3. Savings on Steroids: Use a 401(k) and an IRA

If you are like a lot of people, when you hear the word saving, the image of some sort of miser shoots into your head. Maybe you envision a pale, humorless guy hunched over a table, painstakingly ticking off numbers on a detailed budget with a pointy pencil—or maybe a penny-pinching parent or relative admonishing you to give up something fun.

You might want to shout, “I’m young, leave me alone! Saving for retirement is for old people—I have plenty of time for that stuffy behavior later in life.”

As I have written about saving for retirement over the years, people with that miser image in mind have repeatedly said to me, “If I don’t enjoy my youth while I’m young, when will I?” That might explain why Aon Hewitt Consulting Services found that only 54 percent of people in their 20s use 401(k) retirement savings plans when they are offered at work.

But no matter what your age, I’m not urging you to deprive yourself. You might take a more modest vacation than you intend, but you can still take a vacation. You might keep a car longer than you’d prefer, but you will still get around. You might settle for a closet with plenty of shoes instead of one stuffed with them. Maybe you will watch a movie at home with friends instead of going out. You might brew your own coffee in the morning and fill up a mug for the road instead of dropping $3 each day at Starbucks.

If you are 22 and in your first job, all you need to do is come up with $20 a week and add more when you get raises; you should eventually build up $1 million. Make it just $15 a week throughout your working years, and you could still accumulate around $500,000. Or if you are 35 and saving for the first time, you can invest $50 a week and get close to $500,000. Add another $20 a week, and you should approach $700,000. Yet people often don’t try investing small amounts because they don’t understand the power they have over $10 or $20 a week. When the Employee Benefits Research Institute asked Americans of all ages and all income levels a few years ago whether they could afford to save $20 more a week, most said “Yes.” They just didn’t think it would do any good.

Of course, $20 does a tremendous amount of good. But you can turn nickels and dimes into hundreds of thousands of dollars only if you are smart about investing it. What’s unfortunate is that too often people get the hard part down (the act of saving, or yanking money from their pocket and setting it aside for another day). Then, they get the easy part wrong (the act of sticking their small savings in the right place so that investing transforms a pittance into thousands). This is a shame—and absolutely unnecessary.

You have a couple simple strategies available to you. And if you have an elementary school education, you can master them with little effort. I’m talking about two tools that work almost like alchemy, turning pocket change into a pot of gold over time. One is an IRA, a savings account designed specifically for growing money into a retirement nest egg. (You usually have to set up an IRA away from where you work.) The other might be right under your nose where you work. It might be called a 401(k), a 403(b), a 457, or some other equally uninviting name. (They get their names from tax laws.) All are retirement savings plans, and I explain step by step how to handle them a little later.

First, I want to get past the off-putting names, or perhaps the incessant nagging from someone who has made you want to ignore them. These tools might sound as unfriendly as the miser. But they are powerful money-making machines. Choosing whether to use them is like choosing between driving a car and walking to a destination that’s 10 miles away. You might well be able to walk 10 miles, but you’d be silly to try to do it if you are in a hurry to make an appointment in half an hour. If you drive a car instead, the trip takes a few minutes.

Likewise, you can build up retirement savings either the hard way, through devices such as savings accounts at banks, or the easy way, through IRAs and 401(k) plans. Too many people make life hard on themselves because they don’t choose the easy investing way.

The Hard Way

If you don’t use a 401(k) or an IRA, it’s like walking a long distance, and you might never get to your destination because it will take extraordinary, laborious, unfulfilling effort. You will have to deprive yourself either during your savings years or after you retire. But if you use the two simple tools I’m advocating, it will be the opposite. You will feel the difference very quickly between the futile efforts you’ve been making and the smarter approach.

It will be like driving a car. You will speed toward your destination with very little effort if you start early enough. You won’t have to live like a pauper while saving or during retirement.

Here’s an example: Let’s say you are 35 years old. You have been pulling hard-earned cash out of your paycheck for the past 15 years and diligently saving it in the bank. You have $30,000 and 32 years to go before you retire. When that day comes, you know you will need at least $500,000 to keep up your modest lifestyle. But times have turned rough, and you aren’t in a position to save additional money for retirement. The key for you will be to let your existing $30,000 grow effectively.

If you leave that money in a savings account in a bank, what will you have on the day you retire at age 67? Maybe about $46,000— not enough to get you through more than a handful of retirement years.

Now let’s look at that same original $30,000 one more time. This time, let’s assume that you’ve been smart. Instead of using a savings account, you have put it all either in your 401(k) or 403(b) savings plan at work or in an IRA, and, invested the money wisely in a mutual fund that contains stocks and bonds. And let’s say that you earn an average of 8 percent a year for the next 32 years.

