10. The Only Way That Works: Asset Allocation

Stay calm.

I threw a lot of information at you in the preceding chapter, and you might be in the mood now to toss it aside and simply try to pick the one right mutual fund.

Please don’t.

You will certainly find plenty of temptation in the marketplace. Potential investors are bombarded with ads beckoning to them to trust a winner, and TV shows, publications, and Web sites make stars out of a handful of investing pros. So when faced with more than 8,000 different fund choices for an IRA or a dozen in a 401(k), busy people often want to find a shortcut. They spot a fund manager being lauded in the news media and think their problems are solved: They will hand over their money to that one remarkable genius and be done with it; they’ll trust someone who clearly knows his or her way around the stock market or bond market.

Usually, they end up disappointed, face to face with the unpleasant truth in investing: No single magic fund or investment savior will always grow your money, keep you out of harm’s way, and outsmart the other pros who are trying to be outstanding.

In fact, college finance professors have studied at length whether stars truly exist in the investment world, and the academic research is discouraging. It comes down to this: Fund managers shine for a while, bask in public attention, and attract a lot of headlines and millions of dollars in new money to manage as investors glom onto a winner. Then, often after only a year, the fund ends up fairly mediocre, or even worse.

There’s actually a joke about this among investment professionals. It revolves around a coveted award that is handed out every year to an exceptional mutual fund manager. The award comes from a firm named Morningstar, which is well respected for analyzing mutual funds. At the end of each year, Morningstar anoints someone “The Manager of the Year,” the equivalent of the Academy Award in the fund business.

If a fund manager is named “Manager of the Year,” it’s a tremendous tribute. Firms that receive the honor make a fortune on new money coming through the door as investors seek the Midas touch. But the joke among fund managers is that it’s a dubious honor: Often the “Manager of the Year” falls from stardom the next year. A few have held on or returned to stardom a few years later, but more often than not, all the excitement ends in mediocrity.

Academic studies come to this bitter conclusion: Winners only appear to be winners for a while, but they rarely keep it up. Luck, or being in the right place at the right time during a cycle in the stock market, seems to be why fund managers stand out temporarily. That’s very different from possessing unusual investing prowess that lasts. One or two years of amazing returns simply create an illusion of outstanding skill.

Why Star Funds Fade

When you think about it, an apparently great fund can fizzle into a so-so fund for good reason. If a fund manager has only a little money to handle, investing it is a lot easier than when he or she has millions or billions to deploy. If you doubt this, think about what it’s like to make a meal for a couple friends, compared to 100, or consider how well you handle one project at work versus many dumped on you simultaneously by multiple bosses.

In investing, it’s even more complicated. If a fund manager is famous, he gets flooded with money. Other investors also try to copy him. A rumor mill circulates in the investing business, and if someone gets wind of a star manager buying or selling a stock, news travels fast. You might think that having copycats would be flattering. But it messes up a fund manager’s life and, ultimately, the money you make in the fund.

If traders (who buy and sell stocks for investors) spot the renowned manager buying a stock, they tell clients and their bosses. Those people want to make money, too, so they rush to buy the same stock. The result: The stock price goes up because of the volume of buying. So while the fund manager is in the process of buying the stock, he has to pay a higher price for the stock than intended. Likewise, if the manager starts to sell a stock and is noticed, others will copy him and bail out, too. So the stock plummets before the manager can sneak away from it. Consequently, if you own the fund being copied, you might make less money than you would if your manager was inconspicuous and could buy and sell stocks at the best prices for you.

More importantly, each manager has a certain style acquired over time in selecting stocks or bonds. Perhaps a fund manager understands how small company stocks generally act during cycles, so she can maneuver through good cycles with skill. She buys the promising stocks and avoids blowups, making mutual fund clients adore her. But she might not be as adept with large caps and might not even be allowed to buy them when they are the beneficiaries of a specific cycle. Or perhaps for years she’s been assigned to invest in healthcare stocks, and she looks brilliant while they are the popular stocks. But then along comes a cycle when investors hate healthcare stocks and are grabbing energy stocks. In that environment, her intuition and knowledge fail her, so she doesn’t shine during that particular cycle.

