CHAPTER TWO

The Passion of the Salesperson

“Nothing great in the world has ever been

accomplished without passion.”

—GEORG WILHELM FRIEDRICH HEGEL

“Desire is the starting point of all achievement,

not a hope, not a wish, but a keen pulsating desire,

which transcends everything.”

—NAPOLEON HILL

“There is no passion to be found playing small—in settling

for a life that is less than the one you are capable of living.”

—NELSON MANDELA

WE’VE INTERVIEWED AND TRAINED hundreds of successful salespeople who make their livelihood by building relationships with wealthy individuals. The first and most obvious impression one gets of these top performers is that they have, for a lack of a better phrase, a sense of passion.

Let’s not let semantics get in the way. If, for you, what we are talking about is not passion, then choose your own word: Drive. Hunger. Persistence. Determination. Tenacity. Relentlessness. Focus. Intensity. Proactivity. Or, choose your cliché to describe these individuals: “They take the bull by the horns.” “They get it done.” “They make their own luck.” “They have a fire in the belly.” “They are positive thinkers.” “They don’t take no for an answer.”

A PASSION FOR SALES

In some top salespeople, the passion for sales manifests itself as a quiet confidence or a steely determination. This archetype is found throughout the research, history, and mythology of sales success. For example, thirty-five years before Ross Perot’s focused, unblinking gaze caught the nation’s attention during his presidential run, he used that determination to become one of the greatest salesmen in IBM’s history. In his final year with the company, he achieved his annual sales goal by January 19. Or so the story goes. And it’s a good story, often retold, with Perot achieving unofficial hall-of-fame status in the competitive world of sales.

How Perot might have managed such a feat is probably unknowable at this point. Time investigated the claim during Perot’s 1992 presidential campaign, interviewing more than twenty of Perot’s colleagues from his IBM days, but the magazine was forced to concede: “Some of their memories are fading, a number of key players are dead, and documents are virtually nonexistent.”1 It’s clear, though, that he wasn’t widely liked, with descriptions of Perot ranging from “immoral,” to a more politically correct “not a team player,” to a more charitable “He was practicing ‘80s ethics in the 1960s.” He likely wouldn’t disagree; he once described his “role in life is that of the grain of sand to the oyster—it irritates the oyster and out comes a pearl.”2

Regardless of the story’s validity, it’s clear that Ross Perot was widely respected for his sales ability—and his drive, in particular. One colleague summed it up this way: “I still don’t like him . . . but I’ve never seen anybody who could accomplish as much as this son of a gun could.” In 1962, Perot left his five-year stint at IBM to start Electronic Data Systems (EDS), and (possibly apocryphal sales story no. 2) had his sales pitches rejected seventy-nine times before he landed his first client. But, mythology aside, it’s clear that Perot’s drive was truly exceptional and he got inarguable results. EDS went public within just six years of its founding, with its stock price rising from $16 to $160 within days of its Initial Public Offering, launching Perot from the ranks of millionaires to the ranks of billionaires. He never tempered his style. Soon after selling EDS to General Motors for over $2.4 billion (in 1984), he became a vocal critic of GM’s quality, concluding that “revitalizing GM is like teaching an elephant to tap dance. You find the sensitive parts and start poking.”3

Whether you like Ross Perot or not doesn’t matter. We are not putting him on a pedestal or holding him up as an ideal. Instead, he’s offered here as the archetype—the highly successful salesperson, driven by his passion for sales. He’s relentless, determined, and—to use our word—passionate. Sometimes to a fault.

This same image of a relentless, driven person is found repeatedly in the world of sales, and among entrepreneurs more generally. Think of Donald Trump. Mark Cuban. Boardwalk barkers cum infomercial screamers such as the late Billy Mays. The persona is at the core of the sales-motivation subculture, in which Tony Robbins is merely the best known member. Dozens of sales gurus have dedicated followings of various sizes, and their followers collectively spend millions of dollars on books, audio programs, and seminars meant to help them enhance sales performance.

There is always an underlying truth to archetypes and mythology, even if the details don’t always hold up to scientific scrutiny. (Comedian Stephen Colbert’s concept of “truthiness” comes to mind: a form of truth known intuitively “from the gut, not books,” without regard to evidence or logical examination.) And there is certainly profound truth to the notion of passion being at the core of sales success. As the following two case studies show, this particular truth is widely supported by both research and experience.

CASE STUDY

Top Sales Performers on Fifth Avenue

We’ve heard about the power of passion virtually every time we’ve interviewed top performers. For example, we developed a training program for sales associates and personal shoppers at one of the world’s most prestigious luxury retail stores. It’s the kind of store that piqued Carrie Bradshaw’s enthusiasm on Sex and the City. While the elite clientele varies throughout the day, the store’s patrons are consistent in having large wallets and high standards. These ladies who lunch pop in en masse at midday, and a small fashion posse of them collectively might spend six figures. Likewise, CEOs visit after work for $10,000 suits. After hours, VIPs with special security concerns are brought in for shopping sprees that range into the millions: Saudi royalty one night, international celebrities the next.

