CHAPTER FIVE

Theory into Practice: Thirteen Expressions of Passion in Selling

“An ounce of action is worth a ton of theory.”

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

“In theory there is no difference between

theory and practice. In practice there is.”

—YOGI BERRA

AS MENTIONED IN CHAPTER 1, the most successful interactions between salespeople and their affluent prospects bring all three passions together:

• A salesperson with a sincere love for what he or she does

• A prospect who is pursuing a sincere interest

• A product with transcendent properties

Two people arrive, of their own free will, in an environment of their mutual choosing. The shared interests are apparent. Rapport is established quickly and easily. The meeting of minds in terms of needs and wants is of primary importance; price considerations are secondary, at best. The transaction satisfies and furthers the interests of all parties—buyer, seller, and manufacturer.

The three passions do not always come together so effortlessly, however. This chapter explores thirteen straightforward, authentic ways to leverage the passions inherent in a sales situation. For each, there are exercises that will help you put these ideas into action and help close sales.

1. Express the love of your job.

2. Tell detail-rich stories.

3. Discover a shared pursuit.

4. Give the docent’s tour.

5. Understand their ultimate passion: family.

6. Satisfy the passion du jour: value.

7. Use the language of passion.

8. Understand that reliability is “the new trust.”

9. Create a ritual of celebration.

10. Communicate a compelling brand promise.

11. Hone a compelling elevator pitch.

12. Ask passion-based questions.

13. Sell to happiness.

EXPRESSION 1:

EXPRESS THE LOVE OF YOUR JOB

“When any fit of gloominess, or perversion of mind, lays

hold upon you, make it a rule not to publish it by complaints.”

—SAMUEL JOHNSON

“Choose a job you love and you will never have to work

a day in your life.”

—CONFUCIUS

Of the hundreds of ways for a salesperson to turn off a prospect, perhaps the easiest is simply this: to complain. About anything. Your job, your hours, your commission—or lack thereof. The bureaucracy that holds you back. The boss who doesn’t appreciate or understand you. The seemingly endless recession. The product or service you sell can be a source of so many complaints, but the most common one is usually that it costs too much: “If only the powers that be would lower the price, I could sell the crap out of X.”

No job is perfect. No day is without disappointment or distraction. It’s normal to feel frustration. It’s just not wise to express that frustration to your customers. Samuel Johnson, quoted above on the wisdom of withholding complaints, concluded: “The usual fortune of complaint is to excite contempt more than pity.” He was right. Prospects have their own problems. They are working with you to help solve those problems. Or prevent them. Or, at the very least, put them out of their minds for a little bit while they focus on something more pleasant. Prospects aren’t there to hear about your problems. In fact, what they really want to hear is just the opposite. They want to hear about how much you love your job. As one of our wealthy research participants put it:

“For me, the ideal salesperson is somebody who loves their job. I want to make their day happy, and I want them to make my day happy. You can usually see it and feel it, right away, when somebody really loves what they’re doing. . . . When I sense that, I’ll spend! I will. I just want to say to them: ‘I’m so happy that you’re happy!’ I’m going to come back and I’m going to use that salesperson again and again and again.”

Our research has shown, and our sales training work has confirmed, that simply declaring a love and an enthusiasm for your job can be a powerful rapport builder. Indeed, one of our training programs suggested that this technique alone could generate as much as a 20 percent increase in average revenue per customer.

The psychological dynamics behind this simple technique are surprisingly complex. The fact is that the class differences between a member of the financial elite and the typical salesperson are fully apparent to both, and it can be cause for discomfort for both. The customer typically believes in stealth wealth, not simply to avoid being targeted but also because it is authentically consistent with the values of modesty and humility so prominent in their middle-class upbringing. They recognize that this salesperson is likely “not of the class,” and this hampers the customer’s willingness to disclose both his or her purchasing motivations and a personal evaluation of the product or service at hand.

You, as salesperson, can imagine how a customer who fears being judged as shallow, wasteful, and pretentious might be hesitant to say something like, “I’d like to get a Cartier Pasha watch to replace the Bulgari Diagono watch I lost while sailing in the Caribbean. I’d like to pay around $5,000, but I don’t want it to look too blingy—know what I mean?” On the other side, as salesperson, you can also feel uncomfortable, particularly if you are relatively new to working with the wealthy. This can be an intimidating, nerve-racking experience. You’re apt to fear coming across as not sufficiently knowledgeable about the products, and/or unable to understand the needs and lifestyles of the wealthy customer.

Expressing your love of your job can be a potent way for you to ease that unspoken and potentially disruptive class divide. As we have seen, in most cases today’s wealthy individuals did not set out to accumulate tremendous wealth. Instead, most are entrepreneurs and business executives who pursued a passion, and wealth was an almost accidental side effect of their hard work and eventual success. By expressing a love of your job, you make both you and the customer feel more comfortable. It creates a powerful shared connection: The customer is no longer a wealthy prospect and you are no longer an intimidated salesperson; you are two individuals who pursue their passions.