By using either the 401(k) plan at work or an IRA away from work, your $30,000 should become about $385,000 by the time you retire when 67—not the puny $46,000 that would have resulted in a savings account.

So, you see, amassing money doesn’t have to be about deprivation. It has to do with being smart about where you stick the money.

What’s the Difference?

Why is there such a dramatic difference in what $30,000 can become in a 401(k) or IRA versus a savings account?

Let’s start with the 401(k) because it gives you three huge advantages over a savings account: stock market investments, enormous tax savings, and potentially thousands of dollars in free money from your employer.

When you have a savings accounts at a bank, you will never make much money. You might earn about 2 percent a year, if you are lucky. But in 401(k) plans, people can invest in mutual funds that select stocks and bonds. I explain these in Chapter 7, “What’s a Mutual Fund?.” For now, I just want you to know that, historically, money in the stock market has grown 9.8 percent a year, on average. If you blend stocks with bonds in what’s known as a balanced fund, the average gain over many years has been about 8 percent, according to Morningstar’s Ibbotson division. That’s not a specific guarantee for the future, but if history repeats and you are using good mutual funds in your 401(k), you could make 8 percent a year, on average, instead of the 2 percent in your bank account. That’s a tremendous difference over many years of investing.

That’s not all. Employers often give you free money when you participate in the 401(k) plans they offer you at work. They give you what’s called “a match” or “matching money.” For you, it’s like getting a raise every year— maybe $1,000 or more simply as a reward for participating in the company 401(k). What could be better? It’s free money, and it’s a reward for doing what’s already good for your future.

Employers don’t do this out of the kindness of their hearts. They need a lot of participants in their 401(k) plans so that they can handle all the paperwork and administrative tasks economically. They also provide matching money because, under federal rules, they have to get people of all income levels to be involved in their retirement savings plans. If lower-income people shrug off the 401(k), employers have to cut back on the benefits they give management. Of course, employers don’t want to do this because they won’t be able to recruit sharp people. Talented managers are well aware of the value of a 401(k) plan, and they want to get everything they possibly can from it.

But don’t think of the company match as some kind of plot with weird strings attached. You aren’t being unfairly manipulated. What you see your employer offering is real and good. Don’t be like half of workers 20 to 29 who ignore the 401(k) they are offered. Take a lesson from the savvy managers at your firm. They are using their 401(k) benefits to the hilt, and you should, too.

Get the Match

Getting free money from your employer is a great deal that you’d be crazy to pass up. Imagine if your boss came to you and said, “We’d like to give you another $1,000 a year for working with us, and you don’t have to work one extra hour or take on any more responsibility to get it.” Would you even consider telling the boss you weren’t interested in the money? I doubt it.

Say you make $50,000 a year at your job, and you can qualify for $1,500 that year in matching money under your plan (3 percent of your pay). If you were 35, did what you needed to qualify for the full match each year, received 3 percent raises a year, and earned an 8 percent return on your money in your 401(k), you would end up with about $237,300 at retirement simply from the free matching money alone—not from any money you personally set aside from a paycheck. Now, that’s a deal!

That should be a huge motivator, a sure thing. It’s certainly better than betting on the lottery. Still, according to a survey by the Consumer Federation of America, 21 percent of Americans think the “most practical” way to accumulate a few thousand dollars is to win the lottery. Only 26 percent think they can save $200,000.

You did it simply with your employer match. And with your own money plus the free matches, you ended up with a grand total of $712,000—an even better deal!

The Power of Warding Off Taxes

Perhaps the top advantage of them all is that a 401(k) keeps the tax man away from your money year in and year out. You don’t pay taxes on the money you put into a 401(k), and you don’t pay taxes on the money that builds up in your 401(k) account over the years. Eventually, you pay taxes after you retire and start spending the money you saved. But the impact of delaying taxes is tremendous. I’m not talking chump change—it’s potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Avoiding taxes legally is one of the smartest tactics at your disposal to spin tiny savings into gold. Every wealthy person with a financial adviser uses this trick to the fullest. This is how they turn a small fortune into a cushy lifestyle, luxury vacations, and trust funds for their kids. But you don’t need an adviser to make your way through the same terrain.