We started our interviews with the best sales associates and personal shoppers—those whose commission-based compensation is well into the six figures. We asked them about the secret of their success in retail sales. First, we needed to coax them past any objections they may have had to the word success; their modesty is consistent with the modesty we often see in successful individuals across professions, sales or not. But there was method to our madness. Getting people to talk about their professional successes is a powerful way to start an interview; it is flattering, of course, but it also engages their curiosity. We have often said that our biggest research challenge is finding successful salespeople and wealthy individuals willing to be interviewed. Our second biggest is getting them to stop talking once we’ve started the interview.

Our interviews often start with questions about the reasons for their success, and they often lead to the same answer: the passion thing. We’ve often heard about the effort, and the attitude, and the hunger, and it features in these interviews.

• “Hunger. Drive. Desire.”

• “It’s not about opening a door. Anybody can do that. You really have to work it.”

• “Really putting in the hours and the effort. Being productive during downtime.”

• “I see a lot of standing around, and I just say to myself: ‘My God, there is so much to be done!’”

• “I go the extra mile. I put a lot of effort in. I follow up. I stay in touch.”

• “I ended up building my business in my quiet times. I realized that I had to reach out, instead of just standing there waiting for business to walk in.”

• “I’m always busy. I’m calling. I’m sending notes. I will call and say I’m putting together a little package. I will e-mail clients I haven’t heard from in a month or two. I’ll send them a little something for their birthday, or grandkids being born, or bar mitzvahs. If somebody has a benefit, I’ll have the store give a gift certificate. The list goes on.”

We spoke to the store’s vice president responsible for all the sales associates and personal shoppers, including the hiring and firing. As in many sales organizations, the company brings in many entry-level individuals, a handful of whom rise to elite heights and some of whom under-achieve and leave quickly. The cost to the store is considerable (time and money wasted on hiring and training), and the cost to the unsuccessful associate is considerable as well (wasted time and an unnecessary emotional toll). But through experience and research, the recruiting process at this store has become a refined and targeted effort to recruit, hire, and foster the growth of those most likely to succeed. As our vice president put it, she looks for:

“Someone who really has a passion for what they do. It has to be more than: ‘I love to be around people. . . . I love to be around clothing.’ When I interview somebody who says that to me, I have red flags that go up. Yeah, we all love to be around people and clothing—that’s why we do what we do. But there’s got to be something else . . . there’s got to be an edge. Being personable. Being organized. Understanding that you are a businessperson and knowing how you are running your business. Thinking outside the box to take yourself to the next level. Getting all the knowledge you need—not just standing by a register and thinking the traffic is going to come to you. Knowing what’s going on in the world, and relating that back to what you do. Somebody who is a go-getter. Somebody who says: ‘This is it. This is what I want.’ Not somebody who sees it as a 9-to-5 job, but somebody who sees it as a career path. Someone who understands what clientele-ing is all about, and what our store is all about in terms of customer standards, and so on.”

CASE STUDY

Top Sales Performers in a

Dallas Luxury Auto Dealership

Different company, different industry, different location—but remarkably similar insights into what determines success. As with the previous case study, we interviewed top performers, this time at one of the most successful luxury automobile dealerships in America, to hear their secrets of success. Here’s what they had to say:

• “First, make sure this is what you want to do. Think about what kind of person you want to be. It’s less about making money, and more about your own personal development. If you are just dabbling, don’t do it.”

• “Sometimes new people say, ‘Oh, look at her . . . she just works 9 to 6. Must be nice.’ I don’t work 9 to 6. They don’t see me at home working at 10 or 11 at night. I’m up at 5 every morning on the computer. You’re not going to make $100,000 your first year working 9 to 5. I didn’t build my business in a year.”

• “Networking was huge for me when I started. It’s so important not to sit here and wait for people to come through the door. It’s just not going to happen. You have to get out there and build relationships. Find something you enjoy with those people—then just get out there and connect.”

• “You’ve got to give it your best. You’ve got to think positive. You’ve got to go after it. Every morning, you have to have the mindset: ‘I can sell something today.’ If you’re not going to do that, you might as well take the day off.”

A PASSION FOR RELATIONSHIPS

Aside from having a passion for selling, another characteristic of highly successful salespeople is their passion for relationships. That doesn’t necessarily mean that they are extraverts or the life of the party. But they have and show an interest in the lives of others. It’s an intellectual interest, to be sure, with many salespeople being “armchair psychologists” who have read about or observed human behavior, particularly as it relates to sales and persuasion. But it is also a sincere and practical interest; they care about people.

Building relationships is the essence of successful sales. The goal is to turn that person who is a onetime sale into a repeat customer. And having a passion for developing relationships is key to making that change. Top sales performers confirm this:

• “The secret in luxury sales is to develop a following. You meet someone, and you give them such great service that the experience sticks with them, and the customer sticks with you.”

• “Top performers aren’t just concerned about the initial sale. They ask: ‘How do I form a relationship? How do I get their repeat business?’”