Here’s an important caveat: Expressing your love of your job must be sincere. Any lack of authenticity will be patently obvious. Today’s financially successful have fine-tuned their BS detectors. Successful entrepreneurs and senior executives have heard many sales pitches; indeed, part of their professional success has come from their ability to size up situations, to evaluate sincerity, and to gauge the ability of someone to deliver on promises.

EXERCISES

List five things you love about:

• Your job

• Your customers

• The products or services you sell

Practice telling stories that:

• Demonstrate your passion for your work

• Describe your most satisfying interactions with customers

• Illustrate your sincere interest in the products or services you sell

EXPRESSION 2:

TELL DETAIL-RICH STORIES

“It’s the little details that are vital.

Little things make big things happen.”

—JOHN WOODEN

“Storytelling is an ancient and honorable act.

An essential role to play in the community or tribe.”

—RUSSELL BANKS

These days, talk is cheap. Sales pitches are easily discounted and routinely dismissed. Today’s sales environment is fraught with distrust. Persuasion through advertising has become tremendously challenging, and the medium itself has largely come to focus on simply building awareness as a result.

The question becomes: How do you enhance believability in an environment of distrust? Product demonstrations can play a role, as can testimonials. But in selling to the affluent, perhaps the most powerful verbal tool in the salesperson’s arsenal is telling a great story, rich in detail.

We’ve all heard the saying “The devil is in the details,” and we can appreciate its message that the execution of lofty plans is more challenging than the creation of those plans. But perhaps even more telling is the quote upon which the German proverb is believed to be based, generally attributed to French novelist Gustave Flaubert: “The good God is in the detail.” On the whole, we’re inclined to side with Flaubert. Details are extremely powerful, almost transcendent.

Chapter 4 explored many examples of how sublime details are what separate true luxury products from their mainstream competitors. Details of history and provenance. Details of exquisitely sourced and mixed materials. Details of engineering and craftsmanship. Of clientele and of meaning.

Here we discuss the power of details, which is twofold. First, details make stories engaging, a fact that writers over the centuries have understood well. As Vladimir Nabokov counseled, “Caress the detail, the divine detail.” Details engage attention, arouse the senses, and inflame the emotions, for good and ill; as English novelist Ruth Rendell put it, “The knives of jealousy are honed on details.” Details cut through the attention filters that people put up to deal with the barrage of advertising images and sales pitches that bombard them. They perk up. They tune in. They start listening more intently, and that’s precisely what you, as a salesperson, need.

Second, details not only engage the attention, they also inherently make a story more believable and make the salesperson who provides them more credible. In contrast, descriptive terms and vague adjectives—like luxurious or prestigious—gloss over details and hide a lack of specific knowledge.

Consider two hypothetical salespeople for the Italian firearms company Beretta. Salesperson A, who lacks detailed knowledge about the company and its products and uses vague descriptions to cover up that lack of knowledge, explains that Beretta is an Italian company with a long history of making excellent firearms for buyers around the world. Salesperson B, in contrast, explains that Beretta is actually the oldest corporation in the world, with its first transaction taking place in Venice in 1526. Today, after nearly 500 years, Beretta is still run by a direct descendent of the founder, and it is recognized as the finest manufacturer of firearms in the world, with customers including the U.S. Army, the Marine Corps, and police departments around the world.

Think about the tremendous differences in these few simple sentences from two different salespeople. Salesperson B gave us a considerably richer story. Venice, not Italy. The “oldest corporation in the world” founded in 1526, not simply a “long history.” Their customers include the U.S. Army and Marine Corps, not just “buyers around the world.” Excellence is not simply stated but is implicit in details, such as 500 years of nearly continuous management by a single family and its reputation as the finest manufacturer of firearms in the world. Which story grabs your attention? Which one convinces you of the salesperson’s superior product knowledge? From which salesperson are you more likely to buy? Details provide the proof points, demonstrating both the quality of the brand and the quality of the salesperson.

EXERCISE

Craft and practice detail-rich stories about:

• The origin and founders of the company you represent

• The history of the brands you offer

• The provenance of specific products and offerings

• How high-end offerings in your category differ from mainstream offerings

• Spectacular, mutually rewarding customer service (preferably by you)

• Tremendous customer loyalty

• How your company treats customers and employees extremely well

• How working for your company is different from working at other jobs

EXPRESSION 3:

DISCOVER A SHARED PURSUIT

“Shared joys make a friend, not shared sufferings.”

—FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

In Chapter 2, we explored the long history of marginally successful research on top sales performers. It’s worth revisiting one of those less than dramatic predictors: the similarity between the salesperson and the prospect. In the 1960s, it was a topic of considerable research. Similarity on dimensions as mundane as age, height, product preferences, ethnicity, and even smoking were mildly associated with greater rapport and stronger sales.

There’s no denying the phenomenon: People like to work with people similar to themselves. It’s just that there’s a limit to it. No matter how much emotional comfort is provided by similarities, prospects won’t buy from a salesperson who doesn’t know what he is doing, or if the value proposition isn’t right, or for any of dozens of other reasons. Yet, there’s no denying the connection and rapport-building power of discovered similarities.

