Appendix A. Overview of the Restlet Framework

This appendix continues the tour of the Restlet Framework started in the first chapter. It begins with a description of Restlet’s core module (which provides the Restlet API and its implementation, also known as the Restlet Engine) and extensions built on top of the core module. We then present the notion of editions, which is the way for the Restlet Framework to adapt to various technical contexts while still providing the same high-level API. We conclude this appendix by explaining the versioning scheme used, including the release tags such as stable, testing, and unstable.

A.1. Restlet API

The most important part of the Restlet Framework is its Restlet API. Once you learn it, you can understand most Restlet code and develop both client-side and server-side applications—or make use of many protocols beside HTTP. In contrast with the JAX-RS API, the Servlet API, or the HttpURLConnection class, Restlet uses a single uniform API, making it easy to write not only servers, but clients and even web proxies (applications acting both as server and client) in order to build cache systems or web API mashups.

Another benefit of building your applications on top of this Java API is that it doesn’t require any dependency on third-party libraries, besides the standard libraries provided by your target environment. Also, the whole API has been designed to be thread-safe, ensuring consistent and efficient behavior when multiple threads access an object, either at the same time (concurrency) or at a different time (changes visibility).

Therefore, if you’re careful regarding other dependencies, you can build your web applications on top of the Restlet API and ensure that they run equally well in several environments, such as Java SE, Java EE, OSGi, and Google App Engine for a server-side application, or Java SE, OSGi, Android, and GWT for a client-side application.

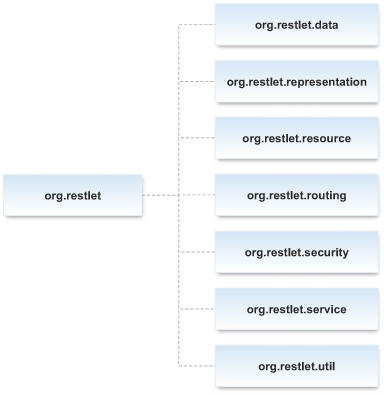

By now, you’re probably eager to understand what the Restlet API looks like in detail. Under the root org.restlet Java package, you can find seven subpackages as illustrated in figure A.1.

Figure A.1. The Restlet API packages

Let’s review the purpose and content of each package.

A.1.1. Root package

The top-level package org.restlet contains the most important artifacts. First there’s the Uniform interface containing a single handle(Request, Response) method that embodies the principle of uniform interface for REST resources and the stateless nature of REST communications. Then there’s a hierarchy of core classes inheriting from Restlet. Figure A.2 illustrates their organization.

Figure A.2. Hierarchy of classes in the root package

The Restlet class implements the Uniform interface and provides the equivalent of the widely known javax.servlet.http.HttpServlet class. There are important differences, such as the way requests and responses abstract low-level details of HTTP in Restlet where the Servlet API leaves a lot of work in the hands of the developer. A good example is that in Restlet you don’t have to manually parse HTTP headers—all that work is done for you, and the useful information is available as Java classes and properties. You can get more detail in the book’s chapters, including section 4.1.1 and section 7.4.2, as well as an exhaustive mapping list in section 3 of appendix E, titled “Mapping HTTP headers to Restlet properties.”

Contrary to the Servlet API, you’ll rarely need to directly subclass Restlet because the framework offers higher-level abstractions such as the ServerResource class. The advantage of the Restlet class is that its instances can be accessed concurrently by multiple threads in order to serve several requests at the same time, but this requires a good understanding of Java concurrency programming, equivalent to what is required for Servlet programming.

The Application class is commonly extended to develop complete web applications and is extensively covered in chapter 2. You also have the Component, Connector, Client, and Server classes corresponding exactly to the REST architecture elements that we introduce in chapter 1. Those classes are necessary when you deploy your applications, as explained in chapter 3.

The Context class provides contextual features to a set of Restlet instances that are part of the same container, typically a Component or an Application. You’ll be able to store attributes and parameters in this context, or access features provided by the container such as a logger, default credentials, verifiers, or a way to invoke connectors.

