CHAPTER ONE

The Desire to Acquire

“We can do without any article of luxury we have never had;

but when once obtained, it is not in human nature to

surrender it voluntarily.”

—THOMAS CHANDLER HALIBURTON

CHIMPANZEES LIKE PEANUT BUTTER as much as they like frozen juice bars.

That may seem an odd place to begin a book about selling to the affluent. The equivalent preference for two disparate monkey snacks is seemingly far afield from the topic at hand. But in fact, this conclusion about equal primate desires for peanut butter and frozen juice, gleaned from several studies, is actually a useful starting point in understanding a variety of sophisticated human behaviors, including the purchase of luxury products. It turns out that some human behaviors are so deeply ingrained in what we might offhandedly think of as human nature that, in fact, they transcend humanity itself. And so it is with the desire to acquire.

As scientists tend to do, primatologist Dr. Sarah Brosnan at Georgia State University introduced an interesting twist to an otherwise well-understood situation. Instead of letting the chimpanzees choose their own snacks, she gave some chimps peanut butter, and then gave them the opportunity to trade their peanut butter for a frozen juice bar. Given the 50/50 preference mentioned, one might expect that half the chimps would make the trade. That is, some might characteristically prefer one over the other, or maybe it would depend on what they were “in the mood for” at the given moment; regardless, the equivalent preference for the two should be consistent. But it’s not. In fact, 80 percent chose to keep their peanut butter. The same was true for frozen fruit bars, if a little less dramatically. Handed an icy treat, about 60 percent of the chimps preferred to keep it—again, significantly different from the 50/50 split observed, once “ownership” is taken out of the equation.

It’s been called “the endowment effect”—the tendency to value something more when your ownership of it has been established. And as you can see, the phenomenon transcends human behavior; it would appear to be deeply engrained in the DNA of our primate cousins as well. Its impact on human behavior is profound yet subtle. And its effects are observable not just in the scientist’s laboratory, but in everyday behavior as well.

When it comes to rounding up participants for psychological research, college students are an even more popular source than chimpanzees. Besides an enthusiasm for free food, chimpanzees and college students share a tendency to display the endowment effect. In fact, replace tubes of peanut butter with chocolate bars, and replace frozen juice bars with coffee mugs, and the behavior of chimps and college students begins to look surprisingly similar (or, perhaps not that surprisingly, depending on how much time you’ve spent on a college campus). When given a choice of a coffee mug or a chocolate bar, college students express no strong preference for one over the other. But given a chocolate bar, well, good luck if you’re in the business of handing out mugs; the students will stick with their chocolate. The opposite is true as well: Given a coffee mug, they prefer to hold on to it, rather than trade it for a supposedly equally desired chocolate bar.

For a while, this element of human (and occasionally nonhuman) behavior seemed poised to upend several tenets of classical economic theory. Built on a “rational actor” model of human behavior, one aspect of economic theory posits that a person’s “willingness to pay” for a good should be equal to his or her “willingness to accept” compensation to be deprived of that same good. Debates in academic journals heated up. A flurry of studies dug into the issue in tremendous detail. Some questioned the robustness of the original findings. Others explored the boundaries of the phenomenon, delineating the precise circumstances under which it occurs. But in counterintuitive ways, even these studies seemed to reinforce how “primal” the endowment effect is. Among chimps, for example, the endowment effect occurs with food, but not with “abstract” objects such as rubber bones and knotted ropes. Primatologists believe this means that the power of ownership evolved to help aid survival itself. As Dr. Brosnan put it, “Giving up something that could help with survival or reproduction may have been so risky that it wasn’t worth doing even if there was the potential for something better.”1

Other studies picked apart the fine distinctions between the endowment effect and related phenomena. But again, more often than not, in practical circumstances, these behavioral tendencies likely reinforced the power of the endowment effect, not lessened it. “Loss aversion,” for example, is the well-documented tendency to avoid losses more vigorously than seek out gains. That is, losing $5 (or $500,000) is more painful than gaining the same amount is pleasurable. One study reported that when salespeople raise the cost of insurance policies (a painful loss of money from the insured’s point of view), consumers are highly motivated to begin price shopping and look to change insurance providers. But when costs are lowered by the same amount (from the consumer’s point of view, a gain of money), the impact in terms of improved satisfaction or loyalty is much smaller.2 Loss aversion may be subtly different from the endowment effect, but in most practical circumstances, the two will work together, making the desire to acquire and the proclivity to accumulate stronger and more prevalent.

