Chapter 1 Introduction

How can society convert to 100 percent renewable energy? The answer to that question is the main topic of this book. Two important aspects must be considered. First, from a technical point of view, which technologies can we use to make sure that the resources available meet the demands? To answer this question, this book presents an energy system analysis methodology and a tool for the design of renewable energy systems. This part includes the results of more than ten comprehensive energy system analysis studies. The large-scale integration of renewable energy into the present system has been analyzed, as well as the implementation of 100 percent renewable energy systems.

Second, in terms of politics and social science, how can society implement such a technological change? To answer that question, this book introduces a theoretical framework approach, which aims at understanding how major technological changes, such as renewable energy, can be implemented at both the national and international levels. This second aspect involves the formulation of the Choice Awareness theory, as well as the analysis of 11 major empirical cases from Denmark and other countries.

With regard to the implementation of the change from fossil fuels to renewable energy, Denmark is an interesting case. Like many other Western countries, Denmark was totally dependent on the import of oil at the time of the first oil crisis in 1973. Almost all transport and residential heating was based on oil. Furthermore, 85 percent of the electricity supplied in Denmark was produced from oil. Altogether, prior to the oil crisis, more than 90 percent of the primary energy supply was based on oil.

Denmark, like many other countries, was unprepared for the sudden rise in oil prices. Danish energy planning had been based on the principle of supplying whatever was demanded. Power stations were planned and built on a prognosis based on the historical development of needs. Denmark had no minister of energy and no energy department, no action plans in the case of being cut off from oil supplies, and no long-term strategy for the future in case oil resources were depleted.

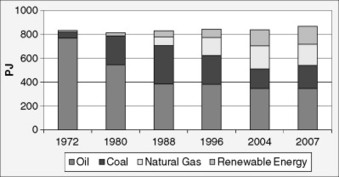

Nevertheless, more than 30 years later, Danish society has proved its ability to implement rather remarkable changes. Figure 1.1 shows the development of the primary energy supply of Denmark since 1972 and illustrates two important factors: Half of the oil consumption has been replaced by other fuels—for example, coal, natural gas, and, to some extent, renewable energy—and Denmark has managed to stabilize the primary energy supply at the same level as in 1972. This stabilization is unique compared to other countries, as it has been achieved simultaneously with a “normal western European” economic growth.

The primary means have been energy conservation and efficiency improvements in supply. Buildings have been insulated, and CHP (combined heat and power) production has been expanded. Thus, 30 years later, the primary energy supply for heating has been reduced to two-thirds of what was used prior to 1973, even though the heated space area has increased by more than 50 percent in the same period. The renewable energy share of the primary energy supply has increased from around zero in 1972 to 16 percent in 2007, and wind power production has become equal to a 20 percent share of the electricity demand. Moreover, Denmark has started to produce oil and natural gas from the North Sea and has, since 1997, been more than self-supplied with energy. However, the Danish oil and gas resources are scarce and are likely to last for only a few decades. An interesting question is, therefore, can Denmark convert to 100 percent renewable energy within a few decades, or will it have to return once again to the former dependence on imported fossil fuels? Such question is indeed relevant not only to Denmark but to Europe in general as well as the United States, China, and many other nations around the world.

The idea of this book is to unify the results and deduce the learning of a number of separate studies and thereby contribute to a coherent understanding of how society can implement renewable energy systems. The book is based on 25 years of involvement in a number of important and representative political decision-making processes in Denmark and other countries. As we shall see, these processes reveal the lack of ability of organizations and institutions linked to existing technologies to produce and promote proposals and alternatives based on radical changes in technology.

On the other hand, the stabilization of the primary energy supply shown in Figure 1.1 proves that the ability to act as a society has been possible, despite conflicts with representatives of the old technologies. In Denmark, during this period, official energy objectives and plans have been developed due to a constant interaction between Parliament and public participation. In this interaction, the description of new technologies and alternative energy plans has played an important role.

