11. Do This

Now you know how professionals think and what they try to do with your money. It’s time for you to do the same—to master the finishing touches. Asset allocation, or mixing and matching a variety of funds, is the most important move you will make as an investor. And you now have all the tools you need to do it well.

You already know what’s inside various mutual funds, what makes them soar and plummet in cycles, and how to match key terms such as large cap and small cap to your list of mutual funds. Now I’m going to show you how to select the appropriate proportions, and you will then be done. You will be a skilled investor.

We start with a classic mixture of funds. Investment professionals agree that a moderate asset allocation model divides retirement savings like this: 60 percent into stocks and 40 percent into bonds. This investment blend is comparable to the porridge that’s “not too hot, not too cold” in “Goldilocks and the Three Bears.”

From now on, think of the 60 percent stock/40 percent bond combination as a reliable asset allocation model that is just right if you aren’t greatly adventurous. Then venture off from that point, if you’d like, into a model that might be even better for you. As you read further, you will become competent at adapting the model to your particular age, years to retirement, and temperament.

The 60:40 mix is a good starting point in learning asset allocation. Over the years, knowing this classic allocation model will give you your guidepost for investing decisions. It can always be your fallback position if you are ever confused.

If you use it continually, you will be on a better track than most people. The math whizzes have shown that you can lose money with a 60:40 mix in a single year. But losing money for even two years in a row is unusual.

Asset Allocation Is Simply Matching

Let’s say that you have decided to sign up for a 401(k), or you want to overhaul a retirement account you have neglected.

Your employer hasn’t given you a recipe, or model, to follow. But it doesn’t matter. You now have the classic 60:40 stock and bond asset allocation model in your head, and you are going to use it as your recipe. You have your list of mutual funds on your desk, and you have a form to fill out. It asks you how much of your paycheck to invest in the retirement plan. It also asks you how you want to divide that money among the various mutual fund choices. You need to state your preferences in percentage terms.

Let’s say that you decide to put $100 from each paycheck into your 401(k) plan. So as you fill out your 401(k) form, you think of your $100 as 100 percent of your recipe’s mixture and start from there.

The next step is to hunt through the mutual funds on your 401(k) list, to start the mixing-and-matching process. Your 60:40 recipe calls for bonds. So you peruse your list of mutual funds and find only one diversified bond fund. It’s called the Wonderful Bond Fund.

“Wonderful!” you exclaim. “I’ve found it.” The only question is, how much? So you simply match that fund to the quantity you need in your recipe. Your decision is easy because the recipe tells you exactly what to do. You already decided you were going to use a classic 60:40 mixture for your recipe.

So you write on your 401(k) form that you will put 40 percent of your 401(k) contribution into the Wonderful Bond Fund. That’s $40 every payday.

You now have assembled 40 percent of your recipe. The bond portion is done. Next, you return to your list of 401(k) mutual funds to complete the second part of your recipe: pouring in the right amount of stocks. You know the quantity from your recipe—it’s 60 percent. You also know from the preceding chapter that a well-diversified large-cap stock fund is a key ingredient, a core investment to hold year after year.

You find one large-cap stock fund on your list of funds, the Best Ever Large-Cap Fund. You select it and follow your recipe by putting 60 percent of your 401(k) contribution into that fund, or $60 a payday.

You now have a classic 60:40 asset allocation—60 percent of your money is in stocks, and 40 percent is in bonds.

Your recipe is complete, and your 401(k) form now looks like this:

Wonderful Bond Fund: 40 percent

Best Ever Large-Cap Fund: 60 percent

As you go through life, you will have different actual funds in 401(k) plans or IRAs, but whatever they are, you can put 40 percent into a diversified bond fund and 60 percent into a diversified large-cap fund. If you keep this approach intact, with 60 percent of retirement savings in stocks and 40 percent in bonds, you will be more successful than most 401(k) investors.

But let’s say that you feel comfortable taking this a little further, and you should. We are going to fine-tune that 60 percent piece you put into stocks, making a slight change in your recipe so that you are ready for more cycles in the market. The basic recipe of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds is going to stay intact. But you realize that sometimes small-cap stocks do well and large caps are disappointing, and other times large caps win and small caps are scary. So you want to be prepared for both cycles.

I assume now that your 401(k) plan gives you a choice of one large-cap fund and one small-cap fund. Not all do. But say that you have those two choices. Then go through your list of stock mutual funds and find those that match the two basic U.S. stock categories: large caps and small caps. You will choose both based on a common practice in the investment profession: Typically, a financial adviser wants you to put about 70 to 75 percent of all your U.S. stock money into large caps because they are less volatile and make up a larger portion of the overall stock market than small caps. In fact, large caps make up roughly 70 to 75 percent of all the stocks in the stock market, so that’s where the recipe originates. You can simply copy it. When you have tucked large caps neatly away, you dump the remainder into small caps, which make up roughly 30 to 25 percent of the stock market.

Here’s how you would follow the recipe and sign up for 401(k) mutual funds—again, starting with the original $100 for your 401(k) plan contribution.

First, remember that the basic recipe is 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds. Begin by selecting bonds, filling 40 percent of your recipe with a bond fund. That is $40 on every payday.

Then you move to stock funds in the 401(k) list and decide how to allocate the remaining $60, or the 60 percent, that your recipe says should go into stocks. You state on your 401(k) form that you will put 45 percent of each 401(k) contribution, or $45, into a large-cap fund, and 15 percent, or $15, into a small-cap stock fund. (This might not look like 75 percent large caps and 25 small caps, but it is. Remember, you are simply dividing up your stock money, or $60, into the 75 percent large cap and 25 percent small cap concoction.)

