Assessment

Which?

Abstract

Assessment of scholarly outcomes is based on certain bibliometric indexes that indicate the quality of the work. It is found that Chinese researchers have made tremendous contributions to scholarship regarding the number of their publications in international journals. However, these numerous publications are not cited adequately because of their quality (?) or language (?). It is indeed true that English is an obstacle for the Chinese in the process of writing scientific articles. A performance difference between scientists and social scientists is also discovered. In addition, this chapter highlights the achievements that the Chinese have made in scholarly publishing and patent creation.

Keywords

SCI; Chinese bibliographic indexes; Citing behavior.

6.1 Some Background Information

In the early 1960s Eugene Garfield, a pioneer in bibliometrics and scientometrics based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, founded the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI), which presently is a major part of the science division of Thomson Reuters Corporation. ISI offers bibliographic database services specializing in citation indexing and analyses. It contains the Science Citation Index (SCI—now known as the Science Citation Index Expanded, SCIE), the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), and the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (AHCI) to provide data of carefully selected journals and articles on their citing and cited numbers. Using the data the Journal Citation Reports (JCR), which is another integral part of ISI, annually measures the indexed journals according to how often they are cited in recent journals and uses this information to indicate the indexed journals’ academic impact.1 Because of the rigorous process these indexes use to select journals, ranking journals by impact factor is widely respected by the international scholarly community as the primary means for assessing the quality of scholarship.

It was not until the late 1980s that the Chinese started incorporating the journal ranking scores into their own academic evaluation mechanism.2 The original purpose for consulting JCR was to construct objective assessment criteria that are based on peer review and that are popularly accepted by the international academic community. Policies and practices implemented at certain levels of the Chinese government and by research and teaching institutions were soon used to guide tenure, promotion, and other types of professional advancement. Publishing articles in SCI-indexed journals has since been seen as the way to boost the reputation of an institution or individual and thereby help to secure funding for grants and academic prestige. This great attraction to SCI has happened more in science, engineering, and the health sciences than in social science and the humanities. As of 2007 China was the third largest SCI paper producer in the world, only after the United States and the United Kingdom, and its standing has continued to advance.

There is nothing wrong with seeking the bibliometric approach in scholarship assessment. But when it becomes the only criterion of academic evaluation, skepticism arises. First, journal ranking by impact factor has many serious flaws, such as the use of self-citations to promote the rank of a journal as described in Chapter 2. Second, publications on popular subjects tend to attract more citations than publications on unpopular subjects. Third, longer articles and review articles are more often cited.3 More importantly, the overwhelming majority of Chinese journals have not been collected by SCI, and both SSCI and AHCI databases rarely index Chinese journals because of language barriers and other historical reasons.

The Chinese’s enthusiasm for SCI publications places tremendous stress on researchers. Although numerous scientists are making contributions to SCI journals, mostly in English, they represent a small number when compared to the number of Chinese authors whose research subjects may be SCI-irrelevant, whose professional training may be inadequate, whose English-writing skills may be insufficient, and so on. When journal ranking is attached to academic status and monetary reward, for example, China Agricultural University once offered a reward of ¥1 million CNY, about $154,000 USD, to anyone who could be the corresponding author for a Nature, Science, or Cell paper, the objective assessment of scholarship is no longer what it was designed and expected to be. Some critics have referred to SCI as the Stupid Chinese Index or the Silly Chinese Index to express their anger and helplessness in face of the practice.2

6.2 Bibliometric Assessment of Research Activities

6.2.1 Chinese Publications in SCI and SSCI

Some bibliometric analyses have examined the Chinese research performance that is made available through SCI.4,5 One of the studies focuses on the period 1980–99 for a total collection of 162,741 articles in about 5980 journal titles.4 All these articles have a “Chinese address,” indicating in the authors’ address field that they are authored and coauthored by someone from an institution located in China. These journals are categorized into three groups, namely, journals in which more than half the articles are written in Chinese, journals that contain articles written in English but with the majority of the authors from Chinese institutions, and all other journals.