The theory of Choice Awareness seeks to understand and explain why the best alternatives are not described and developed per se and what can be done about it. Choice Awareness theory argues that public participation, and thus the awareness of choices, has been an important factor in successful decision-making processes and puts forward four strategies to help along such processes.

1 Book Contents and Structure

Figure 1.2 shows the structure of this book. The Choice Awareness section (the gray area) includes a theoretical understanding and a framework for the development of renewable energy system analysis tools and methodologies (the white area). This chapter introduces both aspects and provides some important definitions.

Chapter 2 introduces the Choice Awareness theory, which deals with how to implement radical technological changes such as renewable energy systems. This theory argues that the perception of reality and the interests of existing organizations will influence the societal perception of choices. Often these organizations seek to hinder radical institutional changes by which they expect to lose power and influence. Choice Awareness theory states that one key factor in this manifestation is the societal perception of having either a choice or no choice.

The Choice Awareness theory presents two theses: The first states that when society defines and wishes to implement objectives implying radical technological change, existing organizations will often seek to create the perception that the radical change in technologies is not an option and that society has no choice but to implement a solution involving the technologies that will save and constitute existing positions. The second thesis argues that, in such situation, society will benefit from focusing on Choice Awareness—that is, raising the awareness that alternatives do exist and that it is possible to make a choice. Four key strategies are identified which society will benefit from following when seeking to raise Choice Awareness.

Chapter 3 elaborates on the Choice Awareness strategies related to the second thesis: the design of concrete technical alternatives, feasibility studies based on institutional economic thinking, the design of public regulation measures, and the promotion of a democratic infrastructure based on new corporative regulation.

Chapter 4 describes the method of designing concrete technical alternatives based on renewable energy technologies. This method distinguishes among three implementation phases: introduction, large-scale integration, and 100 percent renewable energy systems. The need for simulation tools in the two latter phases is especially emphasized. Both methodology and tool development are discussed in relation to the theoretical framework of Choice Awareness, and the energy system analysis tool, EnergyPLAN, is described. The EnergyPLAN model is freeware that can be accessed from the home page, www.EnergyPLAN.eu, together with documentation and a training program.

Chapter 5 refers to and deduces the essence of a wide range of studies of the Danish energy system. In these studies, the EnergyPLAN model has been applied to the analysis of large-scale integration of renewable energy. The Danish energy system is characterized by a high share of renewable energy and is therefore a suitable case for the analysis of further large-scale integration. The question in focus is how to design energy systems with a high capability of utilizing intermittent renewable energy sources. The chapter describes important methodology developments and compares the capability of different systems, including how they treat the fact that the fluctuations and intermittence of, for example, wind power differ from one year to another.

Chapter 6 presents recent results achieved by applying the EnergyPLAN tool to the design of 100 percent renewable energy systems. The question in focus is how to compose and evaluate such systems. The chapter treats the principal changes in the methods of analysis and evaluation applied to such systems compared to systems based on fossil fuels with or without large-scale integration of renewable energy.

Chapter 7 returns to the discussion of the theoretical framework. The chapter refers to a number of cases applying Choice Awareness strategies to specific decision-making processes of energy investments in the period since 1983. Typically, researchers have been involved in these processes by designing and introducing concrete technical alternatives and/or applying other Choice Awareness strategies to the situation. The cases refer to a large number of publications and documentation. Chapter 7 seeks to deduce what can be learned from the cases with regard to the Choice Awareness theses and strategies formulated in Chapters 2 and 3.

Chapter 8 returns to the concerted discussions of the two aspects: Choice Awareness and renewable energy systems. The chapter presents reflections and conclusions drawn from this study in terms of the implementation of renewable energy systems at the societal level.

2 Definitions

Both the issue of Choice Awareness and the case of renewable energy systems involve some basic definitions, which are provided in the following.