• “When I see a new piece come in, I ask myself: ‘Who could that be for?’ I don’t wait for the customer to come to me.”

One of the very best, a retail salesperson generating an income well into the six-figure range, summed it up well:

“[Top performers] aren’t just focused on taking it and ringing it. They are truly interacting with clients. Mediocre performers are just clerking sales or ringing sales, instead of finding out: ‘How can I get this client to come back?’ Top performers aren’t just concerned about this initial sale. They ask: ‘How do I form a relationship? How do I get their repeat business?’ Because that’s really where the business is and where the money gets made. It’s not about taking this one sale—that one sale could come back. ‘How do I connect with this client to make her want to work with me again? How can I make her OK with me calling her again, sending her photos of new merchandise, etc.? How do I start that relationship?’ The associate that takes that extra step—that isn’t just happy with this one sale—that associate is the one who wins in the end, because that is the associate that clients want to work with.”

THE LONG HISTORY OF

PASSION-BASED SELLING

That passion stands at the core of sales success is both a very old and a very new notion. Before there were brick-and-mortar bookstores and community libraries, and long before there was the Internet, publishers hired peddlers to sell their books. Bible societies in particular had large sales forces, many of whom were known for their fervor; they were, after all, selling not merely books but also salvation—in their minds, they were literally selling the very word of God. Ebeneezer Hannaford’s Success in Canvassing: A Practical Manual of Hints and Instructions, Specifically Adapted to the Use of Book Canvassers of the Better Class, published in 1875, preached the importance of persistence, hard work, and passion as essential to selling (even presenting topics in military terms, with chapter titles such as “Organizing for Victory” and “Opening the Campaign”).4 Similarly, snake oil salesmen were known for their impassioned sales pitches. The main character in Abraham Cahan’s 1917 book The Rise of David Levinsky says: “I developed into a successful salesman. If I were asked to name some single element of my success on the road, I should mention the enthusiasm with which I usually spoke of my merchandise. It was genuine, and it was contagious. Retailers could not help believing that I believed in my goods.”5

The idea of passion is a thread that continues to run through sales today. Og Mandingo’s 1968 book The Greatest Salesman in the World, which continues to be widely read today, gives the simple message: “do it now.” In his 2005 book The Art of Selling to the Affluent, Matt Oechsli concludes that commandment number 1 is to “be totally committed.”6 When author Remy Stern interviewed Ron Popeil, the infomercial king whose autobiography is modestly titled The Salesman of the Century, he was struck by the obviousness of Popeil’s two great loves—cooking and selling. Popeil’s kitchen includes a floor-to-ceiling bookcase with “every sauce, condiment, and marinade imaginable,” as well as what he claims is one of the world’s largest collections of olive oil. And as for his passion for selling, Popeil has a professional video camera, a tripod, and a stack of videotapes, including tapes of him practicing infomercial pitches at all hours of the day and night.7

The Rise of Scientific Management

Although this idea of passion has been engrained in sales from its very beginning, it can be hard to quantify, predict, and systematize. As a result, passion took a backseat in thinking about sales success for several generations. The shift started with a movement known as scientific management, an attempt to bring rigor to the challenging task of managing growing organizations in the early era of mass production and marketing. Managers would carefully study individuals at work, break their efforts down into the smallest possible behaviors, and then install systems to teach those behaviors in great detail. Managerial control was crucial; individuality was an error in the system to be stamped out.

Frederick W. Taylor’s 1911 The Principles of Scientific Management was the bible of the movement, but the basic ideas had been percolating for decades, since the dawn of the industrial revolution. It wasn’t long before companies with large sales forces began applying these ideas to the previously wild, wooly, and radically idiosyncratic world of sales. In Scientific Sales Management: A Practical Application of the Principles of Scientific Management to Selling, Charles Wilson Hoyt wrote:

Scientific Sales Management believes in the proper training of the salesman. This training even goes down to the individual motions and work of the salesman. It goes so far as to insist upon the substitution of exact methods of work by the individual salesman for scattered efforts. This is carried out even to the matter of standardizing, in some propositions, the salesman’s talk, his manner of approach, etc.8

Perhaps the best known popularizer of these ideas was John Patterson of National Cash Register, whose huge sales force called on growing businesses around the country. He was certainly a believer in the role of passion in sales. The company newsletter, The Salesman, ran with the subtitle “Our Password: Hustle.” He sponsored motivational sales conferences. He paid high commissions to keep their energy up. He wrote:

A sickly, nervous man cannot exert that personal magnetism which unconsciously cuts such a large figure in the success of every salesman. Not only the practical manager of the sales department of every large corporation, but as well the professors who write on the psychology of salesmanship, insist that good health and abundant animal spirits are perhaps the most important qualifications a salesman can have for his work.9

“Abundant animal spirits” is certainly the most unique metaphor for passion we’ve come across in the sales literature, but it makes the point.