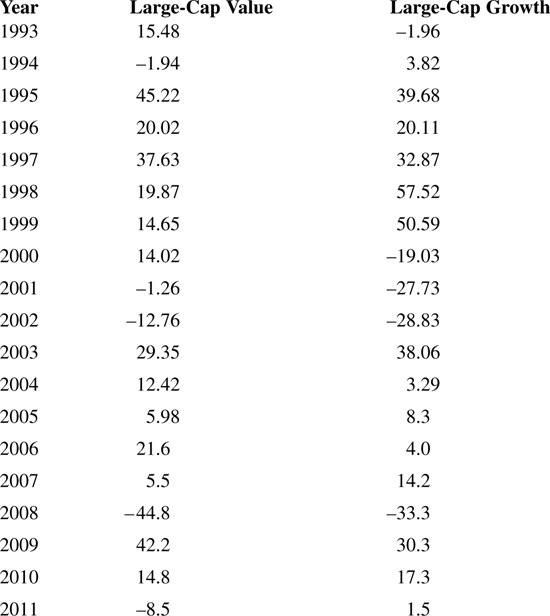

If you owned a Janus fund in 2000, you know what I mean. The funds seemed to be tremendous masters during the growth stock mania in the 1990s. But they became ugly losers in the early 2000s when investors ran away from technology stocks and other growth stocks and wanted safer value stocks—or companies that made widgets and drilled for oil. Janus managers lacked background in value stocks then. Growth stocks of all sizes outperformed value stocks from December 1997 to June 2000, with growth up 164 percent and value up only 41 percent. After 2000, the trend was the opposite. Growth stocks dropped 44 percent, and value stocks climbed 60 percent. That, of course, left even the savviest growth fund managers licking their wounds. Table 10.1 shows the fluctuations in the cycles of large-cap growth stocks and large-cap value stocks.

Table 10.1. Good and Bad Investment Cycles in Large-Cap Growth Stocks and Large-Cap Value Stocks (Annual Total Returns Through 2011)

Table based on data from The Leuthold Group.

This might bring you to the conclusion that all you need to do is find the all-around pro. But the academic studies suggest that the odds of finding the Warren Buffetts of the investing world are against you.

The One Proven Way to Success: Asset Allocation

Instead, the studies point to another investment approach that truly does work. And I’m going to teach you how to use it step by step so that you can make money over a lifetime without devoting more than a few minutes a year to the effort.

To get ready for it, I want you to start thinking the way you would when selecting doctors. When you need a doctor, you don’t pick one brilliant doctor and expect him or her to care for your every need. You pick one with the specialty you need. In other words, you wouldn’t go to an eye doctor if you needed heart surgery. And when you needed to have your eyes checked, you wouldn’t want the heart surgeon.

Both types of doctors are skilled; both are trained in the basics of the body. But one cannot step in for the other. As you go through life, you need a variety of doctors, with various specialties for all the needs of your body.

The same holds true for mutual funds. That’s why, if you went to a qualified financial planner with your list of mutual funds from a 401(k) plan and asked for help, the adviser wouldn’t focus on finding you the one right fund or the most brilliant fund manager. Your planner would check for well-managed mutual funds, but his primary focus would be on mixing and matching the funds on your list. He’d aim to hold a little of this and a little of that for you so that you would have all the specialties you needed: large-cap stocks, small-cap stocks, international stocks, and bonds.

The mixing process is called asset allocation. And although asset allocation is not nearly as glitzy as finding an investing whiz kid, it’s the one approach that studies have shown works over time.

Money manager Gary Brinson did a crucial study on this in 1986. He analyzed pension funds and found that the key influence on 94 percent of an investor’s return came from how the money is divided among stocks, bonds, and cash—or asset allocation. Only 4 percent depended on how well a manager selected stocks. Only 2 percent came down to how the manager “timed the market,” or figured out when to buy stocks and when to bail out.

