Chapter 8. Basic Login

Now that new users can sign up for our site (Chapter 7), it’s time to give them the ability to log in and log out. In this chapter, we’ll implement a basic but still fully functional login system: the application will maintain the logged-in state until the browser is closed by the user. The resulting authentication system will allow us to customize the site and implement an authorization model based on login status and identity of the current user. For example, we’ll be able to update the site header with login/logout links and a profile link.

In Chapter 10, we’ll impose a security model in which only logged-in users can visit the user index page, only the correct user can access the page for editing their information, and only administrative users can delete other users from the database. Finally, in Chapter 13, we’ll use the identity of a logged-in user to create microposts associated with that user, and in Chapter 14 we’ll allow the current user to follow other users of the application (thereby receiving a feed of their microposts).

The authentication system from this chapter will also serve a foundation for the more advanced login system developed in Chapter 9. Instead of “forgetting” users on browser close, Chapter 9 will start by automatically remembering users and will then optionally remember users based on the value of a “remember me” checkbox. As a result, taken together, Chapter 8 and Chapter 9 develop all three of the most common types of login systems on the web.

8.1 Sessions

HTTP is a stateless protocol, treating each request as an independent transaction that is unable to use information from any previous requests. This means there is no way within the hypertext transfer protocol to remember a user’s identity from page to page; instead, web applications requiring user login must use a session, which is a semi-permanent connection between two computers (such as a client computer running a web browser and a server running Rails).

The most common techniques for implementing sessions in Rails involve using cookies, which are small pieces of text placed on the user’s browser. Because cookies persist from one page to the next, they can store information (such as a user id) that can be used by the application to retrieve the logged-in user from the database. In this section and in Section 8.2, we’ll use the Rails method called session to make temporary sessions that expire automatically on browser close.1 In Chapter 9, we’ll learn how to make longer-lived sessions using the closely related cookies method.

1. Some browsers offer an option to restore such sessions via a “continue where you left off” feature, but of course Rails has no control over this behavior.

It’s convenient to model sessions as a RESTful resource: visiting the login page will render a form for new sessions, logging in will create a session, and logging out will destroy it. Unlike the Users resource, which uses a database back-end (via the User model) to persist data, the Sessions resource will use cookies, and much of the work involved in login comes from building this cookie-based authentication machinery. In this section and the next, we’ll prepare for this work by constructing a Sessions controller, a login form, and the relevant controller actions. We’ll then complete user login in Section 8.2 by adding the necessary session-manipulation code.

As in previous chapters, we’ll do our work on a topic branch and merge in the changes at the end:

$ git checkout -b basic-login

8.1.1 Sessions Controller

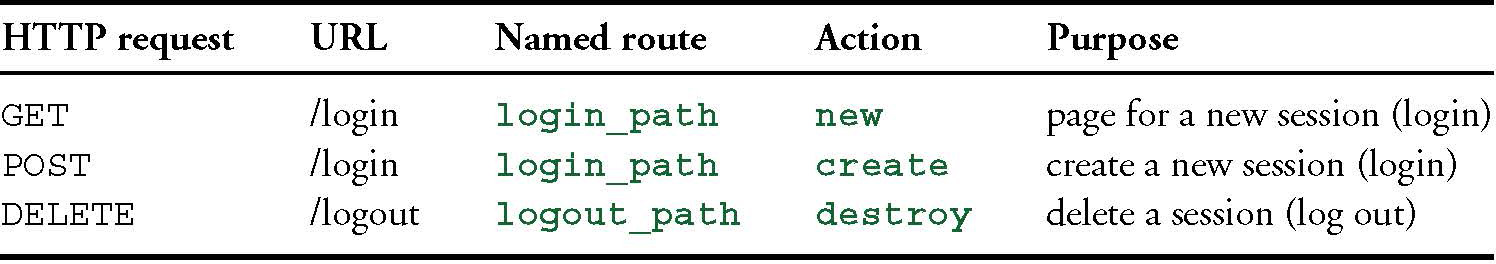

The elements of logging in and out correspond to particular REST actions of the Sessions controller: the login form is handled by the new action (covered in this section), actually logging in is handled by sending a POST request to the create action (Section 8.2), and logging out is handled by sending a DELETE request to the destroy action (Section 8.3). (Recall the association of HTTP verbs with REST actions from Table 7.1.)

To get started, we’ll generate a Sessions controller with a new action (Listing 8.1).

Listing 8.1: Generating the Sessions controller.