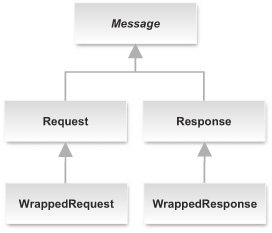

The root package contains classes that embody the messages exchanged between components, either requests or responses, as illustrated in figure 1.7 where we discuss REST connectors.

Naturally, the Restlet API strictly respects REST and has a hierarchy between its Message, Request, and Response classes, as depicted in figure A.3.

Figure A.3. Message hierarchy

A.1.2. Data package

The org.restlet.data package contains classes used to read or write those messages which are composed of several properties, such as the request method (Method, Conditions), response status (Status), URI references (Reference), authentication information (ChallengeScheme, ChallengeRequest, and ChallengeResponse), agent information (ClientInfo, Preference and ServerInfo), or representation metadata (Character-Set, Encoding, Language, MediaType).

There are also classes to facilitate the management of URI query parameters and web forms (Form and Parameter classes).

A.1.3. Representation package

Not all data elements were included in the data package! We didn’t cover the representations of resources that are sent or received in the body of the messages. As previously illustrated in figure 1.4, remember that in REST, clients manipulate resources through representations of their state.

Naturally, Restlet supports representations via a Representation class and a broad set of subclasses covering the most common types. Figure A.4 shows the top of this hierarchy of classes. The ancestor class Variant describes a representation with enough metadata to support content negotiation—one of the powerful and often forgotten features of HTTP.

Figure A.4. Representation hierarchy

The RepresentationInfo class adds a few more properties necessary to support conditional methods, another powerful feature of HTTP. Finally we reach the abstract Representation class, mother of all concrete representations in Restlet.

To produce representations, you need to provide concrete content. This content can be based on character strings (StringRepresentation and Appendable-Representation), byte streams (StreamRepresentation, Input Representation, ByteArrayRepresentation, and OutputRepresentation), character streams (Character Representation, ReaderRepresentation, WriterRepresentation), or byte channels (ChannelRepresentation, ReadableRepresentation, WritableRepresentation).

There are also special cases for representations based on files (FileRepresentation), serializable Java objects (ObjectRepresentation), and empty ones (Empty Representation). It’s also possible to compute the digest (like a checksum) for any representation using a wrapper (DigesterRepresentation).

Other types of representation are available via extension packages, as you’ll see later in this section. We cover this topic more extensively in chapter 4.

A.1.4. Resource package

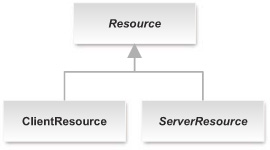

The org.restlet.resource package contains the higher-level classes that you’ll use to create client-side resource proxies (ClientResource) or extend to create server-side resource implementations (ServerResource). We used those two classes to write our “Hello World” example in chapter 1, and we cover their use in detail in section 2.5. Figure A.5 shows the hierarchy composed with the parent Resource class (renamed from UniformResource since version 2.1).

Figure A.5. Resource hierarchy

This package also defines the common annotations used in ServerResource subclasses to facilitate the mapping between RESTful methods (typically HTTP methods) and the handling Java methods: @Get, @Put, @Delete, and @Post. You’ll find the convenient Directory class can expose a hierarchy of static files as RESTful resources (covered in section 7.1.3).

A.1.5. Routing package

The org.restlet.routing package contains all classes directly related to routing. When a request is received, there’s a need to route it along a predefined path in order to reach the target ServerResource subclass or a Restlet instance that will effectively handle it and return a response. This need comes from the fact that your application will likely contain several resources with different URIs or will need to apply specific filters for different resources—for example, for security or validation reasons. Figure A.6 shows how routing is supported via a set of Restlet subclasses.

Figure A.6. Routing hierarchy

The Filter class preprocesses the request, invokes an attached Restlet, and post-processes the response. Several specialized filters are provided, like an Extractor (looking up data like cookies and query parameters and storing them as request attributes) and a Validator (validating an attribute’s value against regular expressions). The Redirector class supports either client-side redirections (via special response statuses) or server-side redirections (often called reverse proxying).

The Router class attempts to match the URI in the request against URI patterns defined by your application to determine which ServerResource class or Restlet instance to target. There’s also VirtualHost, a specialized router that adds the ability to match virtual hosts by domain name, IP address, and other properties.

