6. Why the Stock Market Isn’t a Roulette Wheel

Before I help you invest your money, I have to talk about a casino billboard I saw over a busy Minneapolis freeway. It was aimed straight for the ordinary American’s underbelly, with giant words asking passing motorists, “Does your 401(k) need some more Ks?”

The obvious solution posed by the billboard, of course, was to stop worrying about your meager little retirement fund and instead head for the casino, win, and then fill that 401(k) to the brim. No fuss, no muss—voilà, instant retirement!

Too bad it doesn’t work.

As much as we savor the fantasy of instant riches, we know that if we spend $1 at the casino, we might get $1 worth of fun and maybe even a few bucks, but no Ks for the retirement account. The trouble is that we aren’t sure what the alternative might be to build up those Ks by the time we need them.

For most Americans, investing in stocks, bonds, or mutual funds is a treacherous experience that doesn’t make sense and doesn’t feel much different than tossing some coins into a slot machine or choosing between red and black on the roulette wheel.

At work, employees are given a bizarre-sounding list of mutual funds for their 401(k), and somehow each person is supposed to make sense of the gobbledygook descriptions. Sometimes the employer brings in an investment expert who yaks for an hour in a foreign language and shows a befuddled audience some pie charts. At the end, the strange mutual fund words are just as confusing. So perplexed workers eye their list of mutual funds the way they would a roulette wheel and select one or a few. Then they spin the wheel and hope luck is on their side.

Too often black turns up when they cast their lot with red. So they lose money and decide to spin again. They ask people who know as little as they do how to win. And when they follow the leader and choose black for the next spin, the stars have realigned, and the investor loses yet again. Only this time, retirement is months closer than the last time Lady Luck failed to pay their 401(k) a visit.

The entire process seems like a mystery fraught with danger. And so some people joke helplessly that their 401(k) has turned into a 201(k)—in other words, cut in half. And then they naively move on to repeat the same mistakes with their retirement funds that decimated them in the past.

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Investing is very different from gambling. And the stakes are high. Blowing $100 at a casino is entertainment. But if a 25-year-old blows $100 in his retirement account, he will be sacrificing about $4,500 by the time he retires. That’s right, just a $100 flop is likely to cost $4,500 about 40 years later because of the power of compounding.

And it gets a lot worse if the individual inadvertently makes a habit of blowing $100 each year. If a 25-year-old destroys just $100 a year every year through ill-informed gambling moves in a retirement account, that’s potentially a loss of $53,000 from his nest egg. Again, the power of compounding magnifies the impact of a $100 annual mistake repeated for 40 years.

So eyeing your list of 401(k) funds and then throwing up your hands in frustration and deciding to just spin the roulette wheel is idiotic. If I told you today that it wouldn’t hurt you to throw $4,500 or $53,000 into the trash over the next 40 years, you’d look at me like I was crazy.

If you really invest money instead of gambling with your IRA or 401(k), you will be doing yourself a huge favor. You will give yourself a chance to make every $100 work for you instead of having to dig deeper into your pocket for another $100 to make up for the messes you have already caused.

If you have been investing in your retirement account for some time and have no idea why the money just sits there gathering dust or evaporates shortly after you’ve poured your cash into the account, you owe it to yourself to understand the harm you are causing yourself so that you can easily fix it.

You don’t have to know math. You don’t have to know how to pick a stock. You don’t have to understand the Federal Reserve’s tinkering with interest rates. And you don’t have to understand the chatter on TV investing shows. But you must know one important fundamental point that is yanking at your money at all times when it’s in stock mutual funds in your 401(k) or IRA: The stock market, and pieces of the stock market, move in cycles.

Taking Control of Cycles

Those cycles are what have been bashing your savings. And they can be cruel if you don’t understand them. They are why your mutual funds shock you and hurt you. They are why the mutual funds you might have loved in the 1990s turned into the mutual funds you hated in the 2000s. They are why your winners turn into losers and why, long after you have dumped a loser in disgust, it suddenly looks like a keeper again. It could be why you figure luck is rarely on your side when it comes to investing.

Cycles are inevitable. You cannot stop them, but you can tame their impact on your money. I’m not going to get technical on you now. But I want you to know that cycles will hurt you much less if you come to expect them the same way you expect the seasons of the year to change. Just as I can assure you that the leaves on trees will change as summer gives way to autumn and then winter, I can guarantee you that, no matter what is happening to your money in stock mutual funds now, it, too, is destined to morph as it goes into a new part of a cycle. If you have a winning fund, it will turn into a loser. If you have a loser, it will at least become more of a winner later. The perplexing question for you will be, how much later?