That takes care of 100 percent of your contribution into your 401(k) plan. With the combination of large stocks, small stocks, and bonds, you are well diversified and ready for most cycles in the U.S. stock market.

For that 60 stock and 40 bond asset allocation, your 401(k) selection form now reads like this:

Whatever Bond Fund: 40 percent

Whatever Large-Cap Fund: 45 percent

Whatever Small-Cap Fund: 15 percent

All right, but let’s say that your 401(k) also includes an international fund; you know that sometimes foreign stocks do best, and in other cycles, U.S. stocks do best. You want to be ready for anything worldwide and partake in the global economy—smart!

In this case, let’s start fresh with your $100 contribution. First, put 40 percent, or $40, into a bond fund. But now you are going to think of your $60 stock portion with a fresh approach. You will think of dividing your total stock money, or 60 percent of your full 401(k) contribution, into two major categories: U.S. stocks and international stocks. And I recommend that you put roughly a third of all the stock money into international stocks.

With many countries going through a growth spurt recently, financial advisers have become increasingly interested in foreign markets. But advisers are debating how much money to channel there. Some say 50 percent because foreign markets make up about 53 percent of the globe’s stock market value. A few say no foreign investment is necessary because large U.S. companies sell products everywhere.

So feel free to tweak your foreign allocation a bit, if you’d like. But let’s say that you decide to put a third of your stock money into a solid, well-diversified international fund that insulates you from regional shocks by investing in many countries throughout the world. Then, given your $100 contribution to your 401(k), you would put $40 into a bond fund, $20 into an international fund, and the remaining $40 into the large-cap and small-cap U.S. stock mixture I previously described.

In other words, you’d put about a quarter of your U.S. stock money in small caps and the rest in large caps. Now your 401(k) form looks like this:

Whatever Bond Fund: 40 percent

Whatever Large-Cap Stock Fund: 30 percent

Whatever Small-Cap Stock Fund: 10 percent

Whatever International Stock Fund: 20 percent

You are nicely diversified and ready for cycles. With every paycheck, you will put $40 into bonds, $30 into large-cap stocks, $10 into small-cap stocks, and $20 into stocks throughout the world.

If you are offered a midcap fund, you can use that to diversify even a little more. In that case, leave everything intact on your recipe except your small-cap allocation. Divide the small caps in half, putting a 5 percent allocation of small caps into the mixture. The remaining 5 percent goes to midcaps.

You have a complex, well-diversified portfolio. Your 401(k) form would look like this:

Whatever Bond Fund: 40 percent

Whatever Large-Cap Fund: 30 percent

Whatever Small-Cap Stock Fund: 5 percent

Whatever Midcap Stock Fund: 5 percent

Whatever International Fund: 20 percent

That’s it. You’ve got the basics. You write those percents on your 401(k) form provided by your benefits office at work, and you can be done with the task. With every paycheck, your orders will be followed, and you will be ready for the various cycles of the market. You will stay with the plan regardless of market conditions, forging ahead even if one or more of the funds happens to be bleeding cash during an awful cycle.

Picking Within Categories

But what if you have more than one large-cap fund on your 401(k) list? How do you choose between them? If you find one fund that is described as a core fund, that makes your choice easy. It means your fund manager will blend various types of large stocks for you so that you will be ready for a variety of cycles and won’t be overly risky. You will have some risky, fast-growing stocks but also more dependable, slower-growing value stocks.

To find such a fund, look for words such as core or blend in the fund’s name or description. But you might not be lucky enough to see that simple language. The fund description for a core fund might instead tell you that the fund looks for capital appreciation and selects both growth and value stocks.

If you are lucky, you will find a fund called a “Standard & Poor’s 500 Index Fund” or a “total stock market index fund” on your fund list. If you do, either of these will serve you well as a core fund. In the next chapter, I explain more about why these two particular funds are usually excellent choices.

But if you don’t have a core fund, you will probably have to choose between a large-cap value fund and a large-cap growth fund. The growth fund will be more daring. In certain years, you will make more money, and in others, you will lose more money than you would in a value fund. Generally, the value fund gives you a more stable ride, with less shocking losses than in a growth fund.

As I said in Chapter 9, “Know Your Mutual Fund Manager’s Job,” the value fund—or the tortoise in the “Tortoise and the Hare” race—wins over many years of investing. But even if you can’t figure out whether you are looking at a tortoise or a hare, don’t get hung up on this decision and fail to act. Get started with a well-diversified large-cap fund, and you will be headed in the right direction.

Still, if you are up to the task and willing to fine-tune your choices more completely, start trying to identify which of your choices is large-cap growth and which is large-cap value. Let the matching game begin. Look in the fund name or description for these words to find a growth fund: growth, or maybe maximum growth or aggressive growth. Typically, a maximum growth or aggressive growth fund is riskier than a growth fund.

Value funds often have words such as income or low cost in the name or description. The description might also tell you that the fund selects stocks that pay dividends. Typically, when stocks pay dividends, that gives you a certain level of stability—insurance against wild ups and downs. (Think of dividends a little like the interest you get on a savings account, except that dividends are never guaranteed. The company can increase a dividend, leave it the same, or take it away. (In the financial crisis and recession of 2008, companies were under financial pressure, so many took away the dividend or stopped paying as much to investors as they had previously. So just when investors desired the insulation dividends can provide, they lost it.)

