Preservation

Why?

Abstract

The preservation efforts made by the government, institutions, and individuals comprise the main part of the chapter. After an overview of the preservation work in ancient China is presented, concentration is shifted to digitization technologies that have completely transformed the way that collections and services of public and academic libraries as well as archival institutions are managed and provided. I attempt to portray some unique practices in Chinese digitization and introduce several popularly used online databases that have served on providing necessary information and data to support academic research.

Keywords

Digital preservation; Digital projects; Book pavilion; Electronic resources

Many government agencies, cultural and educational institutions, corporations, and individuals take the responsibility of discovering, identifying, acquiring, processing, preserving, maintaining, and providing access to scholarly materials. With a rich history of scholarly information preservation, China has adapted various practices both in the past and present. Throughout history there have been disconnections and continuities in the book preservation tradition. To better understand the current conditions, it is helpful to start the description from the very early days.

3.1 A Historical Review

Information preservation could occur as early as the invention of the earliest forms of writing expressions. The earliest writings recognized in China, dated back to the Shang Dynasty, were divinatory inscriptions on oracle bones, primarily ox scapulae and turtle shells.1 Used for divination in the royal Shang court, characters were carved on the bones and then heated over a fire to create cracks which were interpreted to tell the future. Their discoveries in immense amounts from the capital of the Shang regime have indicated people's intent and efforts to preserve the writings, thus the imperial history. In actual fact, later historical documents did record the presence of royal historians who were responsible for cataloging and preserving the bone scripts in the Shang.

In the subsequent dynasties a special group of government officials were assigned to manage imperial documents; and whose assignments were identified as drafting and promulgating statements, collecting and selecting documentation, and providing easy access to the documentation.2 Titles of these officials and their institutional affiliations varied from time to time; so did bureaucratic rank and responsibilities of the people and size and structure of the institutions. The procedure of document preservation had been gradually systemized over time, providing crucial resources for each government to help make policies, assemble historical events, and train new generations of officials. The introduction and improvement of the moveable type printing technologies especially brought about massive advances for the preservation endeavors of ancient Chinese so that imperial (and/or government) collections could experience rapid and dramatic growths.3 It was based upon the rich collections that such famous historical series as Yongle Dadian 永乐大典 (the Yongle Encyclopedia) and Siku Quanshu 四库全书 (the Complete Library in Four Branches of Literature) were compiled in the Ming and Qing Dynasties respectively, each of which was regarded as the largest encyclopedia of the world at its time.

In the early times, imperial archives were also government collections because the entire country was considered to be the private property of the emperor. When administrative structures became increasingly sophisticated, the creation and management of book and other archival collections had also become diverse. Imperial collections 宫廷藏书 started being separated from governmental collections 官署藏书, although their uses were often interchangeable. Specifically designed buildings were constructed to store these collections, known in Chinese history as cangshu lou 藏书楼 (book pavilions).8 The design of book pavilions took into consideration fire hazards, molding damages, and termite threats, and was chosen to locate in quite places with attractive landscapes. With an ever increase in print materials, both the number and size of book pavilions expanded over time, which helped protect historical publications and advance scholarly communication. In the Qing alone, the government built seven legendary book pavilions to store Siku Quanshu, the former four pavilions in the North and the latter three in the South:

1. Wenyuan Ge 文渊阁 (1775) in the Forbidden City 故宫 in Beijing

2. Wen'yuan Ge 文源阁 (1775) in Yuanmingyuan Park 圆明园 in Beijing

3. Wenjin Ge 文津阁 (1774) in Bishu Shanzhuang 避暑山庄 in Chengde, Hebei Province

4. Wensu Ge 文溯阁 (1782) in the Palace Museum 沈阳故宫 in Shenyang, Liaoning Province

5. Wenhui Ge 文汇阁 (1780) in Daguantang 大观堂 in Yangzhou, Jiangsu Province

6. Wenzong Ge 文宗阁 (1779) in Jinshan Temple 金山寺 in Zhenjiang, Jiangsu Province

7. Wenlan Ge 文澜阁 (1782) in the West Lake 西湖 in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province

From the Han Dynasty onwards, royal families and governments followed the same book pavilion model to preserve their collections, while individuals from the Song onwards were allowed to build their own pavilions for private uses.9 The above mentioned Wenyuan Ge is one of the famous book pavilions that was built in the Ming and rebuilt in the Qing. Today's Wenyuan Ge inside the Forbidden City in Beijing is the site of the Qing's imperial library/archives, consisting of a two-story building surrounded by walls on all four sides. There is a pond with a mini bridge in the front yard and a rock garden with an evergreen forest in the back yard. The building is in the style of traditional Chinese architecture, covered by a wide variety of motifs and tiny sculptures externally and internally (Fig. 3.1). Inside the building are places for the collection of Siku Quanshu and its catalogs, a small lecture hall, and a chamber for the emperor to study and take breaks. The original handwritten copy of Siku Quanshu stored here is now preserved in the National Palace Museum in Taiwan.

The architectural style and structure of Wenyuan Ge are an imitation of Tianyi Ge 天一阁 (Fig. 3.2), a private book pavilion built in the mid-Ming which is the earliest existing pavilion today. With its size at around 280,000 square feet, the latter pavilion represents the apex of private library tradition that started as early as three thousand years ago. These costly architectures and collections could only be afforded by highly ranked government officials, wealthy individuals, and recognized scholars. It had actually set the fashion for elites to amass valuable books and create popular book pavilions in ancient China. While privately maintained, many of the private libraries were open to selected intellectuals and, therefore, had supported information preservation and scholarly creations.