Choice Awareness

The theory of Choice Awareness addresses the societal level. It concerns collective decision making in a process involving many individuals and organizations representing different interests and discourses, as well as different levels of power to influence the decision-making process. The term choice obviously plays an important role in the definition of Choice Awareness. The Oxford English Dictionary (2008) defines choice as “the act of choosing; preferential determination between things proposed; selection, election.” Choice involves the act of thinking and the process of judging the pros and cons of multiple options and selecting one of the options for action. This book distinguishes between a true choice and a false choice.

A true choice is a choice between two or more real options, while a false choice refers to a situation in which the choice is some sort of illusion. Some examples of false choices are a Catch-22 and a Hobson’s Choice—in other words, a free choice in which actually only one option is offered. These two types of false choices will be explained further in Chapter 2. More examples of false choices are blackmail and extortion, both involving the condition to either do what you are told or suffer unpleasant consequences.

The Oxford English Dictionary (2008) defines awareness as “the quality or state of being aware; consciousness.” In biological psychology, awareness comprises a person’s perception and cognitive reaction to a condition or event. In principle, awareness does not necessarily imply understanding, just an ability to be conscious of, feel, or perceive. However, here the term is combined with choice, which implies the acts of thinking and judging. Thus, Choice Awareness does involve an element of understanding. Choice Awareness is therefore used here to describe the collective perception of having a true choice. Moreover, this situation involves a cognitive reaction in terms of judging the merits of relevant options and selecting one of them for action.

Collective perception is defined as a general perception in society. It does not include a few individuals who know better or different; the fact that a single person comes up with new ideas or invents new alternatives does not change the collective perception, as long as the person keeps these ideas to him- or herself. Only if individuals raise awareness by convincing or informing the public in general, such knowledge becomes part of the collective perception. In the same manner, the collective perception may be manipulated by individuals or organizations if they prove successful in convincing society in general that a certain alternative does not exist—that is, that it does not comply with technical requirements or other regulations.

Choice-eliminating mechanisms influence the collective perception in the direction of not having a choice at all or having a false choice, as just described. Raising Choice Awareness involves influencing the collective perception in the direction of having a true choice and identifying and understanding the pros and cons of relevant alternatives.

Radical Technological Change

Choice Awareness theory is concerned with the implementation of radical technological change. Technology is defined as one of the means by which mankind reproduces and expands its living conditions. The definition of technology embraces a combination of the four elements—technique, knowledge, organization, and products—and is discussed further in Chapter 2.

Radical technological change is defined as a change of more than one of the four elements of technology. In Choice Awareness, special focus is placed on the change of existing organizations, and a distinction is made between organizations and institutions. Organization is defined as a social arrangement that pursues collective goals, controls its own performance, and has a boundary that separates it from its environment. Typical examples of organizations are companies, NGOs, businesses, and administrative units. Institutions are structures and mechanisms of social order and cooperation. They govern the behavior of more than one individual and/or organization, and they include a formal regime for political rule making and enforcement. Thus, in short, one may say that institutions are organizations including all of the written laws and regulations and all of the unwritten codes of culture regulating them.

Applied and Concrete Economics

Choice Awareness theory involves four strategies in which concrete institutional economics, as opposed to applied neoclassical economics, plays an important role. Applied neoclassical economics is defined as neoclassical-based methods, such as cost-benefit analyses and equilibrium models, applied to existing real-life market economies. This is seen as opposed to theoretically correct methods applied to market economies that fulfill the theoretical assumptions of a free market. As discussed further in Chapter 3, the theory of neoclassical market economics is based on a number of assumptions that are not fulfilled in real-life market economies. The critique of neoclassical-based methods of this book is directed toward the real-life applications of the methods, and it is not decisive whether this critique is valid for theoretically correct applications or not.