$ rails generate controller Sessions new

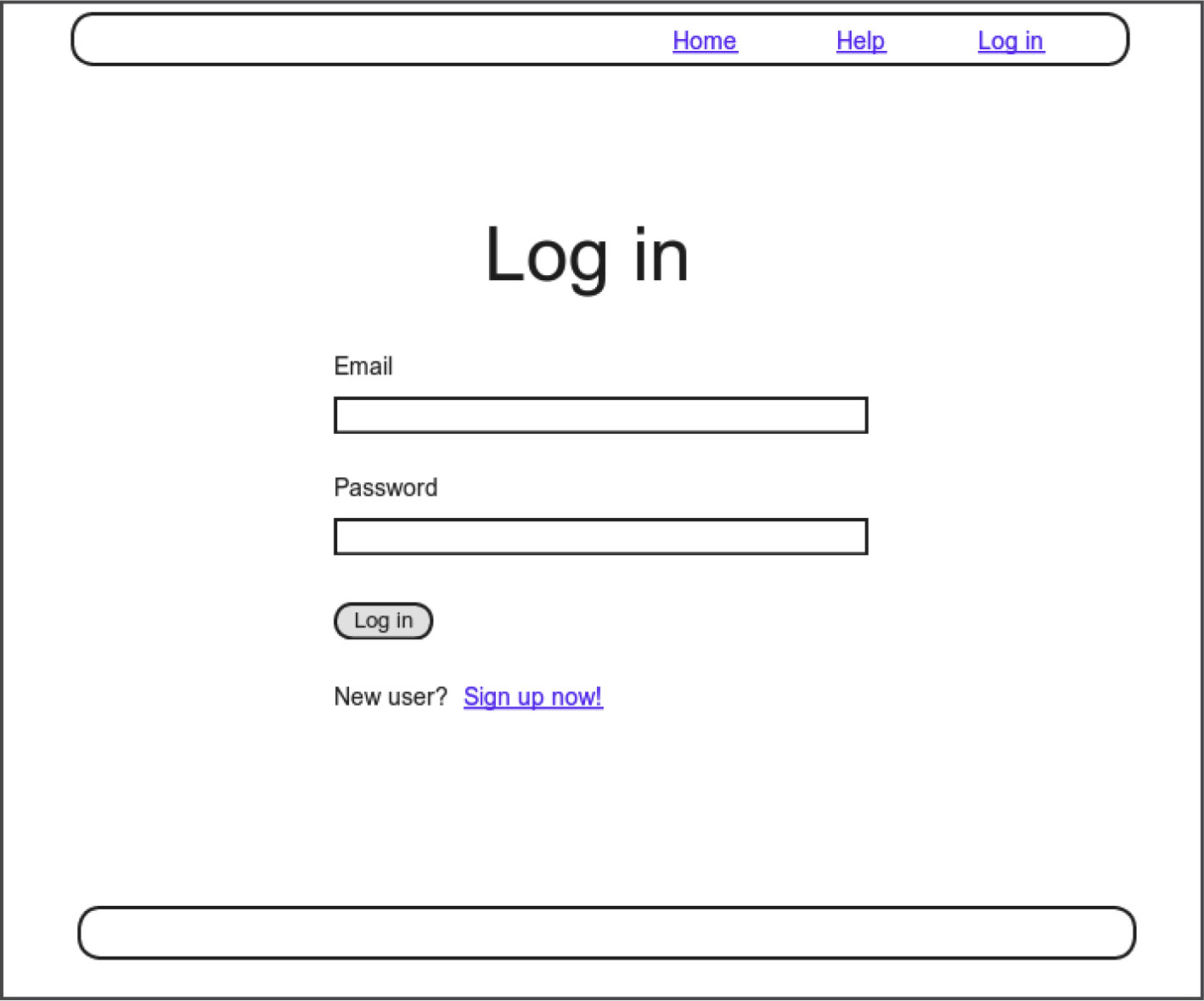

(Including new actually generates views as well, which is why we don’t include actions like create and destroy that don’t correspond to views.) Following the model from Section 7.2 for the signup page, our plan is to create a login form for creating new sessions, as mocked up in Figure 8.1.

Unlike the Users resource, which used the special resources method to obtain a full suite of RESTful routes automatically (Listing 7.3), the Sessions resource will use only named routes, handling GET and POST requests with the login route and DELETE request with the logout route. The result appears in Listing 8.2 (which also deletes the unneeded routes generated by rails generate controller).

Listing 8.2: Adding a resource to get the standard RESTful actions for sessions. RED

config/routes.rb

Rails.application.routes.draw do

root 'static_pages#home'

get '/help', to: 'static_pages#help'

get '/about', to: 'static_pages#about'

get '/contact', to: 'static_pages#contact'

get '/signup', to: 'users#new'

get '/login', to: 'sessions#new'

post '/login', to: 'sessions#create'

delete '/logout', to: 'sessions#destroy'

resources :users

end

With the routes in Listing 8.2, we also need to update the test generated in Listing 8.1 with the new login route, as shown in Listing 8.3.

Listing 8.3: Updating the Sessions controller test to use the signup route. GREEN

test/controllers/sessions_controller_test.rb

require 'test_helper'

class SessionsControllerTest < ActionDispatch::IntegrationTest

test "should get new" do

get login_path

assert_response :success

end

end

The routes defined in Listing 8.2 correspond to URLs and actions similar to those for users (Table 7.1), as shown in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1: Routes provided by the sessions rules in Listing 8.2.

Since we’ve now added several custom named routes, it’s useful to look at the complete list of the routes for our application, which we can generate using rails routes:

$ rails routes

Prefix Verb URI Pattern Controller#Action

root GET / static_pages#home

help GET /help(.:format) static_pages#help

about GET /about(.:format) static_pages#about

contact GET /contact(.:format) static_pages#contact

signup GET /signup(.:format) users#new

login GET /login(.:format) sessions#new

POST /login(.:format) sessions#create

logout DELETE /logout(.:format) sessions#destroy

users GET /users(.:format) users#index

POST /users(.:format) users#create

new_user GET /users/new(.:format) users#new

edit_user GET /users/:id/edit(.:format) users#edit

user GET /users/:id(.:format) users#show

PATCH /users/:id(.:format) users#update

PUT /users/:id(.:format) users#update

DELETE /users/:id(.:format) users#destroy

It’s not necessary to understand the results in detail, but viewing the routes in this manner gives us a high-level overview of the actions supported by our application.

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. What is the difference between GET login_path and POST login_path?

2. By piping the results of rails routes to grep, list all the routes associated with the Users resource. Do the same for Sessions. How many routes does each resource have? Hint: Refer to the section on grep in Learn Enough Command Line to Be Dangerous.

8.1.2 Login Form

Having defined the relevant controller and route, now we’ll fill in the view for new sessions, i.e., the login form. Comparing Figure 8.1 with Figure 7.11, we see that the login form is similar in appearance to the signup form, except with two fields (email and password) in place of four.

As seen in Figure 8.2, when the login information is invalid we want to re-render the login page and display an error message. In Section 7.3.3, we used an error-messages partial to display error messages, but we saw in that section that those messages are provided automatically by Active Record. This won’t work for session creation errors because the session isn’t an Active Record object, so we’ll render the error as a flash message instead.

Recall from Listing 7.15 that the signup form uses the form_for helper, taking as an argument the user instance variable @user:

<%= form_for(@user) do |f| %>

.

.

.

<% end %>

The main difference between the session form and the signup form is that we have no Session model, and hence no analogue for the @user variable. This means that, in constructing the new session form, we have to give form_for slightly more information; in particular, whereas

form_for(@user)

allows Rails to infer that the action of the form should be to POST to the URL /users, in the case of sessions we need to indicate the name of the resource and the corresponding URL:2

2. A second option is to use form_tag in place of form_for, which might be even more idiomatically correct Rails, but it has less in common with the signup form, and at this stage I want to emphasize the parallel structure.

form_for(:session, url: login_path)

With the proper form_for in hand, it’s easy to make a login form to match the mockup in Figure 8.1 using the signup form (Listing 7.15) as a model, as shown in Listing 8.4.

Listing 8.4: Code for the login form.

