SEVEN

Deconstruct and Reconfigure Your Work

Using the Work-Automation Framework to Navigate Your Personal Work Evolution

Now you understand how the accelerating reinvention of jobs optimizes work automation. Our framework and examples show that it’s easy to get caught up in predictions about the end of human work, robots replacing humans, and sensors on every object that create big data. You have seen how cognitive automation can predict human behavior better and faster than any person and teach itself how to beat both human and computerized game players. A quick web search will easily unearth predictions such as a recent Fast Company article listing “the 10 jobs that will be replaced by robots,” including bank tellers, journalists, and movie stars.1 Or, a compelling graphic in Politico showing a future in which humans care for aging humans, while robots do everything else to move goods and information.

Our framework shows that automation will not replace people anytime soon. More realistically, the future will present constantly evolving combinations of human and automated workers. You can only see the patterns in that evolution through deconstruction, ROIP, and optimized work automation.

How should you prepare yourself? In this final chapter, we explain how to apply our “reinventing jobs” framework to your own work and career. The framework can help you identify more optimal goals for and approaches to your career and work.

The Perpetual Conversation about Agile Work and Reinvented Jobs

We’ve recommended, in chapter 6, that workers and leaders must have perpetual conversations about how their work is evolving so they can identify ways to upgrade work, reinvent jobs, optimize work automation, and balance human and automated work sources. The only way to keep up with the evolution is to have those conversations constantly. In that way, you are more likely to anticipate the evolution that affects you most, well in advance of a disruptive moment when automation replaces large parts of your job. Your conversations must include not only you, your leaders, and your fellow workers, but also your educational institutions and governments.

The reinventing jobs framework lets you have intelligent, nuanced, and productive conversations. You can get beyond the typical hyperbole about robots stealing human jobs and all workers becoming gig workers. You can now frame the conversation to focus on deconstructing jobs, describing ROIP, and reinventing jobs to optimize the combination of automation and human work.

Where can you start these conversations?

Sometimes your organization will provide the answer. In our previous book, Lead the Work, we described how IBM tackled these new work challenges by building a talent marketplace that deconstructs jobs into tasks and presents its workers with the tasks on a platform where they can volunteer and track their accomplishments. IBM’s approach entails deconstructing jobs and allowing workers to choose short-term projects. It also includes reinventing jobs by deciding what tasks to keep within a job. Reinvention encompasses permeable boundaries, with short-term assignments that sometimes exchange IBM employees with the employees of clients or partners. This internal talent marketplace not only encourages conversations about reinventing jobs, but requires them. IBM workers and managers must constantly work together to optimize the balance of tasks, regular jobs, and automation.

Sometimes the catalysts for the new conversations will emerge from educational institutions. Eloy Ortiz Oakley, chancellor of California Community Colleges, has noted experiments with alternatives to multiyear degrees. For example, portable and “stackable credentials” allow workers to cycle between learning and earning.2 They can take short courses to acquire credentials with immediate labor market value, return to work, and then come back to college for additional credentials. All the credentials along the way count toward certificates or degrees, and different combinations of credentials can be stacked to qualify for jobs or compile a certificate.

Sometimes, the catalyst for these conversations comes from nations and governments. For example, every nation is wrestling with the question of how to provide income continuity while workers are acquiring new skills or taking a break. One popular and controversial solution is universal basic income (UBI). A UBI in its purest form is a periodic cash payment to individuals that carries no means test or work requirement. It’s touted as a way to allow people to afford basic food and shelter, without requiring an organization to pay them. Workers would be free to pursue the work they enjoy or get qualified to jump to an entirely new profession. Finland launched a two-year experiment with UBI, selecting two thousand unemployed people to receive 560 euros per month (about one-fifth of average income).3

A variant on this theme is a hybrid of unemployment benefits and insurance, when workers receive income after automation displaces them to support their efforts to reinvent themselves. The Singapore government provides subsidies and a government-approved list of skills, encouraging workers to acquire the skills and companies to give their workers the necessary time off.4

Bill Gates has proposed “a tax on robots”—an employer who replaces a worker with a machine would pay taxes equal to those that the worker would have paid. The idea is to slow the pace of automation and create funding to give displaced workers the tools and opportunities to qualify for other work. The city of San Francisco was actively considering the idea in 2017.5

Organizations, educational institutions, and governments are important to a future work ecosystem that effectively adapts to the inevitable reinvention of jobs. Yet, they all rest on a foundation of workers and leaders like you. Every worker and leader has a role in the ongoing conversation, because they are on the front line. They will be the first to see the risks and opportunities of job reinvention. The faster and more alertly they detect them, and the more frequently and transparently they discuss them, the more likely that organizations and society will anticipate work upgrades early enough, and with enough sophistication, to avoid needless and wasteful disruption.