Concrete institutional economics is defined as economics that deals with the concrete institutional conditions which form the development of a specific society. Institutional economics focuses on the understanding of the role of human-made institutions in the shaping of economic behavior. The concrete institutional conditions vary from one society to another, and the method linked to concrete institutional economics therefore deals with defining analytical aims, contexts, and aggregation levels for the analysis of the concrete societal institutions in a specific society (Hvelplund 2005, pp. 91–95).

Renewable Energy

Renewable energy is defined as energy that is produced by natural resources—such as sunlight, wind, rain, waves, tides, and geothermal heat—that are naturally replenished within a time span of a few years. Renewable energy includes the technologies that convert natural resources into useful energy services:

- • Wind, wave, tidal, and hydropower (including micro- and river-off hydropower)

- • Solar power (including photovoltaic), solar thermal, and geothermal

- • Biomass and biofuel technologies (including biogas)

- • Renewable fraction of waste (household and industrial waste)

Household and industrial waste is composed of different types of waste. Some parts are considered renewable energy sources—for example, potato peel—whereas other parts, such as plastic products, are not. Only the fraction of waste that is naturally replenished is usually included in the definition. In this book, however, for practical reasons, the whole waste fraction is included as part of the renewable energy sources identified in most analyses.

Renewable Energy Systems

Renewable energy systems are defined as complete energy supply and demand systems based on renewable energy as opposed to nuclear and fossil fuels. They include supply as well as demand. The transition from traditional nuclear and fossil fuel–based systems to renewable energy systems involves coordinated changes in the following:

- • Demand technologies related to energy savings and conservation

- • Efficiency improvements in the supply system, such as CHP

- • Integration of fluctuating renewable energy sources, such as wind power

A distinction can be made between end use and demand. Energy end use is defined as the human call for energy services such as room temperature, transportation, and light. Energy demand is defined as consumer demands for heat, electricity, and fuel. Consumers include households and industry as well as public and private service sectors. Fuel may be used for heating or transport. Heat demand may be divided into different temperature levels such as district heating and process heating.

Within end use, one may distinguish further between, on the one hand, basic needs such as food, basic temperatures, and transportation from home to work and, on the other, specific requirements such as a certain number of square meters with a certain room temperature and a certain number of kilometers of driving. This distinction can be critical—for example, when analyzing the transportation infrastructure related to food production or to transportation between home and work. However, in the analyses presented in this book, it has not been necessary to make such a distinction.

Changes such as insulation and efficiency improvements of electric devices leading to changes in the energy demand for heat, electricity, or fuel are defined as changes in the demand system. In addition to the preceding renewable energy technologies, renewable energy systems include both technologies, which can convert from one form of energy into another—for example, electricity into hydrogen—as well as storage technologies that can save energy from one hour to another. Mathiesen (Mathiesen and Lund 2009) and Blarke (Blarke and Lund 2008) comprise these technologies under the designation relocation technologies. However, in the following, the difference between energy conversion and energy storage technologies is emphasized.

Energy conversion technologies are technologies that can convert from one demand (heat, electricity, or fuel) to another, such as the following:

- • Conversion of fuel into heat and/or electricity by the use of technologies such as power stations, boilers, and CHP (including steam turbines as well as fuel cells)

- • Conversion of electricity into heat by the use of technologies such as electric boilers and heat pumps

- • Conversion of solid fuels into gas or liquid fuel by the use of technologies such as electrolyzers and biogas and biofuel plants

Energy storage technologies are defined as technologies that can store various forms of energy from one hour to another, such as the following:

- • Fuel, heat, and electricity storage technologies

- • Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES)

- • Hydrogen storage technologies

Keep in mind that the definition of storage technologies is broader than the concept of storage itself. For example, in the case of electricity, which is stored by converting it into hydrogen, the storage technology may include conversion technologies such as electrolyzers and fuel cells. The distinction between conversion and storage technologies is defined by the purpose of the technology in question. If the purpose is to convert electricity to hydrogen because a car needs hydrogen, then the electrolyzer is defined as a conversion technology. However, if the purpose is to store electricity, then the combination of electrolyzer, hydrogen storage, and fuel cell is defined as a storage technology.