Much of the research from the 1960s focused on similarities along demographic dimensions. Today, we would argue (and hope) that demographics and personal characteristics hold much less sway than they did five decades ago, particularly in a society where most women work outside the home and most people have equal civil rights under the law. Perhaps our assumptions about modern society are overly optimistic, but it’s been our experience that dimensions of similarity today are far more impactful if they are chosen, rather than innate, characteristics. Ultimately, it’s a shared passion or shared pursuit that brings the greatest bond.

The question then becomes how to uncover the pursuits and passions of your customers and prospects. We explored this question earlier in the book but offer another tool here: modest self-disclosure. Relationships are ultimately about reciprocity: responding to a question with an answer, asking a follow-up question to show your interest in understanding the person better, returning a phone call, returning a favor, and so on. If at any time the dance of reciprocity stops, the relationship falters. A modest self-disclosure is a gambit in the game of reciprocity, a subtle expression of your interests that begs for a similar disclosure in return. You might disclose your hobby, your weekend plans, your favorite movie, a cute story about your kids, your most recent purchase in the category—whatever might catch the prospect’s attention and potentially deepen the conversation about what you’re selling. As one top performer told us:

“I have a view of the selling process as involving a great deal of reciprocity. The object is for them to buy something from me, and for me not to buy something from them. And the question is always: How do you balance their rather overloaded contribution to my rather underloaded contribution? Some salespeople do this with lunches. Some do it with all kinds of little acts of entertainment. In the world of reciprocity, the fulcrum balances on reciprocal disclosures of intimacy. So the client is going to have some disclosures about money that I won’t have to make. I am really willing to tell stories that make myself look fumbling, or share some personal information that might be tangentially related to the sale, to try to put people at ease. . . . It’s not that I’ll say anything, but I’ll say what needs to be said to communicate to the client that I’m approachable and I have something in common with them.”

EXERCISES

• Observe your customers closely to better discern what their interests might be. Notice what they wear, what’s in their offices, what they drive, what appointments they have before or after meeting with you, the stories they tell about their family, and so on.

• Make a modest self-disclosure and observe whether it is reciprocated and ultimately deepens the relationship.

EXPRESSION 4:

GIVE THE DOCENT’S TOUR

“[From] the Latin word docere, meaning ‘to teach’. . .

Docents are educators, trained to further the public’s

understanding of [an institution’s] cultural and historical

collections. . . . They are normally volunteers . . . [who]

undergo an intensive training process . . . which teaches

them good communicative and interpretive skills, as well

as introduces them to the institution’s collection and its

historical significance. They are also provided with reading

lists. . . . Docents are kept up-to-date with continuous

training and seminars. Docents can be found at many

institutions, including local and national museums, zoos,

historical landmarks, and parks.”

—WEBSTER’S ONLINE DICTIONARY

When it comes to selling luxury, those who do it best are equal parts salesperson and museum docent. Consider the parallels. The fine art in a museum, for example, needs explanation and education for most people to fully understand and appreciate it. To untrained eyes, a Rembrandt looks a lot like a Renoir and a Picasso a lot like a Pollock. Into the educational void steps the docent, who must:

• Know history in order to place the artist in historical context; to understand the social movements and other artists he or she was influenced by (or rebelling against); to fit the work into its social context.

• Understand the provenance and history of specific works of art, supplying stories of past owners and past exhibitions that engage attention and perhaps provide some mystery (e.g., “The Mona Lisa was owned by both Louis XIV and Napoleon before being moved to the Louvre, where it was stolen in 1911. . . “).

• Be able to communicate the subtle differences that distinguish one artist from another, or an artist’s early efforts from his or her late works.

• Know the materials and processes in detail—drawings or paintings, oil or watercolor, canvas or paper, representational or abstract.

• Answer questions “off the top of his or her head” and without condescension. In a docent’s museum or a salesperson’s showroom, a response of “I’ll find the answer and get back to you” doesn’t meet customer expectations.

In short, docents are masters at educating people on subtle points of differentiation, and, in particular, the details that separate the merely good from true masterworks. And in one of the ultimate displays of passion for a topic, they do it for free. Few patrons hesitate to interact with them (“Hey, they’re passionate about the topic—of course they’d like to talk with me and answer my questions”), and few question the objectivity of their information (“It’s not like they’re trying to sell anything . . .”). In terms of storytelling approach and knowledge of details, most salespeople would be wise to follow the path of the docent. And although you’re not expected to do your job for free, you do need to become thought of as an objective source of advice—a resource for education—and not be viewed as “selling every minute.” There’s another parallel between a museum docent and an effective salesperson: role of guide. A docent guides visitors through the museum, taking in the different galleries, explaining the museum’s history and layout, occasionally introducing experts on this artist or that piece of work. A docent provides a mental map for patrons, one that covers the entire museum, and not just the docent’s specific area of interest. A good salesperson will do the same, when possible. One top sales associate at an elite department store described her job as “not just helping customers buy from the floor I happen to find them on . . . it’s a total walk.”