The reinventing jobs framework can guide those conversations.

Reinventing Jobs: A Personal Career Tool

The four-step process and framework can help you anticipate how your own work will evolve and prepare for it. Deconstruct your current and future jobs into work tasks. Then ask how the ROIP and automation are evolving. Where will automation substitute or augment your work? What can you do to reinvent yourself to better fit the tasks that will remain human?

Follow the four steps as they apply to your current and future work:

- Step one: Deconstruct your job. Key insights are revealed in the tasks within jobs.

- Step two: Assess ROIP. The payoff is the return on improved performance.

- Step three: Identify automation options. Choose from process automation, AI, and robotics.

- Step four: Optimize work. Find the right combination of deconstruction, ROIP, and automation.

Then, in the spirit of chapter 5, add:

- Step five: Navigate the organization. Find your place in a digital, agile, boundaryless work ecosystem.

Step One: Deconstruct Your Job

Deconstruct your job into its tasks and consider how each will evolve. To find your work tasks, start with your job description and its tasks, outcomes, and competencies. Also, consider how you actually do the work, particularly if that’s different from the formal job description. Describe the additional tasks and add them to your list.

Evaluate each work task against the three characteristics of work elements, to see which may evolve away from traditional employment or toward automation. Are the tasks:

- Repetitive or variable?

- Independent or interactive?

- Physical or mental?

The more repetitive, independent, and physical the task, the more likely it can already be automated or will be soon. Even mental work, if it’s independent and repetitive, can be automated by RPA and AI. Physical work will probably be automated by robotics.

Now, write the job description as it might appear in two, five, and ten years. Remove the tasks where automation will substitute for humans. Keep those tasks where automation will augment the work and consider how your work will change with augmentation. Finally, what tasks are humans likely to do for a long time? Which of those tasks are regular employees likely to do, and which might be done through arrangements other than employment?

Once you deconstruct and reinvent your job, you will probably find that your reinvented future job contains a fraction of the tasks that you do today. What work elements might be added to your job as it evolves (i.e., new work that will be created)? Can you reconstruct a job from the work that remains plus the new work? How does that align with your unique skills? Could you do some work through freelance platforms, gigs, contracts, or other engagement models either in your organization or elsewhere?

The Economist describes how future work will combine human workers, automation, and freelance work platforms:

For autonomous cars to recognise road signs and pedestrians, algorithms must be trained by feeding them lots of video showing both. That footage needs to be manually “tagged”, meaning that road signs and pedestrians have to be marked as such. This labelling already keeps thousands [of human workers] busy. Once an algorithm is put to work, humans must check whether it does a good job and give feedback to improve it. A service offered by CrowdFlower, a micro-task startup, is an example of what is called “human in the loop.” Digital workers classify e-mail queries from consumers, for instance, by content, sentiment and other criteria. These data are fed through an algorithm, which can handle most of the queries. But questions with no simple answer are again routed through humans.6