Book pavilions were also maintained by temples for stacking and conserving Buddhism and Taoism documents and by shuyuans for instruction and scholarly research. In many dynasties, particularly the Tang, temple libraries formed consortia to systematically translate and interpret Buddhism collections and protect them in a cooperative manner. For shuyuan libraries, because of their connection with concurrent government libraries, documentation sharing between the two systems was rather common, and both benefited from the specialties and collection richness of the other.

The Chinese developed the earliest bibliographies in the world. The first known bibliography, Qi Lue 七略, was published about 2100 years ago in the Han that classifies books of all subjects into six groups, under each of which a total of 38 subgroups are proposed.12 This classification system was adopted in the following 300 or so years and experienced major revisions to grow into a four-categorization one 四部分类法 (Jing, Shi, Zi, and Ji) that dominated in Chinese classification until the western bibliographic structures were introduced to China in the early 20th century. Siku Quanshu is one of the classic examples of the four-categorization; and even the title of this encyclopedia itself reflects its adoption of the classification (the word Siku means four classes). Although there were variations of these classifications, namely, a seven-division and a twelve-grade, in history, it was the four-categorization that was considered to best arrange Chinese publications and had played a significant role in preserving and organizing historical Chinese documents.

3.2 Present Practice

3.2.1 Libraries

The first book pavilion, Guyue 古越藏书楼, that was designed to exclusively serve the public was founded by a government official in 1902 in Zhejiang Province.13 It adopted the concept and practice of public libraries in the West and symbolized the appearance of modern libraries in China. Guyue compiled its own bibliography for a collection of around 70,000 book volumes, which blended traditional Chinese classification system with international conventions. In the same year, an American librarian, Mary Elizabeth Wood, opened a study space at Wenhua Institute in Wuhan for students as well as the public to check out books and conduct study.14 It was the first library in China that utilized the Dewey Decimal and Library of Congress classifications to catalog book collections. Within a short period of two decades after Guyue and Wenhua were available, a group of similar, but larger public libraries emerged across the nation, including the grand opening of Hunan Library in 1904 and Peking Library in 1912.15,16 The significance of opening of these libraries is that they started offering necessary spaces for citizens who did not have access to restricted royal and private book pavilions to study. The activities of scholarly communication were eventually extended from elites to the ordinary people.

In response to the appearance and growth of public libraries, the then governments issued official rules and regulations to govern their practice and guide their development. Necessary trainings were arranged to produce competent librarians. For academic libraries that also boomed in this period of time library science graduates from overseas countries were largely employed to embrace the Western ways of library management.15 Peking University Library (PUL), as one of the earliest academic libraries, adopted the modern concept of librarianship and witnessed a speedy growth of its collections, having been able to reach around 184,000 volumes of book within twenty years since it was created in 1902. Many other types of libraries, for example, special, corporate, association, and research-oriented libraries, such as the Library of Forbidden City, were also created.

In the following decades, unfortunately, Chinese library enterprise took a rollercoaster ride due to a series of political, economic, and military incidents. Major destructive events included the second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), the Civil War between the Nationalist and Communist (1945–1949), the Anti-Rightist Campaign (1957–1959), and the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), during which time all types of collections were severely damaged and library services were substantially interrupted. By the late 1970s when China started its systematic economic reforms, the number and size of government libraries were very limited.

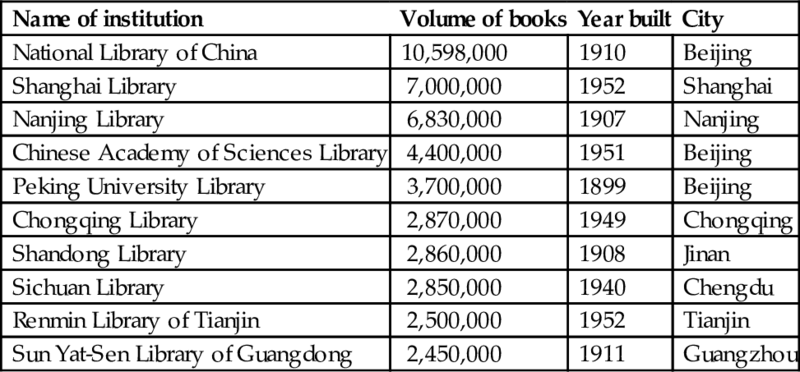

Over the past three decades, however, China's gross expenditures on R&D have consistently increased, and the government has invested extensively in public, academic and special libraries. It is not surprising to see a dramatic expansion of scholarly collections, a thrilling growth of public services, and an amazing arrival of magnificent constructions in recent years. Unlike the early times of modern library development when private libraries flourished, libraries under the Communist Party control after 1949 have been all government entities regardless of their type, size and location. Libraries have been a public enterprise. Table 3.1 lists the top ten largest libraries based upon the size of their book collections as of 2014.