That phrase “total walk” came up in our interviews several times. It means guiding customers throughout different departments, to different floors, exploring different merchandise. It may start with the suit, but soon extends to building an ensemble—the handbag, the accessories, the shoes, and so on. It obviously increases the revenue from that customer, but it also is more likely to turn a onetime customer into a devoted fan. The interdepartmental tour also builds a mental map for the customers, building their confidence to return to the store and navigate its many departments on their own.

We saw the docent’s tour, with an interesting interpersonal twist, at one of the most successful automobile dealerships in the country. They call it a “quick tour,” and it does indeed involve giving a tour of the dealership, but in a subtle and unstated way. Here’s an example: Before taking a prospect for a test-drive, the salesperson makes a photocopy of the prospect’s driver’s license. But instead of heading into the back room to make a photocopy himself (or herself), the salesperson says: “Hey, I need to make a copy of your driver’s license—want to walk with me?” And on the way there, they meet Joe, the finance guy. Joe smiles and waves; he and the prospect shake hands and exchange a few brief pleasantries. The salesperson and prospect move on, make the photocopy, and head out for the test-drive.

Toward the end of the test-drive, the salesperson asks: “Can I show you something you won’t see anyplace else?” It’s hard to say no to that one, and the salesperson instructs the prospect to turn into the dealership’s service center. And it is, indeed, like a service center the prospect won’t see anywhere else. It is spotless. Not just the waiting room, but also the service bays. For a place where cars are repaired, there is a truly remarkable lack of dirt, grease, or oil. Next to it is a warehouse of inventoried parts, equally spotless, that ensures that customers won’t be inconvenienced or be forced to drive loaner vehicles while “waiting for parts to come in.” The place hums with activity but isn’t frenetic. The staff is busy, but calm and friendly. One gets the sense of well-oiled machines, both literally in the machinery in the place and figuratively in the systems that coordinate the people. In short, everything the prospect sees here exudes pride, preparation, and professionalism. The prospect doesn’t hear about these qualities in a sales pitch but sees it for himself.

The prospect sees more unusual sights. Outside the service center cars are lined up for free car washes, which this dealership offers for life. Those washing the cars greet their customers with a smile and know their customers by name. Susan, the head of the service department, then greets the customers, again offering a handshake and quick exchange of pleasantries. Then it’s back to the dealership to debrief the customer about the test-drive and listen intently to what he might want next.

Consider the power of this simple technique. The prospect has seen the entire dealership; with a mental map of the setup, the process arouses no barriers or objections. Unlike asking, “Can I show you around the dealership?” or some other question guaranteed to raise flags and slow the process, the salesperson has asked only for a walk-along to the copy machine and the innocuous question, “Can I show you something you won’t see anyplace else?” Furthermore, the quick tour has subtly shown off the dealership’s strengths and differentiators—with a world-class service department, it’s no surprise that was a prime stop on the tour. It also has the simultaneous benefit of putting the prospect at ease socially. When it comes time to finance the vehicle, there’s no fear of an ominous “finance department,” staffed by unknown people who might make the process difficult. No, they are going back to work with Joe, whom they have already met, and who seemed like a perfectly fine fellow. This dealership prides itself on taking care of its customers, and also in being a pleasant place to work as well as to buy a vehicle. It’s one thing for a salesperson to say it; in fact, probably every salesperson does say it. But the quick tour illustrates the proof points—everyone the customer meets seems professional and quite happy to be working there.

EXERCISES

• Visit your local museum. First, walk around for an hour, gleaning whatever insights you can, based on your own observations. Then take a docent’s tour. Observe the docent’s style and see how much more you learned on a guided tour.

• Revisit how you sell. How would a museum docent present—in an objective, engaging, story-based way—what you sell? What are the detail-rich stories of history and quality that are “must tell”?

• Design a docent’s tour that subtly shows off the very best of the brand you offer.

EXPRESSION 5:

UNDERSTAND THEIR ULTIMATE PASSION:

FAMILY

“A family is a place where minds come

in contact with one another.”

—BUDDHA

We saw in Chapter 3 that family interests consistently top the lists of passions for the affluent. Depending on your product category and your sales style, understanding customers’ family situations may be a powerful way of deepening your relationship with those customers and prospects. But as it is the ultimate passion for these people, tread carefully on the subject of family. It is easy to invade a customer’s comfort zone when it comes to sharing information about family.

Understanding the family situation is obviously of particular importance for those in sales in the financial services industry. Has a new baby changed the customer’s need for life insurance? Are there more kids on the way? Has there been a financial switch from a dual-income household to a single-income breadwinner-homemaker household? Is there a child heading to college soon, necessitating that some cash be freed up for tuition payments? Is there a “boomerang kid”—one who has returned home after college, and may need some guidance in getting a job and becoming financially independent? Is an aging parent putting a near-term financial burden on your customer, a burden that may soon paradoxically morph into a significant inheritance?

