14. Simple Does It: No-Brainer Investing with Target-Date Funds

Now for the easiest choice of all. I mean easy—as easy as putting money into a typical savings account at a bank, only with a much better chance that you will be able to travel and go out to dinner once in a while when you retire.

The mutual fund industry has caught on that people are busy and overwhelmed by the strange words that are thrown at them. So the industry has created a new type of fund that could have been named “mutual funds for dummies” or “mutual funds for couch potatoes” or “mutual funds for nervous Nellies.”

The funds actually are called target-date funds, or sometimes life-cycle or retirement-date funds. I know I’ve just thrown another set of vocabulary words at you. But these are easy to spot and well worth it. If you peruse 401(k) choices and see a number embedded in the name of a mutual fund, you can sigh with relief. Your quest for the simple way out has been solved. Perhaps you’ll see a fund with a name like Target Retirement 2045 or Retirement 2020, or maybe your employer is holding meetings to tell you about these popular additions to 401(k) plans. If you consider retirement investing a hassle, you will never curse the process again.

You can buy one of these “couch potato mutual funds” for your 401(k) and, away from work, you can do the same in your IRA. With these funds, you can put all your retirement savings on autopilot for the rest of your working life.

If you select a target-date fund, you won’t have to worry about sorting through mutual fund names and categories such as large caps and small caps. Nor will you have to do any mixing and matching or move money between risky investments and safer investments. The fund itself will do all this for you—and not just for tomorrow, but for your entire working life.

You need to know only one thing: when you’d like to retire. That’s it. Simple. Just give the fees a once-over to make sure you aren’t paying too much, and you can be done. You won’t need any more funds beyond that one.

You might be confused now because I told you previously that you cannot rely on a single fund and you must combine many in your portfolio. However, a target-date fund is the exception because it is designed for one-stop shopping. A single target-date fund gives you large caps, small caps, and international stocks and bonds; then as you age, the fund manager tweaks the proportions so that you have what he deems appropriate for your age.

So if you are procrastinating because you are afraid of making a mistake, fear no more. This is a no-brainer.

Look for a Date

More than half of 401(k) plans now offer these investing shortcuts. If yours does, look for one detail: the number that matches the year you will retire. Let’s say you are 39 years old now and plan to retire at 67. That’s simple. You will retire in 2040. So you want investments geared to that target, the year 2040. Now all you have to do is find a target-date fund with the date 2040 on it.

Every target-date fund has a year in its name. So if you are looking through a 401(k) list and wonder how to find one, look for a name of a fund with a number somewhere in the 2000s on it. You might see several. Some might have names such as freedom or life path or milestone or retirement or strategy and an array of different dates on them.

Don’t let the variety worry you. The different dates on them are there merely because each person needs to find the fund aimed at his or her particular retirement year. And words such as life path and freedom are simply supposed to clue you in on the intent: to get your money ready for your retirement date.

If you are 40, you wouldn’t pick a fund with 2020 in its title unless you intended to retire early. If you are 40 and are planning to retire at 67, an appropriate fund would be one with 2040 in the name, getting you ready to retire in 2039. The fund dates put you close to but not exactly on your actual retirement date. Most likely, the 2025 fund would be right for someone who is 54. For someone 30, the 2050 fund would be smart, preparing the person for retirement at about age 67, or the year 2050.

If you are 25 and are nervous about investing but have a 401(k) with a fund with 2055 in its title, you can use it and probably relax from that point forward. You can also do the same with an IRA. You simply contact a firm such as Vanguard (800-997-2798), T. Rowe Price (800-638-5660), or Fidelity (800-544-8544); select a target-date fund with the number 2050 in its name; and barely give it a second thought for the rest of your working years. Tell the mutual fund firm to automatically take money out of every paycheck and put it in that one mutual fund over and over again throughout your working life.

At age 67, you should be set, even though you devoted almost no attention to your investments during three decades—that is, of course, if you saved plenty during your working years, too, and didn’t simply count on your investments to do all the heavy lifting. No fund is a miracle worker. If you are saving a pittance, a fund manager can do only so much to make it multiply. And you don’t want a fund manager to try to make up for your saving shortfalls by taking too many risks in the stock market when you are on the verge of retiring. That could mean you get slammed by a huge loss right when you need your money most.