Often it takes so long for cycles to change that people figure it will never happen. When life is good and you are making money, it seems like it will continue forever. When conditions are awful, and you are losing money, you figure all is lost forever. That’s where people make mistakes and lose money ignorantly in the changing cycles.

And it’s not merely about stocks or mutual funds. Cycles take every conceivable investment on a ride. It happened in the early 2000s in the U.S. housing market. People assumed that homes would always be dependable investments. They were soaring in value, and people figured they could never lose on a home. They might have lost money in their 401(k) in mutual funds, but they assumed homes were different—solid, tangible, a no-brainer way to make money, much safer than the stock market.

That very thinking powered the glorious winning part of the housing cycle into a horrible downturn in the cycle that ruined lives. Millions of Americans lost the American dream and the biggest investment of their life to foreclosure.

At first, no one could imagine a downside in the cycle. People were blinded by the gains everyone was making on homes. There was a euphoria in the air and an urgency to buy homes. Regular people were buying them and selling them for thousands more in a short period of time. TV was full of shows about fixing homes, flipping homes, and getting rich in the process.

Americans bought homes at exorbitant prices, figuring they’d better move fast because homes would continually move up in price. They stretched to buy homes they couldn’t afford, thinking their home would be an investment that would always appreciate in value.

Then the crash came, and suddenly homes weren’t selling, mortgage payments were due, and people couldn’t afford to make payments they owed their banks. And because their homes had lost a third or more of their value, people couldn’t even sell them for enough money to pay back the bank. Homes had gone from being no-brainer investments to being agonizing traps.

Instead of wanting to buy homes, the mentality changed. Millions wanted to be renters. After experiencing the downturn in a cycle, many came to the conclusion that a home would be a dangerous investment.

Someday, as memories of the housing crisis fade, the cycle will turn again and people will push financially to buy homes once more. There will probably come a time when people will figure again that prices will always go up. But the plunge has left millions wary, and the downside of a cycle always does.

The lesson should not be that homes are losers rather than winners. Instead, it should be that people must be alert to cycles and be cautious about depending too much on a single investment—especially when there’s a mania around it and people assume that it’s a no-brainer money maker. It doesn’t matter whether the investment is a home, gold, stocks, or bonds. Cycles always apply. An overdose at the wrong time can be poison, and a taste early in a cycle can be delicious.

In stock market cycles, the stock market as a whole, or certain types of stocks or mutual funds, might look boring or even downright scary at the point in the cycle when people have lost interest or fled from the investments. Then, after some time has passed, the once-ugly investments start looking better and better. They become increasingly popular with investors, eventually seeming like the hottest, smartest investment anyone could buy. This is usually when ordinary investors pile in, thinking the hot investments are a no-brainer that will make people rich forever.

But with more time, the entire group of hot stocks cools off—maybe because business conditions change or maybe because smart investors decide the stocks became so expensive that they are no longer a good deal. The shrewd pros look for a better investment—something cheaper, with more chance to take off in the next phase of the cycle. They sell the once-hot investments, and suddenly the ordinary guy is holding on to a stock mutual fund wondering what in the world happened to it. His beautiful investment of yesterday has turned into an ugly money loser and is turning uglier with each passing day, seemingly for no good reason.

About 40 different varieties of mutual funds exist, and each type behaves differently during specific times in each cycle. Funds are designed that way on purpose so that investors can buy a variety and be prepared for anything. Yet given the funds you have selected, at any moment in time, you might feel brilliant or like a supreme idiot. If you have a mixture of funds, you will always like one more than the other, and as the cycle changes, your favorites will always be alternating.

The 1990s: From Stock Lovefest to Disaster

Let me illustrate what I mean by stock market cycles. I want to take you back to the end of the 1990s, one of the most vivid examples of a dramatic change in cycles since the Great Depression.

The end of the 1990s was a period of euphoria for the ordinary investor. People could throw a few bucks into a 401(k) or an IRA and make mounds of money almost overnight. Peering into a 401(k) account was pure joy. Many Americans made a hobby of treating themselves to the pleasure at their computers every day. Most didn’t realize it at the time, but they were simply riding a cycle up—a cycle that was bound to move from hot to cold, destroying trillions of dollars in the process.

In polls, individual investors naively said they thought the good times would last. They were expecting to keep making 20 percent returns on their money every year, even though Wall Street’s old-timers knew that the 1990s were extraordinary and that 10 percent returns in the stock market are the average. Even some investing professionals who should have known better were mesmerized by the moment, leading clients to destruction. They thought the economy and stocks were in a new era when old rules about cycles no longer would apply.