Despite his belief in passion, his even stronger belief in the “scientific” approach to sales meant putting systems and consistent terminology into place, much of which still exists in actuality or in spirit today. Daily reports on sales and prospecting submitted by 8:15 A.M. Monthly quotas overseen by sales managers, who met to review sales figures each Monday at 8 A.M. Sales scripts. Prepared answers for countering common objections. Persuasion techniques such as frequently asking questions guaranteed to get prospects to repeatedly say yes, or handing them a pen to push them toward signing a purchase order, or asking, “What color do you want?” rather than “Do you want it?” Expecting sales-people to “hustle collections as hard as they hustle for orders.” A four-step sales process: approach, proposition, demonstration, and close. A sales training school taught it all. There were clubs and awards for those making their quotas. There were sales-as-warfare analogies and calls to military discipline; Patterson said, “I believe that a business ought to be like a battleship in many respects—in cleanliness, in order, in the perfect discipline of the men.”10 Patterson’s ideas were massively influential. Over time, many of his senior managers left for other firms, spreading ideas about scientific sales management throughout the corporate landscape. There was one “right way” to do it. Success lay in the system, not in the individual.

Predicting Success in Sales:

Common Knowledge ≠ Compelling Results

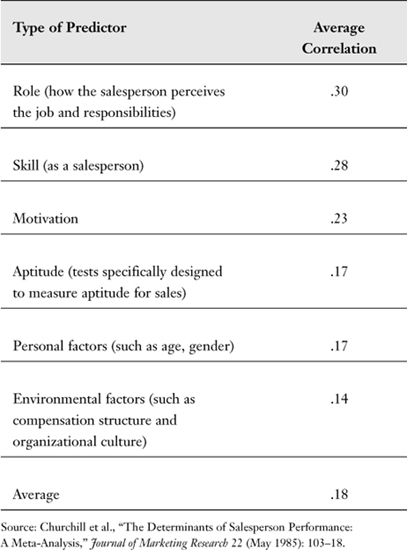

The challenge is that a century of this rah-rah conclusion about the power of passion, when compared to the research findings, begins to look tenuous, or at least overly simplistic, or perhaps just plain wrong. The literature on sales performance is large, with studies of sales performance appearing as early as 1918.11 But even decades of research seem to have yielded underwhelming results; a lack of a consistency in methods and metrics has made clear-cut conclusions difficult to obtain. In the 1980s, scientists developed ways of integrating quantitative research from a variety of studies. Called meta-analysis—literally, the analysis of analyses—these techniques allowed researchers to draw conclusions from the voluminous, if maddeningly unsatisfying, research that had been done on salesperson effectiveness.

In the mid-1980s, four business-school professors picked up the gauntlet and attempted to locate every published quantitative study of salesperson effectiveness.12 They combed through hundreds of studies, whittling down the list to the 116 most methodologically sophisticated. Beginning with the 1918 study, they analyzed studies that spanned decades and constituted an enormous collective sample. The professors concluded that the average correlation between actual sales performance and a hypothesized driver of sales performance is .18.

Let’s take a moment and put that finding into perspective. A correlation of zero means that there is no relationship between two variables. A correlation of 1.0 reflects a perfect one-to-one association between two variables—the flawless prediction of one variable from another. (Not surprisingly, a correlation of 1.0 is rarely seen in actual research.) Historically, statisticians squared correlations, multiplying them by themselves to explain the “proportion of variance accounted for.” Using this guideline, the variables that the researchers had used to predict sales success had accounted for only 4 percent of the variance in how salespeople actually performed—a dismal showing. The professors, explicitly disheartened, were forced to conclude: “The generally small size of the correlations between predictors and performance criteria is somewhat discouraging.”13 Today’s guidelines for interpreting correlations in scientific and market research are more charitable, but they still put a correlation of .18 in the small to moderate range. That is, correlations of .10 are generally considered as small, .3 as moderate, and .5 as large.14 (Correlations in the .80 range are considered as “reliability coefficients,” reflecting that the same underlying construct has been measured in two different ways.)

It’s not so much the low average correlation of .18 that’s discouraging, however; after all, it’s an average, and there were individual studies that stood out in the group as being more on the trail of identifying a profound effect. But the correlations didn’t increase over time, suggesting that research findings and theoretical advancement hadn’t been able to improve the ability to predict who would succeed and who would not. And it was discouraging to find such low correlations from measures specifically designed to predict sales performance, and many merely seem restatements of being an effective salesperson (see Table 2.1). A test designed to be a measure of salesperson skill or aptitude, for example, that correlates only .2 with actual performance is not particularly something to write home about.

TABLE 2.1

Predictors of Sales Performance

The unfortunate fact is that most investigations into determinants of sales excellence have yielded the same lukewarm results. A 2005 meta-analysis of fifty-one studies found that commitment to the organization predicts sales performance, with an average correlation of—you guessed it—the same low to middling .18 revealed by the other research.15 And again, consider the intuitive nature of the finding: Salespeople who like the organization they work for, and have an emotional commitment to it, outsell those who don’t—but only modestly.