One of the common man’s most delicious tax breaks is served to employees at work each day on a platter. It comes through the company 401(k) plan. When you see a 401(k) plan, it is like posting a “Keep Off” sign on your money to ward off the IRS. And it should beckon you—it says to you, “Put your money here, and Uncle Sam won’t touch it.” Years can go by, and your original $30,000 can become $50,000. And Uncle Sam won’t make you share any of that $20,000 gain with the government. More years can go by, and your original $30,000 can become $500,000. And Uncle Sam still keeps his hands off.

In fact, the way it’s possible to amass that $500,000 is by holding Uncle Sam at bay. If each year he was showing up at your doorstep and making you share some of the money you had gained with him, you would end up with nowhere near half a million dollars.

If you put all your money into a savings account, none of it is protected from taxes. Uncle Sam shows up every year at tax time and says, “Give me some of that interest money you have made.” You have no choice but to pay because you put the money where it’s open season for the government.

Let me show you the contrast in real dollars. Let’s go back to that original $30,000 sitting in a savings account in the bank. Look at what taxes do to it if you are in the 25 percent tax bracket. Remember that, if you kept that money in a savings account until you were 67, you would have roughly $46,000. If you had been able to keep the IRS at bay, it would have been better—still nothing to rave about, but better. Instead of $46,000, you would have had about $57,000 when you retired.

So let’s leave the bank savings account and look at another equally vulnerable approach to saving.

Mutual Funds Get Taxed

Let’s assume that you jumped ahead in this book and learned that mutual funds can do a lot more for your future than a savings account. But let’s say that you skipped this chapter about the tax advantages of a 401(k) plan. So you ignore the 401(k) plan at work and also an IRA. You go straight to a mutual fund company and plunk your $30,000 into a solid fund that invests in stocks, and you don’t protect it from taxes.

Year after year, you earn good money in that mutual fund—let’s say the same 8 percent annually you would have made in your 401(k). But outside your 401(k) or IRA, there is a dramatic difference. Uncle Sam shows up every year for his take and makes you fork over part of the money you made on your mutual funds. The result: On retirement day, you have roughly $171,000, not the $385,000 you would have had if you had simply invested the same $30,000 in your 401(k) plan at work. (I assumed a 25 percent federal tax rate and took a couple liberties with this example.) With an actual 401(k), you would not have been able to invest $30,000 in a single year, but rather could have done it over two years. But I wanted you to see the comparison with the earlier savings account example in which a person invested $30,000 and ended up with only $46,000 at retirement. Meanwhile, if you want to see the impact of your tax rate on savings, try the calculator I used: “How will taxes and inflation affect my savings,” at http://calculators.aol.com/tools/aol/savings06/tool.fcs.

So amassing money isn’t just about digging deeper into your pocket and depriving yourself so much that you feel like a pauper. It’s simply about being smart about where you put the money. It’s knowing one simple fact: If you aren’t paying taxes on your savings year in and year out, the money can grow vigorously. It’s like putting your money on steroids. It’s the only way to turn $20 a week into a sum close to $1 million. And Uncle Sam wants you to do it so that some day you aren’t a destitute old person and a burden on society.

Of course, when you are retired, you will have to pay some taxes on money you remove from your 401(k) for living expenses. By that time, if you have invested well in the ways I describe in this book, you will have amassed a tidy sum and will be able to afford to pay the tax. Also, because you won’t be working then, the tax rate you pay might be smaller than what you pay now.

An IRA Instead?

But what if you don’t have a 401(k) at work? Only about half of Americans do. You still have another option that is just as good at keeping the IRS at bay so that you can turn meager savings into a retirement treasure chest.

It’s an IRA, an individual retirement account. Using one takes a slightly greater effort than using a 401(k) because you usually can’t take care of the paperwork right at work. But it’s not difficult to do, as you see in Chapter 5, “IRA Decisions: How to Start and Where to Go.”

For now I just want you to understand that if you had that very same $30,000 in an IRA and used the very same mutual funds as in a 401(k), the result would be identical after 32 years: At retirement, you would have about $385,000 because Uncle Sam would have had a hands-off policy for your money during the full 32 years you needed to grow it.

Why not just use an IRA and skip a 401(k)? Nothing is wrong with that approach from a tax perspective. But for three reasons, you shouldn’t turn your back on your 401(k) at work: The first two I have already provided. If you don’t use your 401(k), you essentially tell your employer that you don’t want the free money offered to you, and that’s just plain stupid. Also, your 401(k) is easy and convenient; it’s at your fingertips every day you go to work. Ten minutes spent filling out the paperwork sets the groundwork for making thousands—maybe hundreds of thousands—of dollars.

