Preparations

Who?

Abstract

Higher education in China is introduced by following a historical framework, yet with an emphasis on its current situation. Policy implementations in the past four decades and their influences on the transformation of higher learning in such areas as college preparation, admissions, the population of students and faculty, the building of institutional infrastructure, and so on are briefly described. The chapter focuses on explaining various binary practices in higher education, including an unequal distribution of educational resources between junior and senior faculties as well as between urban and rural students.

Keywords

History of higher education; Gaokao; Cram school; College life; Universities.

A simple search in Google using “scholarly communication cycle” as the search term for images would return copious diagrams that model a scholarly communication lifecycle with each traceable movement of scholastically related work, which, in some cases, subordinates a knowledge cycle, a publishing cycle, an access cycle, and the like. The majority of these models represent an understanding of librarians and publishing professionals toward scholarship creation, assessment, dissemination, preservation, and use. Rarely does a diagram, however, acknowledge higher educational training as the necessary preparation in a knowledge cycle, through which the future scholars are exposed to a broad array of academic fields and modes of inquiry and through which students develop their abilities in critical thinking and problem solving to succeed in the areas of their choice. The consideration of higher education as an integral part of the scholarly communication process becomes particularly relevant when referring to the fact that higher educational institutions have made the dominant contributions to scientific explorations in most countries, including China, and have helped prepare generations of scholars. In the following descriptions, the terms school, university, college, and institution are used interchangeably unless otherwise defined.

1.1 Higher Education: A Brief History

1.1.1 Ancient China

The Chinese are inclined to trace the history of major modern developments back through time in order to decipher possible prior trajectories, and they will not be disappointed in this case. China does have an extended tradition of higher education with many of its practices created and implemented earlier than those in the West.1–4 For instance, a maturely developed structure of private higher education was well documented as early as the Spring and Autumn Period 春秋 (770–479 BC), while specialized college curricula in such areas as medicine, law, mathematics, and astronomy originated in the Southern and Northern Dynasties 南北朝 (AD 420–589) and refined in the Tang Dynasty 唐朝 (AD 618–907).

From the very beginning of higher education in the Xia Dynasty 夏朝 (c.2070–1600 BC) and Shang Dynasty 商朝 (1600–1046 BC), there have been two parallel, though not necessarily contradictory, systems in Chinese history. A private educational structure was characterized by Confucius 孔子 (551–479 BC), who as a renowned teacher and philosopher had personally trained as many as 3000 students.5 The time of Confucius witnessed a great degree of prosperity in school development which was an early epoch of training for the masses. Since then, private education has experienced considerable fluctuations from time to time, representing concurrent political as well as cultural, economic, and military conditions. One can discover a boom in the number and quality of private schools such as shuyuan 书院 in the Han 汉朝 (202 BC–AD 8, and AD 25–220), Tang, Song 宋朝 (AD 960–1279), and Ming 明朝 (AD 1368–1644) Dynasties on one hand, and their downturn in the Jin 晋朝 (AD 265–420), Yuan 元朝 (AD 1271–1368), and Qing 清朝 (AD 1636–1912) Dynasties on the other hand.

State-run schools were another tertiary system similarly popular in Chinese history.6 Started in the Xia and Shang Dynasties, though poorly documented in records, such schools gained their momentum in the Han Dynasty when taixue 太学 (similar to today’s royal college) was established in 124 BC. By the end of the dynasty, more than 30,000 students had enrolled in taixue.7 In subsequent empires, the taixue tradition was carried on, improved, and expanded to include other forms of state-run schools like guozixue 国子学 in the Tang and Song Dynasties and guozijian 国子监 in the Ming Dynasty.

Regarding the philosophy of education, understandings and practices were divided. Though there were Hundred Schools of Thought 诸子百家 during the Spring and Autumn Period when philosophical thoughts and pedagogies flourished,8 Confucianism became the national educational doctrine during the Han Dynasty and remained so throughout Chinese history. Based on the teachings of Confucius, Confucianism embraces an ethical and sociopolitical ideology that underscores the principles of society and government and that emphasizes codes for personal conduct that have fundamentally influenced Chinese education. On the other hand, pragmatism, always prevalent in the curricula, effected a content of education that stressed transmitting knowledge from previous to the younger generations, providing them with right directions and guidance according to their natural interests, aptitude, and capabilities.9

Both the state-run and private schools were normally headed by famous scholars, such as Han Yu 韩愈, a precursor of Neo-Confucianism and a popular essayist and poet in the Tang Dynasty, who was assigned to lead the imperial guozixue; and Zhu Xi 朱熹, an influential rationalist and scholar in the Song Dynasty, who supervised the private bailudong 白鹿洞 and yuelu 岳麓 shuyuans. Instructors were also scholars and were referred to as “doctors” and were responsible for developing curricula and teaching students. Though elite education could be noted at times, school doors were generally open to students of diverse backgrounds. In some dynasties, especially in the Tang and Song Dynasties, students from Japan, Korea, and other neighboring countries were found throughout these schools.

Formally started in the Tang Dynasty, a civil service examination tradition, keju 科举, was designed to select intellectuals as qualified officials.10 Even if each following empire reformed the system to meet its own sociopolitical requirements, the exams adhered to a standard that tested knowledge of the classics and literary styles, rather than technical proficiencies, with essay questions to test an exam-taker’s understanding of the Confucianism doctrine. Although the exams served more as a political mechanism to procreate “the relations of knowledge and power between society’s elite and the monarch’s subjects,”11 aiming at producing a gentry class of scholars- bureaucrats, than as a routine to guide educational conduct, they did have a crucial impact on the development of higher education in ancient China. For example, abundant private schools were built to prepare students for the exams. The keju practice lasted about 1500 years and was ultimately abolished by the government in the late Qing Dynasty to give way to modern higher education introduced by the West.

1.1.2 The Premodern Era

In the mid-1700s an industrial revolution began in England and soon spread to Western Europe and North America. This revolution was characterized by a series of transitions of manufacturing processes from hand production to machinery assembly that improved efficiency in industry, started the modern capitalist economy, and changed every aspect of the daily life.12,13 On the other side of the globe, however, the concurrent Chinese government was implementing a closed-door policy that particularly prohibited foreign merchants from trading opium in China. An Anglo-Chinese dispute over British trade and China’s sovereignty brought up the Opium Wars 鸦片战争 between 1839 and 1860.14 When China was defeated in the wars, it was humiliatingly forced to open its door to foreign trade, and consequently to the Western style of technology, culture, and education.