Over time, the endowment effect—that curious power of ownership—came to be accepted as one of many “irrationalities” at odds with a perfectly rational representation of human choice (particularly if, as is often done in such discussions, the assumption of rationality is taken to straw-man extremes). The field of behavioral economics emerged as the scientific study of “anomalous” human consumptive behavior; economics broadened in its explanatory power rather than shrank.

While economists struggled to make sense of the seeming irrationality of human behavior, salespeople and marketers embraced it, and they have historically made understanding these quirks a central element of their professions. Consider that staple of infomercial selling—the free trial. Once you own something, you value it more. You get used to it. You embrace its strengths. You begin to look back on your decision to buy (or, more technically, to try with the potential for buying later) with pride in your smarts and resourcefulness. The thought of parting with it is sad and brings to mind all the potential circumstances and consequences of loss. In short, it’s loss avoidance and the endowment effect together, with probably a handful of related concepts thrown in (including the desire to avoid the hassles associated with returning products and the reluctance to break what feels like a binding social contract).

Consider the following business-meets-primatology thought experiment. A community of chimpanzees characterized by the free choice of snacks has two products (juice bars and peanut butter), each with 50 percent market share. Senior management at Chimps Ahoy Peanut Butter arm their sales force with free trial packages and a compelling sales pitch: “Just try our peanut butter, Mr. and Mrs. Chimp; if you want to keep it, you can pay me later. And if you decide you want to trade it for a frozen juice bar, just let me know, and I’d be happy to make that trade for you. But I think you’ll be really happy about your decision to stick with Chimps Ahoy.”

The bottom line is this: People like stuff. They buy stuff. They accumulate stuff. They don’t particularly like to get rid of stuff. It is deep in our DNA. It is so primal as to predate humanity itself.

THE ESSENCE OF SELLING: CHANNELING

VS. CREATING THE DESIRE TO ACQUIRE

There are, in our opinion, many myths about selling and salespeople, such as:

• A great salesperson can sell anything.

• The best salespeople make the best sales managers.

• Anyone can be turned into a great salesperson.

We’ll explore these and other myths in this book, but for now, we tackle one of the biggest: Salespeople get people to buy things they don’t want.

The desire to acquire is fundamental; the salesperson’s role is more about unleashing and channeling that preexisting desire than it is about forcing unwanted items on susceptible prospects. There are, of course, exceptions. Boiler rooms of high-pressure telephone salespeople hocking fraudulent investments do exist. (Speaking of which, anyone reading this book would likely find the movie Boiler Room an interesting look at the seedy hard-sell underbelly of the stock brokerage industry. Admittedly imperfect and dramatically flawed as a film—that is, a bit lame—it’s worth the viewing not only for its recognizable portrayal of a high-pressure sales environment but also for Ben Affleck’s hysterical turn as a low-rent version of Alec Baldwin’s coffee-is-for-closers sales guru from Glengarry Glen Ross.)

Like so many myths, this one has its origins in commonplace reality, as for generations most salespeople had to close the sale immediately. Peddlers and merchants have been around as long as society has existed, traveling from community to community, seeking to maximize their sales from each person and each town before moving on to the next. They were the traveling Wal-Marts of their day, albeit with smaller selections, and they sought one-shot “transactional” sales. They would be moving on soon, and so they were not focused on building long-term relationships. Their visits were anticipated, their goods were highly sought, and they were one of the biggest distribution channels of the time. But high-pressure tactics were not uncommon, satisfaction after the sale was often low, and the peddlers’ reputations suffered as a result. In 1800s America, their numbers boomed, particularly after the Civil War, as former soldiers and waves of new immigrants sought entry-level positions where they could be their own bosses.3 At the same time, the industrial revolution was increasing the supply of goods, and the return of a peacetime economy was spurring demand. For many, traveling merchant seemed the best path to the American Dream of the time, but the image suffered. These peddlers and merchants were often portrayed in popular culture as swindlers. Jokes were told about dishonest and ineffectual traveling salesmen. Given the frequency with which peddlers called upon farmers in the agrarian society of the day, the jokes often involved a traveling salesman and a farmer’s daughter. Admittedly, much of this negative word of mouth was spread by shopkeepers in general stores—direct competitors to the peddlers. Regardless, there seemed to be enough truth in the gossip to perpetuate the image. It’s a black eye that continues to endure today.