When articles in all groups are measured, the average number of citations per article is 1.51, not counting self-citations. As many as 65% of the articles have not accumulated any citations, again not counting self-citations. This citation percentage is significantly lower than the world average, which indicates Chinese publications’ low impact on global scientific research. When analyses are made at the group level, journals with articles published in Chinese have a similar low impact, and so do the journals with articles published by Chinese authors but in languages other than Chinese. Both have a high percentage of uncited articles. However, the all-other group of journals presents the opposite result; in particular journals in materials science enjoy a status higher than the average world status and perform well in their own subfields. Hence it does not appear that a publications’ language is a dominant factor for the low citation rates.

This study suggests that when measuring the impact of Chinese studies, it is more appropriate to use data collected in Chinese bibliographic databases that provide relatively complete coverage of Chinese journals so that an apples to apples comparison can be made. On the other hand, the assessment of Chinese publications based on the total collection of journals in the SCI index may provide a diffused picture because of the low percentage of Chinese journals presented there.

Nevertheless, this suggestion seems to be no longer very pertinent today. Even with data from the SCI database itself, a rapid increase in citation rates has been observed since the turn of the new millennium. Another bibliometric analysis compares the impact factors of Chinese publications with those of other countries using US data as the benchmark.6 The results show that the China-US ratio was 26:100 in 1990 and increased to 55:100 in 2010 for the average citations. Although findings show China still trailing the United States in producing the top 1% of highly cited articles, China is tied with the United Kingdom and Germany and surpasses all other major countries such as Japan and India. The China-US ratio in the percentage of highly cited publications increased steeply from 6:100 in 2001 to 31:100 in 2011.

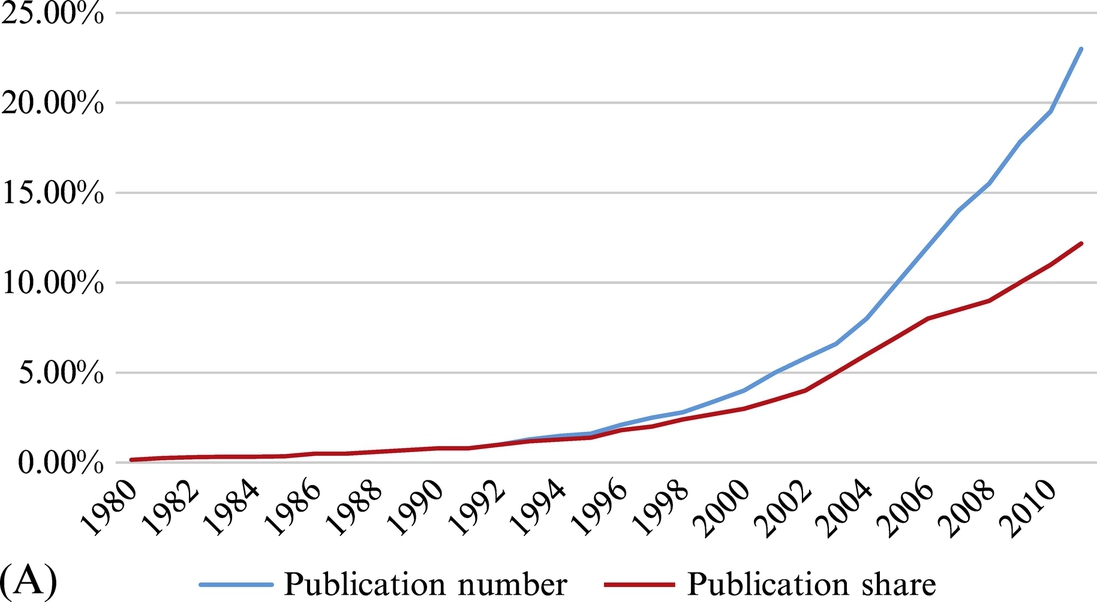

Another study covers a longer time span, 1980–2011, on the numbers of publications authored by Chinese scientists and their citations.7 This study reveals an abrupt growth of these numbers after approximately 2000 with data not included in the previous study (see Fig. 6.1). These figures show that the absolute numbers of citations and publications escalated after the turn of the new millennium at a greater speed than their world shares. Proportionally, China’s publications have not been able to receive the same impact in the global scientific community, which is similar to what the previous study found, as shown in these two figures by the red lines.