It is one thing to know the ages of your prospects and their family members, and to understand the likely changes in lifestyle and income. But there’s another level of understanding: knowing the needs and attitudes of family members, their personalities and preferences, their ambitions and fears. For the wealthy, for example, there is significant concern that money might undermine the tight family life they have tried to create. Among 700,000 or so households with $500,000 or more in annual discretionary income, a group that averages over $12 million in assets, fully half express serious concerns about their children’s work ethic because they have grown up with money. Abundance creates new fears and new expectations. More than two-thirds of these adults want their heirs to be “stewards of the family wealth,” managing it and passing it on to future generations. In contrast, only 49 percent agree with the statement: “I do not care what my heirs do with the family wealth; I just want them to be happy.”

The wealthy reach out to their kids with guidance and information, particularly since the Great Recession has elevated everyone’s financial stress. Three-fourths of them have taken specific steps to educate their kids about financial decision making (but most stop short of revealing the full value of their estate). Other families have chosen to “outsource” the solution; instead of dealing with it “in-house,” they defer to a new cottage industry offering financial how-to seminars for children of the newly wealthy. Either way, financial service providers are obviously well advised to be part of the family education process; they just have to understand the familial “lay of the land” to position themselves effectively.

One might expect that social media sites are great places to keep up with customers and their family members, and although there is potential there, tread carefully: In general, social networking sites such as Facebook aren’t great places for selling. At least for the moment, the closest technological analogy to Facebook is the telephone. Consumers love it as a medium to communicate with friends and family but find it terribly intrusive when used for marketing. Less than one in three affluent Facebook users is a friend or fan of a company or product, and less than 5 percent have made a purchase decision largely based on information and ideas found on Facebook.

Of course, the relative noncommercial focus of social media sites may change as they evolve, and they certainly evolve rapidly. But today, a number of top sales performers tell us they use social media sites less as tools for broadcasting their offerings and more for listening to their customers. They maintain a minimal presence, careful to avoid being too “salesy” or posting something they wouldn’t want a prospect to know about them. Their posts tend to focus on their personal and professional passions. (For example, one salesman focuses his posts on his training for an upcoming marathon, implicitly illustrating his energy as well as his ability to set and achieve big goals.)

Instead, top-performing salespeople tend to use social media sites more for “listening” than for promoting themselves or explicitly selling. And they find that information about their customers shows up on social networking sites long before it would typically filter to their financial adviser, real estate agent, travel agent, personal shopper, personal trainer, or any number of other service providers and sales-people. Facebook isn’t just about keeping up with friends and family (or playing Farmville). It’s often the first venue for the dissemination of information about new jobs, new kids, new business ventures, job promotions, which kids are attending new schools, family travel plans, and so on. In short, these sites are a valuable line of communication, although that communication is surprisingly more one-sided than social media are typically thought to be.

Of course, understanding the family dynamics of a customer doesn’t just help the provider of financial services. Top salespeople in many categories keep detailed customer files and use them to mark occasions (such as by sending handwritten birthday cards) important to the customer and his or her family. Ultimately, the details of gathering and using information are less important than is expressing a sincere interest in those closest to your customers.

• Conduct a “family census,” putting into writing everything you know about your customers’ families.

• Form an action plan for learning more about your customers and their families.

• Customize your approaches and offerings to these customers. How can you meet the needs of family as well as the individual?

EXPRESSION 6:

SATISFY THE PASSION DU JOUR: VALUE

“Price is what you pay. Value is what you get.”

—WARREN BUFFETT

Family has been, and will continue to be, the ultimate passion for most people. But the newest and most pressing passion—one that extends through every financial strata—is value.

Among the affluent and wealthy, we first saw the seeds of this tremendous focus on value germinate in 2006. The National Bureau of Economic Research, the private group of economists charged with dating recessions, put the start of our recent Great Recession at December 2007. In fact, we saw an “emotional recession,” with declining optimism, spending cutbacks, and a growing focus on value, take root as much as eighteen months earlier. The turmoil and uncertainty of the ensuing years only served to heighten this value orientation, and it required considerable experience to navigate the marketplace with a fundamentally different set of trade-offs.

According to our survey, among the affluent:

• 86 percent prefer to shop in stores with reputations for great pricing.

• 74 percent usually wait for something to go on sale before buying it.

• 64 percent shop regularly with coupons (that’s right, coupons).

It is important to recognize that the dynamic at work here is value orientation, not necessarily price sensitivity. In fact, across a variety of product categories, the affluent have shown tremendous reluctance to buy the lowest-cost option or to trade down in quality. When we asked how the economy was reshaping their personal travel plans, for example, one of the most common responses was: “Staying in the same quality of accommodations, but expecting a better deal.” Similarly, they told us they were making fewer high-end purchases, but ones that were more personally meaningful—again speaking to the unwillingness to trade down. Nowhere is this dynamic better reflected than at Costco, which is extremely popular among the wealthy, with its unique treasure-hunt approach to a surprising range of products across price ranges. (Costco is among the world’s largest retailers of high-end wines and high-quality diamonds, for example.) Wal-Mart, however, with its low-cost/low-quality approach, garners much less enthusiasm (and share of wallet) among the financial elite.