Table 3.1

Top ten libraries by volume of books17

| Name of institution | Volume of books | Year built | City |

| National Library of China | 10,598,000 | 1910 | Beijing |

| Shanghai Library | 7,000,000 | 1952 | Shanghai |

| Nanjing Library | 6,830,000 | 1907 | Nanjing |

| Chinese Academy of Sciences Library | 4,400,000 | 1951 | Beijing |

| Peking University Library | 3,700,000 | 1899 | Beijing |

| Chongqing Library | 2,870,000 | 1949 | Chongqing |

| Shandong Library | 2,860,000 | 1908 | Jinan |

| Sichuan Library | 2,850,000 | 1940 | Chengdu |

| Renmin Library of Tianjin | 2,500,000 | 1952 | Tianjin |

| Sun Yat-Sen Library of Guangdong | 2,450,000 | 1911 | Guangzhou |

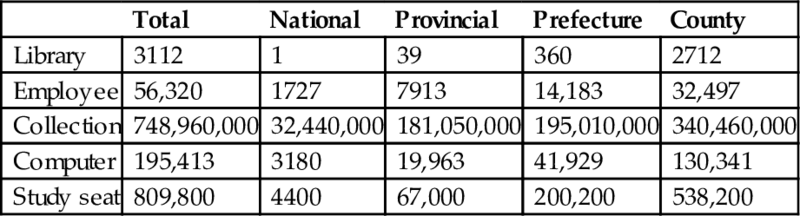

Of this list, except the research-oriented Chinese Academy of Sciences Library and PUL, all are public libraries funded directly by the central and provincial governments. To paint a larger picture of public library development, the figures in Table 3.2 provided by the National Bureau of Statistics of China tell that each city, no matter it is at the provincial level, prefecture level, or county level, has one library, because the total number of libraries roughly equal the total number of cities of all levels. Also, the scale of public libraries, by employee, collection, computer and study seat, matches the size of their cities (see Table 3.3 for library averages). China's administrative division, although it is complicated, can be simplified to central > provincial > prefecture > county, with each seat being the largest city of a division and the size of the seat being proportionally reduced along the administrative ladder. Hence, when a library located in the capital of a province has 203 employees, a county library on average only staffs 12 people; and while the former owns a total collection of 4,642,307 books, the latter has only 125,538 books.

Table 3.2

Data of public libraries as of 201318

| Total | National | Provincial | Prefecture | County | |

| Library | 3112 | 1 | 39 | 360 | 2712 |

| Employee | 56,320 | 1727 | 7913 | 14,183 | 32,497 |

| Collection | 748,960,000 | 32,440,000 | 181,050,000 | 195,010,000 | 340,460,000 |

| Computer | 195,413 | 3180 | 19,963 | 41,929 | 130,341 |

| Study seat | 809,800 | 4400 | 67,000 | 200,200 | 538,200 |

Table 3.3

Averages per library (based on Table 3.2)

| National | Provincial | Prefecture | County | |

| Employee | 1727 | 203 | 39 | 12 |

| Collection | 32,400,000 | 4,642,307 | 541,694 | 125,538 |

| Computer | 3180 | 512 | 116 | 48 |

| Study seat | 4400 | 1718 | 556 | 198 |

Considering the population density in Chinese cities, these numbers of public libraries are actually still small. According to a survey, as of the end of 2011 just over 440,000 citizens owned a library.18 Also, the geographic distribution of public libraries favors great urban regions across cities and is disproportionate within each city. Urban centers regularly receive more supports from the government than county-level cities do and, thus, are able to develop larger collections and construct more learning spaces. For example, Beijing is the location of the National Library of China as well as of a capital library system and many municipal library branches, in addition to more than a hundred academic and special libraries, while Gushi County 固始县 in central China's Henan Province only has a single library to serve a total population of around 169,000 residents.

Within each large city where multiple libraries or library branches exist, their geographic locations for serving an optimal radius of residential neighborhoods are far from ideal. This is because libraries are not the priority in most urban planning. To improve their services, many cities have constructed so-called library-ATMs in major communities in recent years for the sake of convenience to their citizens. These library machines are larger in size than regular banking ATMs and loaded with popular books or multimedia items for library card holders to automatically check out and check in. However, the self-served machines have been underused in general because of their limited number of stored items and lack of personal assistance.19 Young readers find them less attractive than what social media and the Internet have offered, while senior users are intimidated by their intricate functions.

