2

Culture of Shared Responsibility

“Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

This quote from management expert Peter Drucker emphasized the impact culture has on what organizations strive to achieve. In the previous chapter, we saw how culture (people, their behavior, and the structures that encourage their behavior in organizations) provides the underpinnings of processes and tools. So, if culture is so important, what’s the best culture and how do we attain that if we find that our present culture is lacking?

We find that structure and behavior will determine culture. We will first examine different cultures based on a classic organizational culture model. This examination of organizational cultures will include traits and characteristics and how each handles information flow. We then look at how to effect cultural change toward a more desired culture by changing behavior.

Armed with this knowledge of the ideal organizational culture and how to effect change, we will examine the structure of culture that the SAFe® promotes. The first part is identifying how both Lean thinking and the Agile Manifesto play a role in developing the proper mindset.

With this mindset at play, we will take a close look at the principles in SAFe® that provide context not only to the structure but also to the practices put into play to optimize Lean and Agile development.

Finally, we will take an initial look at value streams: the structures that will foster that ideal culture. We will see how value streams build upon the Lean-Agile mindset and SAFe principles to allow for effective cultural change.

In a nutshell, we will be covering the following topics:

- A culture for organizational change

- Lean-Agile mindset

- SAFe principles

- Value streams

A culture for organizational change

Every community of people, from the smallest of teams to the largest of nations, will have a culture—a thread that serves as the identity of the community. A community uses its culture to identify its norms and indicate what makes that community different from other communities.

It is the organization’s responsibility to determine whether its culture is servicing the needs of the organization and allowing it to grow and prosper. The first part of this is the self-inspection of whether the culture is beneficial to the organization. After that analysis, the organization can decide on actions to change the culture.

What kind of culture?

In 1988, Ron Westrum was studying how to improve safety on medical teams when he came upon the idea of examining the culture of those teams. He looked at how these organizations handled information and came up with a typology consisting of three types of cultures. The cultures are identified as the following:

- Pathological

- Bureaucratic

- Generative

According to Westrum, a pathological culture is patterned by a preoccupation with personal power and glory for the organization’s leader. Information is used as leverage for political power. Fear and threats are commonly used as motivation by leaders to accomplish (the leader’s) goals.

In a bureaucratic culture, the organization looks to rules, positions, and departmental turf as its main qualities. Information may be shared through prescribed channels and procedures, but only within local boundaries.

An organization with a generative culture is focused on alignment with the organization’s mission. Information flows freely to whoever can assist with the mission.

Westrum identified examples of the characteristics of how different cultures deal with different kinds of information. These are shown here:

|

Pathological |

Bureaucratic |

Generative | |

|

Focus |

Power-oriented |

Rule-oriented |

Performance-oriented |

|

Cooperation |

Low |

Medium |

High |

|

How do we deal with messengers of bad news |

Blamed |

Neglected |

Trained |

|

Handling responsibilities/risks |

Shirked |

Narrowed |

Shared |

|

Communication across organizations |

Discouraged |

Tolerated |

Encouraged |

|

How failure is handled |

Scapegoating |

Seek justice |

Inquiry and learning |

|

How new information is applied |

Crushed |

Discouraged as it may lead to problems |

Implemented |

Table 2.1 – How organizations handle information by culture

A key part of Westrum’s model of information flow dealt with how different cultures handle anomalies or problems discovered. How do organizations react to a negative discovery? Westrum identified six responses, as follows:

- Suppression: Preventing the person from spreading the word about the discovery

- Encapsulation: Ignoring the person who discovered the bad finding

- Public relations: Minimizing the impact of the discovery

- Local fix: Fixing only the immediate problem with no investigation of related issues

- Global fix: Fixing the problem wherever it occurs

- Inquiry: Thorough investigation of the root cause

The range of responses and the cultures that typically generate them are seen in the following diagram:

Figure 2.1 – Range of responses to anomalies by culture

According to Westrum, the free flow of information in a generative culture fosters three things: alignment, awareness, and empowerment. These three factors are important in setting a mission and working toward goals.

Because information flows freely to all members in a generative culture, awareness comes easily. The organization’s goals are transparent and visible to all. Actions by other members within the organization and outside of the organization are communicated so that dependencies between efforts are effectively managed. So, this awareness is not only local to the organization but also exhibits a broader point of view.

Alignment comes from this awareness by having a visible goal communicated throughout the organization. This allows all people, at all levels in a generative culture, to buy into the goals of the culture.