We saw similar dynamics when we asked affluent individuals what words they would use to describe themselves, and what words make them more or less interested in various marketplace offerings. The list of top ten words that describe themselves (see Table 5.1) can be summarized as wise and nearly puritanical, while the bottom ten words largely reflect the superfluous and insubstantial kind of characterization they disdain. The picture becomes even more telling when one examines the words that engage their interest in products and services: value, values, savings, deals, and best. They reflect a value orientation, to be sure, but just as important is being consistent with their values and maintaining high quality. The words that turn them off reflect those things that seem gimmicky and don’t stand the test of time.

The importance of value to this group is apparent, not just in their retail choices but across virtually every other category of goods and services. Consider travel. Just a few years ago, very high-priced destination clubs and other vacation concepts were successful products among the wealthy, largely through a “lifestyle sell”: high-end accommodations, multiple destinations, fabulous vacation experiences. Some commanded initiation fees in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, with annual maintenance fees in the tens of thousands. These clubs typically offered little in the way of equity or investment potential, but customer interest was nevertheless reasonably strong. The recession put a sudden and dramatic end to that entire business model, however. By mid-2010, interest in vacations was rising, especially a growing interest in high-quality vacation homes, fractional properties, and time-shares. Whereas in 2006, these consumers wanted a fabulous vacation experience, by 2010 they were insisting on an investment-grade fabulous vacation experience. And their standards for what constituted “fabulous” were no less demanding. Investment-grade quality (figuratively speaking) and value continue to be the new “must-haves,” regardless of whether the offering is mainstream or luxury.

TABLE 5.1

Words That Resonate (or Not) with the Affluent

• Strengthen your value equation. In workshops where we ask salespeople to list how many ways they and their brands add value, the best come up with dozens of ways.

• Revisit how you communicate your value proposition.

• Increase value instead of lowering prices.

Remember: Lowering prices is a strategy fraught with peril in luxury categories. It diminishes perceived quality, dilutes one’s brand image, and makes past customers feel their full-price purchases were bad decisions. Plus, you’ll find it much harder to raise prices again later—today’s discounted price is tomorrow’s expected price.

EXPRESSION 7:

USE THE LANGUAGE OF PASSION

“The language of truth is simple.”

—EURIPIDES

“Think like a wise man but communicate

in the language of the people.”

—WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS

In our interviews with the affluent and wealthy, we were struck by the characteristic ways they express themselves. We analyzed these interviews and discovered that certain words and phrases were used with great regularity, and we noticed that other words and phrases were conspicuous by their absence (see Table 5.2). The words these groups use might be characterized as “the language of passion”: mission, guts, future, vision, entrepreneur, right, wrong, happy. Generally, they express their thoughts with a clear preference for short, simple words; active verbs; straightforward nouns; and results-oriented terminology.

TABLE 5.2

Words of Character and Complexity

In contrast, our research showed that they tend to be turned off by flowery language, anything that conveys faux sophistication, and an abundance of adjectives and adverbs. In other words, they dislike the kind of language that untrained salespeople routinely use to try to impress the wealthy. Their feeble communication strategies—both written and verbal—backfire, triggering the fine-tuned BS detectors of today’s wealthy. Advertising copy for luxury products is often an example of this offense—filled with multisyllabic descriptors that obscure the message.

Conduct a language audit of how you communicate with prospects. Evaluate the words you use in your elevator pitch, in your sales scripts, on your Web site, in your sales collateral, and in every other aspect of your sales and marketing mix. Are you using the simplest and most powerful detail-rich language that will engage your customers and prospects?

EXPRESSION 8:

UNDERSTAND THAT RELIABILITY

IS “THE NEW TRUST”

“Confidence, like the soul, never returns

whence it has once departed.”

—PUBLILIUS SYRUS

For reasons we have already explored, trust has become difficult, if not impossible, to achieve in a typical sales context. But trust is an important and multifaceted concept, and it bears deeper examination. Giving up on it completely would be premature.

Academic researchers, for example, have empirically distinguished between affective and cognitive forms of trust. In sales, affective trust refers to an emotional connection, a comfort level, a feeling that the provider has the customer’s best interests at heart. Cognitive trust is a bit “colder” and refers to the rational knowledge of the provider’s track record, the belief that he or she is a qualified and knowledgeable individual, the fact base that he or she has about the company he or she represents, and so on. Today, affective trust has become particularly rare and challenging for the salesperson to gain or maintain. Cognitive, rational trust may still be within reach, even though it is qualitatively different from how most people conceptualize trust.

The best approach to building cognitive trust with your prospects is to simply do what you say you will do. In a very real sense, reliability is the new trust. More than ever, you will be judged by your ability to execute, to follow through, to simply keep your word. If you say you will follow up with a phone call tomorrow, do it. If you say you will send a packet of information next week, do it. If you say you will publish your newsletter every two weeks, do it. If you say you will show up at noon tomorrow, you’d better do it, as one exceptional salesperson found out the hard way:

“Not being on time is deadly. I had a meeting at which I was selling a very complicated set of studies, with many millions of dollars on the table, to a large client in the entertainment business. I was in Century City that morning interviewing a job candidate, and I got too engaged and lost track of time. We left Century City too late to make it to the meeting unless there was perfect traffic, and of course there wasn’t. I called his VP to tell him we would be a few minutes late. But we ended up being more than a few minutes late. When we arrived, his secretary came to the lobby and told me: ‘He’d wait fifteen minutes for Jack Nicholson but not for an [expletive] like you.’ End of deal.”