Because the openness was compelled, an introduction of Western education to China encountered resistance. It is, therefore, not surprising to observe a gradual, rather than immediate, acceptance of the Chinese to Western-style education.15–17 At the beginning of the changes, only technical schools that taught science, technologies, foreign languages, and military training were allowed. Later schools for teachers were created. It was not until the Nationalist Party 国民党 established a republic China in the 1920s that Western institutional structures and educational principles finally found their way to replace the classical methods of Chinese teaching and learning.

State-run universities were mushroomed in this time period. The republic government granted scholars and administrators necessary autonomy to reform traditional schoolings and adopt Western-style higher education. Most of these educators received various levels of training in Japan, the United States, or European countries and therefore were able to bring back what they learned and observed in the West to China to build the models that kept the essence of Western education and were also acceptable to the locals. Under their leadership, by 1947 around 200 universities had been inaugurated and in normalized operations, with the number of undergraduate students approaching 155,036, a graduate population of 424, and faculty members reaching up to 17,600.18 Of particular renown is Peking University 北京大学 in Beijing, which was one of the first comprehensive universities in China and has remained among the best in the country for more than a century.

Under the republican government’s Regulations Concerning Private Universities, private education continued its tradition and also experienced a rapid growth with various resources of support. The resources included foreign industries such as Tongji University 同济大学 in Shanghai, which was created by German industrialists; local sponsorship such as Fudan University 复旦大学 in Shanghai and Nankai University 南开大学 in Tianjin, both of which were created by Chinese educators; and Xiamen University 厦门大学 in Fujian, which was created by an overseas Chinese merchant. Most of these private institutions were later transformed into nationally operated universities for political and financial reasons.

Missionary institutions made another major contribution to the development of modern Chinese higher education, although these institutions and their student enrollments were relatively small. The well-known missionary institutions included Yenching University 燕京大学 and Saint John’s University 圣约翰大学 of Christian affiliation and Furen University 辅仁大学 and Zhendan University 震旦大学 of Catholic affiliation. Many of the missionary institutions followed a liberal arts tradition that emphasized basic sciences, social sciences, and humanities and pioneered Chinese higher education in accepting women. They were also among the first to confer graduate education and award master’s degrees in restricted areas.

The government and educators made efforts to standardize institutional structures and educational systems. An official guideline, the University Order 大学令, was initiated in the 1910s and finalized a little later after some cycles of practice to authorize faculty control over university curricula and to formulate institutional organization. Around the same time, the Degree Conferment Act 学位授予法 was released to regulate degree granting for all types of tertiary institutions. Such serial efforts of standardization gradually formed a national educational system that many saw as a cloning of the Western model.

1.1.3 The Early Stage of Communist Control (Prior to the Late 1970s)

When the Communist Party 共产党 came to power in 1949, it decided to remodel higher education according to its own ideas. At the First National Work Conference on Education, the new government discussed a proposal to possibly draw upon the Soviet Union’s experience with education. China’s unexpectedly military confrontation with the United Nations force, primarily the United States, in the Korean War 朝鲜战争 left it with no option but to keep to the Soviet model. In the following years, a series of restructuring took place, including strengthening the predominance of public ownership, ensuring central planning, emphasizing technical training, and politicizing institutional management.19

The idea of public ownership placed all tertiary schools under the control of the communist government. The central Ministry of Education, jointly with provincial and sometimes municipal governments, was responsible for overseeing the administration of institutions of higher education. Personnel, namely that is institutional officials with appropriate bureaucratic ranks, were assigned and budgets were allocated by different levels of the government. Moreover, the communists unified other educational conducts, from student admissions to curriculum development, and even graduate placement was controlled by the government, which assigned a position to students at their graduation.

Comprehensive universities were reorganized to become specialized ones. For example, the top two nationally known universities, Peking University and Tsinghua University 清华大学, both experienced major changes, with the latter one being converted into solely an engineering institution and the former one becoming a science- and social science-focused university. Their subordinate professional schools gained an independent status, and each became an individual institution specializing in one subject. As a result, the number of specialized colleges increased significantly. Under the Soviet model, although professors were still conducting scientific studies, research activities were moved out of educational entities and became the main responsibilities of the scholars in research-only organizations such as the Chinese Academies of Sciences 中国科学院, Social Sciences 社会科学院, and Engineering 工程学院.

This educational reform to accept the Soviet Union’s paradigm had a short lifespan of approximately one decade. Although the official return to Western standards did not occur until the late 1970s, the Chinese instantly abandoned the centralized planning practice after the break up with the communist-led Soviet Union in the late 1960s. The years in between were the timeframe in which Chairman Mao 毛主席 launched a 10-year Cultural Revolution 文化大革命 during which time higher education essentially came to a halt nationwide, with faculty being sent to work in rural farmlands.

During the Cultural Revolution the authority of all universities was taken out of the hands of campus administrations and faculty as they were considered by Chairman Mao to be responsible for providing only an elite education beyond the reach of the masses. In the beginning, college students became the Red Guards 红卫兵 and took part in the political disorder. When universities resumed business some years later, the propaganda teams of the Red Guards, soldiers from the People’s Liberation Army, and factory workers captured the power on curriculum arrangement and everything else. Instruction was entirely concentrated on practical needs that emphasized teaching of technical skills, agricultural expertise, general medicine, and so on. Many liberal arts subjects such as philosophy, history, geography, sociology, and the like were indefinitely closed.