Step Two: Assess ROIP

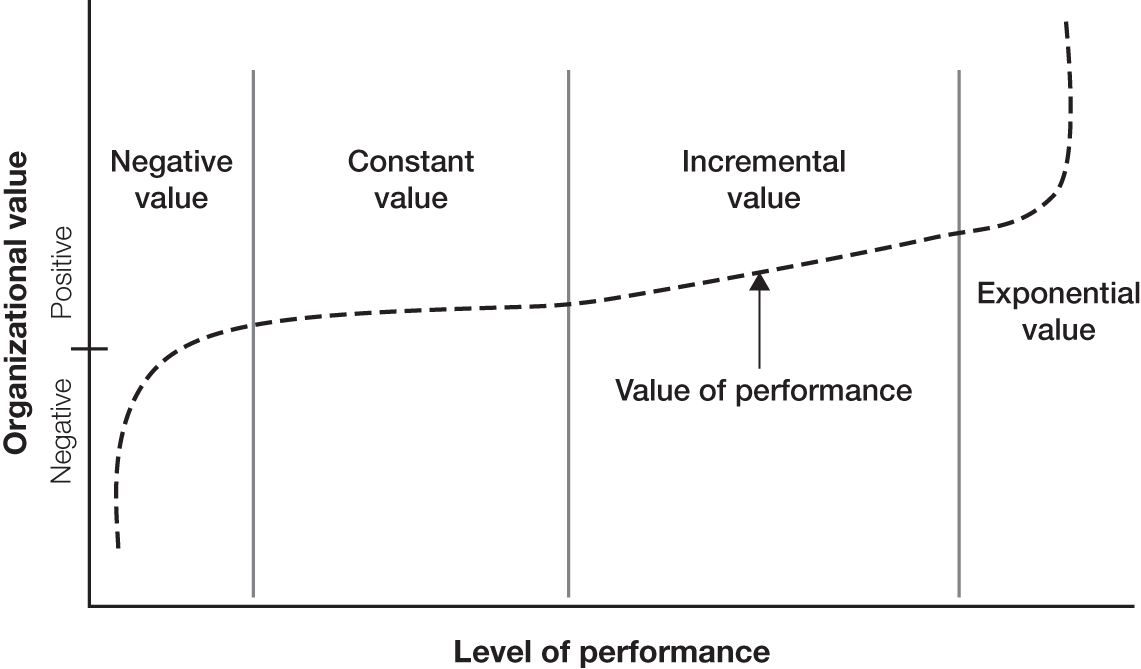

For each current and reinvented task, how does improved performance create value? The four ROIP curves we described in chapter 2 can help you map the payoff of the work. Figure 7-1 shows the four curves; the vertical axis is the value of performance, and the horizontal axis is the level of performance.

FIGURE 7-1

ROIP for a full range of potential work performance

You can often find clues to the ROIP of work tasks in discussions with your organization about your performance, key performance indicators, and so on. Conversations about performance, goals, rewards, and development often rely on a shared understanding about the tasks that make up the job, and how those different tasks pay off.

With ROIP identified, consider the implications for work and automation. For the tasks that add ROIP by avoiding mistakes, could robots, RPA, or cognitive automation better reduce human error? If the tasks with error risks are automated, might you be free to spend more time on the tasks that produce incremental value?

For the tasks where different performance approaches add very little value beyond a certain minimum standard, is it possible that AI could learn the best way to do the work? Or will AI help train or nudge workers toward a common way to perform? If you could expect this work to be done consistently, would that allow you to stop wasting time on unproductive variations?

For tasks that add incremental value, will automation help you move up and to the right on the ROIP curve? For example, if you add incremental value when you interact with customers, will automation improve your interactions by giving you better information about the customer? Will AI essentially make you and other workers equivalent to today’s top performers? Or, is your greatest value in training the AI on the most successful customer-interaction patterns?

Finally, for tasks that create exponential ROIP, how will automation create whole new kinds of work? For example, if your value is in understanding the subtleties of how equipment operates or how parts of a process integrate, then when automation takes on the tasks of operating the equipment or monitoring the process, will your new work occur in a cockpit, where you operate and diagnose whole arrays of machines and processes, just like the oil drillers we discussed earlier?

Step Three: Identify Automation Options

Now, consider the three types of automation (in chapter 3): RPA, cognitive automation, and social robotics. Determining which types of automation will apply to your work will help you understand the likely speed and consequences of automation for you. Remember that in most real situations, several types of automation will converge.

RPA applies best if your job has mental tasks with one or more of the three Rs: repetition, redundancy, and risk. RPA needs no programmed intelligence, so it is typically the cheapest, quickest, and easiest to apply. If your tasks are amenable to RPA, you can probably assume they will not be done by you or other humans.

Human workers and their union or other representatives often resist RPA, fearing that they will be displaced. That is a very real possibility. However, the long-term solution will seldom prevent the new technology. Rather, the optimum and most socially beneficial answer is likely to emerge as workers and leaders openly and regularly discuss the implications, and reinvent the jobs before humans are displaced. A recent Chicago Tribune article described a Wisconsin factory where robots don’t replace humans, but they fill in the gaps caused by worker shortages.7 On an assembly line intended for twelve workers, “two were no-shows. One had just been jailed for drug possession and violating probation. Three other spots were empty because the company hadn’t found anybody to do the work. That left six people on the line jumping from spot to spot, snapping parts into place and building metal containers by hand, too busy to look up.” Despite increases in wages and efforts to recruit qualified and stable workers, the shortage persisted.