With a generative culture where everyone knows what the organization’s mission is and all members are aligned toward achieving the organization’s goals, everyone is encouraged to speak up, think outside of their roles and responsibilities, and fully participate in continuous inquiry.

In the end, Westrum concludes that a generative culture, with a free information flow and information processing, allows for fundamental long-lasting improvements to the system as opposed to quick fixes. He notes that culture is mutable and that organizations can move from one type of culture to another.

A generative culture with the traits identified by Westrum has benefits that relate to a development-operations (DevOps) approach. In Accelerate: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations, the authors discovered that an organizational culture that was generative produced higher levels of software delivery performance and organizational performance. In addition, organizations with a generative culture experienced higher levels of job satisfaction.

How do we change the culture?

Culture follows the structure of an organization as well as its behavior. To change an organization’s culture, it stands to reason those changes have to be made both in the structure of the organization and in the behavioral norms that the organization demonstrates.

Although it is important to recognize the values and principles that determine the practices, true behavioral change can only come from applying new practices and allowing continued repetition so that they become habits. When these habits are rewarded and continued, they become a behavior.

One model of fostering the behavioral changes that move cultures comes from Leading Change by John Kotter. In the book, Kotter proposes an eight-step method for driving the transformation of a culture. This method is outlined next.

Creating a sense of urgency

Changing a culture is never easy. People may be set on certain behaviors and unwilling to adopt new behaviors. Often, there needs to be a reason to change, one that is urgent enough to overcome all barriers. These urgent reasons may comprise the following:

- A burning platform: A realization that the current methods have ceased to work and that a change is necessary

- Proactive leadership: New or forward-thinking leadership that is marshaling the change to a better future

In 2006, Ford Motor Company was beset with problems, not only from reduced market share from Japanese and Korean imports but also from internal squabbles. They had lost United States dollars (USD) $17 billion that year and their debts were rated at junk status. Bill Ford, the great-grandson of the founder, Henry Ford, called in Alan Mulally, the current chief executive officer (CEO) of Boeing to see whether he could turn the company around.

Mulally set to work. He created a weekly Business Plan Review (BPR) where leaders would share whether they were green, yellow, or red on their top five business priorities. Every leader indicated they were green until Mulally said: “We are about to lose $17 billion this year, and you are saying that everything is OK? Did we plan to lose $17 billion this year?” His push for transparency shook the leaders at Ford to allow further transformative actions.

Guiding a powerful coalition

People cannot make changes on their own. They need to find or create allies that see the same problems and will align on the changes needed to overcome those problems. These people may have come to the same conclusion or are willing to be early adopters.

As Alan Mulally was getting started as the CEO of Ford, he was determined not to clean the house of the present Ford executives. Some members of his executive team were longstanding employees of Ford who had ideas that meshed with the changes that Mulally was trying to make. Notable additions included Derrick Kuzak, who would become the vice president (VP) of Global Product Development, and Bennie Fowler, the eventual VP of Global Quality.

Creating a vision

What does the future state look like? Which things are important to have in that future state? The idea is not only to understand why change is necessary but what you are changing to. Kotter notes that establishing that vision for change is the responsibility of leadership. Creating a vision serves three purposes, as set out here:

- Mission: This sets the why and provides clarity for everyone

- Motivation: This moves people in the proper direction

- Alignment: The movements of people are coordinated toward the goal

One of the first actions that Alan Mulally detailed was what he wanted the Ford Motor Company to be. He eventually called this plan One Ford. The One Ford plan wanted to accomplish the following:

- Radically restructure Ford’s manufacturing capability to match the capacity to the demand

- Quickly design new vehicles that sated consumer appetites

- Ensure the plan was funded and would ensure economic viability

- Work at a global level as one Ford Motor Company, in contrast to the regional silos at the time

Communicating that vision

Once you have the vision, it’s important that everyone in the organization gets the same message. That message should be clear and free from jargon. Use evocative images and metaphors to fire up imagination. Consistent repetition sets the tone and gives permanence. Be prepared for feedback. Leaders will also be held accountable for behavior that may seem hypocritical in the face of that vision.

Ford had several audiences to which Alan Mulally had to communicate his One Ford vision. He had to broadly send out his message to employees, to the network of Ford dealerships, and to his suppliers and stockholders, which included the descendants of Henry Ford. Mulally accomplished this using several methods, from speeches and press conferences, to make sure each employee received a One Ford wallet card with all the points of that vision.