Investing magazines had covers posing the question “Are You Rich Yet?” CNBC’s constant stock market news was on TVs everywhere, from golf courses to Burger Kings. Giddy with their newfound wealth, people borrowed money on their homes so that they could invest in the most dangerous stocks. Many who had never analyzed a stock in their life quit their jobs to trade stocks at home computers. The mood was like the Roaring Twenties all over again—you couldn’t lose in the stock market.

At the time, John Brennan, the chairman of a mutual fund company named Vanguard, discovered how far the mania had gone. He stopped in a Burger King one night after jogging, and a senior citizen recognized him from some stock market comments he’d made on TV. The man was almost trembling with excitement about the stock market and told Brennan that he, his wife, and two friends went to the Burger King every night to watch the stock market news because they didn’t have cable in their homes. And the man asked Brennan to autograph his Burger King coffee cup. That’s when Brennan was sure investors had gone crazy over the stock market and a cruel downturn was sure to come.

Readers of my column would call me at my newspaper office to giggle about the stocks they’d bought that had doubled or tripled in value in a few weeks. Ordinary people who told me they once begrudged the rich were calling me to get information about tax shelters because they’d made so much money.

People who knew nothing about picking stocks felt like geniuses when they selected stocks such as Cisco, even though they had no idea what technological gizmos these companies produced or what would make customers want to buy them. They didn’t realize until it was too late that they’d paid about 10 times more for many technology stocks than they should have, and that ultimately set them up to lose almost everything when the game ended. Technology stocks as a group crashed about 70 percent, and many beloved Internet companies went bankrupt, leaving the stocks worthless.

But before the crash, there was one investing game in town: Buy either individual technology company stocks or mutual funds that supersized their exposure to technology stocks. Anyone who had those investments won and felt like smart investors—that is, until summer turned into autumn and, ultimately, a 2-year piercing-cold winter took hold.

Everyone Played the Game

You might not have realized any of this in the late 1990s. You might not have even imagined that you were a part of it—riding a cycle and speculating on insanely priced technology stocks. But if you had money in a 401(k), an IRA, or any mutual funds and liked the way they were behaving, you were probably part of the mania. Unbeknownst to you, the money you were making was coming from gigantic bets on technology stocks by the people who were running your mutual funds.

Amid such merriment, being cautious was the ultimate sin for a mutual fund manager. Individual investors had no patience for mutual funds that were climbing 10 percent a year while their workmate or neighbor was making 25 or 50 percent, or even more, in funds brimming with technology stocks. In 1999, the funds that invested in only technology stocks climbed an average of 134 percent—probably a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence that should have warned investors that trouble was on its way and that the cycle would have to change.

Some of the nation’s most renowned professional investors who shunned technology stocks and respected the precepts of good investing (in other words, to buy only cheap stocks) paid a dear price: Their clients resented cautious investments and abandoned the thoughtful professionals so that they could give their money instead to flashy, young upstarts caught up in the tech craze.

At the time, long-time investment pro Al Harrison, of Alliance Capital, spoke at a luncheon of other investment professionals and complained that young investment managers in his office were admonishing him for his cautious approach to hot stocks, saying, “Get with it, Granddad.” A few years later, his fund got with it too much and was almost decimated with Enron stock.

In the midst of the hot cycle, individuals who bought anything other than technology felt like jerks. Investments in companies that made machines, produced oil, sold food, or did virtually anything that wasn’t technology related couldn’t measure up. They were the ignored orphans of the stock market. Funds that invested in gold and real estate went out of business because investors wanted nothing to do with them; then five years later, as the cycle changed, investors couldn’t get enough gold or real estate.

A bond, too, was nothing but a four-letter word. After all, why would people buy such a lethargic safe investment when they could double or triple their money overnight with hot technology stocks and mutual funds full of tech?

Everyone was caught up in the mania, novices and professionals alike. I went to an investors’ conference for pension fund managers back then, and the presentation on bonds drew fewer than 20 people into a giant hotel ballroom. The sessions on technology stocks had standing room only in rooms that could accommodate hundreds.