Okay, let’s get back to the matching game. You will find the same growth and value labels on both small-cap funds and large-cap funds. So what do you do now that you can spot them? If your head is spinning with growth and value, and you are asking what’s best for you, take a deep breath again and be assured that there is a simple way to handle all of this. In fact, if you went to a financial planner for help, he or she would likely take the simple route. The planners don’t know any better than you do whether the cycle in a single year will favor a growth or a value fund. So they don’t try to figure it out. Instead, they get the stock portion of portfolios ready for any cycle. They simply divide it half growth and half value so that the investor will be ready for the ups and insulated somewhat from the downs.

So let’s say that your 401(k) plan doesn’t have any core funds in it. Instead, you are given two large-cap fund choices: a large-cap growth fund and a large-cap value fund. Likewise, you are given two small-cap fund choices: a small-cap growth fund and a small-cap value fund. What do you do? You can just divide your large-cap money 50 percent into growth and 50 percent into value. Do the same with small caps.

Here’s what it looks like in money: If you are putting $45 into large caps, $22.50 will go into a large-cap growth fund and another $22.50 will go into a large-cap value fund. If $15 is going into small caps, you will put $7.50 into the small-cap growth fund and another $7.50 into the small-cap value fund.

That’s the process. That’s as elaborate as you have to get.

You Don’t Need to Use Every 401(k) Fund

Your 401(k) might give you more choices than I have described here. You don’t have to use them all. The key is to match the necessary categories, not to use all the funds. Just to reiterate, the necessary categories are bonds and stocks. And for stocks, you want international, large cap, small cap, and maybe midcap. Fill each of the categories with one core fund that blends growth and value stocks, and you will be on the right track. So that’s four or five funds. But if your plan doesn’t offer a core fund, you can pick one fund for large-cap growth, one for large-cap value, one for small-cap growth, and one for small-cap value.

If you do this, you are far beyond the average person. You are assembling your retirement savings the way a financial planner would if you went to one for help.

What’s Your Age: 20, 30, 40, 50, or 60?

Depending on your age and how you will feel when conditions get really ugly in the stock market, you might want to alter the quantities in your recipe somewhat. Think again about the rounded teaspoon for your recipe—a close but inexact measurement. Again, there are no absolutely exact measurements with investments because only you can figure out just how much nerve you will have during scary cycles.

But here are some rules of thumb. If you are in your 20s and 30s, and if history makes you comfortable that you will recover from the scariest of stock market downturns, deviate from the classic 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds portfolio I have described. Go right ahead with a more aggressive approach to stocks: cutting back on bonds. True believers with no fear of the stock market can even eliminate bonds altogether in their 20s, but should add bonds a little at a time each year as they age so bonds provide insulation from a market crash.

Before the 2008 stock market crash, financial advisors were pushing young investors to put 90 to 100 percent of their retirement savings in stocks. They argued that when people are in their 20s, they should be more worried about running out of money in their old age than incurring maybe a 20 or 30 percent loss in the stock market when young. And stocks tend to be the way over many years to give the biggest boost to your money.

Yet the 57 percent crash in the stock market between the end of 2007 and early 2009 was sobering for just about everyone, including financial advisers. Many had been blinded by the unusual grandiose gains of the stock market in the 1980s and 1990s and ignored the fact that stocks are capable of furious losses at times. As reality hit in 2008, most individuals lost their nerve as stocks were careening toward what looked like oblivion. Many people went to financial advisers begging for a quick route out of stocks. So advisers now tend to recommend some bonds even for 20-somethings, to keep them calmer in brutal times.

If you came through the crash confidently, you might be among those who can take substantial risks, perhaps putting all or almost all of your retirement savings into stocks.

Yet that doesn’t mean investing in just one specific stock or one type of stock fund. That’s asking for trouble and leaving you way too vulnerable to a corporate mishap or bad cycle in the market.

It does mean taking steps to cushion the impact of cycles—in other words, dividing your money into large caps, small caps, and international stocks. It also means keeping a mixture of growth and value, not the hot mutual fund of the day. You can get growth and value blended into core funds, or you can select growth and value individually.

So if you are 22 and signing up for a 401(k) plan for the first time, and you want to be 100 percent in stocks, your mixture of funds could look like this:

Large-Cap Core Stock Fund (maybe a Standard & Poor’s 500 Index Fund): 50 percent

Midcap Core Stock Fund: 8 percent (or Midcap Growth 4 percent, Midcap Value 4 percent)

Small-Cap Core Stock Fund: 8 percent (or Small-Cap Growth 4 percent, Small-Cap Value 4 percent)

Diversified International Stock Fund: 34 percent

Sometimes, with gutsy 20-something-year-olds who have seriously contemplated the effects of an awful stock market, financial advisers lean toward more small caps. Instead of putting about 75 percent of the U.S. stock portfolio into large caps and 25 percent in small caps, the advisers might go to 30 percent in small caps or even somewhat higher. Some also favor small-cap value funds over small-cap growth funds because, historically, value has outperformed.

Regardless, of these alterations, the closer you get to your retirement years, the more conservative you should become. The idea is to cushion your savings so that a stock market tsunami doesn’t do so much damage that you will have trouble recovering in time for retirement. So as you go into your 30s, you slowly add some bonds to your investment portfolio.

By age 35, your 401(k) mutual fund selections and IRA would look about like this:

Large-Cap Stock (maybe a Standard & Poor’s 500 Index Fund): 38 percent

Midcap Stock: 6 percent

Small-Cap Stock: 6 percent

International Stock: 25 percent

Bonds: 25 percent

During each year after age 40, consider moving another 1 percent into bonds and taking it out of stock funds. The process of slowly moving money away from stocks continues into retirement. Remember as you do this to stay diversified, following roughly the portions of large, small, and international stocks I have provided.