Tweaking As You Age

Target-date funds are designed for one purpose: to grow your money effectively so you have as much as possible for a set date. You simply clue the fund manager into what he or she needs to do for you by giving the manager your target. You tell the fund manager the date you plan to retire by buying the appropriate fund, the one carrying your retirement date. Then the manager knows what combo of stocks and bonds should fit the stages of life you will go through on the way to retirement. As you age, the manager adapts the mixture each year for the rest of your working years so that it should be appropriate for your age. You will never need to buy another fund.

Your fund manager will be acquainted with academic studies that show how types of stocks and bonds work over time through different cycles. So the fund manager will buy a mixture (with market-cycle shock absorbers built into the mix) and will continually tweak the recipe for your age and the number of years to retirement. When you are young, you will have mostly stocks in your target-date mutual fund, along with maybe somewhat riskier stocks. As you enter middle age, the manager will slowly, year by year, cut back on stocks, adjusting for less risk and keeping more money in bonds and cash.

I don’t want you to think that these are magical devices that won’t lose money at times. These funds have large doses of stocks, so when the stock market goes down, you should expect to see your fund drop, too. In fact, they can plunge enough to make a person nervous at times. For example, in the 2008 financial crisis, funds intended for people in their mid-20s plunged about 39 percent because they were invested almost completely in stocks. Those for people in their mid-50s lost about 29 percent.

If your fund manager has taken the prospect of horrible market downturns seriously, you should not suffer a devastating loss when you cannot recover from it. Yet fund managers tend to have an appetite for stocks— sometimes greater than individuals have. The professionals argue that everyone needs significant exposure to stocks, or their money won’t grow enough in time for retirement. That argument is valid, but it can go too far for my taste for people relatively close to retirement.

Most funds, geared toward 50-year-olds retiring in 2030, for example, recently divided an individuals’ money 80 percent in stocks and 20 percent in bonds. This could mean that a target-date fund might be riskier than a particular person can stomach even though the fund manager considers it best for the individual’s age.

People very close to retirement in 2008 were shocked at the risks they were taking with target-date funds. The average fund, designed for people just two years away from retiring then, lost almost 25 percent.

Severe losses sent near-retirees into a panic. Many had assumed that the target-date funds guaranteed they’d have plenty of money for retirement, so they bolted out of fear and locked in sharp losses for life. As a result, they either would face very frugal living in retirement or would have to work for many years longer than expected.

So be aware: Your target-date fund is geared to getting you ready for retirement, but there are no guarantees. Nasty cycles can emerge and play havoc with your money. If you want to make sure your fund manager isn’t subjecting you to more risk than you want, look at the mixture of stocks and bonds and compare it to the portfolios I have laid out previously. Check out the portfolios under “A Reality Check for Fear,” in Chapter 11, “Do This,” to imagine worst-case scenarios and also to understand that a well-conceived mixture of stocks and bonds will recover if you can give it some time.

You don’t have to accept a target-date fund that you think is overly risky, especially if you are near retirement. Many different fund companies create these funds, and they vary widely in the risks they take with your money. For example, in 2008, when the market crash came, some target-date funds were careful with money for people planning to retire in two years. The most conservative one had just 3.6 percent invested in stock and left people unscathed amid the market carnage. The riskiest had 41 percent in stocks. People have recovered since then, which should provide some assurance if a market crash happens close to your retirement. Yet angst matters, too. And in 2008, people planning to retire in two years didn’t know whether they’d end up with the money they would need.

Realize that much disagreement circulates among professionals about what an ideal portfolio is at certain ages. For example, among 2025 funds geared toward someone around 55, some target date funds had as little as 38 percent invested in stocks in 2012; others had as much as 86 percent.

If you are in your 20s and 30s, and have been convinced that stocks recover over time in cycles, you can go along with the target date fund in your 401(k) that puts almost all your money into the stock market. Little controversy exists about the wisdom of heavy stock exposure for people in their 20s and 30s. But there is significant debate about what’s appropriate for people in their 50s and 60s.