app/views/sessions/new.html.erb

<% provide(:title, "Log in") %>

<h1>Log in</h1>

<div class="row">

<div class="col-md-6 col-md-offset-3">

<%= form_for(:session, url: login_path) do |f| %>

<%= f.label :email %>

<%= f.email_field :email, class: 'form-control' %>

<%= f.label :password %>

<%= f.password_field :password, class: 'form-control' %>

<%= f.submit "Log in", class: "btn btn-primary" %>

<% end %>

<p>New user? <%= link_to "Sign up now!", signup_path %></p>

</div>

</div>

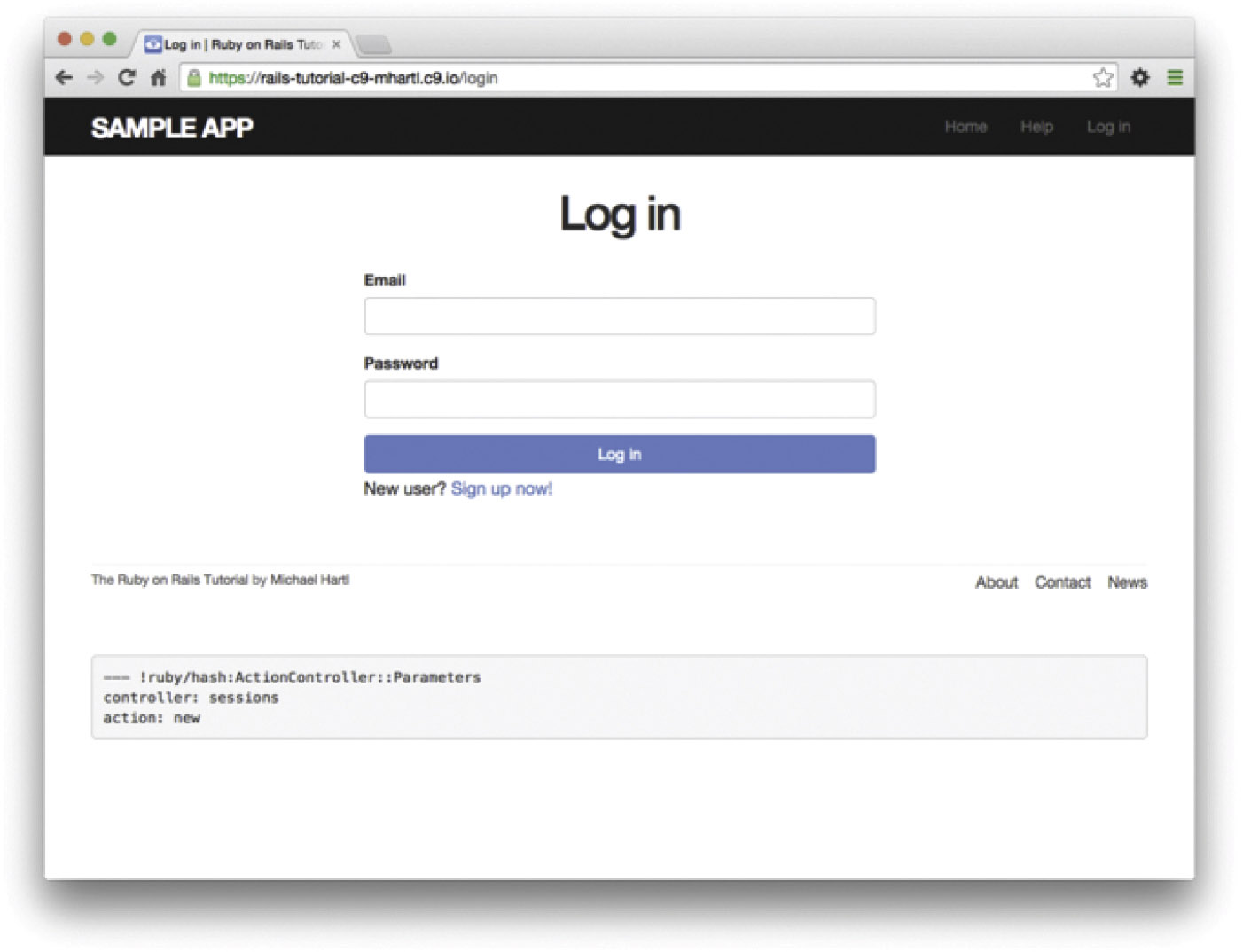

Note that we’ve added a link to the signup page for convenience. With the code in Listing 8.4, the login form appears as in Figure 8.3. (Because the “Log in” navigation link hasn’t yet been filled in, you’ll have to type the /login URL directly into your address bar. We’ll fix this blemish in Section 8.2.3.)

The generated form HTML appears in Listing 8.5.

Listing 8.5: HTML for the login form produced by Listing 8.4.

<form accept-charset="UTF-8" action="/login" method="post">

<input name="utf8" type="hidden" value="✓" />

<input name="authenticity_token" type="hidden"

value="NNb6+J/j46LcrgYUC60wQ2titMuJQ5lLqyAbnbAUkdo=" />

<label for="session_email">Email</label>

<input class="form-control" id="session_email"

name="session[email]" type="text" />

<label for="session_password">Password</label>

<input id="session_password" name="session[password]"

type="password" />

<input class="btn btn-primary" name="commit" type="submit"

value="Log in" />

</form>

Comparing Listing 8.5 with Listing 7.17, you might be able to guess that submitting this form will result in a params hash where params[:session][:email] and params[:session][:password] correspond to the email and password fields.

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. Submissions from the form defined in Listing 8.4 will be routed to the Session controller’s create action. How does Rails know to do this? Hint: Refer to Table 8.1 and the first line of Listing 8.5.

8.1.3 Finding and Authenticating a User

As in the case of creating users (signup), the first step in creating sessions (login) is to handle invalid input. We’ll start by reviewing what happens when a form gets submitted, and then arrange for helpful error messages to appear in the case of login failure (as mocked up in Figure 8.2). Then we’ll lay the foundation for successful login (Section 8.2) by evaluating each login submission based on the validity of its email/password combination.

Let’s start by defining a minimalist create action for the Sessions controller, along with empty new and destroy actions (Listing 8.6). The create action in Listing 8.6 does nothing but render the new view, but it’s enough to get us started. Submitting the /sessions/new form then yields the result shown in Figure 8.4.

Listing 8.6: A preliminary version of the Sessions create action.

app/controllers/sessions_controller.rb

class SessionsController < ApplicationController

def new

end

def create

render 'new'

end

def destroy

end

end

Carefully inspecting the debug information in Figure 8.4 shows that, as hinted at the end of Section 8.1.2, the submission results in a params hash containing the email and password under the key session, which (omitting some irrelevant details used internally by Rails) appears as follows:

---

session:

email: '[email protected]'

password: 'foobar'

commit: Log in

action: create

controller: sessions

As with the case of user signup (Figure 7.15), these parameters form a nested hash like the one we saw in Listing 4.13. In particular, params contains a nested hash of the form

{ session: { password: "foobar", email: "[email protected]" } }

Figure 8.4: The initial failed login, with create as in Listing 8.6.

This means that

params[:session]

is itself a hash:

{ password: "foobar", email: "[email protected]" }

As a result,

params[:session][:email]

is the submitted email address and

params[:session][:password]

is the submitted password.

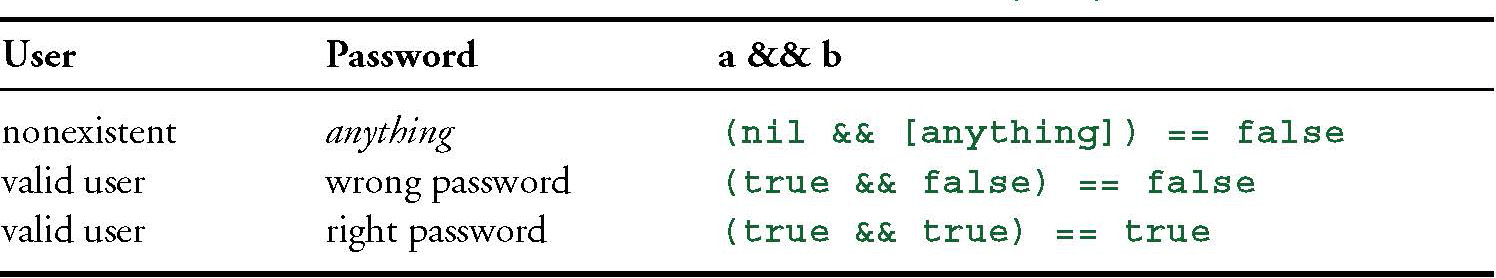

In other words, inside the create action the params hash has all the information needed to authenticate users by email and password. Not coincidentally, we already have exactly the methods we need: the User.find_by method provided by Active Record (Section 6.1.4) and the authenticate method provided by has_secure_ password (Section 6.3.4). Recalling that authenticate returns false for an invalid authentication (Section 6.3.4), our strategy for user login can be summarized as shown in Listing 8.7.