Empowering others to enact the vision

Once the vision is public, it’s up to those in the organization to determine how to enact that vision. Leaders give them the autonomy to make those behavioral changes and apply new practices that line up with that vision. Leaders can also enable support for such changes including training. Leaders also remove any structural barriers that would encourage resistance or prevent change.

Even as Mulally was preparing his One Ford vision, needed actions were already being accomplished. Mark Fields, then president of the Americas, implemented The Way Forward, which was accelerated when Mulally became CEO. This plan resized Ford by not only closing plants—which allowed Ford to shed inefficient and unprofitable car models—but also re-aligning production lines. Derrick Kuzak set up a new design process called the Global Product Development System (GPDS), which allowed the creation of new car models utilizing a global platform.

Generating short-term wins

The changes will bear fruit. It’s up to leadership to identify and celebrate the wins that emerge, no matter how small. According to Kotter, acknowledging short-term wins has the following effects:

- Provides evidence of the efforts

- Rewards those responsible for the change

- Allows adjustment of the strategies

- Silences cynics and resisters

- Keeps leadership on board

- Builds momentum

Consolidating wins to drive more change

At this point, be careful not to slip into complacency. Work still must be continued; otherwise, the long-term effort will stall. Kotter identified the following hallmarks needed at this point for sustained long-range change:

- More change, not less

- Additional help brought in

- More leadership coming from senior management

- Leadership also coming from further down in the hierarchy

- Eliminating unnecessary interdependencies

As Mulally’s plan to turn around Ford was implemented and started to return results, a global recession caused by the mortgage crisis threatened the entire auto industry. Ford continued with its plan for survival and was the only American auto manufacturer not to accept a government bailout.

Anchoring new changes in the culture

The changes that come and the successes generated are building blocks to a new culture. Each new acknowledgment turns changes into habits and builds habits into desired behavior until it becomes a part of the culture.

The changes introduced by Alan Mulally have stayed with Ford, long after Mulally retired in 2014. The mindset of One Ford still echoes throughout Ford. The development process is a global, unified view as opposed to the regionalized views of different business units (BUs). One of the practices that Mulally introduced, the BPR, spread down from the executive level to teams and is still being used.

Now that we’ve seen a successful way to change to a generative culture, let’s take a closer look at the parts of that culture that an Agile Release Train (ART) will exhibit.

Lean-Agile mindset

An important part of the culture in SAFe that the practices try to engender is a combination of Lean thinking with Agile development. This combination is known as the Lean-Agile mindset.

One of the two parts of this mindset looks at how an organization can eliminate waste to focus on what’s necessary. This part looks at Lean thinking to accomplish that.

The second part of this mindset looks to ensure incremental delivery happens. For this, we look at the Manifesto for Agile Software Development for guidance. Meeting the needs of an organization in SAFe requires a close examination and adjustment of the Agile Manifesto. We’ll soon look at these adjustments.

With this mindset in place, we need to examine what is important in SAFe. To that end, we will examine the core values of SAFe.

The SAFe House of Lean

Lean thinking has its roots in the Toyota Production System (TPS), created by Taiichi Ohno, with some inspiration from W. Edwards Deming. In the TPS, important practices and priorities are arranged like a house, to emphasize the concepts and practices that serve as the foundation, as well as the support. The goal of the TPS serves as the roof:

The SAFe summarizes its Lean thinking approach using a similar House of Lean model paradigm. This model is shown here:

Figure 2.2 – The SAFe House of Lean (©Scaled Agile, Inc. All rights reserved)

Let’s look at each part of this house, as follows:

- The roof (value): The goal we are trying to achieve is value. This value is accomplished in the shortest lead time with the highest quality. This brings delight to the customer and may even change society for the better. Employees benefit from an environment that has high morale and concern for their safety.

- The pillars:

- Respect for people and culture: We look to work in collaboration with others in a generative culture.

- Flow: We look to set up a continuous flow of work so that we can continuously deliver value.

- Innovation: We need time and space to be creative, to let our imaginations soar, and to examine what-if scenarios with our solutions. Without this time and space, our thinking becomes stunted with concern for the next emergency. This is often referred to as tyranny of the urgent.

- Relentless improvement: We look to improve. We understand there is a hidden sense of danger from competition that’s not only established but also represented by the next disruptor that comes with the advent of new technology.