The ordinary guy unknowingly bought all he could through funds operated by companies like Janus, thinking that the managers were brilliant. But Janus funds were simply riding a hot cycle for technology stocks. In 1999, the Janus Twenty grew investors’ money about 65 percent by sinking large sums into technology stocks. During the next three years, investors didn’t know what hit them as they lost everything they’d made and then some. Before that happened, readers got angry at me when I warned them against buying too many technology stocks and mutual funds such as Janus that were supersizing exposure to those stocks. I will never forget one person who called me and stated angrily, “You are as stupid as Warren Buffett.”

Obviously, I am no Warren Buffett, one of the most renowned investors of our time. But I knew something that every ordinary investor must know: Cycles happen, moving up and down, or from hot to cold. So technology stocks couldn’t keep giving investors returns of more than 100 percent a year.

The Game’s Up

Then it happened. The cycle started to turn in March 2000, when astute investors decided the game was up. They came to the realization that they had paid way too much for technology stocks, and the stock prices wouldn’t keep going higher every day. These savvy investors started dumping the stocks. That made stock prices nose-dive. The little guy didn’t know what was happening and held on, waiting for a return of the good ol’ days. But while his 401(k) was slipping lower every day, many of the pros weren’t riding it out with the little guy. They were selling technology stocks before they’d lost fortunes and they were buying cheap stocks in many industries that had long been ignored during the tech craze.

The market was being set up for a new cycle, a healing phase that, at first, would hurt many who clung to the past: The cheap nontechnology stocks had become cheap because no one wanted them when technology investing was driving the cycle. Yet sharp professional investors who snapped up all the solid stocks people had been ignoring knew that, with time, the cycle would change and their bargain hunting would pay off.

It took longer than many expected, but eventually the cycle changed, just as it always does. The bargain stocks that no one had wanted amid the technology craze just a couple years earlier soared in price, and investors who had them in their retirement accounts made money almost overnight. Waste Management, for example, a company that deals with collecting garbage, was unpopular with investors as it dealt with lawsuits over its accounting in the late 1990s. As the cycle changed, Waste Management stock shot up 42 percent in a few months. Nabisco, another stock people had ignored in the technology craze, climbed 183 percent as the cycle changed.

Meanwhile, investors who loved Amazon, the Internet bookstore, in the hot technology stock cycle of the late 1990s lost 67 percent in just a few months in 2000 as the cycle turned cold. Investors who put $10,000 into technology mutual funds such as the Monument Digital Technology fund at the beginning of 1999 gleefully watched their money turn into $37,300 that year and then gasped when they checked their account in September 2001 and found only $4,888 remaining.

If in 2000 you were lucky enough to have a mutual fund in your 401(k) that held stocks such as Nabisco, Philip Morris, and Waste Management, you would have been feeling pretty good after technology stocks started blowing up. Mutual funds with those bargain-priced stocks in them soared over 25 percent. But if you were like the ordinary investor, you probably didn’t know what hit you. Suddenly, your hot funds of the late 1990s mysteriously turned into losers, many destroying 50 percent or more of investors’ money.

Those holding on to the past and expecting the technology cycle to continue were being slaughtered. Internet companies went bankrupt. Retirement funds bled cash. People already in retirement had to go back to work because their savings were cut in half. The overall stock market crashed because, during the mania, it had become heavily dependent on technology stocks.

Taming the Herd

All this happened because of cycles. Several economic factors cause the stock market to go from hot to cold and cold to hot over time. But simply put, a human factor plays a major role in driving cycles: Investors tend to run in herds.

Both professionals who should know better and the common investor pile into certain types of stocks that look hot. For a while, popularity alone makes stocks rise. And the managers who bought the hot stocks for mutual funds look brilliant, when all they are doing is running with the herd. At a certain point, reality catches up with people.

Stock prices ultimately are based on more than popularity: Profits are key, and if smart investors realize profits aren’t going to measure up to the prices people paid for a stock, they dump the stock, the stock price falls, and people lose money.

To say it another way, when investors look out from the herd on some level-headed day and see that the herd is crazed and corporate profits can’t possibly live up to investors’ expectations, the herd panics and starts stampeding to dump stocks.

The old cycle cools, and ordinary investors get hurt. They hold on to their old stocks and mutual funds, waiting for them to come back. As months pass, the statements from their 401(k) and IRA look uglier. Finally the little guy says, “I’ve got to stop the hemorrhaging, or I’ll have no retirement left.”

He sells the ugliest investments at their darkest hour and then puts the money into something else. The trouble is that if he turns to another investment that looks hot, perhaps the mutual fund in his 401(k) list that has made the most money in the past year, he is likely close to the top of a new cycle.