* * *

Salespeople have a decades-long history of being ranked at the bottom of “Whom do you trust?” survey questions, along with politicians and advertising executives. And as the peddler profession faded away, other sales professionals came to bear the brunt of the antisales sentiment. Perhaps auto dealers have had it worst, and again, there was some kernel of truth that perpetuated the negative stereotypes. After World War II, cars were in short supply; auto factories had been converted to munitions factories and other sources of support for the war effort. At the same time, demand for cars skyrocketed. Soldiers returned home and wartime rationing ended, encouraging consumption of all types. The American Dream evolved with a car soon becoming a central part of it. The emergence of suburbia necessitated the widespread adoption of cars. Soon a luxury was becoming a necessity, but one that retained its position as an emotion-laden aspirational purchase as well.

All of these factors combined in the emergence of a transaction-focused environment. High-pressure sales techniques came along as a result. The simplicity of sticker prices was replaced with complex negotiation; experience and knowledge ensured that the salesperson would have the upper hand. The auto industry developed a bad reputation that remains today, even after the emergence of fixed-price dealerships and an Internet world that has largely corrected the power and information imbalance that once characterized the salesperson-prospect relationship.

But at some level, even boiler rooms and the most nefarious stereotypical car salespersons aren’t creating the impulse to purchase; they are simply channeling the desire in their selfish direction via unethical ways. Boiler rooms are selling financial gain, competing against other investments; auto salespeople are trying to win a sale that might otherwise go to the dealership down the street. Particularly when we are talking about affluent individuals and luxury markets, it’s less about motivating the desire to purchase and more about winning market share by channeling consumption in the direction of you and your brand.

Again, there are exceptions, particularly when the Great Recession caused consumers both rich and poor to cut back significantly. For example, in 2009, a luxury auto dealership asked us to train its sales associates in dealing with a new phenomenon: prospects deciding to not purchase a car at all. As one salesperson explained it, “I’m losing fewer deals to other dealerships; instead, people are just buttoning their wallet and waiting.” But even under extreme circumstances, such as the average affluent person’s losing 30 to 40 percent of his or her portfolio at the deepest point of the recession, the decision to not purchase was less common than were value-seeking behaviors. Some put their loyalty to the dealership aside in their quest for a better deal. (Again, to quote one of the sales associates, “Customers who never shopped me before are shopping me now.”) Others opened their minds to trading down in quality. (“Nonluxury cars are entering my prospects’ consideration set in ways I haven’t seen before.”)

Even the decision to not purchase was, in actuality, a decision to not purchase right now. Before the recession, half of the affluent stated that they “tried to buy a new car every two to three years,” but as the recession wore on, that figure dropped to one-third of the affluent. Still, for most, that simply meant a four-year replacement cycle, not a decision to keep their current cars till they pass 100,000 miles.

THE DESIRE TO ACQUIRE . . .

SOMETHING NICE

The urge for acquisition is innate and fundamental. So is the urge to acquire something nice. Archeologists often point to the emergence of cave art and symbolic representation as the hallmarks of “fully modern” humans, but much of the earliest art and craftsmanship was in the form of more personal objects—objects that, we can only assume, held deep personal meaning for those who made them: small statues, talis-mans, jewelry, weaponry crafted with elegance and symbolism that transcended utilitarian need. The list goes on. Today, we might call it luxury, although that word is rife with connotations that may not apply. Acquisition of “luxury” is less about conspicuous consumption and more about owning something of beauty and meaning, of refinement and sophistication. As we shall see, acquisition of luxury means owning or experiencing something exceptional, something created with a true sense of passion and artistry, something that can provide a truly sublime experience. Understanding these motivations is, obviously, crucial to success in selling to today’s affluent and wealthy.

The desire for luxury in this sense is nearly universal, and once the cost and availability barriers are brought down, the acquisition of those former luxuries becomes nearly universal as well. Consider the culinary examples. Sugar. Spices such as pepper. Coffee. Chocolate. Silverware. All started out as expensive and rare treats for a select few monarchs and slowly diffused their way through the wealthy aristocracy before eventually entering into mainstream use.