- The foundation (leadership): We cannot set up our house without effective leadership, one that creates a generative culture where everyone has a voice, encourages the flow, sets a time and place for innovation, and looks for opportunities to relentlessly improve.

We’ve seen what’s involved in the Lean aspect of our Lean-Agile mindset. Let’s look at the other half by seeing whether any adjustments need to be made to the Agile Manifesto.

Adjusting the Agile Manifesto

In Chapter 1, Introducing SAFe® and DevOps, we had an initial look at the Agile Manifesto. Given that the original context of the manifesto was initially aimed at small teams of developers, it makes sense that in a differing context of a team of teams, the values and principles may need to be re-examined and adjusted if necessary.

In examining the value statements, we find that the truths that lie with them don’t change with the context. We still value the items on the left more than the items on the right. This is true for a small team or a larger ART.

Some principles may need some further consideration. In particular, SAFe asks you to consider the applicability of principles 2, 4, 6, and 11 from the Agile Manifesto.

Principle 2 of the Agile Manifesto states: “Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.” However, products that use a combination of hardware and software may require balance in accepting changing requirements late in development. Customizable software may allow for changing requirements, but requirement changes that need new hardware may be difficult and costly to fulfill once deployed.

Principle 4 of the Agile Manifesto states: “Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project.” In addition to the Product Owner role that works with the other team members on an Agile team, SAFe includes other roles from the business side. Product Management (PM) works with every team’s Product Owner to define a solution for the ART. Business Owners act as key stakeholders for the ART.

Principle 6 of the Agile Manifesto states: “The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development is face-to-face conversation.” Many of the events held by an ART such as Program Increment (PI) Planning and Inspect and Adapt were originally held primarily as face-to-face events. With the proliferation of globally distributed development and in the face of a historic global pandemic, technological alternatives using web and video conferencing are starting to emerge. As life returns to normal, hybrid methods of meeting and collaborating may emerge.

And finally, Principle 11 of the Agile Manifesto states: “The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.” Here, when developing complex systems of systems, where the ART has 5 to 12 teams, there is a need for balance between 5 to 12 emergent architectures and a single intentional architectural voice. That balance is provided by the System Architect, the role responsible for a product’s architecture and the guide for all the enablers that teams work on.

With the proper mindset identified, we will now take a look at core values important to an ART.

The SAFe core values

SAFe has four important core values enabled by practitioners on an ART with a Lean-Agile mindset. These values are listed here:

- Alignment: In a generative culture with a mission, all participants work together to achieve that mission. An ART that has a generative culture will have teams that will align with other teams on that train.

- Transparency: A generative culture creates transparency by default. This transparency is a key part of ensuring alignment and fostering a generative culture.

- Program execution: The generative culture is focused on the mission. The entire ART that is transparent and aligned will work to fulfill the ART’s vision and deliver the right solution.

- Built-in quality: Defects and failures impair the ability of the ART to reliably deliver on the solution and keep the ART’s vision. A vigilant attitude to maintaining quality by detecting and removing defects throughout development is necessary to keep the ART on track.

We now know the important qualities that are important for an ART. Let’s examine how to apply those values in terms of principles.

SAFe principles

The SAFe can be applied to different organizations in all kinds of industries. Differences between organizations and industries may be various and may make it difficult to move toward a generative culture. We may need a guide to align our practices so that the core values are developed and maintained.

10 SAFe principles are there to align practices to the core values. Let’s see how they can be applied to DevOps.

Taking an economic view

If in our SAFe House of Lean, we are looking at a goal of value, so we want to make sure we obtain that value growth incrementally and consistently. To do that, we need to make sure our decisions come from an economic context.

Donald Reinertsen identified an economic framework needed for incremental value delivery in his book, The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development. Major components adopted by SAFe include the following:

- Operating within Lean budgets and guardrails: Decisions should be made by those closest to the information, but boundaries regarding the decisions can be made at higher levels to ensure the necessary governance and oversight are still applied.

- Understanding economic trade-offs: As the ART needs to make decisions, it should be aware of the considerations that these decisions will have. These factors are development expense, lead time, product cost, value, and risk.

- Leveraging suppliers: Often, a decision may come to build versus buy. An organization may look to vendors for reasons such as insufficient capacity in its workforce, or that vendor may have a specialized skill set or be the only supplier of a specific component.