Forget Heroes—Just Match

In other words, novice investors have the entire process backward when they focus on trying to find one brilliant stock picker with the Midas touch. And if you think you can’t be a good investor because you don’t know how to pick stocks, this should give you great confidence: Asset allocation is fairly easy—much easier than analyzing a stock. You don’t have to scrutinize company operations, follow the economy, or do any complex math.

It’s as easy as playing a matching game or following a recipe. Think of the matching games you played as a child. On one page of a workbook, you’d see a picture of a two-story brick home. Then you had to match that picture to one of four words in an adjacent list: car, house, girl, and dog. You’d draw a line from the brick home to the word house.

You don’t need much more than the ability to match in order to do a fairly good job investing your retirement savings—really! That’s why I taught you the terms in the preceding chapter: large-cap stocks, small-cap stocks, international stocks, and bonds. Those are the words you match to the names of funds on a 401(k) list, or the words you use to make a recipe fit for an IRA, a 529 college savings plan, or any other investment fund.

You combine the various types of funds into a mixture because each fund acts differently in cycles. When you jumble them together, one or two tend to buffer the blows from the fund that inevitably will be getting hurt or lagging.

Maybe the large-cap fund or the small-cap fund saves you from harm— or it could be the international fund or the bond fund. The point is that, right now, neither you nor anyone else knows which it will be. So when you buy the entire mixture and continue to hold on to the fund you adore and the fund you despise, you should be ready for the unpredictable changing seasons of the stock market. You will always have a fund that helps you relax while you wait for a rebirth of a laggard.

Start the Sorting—It’s Asset Allocation Time

Say that your employer gives you a list of funds for your 401(k) plan, or your broker gives you a list for an IRA. You have no idea which to choose. You see the Best Ever Large-Cap Fund, the Go Anywhere Small-Cap Fund, the Better Than Best International Fund, and the Wonderful Bond Fund. They all sound outstanding. Which do you select?

In the past, maybe you would have looked for one fund with a stock picker who had been touted in the news, but now you know that finding a hero alone is unreliable. So next, maybe you look at the returns for all the funds in your 401(k), hoping that one fund will stand out. You see that the Go Anywhere Small-Cap Fund was up 20 percent last year, whereas the Best Ever Large-Cap Fund gave investors only a 5 percent return. And the Wonderful Bond Fund was up only 1 percent.

So maybe you think the choice is easy. You will go with the winner, the one that gained way more than any of the others last year: the Go Anywhere Small-Cap Fund. That’s what many novice investors do. But you know now that’s the wrong decision, the road to destroying hard-earned money.

Instead, the right answer is to pick all four funds—large caps, small caps, international stocks, and bonds. The Best Ever Large-Cap fund might just look like a dud at the moment because the cycle at that particular time is not being kind to large caps and is bestowing wealth on small caps. But history shows that, with time, fortunes will reverse, and large company stocks will be the winners while investors temporarily shun the small company stocks.

You need all four types of funds to be ready for whatever the market cycles throw your way. That’s what the investment world calls asset allocation, or dividing your money into a variety of specific types of funds.

And that’s why you play the matching game, looking for the words you need on your fund list. Extra words in the fund names always get in the way. So as you play the matching game, you hunt for the keywords I taught you in the preceding chapter. You’ll find them within either the fund name or the fund’s description that accompanies the fund.

Within the name Best Ever Large-Cap Fund, for example, you merely focus on two words, large cap, and you match that fund to the amount of large caps that I give you in Chapter 11, “Do This.” You are going to start pouring fund types—or ingredients—into a recipe that will make your retirement savings grow.

After you have matched the large-cap fund to your recipe, you go back to your 401(k) list and then hunt for your small-cap choice. And there you find it. Buried within the name Go Anywhere Small-Cap Fund, you find the most important words: small cap. You are going to match a certain amount of that fund to the small-cap proportion of your recipe.

So let’s say that you’ve thrown an approximately correct amount of small caps into your 401(k) retirement success recipe. Then you move to the international fund and the bond fund, dropping the right quantities into your retirement fund.

That’s the process.