Unknowingly, he is positioning his money to get clobbered again as soon as the cycle for that new mutual fund cools. And when that ordinary investor’s 401(k) bleeds cash, the poor guy chalks up the entire fiasco to bad luck. The trouble is, it’s not luck at all—it’s being naive about cycles. It’s about forgetting the oft-repeated precept of investing: “Buy low; sell high.”

It’s managing a 401(k) like playing the roulette wheel, but there’s a better way.

What to Expect from the Stock Market

With the realization that cycles occur in the market, you might come to the conclusion that you will stay out of harm’s way by avoiding stocks or any mutual fund that holds stocks.

That’s the conclusion that almost half of 18- to 30-year-olds reached in 2011 after watching the devastation in the stock market following the housing crash. Stocks fell 57 percent between late 2007 and early 2009 as banks and the economy were poisoned by mortgage-related blunders.

It was the worst market crash since the Great Depression. Twenty-something-year-olds were horrified as one in four lost jobs and then watched their tiny 401(k) savings evaporate while their parents lost giant portions of lifetime savings as retirement age was drawing near. In a survey by MFS Investment Management, 40 percent of people under 30 said, “I will never feel comfortable investing in the stock market.” Although the attitude seems reasonable after the shock of one of the worst recessions in U.S. history, avoiding stocks entirely is typically a mistake.

I do not suggest shunning stocks when you have years to go before retiring. In fact, most financial advisers think that even people late in retirement should have a small portion of their savings in the stock market. Notice that I said “small.” The amount of money you hold in stocks is key, which I explain in Chapter 11, “Do This.”

Perhaps if you were a multimillionaire, you could stay out of the stock market throughout your life and be fine. You could put all your savings into ultrasafe government bonds and earn a little interest on your money, and because you would have so much money in the first place, a tiny “return”— or earnings—on that money might be adequate to provide a decent lifestyle for all the days of your life.

But most Americans can’t afford to rely exclusively on ultrasafe investments such as bonds or CDs. They paid only 2 percent interest as the United States was recovering from the 2008 financial crisis. Individuals need to have a sizable portion of their retirement savings invested in the stock market to earn enough to live on later in retirement.

Although bonds were a cozy security blanket for investors throughout the horrible decade that started with the technology stock bubble crash and ended with the housing financial crisis, bonds typically pay investors only about half as much as stocks.

In the unusual decade that started in 2000, investors holding long-term U.S. government Treasury bonds earned an average of 7.7 percent a year, while stocks behaved horribly and averaged a loss of 0.9 percent a year.

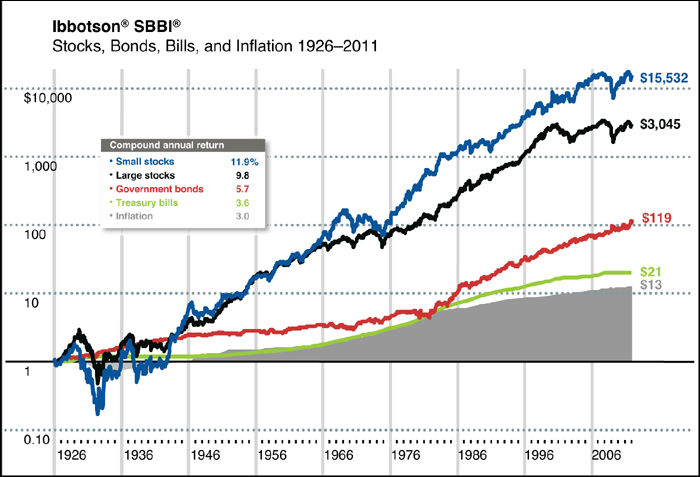

But during the past 86 years, from the end of 1925 to the end of 2011, the stock market was much more benevolent than bonds. Despite getting annihilated in stocks during the Great Depression, the recent housing-related crash, and other horrifying periods, the stock market has given investors an average annual gain of 9.8 percent over the 86-year period, according to Morningstar’s Ibbotson research. Long-term U.S. Treasury bonds haven’t come close. They have provided just 5.7 percent a year on average, and gains from intermediate-term Treasuries have been only 5.4 percent.

Stocks win because good times in the stock market have outweighed the bad over many, many years. Take a look at it in money: A person who put $1 into the stock market at the end of 1925 would have had $3,045 86 years later at the end of 2011, according to Ibbotson. But if that person had put the same $1 into long-term, safe U.S. government bonds for the same 86 years, he would have had only $119 (see Figure 6.1).