Some critics have asked the government to put limits on stock exposure, but the government has left it up to you to know what’s in your fund and to decide whether the mixture feels right to you.

Of course, you don’t need a target-date fund to get ready for retirement. If you happen to have a 401(k) with a fund that you don’t like, you can create your own mixture of individual funds, as I laid out in previous chapters. In fact, if you pick individual funds, and in particular index funds, you will probably keep your fees lower and make more money over time than if you use target-date funds; some target-date funds charge relatively high fees.

But if you are reluctant to give your money the attention I’ve described in the preceding chapters, a target-date fund is an easy approach that will slide your money slowly but regularly out of stocks and into bonds as your retirement draws nearer.

Say that you are 50 and you buy the Wells Fargo Advantage DJ Target 2030 (WFETX). In that single fund, you have the mixture that’s appropriate for a person your age on the way to retirement. In mid-2012, you would have had about 46 percent of your money in U.S. stocks, 21.5 percent in international stocks, 25.8 percent in bonds, and 6 percent in cash. But this is not a static mixture. It’s designed only for a 50-year-old who won’t panic if the stock market acts up and yet isn’t willing to go overboard with stocks. It’s called “moderate” for a person who doesn’t have a stomach for significant risk but knows it’s wise to grow money in stocks. Each year, the fund manager makes changes based on your age, keeping your money safer as time goes on.

A look at another Wells Fargo Advantage Target DJ fund illustrates what happens as the next five years pass. Consider the Wells Fargo Advantage Target DJ 2025, aimed at people around 55 and retiring in about 10 years. A person getting close to retiring can’t afford to lose significant amounts of money. So that portfolio is a lot safer than one for a younger person. It would look like this: about 38.2 percent in U.S. stocks, 18 percent in foreign stocks, 37.4 percent in bonds, and 6 percent in cash.

One last comparison will help you understand the shifts. Let’s now go to the 29-year-old who would buy the Wells Fargo Advantage Target DJ 2050. That person is trying to grow his or her money as much as possible and can take risks because there is plenty of time to regain ground if the stock market swoons for a while. So here’s the portfolio: 59.4 percent in U.S. stocks, 28 percent in foreign stocks, 6.5 percent in bonds, and 6 percent in cash.

If you look up any target-date fund on the internet, you will see a graph of what’s called the glide path. It’s supposed to show you what happens to your money as you age. The fund manager “glides” you out of stocks on a slow path and into increasing amounts of bonds. So in the case of the Wells Fargo funds, you start with roughly 87 percent of your money in stocks at age 29 or 30 and end up with about 56 percent in stocks as you approach age 60. Wells Fargo is among the most conservative companies. T. Rowe Price, on the other hand, takes the position that when people retire, they still have 30 years of investing ahead of them. So by age 55, T. Rowe Price’s retirement-date fund would still have about 78 percent of your money invested in stocks.

That’s a lot of stock exposure and fine if you share T. Rowe Price’s perspective. It’s true that at 55, you are investing for the next 30 or 40 years— leaving time to recover from a stock market crash. But at 55 some people start worrying about what they will have at 65, and they eye their retirement savings anxiously each day to assure themselves they will be okay when they retire. If you are among this group, having 78 percent of your money invested in stocks is probably too risky to stomach.

What to Do When 401(k) Funds Lack Target-Date Funds

If you have a 401(k) and your employer doesn’t offer one of these no-brainer funds, get your coworkers together and ask the person in charge of benefits to add one. Encourage the benefits staffer to select low-cost target-date funds such as those offered by Vanguard—but don’t be alarmed if you see a target-date fund with a less-well-known name. Plenty of fine firms are designing target-date funds, and some employers offer no-name funds created specifically for their employees. Just make sure they aren’t overly expensive, with fees over the average of 0.61 percent. If they are closer to 0.30 percent, that is better.

If you don’t have a target-date fund now, you are likely to have one in the near future. They are popular among employers and with individuals who don’t want to bother with money decisions. They are also popular with the U.S. government, which has told employers to automatically put their employees into these funds. The government wants to make sure people are getting ready financially for retirement.