But what if you see a fund that doesn’t have keywords such as large cap or small cap in the name? That happens sometimes. Funds have names such as Fairholme and PIMCO Total Return. In that case, you have to probe a little deeper into the fund’s description in your 401(k) materials, maybe using the prospectus (the pamphlet that comes with the fund) or going to www.morningstar.com. At the Morningstar Web site, you can enter the name “Fairholme” or the symbol “FAIRX” for Fairholme in the white Quotes box at the top of the page. After you press Enter, you will see a page with a lot of information about the fund. Toward the top of the page, you will see Category and, next to it, Investment Style. Both tell you that Fairholme is a “large value” fund. In other words, you know that the manager picks large companies that he thinks are cheaply priced, or value stocks. You will also see four out of a possible five stars nearby and a 10-year history of solid performance. So if you wanted a large-cap value fund, this could be your choice. You would match it to your recipe.

Getting the Proportions Right

But now you might be wondering how to get the proportions right when you do the matching. That’s not difficult, either, given all the asset allocation models (or recipes) that are available to you. If you have a 401(k) plan, your employer might have a Web site or printed material with pie charts. A broker or financial planner might show you these, too. The charts might be identified in a brochure or on a Web site under the heading “Asset Allocation.” These are the recipes to follow, and the slices on the pie charts show you how much of each type of fund to use.

You might have seen these charts in the past and found them meaningless. They won’t be confusing anymore because now you can recognize the mutual fund names and will know how to match names on your mutual fund list to the corresponding slice on the chart.

Still, you might get somewhat overwhelmed because there are many different pie charts. You see a variety for a reason: How you divide your money depends on when you will need it and how nervous you get when the stock market goes through nasty cycles. In the next chapter, I help you identify the pie chart (recipe) that might be appropriate for you.

First, I want you to be aware of one important point: If you went to various financial planners, each would have a slightly different recipe, or asset allocation plan, for you. That might be unsettling; perhaps all the variations would make you worry about making a mistake. Maybe one says to put 35 percent of your money into large-cap funds and another says 38 percent. Instead of being nervous about imprecision, let it comfort you and empower you.

Asset allocation, or mixing and matching types of mutual funds, is essential. You must do it to be a successful investor. But the theory behind it is not so refined that professionals agree on precise portions of the various types of mutual funds. In other words, professionals generally agree that you need large caps, small caps, international stocks, and bonds, but they might deviate on the amounts by a couple percentage points.

Think of it like using a recipe that calls for a rounded teaspoon of sugar. Just what is “rounded”? It’s more than a teaspoon, yet whether you rounded the amount of sugar a lot or just a little, the recipe would probably turn out okay.

The critical point is that you use sugar. You don’t just leave sugar out of the recipe, and you don’t use a cup when the recipe calls for a teaspoon. So as an investor, what’s vital to you is that you use the full mixture—the sugar, or small caps; the flour, or large caps; international stocks, for variety; and, of course, bonds. The blending of the ingredients will make your money grow effectively over time.

It’s called diversifying. All it means is this: You don’t overdose on a single type of investment, but you hold a blend of investments so that you are ready for any cycle.

The Logic Behind “Diversification”

If you handed your money to most financial planners, they would not try to predict when the cycles would come and go or when a certain mutual fund would win or lose. Studies convince investment professionals that guessing tends to be folly. Instead, they simply decide on an appropriate “diversified” mixture of mutual funds for clients based on research showing that small caps, large caps, international stocks, and bonds take turns soaring and plummeting during cycles.

They figure that if they buy the right mixture for an IRA or 401(k), their client will get the advantage of the 47 percent upturn in small-cap funds in years such as 2003, when the good times just happened to hit without warning. After all, who would have expected such a windfall then? The previous year, a person with the same fund would have lost 20 percent and perhaps dumped the fund in disgust.

Likewise, large-cap funds can deliver delightful surprises and insulate people from losses that small-cap funds deliver as they go through vicious phases. For example, in 2006, small caps were sweethearts, growing money 18 percent and tempting investors to channel all their savings there. Then without warning, small caps made a Jekyll-and-Hyde move and started destroying money the next year. Large caps saved the day as they gained 5.5 percent and insulated people from the damage that would have hit their money if they had depended on small caps alone.