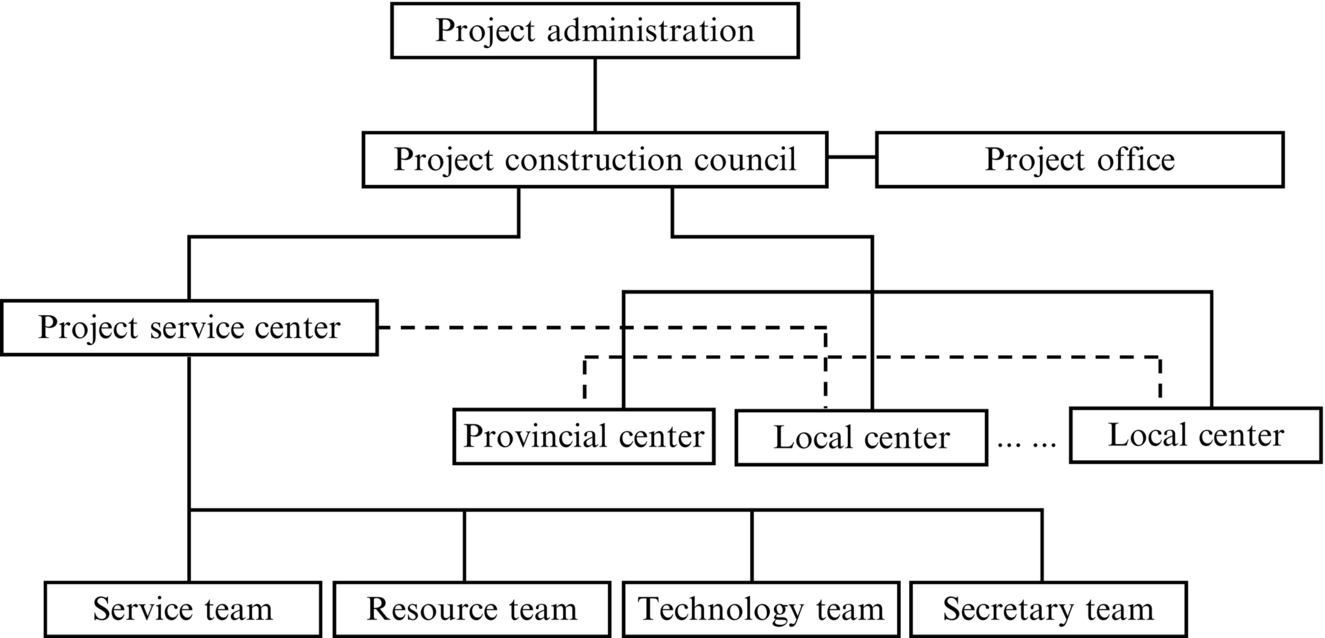

China has more than one thousand academic libraries nationwide, and this number does not include research-oriented noninstructional institutions.20 To facilitate resource sharing, the government organized the Chinese Academic Library & Information System (CALIS) to converge digital collections and library services.21,22 Started in 1998, CALIS has established a national center at Peking University and eight local centers to cover different regions of the country with a membership of more than 500 libraries. Its most recent efforts are to incorporate electronic resources into the system with scholarly materials in both Chinese and English languages. With such a resource sharing system, Chinese academic libraries have been able to fulfill their goals of serving higher-educational institutions in curriculum development, faculty research, and student learning. They have played a key role in collecting and preserving learned documentation and support scholarly communication.

3.2.1.1 Remarks

The chronological and geographic differences of library development, both academic and public, mirror concurrent economic and political conditions. Historically, libraries have had their heydays and downfalls. Although peacetime might not necessarily guarantee an expansion, battleship did bring about damages to libraries for their construction, collection, and workforce. Geographically, the presence of a community-divide and a city-divide has inevitably created an inequity of resources for libraries as well as library users. People who live in some areas of a large city are always luckier for accessing library resources than people in other areas. We anticipate changes to the inequality when digitization has become prevalent in library practice and people have been used to electronic library collections.

3.2.2 Librarianship

In order to qualify for a librarian, one will need to have received formal training in library science.27,28 The government guidelines for academic libraries published in 2015 asks for a master's or a higher degree in library science from a nationally accredited program.29,30 The guidelines even demands more than 50% of the staff in a college library to possess at least a bachelor degree. Once employed, a librarian is encouraged to take courses beyond library science unless s/he has already had a subject degree. Scholarship is amply valued and is usually measured by the number of a librarian's publications and the prestige of the publishing venues. Yet, just like many other academic organizations, libraries evaluate a librarian's scholarly achievements more on quantity than quality. As a result, it has brought in tremendous lemon articles and low-quality journals useless to the profession.

Formal library training is provided by about twenty higher-educational institutions and a few academic libraries.31 Many academic programs accommodate three specializations, namely, library science, archival studies, and information management, while some deliver training in multidisciplinary areas such as business information, bio-information, and electronic editing and publishing. Their curriculum resembles that of the Western countries, particularly the United States, including such conventional areas as public services, digital libraries, technical services, and the like.

Wuhan University has the oldest library science program and its School of Information Management is a top-ranked one in China today.32 Created in 1920 by Mary Elizabeth Wood and Samuel T.Y. Seng, this program has developed into a major academic entity that covers library science, information management science, archival and government science, digital libraries, and publishing and e-commerce. As of the early of 2016, it had 110 faculty and supporting staff, 916 undergraduate students, 522 graduate students, and 192 doctorial students. Throughout its history Wuhan University has produced hundreds of librarians who are now working in different types of library. Frequently ranked in the top ten library science programs are Peking University, Nanjing University, Nankai University, Sun Yat-Sen University 中山大学, Zhejiang University, Renmin University 人民大学, Beijing Normal University 北京师范大学, and Zhengzhou University 郑州大学. Renmin University is especially strong in the training of government information and archival science.33