There’s a deeply unfair but nevertheless real asymmetry to reliability: Keeping your word may not get you a lot of credit, but failure to do so will irreparably undermine your credibility. (Interestingly, it’s much the same dynamic for environmentally friendly offerings: Being green won’t get you the sale, but not being green may prevent you from getting the sale.)

EXPRESSION 9:

CREATE A RITUAL OF CELEBRATION

Closing a sale is cause for celebration. The salesperson’s reasons for wanting to celebrate are obvious. But commemorations of a transaction are perhaps even more important for the customer. Rituals of celebration put an emotional exclamation point on an otherwise rational and behavioral event. They reduce postpurchase regret and buyer’s remorse. They offer another point of connection between salesperson and customer, deepening the relationship and increasing the likelihood of the individual’s becoming a repeat purchaser and a long-term customer.

Don’t be put off by the term ritual. The event can be extraordinarily simple. Consider Hermès. Sales associates don’t slap your purchase in a bag and hand it across the counter casually. It is carefully wrapped in a signature orange bag. The sales associate typically comes out from behind the counter. He or she presents it to you respectfully, with both hands, and expresses happiness for your purchase. As rituals go, it’s fast, simple, and powerful. Years ago, Saturn leveraged the emotional power of a ritual of celebration as well. In a classic ad, it showed sales associates gathered around to celebrate a customer’s purchase of her first car. They gave her the keys, everyone applauded, and the emotional impact was immense.

EXERCISE

Create a ritual of celebration to mark the “consummation” of transactions with your customers.

EXPRESSION 10:

COMMUNICATE A COMPELLING

BRAND PROMISE

“What’s a brand? A singular idea that you own

inside the mind of the prospect.”

—AL RIES

“I am not looking like Armani today and somebody

else tomorrow. I look like Ralph Lauren. And my goal

is to consistently move in fashion and move in style

without giving up what I am.”

—RALPH LAUREN

Brands are one of the most powerful tools in the arsenal of the salesperson. In our book The New Elite, we posed the following thought experiment: Suppose you could own all aspects of Mercedes-Benz—the manufacturing plants, the distribution pipeline, the dealerships, and the customers. Or you could own the name Mercedes-Benz. Which would you choose? Of course, you would choose the name. All the physical assets of the company could reliably be replicated in relatively short order with enough money. The name, however, and all the rich emotional connections with it, could be reconstructed only with decades of effort, dedication, and consistent performance.

Branding is important in two realms. Most obviously, there is the brand of what you are selling or the company you represent. And then there is your own brand, as a person and a professional. Communicating both brands in a compelling way is a key strategy for enhancing your sales. Ideally, the meaning of a brand—what we call the brand promise—can be conveyed in a single word or phrase. For example, in the minds of most people, “Volvo” and “safety” are synonymous. Similarly, “BMW” is “finely engineered” and “Apple” is “innovative design.” Can you capture the essence of your brand in a single word or phrase?

Great brand promises, be they for corporate brands or for individual salespeople, are built upon three key elements.

1. Truth. The brand promise must be inarguably, factually correct. It must stem from one’s strengths and passions. Volvo, for example, can make safety the core of its brand promise because the company’s products are, in fact, demonstrably safe, with a heritage of safety innovations built into their corporate DNA. To prospects, untrue brand promises will be patently obvious and come across as inauthentic.

2. Meaning. A brand promise must be meaningful to clients and prospects. It must speak to their needs and be consistent with their values and passions. Safety in a car doesn’t speak to everyone, but it is meaningful to the folks that Volvo targets.

3. Distinctiveness. The ideal brand promise is unique to that brand and stands out from the competitors’ promises.

EXERCISES

• Make a list of what is true, meaningful, and distinctive about (a) the brands you sell/represent, and (b) you as a sales professional.

• Distill the meaning of your brand down to a single word or phrase.

• Practice communicating your brand essence to prospects and customers.

EXPRESSION 11:

HONE A COMPELLING ELEVATOR PITCH

“Communication works for those who work at it.”

—JOHN POWELL

We hope you are passionate about your job. Or you’re working to get there. Or you’ve set out to find out what your passion is and what the environment is that would be a good fit. That’s great. But it’s not enough.