RPA and social robots provided a win-win solution: “In earlier decades, companies would have responded to such a shortage by either giving up on expansion hopes or boosting wages until they filled their positions. But now, they had another option. Robots had become more affordable. No longer did machines require six-figure investments; they could be purchased for $30,000, or even leased at an hourly rate.” Supervisors explained that the robots would not take anyone’s job, but make up for jobs they couldn’t fill. One worker, reliably doing the job for years, tired of the constant turnover and empty work spaces that required her to work harder. When one employee said, “They are taking somebody’s job,” she replied “No, they are not . . . It’s not a good job for a person to have anyway.”8 Cognitive automation can do things like recognize patterns, understand language, and learn rules. Which of your tasks does these things? If the patterns are simple, the languages are well known, and the rules are fixed, then cognitive automation or AI may substitute for humans, or already has. The move to automation is even faster when cognitive automation can be combined with sensors, such as the cameras equipped with AI that know they are photographing.9

On the other hand, the more complex or obscure the patterns, languages, and rules of your task, the longer cognitive automation will take to master them. Indeed, in the interim between fully human and fully automated, the new human work is training the cognitive automation. Human riders train the AI that supports self-driving cars. Every time the human corrects the AI, the program learns. Perhaps your work will evolve from doing the task to training the AI to learn the task. Uber built a fake city in Pittsburgh, called Almono, populated entirely by self-driving cars. In the fake city, automation designers can simulate things that they can’t test in the real world, such as mannequins darting out front of vehicles. In addition to vehicle testing, an important goal is to train the human drivers who will eventually accompany the vehicles on actual roads: “The program that trains vehicle operators is rigorous. It takes three weeks to complete and requires trainees to pass multiple written assessments and road tests.”10

Of course, cognitive automation may soon teach itself. In October 2017, the AlphaGo Zero AI system achieved what some have called a “singularity” in which it learned to play the board game Go with no human interaction. Designers simply programmed the game with the rules and objectives, and then instructed it to play by itself, over and over, and very quickly. An earlier AlphaGo system had required programming with the past games human experts had played. That first system defeated a world champion player in March 2016. The new system, playing only by itself, beat the original AlphaGo.11 So, be alert to continuing evolution. Perhaps, in the near term, you will teach automation, like the original AlphaGo, but eventually automation like AlphaGo Zero will learn on its own, so you will need to reinvent again.

Social robotics involves robots that move and physically interact with humans. The robot Baxter is a cobot that literally works next to humans to do things like loading, machine tending, and materials handling. Fast Company described cobots that greet guests at the Henn na Hotel (translation “strange hotel”), and make coffee and clean rooms at the YOTEL New York; “Botlrs” at Starwood Hotels that use the elevator without assistance to deliver amenities to guests; an OSHbot at Lowe’s stores that locates items for customers, and an AI security guard called Bob.12 At the MIT Sloan School of Management, staff who are working from home can attend meetings, as a robot.

A Financial Times article points out the need for workers to constantly analyze how their jobs will be reinvented.13 It describes a facility with a traditional human-worker assembly line on one side and a cobot-enhanced line on the other:

On one side, the light is dim and workers stand at long assembly lines repeating the same task over and over. On the other, a fleet of low-lying robotic trucks scoot around the shop floor, restocking restyled workstations. In these small cells, a single employee helped by a robotic workbench assembles a virtually complete drive system that will be used to power the production of everything from cars to cola. Elsewhere, a robotic arm called Carmen helps workers load machines or pick components out of bins. Here, the light is brighter, and the workers say they are happier. “Everything is just where I need it. I don’t have to lift up the heavy parts,” says Jürgen Heidemann, who has worked there for 40 years, since he was 18. “This is more satisfying because I am making the whole system. I only did one part of the process in the old line.” Stéphane Maillard, a 13-year veteran aircraft assembler said the robot has not replaced his job. “It has changed the way of working . . . Before it was very manual. Now it is more about piloting the robot. 100 per cent of our operators would never go back.”14

Such low-cost cobots now allow small local factories that could not compete before to operate competitively and retain jobs for humans. Yet, the article also noted that many companies refused the reporter’s request to see their cobots in action, perhaps fearing adverse publicity. Tony Burke, assistant general secretary of the Unite union, noted that “job losses could be horrendous in some areas . . . but the problem is that nobody really knows.”15 The solution is not to deny the effects or to hide from the press. Progress will require difficult, candid, and open conversations about the specific effects of automation at the work-task level. The framework in this book can help define and guide those conversations, to move beyond simplistic questions focused on job losses to a more nuanced conversation about the optimal work-human combinations, with society, workers, unions, companies, and communities defining “optimal.”