- Sequencing jobs for maximum benefit: ARTs cannot do everything at once. They need to prioritize what gives the maximum value soonest. Reinertsen recommends using Cost of Delay (CoD), the cost the organization incurs if it doesn’t deliver the value at the right time, over other measures such as Return on Investment (ROI) or executive decision, often lampooned as the Highest-Paid Person’s Opinion (HiPPO). SAFe takes this a step further by dividing the CoD by the size or duration of the job to give a bang-for-the-buck measure called Weighted Shortest Job First (WSJF).

Applying systems thinking

When we look at developing complex products encompassing systems of systems such as cyber-physical solutions, we need to employ a holistic view of the product. But that’s not the only system needing attention.

What’s often ignored is the system that is the organization. In 1967, Melvin Conway proposed the following idea, which is now known as Conway’s Law:

“An organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.”

In other words, the way an organization develops a product will be mirrored in the architecture of the finished product.

Because of the applicability of Conway’s Law, to optimize the final architecture, we need to look at a better way of developing the product. That allows us to look at and optimize our value stream.

Assuming variability and preserving options

We want to make sure we keep the spirit of accepting requirements anytime during development, as found in Principle 2 of the Agile Manifesto. A question then emerges: how can we keep the spirit of this principle intact?

We want to look at how requirements commonly change. Usually, at the beginning of development, there are a lot of unknowns. As development progresses, learning happens and the unknowns become knowns.

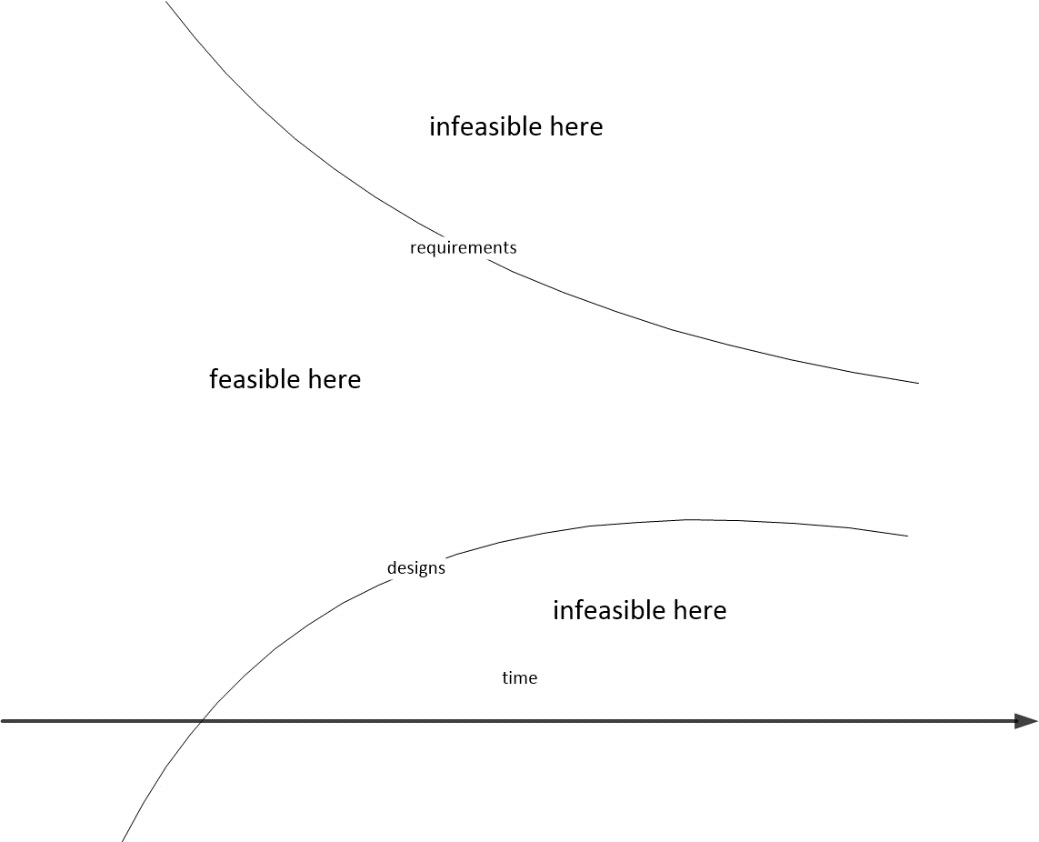

Learning also helps with identifying design options that will work with the requirements and those that won’t. The combinations of requirements, design options, and time result in a cone of uncertainty, as seen here:

Figure 2.3 – Cone of uncertainty

To navigate the cone of uncertainty, it’s best to keep requirements flexible and have several design options (commonly referred to as set-based design (SBD)) available in the early stages. As time progresses, the organization learns and finds which requirements don’t apply and which design options are infeasible.