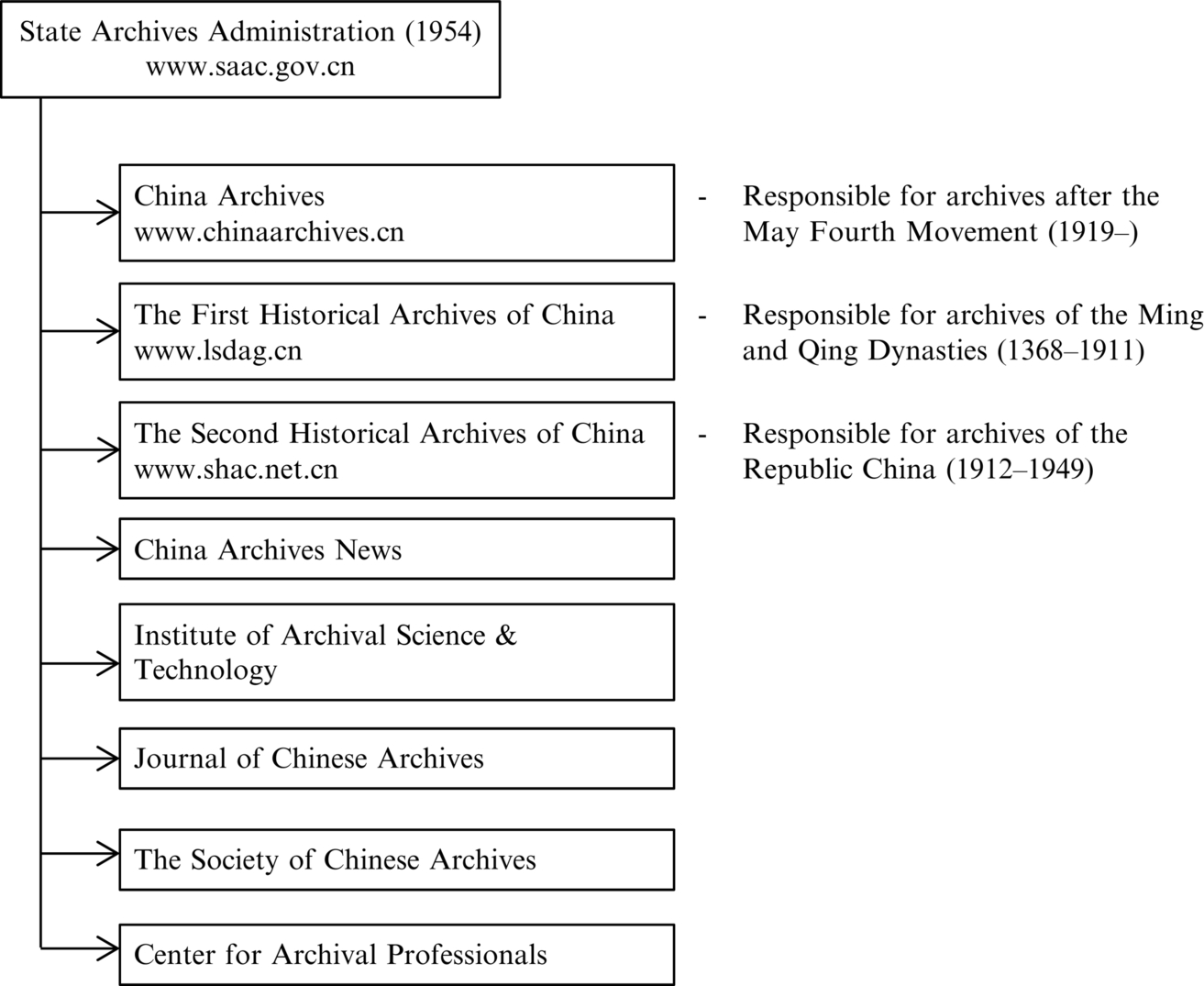

3.2.3 Archives

Modern archives grew from the practice of royal, government, and private collections in Chinese history. Today's archival institutions can be generally categorized into those belonging to the government and those of private as well as cultural and research organizations. Under the supervision of the State Archives Administration, government archives consist of comprehensive ones and those of special purposes and of government agencies (see Fig. 3.4).34 Each level of the government, from the central- down to the county-level, has its own archival bureau which supervises a central archive that is classified as comprehensive and is larger in size than most of other types of archives. The archival bureaus are charged with drafting and implementing policies, accepting and collecting archival objects, managing archives professionally, utilizing preserved content appropriately, editing and publishing historical items, and participating in the compilation of local history.

The numbers in Table 3.4 indicate more archival institutions than libraries in China according to the National Bureau of Statistics. The actual numbers of all forms of archival institutions are much larger if records management is considered to be part of the archival enterprise. The vast majority of large- and medium-sized organizations, including schools, manufacturing plants, and cultural institutions, have their records centers that serve to collect and preserve internal records and archives. Their size corresponds to the size of the host organization; and so are their specialties in content and operation. A standard government records center has branches for general, technology, multimedia, and personnel records, and so on, while other types of records center have their special structures and responsibilities (Table 3.5).

Table 3.4

Total number of archival institutions as of 201318

| Government | Corporate | Cultural institutional | Research institutional | ||

| Comprehensive | Special | Departmental | |||

| 3325 | 240 | 218 | 2182 | 189 | 274 |

Table 3.5

Total number of archival items as of 201318

| Number of archival items | Number of photos | Number of open items | Number of utilized items | Floor space by square meters |

| 447,591,000 | 19,276,000 | 84,900,000 | 14,778,000 | 7,090,000 |

![]()

These archival institutions have played a critical role in identifying, repairing, and preserving valuable historical and contemporary archives. The State Archival Law which was published in 1987 has served to regulate the management of archives, including the structure of archival institutions, policies of archival maintenance, safety and security of preserved materials, and the like.35

For a long time, the quality of archives personnel has been a major challenge to the archival business. Although more than twenty universities have provided formal training in archives for a master's degree, qualified professionals are in great demand. Viewing archival institutions as a place to enjoy relaxing and comforting life, politicians and leaders use their power to send their relatives and friends who lack skills and knowledge in other professions to work there. While the size of staff in many archival institutions has become increasingly bigger over time, capable professionals are far fewer than needed, and new graduates find it difficult to secure a job position in the area they have been trained for. This contrast between a large workforce of incompetents and a small group of knowledgeable employees makes another dichotomy in this territory of scholarship preservation.