The desire to acquire something nice—luxury, if you will—is so profound that societies have often felt threatened by it and have tried to control it.4 But in a testament to the power of this desire, those societies have almost always fought a losing battle. In the end, societies usually end up embracing this fundamental human urge. Plato tells of Socrates’ admonition that the best life is a simple one, with only what is necessary in terms of clothing and food. (“Many men live to eat; I eat to live.”) Further, Plato reasoned, a society in which people conduct themselves in this way will live both peacefully and prosperously. But a “luxurious” society, in which desire and acquisition run amok, he poetically describes as an “inflamed” or “fevered” one. That is, the need to meet society’s growing appetite (literally and figuratively) requires ever more resources, ever more territory, more of everything. Plato viewed it as a cultural double-whammy—the aspiration to luxury enhanced the desire to grow territory through warfare, but that same luxurious lifestyle was thought to make people soft, effeminate, even emasculated.

The Greeks were great thinkers. And their thoughts about wealth, luxury, and refinement reverberated through the centuries. The Romans were great doers and lawmakers, and they translated Greek philosophical theory into institutionalized practice. Rome was, of course, home to fabulous and highly concentrated wealth as well as a wholehearted pursuit of “luxury” (although “opulence” and “extravagance” might better capture the spirit of the times). Like Plato, the Roman philosophers preached that the life of desire destroys the individual and destabilizes society. As the Roman poet Juvenal put it,

Now all the evils of a long peace are ours;

Luxury, more terrible than hostile powers,

Her baleful influence wide around has hurled

And well avenged the subjugated world.5

Like the Greeks, the Romans also thought a life of luxury had a negative, feminizing effect. But they blamed its presence less on universal human nature and more on the insidious effects of other cultures. Xenophobia ran deep—as Rome conquered more Asian territory, for example, there was fear that the refined “effeminate” sensibility Asians supposedly had toward luxury would infect the troops and return to the Roman homeland with them. In fact, the Romans had such respect for the power of luxurious desires that they even used them as a weapon of war. Tacitus tells that the Roman governor of Britain attempted to calm potentially disruptive townsfolk by getting them hooked on “rest and repose through the charms of luxury.” He started with the sons of local chiefs, introducing a lifestyle through which “step by step they were led to things which dispose to vice, the lounge, the bath, the elegant banquet.”6

The Romans managed their societal fears with a typically institutional approach. The office of the Censor was charged with legislatively managing Roman lifestyles, and when Cato the Elder was elected Censor in 184 BCE, he made stamping out the evils of luxury job number one. In today’s terms, high-end products were assessed at very high prices, and luxury taxes were introduced to diminish the enthusiasm for high-end consumption. We might not relate to the currency they used, but the overall approach sure feels familiar: “The assessors were ordered to list jewels and women’s dresses and vehicles which were worth more than 15,000 asses at ten times their value . . . and on all of these items a tax of three asses per thousand was to be collected.”7

Today we’d call this sumptuary legislation, and it is found in the history of many cultures around the world. The English built on the Roman heritage, and in the 1300s they passed laws dictating what kinds of food and clothing were appropriate for each of seven “clauses” of individuals. A “Clause I” person (such as a servant) could wear only the simplest of clothing, while a “Clause V” knight whose lands yielded over 200 pounds could wear clothing worth up to six marks, provided it had fine embroidery. These laws reduced consumption, provided stability to the social structure, and protected domestic merchants from competition from “luxury” providers in other countries.

As Rome fell, luxury took the blame. Sumptuary laws, so the narrative of the time went, were ultimately ineffective, and Rome was dragged down by the pursuit of desire and the supposed weakness and social disruptions thought to result from it. Even the rugged Spartans came to be viewed as having been dragged down by luxury. As the Roman era gave way to the Dark Ages, things got even worse for luxury, going from scapegoat of the Roman decline to the very essence of evil.

The medieval poem Psychomachia, for example, describes a grand battle of good versus evil in various guises: Christian Faith versus pagan gods, Chastity versus Lust, Patience versus Anger, and Pride versus Humility. Then Luxuria arrives in a gold- and jewel-encrusted chariot (today it would probably be a bling-encrusted Bentley). She attacks with violets and roses, weakening, effeminizing, seducing even the virtues who won previous rounds of the battle. But Good mounts a comeback, and Temperance arrives to finally kill Luxuria in a scene that would likely guarantee an R-rating if it were faithfully reproduced on the big screen. Still, the point is clear, and the characterization of luxury was cemented for centuries. In fact, Luxuria quite nearly made it to the final list of seven deadly sins, only to be replaced by lust. For centuries, the words “luxury,” “lust,” “lechery,” and “lewdness” became largely interchangeable.