1.2 Modern Education Since the Late 1970s

1.2.1 Introduction

Since it was first introduced in China approximately 100 years ago, the modern system of higher education has experienced a rather bumpy development. Varied practices reflect concurrent political and sociocultural conditions. A chronological description will help illustrate each phase of the development. Please note that, in the following list, the starting time is randomly picked for a rough representation, and the ending time is at the time of this writing.

| 1916–37 | The early time with diverse practices, resulting in an adoption of the Western standards |

| 1937–45 | The Sino-Japan Way 中日战争 when Japan invaded China and interrupted much of its education |

| 1945–49 | The Civil War 解放战争 between the Communist Party and the republic government that disrupted educational activities |

| 1949–57 | Transformation of higher education from the Western to the Soviet models |

| 1957–66 | The breaking of relations with the Soviet Union that stopped the Soviet model, and the Anti-Rightist Campaign 反右运动 that alienated intellectuals and harmed educational conduct |

| 1966–76 | The Cultural Revolution that brought higher education to a pause |

| 1976–2016 | An ongoing process of educational reform that has brought the system back to the Western style, in particular the US model |

The preceding list makes it apparent that several major intervals (italic) in recent Chinese history were difficult times for higher education, and the best and longest time period is from 1976 onward when the Communist Party decided to stop the Cultural Revolution and focus on economic expansion under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping 邓小平. Higher education has been able to undergo long-standing reforms to develop into a system that is an integral part of global education and that at the same time represents the needs of the Chinese for training a qualified young generation. However, the reforms do not function in isolation but are intermingled with political, economic, and cultural reforms. As a matter of fact, many Chinese people see educational reforms, along with health care reforms, as unsuccessful, and this perspective is acknowledged by the government. Further reforms have been called for.

1.2.2 The National College Entrance Examination

1977 was a remarkable year in the modern history of Chinese higher education during which the government restored the National College Entrance Examination, gaokao 高考, and admitted students to universities based on their gaokao exam scores. In fact, higher education institutions revived training students in 1972 when Deng Xiaoping temporarily regained power. Nonetheless, students were admitted to universities not by testing but through a referral routine based on candidates’ political persuasion. The nationwide standard exams taken in 1977 and several months later in 1978, which were the first to occur after the Cultural Revolution, allowed high school graduates and the graduates during the Cultural Revolution to compete for entrance to college and opened a fair, wide door to young people who would otherwise be sent to rural fields to work as peasants. Since then “77–78” has become an expression to describe those who entered colleges during these two years, a term for elites who are today dominating the research and government domains, including the current Prime Minister Li Keqiang 李克强. Their glory illustrates the beginning of a higher education renaissance in modern China after a long period of political chaos.

The gaokao is a grueling, multiday test that includes several subjects, such as Chinese, mathematics, one foreign language, and political science. Students picking a science concentration are required to add physics, chemistry, and biology, whereas students selecting the humanities and a social science concentration need to take history and geography. The subjects tested have changed over the years and across regions. For example, foreign language was an optional subject for the first years of the gaokao but later became a mandatory subject. Regional differences of the test are province- based. In 1977 each province created its own testing questions; this system was replaced by a national standardized test in the following years but returned to provincial control in the mid-1980s in many places. Recently, some provinces exercised a 3 + 1 plan (or some variation) that asks students to take Chinese, mathematics, and one foreign language (usually English) as general subjects and that blends other subjects into either a science-focused program or a humanities-focused one.

In response to the fact that college degrees have become the primary, if not the only, ticket to decent employment and career promotion, parents explore every available resource to send their children to the best high schools. The gaokao and test preparations have been touchy topics and are inevitable for families with teenagers. Successful gaokao stories are circulated, helping to stimulate students to work hard on preparing for the test. Gaokao testing guides and preparation materials are abundant in the marketplace. As a result, a pedagogical scheme tailoring test preparation is promptly developed and cram programs are formed to train those who failed a previous gaokao test.

The annual gaokao test usually takes place in early June. It is such an important event that local governments direct valuable resources, including the force of policy, to ensure a smooth and secure exam. Public transportation is planned in advance to detour traffic and give student travel priority. Sources of noise that may distract testing are removed temporarily. At the testing spots, metal detectors, monitoring screens, and even drones in extreme cases are operated to prevent possible cheating. Typically, while students are sitting in well-organized and tightly managed classrooms, their parents, in hundreds, crowd in front of locked schools, as anxious as the test takers.

Although generally students are admitted to colleges solely based on their gaokao test scores, there are several exceptions, for example, those with an ethnic minority background receive some bonus points, and so do those with athletic or artistic talents. A perceived bias relates to regional differences in the number of admissions. Universities follow an admission allocation standard, set by the Ministry of Education, which asks them to admit different numbers of students across provinces. Peking University, as an example, accepted 61 students in costal China’s Shandong Province from a total of 497,684 test takers (an admission rate of 0.012%) in 2012, yet in the same year took 614 new students in Beijing, where its campus is situated, from 73,000 applications (an admission rate of 0.84%, which is 70 times the rate of the former).23 Considering that almost all universities have such a prejudiced geographic quota and that most of them, particularly the prestigious ones, cluster in large cities like Beijing and Shanghai, an admission allocation obviously works against disadvantaged regions. This quota tradition was initially created because universities needed to provide dormitories for all their students, while accepting more local commuters increased the enrollment of students without the need to provide additional residential facilities. Years later, even with such residence requirements phased out, the geographic difference in admission is still in practice.