The same study divides Chinese publication activities in the past three decades into four major stages: the restoration stage from 1977 to 1984, the initial stage of the reform from 1985 to 1994, the deepening stage of reform from 1995 to 2005, and the raising stage from 2006 onward. Each stage corresponds to changes in the Chinese government’s investment in science and development as well as in new policies implemented to guide scholarship assessment. This study also points to a utilitarian practice nationwide in China that emphasizes a social function of science for economic and political applications rather than the quest for concealed scientific fundamentals. One result is an uneven distribution of investment across disciplines that favors applied sciences over basic sciences and across institutions that backs selected institutions. At the same time both institutions and individuals seek fast and noticeable returns for their scholarly efforts, which inevitably inflates publications. Even worse, when personal pursuit for academic gain is in conflict with the government’s interest in social development, research activities lose the original utilitarian attributes and are oriented only by SCI achievements with many valueless projects.

A longitudinal rise is even higher for social science publications. In the late 1970s China did not have noticeable representation in the SSCI index; however, as of 2007 a total of 1507 articles were uncovered.8 Disciplinarily, China has produced more publications in the fields of business administration and economics than in psychology and social, political, and communication science. A comparison to other major contributing countries reveals that China is at the fifteenth position in the world share of citation numbers, which is four positions behind its total number of publications. It needs to be stated that social science subjects are inherently more nationally oriented and are often expressed in national languages.9 China’s performance in social science research, based on the SSCI data, is highly comparable to other major non-English-speaking countries such as Japan and South Korea.

A considerable expansion of social science and humanities publications in SSCI is observed after the turn of the new millennium. Within about 10 years, the total of such articles authored by the Chinese reached more than 23,000, with extensive collaborations with authors from other countries, particularly the United States, Hong Kong, and the United Kingdom.10 This growth correlates with the rapid increase of funding expenditures and monetary awards for SCI and SSCI publications. It is recorded that some institutions award ¥10,000–¥100,000 CNY (about $1523–$15,228 USD) to the first author or corresponding author of an SSCI or AHCI article.11 At the national level, when the Chinese government started recognizing its past inattention to the development of social science and humanities studies, the focus of investment shifted beyond science and technology.

6.2.2 Chinese Bibliographic Indexes

In the late 1980s the State Science and Technology Commission (now known as the Ministry of Science and Technology) decided to create a database to index and evaluate research articles and journals in the Chinese language and published in China. The database, China Scientific and Technical Papers and Citations (CSTPC), is a Chinese version of SCI and JCR, which are the integrated parts of ISI. As a Chinese product, CSTPC collects journals registered and published in China with a disciplinary focus on natural sciences, technologies, and health sciences.12

Instead of simply collecting all journal publications, CSTPC employs a set of criteria to select journals that are internationally indexed and that are recognized core publications in China’s academia. Only research articles in these journals are included and measured. The first author’s research affiliation is assembled for the analysis of scholarly performance by institution, as well as other pertinent information such as the funding source(s) of the research, the involvement of international or domestic collaboration in the research, and the waiting time for publication.

The academic society rapidly responded to the information collected in the CSTPC database. The official China S&T Statistical Yearbook soon started quoting numbers from the database to report scholarly progress, which attracted the immediate attention of numerous university administrations and individual scholars. The assessment approaches adopted by the database also helped educate authors on how to conduct scientific studies and write professional articles.4 For example, research articles in China in the past tended to provide a very limited number of references in order to save space and cut costs for the journals, and some journals mandated a short list of, or even deleted, references when they were beyond a given number. The importance of references cited by an article in measuring a journal’s impact factor has prompted the Chinese to increase the number of references to their publications.

In addition to quantitatively assessing journals, CSTPC also ranks institutions by scholarship and analyzes international collaborations among many other functions. For example, it listed the United States, Japan, Hong Kong, Germany, and the United Kingdom as the top countries with the most coauthorship with Chinese researchers in 2000. This database helps related government agencies make or adjust their policies guiding scientific research and connect the Chinese academic conduct to the global research contributions.

Because SCI is known for lacking non-English journals, CSTPC is an appropriate alternative for the Chinese. Another database similar to CSTPC is the Chinese Science Citation Database produced by the Documentation and Information Centre of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Some studies have been taken to compare SCI and these two databases.13,14 It is found that articles in journals collected in CSTPC provide fewer references than those covered by SCI. While the articles published in top-ranked Chinese journals tend to cite more in international journals than in domestic journals, the same is not true the other way round, meaning that authors publishing in international journals have paid less attention to articles in Chinese journals. Regarding the visibility of Chinese publications, though not high in general, articles in materials science have done a better job than research in the life sciences. The evidence here also shows that language plays a role in the global visibility of Chinese publications; for example, top-ranked English journals published in China have attracted more citations than their Chinese counterparts.