At about age 55 or 60, financial advisers often suggest a classic combination of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds, although since the 2007–2009 market crash, there is a focus on being even more conservative with stocks close to retirement. I lean toward putting half your money into stocks and half into bonds at around age 60. To be even safer in troubled times, consider only 40 percent in stocks and 60 percent in bonds, but realize that, by cutting your risk in bad times, you impede the growth you will get in good times.

Consider the full cycle of the 2007 crash—both the horrible period and the healing period that comes after every stock market panic. People with a classic portfolio of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds lost about 29 percent of their nest egg by the worst point in the 2007–2009 crash. A $10,000 investment became only about $7,100. People with half in stocks and half in bonds lost 22 percent; their $10,000 turned into $7,800.

Both approaches insulated people from the 57 percent decline that stocks delivered, but many were horrified at the extent of their losses nevertheless. They imagined they’d be eating cat food in retirement. Yet those who dared to hold on to their 60:40 mixtures of stocks and bonds learned a valuable lesson. Although the crash conjured up images of irreparable devastation, within about 18 months of the scariest point, people regained all that they had lost. By the end of 2011, they had about $11,800. Those with the 50:50 stock and bond mixtures had about $12,500.

In other words, diversification works, and ratcheting back on risk close to retirement works, although it does not insulate you completely from damage during awful cycles. Unfortunately, not enough baby boomers realized this ahead of the 2008 crash. One in four close to retirement had 90 percent of their money in stocks and suffered the full fury of the market storm.

Individuals close to retirement must realize that they are in a very different position than people saving for retirement in their 20s, 30s, 40s, and even 50s. Once you retire and stop working, you typically have to remove money regularly from your savings to pay for your living expenses. That means that the money you remove cannot wait for the healing cycle that will inevitably arrive in the stock market. So the destruction from the stock market is multiplied by the fact that you are also removing money from your savings at the worst possible time, robbing your nest egg of the opportunity to let that money heal.

That’s a very different situation than for people who are saving for retirement in their 20, 30s, 40s, and 50s. Because working people aren’t touching the money in their 401(k) or IRA, it remains there to heal completely. Furthermore, if they keep adding money during scary periods, that money usually gets the benefit of gigantic gains when the healing process begins. On average, the stock market climbs about 48 percent within a year of hitting bottom.

Because you can be so vulnerable after you start spending money for retirement, I suggest that, about five years prior to retiring, people meet with a certified financial planner to make sure their finances are positioned for good times and bad times.

I recommend going to a fee-only financial planner, and I provide tips on selecting one in Chapter 15, “Do You Need a Financial Adviser?”

Doing Your Gut Check

As you look at asset allocation models that are appropriate for your age and the number of years you have remaining until retirement, don’t delude yourself about your personality. Try to force yourself to consider how you would actually act under certain stock market scenarios.

People have difficulty forcing themselves to do this when they are making money in the stock market. Yet every time the market falls sharply, my phone mail system fills up with calls from anxious people.

In June 2006, for example, Carol, a 50-year-old Chicago psychiatrist, was among the terrified callers. She had just looked at her international fund, and she had lost about $5,000 in a few days. She wanted to know whether she should flee.

It was only natural that her fund would be down. The international markets had gone through a sharp downturn. In just two weeks, stocks in emerging markets of the world, such as Pakistan, Malaysia, and Venezuela, had crashed about 20 percent. It was troubling to investors, but it should have been expected. For two years, emerging market stocks were the sweethearts, bestowing great gains on investment accounts. The herd had piled in and then awoken in May 2006, concluding that the world was growing, but not enough to support the stock prices people had paid. So the stocks fell for a while as investors became more realistic.

Carol didn’t know about cycles and didn’t understand that she had been a part of an international stock craze during the previous couple years. All she knew was that she had put almost half of all her retirement money into an international fund, and it was quickly performing a disappearing act.

I told her about cycles and explained that the economies of the world would keep growing. Then I also explained that she had overdosed on international funds during the best of times. She needed to make a change— but not because of the loss she had just taken. She simply did not have the gut for the beating investors take whenever they’ve concentrated heavily on a certain investment.

Typically, about a 20 percent allocation in international funds would have been about right for a person like Carol, about 15 years from retirement. Yet the market had just forced her to do a gut check, and it demonstrated that perhaps even 20 percent in international stocks might be too much for her.

I told Carol not to flee her diversified international stock fund entirely, but to tweak the usual 20 percent model so that she would feel better, maybe using a 15 percent allocation in a foreign stock fund. With that approach, she would still diversify her stocks, tapping the world and the United States, but she would be less susceptible to the shocks she could not stomach.

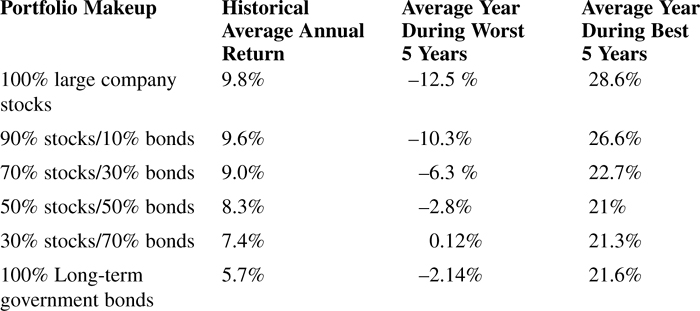

When you do your gut check, you can use market history to quiz yourself about how you might respond. Go back to Chapter 9 and look at the best-and worst-case scenarios for the different types of mutual funds, and look at Table 11.1. Ask yourself how you would deal with the worst shock, such as losing an average of 12.5 percent every year for five years in an all-stock portfolio, or 10.3 percent with almost all stocks. Realize that, when it’s happening, you don’t know when it will end.