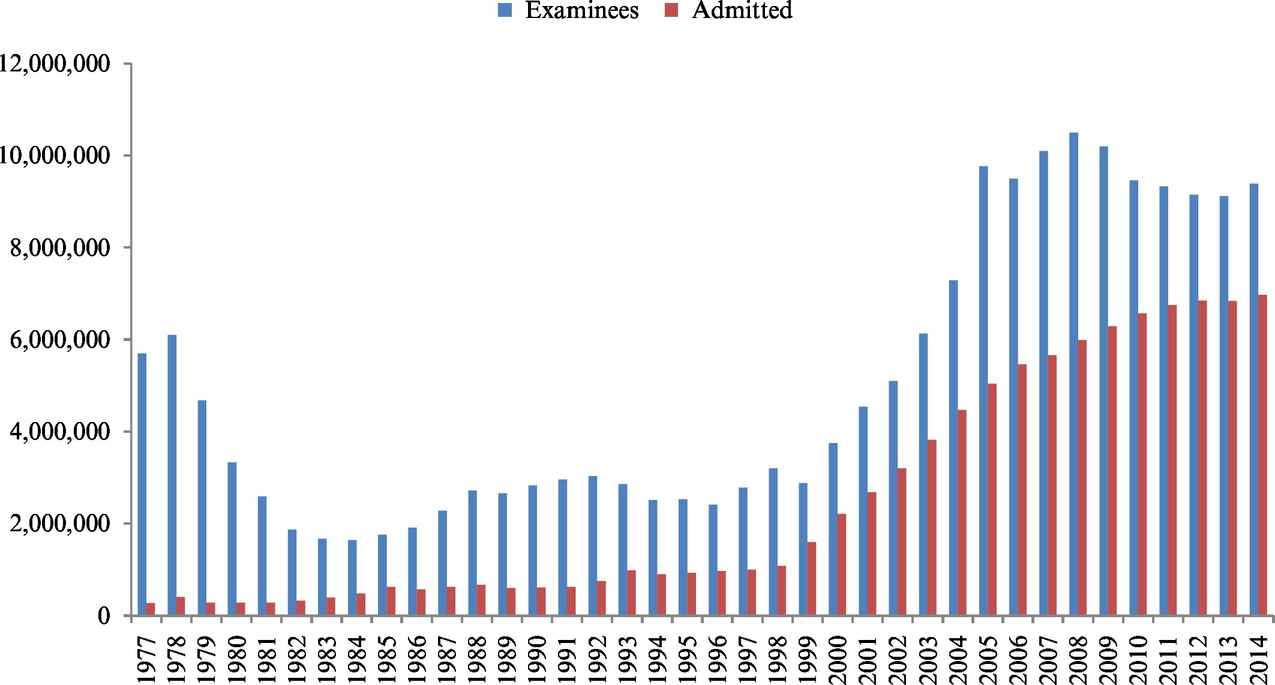

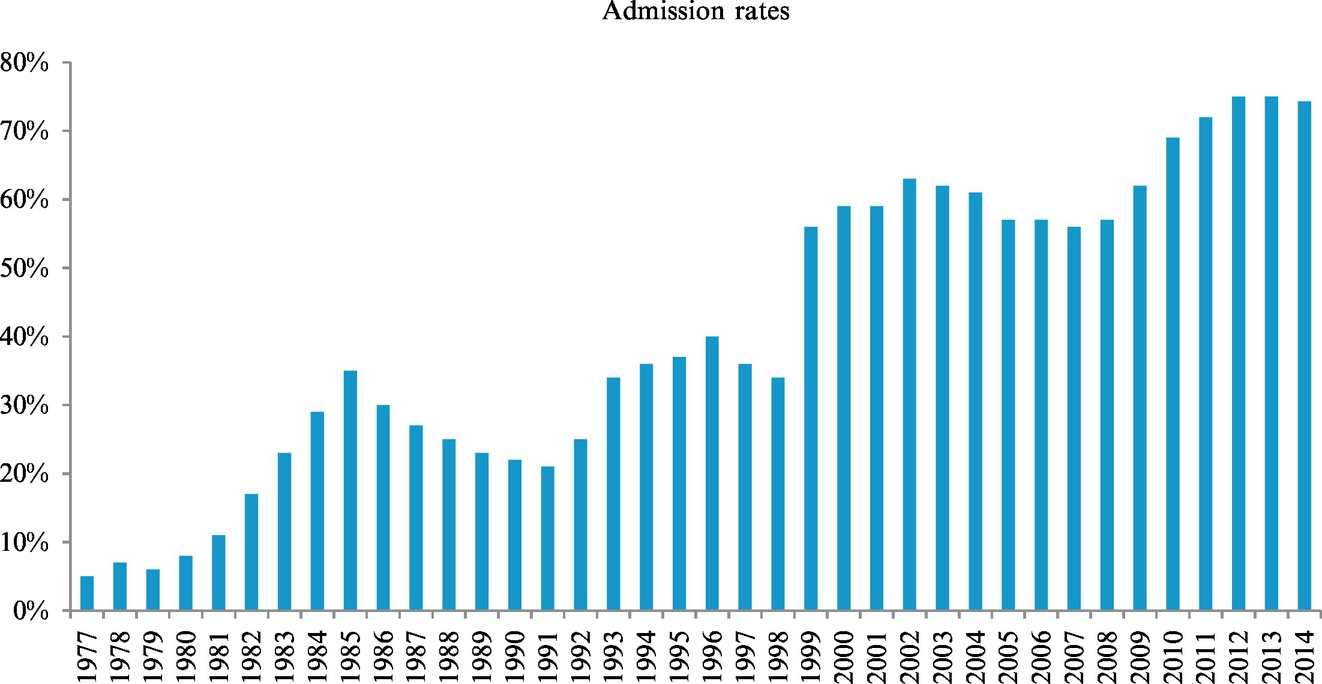

If the 77–78 students, with an admission rate of only around 5%, could easily leave a legacy of success, the students admitted in recent years, with an admission rate of more than 75% nationwide, are no longer able to generate the same excitement.24 Fig. 1.1 shows that the number of students taking the gaokao test fluctuates from year to year with a relatively steady increase in the new millennium. However, this is not comparable to the number of admitted students, which shows a much steeper increase at the same time, as shown in Fig. 1.2. This discrepancy is well demonstrated by the changing trend of the admission rates over time: it has become much easier to gain entry to colleges year by year.

Other changes around the new millennium are also substantial. The gaokao is not the only option for high school students, many of whom take other college admission exams organized by foreign nations, notably the SAT and ACT by the United States, and attend universities overseas. As of 2014 as many as 459,800 Chinese students were pursuing their college degrees outside China, which is equivalent to almost half of the total population of the gaokao takers (939,000) in the same year.25 In the United States students from China make up 31% of all international students.26 Furthermore, even for those who have already taken the gaokao exams, seeking higher education in other countries may be a normal decision. In response to the rapidly increasing number of Chinese applications, some institutions in the West have now accepted gaokao scores in undergraduate admissions, such as the University of San Francisco in the United States and several Australian universities, including the University of Sydney.

1.2.2.1 Remarks

In spite of the fact that the gaokao has experienced tremendous changes over the past three decades in its subject selection and content control, an urban- rural divide has consistently favored resource-rich cities over underprivileged rural areas. Under China’s strict residency constraints (hukou 户口), students of varying birthplaces do not share the same access to education. Similarly, even if the number of college admissions has soared over the years, a geographic divide of provinces has persistently victimized those whose family registrations are bound to some areas while rewarding those whose residencies belong to other regions. The current trend of studying overseas and the high rate of college admissions have helped lessen these divides to some extent, yet created other types of unfairness, for example, opportunities to enter elite universities.