But there are limits to how much money you are allowed to stash away for retirement without Uncle Sam raiding your account. Based on federal rules, a typical 401(k) lets you put away up to $17,000 a year ($22,500 if you are 50 or older). But you can put only $5,000 into an IRA (or $6,000 if you are 50 or older).

More about those limits later, but now I want you to understand that, in the best of all worlds, you would not choose between a 401(k) and an IRA. You would use both—your 401(k), if you have one, and an IRA. This is especially important if you are approaching retirement and have saved very little. In that case, stashing away just $5,000—or even $6,000—a year probably won’t be enough. By putting as much money as possible in both your 401(k) and an IRA, you can make up for some of the lost years. And Uncle Sam will help you by keeping his hands off while you save.

How to Use Your 401(k) or 403(b)

Before we start, make sure you are really using a 401(k), a 403(b), or a similar retirement savings plan offered by your employer. That probably sounds like a ridiculous statement, but it’s not.

A few years ago, benefits consultant Hewitt Associates surveyed employees at large companies about their 401(k) plans. What the researchers found was disturbing: A full 29 percent of people who weren’t participating in their company 401(k) plans thought they were.

Somehow someone got some wires crossed—maybe because many employees find 401(k) plans so confusing, and maybe because employers often fail to give their staff understandable information. Regardless, for these workers, a disaster was in the making.

If these people thought they were building retirement money for their futures, they would face a rude awakening on retirement day. They were on their way to having nothing because they weren’t putting a penny into the 401(k) plan, and their employer wasn’t doing it, either.

Don’t assume that you are participating in your 401(k) plan at work simply because you have heard that your company offers the plan. To participate, you usually must take action. In many companies, you have to notify your employer that you want to participate. You do this by signing a form or saying “Yes” on your company’s intranet site. The company likely calls this “enrolling.” When you do it, you are telling your employer to remove some money from your paycheck each payday and to keep the money for you in the 401(k) plan.

Notice that I said you usually have to take action by enrolling in your 401(k). Since a new law passed recently, many companies are beginning to sign up employees for the 401(k) plan without asking for their permission. This is called automatic enrollment, and if your employer does it, the approach is good. The idea is to get more people to take part in this critical preparation for retirement instead of waiting while people procrastinate.

Just make sure that either you or your employer has signed you up. Don’t guess. You don’t want to miss out on this.

After you have enrolled in your 401(k), every time you get a paycheck, a little money will be removed—as much or as little as you want. But don’t feel trapped on this. Even if your employer automatically removes money from your paycheck and deposits it in your 401(k) account without asking for your permission, you are the boss. You can change your mind at any time about the amount. You can even stop contributing anything, if you want, and you can increase what you save. You can make changes constantly.

Changing Your Mind

If you tell your employer to remove $20 from each paycheck, that’s what your employer will do. On each payday, instead of putting the $20 into your paycheck, your employer will put it into a 401(k) account with your name on it—like a bank account, only with all the advantages I just described.

A month later, if you decide that $20 is too much, but you think you can afford to give up $10 from your paycheck, you tell your employer to drop your old request and start putting $10 into your 401(k) account on payday. It’s simple to do. You contact the person or office at your company that handles benefits such as health insurance and either fill out a form or visit the Internet site provided by your employer. It takes less than a minute to do.

If you put aside $10 for several months and you are able to pay your bills and have some fun, you might decide that you can afford to put more into the 401(k). Then you just tell your employer that you want to make a change. You could raise the amount to $15 per paycheck if you wanted and go higher over time—especially when you get raises.

Whatever feels comfortable to you is fine. Making changes is perfectly acceptable—your employer expects them. At many jobs, you can change the size of your contributions every day, if you want, although they won’t show up until the next paycheck.

If you suddenly get strapped for cash and decide that you need every penny from your paycheck, you can go back to your employer’s benefits office and say that you want to stop contributing to the 401(k) plan for a while. Even if you want some more fun money for a few months, you can go back to your employer and stop contributing. No one will ask you why you made a change; they simply do what you request.

Meanwhile, any money that you already contributed stays in an account with your name on it. Your employer acts just like a bank and holds on to the money for you for as long as you want.

As months and years pass, the money in your account keeps earning interest, or what is called a return. As the years go by, your return makes the pot of cash grow larger. When you retire and no longer get a paycheck from a job, you pay yourself out of that pot of money you were kind enough to provide for your own future.

Getting Started

To get started for the first time in your company’s 401(k), you simply need to call or visit the person or office at work that handles benefits. If you don’t know where to go, think about the last time you received information on health insurance. It probably originated at the same place that handles the 401(k), or at least someone in that office can point you to the right person. You can also ask your boss or coworkers. It’s not a dumb question.