Listing 8.7: Finding and authenticating a user.

app/controllers/sessions_controller.rb

class SessionsController < ApplicationController

def new

end

def create

user = User.find_by(email: params[:session][:email].downcase)

if user && user.authenticate(params[:session][:password])

# Log the user in and redirect to the user's show page.

else

# Create an error message.

render 'new'

end

end

def destroy

end

end

The first highlighted line in Listing 8.7 pulls the user out of the database using the submitted email address. (Recall from Section 6.2.5 that email addresses are saved as all lowercase, so here we use the downcase method to ensure a match when the submitted address is valid.) The next line can be a bit confusing but is fairly common in idiomatic Rails programming:

user && user.authenticate(params[:session][:password])

This uses && (logical and) to determine if the resulting user is valid. Taking into account that any object other than nil and false itself is true in a boolean context (Section 4.2.3), the possibilities appear as in Table 8.2. We see from Table 8.2 that the if statement is true only if a user with the given email both exists in the database and has the given password, exactly as required.

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. Using the Rails console, confirm each of the values in Table 8.2. Start with user = nil, and then use user = User.first. Hint: To coerce the result to a boolean value, use the bang-bang trick from Section 4.2.3, as in !! (user && user.authenticate('foobar')).

8.1.4 Rendering with a Flash Message

Recall from Section 7.3.3 that we displayed signup errors using the User model error messages. These errors are associated with a particular Active Record object, but this strategy won’t work here because the session isn’t an Active Record model. Instead, we’ll put a message in the flash to be displayed upon failed login. A first, slightly incorrect, attempt appears in Listing 8.8.

Listing 8.8: An (unsuccessful) attempt at handling failed login.

app/controllers/sessions_controller.rb

class SessionsController < ApplicationController

def new

end

def create

user = User.find_by(email: params[:session][:email].downcase)

if user && user.authenticate(params[:session][:password])

# Log the user in and redirect to the user's show page.

else

flash[:danger] = 'Invalid email/password combination' # Not quite right!

render 'new'

end

end

def destroy

end

end

Because of the flash message display in the site layout (Listing 7.31), the flash[:danger] message automatically gets displayed; because of the Bootstrap CSS, it automatically gets nice styling (Figure 8.5).

Unfortunately, as noted in the text and in the comment in Listing 8.8, this code isn’t quite right. The page looks fine, though, so what’s the problem? The issue is that the contents of the flash persist for one request, but—unlike a redirect, which we used in Listing 7.29—re-rendering a template with render doesn’t count as a request. The result is that the flash message persists one request longer than we want. For example, if we submit invalid login information and then click on the Home page, the flash gets displayed a second time (Figure 8.6). Fixing this blemish is the task of Section 8.1.5.

8.1.5 A Flash Test

The incorrect flash behavior is a minor bug in our application. According to the testing guidelines from Box 3.3, this is exactly the sort of situation where we should write a test to catch the error so that it doesn’t recur. We’ll thus write a short integration test for the login form submission before proceeding. In addition to documenting the bug and preventing a regression, this will also give us a good foundation for further integration tests of login and logout.

We start by generating an integration test for our application’s login behavior:

$ rails generate integration_test users_login

invoke test_unit

create test/integration/users_login_test.rb

Next, we need a test to capture the sequence shown in Figure 8.5 and Figure 8.6. The basic steps appear as follows:

1. Visit the login path.

2. Verify that the new sessions form renders properly.

3. Post to the sessions path with an invalid params hash.

4. Verify that the new sessions form gets re-rendered and that a flash message appears.

5. Visit another page (such as the Home page).

6. Verify that the flash message doesn’t appear on the new page.

A test implementing the above steps appears in Listing 8.9.

Listing 8.9: A test to catch unwanted flash persistence. RED

test/integration/users_login_test.rb

require 'test_helper'

class UsersLoginTest < ActionDispatch::IntegrationTest

test "login with invalid information" do

get login_path

assert_template 'sessions/new'

post login_path, params: { session: { email: "", password: "" } }

assert_template 'sessions/new'

assert_not flash.empty?

get root_path

assert flash.empty?

end

end

After adding the test in Listing 8.9, the login test should be RED:

$ rails test test/integration/users_login_test.rb

This shows how to run one (and only one) test file using rails test and the full path to the file.

The way to get the failing test in Listing 8.9 to pass is to replace flash with the special variant flash.now, which is specifically designed for displaying flash messages on rendered pages. Unlike the contents of flash, the contents of flash.now disappear as soon as there is an additional request, which is exactly the behavior we’ve tested in Listing 8.9. With this substitution, the corrected application code appears as in Listing 8.11.

Listing 8.11: Correct code for failed login. GREEN

app/controllers/sessions_controller.rb

class SessionsController < ApplicationController

def new

end

def create

user = User.find_by(email: params[:session][:email].downcase)

if user && user.authenticate(params[:session][:password])

# Log the user in and redirect to the user's show page.

else

flash.now[:danger] = 'Invalid email/password combination'

render 'new'

end

end

def destroy

end

end

We can then verify that both the login integration test and the full test suite are GREEN:

$ rails test test/integration/users_login_test.rb

$ rails test

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. Verify in your browser that the sequence from Section 8.1.4 works correctly, i.e., that the flash message disappears when you click on a second page.

8.2 Logging In

Now that our login form can handle invalid submissions, the next step is to handle valid submissions correctly by actually logging a user in. In this section, we’ll log the user in with a temporary session cookie that expires automatically upon browser close. In Section 9.1, we’ll add sessions that persist even after closing the browser.

Implementing sessions will involve defining a large number of related functions for use across multiple controllers and views. You may recall from Section 4.2.5 that Ruby provides a module facility for packaging such functions in one place. Conveniently, a Sessions helper module was generated automatically when generating the Sessions controller (Section 8.1.1). Moreover, such helpers are automatically included in Rails views; by including the module into the base class of all controllers (the Application controller), we arrange to make them available in our controllers as well (Listing 8.13).3

3. I like this technique because it connects to the pure Ruby way of including modules, but Rails 4 introduced a technique called concerns that can also be used for this purpose. To learn how to use concerns, run a search for “how to use concerns in Rails”.

Listing 8.13: Including the Sessions helper module into the Application

controller.

app/controllers/application_controller.rb

class ApplicationController < ActionController::Base

protect_from_forgery with: :exception

include SessionsHelper

end

With this configuration complete, we’re now ready to write the code to log users in.

8.2.1 The log_in Method

Logging a user in is simple with the help of the session method defined by Rails. (This method is separate and distinct from the Sessions controller generated in Section 8.1.1.) We can treat session as if it were a hash and assign to it as follows:

session[:user_id] = user.id

This places a temporary cookie on the user’s browser containing an encrypted version of the user’s id, which allows us to retrieve the id on subsequent pages using session[:user_id]. In contrast to the persistent cookie created by the cookies method (Section 9.1), the temporary cookie created by the session method expires immediately when the browser is closed.