3.3 Digital Preservation

3.3.1 A Brief Description

China's investments on digital preservation started in the late-1990s, which was a little later than that in many developed countries.36 In 1996, the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) held its 62th annual conference in Beijing, which became an opportunity for librarians and informational professionals from around the world to introduce their experience in digital libraries and for the Chinese to start planning their own digitization projects. The next year, a national digital initiative, China Digital Libraries Experiment Project 中国实验型数字式图书馆项目, joined by several major libraries including the National Library of China, Shanghai Library, Shenzhen Library, Sun Yat-Sen Library of Guangdong Province, Liaoning Library, Nanjing Library and Guilin Library, was taken and financially supported by the central government. It symbolizes the official start of digital efforts in China. Since then, the central government and local governments have made digitization a high priority and provided a significant amount of funds each year to support the construction of digitization infrastructures for libraries, museums, digital centers, archives, and the like, at the national-, provincial-, prefecture-, and county-levels.

Many digital projects were introduced at different times or simultaneously, supported by major government's grants. For example, for the most recent Digital Library Promotion Project 数字图书馆推广工程 alone, the central government funded approximately ¥0.2 billion CNY (about $30 million USD) each year from 2011 onwards, asking most participating provincial as well as many prefecture governments to match at least 50% of the central government's expenditures for their own digitization activities.37 With such a large amount of financial investments, major institutions for cultural heritages have been able to complete appropriate workflows of digital creation and preservation as well as creating necessary online platforms, of which the National Library of China (Fig. 3.5) has done the most comprehensive work.39,40

As the largest library in Asia and one of the leading libraries in the world, the National Library of China (NLC) holds the largest collections of Chinese literature and historical documents in the world. With its rich collections of rare and precious documents and records from ancient dynasties in Chinese history, including 4000-year-old inscription-bearing animal bones and tortoise shells from the Shang, NLC has been undertaking many ambitious projects on digitizing its archival materials for perpetual preservation and easy access. Among its principal digital projects, the library is particularly proud of the Digital Library Promotion Project, the Network of Chinese Archival Protections 中国古籍保护网, and the China Memory Project 中国记忆, through which not only NLC's own collections but also important archives in many other related cultural organizations have been included as a part of the large-scale digitization.

NLC has extended its cooperative efforts to digitize the acquisitions of Chinese archives stored in overseas libraries. Such international collaborations aim to supplement what NLC does not hold in its inventory in order to assemble a complete corpus of valuable materials for the preservation of Chinese history. An example is NLC's cooperative work with the British Library and a number of institutions in other countries on the International Dunhuang Project 国际敦煌项目 for ancient manuscripts, woodblock prints, paintings, photographs and other artifacts discovered from the Dunhuang Caves 敦煌石窟 on the ancient Silk Road 丝绸之路, dated back to the 4th–14th centuries.

At the same time, provincial, prefecture, and municipal libraries have also witnessed a rapid leap in their digital collections in the past two decades. From the very beginning of the digital preservation efforts, many libraries, archives, and related institutions have formed a long-term development plan by focusing on building a solid foundation, rather than launching separate ventures, in a systemic way in order to avoid redundant work in the future while attempting to serve a larger group of users across a broader region. Below is a diagram that illustrates the structure of a digital library network built for all academic institutions in eastern China's Zhejiang Province (Fig. 3.6). The project designers have an obvious intention to wisely use their money for cross-regional distributions and digital resources sharing. Most of the large-scale digital projects in China have taken a similar consideration into the building of a cost-effective construction and the facilitation of collaborative endeavors.

The digital business in higher-educational institutions has a higher degree of flexibility in regard to funding resources and managerial autonomy. As early as in 1996, Tsinghua University partnered with International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) to exhibit its digital library proposal at the IFLA conference. This joint project has been carried on since then and expanded into a much wider cooperation that includes not only digitization but also many areas of computing, high technology instruction and research, as well as cultural heritage preservation. Today, many higher-educational institutions across the nation have made similar efforts toward a digital campus although each has adopted unique strategies and presented dissimilar products.42,43 Many universities have created a particular academic institute to conduct research on digitization and most recently on electronic resources such as publication databases.

If the early efforts of digitization concentrated on the preservation of historical and cultural heritages, digital libraries have gradually shifted their priorities to diversify their collections, by storing scholarly outcomes and embracing other forms of born-digital resources such as multimedia objects, and providing access to published materials. Instead of measuring a digital collection by its size of digitized documents, librarians and informational professionals presently appraise digital libraries more on the volume of journals, articles, e-books as well as other forms of electronic publications collected in the libraries, and particularly services provided.44 Both publications provided domestically, either in Chinese or in a foreign language, and articles published internationally in English and other foreign languages, are acquired electronically, while the latter are often viewed as a representation of high academic prestige of an institution: the more the better.