Even more discouraging are the results from research that has attempted to connect sales performance with more “distant” variables, which would be less restatements of the seemingly obvious and more meaningful information. Literally decades of research on personality traits have been synthesized into “the Big Five”—five core dimensions of personality that have been identified consistently in research over time and across cultures: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience. Two of these dimensions consistently predict strong sales performance, but the correlations are even smaller than before.16 Conscientiousness, as measured by Big Five tests, refers to the tendency to be organized, responsible, and dependable. Studies have shown conscientiousness to be associated with hard work, determination, and being goal oriented. Surely such a personality trait would correlate highly to success in a field like sales, which often requires a self-starter who can win the trust of prospects. And it does, in the modest .10 to .20 range of variables we explored earlier. And it doesn’t just predict sales success—it has the same modest predictive power over success among midlevel managers, police officers, and semiskilled laborers. Ditto extraversion—the tendency to be outgoing and active—which correlates an even more modest .10 to .15 with sales success. There’s essentially no correlation at all between sales performance and openness to experience, agreeableness, like-ability, or emotional stability.

In short, the research shows that sales excellence is not about being male or female, young or old, likeable or cranky, cultured or crude, stable or neurotic. Successful salespeople are ever so slightly more likely to be extraverted or conscientious, but there are plenty of people in sales who are introverted or undependable. Either way, it helps if they are committed to their organizations.

Interesting? Yes. Helpful to a salesperson or a sales manager? Maybe a little. The key to sales success? Not really.

Optimism and the Pinpointing of Passion

Amid research with seemingly middling or inconsistent results, there are, nevertheless, several lines of research that converge on the central role of passion and related ideas in sales success.

One of the most notable efforts was conducted by University of Pennsylvania psychologist Martin Seligman for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in the 1980s.17 Known today as the father of positive psychology (the scientific study of happy, highly achieving people), Seligman was best known at the time as the leading researcher in human optimism. He was approached by Metropolitan Life, an industry behemoth in the 1950s that had seen its market position, and its sales force, erode over the decades. As the company had explored alternative channels of distribution, the sales force dropped from 20,000 to just 8,000 and became less effective as well. Met Life was losing $75 million a year hiring agents who would turn out to be ineffective and eventually leave. A lot of agents, in fact—5,000 a year—had been carefully screened from a pool of over 60,000. Yet half of them were quitting in the first year; 80 percent quit by their fourth year. Only a small percentage turned out to be top performers. And Met Life certainly wasn’t alone; turnover has been, and continues to be, a major problem among salespeople in the life insurance industry. But the company’s weak market position made the problem particularly pressing, and so Met life sought out Seligman to explore how an understanding of optimism might enhance the effectiveness of its sales force.

The research results were clear: Optimists outsold pessimists. By a lot. In one study, optimistic life insurance agents outsold pessimistic ones by 8 percent in the first year, expanding to 31 percent by the second year, as the power of passion and persistence began to shine through more dramatically. Follow-up studies suggested that the impact of optimism on sales performance could be even greater, particularly in the high-rejection cold-calling environment typical at the time. After nine calls and nine rejections, the optimist thinks, “The tenth call could be my next sale.” After nine calls and nine rejections, the pessimist thinks, “My life sucks.” For the latter, a cycle of avoidance and procrastination begins, spiraling into passivity and burnout. As a result of Seligman’s research, Met Life rethought its approach to hiring and training and saw its sales force and market share grow dramatically.

In fact, the 1980s and 1990s saw growing bodies of research addressing the emotional and motivational elements of sales performance. A 1998 meta-analysis on the predictors of sales excellence examined 129 studies and confirmed the modest correlations with the Big Five personality traits we described.18 But the researchers uncovered some tantalizing clues to stronger relationships as well. They divided extraversion into two subdimensions: affiliation and potency. Affiliation refers purely to one’s sociability, while potency refers to one’s impact, influence, and energy in social interactions. The studies showed that affiliation had a small impact on sales performance, but potency had a much stronger impact, with correlations in the .26 to .28 range. The researchers also divided conscientiousness into two subdimensions: dependability and achievement. Dependability had only a small impact on sales performance, while achievement was a more influential dimension, with correlations from .25 to .41, suggesting that striving for competence plays a greater role in sales success.

But the biggest predictor this research uncovered was not a personality trait but, rather, a variable they labeled simply as “interest in sales,” which correlated a substantial .50 with both sales managers’ perceptions of their sales staff and actual sales performance. (In contrast, salespeople high in “general cognitive ability”—in other words, smarts—were rated more highly by sales managers but they didn’t sell any better than their less “cognitively able” counterparts.) The predictive power in what the researchers rather mundanely labeled as “interest in sales” is both intuitive and revealing. And although it doesn’t literally use the word passion, clearly the conclusion is the same.