1.2.3 College Students

Upon entering universities, students find a lower stress environment for study than in high schools where the gaokao is a tangible burden. The college life of four years for students is relatively laid-back when their residence is supplied by the university and a job is assigned at graduation. Before 1994 higher educational training was free of charge, including free tuition and residence, and students even expected to get a small amount of funding from their home university, based on the income level of their parents, to defray food and other regular expenses. Students seeking master’s and doctoral degrees had competitive monthly stipends or were supported by scholarships.

Students in the same department and the same year of entry are organized into classes for the purposes of course selections, extramural activities, and dormitory arrangements throughout their college life. A student with management skills is assigned to be the commander of a class and is assisted by several other selected students of the same class, each of whom is responsible for one particular area, such as study, activity, and physical exercise. A junior faculty member serves as the counselor of each class. At the departmental and campus levels, a student council president is assigned to help manage large groups of students. This organization allows students to build long-term relationships with each other and with faculty, and is easy for the school administration to manage.

In the past four decades since the first gaokao in 1977, college students have experienced changes in their attitudes toward study, for example, from viewing study as a path to knowledge to treating it as a necessary step to the next target, whether the next target is employment or further education. Students in the hard sciences generally have heavier workloads than students in the soft sciences, and graduate students at the master’s or doctoral levels are relatively busier because they need to balance between study and work for their advisors. Another visible change is the decreased length of study terms from six days a week to five days a week and from more than a five-month semester to more than a four-month semester with additional weeklong breaks for the International Labor Day in early May and China’s National Day in early October.

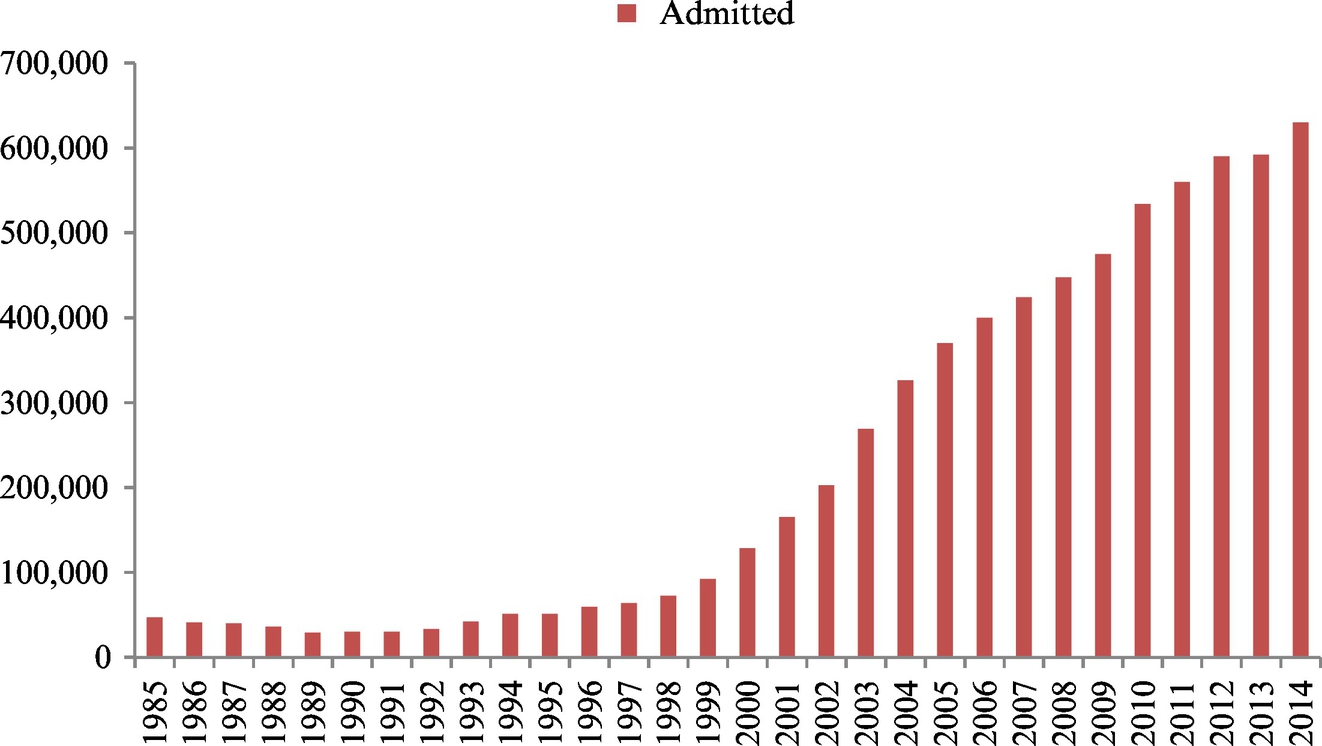

Other major changes have also occurred since the mid-1990s to form the present picture of higher education, for example, tuition and dormitories are no longer free and have become more and more expensive, and job placement upon graduation is no longer guaranteed because of the ever- increasing number of college admissions. The first change has a negative impact on students who are from low-income families and rural areas, while the second change affects the development of scholarly communication in China. According to official statistics, the number of students leaving colleges with a degree has climbed each year, for example, from 1.15 million in 2001 to 7.27 million in 2014; and the number of students without a job offer at graduation has also skyrocketed, for example, from 0.34 million in 2001 to 2.3 million in 2014.27 In other words, as of 2014 the number of unemployed college graduates was higher than the total population of undergraduate and graduate students combined in the United Kingdom28 (Figs. 1.3 and 1.4). Having faced such a tough market, many college graduates decide to continue studying for a master’s degree and then for the same reason for a doctoral degree, which has dramatically expanded the workforce of, and consequently competition among, future scholars (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1