When you contact the benefits staff, say that you want to start contributing to the 401(k) plan. You’ll get a short form to fill out or learn where to find it online. On that form, you state the percentage of your salary that you want to put away for retirement each time you get a paycheck.

You don’t have to figure out a dollar amount. All you need to state is the percentage of your income you will put aside. Some people just pick an amount that feels comfortable—somewhere between 1 percent and 15 percent, or maybe even more. But if you want to know what a percentage will mean to you in the dollars you will take home with each paycheck, an Internet calculator can give you the full picture in a few minutes.

Large employers often offer you dandy calculators over the Internet to figure out what to do with 401(k) plans. If yours doesn’t, simply go to www.paycheckcity.com and use the 401(k) Planner calculator or see “How Do 401(k) Salary Deductions Affect My Take-Home Pay?” at http://calculators.aol.com/tools/aol/paycheck01/tool.fcs. You can play with different percentages to see what feels right to you.

For example, if you are making $35,000 a year and you get paid every two weeks, the calculator shows that if you have your employer put 5 percent of your pay into the 401(k) plan, your take-home pay will be reduced $59.50 every time you get a paycheck. That means each week you will have only $29.75 less to spend than you normally would. And if you are in your early 20s and keep it up, that small weekly sacrifice could eventually turn into $1 million—and almost certainly will become that if you add part of each raise in the future.

While you are at the calculator, give yourself a chance to see what would happen if you devote just a little more of your pay to the future. Redo the calculation to show what 10 percent would do to your take-home pay. In the example of making $35,000 a year, giving up 10 percent would mean $119 less in spending money every two weeks. That’s $59.50 a week. But the larger amount greatly increases the chances of building up a comfortable nest egg, especially for a person who never saved anything during his or her 20s.

A rule of thumb states that if you put 10 percent of your pay into a retirement account, starting with your first job, you will have what you need later in life. Some financial planners feel more comfortable with 15 percent because healthcare costs are growing so much and could drain savings fast for a retiree.

There are limits, however. If you have a 401(k) in 2012, you can put as much as $17,000 into it for the year and get the full tax benefits. If you are 50 or older, you can add another $5,500, for a total of $22,500.

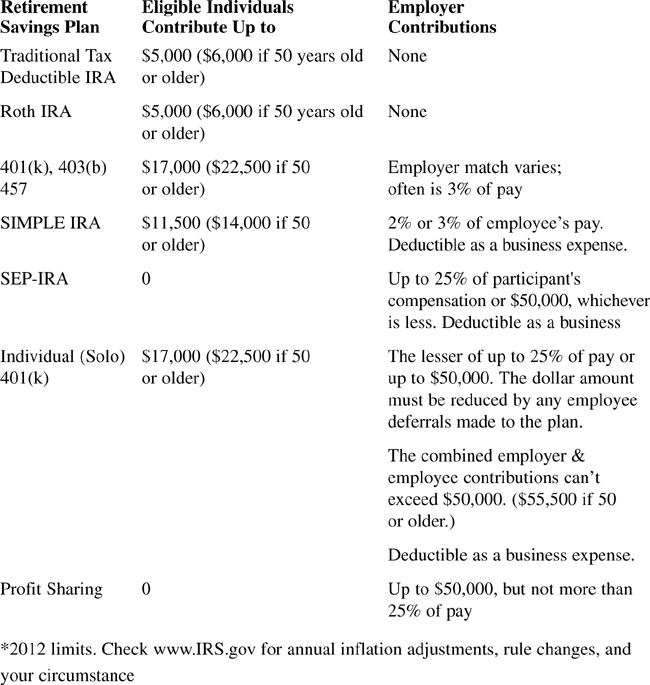

The limits change from year to year based on inflation and tax policies. So look for alterations in 401(k) and IRA limits each year and adjust your contributions to the times. Table 3.1 provides the limits for 2012.

Table 3.1. Annual Limits for Retirement Accounts

More Tax Help Than You Imagined

If you did the take-home pay calculation I suggested in the preceding section, you might be a little perplexed at this point.

You might see that when you contribute 5 percent of $35,000 to your 401(k), you give up $59.50 in take-home pay. But you are actually putting $72.92 into the plan for your retirement.

How can that be? You might assume that your reduction in take-home pay would be exactly the same number as your contribution to the 401(k) plan. But you have just uncovered one of the truly delightful parts of using a 401(k) plan. I told you previously that Uncle Sam doesn’t touch the money you make within the plan. But it gets even better than that.