In complex renewable energy systems, single components may be used for both purposes. For instance, the same electrolyzer may be used to supply cars with hydrogen and at the same time produce hydrogen for storage purposes. In this case, the electrolyzer is simply regarded as both a conversion and a storage technology.

The distinction between the two types of technologies is important when designing renewable energy systems, as will be elaborated on in Chapters 4 to 6. It is important to distinguish between, on the one hand, the need for balancing time and, on the other, the need for balancing the annual amounts of different types of energy demands.

3 Renewable versus Sustainable

This book often uses the term renewable energy, but why not use sustainable energy instead? After all, in many situations, these two terms are used interchangeably. In typical definitions, however, significant differences can be found between the two terms. So renewable is used for good reason, even though the difference between the two terms to some extent relies on the definitions of each of them.

Sustainable Energy

Sustainable energy can be defined as energy sources that are not expected to be depleted in a time frame relevant to the human race and that therefore contribute to the sustainability of all species.

This definition of sustainable energy and the preceding definition of renewable energy represent typical definitions of both terms. They match rather closely the definitions given by the Internet encyclopedia Wikipedia. These definitions, however, reveal a difference in the significance of the two terms. Most important, Wikipedia (2008) includes the word nuclear in the sources defined as sustainable energy sources. However, as Wikipedia adds, for social and political reasons, there is a controversy with regard to whether nuclear sources should be regarded as sustainable. Nevertheless, at the present technological stage, nuclear is not sustainable, since it needs uranium, which is a scarce resource within the relevant time frame.

The same discussions seem to apply to carbon capture technologies, which have recently been promoted as an important solution in the debate on how to combat climate change. Very often this solution is proposed in relation to the use of fossil fuels, especially coal. Often the question is posed, why not continue to burn coal and even invest in new coal-fired power stations when such technology can be made sustainable by use of carbon capture?

On the other hand, even though sustainable energy sources are most often considered to include all renewable sources, some renewable energy sources do not necessarily fulfill the requirements of sustainability. For instance, the production of biofuels such as ethanol from fermentation has in some life cycle analyses proven to be nonsustainable. Again, this is a controversy that has not yet found a consensus.

Nevertheless, the conclusion is that sustainable energy in some definitions may include nuclear and fossil fuels in combination with carbon capture, while such technologies and sources are not included in the definition of renewable energy. On the other hand, renewable energy may include some biomass resources that may prove not to be sustainable.

Political Reasons for Renewable Energy

Besides the preceding difference, another important disparity exists between renewable and sustainable. This has to do with the reasons for wishing technological change. Why does society want to implement renewable energy solutions? And why does society aim at implementing sustainable energy solutions? The reasons for introducing sustainable solutions are mainly—if not solely—related to an environmental motive. However, several reasons can be found for implementing renewable energy.

In the article “Choice Awareness” (Lund 2000) and in Chapter 23 of the book Tools for Sustainable Development (Lund 2007b), I described the recent history of Danish energy planning and policy since the first oil crisis in 1973. At least three main reasons can be defined for replacing fossil fuels by technologies related to renewable energy systems, including energy conservation and efficiency measures:

- • Energy security, with an emphasis on oil dependence (and oil depletion). This reason played the all-important role in Danish society in the 1970s and has, in the beginning of the twenty-first century, experienced a revival caused by increasing oil prices in combination with the relations between the Western world and the governments in power of the remaining oil reserves.

- • Economics, with an emphasis on job creation, industrial innovation, and the balance of payment. This reason took over and played a major role in Denmark in the 1980s. The main problem changed from being based on the issue of whether we could get the oil to whether we could afford it. This reason became the driving political force behind the industrial development of, among others, solar thermal and wind power in Denmark in the 1980s and 1990s.