Comparison of doctoral recipients from Chinese and US universities by year25,29

| Year | China | US |

| 2000 | 9409 | 41,372 |

| 2001 | 12,867 | 40,744 |

| 2002 | 14,638 | 40,031 |

| 2003 | 18,806 | 40,766 |

| 2004 | 23,446 | 42,123 |

| 2005 | 27,677 | 43,385 |

| 2006 | 36,247 | 45,622 |

| 2007 | 41,464 | 48,133 |

| 2008 | 43,759 | 48,778 |

| 2009 | 46,616 | 49,554 |

| 2010 | 48,987 | 48,032 |

| 2011 | 50,289 | 48,903 |

| 2012 | 51,713 | 50,977 |

| 2013 | 53,139 | 52,760 |

Not only has the inflated population of doctoral students made China the top country in the world for conferring doctorates, but it also has created problems to higher education regarding the quality training necessary for preparing competent scholars. According to official statistics, as of 2000 the number of doctoral recipients from Chinese universities was only one-fifth of those from US universities, whereas only 10 years later, China started surpassing the United States. These numbers do not include Chinese students receiving doctoral training in the latter country as well as other countries. Since the past decade, China has remained the largest source country for international students receiving doctoral degrees in the United States.29,30 Compared to the United States where around 250 higher educational institutions are eligible to confer doctoral degrees, China has more than 360 such institutions.

The quality of doctoral training has been extensively questioned both inside and outside academia. A survey finds that nearly half of academic advisors supervised more than seven students with the highest ratio being 1:47, and about 13% of students were unable to talk to their advisors every month.31 Several factors contribute to this condition: (1) professors are awarded financially based on the number of students supervised, (2) professors are pressured to seek grants and therefore do not have time to tutor their advisees, and (3) universities implement a hard-entry-but-easy-leave policy that all students can obtain a doctoral degree if they want to. Another notable practice has been that government officials and rich businesspersons are fond of being called “Dr.” and pack graduate schools without spending real time there studying.32 To a degree universities are trading diplomas for power and wealth, hence deflating the value of a doctoral education. Still, I have not yet discussed the quality of university professors and of pedagogical approaches and instructional techniques.

It typically takes a student four years to earn a bachelor’s degree, two to three years to earn a master’s degree, and two to three more years to receive a doctorate. At every level of these studies, a student needs to learn at least one foreign language and to study the Marxist theory. Both master’s and doctoral students must pass required oral/written examinations and defend their theses/dissertations. A graduate at all levels receives a degree certificate and a graduation diploma separately. Graduating from a university does not guarantee a degree certificate, because the requirements for the graduation diploma are lower than those for the degree certificate. Though there are national standards regarding degree requisites, individual institutions may have their own policies that are slightly different in terms of the number of credits to be completed.

1.2.3.1 Remarks

On the one hand, the body of college students, including both undergraduate and graduate students, continues to swell and has reached a stage in which an overwhelming majority of young people can now receive a higher education. On the other hand, higher educational institutions are not equipped with necessary perceptions, structure, personnel, and facilities to handle these changes. This quantity-quality contradiction has somewhat impeded healthy advancement in the higher educational tradition and the scholarly communication process and will continue to be a problem that demands further reform. The lack of quality control over doctoral training specifically leaves a question mark on the research conduct of the future scholars.

1.2.4 University Professors

A chronological change of faculty profiles over the past several decades is characterized by the following patterns.

| 1970s–80s | Universities were intellectually controlled by those who graduated from colleges before the Cultural Revolution. Typically, they were trained in the home country with a bachelor’s or master’s degree because doctorates were rarely conferred then. Much of their careers were spent on participating in political events required by the government rather than academic pursuits so that their scholarly achievements were rather minimal, particularly for those in the hard science fields. |

| 1980s–90s | The new generation of the 77–78 students and graduates for a few years afterward dominated research and instruction in higher educational institutions. Because of the Cultural Revolution’s destructive effect on education, there was a gap of generations between scholars of the previous period and the new generation of the 77–78 graduates. The so-called gongnongbin 工农兵 students, who entered college between 1972 and 1977 without taking the gaokao test, were quickly marginalized by society, leaving wide spaces for the 77–78 people to advance quickly. |

| 1990s–2000s | Foreign trained scholars returned home, many of whom were also the 77–78 fellows but went on to obtain doctoral degrees overseas. The government provided attractive incentives as an internationalization effort to lure them because they were considered to be able to bring back distinct theories and methods from the West, while at the same time understanding the Chinese tradition. Several government programs, such as the Changjiang Scholars program 长江学者 and the Hundred-Talents program 百人计划, played an important role in drawing selected scholars. |

| 2000s–Present | This is a period of diversification when universities have an assemblage of faculty trained overseas and locally. The former are acquainted with the Western style of research methodology, while the latter understand how to follow local standards. Despite that both groups blame the other for monopolizing resources, they work together to make contributions to science and to train the future generations of scholars. Pressures on resource availability have been tremendous for the young generations. |

A hierarchical faculty structure usually consists of an assistant lecturer 助教, a lecturer讲师, an associate professor, and a full professor. The first is the lowest rank and was originally designed for those who upon graduation became a university instructor, but today that role is frequently taken by doctoral students. The full professor rank contains more subranks than any other level of faculty, for example, the master’s supervising professor 硕导 and the doctorate supervising professor 博导. A master’s supervising professor is not eligible to advise doctoral students, while a doctorate supervising professor can direct both doctoral and master’s students. The professor rank may also include specially appointed professors, joint professors, endowed professors, guest professors, and distinguished professors. The highest honor of a full professor is the academician 院士 who is nationally selected to be the fellow of one of the academies (namely, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Engineering) and is compensated by the government. Both academies have presently elected a limited number of foreign scholars, including I.M. Pei, an internationally renowned Chinese American architect. In order to advance to a higher level in the ranking, a candidate must fulfill corresponding requirements for research and teaching and pass a foreign language proficiency test required since 1999 and a computer proficiency test required since 2002.

There has been a complexity of strains on university faculty who are stratified in battling for limited resources open to higher education. Job-related stress has resulted in a profound impact on the behavior and performance of scholars in teaching, research, and publishing. Corresponding to the temporal changes of the faculty profiles, the stress has varying characteristics with obvious political and cultural traits, and also differing between dissimilar types of institutions—for example, research-oriented ones and instruction-focused ones—and among different subject areas, for example, engineering versus social science.