Building incrementally with fast, integrated learning cycles

Incremental delivery is ultimately about learning. Producing an increment of value allows feedback from customers, which allows organizations to move on track to deliver more value. This incremental cycle of learning also allows the organization to find which of its design options are infeasible according to new discoveries in the environment.

Each team on an ART learns through its development cycles. To unify that learning, it needs to frequently integrate its work, test the integration, and seek feedback from the entire system. This integration should happen at least as frequently as its learning cycles.

Basing milestones on an objective evaluation of working systems

Many organizations that use the Waterfall method set up phase-gate milestones to ensure that everything is ready for the next phase and reduce risks. To move on to the next phase, the milestone is there to see whether the deliverables for that phase are ready and complete.

Phase-gate milestones do not handle risks because phase-gates will emphasize working as much as possible on a single-design approach. The rush to pass a milestone does not allow learning to happen to ensure that a solution is still within the cone of uncertainty. You may not realize that a solution is infeasible until it is too late.

SAFe looks at having periodic milestones. These milestones are based on the feedback and learning of each increment of value and of the integrated solution at that point in time.

Visualizing and limiting WIP, reducing batch sizes, and managing queue lengths

As we arrange the development using value streams, we want to make sure that flow occurs on the value stream to ensure continuous delivery of value. Ensuring flow relies on three key actions, as set out here:

- Visualizing and limiting Work in Progress/Process (WIP)

- Making sure we have small batch sizes

- Managing our queue lengths

We will examine these factors and look at achieving flow in more detail in Chapter 4, Leveraging Lean Flow to Keep the Work Moving.

Applying cadence – synchronizing with cross-domain planning

One of the SAFe core values we identified before was alignment. This value is important as we have multiple teams on our ART, and we want to make sure every member of every team is working in lockstep toward the ART’s vision.

To do this, teams on the ART apply both cadence and synchronization. Both are required to make sure that there is a balance between the inherent uncertainty in development and the current plan of the ART, allowing necessary pivots.

Cadence on the ART means that the teams have learning/development cycles of identical lengths. This constant length serves as a drumbeat of development. With a constant length, things can happen at a routine and predictable pace.

Synchronization on the ART means that the teams start and stop their learning/development cycles at the same time. This allows for the integration of the entire system to happen between teams.

The application of cadence and synchronization is illustrated in the following diagram:

Figure 2.4 – Cadence and synchronization with multiple teams

One final part of applying cadence and synchronization is cross-domain planning, which on an ART occurs at the beginning of every PI. There, all teams meet, along with the business stakeholders, shared services, architects, PM, and the Release Train Engineer (RTE) to align with the ART’s mission for the PI. Having this planning occur at a cadence allows all teams to inspect where reality deviates from what was originally planned and to adjust. This limits variability, which leads to rework and other waste, to a single learning cycle.

Unlocking the intrinsic motivation of knowledge workers

A generative culture welcomes the input and initiative of everyone in the organization. Empowered individuals working together toward a mission build that generative culture. But what does that empowered individual look like, and is a generative culture good for them?

Peter Drucker defines knowledge workers as “individuals who know more about the work that they perform than their bosses.” They are often the ones closest to the information of whether a solution will give value to a customer. These are just the kind of people our generative culture will need. How can we ensure they will stay and be actively engaged?

Daniel Pink, in his book Drive: The Surprising Truth of What Motivates Us, upended expectations when he found that monetary compensation worked, but only up to a certain point. After money, what really motivated people were these things:

- Autonomy: People want to have the freedom to explore the best solutions and self-direct the work they want to do

- Mastery: People want to improve their skills and build expertise

- Purpose: People want validation that the work they do has meaning

By being cognizant of the people in our organization and what really motivates them, we can ensure we build toward that generative culture.

Decentralizing decision-making

When optimizing lead time, organizations become cognizant of things that may cause delays. One of these sources of delay can be the escalation of problems and waiting for a decision.