- • Environment and development, with an emphasis on climate change. This third reason became a key issue in the 1990s after the introduction of the Brundtland report (United Nations 1987) and has since been of increasing social importance along with the rising discussions on global warming.

All three of these reasons have formed part of the political discussions and have been identified as political goals in Danish Energy Policy during the whole period. However, the main focus has changed in such way that each reason has been considered the most important one from one decade to another.

The concerns related to energy security are based on the underlying fact that fossil fuels constitute a limited resource. The United Nations’ discussions on environment and development are based on the fact that energy consumptions are indeed not equally distributed between what is considered the rich and the poor countries of the world, respectively. This is described and discussed in relation to the rising global energy consumption in the paper “The Kyoto Mechanisms and Technological Change” (Lund 2006a). In the paper, it is argued that the introduction of the so-called Kyoto mechanisms actually had the opposite effect of what the UN intended. The Kyoto mechanisms allow rich countries to implement climate change projects in other countries instead of decreasing their own emissions. Thereby, they increase the differences in energy consumption between rich and poor countries rather than decreasing them. Moreover, the mechanisms may slow down the needed technological development.

With regard to the discussion of the difference between renewable and sustainable energy, a main point is that if society accepts nuclear power and fossil fuels in combination with carbon capture as parts of the solution, society may be able to achieve parts of the environmental goals. However, society will not be able to solve the fundamental problems of scarce and limited resources of fossil fuels and uranium. Seen from the point of view of a Western country such as Denmark, society will not be able to meet the goals of energy security, and, with regard to economics, Denmark will still have to import fossil fuels and/or uranium.

Renewable Energy and Democracy

Another difference between renewable and sustainable energy is worth discussing. This difference has democracy as its main focus and is quite relevant to the issue of energy systems and the implementation of technological change such as those addressed by the Choice Awareness theory, as we shall see in Chapter 2.

In the 1970s, an energy movement arose in Denmark as in many other Western countries. This movement was constituted among others by the antinuclear movement (OOA) and the Danish Organization for Renewable Energy (OVE). When the OOA was created and these energy problems were discussed, the issues of democracy and living conditions in local communities played major roles in the arguments against nuclear and in favor of renewable energy. With regard to nuclear, some were afraid of the consequences of such technology in terms of security and ownership. The question was how to guard the plants and the transport of radioactive waste without having to hire security staff and erecting fences. Who should own and operate these big power stations? If ownership was assigned to big companies, it would mean that local communities would lose influence. Also, how should space for nuclear power stations be allocated and radioactive waste be disposed of without impacting the quality of life for the communities involved? The antinuclear movement (OOA 1980) discussed all of these concerns, as well as the relations between nuclear power and nuclear weapons.

The issue of local ownership also played an important role in discussions on renewable energy. Since most people feel it is better to have an influence on such decisions, the citizens in these local communities preferred to have their own renewable sources of energy instead of depending on nuclear or imported fossil fuels (OVE 2000). As we shall see in the next chapter, these beliefs conform to the concept of Choice Awareness, which highlights the benefits of choice in creating a “life worth living” at both the individual and societal levels.

In such a view, the difference between renewable and sustainable energy becomes important. If society accepts nuclear power and fossil fuels in combination with carbon capture as major parts of the solution, the technological change may not meet the local communities’ wishes to improve their influence on decisions that are important to their lives. In short, one can say that the implementation of renewable energy systems helps to create what in Chapter 3, according to the Choice Awareness theory, is called a suitable democratic infrastructure. This suitable democratic infrastructure may improve the awareness of choices and thereby, in general, create better living conditions. On the other hand, an improved democratic infrastructure will also improve the circumstances for making the choice of implementing renewable energy systems. More important, depending on the specific definition applied, this may not be the case with sustainable energy systems. Based on these considerations, the term renewable energy systems is used in this book.