Because we’ll want to use the same login technique in a couple of different places, we’ll define a method called log_in in the Sessions helper, as shown in Listing 8.14.

Listing 8.14: The log_in function.

app/helpers/sessions_helper.rb

module SessionsHelper

# Logs in the given user.

def log_in(user)

session[:user_id] = user.id

end

end

Because temporary cookies created using the session method are automatically encrypted, the code in Listing 8.14 is secure, and there is no way for an attacker to use the session information to log in as the user. This applies only to temporary sessions initiated with the session method, though, and is not the case for persistent sessions created using the cookies method. Permanent cookies are vulnerable to a session hijacking attack, so in Chapter 9 we’ll have to be much more careful about the information we place on the user’s browser.

With the log_in method defined in Listing 8.14, we’re now ready to complete the session create action by logging the user in and redirecting to the user’s profile page. The result appears in Listing 8.15.4

4. The log_in method is available in the Sessions controller because of the module inclusion in Listing 8.13.

Listing 8.15: Logging in a user.

app/controllers/sessions_controller.rb

class SessionsController < ApplicationController

def new

end

def create

user = User.find_by(email: params[:session][:email].downcase)

if user && user.authenticate(params[:session][:password])

log_in user

redirect_to user

else

flash.now[:danger] = 'Invalid email/password combination'

render 'new'

end

end

def destroy

end

end

Note the compact redirect

redirect_to user

which we saw before in Section 7.4.1. Rails automatically converts this to the route for the user’s profile page:

user_url(user)

With the create action defined in Listing 8.15, the login form defined in Listing 8.4 should now be working. It doesn’t have any effects on the application display, though, so short of inspecting the browser session directly, there’s no way to tell that you’re logged in. As a first step toward enabling more visible changes, in Section 8.2.2 we’ll retrieve the current user from the database using the id in the session. In Section 8.2.3, we’ll change the links on the application layout, including a URL to the current user’s profile.

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. Log in with a valid user and inspect your browser’s cookies. What is the value of the session content? Hint: If you don’t know how to view your browser’s cookies, Google for it (Box 1.1).

2. What is the value of the Expires attribute from the previous exercise?

8.2.2 Current User

Having placed the user’s id securely in the temporary session, we are now in a position to retrieve it on subsequent pages, which we’ll do by defining a current_user method to find the user in the database corresponding to the session id. The purpose of current_user is to allow constructions such as

<%= current_user.name %>

and

redirect_to current_user

To find the current user, one possibility is to use the find method, as on the user profile page (Listing 7.5):

User.find(session[:user_id])

But recall from Section 6.1.4 that find raises an exception if the user id doesn’t exist. This behavior is appropriate on the user profile page because it will only happen if the id is invalid, but in the present case session[:user_id] will often be nil (i.e., for non-logged-in users). To handle this possibility, we’ll use the same find_by method used to find by email address in the create method, with id in place of email:

User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

Rather than raising an exception, this method returns nil (indicating no such user) if the id is invalid.

We could now define the current_user method as follows:

def current_user

User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

end

This would work fine, but it would hit the database multiple times if, e.g., current_user appeared multiple times on a page. Instead, we’ll follow a common Ruby convention by storing the result of User.find_by in an instance variable, which hits the database the first time but returns the instance variable immediately on subsequent invocations:5

5. This practice of remembering variable assignments from one method invocation to the next is known as memoization. (Note that this is a technical term; in particular, it’s not a misspelling of “memorization”—a subtlety lost on the hapless copyeditor of a previous edition of this book.)

if @current_user.nil?

@current_user = User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

else

@current_user

end

Recalling the or operator || seen in Section 4.2.3, we can rewrite this as follows:

@current_user = @current_user || User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

Because a User object is true in a boolean context, the call to find_by only gets executed if @current_user hasn’t yet been assigned.

Although the preceding code would work, it’s not idiomatically correct Ruby; instead, the proper way to write the assignment to @current_user is like this:

@current_user ||= User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

This uses the potentially confusing but frequently used ||= (“or equals”) operator (Box 8.1).

Applying the results of the above discussion yields the succinct current_ user method shown in Listing 8.16.

Listing 8.16: Finding the current user in the session.

app/helpers/sessions_helper.rb

module SessionsHelper

# Logs in the given user.

def log_in(user)

session[:user_id] = user.id

end

# Returns the current logged-in user (if any).

def current_user

@current_user ||= User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

end

end

With the working current_user method in Listing 8.16, we’re now in a position to make changes to our application based on user login status.

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. Confirm at the console that User.find_by(id: ...) returns nil when the corresponding user doesn’t exist.

2. In a Rails console, create a session hash with key :user_id. By following the steps in Listing 8.17, confirm that the ||= operator works as required.

Listing 8.17: Simulating session in the console.