Vanguard has estimated that, by 2016, 75 percent of people enrolled in its 401(k)s plans will be in target-date funds. If you don’t have target-date funds at work and you can’t nudge your employer to use them, don’t worry. Target-date funds can help you even if you never invest in one. They can serve as models for asset allocation. You could go to the Internet, look up a target-date retirement fund for your age, and use it as a guide. In other words, if you are 25 and don’t know what to do with the small selection of funds an employer has given you in a 401(k) plan, just piece together the puzzle by matching your fund categories to those in a target-date fund such as T. Rowe Price’s. You will then have your asset allocation, or percentages of various funds, about right.

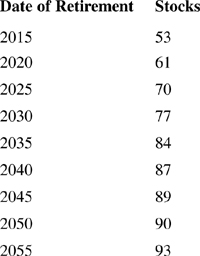

Or to decide on the basic mixture of stocks and bonds, consider the averages in target-date funds analyzed by Morningstar in 2011. Here you can see the average portion held in stocks for each retirement date. The remainder typically is mostly in bonds, although some funds have about 5 percent in cash.

How to Select a Target-Date Fund

If you get your benefits staff to listen, or if you select a target-date fund on your own for an IRA, two major issues need attention: the riskiness of the stock and bond mixtures in each fund, and the fees you have to pay for each fund.

As I explained in the previous section, fund companies don’t agree on the risks you should take in stocks and bonds at various ages. So the funds vary greatly.

If you want to know whether the fund you are being offered is excessively aggressive, compare it to the averages I just provided in the previous chart. If the fund for your retirement date in your 401(k) is taking greater risks than you think you should assume at any age, you have a simple solution. Look through your list of target-date funds at work, and pick one for someone older than you.

For example, say that you are in your 20s and would typically pick a 2055 fund. But you see that it puts 93 percent of your money in stocks, and you can’t stand the idea of such a large stock market exposure in a horrible market. Instead, you could select the fund with a 2025 date in it, a fund geared toward people in their mid-50s. In that case, only about 70 percent of your money would be in stocks, which would reduce the sting in an awful bear market.

Meanwhile, if you go shopping for a target-date fund for an IRA, you will have a wide range of target-date funds available. Then you will have to decide whether you are more worried about the shorter-term risk of losing money in a bad stock cycle or the longer-term risk of running out of money in retirement because you were too cautious with investments when young.

For a quick peek at your risks in each target-date fund you consider, look up the fund at www.morningstar.com and click on “Portfolio” to see the percentages of stocks and bonds in the funds. Then you can decide whether one feels more comfortable to you than another; perhaps also reread Chapter 9, “Know Your Mutual Fund Manager’s Job,” and consider the 2008–2009 losses and healing covered in Chapter 11.

As you consider the fees that each target-date fund charges, it might also help to review Chapter 12, “How to Pick Mutual Funds: Bargain Shop.” But in a nutshell, the fees you pay for funds can strangle your returns, even if they look like small numbers. And target-date funds can layer on relatively huge expenses that can reduce your nest egg years into the future. So look at what can happen.

Assume that you are going to retire in 2035, and you have $25,000 to invest in a target-date fund. You consider two of them: the relatively expensive Oppenheimer Transition 2030 fund and the low-cost Vanguard Target Retirement 2035. The fees don’t look so bad at first glance. Oppenheimer charges 1.25 percent of your assets (or money in the fund), and Vanguard charges 0.19 percent. But assume that the investments in both funds do equally well, climbing an average of 8 percent a year. With the cheap Vanguard fund, you will have about $237,615 after 30 years. With the more expensive Oppenheimer fund, you will have only $162,573. Why? Simply because of fees. In the Vanguard fund, you had a 5.75 percent sales change, or load, upfront and then relatively high fees. They totaled $29,658.

So with life-cycle funds, as with any other type of mutual fund, pay attention to fees in addition to the track record, or returns, over at least the past three years. Morningstar analysts suggest keeping the expense ratio under the 0.86 percent average because there are quality funds within that realm. If you buy one on your own, look to funds that charge no more than Fidelity, at 0.74 percent, or T. Rowe Price, at 0.79 percent. Vanguard is even more attractive, at 0.18 percent.