Also consider the mixtures I have advocated. Say that you put 70 percent of your money into stocks and 30 percent into bonds. The worst year for that model has been a 32 percent drop. If there is about a 30 percent drop in the future, your $1,000 will turn into about $700. I hope you now know enough about cycles and history to hold on to diversified portfolios of mutual funds, knowing that, with time, you will recover.

Table 11.1 should help you focus on the long run so that you can get through tough times and make your money grow. But be honest with yourself now rather than amid the carnage. If you tweak your 70 percent stock allocation—maybe to 65 or 60 percent—that could take the edge off of downturns, allowing you to stomach them and come out better in the long run.

Table 11.1. How Stocks and Bonds Work Together—Compound Annual Rates of Return in Percents, 1926–2011

Source: Ibbotson Associates, a Morningstar, Inc., company

A Reality Check for Fear: The Losses of the 2007–2009 Crash

I just allowed you to peruse the averages because averages tend to be the favorite method used by the financial industry to show good times and bad. However, I think that averages fail people. When individuals are in the midst of seeing their futures exploding in a horrifying stock market, they don’t think in averages. They think in real dollars—or maybe I should say that they feel their losses in dollars. They observe their money disappearing. They contemplate utter devastation.

So I am going to take you through a journey that will let you see a horrific scene in real dollars. I am going to walk you through the scariest time in the stock market since the Great Depression so that you can feel the pain, see the ultimate outcome, and give yourself a chance to test your gut in real dollars.

I think of the stock market crash of late 2007 to early 2009 as the period in which virtually all Americans with 401(k)s and IRAs lost their innocence. It unveiled with brutal force the naive thinking of two prior decades, when people ignored the wisdom of combining stocks and bonds. Too many believed in the 1990s that they could plop a little cash into just about any stock mutual fund, earn 20 percent a year, and assume the money would be theirs for life.

When the illusion burst in 2008, and people saw carnage in their 401(k)s and IRAs, my telephone rang continually at my Chicago Tribune office. People sobbed as they asked me how to salvage their retirement and college funds. One woman told me she had just vomited. Another told me she didn’t know if she should worry more about the stock market or her weight because she’d been eating chocolates constantly to calm her nerves. Almost every caller blurted out, “I’ve lost everything.”

In fact, they had not lost everything, but it felt that way—partly because the losses seemed unbearable financially and partly because there was no end of the devastation in sight as the cycle played out on its own hidden schedule. Perhaps most important was the shock as their 401(k) and IRAs were doing the unimaginable.

Because individuals were taken by surprise, they panicked. They lost confidence in their ability to handle their own investments, they lost trust in their advisers, and, in many cases, they swore they’d never touch stocks again.

But the reality wasn’t as bad as some people assumed. If they followed the precepts of good investing and combined stocks and bonds, most combinations saved people from ruin and positioned them to get back to even and start making money again within 18 months or less of the horrific losses. Even people who had invested 70 percent of their savings in the stock market were back to even by the end of 2010.

So I show you here exactly what happened to various mixtures of stocks and bonds during this unnerving period so that you see that each combo behaved differently during one of history’s worst cycles. My hope is that it will help you decide what mixtures of stocks and bonds might fit your gut. By looking at these mixtures, you will see that blending stocks and bonds together matters a lot. You will see that bonds insulate your money from destruction, but not entirely. Most important, you will see how investment combinations allow you to recover with time.

Nothing ever plays out in the future exactly like the past, so keep that in mind as you review these combinations. Also realize that if you ever live through an alarming period, you won’t know at the time whether your losses will be as bad as 2009 or even worse. You won’t know when the decline in your money will stop, but at some point, the decline will stop.

So take a look and test your resolve. The numbers you are about to see here are real. I am providing very simple portfolios I assembled using actual months from Morningstar’s database. The stock portion simply is the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index of 500 large companies ranging from Apple to Exxon, Procter & Gamble, and Wal-Mart. The bond portion is long-term U.S. government Treasury bonds, or bonds that mature in 20 years.

Assume that it’s late 2007, you have no idea what’s about to happen, and you invest $10,000 in one of the eight ways you see here. This is what actually would have happened to you.

The Scary Period

First, look at the market collapse. I assume that you invested $10,000 at the start of October 2007 and held on all the way to the worst month, March 2009. At that scary time, you would not have had any inkling that the market was done falling and the pain was about to end. Here’s what would have been left of your original $10,000 at the worst point.

100 percent in stocks: You lost roughly 50 percent and your $10,000 became about $4,980.

80 percent in stocks and 20 percent in bonds: You lost about 40 percent, and $10,000 became about $5,980.

70 percent in stocks and 30 percent in bonds: You lost about 34 percent, and $10,000 became about $6,540.

60 percent in stocks and 40 percent in bonds: You lost about 29 percent, and $10,000 became about $7,140.

50 percent in stocks and 50 percent in bonds: You lost about 22 percent, and $10,000 became about $7,780.

40 percent in stocks and 60 percent in bonds: You lost about 15 percent, and $10,000 became about $8,480.

30 percent in stocks and 70 percent in bonds: You lost about 3 percent, and $10,000 became $9,705.

100 percent in bonds: You gained almost 18 percent, and $10,000 became about $11,775.