>> session = {}

>> session[:user_id] = nil

>> @current_user ||= User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

<What happens here?>

>> session[:user_id]= User.first.id

>> @current_user ||= User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

<What happens here?>

>> @current_user ||= User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

<What happens here?>

8.2.3 Changing the Layout Links

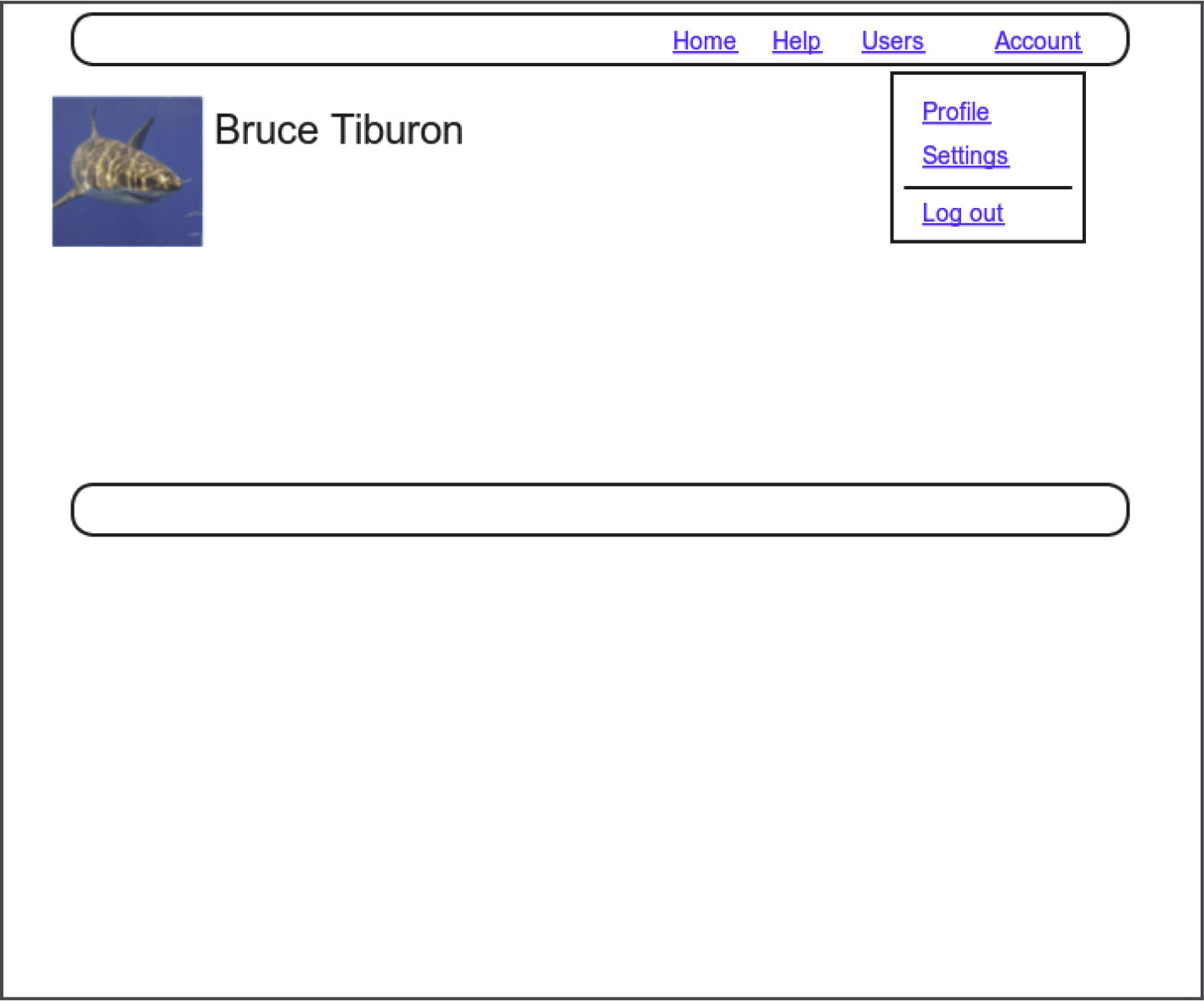

The first practical application of logging in involves changing the layout links based on login status. In particular, as seen in the Figure 8.7 mockup,6 we’ll add links for logging out, for user settings, for listing all users, and for the current user’s profile page. Note in Figure 8.7 that the logout and profile links appear in a dropdown “Account” menu; we’ll see in Listing 8.19 how to make such a menu with Bootstrap.

6. Image retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/elevy/14730820387 on 2016-06-03. Copyright © 2014 by Elias Levy and used unaltered under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

At this point, in real life I would consider writing an integration test to capture the behavior described above. As noted in Box 3.3, as you become more familiar with the testing tools in Rails you may find yourself more inclined to write tests first. In this case, though, such a test involves several new ideas, so for now it’s best deferred to its own section (Section 8.2.4).

The way to change the links in the site layout involves using an if-else statement inside embedded Ruby to show one set of links if the user is logged in and another set of links otherwise:

<% if logged_in? %>

# Links for logged-in users

<% else %>

# Links for non-logged-in-users

<% end %>

This kind of code requires the existence of a logged_in? boolean method, which we’ll now define.

A user is logged in if there is a current user in the session, i.e., if current_ user is not nil. Checking for this requires the use of the “not” operator (Section 4.2.3), written using an exclamation point ! and usually read as “bang”. The resulting logged_in? method appears in Listing 8.18.

Listing 8.18: The logged_in? helper method.

app/helpers/sessions_helper.rb

module SessionsHelper

# Logs in the given user.

def log_in(user)

session[:user_id] = user.id

end

# Returns the current logged-in user (if any).

def current_user

@current_user ||= User.find_by(id: session[:user_id])

end

# Returns true if the user is logged in, false otherwise.

def logged_in?

!current_user.nil?

end

end

With the addition in Listing 8.18, we’re now ready to change the layout links if a user is logged in. There are four new links, two of which are stubbed out (to be completed in Chapter 10):

<%= link_to "Users", '#' %>

<%= link_to "Settings", '#' %>

The logout link, meanwhile, uses the logout path defined in Listing 8.2:

<%= link_to "Log out", logout_path, method: :delete %>

Notice that the logout link passes a hash argument indicating that it should submit with an HTTP DELETE request.7 We’ll also add a profile link as follows:

7. Web browsers can’t actually issue DELETE requests; Rails fakes it with JavaScript.

<%= link_to "Profile", current_user %>

Here we could write

<%= link_to "Profile", user_path(current_user) %>

but as usual Rails allows us to link directly to the user by automatically converting current_user into user_path(current_user) in this context. Finally, when users aren’t logged in, we’ll use the login path defined in Listing 8.2 to make a link to the login form:

<%= link_to "Log in", login_path %>

Putting everything together gives the updated header partial shown in Listing 8.19.

Listing 8.19: Changing the layout links for logged-in users.

app/views/layouts/_header.html.erb

<header class="navbar navbar-fixed-top navbar-inverse">

<div class="container">

<%= link_to "sample app", root_path, id: "logo" %>

<nav>

<ul class="nav navbar-nav navbar-right">

<li><%= link_to "Home", root_path %></li>

<li><%= link_to "Help", help_path %></li>

<% if logged_in? %>

<li><%= link_to "Users", "#" %></li>

<li class="dropdown">

<a href="#" class="dropdown-toggle" data-toggle="dropdown">

Account <b class="caret"></b>

</a>

<ul class="dropdown-menu">

<li><%= link_to "Profile", current_user %></li>

<li><%= link_to "Settings", "#" %></li>

<li class="divider"></li>

<li>

<%= link_to "Log out", logout_path, method: "delete" %>

</li>

</ul>

</li>

<% else %>

<li><%= link_to "Log in", login_path %></li>

<% end %>

</ul>

</nav>

</div>

</header>

As part of including the new links into the layout, Listing 8.19 takes advantage of Bootstrap’s ability to make dropdown menus.8 Note in particular the inclusion of the special Bootstrap CSS classes such as dropdown, dropdown-menu, etc. To activate the dropdown menu, we need to include Bootstrap’s custom JavaScript library in the Rails asset pipeline’s application.js file, as shown in Listing 8.20.

8. See the Bootstrap components page for more information.

Listing 8.20: Adding the Bootstrap JavaScript library to application.js.

app/assets/javascripts/application.js

//= require jquery

//= require jquery_ujs

//= require bootstrap

//= require turbolinks

//= require_tree .

At this point, you should visit the login path and log in as a valid user (username [email protected], password foobar), which effectively tests the code in the previous three sections.9 With the code in Listing 8.19 and Listing 8.20, you should see the dropdown menu and links for logged-in users, as shown in Figure 8.8.

9. You may have to restart the webserver to get this to work (Box 1.1).

If you quit your browser completely, you should also be able to verify that the application forgets your login status, requiring you to log in again to see the changes described above.10

10. If you’re using the cloud IDE, I recommend using a different browser to test the login behavior so that you don’t have to close down the browser running the IDE.

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. Using the cookie inspector in your browser (Section 8.2.1), remove the session cookie and confirm that the layout links revert to the non-logged-in state.