Because of the meager investment in education during the Cultural Revolution, students who graduated in the first years of the gaokao shared with their distant predecessors who graduated before the Cultural Revolution in promptly taking control over the majority of the educational resources. With a series of government actions for bringing higher education up to an international caliber, imported scholars were enthusiastically introduced and allowed to seize their portions of the resources. Together, these groups have crafted rules to regulate the career of younger generations.

Although institutions create their own policies to assess the performance of their employees, there is a commonality of interests among the institutions to pressure faculty to produce numerous high-quality publications, to bring in grant money, to publish manuscripts (mainly for social science and humanities), and to obtain patents (primarily for applied science). Most of the policies are copied from universities in the West, but with even stricter requirements, setting specific criteria for use in faculty promotion. Taking publication as an example, a fixed number of journal articles per year is the basic requirement, and the journals need to be indexed by recognizable international agencies such as the Science Citation Index (SCI), the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI), and the Engineering Index (EI).

The young generations of university faculty and research institution scholars are among the most worrying groups who graduate from a relaxing environment with little, if any, quality doctoral training but are forced to compete with national and international peers at work. As of 2014 there were a total of 884,000 professors under the age of 40, comprising approximately 63.3% of all university faculty in the country.25 They are considered too inexperienced for major research grants, and in many cases they must work for senior colleagues under their projects, or they have to take on additional teaching loads to add to their low base salary.

1.2.4.1 Remarks

Senior and junior ranks of higher institutional faculty represent two conflicting entities that possess discrete accesses and controls over educational resources with regard to power in academic and administrative promotions as well as research fund distributions. Because of the unique history of modern higher education in China, the former group readily grasped the power after they entered academia and left their successors struggling for survival and growth. At the same time, two other contradictory groups are in the fight for resources, namely, those natively trained and those from foreign countries. Such dynamics of faculty profiles have contributed largely to an unbalanced, and to some extent unhealthy, development of scholarly communication in China, a topic that I will describe in the following chapters.

1.2.5 Higher Educational Institutions

Although passing the gaokao test and receiving an offer for admission to college are no longer distant goals for many students, getting into top-ranked institutions still requires a great deal of effort in terms of test preparation. A diploma from a top institution can assure a brighter employment future. In May 1998 the government launched a “985” project aiming at developing world-class universities. The project presently includes as many as 39 institutions. Another project, the “211” project, named after the plan to develop 100 + institutions in the 21st century, supports 118 institutions nationwide that overlap with those on the “985” list. Becoming a “985” or “211” student today is as revered as it was to obtain an admission to a regular college decades ago.

Higher educational institutions have been firmly stratified. At the top of the spectrum are the “985” and “211” universities, which are followed by regular first-tier universities, and then by the second-tier and third-tier ones. With reference to the type of institutions, the list is rather long, including general-purpose universities, specialized schools and colleges, vocational universities, adult (informal) higher education, administrative colleges, employee’s colleges, radio and television universities, and so on. As of 2014, China had 2542 colleges and universities (not including independent colleges), 2246 of which were regular institutions (including 444 nonpublic ones) and 296 of which were for adult education (including one nonpublic institution).36

The current topography of higher educational institutions is the result of the continuous reforms from 1977, of which the most substantial reform was the amalgamation of institutions in the early 1990s and 2000s that made general universities more comprehensive and that merged those of similar or related specializations. For example, a total of 612 higher education institutions were consolidated into as few as 250 institutions. During the reform, the authorities wanted to implement joint administrations into the institutional structure so that universities were no longer owned and operated by various central industry ministries. Instead, the administrative power of institutions would be shared by both the national and local governments with the latter having the main control. This two-tiered administrative arrangement is the current norm.

Under recent government initiatives, useful educational resources lean toward selected top schools in order to increase their competitiveness to foreign universities in the global races. In the first, second, and third phases of the “211” project, the government invested as much as ¥20 billion CNY, which is about $3 billion USD, while the “985” project cost the government ¥28.5 billion CNY (about $4.3 billion USD) in its first and second phases.39 In addition to these projects, China also initiated a “2011” plan to sponsor major research projects, and around 83% of the funds were given to the “211” institutions. The resonant supports have made elite universities sustainable financially and academically, while leaving other institutions in a deteriorated situation. The latter’s disadvantage makes it very difficult to compete with the former for funding and personnel. In order to survive, many second-class schools must raise students’ tuitions and reduce payments to employees, hence further degrading their ability to attract good students and faculty. When the job market candidly marks their preference to graduates of the top schools, other institutions clearly feel the pain.

A list of budgetary numbers for some top universities reveals that the Chinese government has indeed invested heavily in higher education, and the investments are comparable to recognized universities in the United States and United Kingdom (Table 1.2). It is worth noting that this list is for reference purposes and does not take other factors into consideration, such as differences in living index and faculty size. With the sufficient support, several Chinese universities have started making their name on various ranking lists of world universities. For instance, both Peking and Tsinghua Universities have been placed among the 50 best universities by the Times Higher Education several years in a row,41 while Peking University was ranked as number 41 by the U.S. News and World Report in its best global universities category in 2016.42

Table 1.2

Comparison of 2014 budgets between selected top Chinese universities and UK and US universities.40 Numbers converted to US dollars in billions

| Institution (China) | Revenue | Expenditure | Institution (Foreign) | Revenue | Expenditure |

| Tsinghua University | 1.93 | 1.81 | Cornell University (USA) | 3.60 | 3.60 |

| Zhejiang University | 1.71 | 1.11 | Cambridge University (UK) | 2.37 | 2.37 |

| Peking University | 1.34 | 1.36 | UC Berkeley (USA) | 2.35 | 2.14 |

| Shanghai Jiaotong University | 1.26 | 1.13 | Oxford University (UK) | 1.85 | 1.80 |

| Fudan University | 0.73 | 0.69 | Princeton University (USA) | 1.58 | 1.58 |

| Wuhan University | 0.81 | 0.70 | University of Iowa (USA) | 0.68 | 0.53 |

| Jilin University | 0.81 | 0.67 | University of Idaho (USA) | 0.45 | 0.45 |

Similar competitions exist among the best universities, though this less possible among the lower-tier institutions because they are mostly location-bound. Stories of battling for the gaokao champions in both the science concentrations and the social science/humanities concentrations between Peking University and Tsinghua University make headlines each year. During the 2015 admissions both institutions used social media to blame each other for using dishonest strategies. In recent years many Hong Kong universities entered the competitions by providing more attractive scholarships, but of late have retreated from the market because of the lack in student preference for them. From 2005 to 2014, for example, of the 21 gaokao champions in Hubei Province, 13 attended Peking University and eight accepted Tsinghua’s offer, whereas Hong Kong universities collected a total of 10 champions from the entire mainland.