This digital development has been accompanied by continuous planning and implementation of relevant policies and procedures.45 A special national committee was formed early on to research, draft and publicize standards for digitization and electronic publishing. Such standardizations have focused on several elements, while metadata management is the most important part because of its complexity in China, including dealing with the traditional and simplified character systems, archival marks, exclusive images, and so on. Below are the major areas of the standardization.

1. Technical requirements, mainly on digitization techniques such as quality control

2. Metadata management, with challenges on Chinese characters and symbols

3. Authority control, involving place, building, personal and organizational names, among others

4. Data standards, also primarily on the uniqueness of Chinese expressions

5. Copyright management, although with different interpretations of it in individual practices

6. Service procedure, more about access which is the topic of next chapter

7. Searchability, more about the functions to facilitate retrieval

In the archival area, digitization efforts also started early and have become a top priority. As early as in 1996, the State Archives Administration established a research group to study electronic file systems.34 The following events represent major progresses in the past two decades:

– In 2000, the first national conference on digital archives was held in Shenzhen

– In 2002, the first national guidelines of building electronic archival information was published

– In 2003, the central government initiated a database for national archives

– In 2007–09, a series of international communication on digitization were taken

– In 2010, a security system was completely implemented for national electronic databases

3.3.2 Some Unique Practices

Metadata research, creation and management have been localized practices.46–48 Although the structures and principles of popular metadata systems in the West, such as the Dublin Core, have been adopted in the building of digital libraries in China, necessary addendums were made to satisfy the special needs for the digital preservation of Chinese materials. This is particularly evident when the complex forms of ancient items are processed; and an example is when various handwritten copies of the same document are digitized, classified, and cataloged. In this particular case, a careful review of the relationship between the original author and the copyists, the relationship among multiple copyists, and the characters of the original as well as each additional copy, becomes necessary and will determine the creation and selection of appropriate metadata elements, and subsequently the easiness to find the digitized items.

Another example is handling the copy of stone rubbings.49,50 Stone rubbings are a popular part of the archival collection in many libraries. The copy of a stone rubbing typically records the inscribed pattern of character writings although graphic images exist as well. In many cases, the inscribed letterings represent calligraphy that displays the individual style of a calligraphist, his fancy penmanship with high esthetic values. Any single inscription may have dual authorship, the one who scripted on the surface of a stone or another type of substances, for example, wood, in ink and the one who engraved the inked writings onto the stone. To make it a little more complicated, the script may not be an original creation, but instead a copy of a third person's work, or the engraving may be the reproduction of another stone sample. Here, we have not yet considered other characteristics of rubbings, for example, a wide arrange of tools, techniques and materials, or time a rubbing was taken, and so on. To catch these variations, a localized design of metadata schema has become a necessity and has been variably made by different institutions.

Romanization represents another unique practice in digital library projects that is more applicable for the preservation and access of born-digital materials than for historical archives.51,52 In addition to the two written systems, namely the traditional and simplified Chinese, the Latin alphabets have been used differently by the Chinese in dissimilar locations and time periods, for example, the Missionary systems (for example, the use of Confucius for 孔夫子), the Wade-Giles system mostly in the English-speaking world and partly in Taiwan (for example, the use of Peking for 北京), the Yale system which is rarely used today (for example, using jr-shr for 知识). The mainland China reformed the Romanization in the late 1950s and since then has adopted Hanyu Pinyin 汉语拼音 which has become the international standard of Chinese Romanization since 1982. It is obvious that computers need to follow one standard of Romanization and at the same time are capable of seamlessly converting between each of the existing and previously used systems regarding metadata management for digital acquisitions, preservation, and retrieval.

In regard to repairing and digitization of rare ancient books and items, Chinese librarians and library technicians have developed their own specialties in response to the particularities of the treated such as the materials, styles of writing and printing, and methods of bookbinding. For instance, in comparison to papers in the West, Chinese papers in the past are lighter, thinner, and softer, if not much coarser, while animal bones and bamboo strips used for carving the early characters are not flat and subject to damage if not treated properly for digitization. At the same time, bookbinding techniques are a particular concern in the process of digitization.

As revealed above, the shortage of qualified staff has been a long-time dilemma for many libraries and archives; and it is particularly evident when digital work has become a central part of collection building. There is an increasing requirement for librarians and archivists to get involved in digitization assignments, while it is what the existing crew members lack. They do not seem to have the capability and desire to learn new technologies. At the same time, trained and experienced personnel in information and computing do not intend to work in either a library or an archival institution because of low salary and benefits there in general. Even those computer experts who have already worked there seek other employment whenever possible. As a contingency plan, many such institutions send selected employees for necessary training; but the results are usually not ideal.

Although government agencies and libraries have paid particular attention to systemizing digitization projects so that standards can be established to reach efficiency and effectiveness, redundant jobs and irregular processing are all around. Differences in practice are between regions and between institutions as the result of lacking communication. On one hand, many major libraries have wasted tremendously on repeating what have been proven to be problematic practices elsewhere, and on the other hand, most small-sized libraries have been short of resources in support of their digitization work. Another issue in the digitization process in China is copyright. The online availability of scholarly information makes it easier for copying and plagiarism, but more difficult for intellectual property protection, which has become a major challenge for information professionals and legal experts, and remains critical in scholarly communication.