2. Log in again, confirming that the layout links change correctly. Then quit your browser and start it again to confirm that the layout links revert to the non-logged-in state. (If your browser has a “remember where I left off ” feature that automatically restores the session, be sure to disable it in this step [Box 1.1].)

8.2.4 Testing Layout Changes

Having verified by hand that the application is behaving properly upon successful login, before moving on we’ll write an integration test to capture that behavior and catch regressions. We’ll build on the test from Listing 8.9 and write a series of steps to verify the following sequence of actions:

1. Visit the login path.

2. Post valid information to the sessions path.

3. Verify that the login link disappears.

4. Verify that a logout link appears

5. Verify that a profile link appears.

In order to see these changes, our test needs to log in as a previously registered user, which means that such a user must already exist in the database. The default Rails way to do this is to use fixtures, which are a way of organizing data to be loaded into the test database. We discovered in Section 6.2.5 that we needed to delete the default fixtures so that our email uniqueness tests would pass (Listing 6.31). Now we’re ready to start filling in that empty file with custom fixtures of our own.

In the present case, we need only one user, whose information should consist of a valid name and email address. Because we’ll need to log the user in, we also have to include a valid password to compare with the password submitted to the Sessions controller’s create action. Referring to the data model in Figure 6.8, we see that this means creating a password_digest attribute for the user fixture, which we’ll accomplish by defining a digest method of our own.

As discussed in Section 6.3.1, the password digest is created using bcrypt (via has_secure_password), so we’ll need to create the fixture password using the same method. By inspecting the secure password source code, we find that this method is

BCrypt::Password.create(string, cost: cost)

where string is the string to be hashed and cost is the cost parameter that determines the computational cost to calculate the hash. Using a high cost makes it computationally intractable to use the hash to determine the original password, which is an important security precaution in a production environment, but in tests we want the digest method to be as fast as possible. The secure password source code has a line for this as well:

cost = ActiveModel::SecurePassword.min_cost ? BCrypt::Engine::MIN_COST :

BCrypt::Engine.cost

This rather obscure code, which you don’t need to understand in detail, arranges for precisely the behavior described above: it uses the minimum cost parameter in tests and a normal (high) cost parameter in production. (We’ll learn more about the strange ?-: notation in Section 9.2.)

There are several places we could put the resulting digest method, but we’ll have an opportunity in Section 9.1.1 to reuse digest in the User model. This suggests placing the method in user.rb. Because we won’t necessarily have access to a user object when calculating the digest (as will be the case in the fixtures file), we’ll attach the digest method to the User class itself, which (as we saw briefly in Section 4.4.1) makes it a class method. The result appears in Listing 8.21.

Listing 8.21: Adding a digest method for use in fixtures.

app/models/user.rb

class User < ApplicationRecord

before_save { self.email = email.downcase }

validates :name, presence: true, length: { maximum: 50 }

VALID_EMAIL_REGEX = /A[w+-.]+@[a-zd-.]+.[a-z]+z/i

validates :email, presence: true, length: { maximum: 255 },

format: { with: VALID_EMAIL_REGEX },

uniqueness: { case_sensitive: false }

has_secure_password

validates :password, presence: true, length: { minimum: 6 }

# Returns the hash digest of the given string.

def User.digest(string)

cost = ActiveModel::SecurePassword.min_cost ? BCrypt::Engine::MIN_COST :

BCrypt::Engine.cost

BCrypt::Password.create(string, cost: cost)

end

end

With the digest method from Listing 8.21, we are now ready to create a user fixture for a valid user, as shown in Listing 8.22.11

11. It’s worth noting that indentation in fixture files must take the form of spaces, not tabs, so take care when copying code like that shown in Listing 8.22.

Listing 8.22: A fixture for testing user login.

test/fixtures/users.yml

michael:

name: Michael Example

email: [email protected]

password_digest: <%= User.digest('password') %>

Note in particular that fixtures support embedded Ruby, which allows us to use

<%= User.digest('password') %>

to create the valid password digest for the test user.

Although we’ve defined the password_digest attribute required by has_ secure_password, sometimes it’s convenient to refer to the plain (virtual) password as well. Unfortunately, this is impossible to arrange with fixtures, and adding a password attribute to Listing 8.22 causes Rails to complain that there is no such column in the database (which is true). We’ll make do by adopting the convention that all fixture users have the same password ('password').

Having created a fixture with a valid user, we can retrieve it inside a test as follows:

user = users(:michael)

Here users corresponds to the fixture filename users.yml, while the symbol

:michael references user with the key shown in Listing 8.22.

With the fixture user as above, we can now write a test for the layout links by converting the sequence enumerated at the beginning of this section into code, as shown in Listing 8.23.

Listing 8.23: A test for user logging in with valid information. GREEN

test/integration/users_login_test.rb

require 'test_helper'

class UsersLoginTest < ActionDispatch::IntegrationTest

def setup

@user = users(:michael)

end

.

.

.

test "login with valid information" do

get login_path

post login_path, params: { session: { email: @user.email,

password: 'password' } }

assert_redirected_to @user

follow_redirect!

assert_template 'users/show'

assert_select "a[href=?]", login_path, count: 0

assert_select "a[href=?]", logout_path

assert_select "a[href=?]", user_path(@user)

end

end

assert_redirected_to @user

to check the right redirect target and

follow_redirect!

to actually visit the target page. Listing 8.23 also verifies that the login link disappears by verifying that there are zero login path links on the page:

assert_select "a[href=?]", login_path, count: 0

By including the extra count: 0 option, we tell assert_select that we expect there to be zero links matching the given pattern. (Compare this to count: 2 in Listing 5.32, which checks for exactly two matching links.)

Because the application code was already working, this test should be GREEN:

$ rails test test/integration/users_login_test.rb

> --name test_login_with_valid_information

This shows how to run a specific test within a test file by passing the option

--name test_login_with_valid_information

containing the name of the test. (A test’s name is just the word “test” and the words in the test description joined using underscores.) Note that the > on the second line is a “line continuation” character inserted automatically by the shell and should not be typed literally.

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. Delete the bang ! in the Session helper’s logged_in? method and confirm that the test in Listing 8.23 is RED.

2. Restore the ! to get back to GREEN.

8.2.5 Login Upon Signup

Although our authentication system is now working, newly registered users might be confused, as they are not logged in by default. Because it would be strange to force users to log in immediately after signing up, we’ll log in new users automatically as part of the signup process. To arrange this behavior, all we need to do is add a call to log_in in the Users controller create action, as shown in Listing 8.25.12

12. As with the Sessions controller, the log_in method is available in the Users controller because of the module inclusion in Listing 8.13.