The government is so worried that you won’t save enough for retirement that it gives you a tax break right up front every time you put a penny into the 401(k) plan. This, too, should come as delicious news for you, especially if you are worried that your 401(k) contributions will immediately slash your ability to pay your bills. What it means is this: You aren’t really sacrificing nearly as much today to save for your future. Because Uncle Sam immediately cuts your taxes on anything you put into your 401(k), you are still keeping more take-home pay than you would have imagined.

If you earn $35,000, the government reduces taxes on your paycheck by $13.42 cents. If you contribute the same $72.92 to your 401(k) on every payday, you will save $13.42 on taxes each time. For the year, that’s about $348 in tax savings—not bad at all. It makes saving for retirement cheaper than you think.

Here’s a quick way to envision your tax savings: If you are in the 25 percent tax bracket, every $1,000 you put into your 401(k) cuts your federal taxes by $250 that year. So you aren’t really doing without $1,000 of your pay. You are simply doing without $750 because Uncle Sam is letting you keep a larger chunk of the money you have earned.

So when you use your 401(k), it’s like buying a better future for yourself by using a 25 percent discount. You aren’t stashing away your money at full price. Instead, it’s as though you are making use of a 25 percent off coupon. That lets you acquire a better future without living like a pauper.

Take Baby Steps

Increasingly, employers are not asking their employees whether they want to participate in the 401(k) plan at work. Instead, these employers automatically put employees into it. As I said previously, don’t assume that you are in or out of your company’s 401(k) plan without asking your benefits office.

Yet if your company has an “automatic plan,” your employer might be removing 3 percent of your pay—or some other amount—and putting it into an account for you every time you get a paycheck.

If that is the case, you are fortunate. You are taking a step in the right direction. Don’t simply turn your back on your 401(k) and consider the deed done, however. You still must think about what you will need for retirement, and 3 percent of your pay isn’t going to do it for you.

Consider moving your contribution up to 5 percent or 10 percent of your pay. If you have never saved for retirement and are in your 30s, 40s, or 50s, this is especially critical. Go to your benefits staff, request a form, and simply change the percentage of pay they will take from each paycheck. If you want to know what this will do to your paycheck, try the calculators I mentioned: See www.paycheckcity.com and use the 401(k) Planner calculator, or go to “How Do 401(k) Salary Deductions Affect My Take-Home Pay?” at http://calculators.aol.com/tools/aol/paycheck01/tool.fcs. If you don’t have a computer, you can use one free in a public library.

If you don’t think you can afford to put 5 or 10 percent of your pay into the 401(k), experiment with a lesser amount—knowing that you can increase it later. If you can’t decide what you can spare from your paycheck, don’t wait to figure it out. Indecision is your enemy. You could lose valuable months and years procrastinating.

Jump in now, and promise yourself to think about it again later. Write it on the calendar so that you actually do it.

Can You Spare a Dime?

If you are terrified about getting by if you save some money in the 401(k), start with a low number—even 1 percent. If you want to prove to yourself that you can survive without a little money, try an exercise: Every day, empty spare change from your pockets or purse and put it in a jar next to the sink. At the end of the week, add up the amount. That’s the money you lived without during the week. Did you survive without it?

You probably did just fine. So make use of that revelation. Go to your benefits office immediately and start having your employer remove that amount from your paycheck. I have been suggesting this to people for years in my columns and have asked people to let me know if saving that amount of money each week was ever too much. I have never heard anyone say it was impossible to get by, and a lot of people have said it was just the assurance they needed to get started.

If you start out in your 401(k) with a very small contribution, ask yourself in a few weeks how you are doing. Are you paying your bills and putting food on the table? Are you still having a little fun in life? Put a date on a calendar so that you don’t forget to ask the questions. If you are doing just fine, go back to your benefits office and increase the amount—maybe go to 5 percent. Don’t wait, because days will turn into months, and months into the lost power of compounding—thousands of dollars.

If you are already at 5 percent, go to 7 percent. Also promise yourself that when you get a raise, you will put half of it into the 401(k) plan. Don’t wait for the first paycheck reflecting the raise. Get a 401(k) form as soon as you hear that the raise is coming, and increase the percent so that you deploy some of your raise to your retirement future from day 1.

That’s often the most painless way of increasing retirement savings because people don’t miss money they never were used to having.

Finding Cash

Over the years, numerous people have contacted me to tell me where they found money to save—painless ways that don’t require them to live like a pauper or cut out the things they love.

Here are some of their suggestions:

• Dump one cell phone in a two-cell-phone family. Save about $480.

• Dump caller ID on the land-line phone into your home. Save about $90.