The results of the comparisons confirm that publishing in international journals is the best option for raising one’s scholarly visibility, and the second option is to publish in top English journals that are published in China. The findings once again highlight the benefit of undertaking international collaborations. When English writing is impossible, one will need to try a Chinese journal that has been indexed by CSTPC. It is common for Chinese authors to compete strongly to publish in top journals at all levels.

Similar analyses of Chinese publications reveal that Chinese authors provide fewer literature reviews than their international counterparts, particularly reviews of research literature in English, which may indicate their limited access to scholarly literature. For example, one study finds that less than 3% of the higher educational institutions in China subscribed to the SCI database in 2004.5 This situation has improved since then because of an increasing amount of government funding and the availability of open-access publications.

In addition to databases for science and technology, the Chinese developed its Chinese citation database for social science in 2000, the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI), which is under the supervision of the Chinese Social Sciences Research Evaluation Center. In the fields of the humanities and art, another citation index was created in 2000, the Chinese Humanities and Social Science Citation Database (CHSSCD), which is under the supervision of the Centre for Documentation and Information and affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.15 Both databases contain citation data for recognized journals in social science and the humanities published in China.

A comparative study on communication structures of Chinese journals in the social sciences shows an inadequately structured system.16 Using data from both the domestic CSSCI and the international SSCI, it is found that social science publications have fewer references than international publications, and also fewer than publications in natural science publications in China. In general, social science disciplines in China are far less specialized than social science fields in the world regarding disciplinary delineations. The low scale of subject specialization in the social sciences explains why China has lagged behind the West in its intellectual domains. Citation patterns in three social science subjects, namely political science and Marxism, library and information science, and economics, are comparable to those of the international ones; but Marxism studies are more established than political science in China.

Compared to scientific conduct, research activities in Chinese social sciences are not evaluated by an objective standard, which is the result of the unspecialized and localized subjects in China and the neglect of its scholarly community to develop quantitative measures to regulate publications. Hence plagiarism and other types of academic misconduct are often discovered in social science investigations. Another possible improvement is to increase internationalization efforts in social science fields in order to bring in globally practiced routines and create more worldwide communication.

6.2.3 Collaboration Measures

Some quantitative studies of interinstitutional collaborations use publication data and citation indexes to examine the behavior of coauthorship and collaborative characteristics in China.17–19 The number of authors in a publication is considered to indicate the degree of cooperation, and the intensity of collaboration is measured by collaboration scores that count the relationship between authors and their affiliated organizations. The study finds that most collaborations are done between institutions in the same geographic location. This region-bound pattern of academic collaboration seems to underscore scholars’ preferences for easily sharing resources and efficient communication. There is more collaborative work in science and technology than in social science and the humanities.

Institutional research activities and their applications to industry have been evaluated. One study finds limited coauthorship between academic and industrial researchers, but also notes an increasing number of research collaborations with industries in scholarly activities and scientific contributions in China.20 In another study, longitudinal progress is discovered that suggests an ever-increasing positive relationship between the academic world and the world of practice.21 As an indicator of scientific and technology research for social good and economic development, such a positive relationship signifies an emphasis of institutional and individual efforts on encouraging innovations and productivity and an increasing access to science by industry. There are also growing cases of co-patenting, knowledge transfer, and joint research between universities and industrial firms that have helped facilitate creative outputs that benefit society.

Regarding geographic comparisons for scholarly publications and citations, a provincial-level analysis is taken to examine regional research profiles.19,22 It is not surprising, with an uneven distribution of R&D investments, to observe a similar uneven distribution of scholarly publications and academic impact across provinces where developed regions such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Jiangsu have made greater contributions to science than developing regions in China’s inland provinces such as Qinghai, Gansu, and Tibet. A geographic difference in the research of varying academic disciplines is also discovered because of historical traditions and geospatial distinctions. For example, scholarly pursuits in the geosciences and space sciences have been active in some regions where other research subjects may not be so prolific, while marine studies are the emphasis of research in many coastal provinces. Moreover, there is disparity between publication numbers and citation numbers across regions; for example, some provinces have been able to produce more numbers of citations than of publications, while other provinces are doing the opposite.