A.1.6. Security package

Security is an important topic related to routing that deserves its own package: org.restlet.security. Two classic aspects are covered: authentication and authorization via a set of filters, as illustrated in figure A.7.

Figure A.7. Security hierarchy

The authentication step is managed by the Authenticator class and the more specialized ChallengeAuthenticator subclass, helped by the Enroler interface, adding Role instances to the authenticated User, and the Verifier interface (with SecretVerifier, LocalVerifier, and MapVerifier implementations) to verify the user credentials during challenge authentication.

Then authorization is managed by the Authorizer class and more specialized subclasses (ConfidentialAuthorizer, Method-Authorizer, and RoleAuthorizer). It can also be checked with a finer precision inside your server resources code via isInRole() method calls.

The Restlet security API also offers a clean separation between the unique way each application happens to define roles and the management of users, which is specific to each organization and deployment environment. Therefore, a notion of Realm is provided, exposing a contextual Verifier and Enroler. A default MemoryRealm is provided, supporting complex mappings between a Group and its User instances on one side and Role instances defined by a given application on the other side.

We discuss this dense and important topic at length in chapter 5.

A.1.7. Service package

One of the advantages of Restlet is that your application or component automatically benefits from powerful features via a set of services included in the org.restlet .service package. It includes a parent Service class and several subclasses (Connector-Service, ConnegService, ConverterService, DecoderService, EncoderService, LogService, MetadataService, RangeService, StatusService, TaskService, and TunnelService). Each service has a lifecycle with start and stop methods and can add inbound or outbound filters to the container for which they’re enabled.

For example, RangeService supports the retrieval of partial representations of resources, without having to change anything in your Restlet code. You can disable this service, like all others, if necessary.

You may guess the purpose of some other services mentioned by their class name, but we describe them individually in the book when we discuss the topic to which they belong. In addition, we explain the common aspects to all services in section 2.3.4.

A.1.8. Util package

As its name implies, org.restlet.util contains several utility classes, such as wrapper classes and a string template mechanism (Template, Variable, and Resolver), covered in section 2.4.2 during a discussion of URI templates.

It also contains a generic Series class implementing the java.util.List interface to manage series of parameters that come in as name=value pairs. For example, the Form class that we mentioned in the Data package derives from this Series class.

A.2. Restlet Engine

Now that you have a good overview of the Restlet API and the features it offers, we suggest you briefly look under the hood and see how the Restlet Engine is designed. We won’t cover the engine in detail, as it’s rarely necessary for Restlet users to have such a deep level of knowledge of its internals.

Keep in mind that besides classes implementing the Restlet API, built-in HTTP client and server connectors can be used during development. For production environments, we currently recommend using the more robust HTTP connectors (based on Jetty or Simple) that are also provided in the Restlet distribution or to deploy to full-blown Servlet or OSGi containers. We cover the deployment of your applications more extensively in chapter 3.

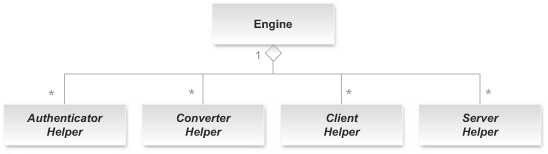

The root package org.restlet.engine contains a singleton of the Engine class for the whole JVM. This Engine singleton supports all applications, components, and connectors hosted in the current JVM and is a registry managing several sorts of plug-ins that inherit the Helper class as illustrated in figure A.8.

Figure A.8. The Restlet Engine can be extended with pluggable helpers.

AuthenticatorHelper instances support authentication schemes such as HTTP Basic, HTTP Digest, SMTP Plain, Amazon Web Services (S3 and all other services), or Microsoft SharedKey. ConverterHelper instances perform conversions between Java objects and Restlet representations to support the ConverterService mentioned in the description of the Service package. ClientHelper instances provide client connectors for URI schemes such as HTTP, FILE, or ZIP. ServerHelper instances do the same for server connectors.

The fact that new helpers can be registered, either dynamically by adding a specific JAR in the classpath or by programmatically configuring the Engine instance, is quite powerful. As we said, you’ll rarely need to know more about this topic, so let’s move right away to the extensions you can use in your Restlet applications.