Making about $3,045 with a $1 investment might seem shocking to you if you recall some of the terrifying times in the stock market. For example, Ibbotson’s numbers include the Great Depression in the 1930s, a period when an investor would have lost 86 percent of the money invested in the stock market. It also includes an awful period in 1973–1974 when stocks fell 48 percent. Most recently, there was the terrifying period between 2000 and 2002, when common folks quaked as their stock market investments fell 49 percent amid an end to the technology stock craze, terrorist attacks, a recession, scandals in corporations such as Enron and WorldCom, and preparations for war in Iraq. Then came the financial crisis of late 2007 to early 2009, when the stock market plunged 57 percent as investors worldwide worried that the entire globe would go into a depression.

Source: Ibbotson Associates, a Morningstar, Inc., company

Figure 6.1. If you had invested a dollar at the end of 1925, this is how it would have grown over 86 years in various types of investments.

Despite all those truly horrifying cycles, $1 in 1925 still turned into about $3,045. And although no one can predict exactly what stocks will do in the future, analysts see no reason why the U.S. stock market shouldn’t continue to rise in the future—because it is based on a growing U.S. economy. Simply put, when you invest in the overall stock market through the types of funds I describe in the chapters ahead, you are investing in the overall U.S. economy.

Or as one investment manager once said to me, “The economy goes through recessions. Sometimes individual companies go bankrupt. But if a person contemplates his future and presumes that most Americans will go to jobs each day, and that they will eat dinner, buy clothes for school, drive to friends’ homes, and go shopping at supermarkets and shopping malls, that shows an inherent belief in the U.S. economy. That belief should also foster confidence in the stock market’s ability to grow.” Then he added, “If the person doesn’t think anyone is going to have a job and the world as we know it is going to come to an end, his problems are worse than worrying about the stock market. So who cares?”

Stocks Provide Risks and Rewards

I don’t mean to make light of the possibility of losing money in the stock market or the fact that the United States has some fundamental economic problems that it must address. As many investors learned in 2000–2002 and then again in 2007 through early 2009, the threat is real. But typically people incur brutal lifelong losses only when they invest money for short periods of time, panic when conditions turn ugly, and foolishly withdraw all their money without realizing that, with time, the cycle will turn.

For example, if a person had $100,000 in a stock mutual fund in a 401(k) just before the housing bust set off the crash in the stock market in October 2007, the individual might have been horrified to see only $43,000 of his money left at the scariest point in March 2009. The stock market would have destroyed $57,000 he once thought was his to keep. But the destruction at that point was on paper, based on a moment in time, and recorded in the records he received from the firm doing the accounting for his 401(k).

He would have made the destruction real and lasting if, at that dark hour for the stock market, he awoke in a sweat one night and said to himself, “I can’t take this any longer—pretty soon I’ll have nothing left for retirement.” If he moved everything the next day to the safety of a money market fund in his 401(k), he would have felt safe but actually would have positioned himself for real harm. Over the past few years, his money would have earned less than 2 percent. At that rate, even 40 years later, he would not have been able to get back to even with his original $100,000 investment. The $43,000 he rescued from the stock market’s destruction would have become only about $95,000 after waiting 40 years.

But if instead he had been able to fight off his fear when the stock market was ravaging his savings in 2009, and he left his $43,000 sitting in the stock market fund in his 401(k), after about three years, he would have been almost back to even. His $43,000 would have become about $98,000. That’s a healing number, especially compared to the wreckage people cemented into their 401(k)s when they fled.

The investor who was scared but clenched his teeth and held on to the mixture of reliable mutual funds I describe in the next chapters gained back everything lost and then some. If he kept adding money during the scary period, his money grew throughout the upward trend in the cycle, and he’s well beyond where he was before his friends fled in a panic.

Of course, it’s always easier to say what you should have done with your money in retrospect. At the truly dark hour for the stock market in March 2009, no one knew that the cycle was going to turn better soon. During every low point in the market, there is never a clear signal that the worst has occurred and investors will stop losing money and start making it again.

In fact, most of the market analysts who were studying the economy in early 2009 continued to see a frightful future ahead. That’s typical. Academic studies have shown that humans are very bad at seeing the future. They tend to expect the recent trend to continue. So when conditions have been bad, they expect more struggle ahead. And when the recent past has been delightful, they expect that to continue, too.