The case is similar for the deservedly popular research on sales effectiveness conducted by the well-known polling firm Gallup. Its signature concept, which it considers to be at the heart of excellent corporate performance (sales and otherwise), is strengths. Simply put, different salespeople have different strengths: Some are competitive, others are relationship focused, still others are excellent learners or listeners, and so on. Top sales performance, Gallup argues, is not associated with any strength in particular; instead, it comes from understanding and leveraging one’s existing strengths. The Gallup concept is more process focused and less content driven than our notion of passions, but the parallels are obvious and the conclusions are highly similar. Consider some of the take-aways from Gallup’s research, such as the role of passion as driving sales success: “Our research indicates that the happier you feel about your performance and the greater your satisfaction in your sales role, the more your customers will want to buy from you.”19 On discovering one’s passions and molding one’s environment: “The best salespeople adapt that job to suit their strengths; they do not attempt to change their strengths to suit their job.”20 On people who don’t play to their strengths: “[They] dread going to work . . . treat customers poorly . . . achieve less on a daily basis.”21

The Gallup research suggests that the end result of a job in which one can effectively pursue one’s strengths is “engagement.” Employee engagement is a strong predictor of sales performance, employee profitability, customer focus, company loyalty, and even workplace safety. The problem with employee engagement, or playing to your strengths, or pursuing your passions, or whatever language you want to use is that not enough people do it. In worldwide research with more than 10 million employees, Gallup discovered that only one in three strongly agreed with the statement: “At work, I have the opportunity to do what I do best every day.” Using a similar model, consultancy BlessingWhite concluded that only 29 percent of employees worldwide are fully engaged and 19 percent are actively disengaged (e.g., actively spreading their discontentment), with the majority stuck in something of a blah middle ground.22 The impact on the bottom line is clear: Outstanding companies average more than nine times as many engaged employees as unengaged ones, whereas average companies have a ratio of less than two-to-one.23

So what’s the conclusion? It is easy to see why the affluent are pulling back from salespeople. In most circumstances, they have only a one-in-three chance of getting a salesperson who is passionate about what he or she is doing!

LIFESTYLES OF SUCCESSFUL SALESPEOPLE

Who are successful salespeople, and what are they like on a day-to-day basis? A complementary look at successful sales-people, and additional insights into their success, come from our ongoing Survey of Affluence and Wealth in America (produced jointly with American Express Publishing, and described more fully in the appendix). For the past five years, we have surveyed Americans with at least $100,000 in annual discretionary income, including many with incomes well over $1 million. This survey provides a broad representative look at the affluent and wealthy populations in the United States. But for now, let’s examine a subset of the respondents: the roughly 5 percent who describe themselves as sales and marketing executives. They are successful indeed, averaging over $420,000 in annual income and $3 million in liquid assets. We compare them not to less successful salespeople but, rather, to other affluent individuals who have achieved a similar level of financial success in fields other than sales (see Table 2.2).

TABLE 2.2

Self-Descriptors of Successful Salespeople

First, we see that the three most commonly used self-descriptors—intelligent, loyal, and family-focused—are consistent among salespeople and those in other professions. But the broader pattern of results reveals the characteristics of sales success that we have shed light on. Salespeople are far more likely to describe themselves as competitive, driven to succeed, and winners, and less likely to describe themselves as patient. They are also more likely to describe themselves as spiritual—perhaps a surprising finding, but we have heard this in our qualitative interviews as well. For some, a sales career can become an expression of their spiritual focus and their desire to serve others. Academic research has also found that religious people tend to be happier, and happy people are generally more successful, for a variety of reasons.24

Salespeople are also more likely to describe themselves as athletic; this may reflect their sense of competitiveness as expressed in other domains, although it may play a more direct role as well, as exercise is associated with persistence, goal accomplishment, stress reduction, and overall mood. Their interest in sports is extensive and wide ranging, including firsthand participation, television viewing, and attendance at sporting events (see Table 2.3). Their profile of preferred activities also reveals that, at the risk of reaffirming stereotypes, salespeople are slightly more likely to regularly drink alcoholic beverages (50 percent vs. 43 percent), gamble (24 percent vs. 17 percent), and play golf (9.6 average rounds per year vs. 6.6). The stereotype of the frequently traveling salesperson is safe as well. They average sixteen to seventeen nights in hotels annually for vacations, just like their non-sales counterparts, but they average 10.5 business trips a year with over twenty-three nights spent in hotels compared to averages of 4.9 business trips and 12.5 business hotel stays for the affluent population as a whole.

TABLE 2.3

Leisure Activities of Top Salespeople

DISCOVER YOUR PASSION AND

MOLD YOUR ENVIRONMENT

Your personal sales success is about discovering the passion within you and choosing and molding your environment to fit that passion. It’s about finding ways to express that passion that fit with your personal style.

Passion transcends personal style. In fact, it morphs and manifests itself differently in different people, depending on personal style. When we interviewed top performers at the luxury auto dealership described earlier in this chapter, we were struck by the variety of passions that could be expressed through top sales performance. One person simply had a passion for winning, for topping the company sales charts each year. Another had a passion for the Internet and had built a thriving customer base through savvy search-engine optimization and eBay sales.

Another individual had a passion for the outdoors, so he turned his hunting and fishing hobbies into opportunities to network with those who had similar passions, thereby making himself one of the most successful Hummer salespeople in the country. (And, in an adaptive selling approach characteristic of the highly passionate, he has proactively been keeping his clientele satisfied with other brands now that Hummer is defunct.)