6.2.4 Examinations of Patenting Activities

When China became one of the most productive countries in patent applications and approvals, research was taken to analyze the characteristics of patenting activities such as patent types, areas, figures, citations, and inventive models.25–28 Although patents fall in virtually every area of academic studies and industrial domains, innovative performance in information and communication technologies (ICT) is given special attention. A study examines the impact of patent output from a historical perspective by focusing on regional differences and development, characters of inventors and their institutions, as well as their collaborative strategies. It is discovered that collaborative efforts between industrial entities are the most popular ones, while research institutions have made only secondary contributions. Major industrial firms, such as the Huawei Corporation and Lenovo Corporation, have played a primary role in the patent productions of the Chinese ICT enterprise.

Almost all patent-related studies denote geographic differences in patent activities.29 For example, a big gap between the coastal regions and the inlands seems to be very obvious, particularly that Beijing, Guangdong, and Shanghai have been in the leading positions for many years, and the gap has grown even wider at the present time and will probably do so in the future. It is also interesting that upon comparing the top performers a market-oriented environment is discovered to be superior to an administration-oriented arrangement for encouraging technological innovations and advancing collaborative productivity. A change in policies is therefore necessary to improve the efficiency in transmitting knowledge and build effective innovation networks.

One study examines technological in-licensing of Chinese industries by identifying their patent history to verify whether the standing patent citations in the patent collections of Chinese firms are sufficiently cited, and thus learned from, their previously in-licensed technologies within a five-year period.26 The finding is rather positive, revealing that many licensee firms utilize licensed technologies to construct their technological capabilities. The importance of implementing appropriate policies to foster indigenous innovations based on a firm’s internal R&D expenditures also becomes evident.