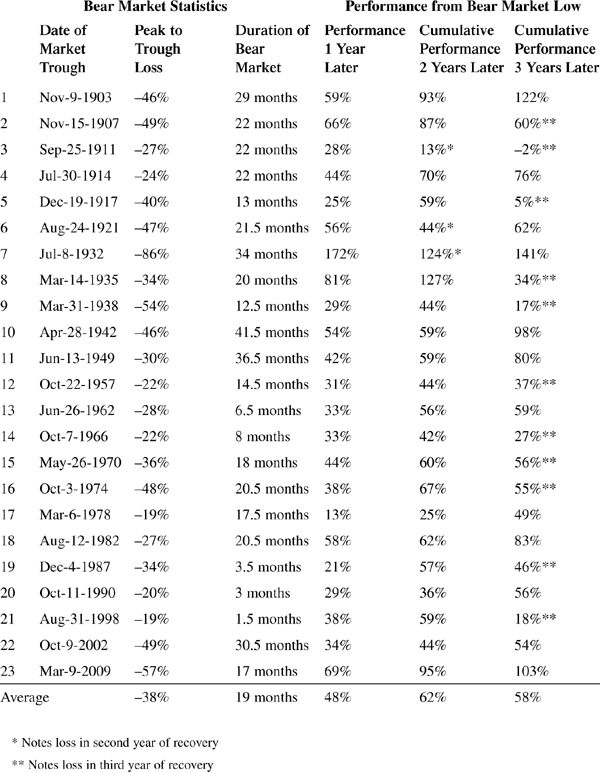

So what’s a person to do with a 401(k) or IRA? Professionals use history as their guide. They show clients the way stocks have climbed over many years and try to prevent nervous investors from fleeing solid stock mutual funds amid panics. History doesn’t provide guarantees or tell you when the good times will return, but it has shown repeatedly that changing cycles always repair the damage that has occurred if investors give the market enough time to move back into an up cycle. Because the U.S. economy continues to grow, there are rough periods when businesses and investors lose money, but the long-term trend is for the stock market to continually recover from downturns and keep climbing (see Table 6.1 for how long bear markets, or severe market downturns, have lasted and how the market recovered).

Table 6.1. Bear Markets Throughout History

Source: The Leuthold Group

Bear Markets Maul Investors

During bear markets, or periods when the market drops at least 20 percent, it’s natural for investors to get nervous while the bear mauls their savings. In the midst of the downturns, people never know when healing will occur or when they might get back what they’ve lost.

Yet The Leuthold Group found that, during the many different bear markets that have happened since 1900, the median time it took for investors to recover the money they lost was two years and three months. In half the downturns, they had to wait longer.

Still, even after the worst periods in market history, investors did recover. That’s what you must consider as an investor, or you will be doing yourself a disservice. Even after the Great Depression, and losing 86 percent of their money in the stock market, people came out fine if they had time to wait for a recovery. The crash would have been brutal for people who needed to retire soon, but not others. See what would have actually happened to people of various ages who invested $10,000 just before the 1929 stock market crash.

If a 55-year-old had $10,000 saved for retirement before the market crash in 1929, a full 10 years later, at age 65, that person would have continued feeling the pain, with only $6,000 left for retirement. But a 45-year-old in 1929 would have recovered in plenty of time for retirement. By age 65, she would have had about $14,500, despite the destruction the depression initially imposed on her $10,000. Younger people would have fared far better, demonstrating that time is on the young investor’s side. A 35-year-old who invested $10,000 just before the crash in 1929 would have seen his $10,000 become about $95,100 by retirement. A 25-year-old would have been unscathed: She would have retired with $210,300. That’s right, despite the most devastating loss in history, with $10,000 at first sinking to nearly nothing, the 25-year-old eventually ended up with more than $210,300.

Since the Great Depression, the longest it has taken Americans to recover from a bear market has been 7½ years. That long wait followed a 48 percent loss in 1973–1974. Yet people who went through the pain ended up with a delightful surprise afterward. Over the next 20 years, they averaged about a 16 percent annual return in the market.

Novices Choosing Stocks Are Gamblers

Of course, the pain in bear markets is worse if investors select certain stocks or mutual funds. For example, in the early 1970s, if you had put all your retirement savings into 50 of the most beloved stocks of the day—including Avon, Xerox, and Polaroid—you would have crashed so hard that it would have taken you 10½ years to recover your money. And the pain would have been particularly difficult to stomach, given the assumptions investors had made just before they took a thrashing.

Back in the early 1970s, when investors were loading up on those so-called “nifty fifty stocks” such as Avon, there was an assumption that the stocks were so strong investors couldn’t miss on them. They were supposed to be the stocks people could buy at any price and make money for the rest of their lives. Those promises, like all hype in the market over the years, turned out to be false. Polaroid, for example, fell 91 percent after the herd awoke to reality, and the stock price never went back to what investors had paid for it. Others, such as Coca Cola, which fell 70 percent then, regained strength and went on to delight investors who held on.