The structural chart in Fig. 1.6 represents the current formation of higher education, which is the result of several cycles of educational reforms in the past four decades. For a long time, every central ministry and council had its own institution(s), jointly managed by the Ministry of Education. After the most recent reforms, local governments at the provincial and municipal levels have taken the responsibility financially and administratively, even if the ministry still plays a central role in creating and implementing important educational policies and regulations, coordinating educational initiatives and programs, and directly managing a group of the most selective seventy-five institutions. All public universities, except the “211” and “985” institutions, are under the control of the provincial or municipal governments through their educational commissions.

The State Council has an Academic Degrees Committee to study, craft, and amend degree regulations, supervise implementation of the regulations, guide the appraisals of academic disciplines, monitor degree-related exchange projects with foreign countries, undertake institutional accreditations, and participate in strengthening educational qualities. The routine work of this committee is being run by the Ministry of Education although its chair is assigned by the State Council and its bureaucratic structure is at the same level as the ministry. Top scholars and education specialists are regularly consulted about the creation and improvement of educational regulations.

It is noteworthy to mention the various research-based academies, some of which have their own universities to train students at the bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral levels. Bureaucratically, these academies belong to the State Council, the same level as the Ministry of Education. Each academy has its provincial branches and employs a numerous scholars whose major responsibility is research and whose contributions to scholarship are enormous. Here is a snapshot of the academies.

• Chinese Academy of Sciences: It has six divisions (mathematics–physics, chemistry, life science-medical science, geoscience, information technological science, and technologies), 12 provincial branches, 104 research institutes, two presses, and hundreds of laboratories and centers. It also manages three degree-granting higher educational institutions, one of which, the University of Science and Technology of China, is a top-ranked university in the country. As of 2015 the academy employed more than 50,000 scientists nationwide.43

• Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: As the leading think tank in China, it also has six divisions (philosophy and literature, history, economics, social, political, and legal studies, international studies, and Marxist studies), 40 research institutes, a graduate school, and hundreds of research centers. The graduate school is authorized to train students at the master’s and doctoral levels with a total of 3100 students as of 2015. As of 2015 the academy employed about 2200 scholars.44

• Chinese Academy of Engineering: Unlike the former two academies, this academy consists of only 611 individual academicians who are selected from scholars in all engineering fields based on their scholarly merits. The academy functions to develop policies, evaluate scientific projects, promote collaborations, facilitate scholarly exchanges, provide consultations, and overlook ethical practices.45

Private institutions were allowed in the 1980s and have expanded greatly since then, particularly in the past decade when foreign universities entered the country. Among others, New York University has a campus in Shanghai,46 and Duke University has a Kunshan campus in Jiangsu Province.47 The Ministry of Education now grants a permit only to collaborative efforts between a Chinese institution and a foreign one, so these two US universities each have a native collaborator. More such efforts are on the level of individual programs, such as two universities’ joint business school or engineering school. Locally, funds from individuals, nonprofit organizations, businesses, and community groups have helped develop privately run and owned higher institutions. Some of the nongovernmental institutions confer an academic degree recognized by the Chinese government through its self-study examinations, while others concentrate on training students on marketable skills. More discussions on international joint efforts are available in Chapter 5.

1.2.5.1 Remarks

The series of educational reforms have made big institutions even bigger, which is exactly the purpose of the reforms because the policy makers intended to make an efficient use of the available resources in order to create world-class universities. However, many small, regional institutions have been more deprived, which is not the purpose of the reforms, yet an inexorable byproduct. Both possess not only an asymmetrical access to educational resources but also unequal competition in student employment and faculty career development. Many of the small, regional institutions have implemented a similar standard of performance assessment toward faculty’s research as that of the big institutions. At the same time, regional universities assign their faculty heavy teaching loads without providing necessary support. Consequently, the gap between affluences and poverties in higher education is very visible and will become even wider if effective policies are not created in the near future.

1.3 Conclusion

One of the main purposes of higher education is to train students to be future scholars in a well-structured learning environment with carefully designed pedagogies. The competences and enthusiasm of faculty, who themselves are scholars as well, in providing capable and passionate training are key to reaching the goal. In Chinese history higher education focused on a curriculum consisting mainly of Chinese classics and on developing a sense of moral sensitivity and duty toward people, society, and the state. Since the Western system of education was introduced in the country in the late 19th century, China’s higher education has experienced extraordinary changes in tandem with concurrent political, economic, and cultural forms. The extended periods of military combat and economic suffering have hampered normal progress of the enterprise, while the short intervals of peace have left too little time for policy makers, administrators, and educators to complete systematic and needed transformations.

The time after the Cultural Revolution is the heyday of higher education in China, during which it has benefited from remarkably long-term economic growth. With a series of reforms, for example, education is now a ubiquitous business in which an overwhelming majority of high school graduates can expect to receive higher education training and obtain a college degree. By the same token, China has become a top nation in terms of conferring doctorates and the number of its universities. The country now employs a sizable number of scholars who are making numerous contributions to scholarship.

This rapid advancement in higher education is accompanied by inevitable imperfections and mistakes. Several educational reforms indicate that the communist leaders have modified Chairman Mao’s ideology of egalitarianism and assembled available resources to support a few selected elite institutions so as to build world-class universities, because the development in the economy is in no way proportional to that in education. The imbalance between demands and investments has caused unfairness among students of dissimilar origins, tensions among varying groups of professors, and competition among differently ranked higher educational institutions. Another obvious conflict between quantity of educational products and quality of academic training has started harming, and will continue affecting, the healthy progress of higher education, and thus the excellence of scholarly communication. The Chinese have noticed these issues and are rather optimistic about the solutions: “Problems produced by reforms can only be resolved by further reforms.”