There is no reason to buy a target-date fund with a load, or a sales charge. As you probably recall from Chapter 12, loads are supposed to compensate brokers for the advice they give you. But target-date funds are no-brainer funds, so you shouldn’t need to pay a broker for assistance.

As you evaluate funds offered by the giants in the field (Fidelity, Vanguard, and T. Rowe Price), think of Vanguard as the low-cost stand-out, which takes risks in the stock market fairly close to the average. T. Rowe Price and Fidelity charge higher fees and take greater risks by holding somewhat more stock than the average.

T. Rowe Price is the best choice for investors opening an IRA with very little cash. Most funds won’t let you through the door unless you have $1,000 or more, but T. Rowe Price accepts investors with as little as $50. With that sum, however, you must be willing to add $50 a month to the fund.

If this detail makes you nuts about the choices in front of you, don’t hesitate. You can’t go wrong with any of these funds. All are set up to give you a blend of investments; they ratchet back your risks as you age so you don’t have to do the work, and they give you a chance to make a solid return. Procrastinating, however, will do you in. Skipping stock market risks altogether will do you in. Swinging for the fences with a single stock or one hot fund will almost certainly do you in, too.

Getting started is much more important than picking the perfect fund. Just keep in mind that, if you pick a target retirement fund, you don’t need any other funds. This might be confusing for you because I told you in previous chapters that you need to diversify and can’t rely on a single fund. I’m not contradicting that now, however. A target-date fund is a different animal from a simple large-cap stock fund or a small-cap stock fund. It puts everything you need into one fund, so it’s a complete diversified portfolio with an appropriate mixture of stocks and bonds. If you choose a target-date fund and even one more fund in a 401(k), you will throw off the formula, taking on either too much risk or not enough.

The same goes for your IRA. If you pick a target-date fund for it, you are done. You don’t need other funds. That’s the beauty of it.

Other Similar Choices

The easiest fund of all is the target-date fund. For the person who doesn’t want to bother with asset allocation, it would be my choice. But your 401(k) might not offer a fund with a date in the name.

Instead, you might see other so-called “life-cycle” funds. These funds do not manage your money specifically for a certain retirement date, so they aren’t quite as simple to use. But the concept is close. They require you to do a little more thinking. They ask you how much risk you are willing to take. And then they decide on a mixture of stocks and bonds based on that.

So you might see funds with names that include “life strategy” or “spectrum” or “asset manager.” When you choose one of them, you might have to decide among one that takes the most risks (“aggressive” or “growth”), one that takes fewer but still significant risks (“moderate growth”), and one that is low risk (“conservative”).

The beauty of these funds is that they take some of the asset allocation concern off your hands. But unlike target-date funds, they don’t remove the entire burden. They all buy a blend of stocks and bonds, but because they base it on risks instead of the time frame to retirement, you can’t stick with the same fund for life.

You need to sell one fund and move into another less-risky fund as you age. For example, you might start in your 20s with an aggressive approach, move to moderate growth in middle age, and become conservative during retirement.

Just don’t fall asleep at the switch with one of these funds. You’d be making a mistake to have all your money in one aggressive life-cycle fund on the eve of your retirement.

Old-Style Life-Cycle Funds

Your 401(k) might not give you a choice of a target-date or life-cycle fund because these are relatively new. Small employers might simply have a few choices that have been around for years.

But do not fear. You still might have a very easy choice.

Look at the list. If you see the word balanced, that fund will also make life easy on you. It won’t tweak your mixture of stocks and bonds on the basis of your age, but it will blend stocks and bonds for you at all times— roughly 60 percent in stocks and 40 percent in bonds.

So it might not be as aggressive as you want to be at age 25. But if you find the entire selection process overwhelming and don’t know where to start, you won’t go wrong with a balanced fund.

You can always start your 401(k) by putting all money into that one fund. It’s a classic. Then get comfortable with investing. Learn more, and then maybe get more aggressive a few months later by taking more risks with stock funds. Keep the balanced fund as a core fund, and add a little more stock to your investments with one or two more stock funds later.