With a generative culture with empowered individuals, it can be possible for most decisions to be made by the teams. Some decisions that are strategic in nature do have to be made at higher levels in the organization. SAFe recommends that these decisions to be escalated are like this:

- Infrequent: These decisions are not made often

- Long-lasting: The impact of the decision will last for a long time

- Incorporate significant economies of scale: The decision may affect the entire organization

Then come those decisions that are more of a tactical nature and that teams can make, and shouldn’t be constantly made by leadership, where the responsibility of leadership is making strategic decisions. In short, decentralized decisions are like this:

- Frequent: These are common decisions that must be made often

- Time-critical: These decisions have a high CoD

- Require local information: These decisions have information that is readily available to the team in the environment

Organizing around value

After going through the first nine SAFe principles, we want to set up the structure of our organization so that all the principles are reflected, allowing for the creation of a generative culture.

We’ve seen that we need to look at the economic factors when looking at delivering value. We’ve also seen that for our system, we must be cognizant of the communication links that mirror our architecture. We want to motivate our knowledge workers and allow them to make the necessary tactical decisions to accelerate value delivery.

The structure we want should mirror the development process while ensuring that handoffs occur with minimal delay. The structure also should work in small learning cycles and ensure a flow of value occurs.

In short, we want value streams instead of traditional hierarchical silos. In large organizations, there may be different departments organized to create stability. This stability is still necessary to handle large efficiencies of scale. How can this paradox still be maintained?

In SAFe, the value stream is seen as a network, getting the needed people and binding them together so that they work together to deliver value in the quickest way possible. The organization’s hierarchy is still there as a second operating system. The two structures, modeled after the dual operating system discussed in John Kotter’s book, Accelerate (XLR8): Building Strategic Agility for a Faster-Moving World, stand together as equals in the organization, each needed for different reasons.

We look at that network, the value stream, in the rest of this book. We will see how to identify and map our value stream, how to turn that into an ART, and then how to use a continuous delivery (CD) pipeline to assist the value stream. Let’s start by taking a close look at what a value stream is.

Value streams

We saw that SAFe principle #10 talked about organizing around value. To do that, our organization must set up and use value streams to make sure we consistently deliver value to the customer. But what precisely is a value stream?

The classic definition of a value stream comes from Lean thinking It describes the steps, the people that perform those steps, and the times associated with each step. It then becomes a platform for optimization so that an organization can reduce lead times.

SAFe takes this classic definition and applies it in two contexts. The first context is an operational value stream that describes the interaction the customer or end user has with the organization and which products are used in that interaction. The second context is a development value stream that describes the process of development of a product or solution.

We will first examine the classic definition and then move to how they have evolved into operational and development value streams.

Classic value streams

If we trace the origins of Lean thinking to manufacturing, a value stream was a set of assembly steps in a factory to produce a product that will leave the factory and be sold to a customer.

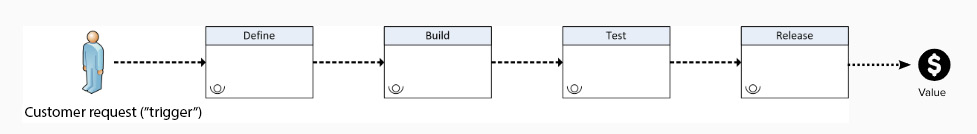

Applying value streams to product development, we change the start point to the initial request for a new feature or the initial idea for a new product. We then outline the major steps and who does them. The endpoint for the value stream is when that new feature or product is released to the customer. A representative example is shown here:

Figure 2.5 – Value stream

Value streams are a key part of the Lean methodology. James P. Womack and Daniel Jones identified a five-step process in their book, Lean Thinking, incorporating value streams. This process is summarized here:

- Work with the customer to identify value.

- Identify the value stream that details the activity from request to delivery.

- Ensure that flow occurs on the value stream created.

- When regular flow occurs, ensure customers can pull desired changes through the value stream.

- Continuously improve and optimize the value stream.

Operational and development value streams

The classic value streams introduced in the previous section certainly provide a model for a development process from initial concept to release to the customer. In SAFe, such a value stream is defined as a development value stream.

SAFe also looks at the ways customers use an organization’s products and services to achieve value. This view from the customer vantage point is defined as an operational value stream. The products and services touched upon in the operational value stream are developed and maintained by development value streams.

Let’s look at how operational value streams and development value streams work together to give the customer value with an example incorporating a fictional media streaming service.