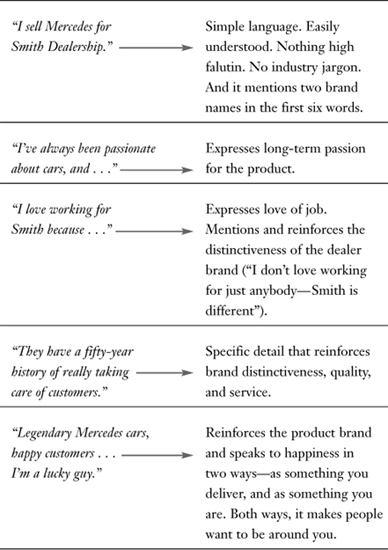

You’ve got to be able to communicate that passion in ways that are authentic and engaging. Expressing the love for your job is a good start. But a compelling elevator pitch is just as important. We’ve all heard the concept: Imagine you’re in an elevator with someone, and you’ve got thirty seconds to explain who you are and what your business proposition is. That is, your elevator pitch should be pithy and punchy, packed with benefits. You can find books and Web sites devoted to creating and refining one. But here’s how you can create the most influential elevator pitch: Make sure it touches all three passions discussed in this book (a sincere love for what you do, alignment with your prospect’s pursuit of a sincere interest, and the transcendent nature of your offering). Here’s a very simple but very effective example:

“I sell Mercedes for Smith Dealership. I’ve always been passionate about cars, and I love working for Smith because they have a fifty-year history of really taking care of customers. Legendary Mercedes cars, happy customers . . . I’m a lucky guy.”

Now let’s take a look at Figure 5.1 to see what makes this pitch effective.

FIGURE 5.1

An Effective Elevator Pitch

The example elevator pitch in Figure 5.1 is short, but it grabs attention, conveys a tremendous amount, and speaks to all three passions. Now, it’s time to polish yours.

EXERCISES

• Draft your elevator pitch with passion, brands, and happiness at the core.

• Refine your elevator pitch based on feedback from friends and colleagues.

• Practice your elevator pitch until it feels natural and authentic.

EXPRESSION 12:

ASK PASSION-BASED QUESTIONS

“If you want a wise answer, ask a reasonable question.”

—JOHANN WOLFGANG VON GOETHE

“A sudden bold and unexpected question doth

many times surprise a man and lay him open.”

—FRANCIS BACON

Books on sales methods are fond of teaching the art of asking questions. And for good reason. Asking questions and listening to the answers are crucial steps to the sales process. Sometimes attempts to manipulate the question-asking process can be taken to extreme lengths. We saw in an earlier chapter just how many decades those classic sales questioning techniques have been around, like asking questions that lead to patterns of affirmative responses or asking leading questions like “What color do you want it in?” rather than “Do you want it?”

We’d like to add a subtlety to the extensive literature on asking sales questions: the passion-based question. This simply means asking questions like a true enthusiast. It’s about letting down your guard. It is less about crafting carefully worded questions designed to elicit a specific response, and more about sharing your passion in a way that is spontaneous and sincere. And these questions have the added benefit of nearly always generating a positive response in a natural and authentic way. Who can resist questions such as:

• Do you want to see something very cool?

• Do you want to see something you can’t see anywhere else?

• You know what I’m into these days?

• You want to know what really makes this brand different from other ones?

• Do you want to see something truly exceptional about this product?

• You know what first excited me about this business?

• You know what my first car was? (appropriate for auto salesmen with interesting stories to tell about their love of their first car)

EXERCISE

Craft some passion-based questions that you can use to deepen your interactions with customers and prospects.

EXPRESSION 13:

SELL TO HAPPINESS

Even during the most challenging economic times since the Great Depression, happiness has been on the rise among the affluent, and nearly seven in ten now describe themselves as very happy (see Figure 5.2). It is not a happiness of self-delusion or escapism. It is a solid happiness, with strong psychological foundations. For example, 76 percent of those we surveyed felt highly successful in their personal lives (our general population surveys suggest that only half of the public at large feel highly successful). It is, in a sense, a rational exuberance. This is not a denial of today’s economic problems but, rather, the confidence that results from challenges well met. For example, 72 percent of the affluent sampled agree with the statement: “I have become a much smarter shopper thanks to today’s economic situation.”

FIGURE 5.2

Percentages of the Affluent Who Describe

Themselves as Very Happy, 2007–2010

Here’s the key: Today’s affluent consumers do not buy to become happy; they buy because they are happy.

One way to sell to happiness is simply to be happy yourself. This simple act pulls together several of the techniques we have discussed in this chapter. Happiness is an extension of expressing the love you have for your job, and your sincere love of your life. And happiness is perhaps the most important characteristic you can share with your prospects. Revel in their happiness, too. Try to take it even further. As one of our wealthy research participants put it:

“I’m very passionate about putting forth the best for other people. Other people’s happiness is as important to me as my own. And when they come to my business, my winery, and they tell me they had just the greatest time—that is the biggest motivator to me. To continue to put forth the effort to make people come out and go ‘wow’—that’s motivating to me. I’m very passionate about that. If I sell crap wine . . . I could be successful and make a lot of money if that’s success to you. But when you make a product from start to finish and grow it and make it and mold it and massage it and kiss it, just do everything you do from start to finish, you’re giving it your all.”

EXERCISES

• Be happy.

• Express your happiness.

• Understand what would make your customers even happier.

THE NEXT STEP

You’ve read our top thirteen ways of expressing passion in a selling context. We’re sure there are many more possibilities (send us an e-mail—we’d love to hear yours). But for now, read on to the next chapter—about how to set goals and structure your work to maximize your ability to follow through and succeed.