The Healing

Next, look at where you would be if you had allowed your money to heal. These numbers include the same mixture of stocks and bonds that you just saw. But now I run your $10,000 through the cycle, from the very beginning of the downturn in 2007, through the worst losses, and finally through the healing phase.

I assume that you put $10,000 into the stock market when there was no sign of trouble at the beginning of October 2007. Then you rode the market all the way down and maybe were scared almost senseless in March 2009. But instead of yanking your money, you simply let it sit there to go through the healing phase. Three years after the scariest point, you had taken advantage of stocks soaring about 98 percent. As a result, your original $10,000 would look like this by March 2012:

100 percent in stocks: Your $10,000 would be about $9,865.

80 percent in stocks and 20 percent in bonds: Your $10,000 would be about $11,110.

70 percent in stocks and 30 percent in bonds: Your $10,000 would be about $11,725.

60 percent in stocks and 40 percent in bonds: Your $10,000 would be about $12,340.

50 percent in stocks and 50 percent in bonds: Your $10,000 would be about $12,945.

40 percent in stocks and 60 percent in bonds: Your $10,000 would be about $13,530.

30 percent in stocks and 70 percent in bonds: Your $10,000 would be about $14,100.

100 percent in bonds: Your $10,000 would be $15,660.

In other words, an all-stock portfolio was still down 1.4 percent after all that time, but despite the terror on the way down, every other combination was growing your money again.

Beware now of jumping to the conclusion that you might as well invest 100 percent in bonds because they did better than stocks during this period. If you come to that conclusion, I have failed you. Instead, recall a critical lesson of investing: Cycles happen in every investment—stocks, bonds, gold, homes, you name it.

I showed you these combinations of stocks and bonds so that you see how the mixture pulled you through this cycle and ended up growing your money. It’s important to know that this cycle yanked stocks and bonds in unique ways, but combining them worked.

Bonds were abnormally strong because panicky people poured massive amounts of money into bonds when they got scared, and that caused the value to soar. Also, the Federal Reserve helped by tinkering to help the economy. So don’t expect bonds to always deliver gains as robust as during this period. More often than not, stocks grow your money more than bonds over long periods of time, and bonds hold up better than stocks amid trouble.

Even in the period after the stock market crash, stocks left bonds in their dust. As is typical after a crash, stocks soared as fear started to fade. Over three years, stocks gave people gains of about 98 percent, while bonds delivered 33 percent. But remember, the average for long-term Treasury bonds is a 5.7 percent gain annually, not the huge jumps that happened during this unusual time period. Most important, know that bonds suffer losses, too. In 1999, for example, investors lost 9 percent in bonds.

So I hope the message you take away from this is that stocks and bonds act differently in cycles, and that’s why you hold them both. The only question is, how much of each?

The Easy Rule of Thumb

As the years go by, sometimes you won’t have an asset allocation model to follow. You might see articles that refer to an old-style, easy rule of thumb that people use as a guide. The approach is to subtract your age from the number 100. That tells you what percentage you should invest in stocks, while placing the rest in bonds.

So say that you are 60. That would mean only 40 percent in stocks and 60 percent in bonds. Currently, with people living into their 90s, the old rule of thumb is considered somewhat outdated and too conservative. Some advisers argue that you should subtract from 120; others claim that subtracting from 100 still makes sense.

You could follow another rule of thumb, too: Tweak your typical asset allocations up 5 percentage points if you think you are braver, or down 5 percentage points if you feel more scared than the ordinary person. Again, there’s not an exact answer. There’s only an answer that’s close to appropriate, one that will make you comfortable. The portfolios of stocks and bonds I provided earlier will help you feel your way through your comfort zone.

Just avoid these common mistakes: waiting to invest because you can’t decide, being overly conservative when you have years to go before retirement, or swinging for the fences at any age—especially when retirement is just 5 or 10 years away. In other words, depend on diversifying your investments instead of counting on one stock or type of fund. Remember to tweak the proportions by a few percentage points instead of betting all or nothing.

Starting an IRA

Choosing mutual funds for your IRA isn’t as easy as for a 401(k), because your choices are vast. In a 401(k), your employer gives you maybe up to a dozen choices, so your selection is relatively easy if you play the matching game I just described. It’s as easy as looking at your list of maybe a dozen funds, spotting words, and slotting five to 10 of your funds into the pieces of an asset allocation model.

With IRAs, if you look at all the mutual funds available, you might indeed be overwhelmed. After all, more than 8,000 different funds exist. But you don’t have to bother with most of them. I give you some shortcuts in the next chapter, and you might want to go back to Chapter 9 for some mutual fund suggestions.

For now, I just want you to understand that the same step-by-step approach I laid out for mixing and matching funds in a 401(k) applies to an IRA. So if you don’t have a 401(k) and you skipped the previous explanation, go back and read it. The principle of using asset allocation and mixing and matching types of stocks applies to all your retirement savings. It’s easy, and academic research proves that it’s the one approach to investing that works.

You play the matching game with large caps, midcaps, small caps, international funds, and bond funds whether they are in your 401(k), your IRA, or any other account that is aimed at retirement saving. The key isn’t the label on the account. The key is the purpose it’s destined to accomplish. In other words, you are saving for retirement, so use the models I’ve provided for any IRA.

If you are in your 20s and starting your first IRA, however, you won’t be able to follow the model I have provided you from the outset. With time, you will position your savings in line with the beginning model.