Step Four: Optimize Work

The first three steps, applied to your work and the work of your colleagues, prepares you to have the right conversation about how the work will evolve and how to prepare for it. The key is to distinguish and integrate the elements of our framework: work tasks, ROIP, automation type, and automation role

John Donahoe, the CEO of ServiceNow, put it well: “There’s this assumption that it’s going to be people or robots, all or nothing. My experience is that it doesn’t operate that way. It’s automating part of the job, but not the full job. Repetitive, manual work—no one who’s doing it is really enjoying it. Technology replaces and creates. It replaces manual work and creates new opportunities—new tasks, if you will. And productivity creates growth, which creates new kinds of work. It is a virtuous cycle. It’s so easy to talk about it in binary terms. I just don’t think that’s the reality.”16

Step Five: Navigate the Organization

Figuring out how your tasks will evolve and how to reinvent your job is not the end of the conversation. Your work will exist in a larger organization that is also being reinvented. That organization will not be confined by the traditional boundaries, with employees inside doing the work and others outside waiting to join. Rather, the future organization will be a hub of work arrangements like the ones we discussed in the previous chapter: free agents, talent platforms, volunteers, alliances, outsourcing, robotics, and AI.

You must navigate this organization by finding the optimum way that your reinvented job fits and connects with those who are your clients and collaborators. Sometimes you will be a traditional employee, sometimes a freelancer on a platform, and sometimes you’ll take a tour of duty with an alliance partner, and so on.

You will face questions like these:

- What part of your future work should be kept in a traditional job?

- What proportion of future work should you pursue as a side gig through a work platform?

- What tasks will be substituted versus augmented by automation?

- How should you get the experiences and skills that will support your evolution?

- In what tasks and jobs should you become an expert, available to train AI or humans?

All the while, you must also be alert to the perpetual work upgrades that are the new reality of your work.

As a leader, you must create an environment where you collaborate with workers and other constituents to answer a parallel set of questions for your organization:

- What future work should be kept in a traditional job?

- What future work should come through gigs on a freelance platform?

- How should you give your workers the experiences and skills that will support their evolution (such as tours of duty, projects, social learning, etc.)?

- For what areas of work should you transform those that do the work to become the trainers of AI?

All the while, as a leader, you will also observe the perpetual work upgrades that are the new reality of your work. But, as a leader, you will also consider not just your work but related work and how to create the organization of the future.

The good news is that if organizations, nations, governments, and workers are empowered to work together, you are more likely to have the tools and structures you need. The new work ecosystem with constantly upgraded and reinvented jobs has the potential to empower workers, create boundless opportunities for careers and learning, and solve thorny issues of skill gaps and regional inequality. The bad news is that if workers and organizations navigate this new world in secret, without trust and transparency, then the work ecosystem risks being exploitive, opaque, and dysfunctional. That trust and transparency requires processes like “reinventing jobs” that offer a framework and language to candidly and clearly communicate about the coming evolution. (See the sidebar “Principles Guiding the Development and Use of AI.”)

As a leader, you can be a role model, supporting the conversations with opportunities, a framework, and the necessary information and safety net that empowers you and your workers to collaborate to optimize work automation. You can help your workers follow these steps. You can create a safe culture in which workers can tell you when they see the possibilities for automation to replace their tasks and where augmenting tasks with automation could significantly improve productivity. If workers think that such revelations will result in their dismissal or exploitation, they won’t share. If that happens, then you miss the chance for the productivity enhancements, and your workers miss the chance to evolve in advance. As challenging as the conversations will be, it is likely much more painful to make these transitions when everyone hides until forced to act.

Conclusion

As we consider the many rapid advancements in automation and work, remember that people are not powerless. The future of work is entirely up to us. Whether we use technology to substitute, augment, or create work is and should always be a conscious and informed choice.

In this book, we set out get beyond the hype to describe a concrete, actionable way you can understand and prepare for automation and its effects on work and jobs in your organization. Leaders everywhere are struggling with these hard questions. We hope that the tools provided here give you a more structured, nuanced way to anticipate the choices, make the tough decisions, and lead the reinvented jobs of the future.