As the Dark Ages gave way to the Renaissance, and free enterprise began to emerge throughout Europe, many influential thinkers began to have a change of heart about luxury. Sure, it could still make individuals weak, they argued, but perhaps it could have positive benefits for society as a whole. After all, highly skilled jobs were created, and a new class of artisans and craftsmen emerged; it was trickle-down economics centuries before that term would be coined. Some began to question whether luxury was really associated with effeminacy; various fighting forces were pointed out to have fought bravely despite an affinity for puffy shirts and powdered wigs. Even the fall of Rome came to be viewed as resulting from poor governance rather than desire run amok.

But the full-fledged rehabilitation of the “desire to acquire” came with Adam Smith, whose book The Wealth of Nations would become the intellectual blueprint for the industrial revolution and for modern free enterprise. Central to Adam Smith’s thinking was the notion that the desire for improvement was fundamental to human nature—improvement in one’s life in general, and in one’s material standing in particular. Opulence, in his thinking, was a sign of success, social mobility, and a generally healthy society. Sumptuary laws were unnatural and counterproductive; countries using them were poor and stagnant. In his words, every man was a merchant, motivated by profit and loss. Today we might say that everybody is a salesperson: Regardless of formal profession, everybody is selling something, even if it is just himself or herself. Adam Smith was a nineteenth-century “Gordon Gecko meets Tony Robbins,” combining a “greed is good” attitude with a relentless enthusiasm for self-improvement. Luxury, again in the broad sense of acquiring something sublime, had begun to shed its millennium-long bad rap and was beginning to be appreciated for its positive attributes.

* * *

Acquisition and luxury had found their philosopher in Adam Smith. But just as the Romans implemented the ideas of the Greek thinkers, it would be the French under Louis XIV who would put Smith’s philosophy into action, and luxury would begin to take its fully modern form that we would recognize today. Known as the Sun King, he converted Louis XIII’s hunting lodge in the Palace at Versailles, and under his 1643–1715 reign, fashion, architecture, interior design, and furniture would all be revisited and rethought with an eye toward an opulence that transcended utility. A few decades later, Marie Antoinette would famously frequent the many purveyors of luxury goods that had sprung up and increasingly come to define the economic culture of Paris. They came to define the psychological culture as well: elite goods reserved for a wealthy few, aspired to by many, but widely resented as well. Reminiscent of the Roman admonition that luxury would destabilize society, the inequalities of the time sparked the French Revolution, and although Marie Antoinette didn’t survive it, surprisingly the enthusiasm for luxury largely did. Within less than seventy-five years after the egalitarian-striving revolutionary upheaval, a new breed of merchants built on this surviving enthusiasm for luxury and opened businesses in Paris. Many of the names we still recognize today: Hermès, Cartier, Louis Vuitton. The desire to acquire, both the everyday and the refined, is deep and resilient, indeed.

SO WHAT’S THE PROBLEM?

THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE IN SALES TODAY

The biggest challenge in sales today is not a lack of consumer desire. Indeed, our brief review of history shows that the desire to acquire extends beyond human nature, and has rarely been stamped out, despite many attempts by many societies. It has been a challenge for governments seeking to maintain the status quo, and for philosophers who feared that luxury would destroy the moral fabric of society. But for merchants, marketers, and salespeople, greater challenges lie elsewhere. Even as the economic downturn of the later 2000s drags into a new decade, the desire to acquire remains profound and fundamental. More restrained than in 2005 or 2006, to be sure, but as we have seen, it is still there and still powerful.

The biggest challenge in sales today, particularly as it pertains to the affluent, is this: Customers have stopped listening. In increasing numbers, affluent consumers have stopped seeking out salespeople. They rely on salespeople less. They increasingly go to the Internet to avoid salespeople altogether.

Why? The unfortunate truth is that most salespeople aren’t very good. The promise of a great sales experience is remembered fondly from the past, but it is being fulfilled with increasing rarity today. For example, in 2007, our annual Survey of Affluence and Wealth in America, produced with American Express Publishing, found that two-thirds of the affluent agreed with the statement: “I depend on the salesperson to know the specific details of a product that makes it worth more.” By 2010, that figure had dropped to 49 percent. In 2007, 39 percent agreed with the statement: “I have close relationships with a few salespeople that I count on,” a figure that dropped to 25 percent by 2010.