Yet another top performer found a way to satisfy his deepest passion through his work: “I’m a spiritual guy. I believe in serving other people. That’s all we do—we’re just servants. If I serve you the way you want to be served, you’re going to be so excited about that. I don’t even have to ask you to buy a car from me. I don’t have to ask you to send me a referral.”

The notion of finding an environment to fit one’s preexisting interests and mindsets is both very old and very new. Consider an 1890 corporate newsletter of the Singer Manufacturing Company, a sales powerhouse of its day, that contained the following aphorism: “If the salesman cannot bring himself to believe in himself, his house, and his goods, he is either very badly placed, or he has mistaken his calling.” Identifying a job that fits well with your skills and further molding the job environment to strengthen that fit still works today. We—the authors of this book—have different passions: writing, speaking, the intellectual challenge of complex research, selling new projects, building the business, and so on. We work together at the same company, but we have found ways to structure our individual jobs so that we can focus primarily on our individual passions. It isn’t always easy, and sometimes it requires restructuring our workdays, our staff, and our division of labor among ourselves. But we persist in finding ways to strengthen the fit of job and skill, as that has proven to be the key to both professional success and personal happiness.

Most sales training efforts have been unsuccessful because they have focused on molding the individual to fit the system. Certainly some of that needs to be done; sales-people must understand the product line, communicate their brands in a consistent manner, understand the corporate culture, and so on. But ultimately it’s about finding what interests you and then choosing or molding environments appropriately. Done with too much drive, it can be off-putting. Excessively molding (some might say manipulating) one’s work environment can come across as overly self-serving and be perceived as disrespectful of the corporate culture and one’s coworkers. That’s precisely the complaint one colleague had about Ross Perot: “The problem I had with Perot is that if the game doesn’t go the way Ross wants it to go, he keeps trying to change the rules so that he wins.” But ultimately, taking charge of their environment, and bending it to their needs, is one way that highly successful people come to thrive.

University of Montreal psychology professor Geneviève Mageau summed up her research on the topic this way: “Passion comes from a special fit between an activity and a person. . . . You can’t force that fit; it has to be found.”25 One of her studies found, for example, that kids were more likely to develop a passion for music if they were given the autonomy to structure how they would approach music—choose their instruments, their genre, their practice schedule. Interestingly, although some kids in less self-chosen environments became passionate about music, they were more at risk for showing an unhealthy obsession rather than a productive and thriving passion.

* * *

The take-away: Sales managers must rethink their roles in a discover-your-passion-and-mold-your-environment world. Their job becomes less about managing and more about unleashing. It’s less about enforcing rules and more about helping people creatively bend them. This is particularly true because many salespeople are attracted to the field in large part for the autonomy it provides.

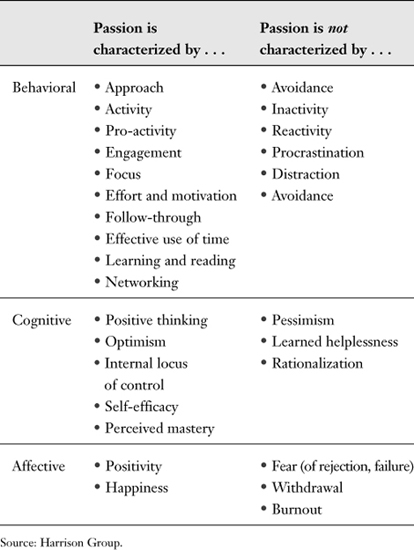

The Labels and Expressions of Passion

The label itself doesn’t particularly matter: positive thinking, optimism, engagement, leveraging strengths. We use the word passion. These are all expressions of the same underlying phenomenon. And let’s be clear: We’re not advocating an effortless “get passionate and success will come” philosophy. Passionate people achieve more because they think differently, they act differently, and they even feel differently from the rest (see Table 2.4).

TABLE 2.4

Behavioral, Cognitive, and Affective Manifestations of Passion

Passionate People Are Magnetic

Passion is easily apparent. Everyone can literally see it—quickly. Harvard psychologist Nalini Ambady found that a 30-second video clip of sales managers discussing their work is enough for people to accurately distinguish the top sales managers from the average ones.26 In fact, people do even better at this task if the verbal content of their statements is filtered out, allowing observers to ascertain only body language and tone of voice. Actually listening to what the people say, it turns out, gets in the way. Dr. Ambady and her team suggested that observers are picking up on strong interpersonal skills, and they assume those skills lead to enhanced job performance. That certainly plays a role, but we believe that observers are also picking up on the sales managers’ passion for their work and for life. We asked a man who had sold over $1 billion in real estate what he thought was the secret to the success of top salespeople. He responded: “It’s not just about a passion for the job. It’s about a passion for life. They have an energy. People want to be around them.”