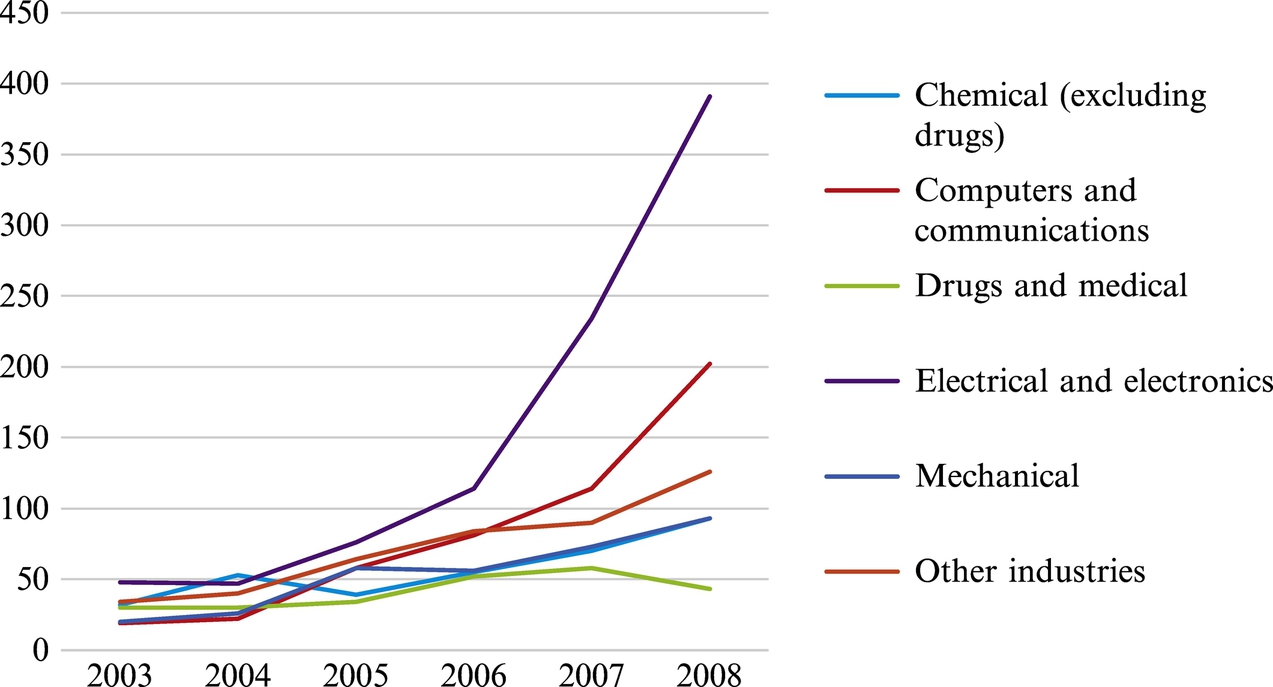

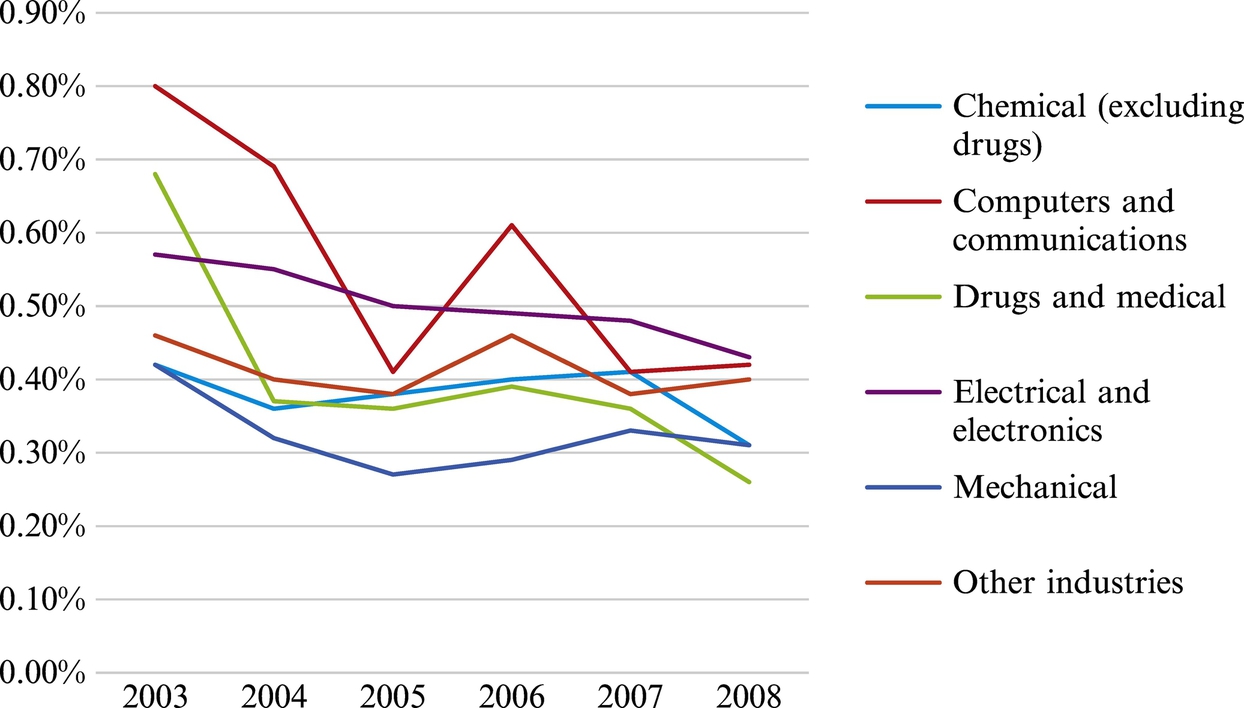

Much like the discoveries of Chinese publications and citations as previously described, however, Chinese patents also present a lower rate of citations than that of patent applications and approvals. Again, this is the inevitable result of relevant policies in China that concentrate much more on quantity than quality of patents and R&D performance. In other words, even though the number of patents has dramatically increased in the past decade, the number of citations has not caught up. As a matter of fact, a comparison between the two sets of numbers even shows an annual decrease of the citation number per patent from 2003 to 2008 (Figs. 6.3 and 6.4).

6.3 Behavior Observed

Bibliometrics speaks of behavior, but may not always describe the reasons behind the behavior. Bibliometrics also has many other limitations in terms of measuring scholarship; for example, it is not necessarily true that numerous citations indicate a high-quality publication. The number of citations may mean different things in different academic disciplines, or on different publishing venues, or when a topic is popular versus unpopular; yet we have not mentioned variations created by the use of language, the means of publication (e.g., on social media), and the existence of self-citations. Qualitative investigations, such as questionnaire surveys, interviews, and ethnographic observations, may be able to provide other forms of evidence to help people understand publication behaviors in the process of scholarly communication.