• Use calling cards instead of a long-distance carrier. Save about $100.

• Get rid of the second phone line into your house. Save about $275.

• Shop for groceries with coupons, or shop at a cheaper store. Save about $780.

• Carry higher deductibles on home and auto insurance. Save $300.

• Eliminate one coffee-shop coffee or one alcoholic beverage a day. Save $730.

• Stop smoking. Save about $1,450.

• Cut out two restaurant meals a month. Save about $350.

• Use the library instead of buying books. Save $180.

• Cancel cable TV. Save $600.

• Order prescriptions through the mail. Your insurance company likely charges a lower copayment than a drug store.

Also beware of missing credit card payments. Often you are hit with a $29 charge, and your interest rate can rise if your payments are late. In addition, be aware of the money you waste when you carry a credit card balance from month to month. The money you are paying in interest could have gone toward savings. To get rid of credit card debt, pay some amount above the minimum, and get techniques from reading Liz Pulliam Weston’s book Deal with Your Debt (Prentice Hall, 2005).

If you have raised children and they are now on their own, you might find additional savings simply by cutting back life insurance. For more saving ideas, see financial planner Sue Stevens’ list “101 Ways to Cut Expenses,” at www.morningstar.com.

Then try to look for small savings in your own lifestyle. For the next two weeks, carry a pocket notebook. Every time you buy something—whether it’s a treat from the candy machine, a magazine, or whatever—mark down the item and price.

At the end of two weeks, look over the list and put a check mark by the items you wouldn’t really have missed. Tally it up. The dollar amount is what you could save. Let’s say it’s just $5 a week. If you invested that amount week after week for about 40 years and earned a 10 percent return, you’d have more than $138,000. Try it yourself with the Quick Savings Calculator in the personal finance section of the Money CNN Web site: http://cgi.money.cnn.com/tools.

Qualifying for the Match

Although I told you to start out by contributing only 1 percent, if that is the only way you can feel comfortable, there is a better way if you can swing it. Put enough of your own paycheck into the 401(k) each payday to qualify for every penny of matching money your employer provides.

It’s impossible for me to tell you how much you need to put aside to get all the free money your employer is willing to give you. That’s because different companies use different formulas. You can ask your benefits office what you must do to qualify for the maximum matching money your employer provides.

Look at why it matters. Assume that you are 25 and are making $35,000. You get a very common match from your employer: 50 cents on every dollar you contribute, up to 6 percent of your salary. So at age 25, you decide to put in the full 6 percent of your salary, or $2,100. And your employer provides the full match, $1,050.

Every year for the next 40 years, you contribute 6 percent of your salary so that you get the largest match possible from your employer. The result: With that matching money, your contributions, and an 8 percent return annually in your 401(k), you’ll have about $1.2 million when you retire. And your employer’s matching money was not chump change in the outcome. If your employer hadn’t been giving you any match and you had been socking away the same 6 percent year after year, you would have had only about $809,000 at retirement.

As you decide what to put into your 401(k) plan, know what you must do to get the maximum matching money from your employer. If you contemplate passing up some of that money, picture your boss standing in front of you with outstretched hands brimming with $400,000 in cash. He says to you, “I’d like you to have this.” As a $1,000 bill falls from the pile and floats to the ground, do you say, “That’s very nice of you, sir, but I think I’ll pass”?

Instead, try calculating the impact of your employer’s match using the 401(k) Calculator at www.bloomberg.com/personal-finance/calculators/401k/. Incidentally, besides a starting salary of $35,000, I figured in raises of 3 percent a year for each of the 25-year-old’s 40 years of work.

Procrastination—Not Money—Hurts

So now you have a decision to make: Just how much money will you put into your 401(k)? Don’t back-burner that decision—if you do, all the research into 401(k) behavior shows that you will put off the decision for months and maybe years. You will get busy working at your job, carrying out the garbage, or driving the kids to music lessons and soccer games, and you’ll forget about it. Instead, go to your benefits office right now while you are thinking about it; if you start with a small contribution, mark on a calendar when you will make yourself consider increasing your 401(k) contribution.

Don’t think of this as a sacrifice, or you might not get started. Instead, look at it as helping yourself. You are making an investment in your future, not depriving yourself. Think of the kindness you are showing yourself by starting now. Consider that a 20-year-old can become a millionaire by retirement simply by investing about $20 a week. Yet a 35-year-old who wants to be a millionaire, and has done nothing about it, has to give up a lot more per paycheck to get there—about $87 a week. For a 50-year-old, it’s about $450 a week.