A.3. Extensions

Even though the Restlet API has a broad features scope, it attempts to stay as neutral as possible. It doesn’t, for example, enforce any particular presentation or persistence technology. Instead, a wide set of Restlet Extensions is offered in order to match the most common use cases. Three categories of extensions are provided:

- Those that add support for standards like Atom/AtomPub, cryptography, HTML forms, JAAS authentication, JAX-RS, JSON, OAuth, OData, OpenID, RDF, SIP, SSL, WADL, and XML.

- Those that provide new connectors such as Apache HTTP Client, JavaMail (SMTP and POP3 clients), JDBC, Jetty (HTTP server), Net (FTP and HTTP client based on java.net.HttpURLConnection), Simple Framework (HTTP server), and Servlet integration (HTTP pseudo-server).

- Those that provide integration with third-party services such as template engines like FreeMarker or Apache Velocity, multipart handling via Apache FileUpload, XML serialization via EMF, GWT, Jackson, JAXB, JiBX, and XStream. Extensions also provide integration with technologies such as Lucene, ROME, SLF4J, Spring, and Oracle XDB.

That provides a lot of options for your applications! Keep in mind that each extension is available in a dedicated org.restlet.ext.<code> package, where <code> is the standard or technology name such as atom or xml. In the next section, we explain how the Restlet Framework is distributed via several editions.

A.4. Editions

The core org.restlet module ships the Restlet API and the Restlet Engine. Initially available in standalone mode on top of Java SE, an optional integration with Java EE and Servlet containers has quickly been developed. This integration was easy, as it left the primary Restlet API almost intact and provides a new Servlet extension that bridges the Servlet API and the Restlet API. Then other platforms developed by Google appeared: Google Web Toolkit, Android, Google App Engine. They’re similar only in the fact that they support a subset of the Java SE APIs. GWT is also particular in the sense that it proposes only a client API.

Because the Restlet API had to be manually adjusted to work in these different contexts, the idea of several editions of the core module emerged. An edition is dedicated to a given platform and provides the core module which defines the Restlet API available, its implementation, and a subset of extensions.

The six editions available in version 2.1 are Java SE, Java EE, GAE, GWT, Android, and OSGi. We include a table listing the extensions available by editions.

A.4.1. Edition for Java SE

This edition is aimed for development and deployment of Restlet applications inside a regular JVM. Because it relies on a standard JVM, few restrictions apply: it provides most of the extensions except the ones linked with the Java EE specification, such as the Servlet, Oracle XDB, and the ones specifically linked with the Google App Engine platform. It’s compatible with release 1.5 of the Java SE and higher.

A.4.2. Edition for Java EE

This edition targets the development and deployment of Restlet applications on Java EE application servers, or more precisely on Servlet containers such as Tomcat and WebLogic. It contains all extensions except the ones for HTTP server connectors such as Simple and Jetty, because the Servlet container already provides that. Also, this edition doesn’t contain the GAE extension specific to the GAE edition. It’s compatible with Servlet API version 2.5 and above, as well as the Java EE 5.0 specification and above.

A.4.3. Edition for OSGi environments

This edition includes the core module and the whole set of extensions adapted to the Open Services Gateway initiative platform (OSGi) except the GAE extension. Contrary to the Java SE and Java EE edition previously discussed, this edition can work either using standalone HTTP servers or the pseudoserver provided by the Servlet extension bridge.

All these modules are plain OSGi bundles including an Activator class when necessary and a proper manifest file.

A.4.4. Edition for Google App Engine

This edition gathers the core module and a set of extensions adapted to the Google App Engine (GAE) solution. Due to the restrictions of the GAE platform based on Java 6, with a restricted list of APIs entirely or partly supported, we need to provide an adaptation of Restlet for this environment. Because GAE relies on the Servlet API for server-side aspects, it can be seen as an adaptation of the Java EE edition. The client API is supported via the Net extension, but not the NIO-based implementation of the internal connector, because sockets and threads can’t be directly created. This edition is compatible with Google App Engine 1.4.3 and above.