But it’s not always the large-cap stock funds that save you from destruction. The stock heroes of the entire decade that began in 2000 were small-cap value stocks. They gained 10.6 percent a year, on average, while large caps went through 10 years without recovering fully from the viciousness of technology stocks early in the decade and the barbarity of bank stocks late in the decade.

One piece to this approach might shock you. As cycles occur, and as any one of the mutual funds in an investor’s retirement fund takes a beating in a day, a month, or a year, most financial planners do not fixate on the moment or let it deter them from a well-conceived plan.

Planners just hold tight to the mixture of funds they created. They focus on historical studies showing that after many, many years, the large stocks in the mixture should climb about 8 to 10 percent, on average, annually—even if they are being brutalized at the moment. The small stocks should average around 12 percent, even if they are soaring much more than that at that point in time. And the bonds should smooth out the worst bumps, climbing at about 5.5 percent.

The professionals concoct the mixture based on historical studies that demonstrate how blending all the different categories provides a decent retirement after 20, 30, or 40 years of letting the mixture sit intact through ups and downs.

Proportions, however, are the key for the long-term outcome. Financial advisers determine which proportions are best for certain types of clients by using historical data. It shows them what various concoctions of stocks and bonds are likely to do.

They know that a person who relies only on stock funds during a five-year period could lose as much as 12 percent a year or make as much as 28 percent, because there already has been a point in history when this happened.

They know that they can soften the impact of a cruel stock market by putting 30 percent of a client’s money into bond funds and 70 percent into stock funds. With such a mixture, history tells them the worst loss during five years could be 6.3 percent a year, and the upside could still reach a delightful 22.7 percent.

To be even safer, planners know that they could put half a client’s money in bonds and half in stocks. Then the worst anticipated loss would be 2.7 percent a year during five years, if history repeats the worst cycle. And there still would be an upside of potentially 21 percent if history repeats the best period.

Could the future be somewhat different than the past? Absolutely. But the past is the best tool available to provide a guide to the future.

With this type of historical data, investment professionals pinpoint the combinations that best fit people at different points in their life. A 25-year-old needs a lot of stock to harness the power of compounding early and build a fortune. A 60-year-old needs to be more careful—perhaps dividing her money half in bonds and half in stocks to make sure she doesn’t lose a fortune in a stock market disaster on the verge of retirement.

This Isn’t About Math

This might sound like a complex endeavor, but it isn’t. Financial advisers don’t have to do elaborate calculations to incorporate history into plans for these various age groups. Brilliant professors and math geniuses have fed years of stock market data into computers and turned out some simple models. Those models show up in colorful charts with 401(k) and IRA materials, and they are all over the Internet.

Professionals and people like you have access to these so-called asset allocation models and can follow them without any more math than you learn in elementary school.

Although most people think they can’t handle any of this because it must require a math brain, what’s actually involved is quite different. If you went to a financial planner, he or she probably wouldn’t be doing equations. Instead, that planner would be trying to figure out your psyche.

Planners want to know whether you are going to panic in a market downturn and run away from the combination of mutual funds that they assembled for you based on a simple model. They know that, if you panic, you could lock in a tremendous loss and perhaps need decades to recover. That’s too costly for you, and they don’t want it to happen.

Consequently, if planners think you might flee your stock funds, they tweak one of the typical models for your age group a little, maybe reducing your exposure to stock funds by 5 or 10 percent.

This is critically important. Novice investors usually get this wrong. They tend to go for all or nothing—either all small caps or no small caps, all stocks or no stocks. In contrast, the professional tweaks—maybe up 2 to 5 percent or down 2 to 5 percent in a category of stock funds.

The same goes for scary periods in the market. The professional might move 5 to 10 percent of a person’s money out of stocks and into a money market fund to soothe a nervous client. But the professional tries to talk clients out of moving every cent to safety because the pros know that the cycle will change when you least expect it. And being there, ready for the change of seasons, is the sure way to make money.