This should show you why you should not try to buy individual stocks unless you can, and will, examine a company’s financial records deeply. The stocks that fell hardest were those that were overly expensive and looked like a sure thing. Investors were sucked into the hype, falling for hot tips and promises that you couldn’t lose.

Whenever investors grab for the enticing story instead of the laborious number crunching that stock picking takes, it’s like going to the roulette wheel and putting your money on red. Luck might be on your side, but you will need luck. You are not investing; you are gambling.

Likewise, during the 2000s, many of the dream Internet stocks of the early part of the last decade disappeared. They never had a chance, despite the creative ideas that people thought couldn’t fail. And the hurt has continued. Many of the mutual funds that invested in only technology stocks never recovered. They lost 70 to 90 percent initially, and 10 years later, investors were far from getting back to even. For the span of an entire decade, technology stocks remained down about 50 percent.

In other words, if a person had invested $10,000 in technology stocks at the point of the highest euphoria at the end of 1999, that individual would have had stocks worth just $5,000 10 years later. In fact, in March 2012, a full 12 years after that initial $10,000 investment, only $6,800 in value remained. That was better than the $3,500 in spring 2006, but a huge disappointment nevertheless on a $10,000 initial investment.

Both the 2000s and the 1970s delivered a harsh but important lesson for novice investors: A company might be popular with investors, and its product might be enchanting, but that doesn’t mean that the company will survive or that the current stock price is a fair one. And if investors awaken one day and discover that the price is too high, you will get crushed if you hold on as the herd stampedes.

Getting excited about a product or a technology is not enough to carry a stock. The management in that company must also know how to raise enough money, produce a product efficiently, position it so that people will buy it, compete effectively against the competition, and survive recessions. People who can’t or won’t analyze corporate financial statements will get hurt if they buy stocks based on a tip or a gut feeling.

But you don’t have to put yourself in this position. If you buy solid mutual funds thoughtfully, you won’t need to analyze companies or do math, and you will insulate yourself somewhat from the brutality of cycles. I tell you how you can do this very simply in the following chapters. But first, a quick note about time.

Making Money Takes Time

Because cycles arrive unexpectedly in the stock market, you can never put money into any stock investment, whether it’s an individual stock or a mutual fund, and assume that you will make money in the next months or even the next couple years.

Generally, there is a rule of thumb about the stock market: Don’t put any money that you will need within five years into the market. The timing is based on the bear market research I mentioned previously. We know that cycles can and will happen, but if you look at history, investors who have been willing to sit tight and weather the downturns have generally come out fine if they could give it at least five years. Of course, after the Depression, it took more than 13 years, which is a sobering fact that cautious people might want to respect.

Still, if you want to live within the rule of thumb and are saving money for a down payment on a house, you wouldn’t put any of that money into the stock market if you plan to buy a house within five years. If your child is going to start college in four years, you wouldn’t expose money needed for the first couple of years of college to stock mutual funds.

On the other hand, if you are four years away from retirement, you can have some money in the stock market because you won’t need all of it the first year. On the day you retire, you will still be investing money for 20 or 30 more years, so you can afford to have perhaps 40 to 60 percent of your money in the stock market at first and then cut it back toward 20 or 30 percent as the years go by. (This is something to discuss with a reputable certified financial planner when you are about five to 10 years from retirement.)

For now, I just want you to recognize the risk of the stock market, but not to fear it when handled wisely. Rushing into the stock market with money you will need soon is foolish. Buying an individual stock on a tip is idiotic. But avoiding the full stock market is equally foolish when you have savings that must grow during the next 20, 30, or 40 years.

Again, history helps to lay the groundwork for thinking. Although the chances of losing money in the stock market are great over a 1-year period, and possible in a 5-year period, when you move to a 10-year period, investors have lost money only twice—between 1929 and 1938, which was the Depression, and between 2000 and 2009. Investors have never lost money over 15 years or longer, according to Ibbotson research.

When thinking about risks, remember that stocks are definitely dangerous if you rely too heavily on them or cut yourself short on time. You take on tremendous risks if you try to pick them yourself by running with the herd instead of doing serious research on their profit potential.

But another risk is critically important when saving for retirement: the risk of running out of money when you are 70 or 80 and cannot go back to work. To prevent that risk, you must respect the stock market and use it to your advantage in the simple and effective ways I explain next.