So no matter what your age, move into action now. Tell yourself that if you get into gear now, you will remove the chance that you will deprive yourself later.

If you are like 36 percent of people who don’t participate in their 401(k) plans, you might be saying to yourself, “I just can’t spare a dime.” But the evidence shows that you can. Hewitt Associates studied thousands of 401(k) plans and found that inertia, not money, seems to be the biggest deterrent to saving.

The consultants looked at what people do when they have to sign up for 401(k) plans and how that differs from the few companies that don’t require people to sign up. In about 10 percent of companies, people aren’t required to sign up for the 401(k). Their employer simply enrolls them automatically and starts removing a little money from their paycheck.

Now, here’s the interesting part. In companies that put people into the plan automatically, workers have to go to the benefits office and fill out a form if they don’t want to be in the 401(k) plan. In other words, it’s the opposite process of the usual. The action step is to fill out a form saying “No” rather than filling out a form saying “Yes.” In that case, guess what happens?

Very few people bother to say “No.” Hewitt found that only about 10 percent of people decide to opt out of the 401(k) plan when their employer put them into it automatically. So somehow they get by financially with a tiny contribution coming out of their paycheck each month for retirement.

What’s the explanation for this huge discrepancy? Why do only 10 percent say they can’t put money away for retirement versus the 36 percent who don’t when it’s up to them to make a decision? Hewitt’s answer: procrastination, not money, is why most people skip the 401(k).

Most of us can give up a little of what we have earned to provide for our future. In fact, Fidelity investments has calculated that a 25-year-old who earns $35,000 and gets a 1.5 percent raise over the cost of inflation each year will make $1.9 million over a lifetime.

So don’t let valuable years go by for you. If your employer doesn’t enroll you automatically in the 401(k) plan, go fill out your form now.

And if you think you are already using your 401(k) plan, ask the benefits staff to confirm it. Ask for a statement that shows how much money you are putting into the plan and where it’s going. You might get overloaded with material at this point. You will probably see a befuddling mix of gobbledygook. But don’t worry about that now. By the time you finish reading the chapters on mutual funds and investing, this stuff will never be vexing to you again. You will look at today’s mess of 401(k) choices with the same familiarity you look at the list of flour, salt, and sugar in a recipe.

For now, I just want to encourage you to start putting money into the 401(k) if you haven’t already done so.

Leaving Your Job

If you change jobs, all the 401(k) money you accumulated at your old job continues to belong to you. You have some options: You can either take the money with you or leave it in the 401(k) plan at your old job.

If you take it with you, do not spend it, because you will pay dearly for that mistake. Uncle Sam will show up and charge you a 10 percent penalty, plus taxes. In addition, you will cut off your future by losing the power of compounding to make your money grow huge.

If you leave your job, do one of three things: Leave your money in your old 401(k), ask your employer to transfer it to the 401(k) at your new job, or open an IRA (as I describe in Chapter 5) and have your old employer transfer your old 401(k) money directly into the IRA.

Make sure you follow the rules, using an official transfer, or “rollover.” Only that will insulate you from getting slapped with a shocking tax bill.

Leaving your money in your old 401(k) is the easiest approach. If you don’t like your investment choices there, moving it to an IRA will give you all the choices you could want. Uncle Sam will continue to keep his hands off your money so it can grow.

Emergency Bailout

If you have a 401(k) and run into an emergency—or just need cash—you can borrow money from yourself in your 401(k). I want you to know this because it should enhance your level of comfort, knowing that if you are in financial trouble, you have options.

But I also want to tell you not to raid your 401(k) if you can possibly help it. If you do, there are stringent rules. You generally can borrow money at any time, but you also must repay the money with interest within five years, or Uncle Sam will tax you hard—not just the taxes you’d normally owe, but a penalty, too.

Meanwhile, borrowing works in reverse on the power of compounding. You could slash thousands of dollars from your future. So, resist friends who tell you that your 401(k) is an easy source of cash for something you want rather than need. If they are dipping into their 401(k) plans, they are undermining all the hard years of saving they have put into it.

If you have a home and want to borrow for a home improvement, a home equity loan is usually a smarter approach. If you are sending children to college, dipping into your 401(k) could reduce financial aid grants, or free money offered by colleges.

Students and parents can borrow money for college through federal loans available in college financial aid offices. These are better options than robbing your future by tapping a 401(k). Remember, after graduation your child has a lifetime to pay off college loans, but the time is drawing near for your retirement. And if you run short of money in your 70s because you drained your 401(k) to pay for your child’s college, no bank will give you a loan to buy groceries and medicine.