Passionate People Learn More Effectively

Passionate people bring a fundamentally different approach to learning, and in how they respond to challenging situations. For example, social psychologist Carol Dweck and her colleagues have shown that people with a learning orientation, which focuses on acquiring new skills and mastering new situations, tend to achieve more than people with a performance orientation, which focuses on demonstrating competence and avoiding perceptions of incompetence.27 In other words, some people pursue things because they love them, want to learn more about them, and master them. Others are more externally motivated.

The results are clear: Salespeople with a learning orientation set more ambitious goals, work harder, plan better in approaching their sales territories, and more thoughtfully prioritize which accounts to pursue, and as a result, they outsell those with a performance orientation. And when the going gets tough (and in sales, that’s a regular occurrence), the reactions of the two groups couldn’t be more different. People with a learning orientation consider challenges as an opportunity to grow, to develop, to further their sense of mastery. People with a performance orientation avoid challenging situations, and when forced to confront them, they bring a “playing not to lose” approach; they prefer the certainty of an easy win, and they fear that struggling in a challenging situation will cause others to think negatively of them.

Passionate People Are Hardworking and Resilient

Passion goes hand in hand with persistence, determination, and high levels of effort. A lack of passion usually means being derailed by minor setbacks and giving up easily. It’s true in life, and it’s particularly true in sales, where many jobs are filled with rejection. Popular sales books are filled with inspiring anecdotes and motivational tales of great persistence. Some point to Thomas Edison, whose 1,093 patents remains a record, and they cite his famous remark that success is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration (or, if they are more quippy, “Everything comes to him who hustles while he waits”). Others tell the story of Mark Victor Hansen and Jack Canfield, who were supposedly unable to sell their book idea to the first 123 publishers they approached. Their Chicken Soup for the Soul and its many sequels have since sold literally tens of millions of copies (although the story is often told with an insightful twist; they got all those rejections in a single day at a publishers conference).

The importance of passion and persistence is why many popular sales training books are equal parts sales training and motivational self-help manuals. In addition, popular self-help gurus such as Tony Robbins, Zig Ziglar, and Brian Tracy all have strong contingents of salespeople among their fans, and they all have books, audio programs, and seminars specifically targeted to salespeople. Whatever one may think of today’s crop of motivational gurus, it is hard to argue with the fundamental truth that passion and persistence are crucial to success in life, as well as in sales. For example, people who successfully maintain their New Year’s resolutions for at least two years report an average of fourteen slips or setbacks during that time.28 They succeed, but only because they persist.

Passionate People Fine-Tune Their Strategies

Albert Einstein is frequently credited as defining insanity as “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.” Passionate people are persistent, but they also fine-tune their strategies for pursuing their goals—in other words, they are resilient and flexible. This is precisely what effective salespeople do as well. In the research literature, it’s called adaptive selling behavior (ASB), and it’s been shown to improve sales performance in a variety of studies.29 It requires first a recognition that different approaches are needed for different prospects. But it also requires a confidence in your ability to pull it off, which is helped by practice and experience. And it often requires additional research, in understanding both the unique interests of the prospect and the different ways you can deliver what would meet his or her needs. As always, it starts with interest and passion, but it only impacts bottom-line performance with practice and hard work. Nevertheless, it’s worth the effort. So take a moment to revisit how you might be able to adjust your sales strategies in specific situations, based on what’s working and what’s not. For example:

• Phone calls not getting through? Try e-mail.

• The customer doesn’t want à la carte pricing? Put him on a retainer.

• The customer isn’t picking up on your usual subtle hints about when orders need to be submitted? Try being a little more blunt about timelines.

Passionate People Move Toward Desired Outcomes

People of passion set goals more effectively, resulting in them feeling “pulled” toward their goals as opposed to pushing themselves. Their success comes, in part, from knowing what they want to pursue, not simply what they want to avoid. Psychologically, this distinction is crucial. People who focus on moving toward desired outcomes, as opposed to setting “avoidance goals,” are:30

• Physically and psychologically healthier

• More satisfied with their lives and their relationships

• More committed to their goals

• Less upset after setbacks, and more resilient after setbacks

• Characterized by a sense of autonomy and control over their lives

• Happier when they eventually achieve their goals

• More mentally focused on positive memories and triumphs

• Characterized by a “want” mindset, rather than a “should” mindset

Passionate People Live Better

The power of passion even goes beyond something as fundamental as goal setting. It impacts every aspect of life.31 People with a clear, compelling, nonconflicted view of what they want in life are happier. They are more satisfied with their lives. They take action more and ruminate less. They do better in school. They achieve more in their careers. They experience less depression and anxiety. They have better physical and psychological health. They are more successful at making life changes, such as losing weight or keeping New Year’s resolutions. They are characterized by a strong sense of honor, solid values, and deep integrity.

That’s quite a list.

THE NEXT STEP

It should be pretty clear by now: Discover your passions. Rediscover lost ones. Pursue them. Indulge them. Follow where they lead you. If you aren’t passionate about your job, then get passionate. Improve the fit, or get a new job. Seriously.

And read the next chapter, which discusses the second passion that defines successful interactions between the affluent and those who sell to them.