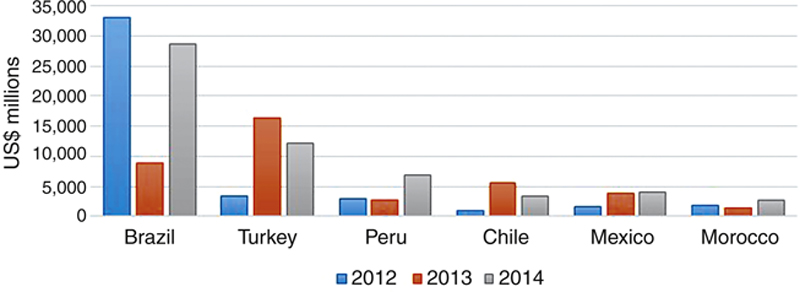

3. Energy investment

Table 13.3

Investment Committed by Country in the Energy Sector (2012–2014)

| Countries | 2012* | #2012 | 2013* | #2013 | 2014* | #2014 | Grand total* | Total* | Total (#) | Percentage of total |

| 1990–2014 | 2012–2014 | |||||||||

| Turkey | 2,223 | 11 | 13,246 | 20 | 7731 | 13 | 49,940 | 23,200 | 44 | 21.9 |

| Brazil | 19,312 | 34 | 220 | 35 | 2171 | 31 | 68,033 | 21,703 | 100 | 20.5 |

| Chile | 885 | 9 | 5092 | 13 | 3338 | 12 | 17,885 | 9315 | 34 | 8.8 |

| Thailand | 1,280 | 9 | 1251 | 12 | 3410 | 15 | 177,156 | 5941 | 36 | 5.6 |

| Morocco | 1,867 | 2 | 1438 | 1 | 2600 | 1 | 15,317 | 5905 | 4 | 5.6 |

| Mexico | 1,326 | 3 | 1179 | 10 | 2749 | 8 | 14,968 | 5254 | 21 | 5.0 |

| Grand total | 42,711 | 271 | 32.969 | 226 | 30,333 | 157 | 1,466,774 | 106,013 | 654 | 67.27 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on World Bank and PPIAF, PPI Project Database (http://ppi.worldbank.org accessed 07.11.2015).

* In US$ million.

4. Regional overview – the MENA region

Table 13.4

Investment Committed in the MENA Region by Country in the Energy Sector (2012–2014)

| 2012* | 2013* | 2014* | Grand total (1992–2014)* | Total (2012–2014)* | |

| Morocco | 1,867 | 1,438 | 2,600 | 13,017 | 5,905 |

| Jordan | 350 | 1,102 | 371 | 2,812 | 1,823 |

| Algeria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2,462 | 0 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,092 | 0 |

| Tunisia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 291 | 0 |

| Total MENA | 2,217 | 2,540 | 2,971 | 19,674 | 7,728 |

| Grand total (global PPI) | 42,710 | 32,969 | 28,643 | 1,224,927 | 104,322 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on World Bank and PPIAF, PPI Project Database (http://ppi.worldbank.org accessed 07.11.2015).

* In US$ million.

Table 13.5

Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism (2012–2014)

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| Morocco | 2.11 | 2.04 | 2.00 |

| Jordan | 1.98 | 1.98 | 1.88 |

| MENA average | 1.71 | ||

| Tunisia | 2.13 | 1.76 | 1.59 |

| Algeria | 1.14 | 1.18 | 1.33 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 1.05 | 1.04 | 0.88 |

Source: Authors’ elaboration from World Bank. WGI, Worldwide Global Indicators.

0, weak; 5, strong.

Table 13.6

Rule of Law (2012–2014)

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| Jordan | 2.76 | 2.87 | 2.89 |

| Tunisia | 2.37 | 2.35 | 2.30 |

| MENA average | 2.31 | ||

| Morocco | 2.28 | 2.29 | 2.25 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 2.10 | 2.04 | 1.90 |

| Algeria | 1.71 | 1.73 | 1.82 |

Source: Author’s elaboration from World Bank. WGI, Worldwide Global Indicators.

0, weak; 5, strong.

5. Conclusions

Percentile rank 0–100 indicates world ranking (0 corresponds to the lowest and 100 to the highest). Source: World Bank. WGI, Worldwide Global Indicators.