3.3.3 Major Databases for Scholarly Materials

Both public and academic libraries subscribe to internationally known English databases such as EBSCO, JStor, and Gale, whenever possible, which is considered to be the essential means of joining international scholarly communication. Some libraries can even afford to provide access to many small and specialized English databases to serve the particular needs of their patrons. The digitization efforts in the past twenty years have successfully brought about numerous Chinese databases, particularly those that contain scholarly materials in Chinese and published in China. Below are several popular ones:

1. China Knowledge Resource Integrated Database 中国知网53

It is a database created by Tsinghua University's China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) project in 1999 and characterized by its comprehensive coverage of academic journal articles, theses and dissertations, yearbooks, conference proceedings, newspapers, encyclopedias, dictionaries, and the like, for all academic disciplines. CNKI's full-text availability of Chinese journals covers the years from 1994 to present. A federated searching function allows users to look for everything inside the database from a single search box, although advanced searching is also possible. This database has provided interactive functionality for users to rate or post comments on covered publications. According to CNKI, it is the largest database in the world for Chinese scholarly materials.

2. Wanfang Data 万方数据54

Wanfang is one of the earliest electronic networks for academic information in China, consisting of several databases such as the most famous one for journals and dissertations. It also collects data published by the government as well as other types of commercial data. As of 7 March 2016, Wanfang Data had collected in total

– 32.9 million academic articles from 1998

– 32.3 million English articles from 1995

– 3 million conference proceedings from 1983

– 3.5 million theses and dissertations

– 51.7 million patents from 1985

– 7.7 million local gazetteers from 1949

– 13.8 million biographies

– 56,456 scholarly reports from 1958

– 48,352 e-books

– And millions of other types of academic data

3. Chinese Science Citation Database 中国科学引文数据库55

Created by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, this database is now hosted by Thomson Reuters as the first database on its Web of Science in a language other than English. The database comprises more than 1200 scholarly publications from China, totaling about 2 million items. It is fully integrated and supports Unicode for Chinese characters searching. With its advanced search functions, users are able to discover subject-based information such as the most recent studies, the most productive scholars and institutions, and relevant publishing venues. It is the earliest database in China, produced as early as in 1989, and is widely recognized as one of the best databases for Chinese scientific literature.

4. Chinese Scientific Journal Database 中文科技期刊数据库56

With a focus on science and technology, this database traces back to 1955 for the full text of scholarly articles. It connects a full array of publications to an online checking system with the aim of providing an automated way of analyzing the originality of text.

5. Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index 中文社会科学引文索引57

This database covers an interdisciplinary citation index in China with a focus on humanities and social science records. It became available in 2000 as the product of Nanjing University, and is now acquired by many Chinese academic libraries. The database contains around 500 Chinese journals of the humanities and social sciences, and is a premier place for scholars to locate scholarly materials.

6. China Academic Digital Associative Library 大学数字图书馆国际合作计划58

This is a multilanguage database which is initiated by Zhejiang University with cooperation from 16 other top universities in China and is serving higher-educational institutions. Started in 2009, the central government has invested ¥1.5 hundred million CNY (around $23 million USD) to cover all academic disciplines for multimedia materials. It is an alternative to CALIS. As of 2014, the database collected a total of 2.7 million items including a lot of archival materials.

7. Founder Apabi eBooks 方正电子图书59

8. Shusheng Zhijia 书生之家60

9. Chaoxing eBooks 超星电子图书61

These databases are specialized in preserving and providing access to e-books and may need special e-reader applications to view the content. Some of the applications can be connected to particular library catalogs and journal databases for the convenience of use. In addition to scholarly materials, the databases also contain literature and other types of reading items.

10. The electronic version of Siku Quanshu 四库全书网络版62

It collects a total of 3461 volumes of Siku Quanshu and provides a full-text searching function. It also provides the modern interpretations of the archival characters, unusual terms, personal and geographic names, and sociocultural contexts for users to better understand the content. Additionally, the product is loaded with online tools for the conversion of the lunar calendar as well as other ancient measures. Users of this site need to download a special application on their own computer.

3.4 Conclusion

Preservation of scholarly materials has been a long tradition in China. However, the preservation practices have varied from time to time, regarding where to, how to, and who perform the work. Much like other activities in scholarly communication, the conducts of scholarship preservation in the present time are full of contradictions. With regard to geographic location, libraries where scholarly materials are stored and accessed have a city-divide and a community-divide, the former of which describes a distribution pattern of library resources between large cities and small towns, while the latter of which explains an uneven allocation of library sites within a city. The reason is simply that the government has not invested enough, and there are no alternative sources to support the development of libraries and archives.

As to the labor force in scholarship preservation, there is a contrast between the large number of staff at work and the small number of professionally trained employees. Libraries and archives are considered to be places for people to lie down on the job. Unattractive to young computer specialists, this contrast is notably costly when digitization has become the essential means of preservation. In small-sized libraries and archives where resources are comparatively limited this contract is more noticeable than in leading institutions that can afford to draw capable people with adequate financial support for major projects from the government as well as other sources.

However, the Chinese have every reason to be proud of their achievements in scholarship preservation. Within a short time span of about twenty years, they have built many splendid structures for libraries and archives and have repaired and digitized enormous valuable documentation to preserve the culture and history of China and support scholarly activities. Their endeavors in globalization have indeed brought Chinese scholarship into a worldwide attention which is partially indicated by abundant international collaborations in digital preservation.