Say that you are starting with just a $1,000 contribution. There’s no need to divide that into four different mutual funds. In fact, many mutual fund companies won’t let you because most don’t accept $250 contributions. Begin the first year by investing in a fund that will serve as your core investment for your lifetime, a mutual fund you will buy and hold year after year. In other words, start with a diversified large-cap U.S. stock fund, preferably a low-cost Standard & Poor’s 500 index fund or a Total Stock Market Index fund, described in Chapter 13, “Index Funds: Get What You Pay For.”

Then the next year, you might put another $1,000 into that same large-cap core fund in your IRA. You could do this again the third year. But after that, you’d take another $1,000 and buy your next fund: a diversified international fund. Then the next year, you could take another $1,000 and buy your next fund: a diversified small-cap fund. If you originally bought a total stock market index, you wouldn’t need a small-cap fund because you would already have large stocks and small stocks in your single fund. (Learn more about this topic in Chapter 13.)

Over time, you will be working toward having a portfolio made up approximately like this:

Large-Cap Fund (perhaps a Standard & Poor’s 500 Index Fund): 50 percent

Midcap Fund: 8 percent

Small-Cap Fund: 8 percent

International Fund: 34 percent

You don’t have to get any more elaborate than this if you just buy diversified funds. But if you want to fine-tune even further, as the years go by, divide each of the pieces in half, putting one half into a fund with a growth approach and one half into a fund with a value approach.

Remember, although you might start out in your 20s or 30s with just stock funds, you should begin buying individual bonds or a bond fund as time goes on. So in your 50s, having 60 percent of your retirement savings in diversified stock funds and 40 percent in bonds would be a solid approach.

If all this mixing and matching is driving you nuts, you will find a shortcut in Chapter 14, “Simple Does It: No-Brainer Investing with Target-Date Funds.” What’s important before you head to that shortcut, however, is to understand the keys to investing that I am laying out first so that they always steer you away from an explosive investment, calm you at scary moments, and guide you into an appropriate mixture of funds.

Avoid Market Timing

When investors discover that the market goes through cycles, they come to a fairly logical conclusion: They vow to keep their eyes open and bail out of stocks as soon as they see hints of danger emerging.

Avoiding trouble works well in many aspects of life. But it’s virtually impossible in investing, even for the savviest of professional investors. If you doubt this, consider September 11, 2001. Who would have predicted that terrorists would attack the World Trade Center and that the stock market (Dow Jones Industrial Average) would fall 14.2 percent in just five days? Or consider March 2000, when the stock market was shooting straight up. Investors thought investing was a no-brainer, that they would make money in the stock market forever. People were taking equity out of their homes to put it into the stock market just before it crashed. Little did they know that the stock market was about to fall 49 percent.

Perhaps you feel that you were the only fool in this debacle and that the pros know better. But it’s not true. Professional investors who manage people’s money might be skilled at asset allocation or shine at picking stocks and mutual funds. Yet even the best of them are lousy market timers—in other words, they don’t know when to get into stocks or when to flee.

College finance professors have done numerous studies to see whether market timing works. And they have come up with little evidence that it can be done successfully over time. In one study, a researcher examined the track record of 32 market-timing newsletters over a 10-year period. Not one beat the broad stock market. The reason is easy to understand. Even if you are astute enough to get out of the way of trouble initially by withdrawing from stocks, you probably will miss the next surge up. And that’s no small matter. Typically, investors make most of their money over a very few days. If they have put their money into safekeeping outside the stock market, they might miss those very few days.

If you think a couple days might not matter, consider research done by respected investor and author Peter L. Bernstein. In The Portable MBA of Investment, he notes that if the average investor missed just 10 of the very best days in the stock market over a 9-year period in the 1980s, his or her return would have been reduced by a third. Removing just 30 of the best days would have cut returns by 70 percent.

Most people make a terrible mess out of their own money by practicing market timing—or trying to catch what’s hot or moving away from a falling stock market. They think that the market is safe when it isn’t. They think that they should stash money in safekeeping when it’s time to invest again, or they move from one fund to another trying to find the elusive best one.

In March 2009, after the stock market had declined 57 percent, the widespread view among professional investors was that doom and gloom was far from over. That view was wrong, and most fund managers that I interviewed months later said they wished they had been braver when there were stock deals of a lifetime in early 2009. As they waited for signs that the stock market was recovering, brave investors bought stocks, so the great deals were gone by the time most investors felt safer.

The Impact of Market Timing

Fear of having a mishap as an investor sometimes keeps people from doing what’s prudent. They wait for the right time to invest and then end up waiting forever because they can always spot a potential threat. If you are among them, you might be reassured by some research done by Charles Schwab. Analyst Mark Riepe looked at four different hypothetical investors who took different approaches to market timing during 20 years from 1976 to 1996.

First, he looked at the person who ignored market timing and just put $2,000 into the stock market every year on December 31. At the end of 20 years, that person had accumulated $265,308. Then he looked at the person who had perfect timing and just happened to hit the best time to invest during each of the past 20 years. The results were good: $283,445. But the person who tried to buy stocks only during periods that looked promising and then accidentally blew it by investing just before a crash each year did the worst: $242,182 after 20 years of investing.

The lesson is this: If you knew you could time the market right, it would be worthwhile. But since you can’t, automatically investing money each month or each year should provide you comfort. Having $265,308 after 20 years isn’t bad when you are simply investing $2,000 a year. Also keep one more of Riepe’s findings in mind: The person who was afraid he’d make a mess of his money in the stock market and just put his $2,000 a year into safe U.S. Treasury bills ended up with only $85,708 at the end of 20 years.