Listing 8.25: Logging in the user upon signup.

app/controllers/users_controller.rb

class UsersController < ApplicationController

def show

@user = User.find(params[:id])

end

def new

@user = User.new

end

def create

@user = User.new(user_params)

if @user.save

log_in @user

flash[:success] = "Welcome to the Sample App!"

redirect_to @user

else

render 'new'

end

end

private

def user_params

params.require(:user).permit(:name, :email, :password,

:password_confirmation)

end

end

To test the behavior from Listing 8.25, we can add a line to the test from Listing 7.33 to check that the user is logged in. It’s helpful in this context to define an is_logged_in? helper method to parallel the logged_in? helper defined in Listing 8.18, which returns true if there’s a user id in the (test) session and false otherwise (Listing 8.26). (Because helper methods aren’t available in tests, we can’t use the current_user as in Listing 8.18, but the session method is available, so we use that instead.) Here we use is_logged_in? instead of logged_in? so that the test helper and Sessions helper methods have different names, which prevents them from being mistaken for each other.13

13. For example, I once had a test suite that was GREEN even after accidentally deleting the main log_in method in the Sessions helper. The reason is that the tests were happily using a test helper with the same name, thereby passing even though the application was completely broken. As with is_logged_in?, we’ll avoid this issue by defining the test helper log_in_as in Listing 9.24.

Listing 8.26: A boolean method for login status inside tests.

test/test_helper.rb

ENV['RAILS_ENV'] ||= 'test'

.

.

.

class ActiveSupport::TestCase

fixtures :all

# Returns true if a test user is logged in.

def is_logged_in?

!session[:user_id].nil?

end

end

With the code in Listing 8.26, we can assert that the user is logged in after signup using the line shown in Listing 8.27.

Listing 8.27: A test of login after signup. GREEN

test/integration/users_signup_test.rb

require 'test_helper'

class UsersSignupTest < ActionDispatch::IntegrationTest

.

.

.

test "valid signup information" do

get signup_path

assert_difference 'User.count', 1 do

post users_path, params: { user: { name: "Example User",

email: "[email protected]",

password: "password",

password_confirmation: "password" } }

end

follow_redirect!

assert_template 'users/show'

assert is_logged_in?

end

end

At this point, the test suite should still be GREEN:

$ rails test

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. Is the test suite RED or GREEN if you comment out the log_in line in Listing 8.25?

2. By using your text editor’s ability to comment out code, toggle back and forth between commenting out code in Listing 8.25 and confirm that the test suite toggles between RED and GREEN. (You will need to save the file between toggles.)

8.3 Logging Out

As discussed in Section 8.1, our authentication model is to keep users logged in until they log out explicitly. In this section, we’ll add this necessary logout capability. Because the “Log out” link has already been defined (Listing 8.19), all we need is to write a valid controller action to destroy user sessions.

So far, the Sessions controller actions have followed the RESTful convention of using new for a login page and create to complete the login. We’ll continue this theme by using a destroy action to delete sessions, i.e., to log out. Unlike the login functionality, which we use in both Listing 8.15 and Listing 8.25, we’ll only be logging out in one place, so we’ll put the relevant code directly in the destroy action. As we’ll see in Section 9.3, this design (with a little refactoring) will also make the authentication machinery easier to test.

Logging out involves undoing the effects of the log_in method from Listing 8.14, which involves deleting the user id from the session.14 To do this, we use the delete method as follows:

14. Some browsers offer a “remember where I left off” feature, which restores the session automatically, so be sure to disable any such feature before trying to log out.

session.delete(:user_id)

We’ll also set the current user to nil, although in the present case this won’t matter because of an immediate redirect to the root URL.15 As with log_in and associated methods, we’ll put the resulting log_out method in the Sessions helper module, as shown in Listing 8.29.

15. Setting @current_user to nil would only matter if @current_user were created before the destroy action (which it isn’t) and if we didn’t issue an immediate redirect (which we do). This is an unlikely combination of events, and with the application as presently constructed it isn’t necessary, but because it’s security-related I include it for completeness.

Listing 8.29: The log_out method.

app/helpers/sessions_helper.rb

module SessionsHelper

# Logs in the given user.

def log_in(user)

session[:user_id] = user.id

end

.

.

.

# Logs out the current user.

def log_out

session.delete(:user_id)

@current_user = nil

end

end

We can put the log_out method to use in the Sessions controller’s destroy action, as shown in Listing 8.30.

Listing 8.30: Destroying a session (user logout).

app/controllers/sessions_controller.rb

class SessionsController < ApplicationController

def new

end

def create

user = User.find_by(email: params[:session][:email].downcase)

if user && user.authenticate(params[:session][:password])

log_in user

redirect_to user

else

flash.now[:danger] = 'Invalid email/password combination'

render 'new'

end

end

def destroy

log_out

redirect_to root_url

end

end

To test the logout machinery, we can add some steps to the user login test from Listing 8.23. After logging in, we use delete to issue a DELETE request to the logout path (Table 8.1) and verify that the user is logged out and redirected to the root URL. We also check that the login link reappears and that the logout and profile links disappear. The new steps appear in Listing 8.31.

Listing 8.31: A test for user logout. GREEN

test/integration/users_login_test.rb

require 'test_helper'

class UsersLoginTest < ActionDispatch::IntegrationTest

.

.

.

test "login with valid information followed by logout" do

get login_path

post login_path, params: { session: { email: @user.email,

password: 'password' } }

assert is_logged_in?

assert_redirected_to @user

follow_redirect!

assert_template 'users/show'

assert_select "a[href=?]", login_path, count: 0

assert_select "a[href=?]", logout_path

assert_select "a[href=?]", user_path(@user)

delete logout_path

assert_not is_logged_in?

assert_redirected_to root_url

follow_redirect!

assert_select "a[href=?]", login_path

assert_select "a[href=?]", logout_path, count: 0

assert_select "a[href=?]", user_path(@user), count: 0

end

end

(Now that we have is_logged_in? available in tests, we’ve also thrown in a bonus assert is_logged_in? immediately after posting valid information to the sessions path.)

With the session destroy action thus defined and tested, the initial signup/login/ logout triumvirate is complete, and the test suite should be GREEN:

$ rails test

Exercises

Solutions to exercises are available for free at railstutorial.org/solutions with any Rails Tutorial purchase. To see other people’s answers and to record your own, join the Learn Enough Society at learnenough.com/society.

1. Confirm in a browser that the “Log out” link causes the correct changes in the site layout. What is the correspondence between these changes and the final three steps in Listing 8.31?

2. By checking the site cookies, confirm that the session is correctly removed after logging out.

8.4 Conclusion

With the material in this chapter, our sample application has a fully functional login and authentication system. In the next chapter, we’ll take our app to the next level by adding the ability to remember users for longer than a single browser session.

Before moving on, merge your changes back into the master branch:

$ rails test

$ git add -A

$ git commit -m "Implement basic login"

$ git checkout master

$ git merge basic-login

Then push up to the remote repository:

$ rails test

$ git push

Finally, deploy to Heroku as usual:

$ git push heroku

8.4.1 What We Learned in This Chapter

• Rails can maintain state from one page to the next using temporary cookies via the session method.

• The login form is designed to create a new session to log a user in.

• The flash.now method is used for flash messages on rendered pages.

• Test-driven development is useful when debugging by reproducing the bug in a test.

• Using the session method, we can securely place a user id on the browser to create a temporary session.

• We can change features such as links on the layouts based on login status.

• Integration tests can verify correct routes, database updates, and proper changes to the layout.