A recent study of Chinese scholars in scholarly communication behavior and trust is such an effort that imitates an international investigation funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation on English language publications by US and UK researchers.30 By responding to particularly designed survey questions, a group of Chinese respondents with an average age of 33 provided answers that helped the investigators understand how the young generations of scholars in China perform in scholarship use, citing, and publishing and how trust is exercised in research activities.

Chinese researchers differ from their international colleagues in that when they read research literature, they pay more attention to abstracts and check whether the arguments and logic presented in the content are sound. This may be the reason for the pervading attitude among young generations for quick success and instant gain, which is partly the result of the pressure to publish to gain career promotions. The more articles people publish, the better their chance for professional advancement; and the higher their journals are ranked, the higher their competitive position for academic resources. This observation is further supported by other discoveries showing, for example, that Chinese researchers pay more attention to journal impact factors and are more likely to be influenced by institutional directives than their international colleagues.

Guanxi, which refers to the basic dynamics in personalized networks of influence, is a central notion in Chinese society. Within the networks, individuals develop relationships with others for the intent of reciprocity. This practice is also reflected in scholarly conduct as Chinese researchers are very likely to read an article recommended by a colleague when they select sources for their research projects. They tend to trust people within the personalized system more than other sources of information. If “guanxi is absolutely essential to successfully complete any task in virtually all spheres of social life,”31 one will naturally expect its presence in Chinese scholarly communication.

Regarding citing behaviors, Chinese researchers prefer seminal information sources that are both current and highly cited by others. As previously mentioned, the impact factor of a journal is what authors consider in determining what to cite, and it also directs the preferred publication venue for their own work. International journals in English are, of course, among the top choices. The Chinese also tend to submit their research drafts to traditional kinds of publications, for example, academic journals, rather than open-access ones or other types of social media tools. But if an open access journal is peer-reviewed and has a scholarly reputation, it is also acceptable.

6.4 Conclusion

About 10 years ago through an analysis of citation patterns, researchers noticed that the communication scope of Chinese journals was primarily restricted to the scholarly community within the country.34 An unbalanced distribution of scholarly output was detected in which knowledge principally flowed in rather than out of Chinese academia. Although China became one of the primary countries in the world in the production of scholarly publications, its impact on international research activities was not able to capture the rapid growth of publications. Hence a visible and wide contrast between the number of articles published in international journals by Chinese authors and the number of citations they received was discovered in many bibliometric studies. Scholarly collaborations, particularly the international ones, have helped to improve the scholarly impact of Chinese publications.

Within China a geographic contrast in scholarship is also found between the eastern coast and the inlands, with a few developed areas, mainly Beijing, Guangdong, and Shanghai, producing more research in the form of research papers, citations, and patents than many developing provinces and municipals. This regional difference is primarily connected to the government’s investment in science and technology, the implementation of relevant policies, and particular educational practices, as well as historical and cultural traditions. It is also correlated to an existing ICT divide in information availability, access, and use.

A similar dichotomy of research outcome is detected between different research and instructional institutions. While some have been able to build world-class reputations in scholarship, others are fighting simply for access to necessary research data and information. A few highly ranked universities, such as Peking and Tsinghua Universities, have shown cases of scholarly productivity and impact, while other institutions may fail to appear in internationally indexed journals, either in English or in Chinese. Domestically, research collaborations are usually made within a small group of elite universities and sometimes are bounded by geographic proximity.

During the past two decades numerous bibliometric studies were conducted and published to evaluate the achievements of Chinese scholarly communication. This chapter introduces only a small portion of the literature and findings. Missing from the preceding descriptions are case studies of bibliometrics for more academic disciplines,35 individual institutions,36 dissertations and theses,37 and the like. In one internationally published bibliometric journal, that is, Scientometrics, numerous articles are available for quantitative examinations to assess scholarly performance of Chinese research, many of which also point to the narrow-minded policies that put pressure on publishing only in the venues indexed by SCI, sometimes referred to as the Stupid Chinese Index.