So instead of trying to time the market, do what financial planners do for their clients: Decide on the asset allocation that seems right to you, keeping in mind that if you use a teaspoon rather than a heaping teaspoon, you will still be fine. If you get nervous during a downturn and can’t take it, make small changes, maybe shifting 5 or 10 percent out of stocks and into a money market fund instead of yanking all your funds and cowering in a money market fund that pays almost no interest.

I can’t emphasize this enough. As novice investors have called me over the years, they have repeatedly made one common mistake: betting too much money on either ups or downs in the market. If they think times are great, they put everything in hot stocks. If they think times are scary, they naively move everything to safety. Instead, think of tweaking, using what professionals sometimes call “tactical” changes, with 5 percent or 10 percent of your money. Do it if it makes you feel better, but realize that your timing will probably be off.

Also be aware that the stock market does fall. In fact, it falls at least 10 percent or more every nine months, and 20 percent or more every 3–4 years. It can get very ugly, as with the 2000–2002 drop of close to 49 percent and the 2007–2009 drop of 57 percent. But throughout the past 86 years, the market has been climbing, not dropping, about 70 percent of the time. And that has turned $1 into close to $3,045.

Dollar-Cost Averaging

Because investors get nervous during the periods when the market falls just after they have invested money, financial advisers often tell people to follow a process that is less nerve-wracking than simply dumping a large sum of money into the market at one time. The approach is called dollar-cost averaging.

This is the process that’s ingrained in the 401(k) system. Dollar-cost averaging means that, with every paycheck, you put a little money into your investments.

Because you do this with each paycheck over 20, 30, or 40 years, sometimes you will get great deals during low points in the stock market, as in early 2009. That’s when the stock market was just about ready to start climbing about 100 percent. If you invested routinely in early 2009, you captured that gain even if you were afraid and had no insight into the stock market. Of course, with dollar cost averaging, sometimes you will be putting money into the stock market at times when you will lose, as in 2007. That’s when the stock market was about to plunge 57 percent.

Investing in 2008 was traumatic, and many took a break and avoid losses. But over a lifetime of investing dollar cost averaging tends to be a sound approach. It is done more for emotional reasons than any other purpose. It forces investors to keep investing money when their gut says no. And in the long run, that pays off.

Rebalance

Instead of market timing, a discipline that professionals use increases the chances that you will benefit from highs in the market and not suffer severely in lows.

It’s called rebalancing. To do it, you look over your retirement accounts once a year to see which funds have surged in value and which have lagged. Then you remove some of the money from the hottest funds and move it into the slowest funds.

You go back to your original recipe, or asset allocation, to see whether you need to do this.

Let’s say that you were working off a very simple model, the classic 60 percent in stocks and 40 percent in bonds. And say that, during the past year, bonds have been the place to be and stocks have been lousy. You have lost so much money in your stock funds that your stock allocation is now down to 50 percent, and your bond allocation has grown to 50 percent of your overall portfolio.

You rebalance by taking your bond allocation down to about 40 percent again by removing some money. You move that money into your stock funds so that you have 60 percent of your money in stocks, matching your original model.

At that point in time, making a move like this will be hard to stomach. You will think that stocks are going to be scary because they have been scary. But if you think of cycles, you will appreciate the concept behind rebalancing. Eventually, the cycle is going to turn—and when it does, you will get the benefit of having 60 percent of your money in stocks. Best of all, you moved some money into stocks when they were cheap and neglected. In other words, you bought the stocks low and will get a chance to sell when they are high during the upturn in the cycle. It’s a bargain hunter’s delight.

What You Can Control

Ironically, a common practice that makes novice investors feel cozy is, in fact, one of the riskiest mistakes.

When they look over their list of 401(k) choices, they see one unfamiliar fund after another, so they go with what they think they know best: the stock of the company that employs them. They load up their retirement fund with it.

It’s like playing Russian roulette with retirement savings. Academic studies show that choosing a single stock frequently sets you up for disaster. Typically, the person looks around his surroundings—seeing machinery, offices, and thousands of people hard at work all over the country or even around the world—and says to himself, “What could go wrong?”

Need I say it? United Airlines once looked like a corporate titan to its employees and to investors. Yet it had to file for bankruptcy, making its stock worthless. Kmart once looked like the most powerful retail chain in the country, but it went into bankruptcy a few years ago, leaving investors with worthless stock.

Enron was one of the hottest stocks of the 1990s. The press wrote glowing stories about the company, and employees at Enron filled their retirement funds with the stock, figuring they could retire at 50. Corporate executives encouraged them to do it, singing the company’s praises even when it wasn’t true. Then reality caught up with the company. Much of the glowing news was based on fake numbers, and the company collapsed. People who once thought they’d retire at 50 were wiped out. Their dandy nest eggs had turned to zero.

So if your employer lets you buy the company’s stock in your 401(k), follow the lead of experts who know more than you: Pension fund managers don’t put more than 10 percent of their portfolios into any single stock, no matter how impressive its prospects look. Mutual fund managers often won’t exceed 5 percent, even with the stocks they most adore.

If you have a 401(k) and have loaded it up with your company stock, see whether you can sell some of the shares and move your money into diversified mutual funds, using the asset allocation models I have provided. If you can’t sell the stock, stop buying it. And put all new money into diversified stock funds.

As a novice investor, you should also avoid buying individual stocks in your IRA—that is, unless you will devote the hundreds of hours it takes to study them and make sure they remain growing, profitable businesses. Only about 30 percent of professional stock pickers do well enough to beat the stock market. So why do you think that, acting on a hot tip, you are going to do any better?