The new customer wants to view programs on the streaming service. They will go onto the web portal (developed by the Portal ART) to set up an account, including any necessary billing. They may want to set up the streaming service on their smart TV using the mobile interface (developed by the Mobile ART). Finally, they may want to watch original programming exclusive to the streaming service (developed by the Content ART).

This customer scenario is shown here as an operational value stream with intersecting development value streams:

Figure 2.6 – Organizational value stream with development value streams

Value streams represent a key Lean practice. Adopting value streams and organizing work around value streams allows for an ART to create behaviors that affirm the Lean-Agile mindset, the core values, and the SAFe principles. As these behaviors settle in, the culture moves toward becoming generative, aligning everyone to the mission.

Summary

In this chapter, we started our examination of the Culture, Automation, Lean Flow, Measurement, and Recovery (CALMR) approach by looking at the first and most important factor: culture. We examined the work of Ron Westrum, which talked about three types of organizational cultures: pathological, bureaucratic, and generative. After looking at the characteristics of each of these cultures, we found that the one that really empowered our teams was a generative culture.

Once we settled on the ideal organizational culture, we then looked at how to move to that ideal culture. To help on this journey, we looked at the eight steps of the Change model created by John Kotter. We also saw these steps in action with examples from Ford Motor Company under Alan Mulally.

We identified the mindset that drives the behaviors we want to exhibit in our generative culture. The sources of this mindset come from both bodies of knowledge regarding Lean thinking the Agile Manifesto, and the SAFe core values. We also identified those principles from the Agile Manifesto that may need special attention when working with a team of teams or a scaled environment.

Also driving our behaviors and providing additional perspective are the 10 SAFe principles. We saw how these principles can act as guidance between core values, mindset, and practices.

Finally, because culture is built upon both structure and behavior, we took a close look at an ideal structure to create a generative culture. We further saw how value streams started out in Lean, and how SAFe evolves the classic definition of value streams to operational and development value streams.

In this chapter, we saw the importance of culture and ways to attain that culture through behavioral changes. Technology can help enable that change to a generative culture. In the next chapter, we’ll examine the technology that forms the automation aspect of CALMR, which performs that enablement.

Questions

Test your knowledge of the concepts in this chapter by answering these questions.

- In a generative culture, messengers are:

- blamed.

- trained.

- ignored.

- celebrated.

- What serves as the roof in the SAFe House of Lean?

- Time

- Value

- Leadership

- Innovation

- For teams on an ART to achieve alignment, they need to practice both cadence and ______.

- flow

- culture

- synchronization

- independence

- Identify two SAFe core values.

- Built-in quality

- Adaptation

- Empowerment

- Flow

- Transparency

- Value streams identify the _______, the people involved, and the time it takes to deliver something of value to the customer from the initial idea.

- tools

- culture

- steps

- products

- In the Kotter model for change, what comes after generating short-term wins?

- Celebrating and acknowledging the wins

- Empowering others to enact the vision

- Consolidating wins to drive more change

- Connecting the wins to the vision

Further reading

For more information, refer to the following resources:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1765804/—“A typology of organisational cultures” article by Ron Westrum, identifying the three types of organizational cultures, their characteristics, and their effects.

- Accelerate: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations by Nicole Forsgren PhD, Jez Humble, and Gene Kim—This is a research-based approach to the effectiveness of DevOps principles and practices.

- Leading Change by John Kotter—This is the book that describes the eight-step model to change an organizational culture.

- American Icon: Alan Mulally and the Fight to Save Ford Motor Company by Bryce G. Hoffman—A behind-the-scenes look at the changes Alan Mulally and others set in motion that saved Ford Motor Company.

- https://www.scaledagileframework.com/lean-agile-mindset/—An introduction to the Lean-Agile mindset in SAFe, featuring the SAFe House of Lean and the Agile Manifesto.

- The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development by Donald Reinertsen—This book is the basis for the 10 SAFe principles. An interesting read for introducing flow.

- Drive: The Surprising Truth of What Motivates Us by Daniel Pink—A glimpse into what motivates knowledge workers.

- Accelerate (XLR8): Building Strategic Agility for a Faster-Moving World by John Kotter—Another masterwork by Kotter on changing organizations by setting up the “Dual Operating System.”

- Lean Thinking by James P. Womack and Daniel Jones—An examination of Lean principles using value streams. The majority of this book is based upon an analysis of the TPS.