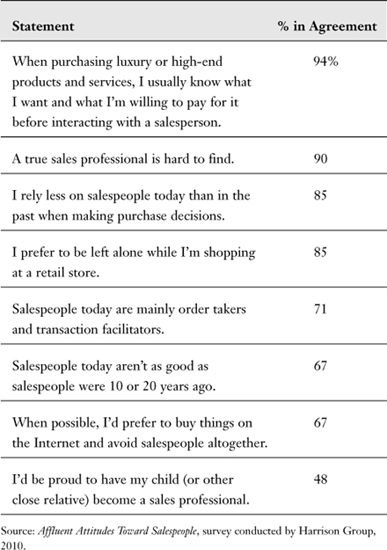

Our 2010 Affluent Attitudes Toward Salespeople survey, conducted among consumers earning more than $125,000 per year, led to similar conclusions about the declining influence of salespeople (see Table 1.1). Slightly more than nine in ten customers have largely made up their minds about what they want—and what they’ll pay—before a salesperson enters the equation. Nearly as many agree that a true sales professional is hard to find, and that salespeople are less influential in their purchase decisions than they used to be. On the whole, today’s salespeople are viewed as order takers who simply aren’t as knowledgeable or as skilled as salespeople in the past. The result is that most people would rather avoid interacting with the salesperson completely, preferring to shop on the Internet when possible and wanting to be left alone when they do venture into a retail store.

TABLE 1.1

Attitudes of Affluent Buyers Toward Salespeople

USING THE THREE PASSIONS

TO ACHIEVE SALES SUCCESS

Our research not only has revealed widespread dissatisfaction with the state of sales today but also has explored the opposite side of the equation. That is, we have studied excellence. We’ve developed training programs for selling $1,000 fashion accessories, $5,000 suits, and $10,000 handbags; $100,000 automobiles; $1 million pieces of jewelry and $5 million homes; $10 million private jets, and investment services for those with $50 million. At each stop, we interviewed the top performers to learn their best practices, and we helped hone their skills. We’ve helped them find more qualified prospects, increase their conversion rates, and drive business growth. We’ve helped many salespeople become wealthy themselves, but, even more important, become happier and more fulfilled in their jobs.

We have also studied hundreds of mutually satisfying interactions between salespeople and customers. The best of these interactions—those that are meaningful to customers and profitable for companies—are consistently characterized by three distinct sets of passions. Each is a story rife with lessons for anyone in any profession who aspires to achieve more. But understanding the three passions is not a nice-to-have, cherry-on-top self-help gift you’ll get from this book. Instead, understanding these three passions is fundamental to reengaging interest in working with salespeople (see Figure 1.1). It is fundamental to answering the question at hand: How does one more effectively sell to affluent individuals?

FIGURE 1.1

The Three Passions for Sales Success

1. The Passion of the Salesperson. Sales success comes not to dabblers and dilettantes but to those with a true love of what they do. They have found that having a sales position fits well with their interests and goals, and they have customized that position to suit their style. Success comes to them in part because they are so happy doing what they do; similarly, prospects are happy to interact with them and feel good about spending money based on their relationships with them. We’ll present stories of the world’s most successful salespeople and discover that the “secrets” to their sales successes transfer readily to other professions and domains of life.

2. The Passion of the Prospect. Our research has found that most wealthy individuals became wealthy not by aspiring to wealth per se but by pursuing a personal passion. They came from middle-class backgrounds, worked hard, and achieved financial success through corporate leadership or entrepreneurship. Over 90 percent created their own wealth. The results are prospects with middle-class mindsets and a strong value orientation that has intensified with the economic downturn, creating obvious challenges for salespeople. But these prospects understand a sales appeal based on passion; they respect people who have passions; and most important, under the right circumstances, they are willing to pay for expressions of passion.

3. The Passion of the Product. In most product and service categories, there is a quality and price level far above the mainstream offerings. This is luxury—the point at which details transcend mere excellence to create a sublime emotional resonance. These details might be in the materials, or in the history of the brand, or in the craftsmanship or design; the luxury product has been created with a passion that exceeds utilitarian need and expresses true emotion for the product. Similarly, service, and luxury service in particular, is delivered in a manner that surprises and delights, and that brings about an emotional response that exceeds practical need. We’ll explore the stories behind some of the world’s unique and exquisite products—those that have stood the test of time as exemplars of functional excellence and artistic expression—and identify how the passion implicit within them is in fact the key to selling them.

In the next three chapters, we explore these passions—these areas of success—that characterize the most mutually satisfying interactions between salespeople and their customers. Then, in the chapters that follow, we explore easy, effective, proven ways to bring these three passions together in the selling context.