A.4.5. Edition for Google Web Toolkit

GWT is a platform dedicated to the development of applications running in a web browser. By default, a custom GWT-RPC mechanism is provided to communicate with a custom Servlet-based server. The port of the Restlet Framework enables you to loosen this tight coupling and helps you expose your server resources on other back-end technologies. The communication is based on the same client API used in an asynchronous way. Also, due to underlying AJAX constraints, NIO channels and BIO streams can’t be supported.

Restlet Framework 2.0 added support for annotated Restlet interfaces and automatic bean serialization into its GWT edition in a way that’s consistent with other editions. This edition is compatible with GWT 2.2 and above.

A.4.6. Edition for Android

The port of Restlet on Android includes both client and server APIs. You may wonder about the reason to provide another client API addition to the one already shipped with Android, which relies on the Apache HTTP Client library. One reason is that the client-side API of the Restlet Framework provides higher-level features than the default HTTP client library, such as integrated support of conditional requests, content negotiation, and other protocols. It can also rely on the Apache HTTP Client using the related Restlet extension.

You may also wonder why you would have a web server on a mobile phone. Here are some reasons:

- You can test web applications during the development phase without having to consume network access, which might be limited by cost or availability in some areas.

- You can allow third-party applications on other phones or other platforms to remotely access your device. This requires strong security mechanisms provided in part by the Restlet Framework as well as network-level authorizations by the carrier, if any.

- You can run local Android applications that are using the internal web browser and behaving like regular hypermedia applications.

Contrary to other editions, the Android edition can’t use Restlet’s autodiscovery mechanism for connectors and converters provided as Restlet extensions. This is due to a limitation in the way Android repackages JAR files, leaving out the descriptor files in the META-INF/services/ packages used by the Restlet Framework for autodiscovery. The workaround consist of manually registering those additional connectors and converters in the Restlet engine. Here’s an example for the Jackson converter:

Engine.getInstance().getRegisteredConverters().add(new JacksonConverter());

You may also face another blocking error. The internal HTTP client has been rewritten using the java.nio.package. This may lead, on some Android devices, to this kind of exception: java.net.SocketException: Bad address family. In this case, you can turn off the IPv6 preference as follows:

System.setProperty("java.net.preferIPv6Addresses", "false");

A.4.7. Matrix of extensions per edition

Table A.1 exposes the list of the developed extensions (by their short name, which is the abbreviation of their root package name: org.restlet.ext.<extension>) and their availability by edition.

Table A.1. Developed extensions by edition

A.5. Restlet versioning

It’s important that you understand the Restlet versioning to assess which version is best to use for your projects.

A.5.1. Logical versions

Apart from the classical version numbers used, the Restlet Framework offers three versions, following the naming convention of the Debian Linux project:

- Stable is the release recommended for applications in production. The API of this release is frozen, and only bug fixes are made.

- Testing is the release recommended for new developments. The community is involved, and contributions of any kind (feedback, bugs, missing features, code, patches, and bug fixes) are welcomed.

- Unstable is the release where active development happens. It corresponds to builds of the development trunk passing all unit tests.

The unstable release is generated every eight hours, assuming the code has been updated. The testing and stable releases are tagged in the revision control system (currently a GitHub repository) and are refreshed once the set of changes is important enough.

Following the Git naming, the unstable and testing releases are taken from the master branch, whereas the stable release is built from a numbered branch, such as the 2.1 branch. The unstable release equals the testing version plus a set of enhancements and bugs fixes, but sometimes a regression can be introduced.

A.5.2. Versioning scheme

Restlet versions are composed of a standard triplet: major.minor.release. A major version corresponds to deep changes in the Restlet API without a guarantee of incremental compatibility, whereas the minor version denotes lighter changes: deprecated classes or methods are removed, and extensions can also be added or removed.

Release is typically a numeric value. It starts from 0, then is incremented each time a bug-fixing version is released. This value can also be milestone (abbreviated m) or release candidate (abbreviated rc) concatenated with an increment (for example: 2.1m5, 2.1rc2, and so on). Milestones are released in the active phase of development where the framework can change freely. The intent of candidate releases is to freeze the features set and the API and only change it in case of design issues or bugs.

Generally speaking, the lifecycle of releases lasts about two years, even if there’s a goal to lower it. Version 1.0.0 was released in April 2007; 1.1.0 in October 2008; 2.0.0 in July 2010; and 2.1 is planned for September 2012.