CHAPTER THREE

The Passion of the Prospect

“A man without passion is only a latent force,

only a possibility, like a stone waiting for the blow from

the iron to give forth sparks.”

—HENRI FRÉDÉRIC AMIEL

“If I were to wish for anything, I would not wish for wealth

and power, but for the passionate sense of what might be.”

—SØREN KIERKEGAARD

PASSION IS MORE THAN just the defining element of top salespeople. It is also the predominant characteristic of financially successful people; in fact, for most of them, pursuing a passion other than money has been the driving force behind their financial success.

This observation may come as a surprise to some, who might be tempted to think that the highly successful are primarily motivated by money. When we began our research on the financially successful back in 2005, we also looked into how marketers and the general population felt about the affluent. We discovered that there are as many myths about the affluent as there are about salespeople. The average American, for example, views wealthy people as something akin to Mr. Burns from The Simpsons—old, greedy, unconstrained by any sense of morality or public good. Our study American Attitudes Toward the Wealthy showed that the vast majority believe the wealthy are self-indulgent, lucky, self-serving snobs (see Table 3.1).

Most people we surveyed believe that the wealthy have inherited their money, a picture reinforced not only by the Rockefeller caricatures in pop culture (including Mr. Burns and Donald Duck’s miserly uncle Scrooge McDuck) but also by celebutantes such as Paris Hilton. These archetypes of American wealth get more than their share of screen time, but they aren’t terribly representative of the wealthy. The lives and lifestyles of the financially successful are, in reality, quite different. For instance, over 95 percent of the affluent and the wealthy have created their own wealth. Most created their wealth relatively recently, with the vast majority of American wealth having been created in the past two decades. And as a result, most are still learning how to deal with the pleasures and challenges of abundance.

TABLE 3.1

How Americans Describe the Wealthy (% surveyed)

Most of the financially successful grew up in the expanding American middle class of the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. Today, their average age is in the upper forties. They have a tremendous belief in education; over 80 percent of them are college graduates and nearly half hold advanced degrees, but they are far more likely to have attended a public college than an Ivy League one. They also believe in the importance of family; that is, they got married, had kids, and have largely been successful at keeping their families together.

They have worked hard, typically for a long time with a respectable but not spectacular salary. Financial abundance often came suddenly, in a liquidity event triggered by a company’s going public or being acquired, or a bonus afforded a new partner or some other watershed business moment. On average, this liquidity event happened about ten years ago. Most of them are still learning to live with abundance, but they have held on to their middle-class attitudes; in fact, most still describe themselves as middle class at heart.

Conspicuous consumption garners the headlines, but it is as unrepresentative as are images of inherited wealth. Most of the successful live lives and buy products that are subtle and understated, a tendency that accelerated during our recent Great Recession, as phrases such as “logo shame” entered the lexicon and displays of wealth came across as insensitive rather than impressive. When it comes to brands, they look for quality, craftsmanship, and service. The social and emotional qualities of brands, such as making one feel or appear successful, are much less influential in their purchases. Table 3.2 shows the contrast between myths and realities regarding this group; Table 3.3 captures some of the group’s essential beliefs and attitudes.

THE BIGGEST MYTH

ABOUT THE AFFLUENT

Perhaps the most enduring myth about the affluent is that accumulating money is their primary motivation in life, their raison d’être. Instead, they are most often people who pursued a passion. They worked hard. They typically had good timing or a bit of good luck, and often some of both. And their efforts to pursue their passion took off to a degree that almost surprised them. Financial abundance followed, but it was more as a symptom or aftereffect than the primary motivation.

TABLE 3.2

Myths and Realities of Today’s Wealthy

TABLE 3.3

The Journey of the Affluent, in Their Own Words

Middle-Class Upbringings

“I lived on Elm Street USA. . . . [Years later] I went back there, and it was like, ooh, the house wasn’t as big as I thought, and, ooh, those trees just weren’t as large as I thought they were. But, in my mind they were huge, and it was great, and the yard just went forever.”

Risk-Taking Entrepreneurship

“My transition from the corporate work-a-day world to [running a successful business] involved first giving it all up, sacrificing, and living on a vineyard without electricity. Without running water. Without a toilet. In a double-wide mobile. With an 18-month and a 3½-year-old. With no income, no cash flow, no nothing. Nose diving into debt. All to get this thing up and running . . .”

Years of Dedication and Sacrifice

“Somehow over the years, folks have gotten the impression that Wal-Mart was something I dreamed up out of the blue as a middle-aged man, and that it was just this great idea that turned into an overnight success . . . . Like most other overnight successes, it was about 20 years in the making.” —Sam Walton, founder of Wal-Mart

“The first call I got was my brother-in-law looking for a loan. My friends thought I had changed. It’s no wonder I spend much of my time disguising my success.”

Maintaining Integrity and Moral Fiber

“Though I am grateful for the blessings of wealth, it hasn’t changed who I am. My feet are still on the ground. I’m just wearing better shoes.” —Oprah Winfrey

Managing Money Across Generations

“Our kids are great. But I would argue that when your kids have all the advantages anyway, in terms of how they grow up and the opportunities they have for education, including what they learn at home, I would say it’s neither right nor rational to be flooding them with money.” —Warren Buffet

Redefining Retirement

“The ability to bring on top executives for a large-sized business gives me the luxury of essentially not working. I’m kind of halfway between president and chairman. You know, I’ll take the summer off and go to Europe with the kids, and it’s not an unexpected thing, because I do it pretty much every summer. And there’s a team there that knows how to run it, knows what level of things I need to be involved in. I’ve got [a colleague] coming in twice a month to kind of look things over for me, help me out. He’s retired; he doesn’t want to stay home all day, so it’s a good thing for him, it’s a good thing for me.”

Source: Harrison Group and American Express Publishing, Survey of Affluence and Wealth in America, 2010.

In our survey of the financially successful, we asked the participants about these dynamics—about the relationships among money, striving, and success. They responded:

• “To me, money is the by-product [of] professional activity, the passion, the enthusiasm, and the knowledge of your subject. . . . The goal has never been [to make] money. The goal has been [to learn, to have] adventures, have fun, share.”

• “I didn’t care to get to the top. I never tried to get to the top. I tried to do a good job and they put me there in spite of it or because of it.”

• “We worked real hard to build this company—my wife and family and myself. We looked around one day, and my business gave us a lot of things we never dreamed of. But it was the work, and what we were able to do for our customers and the people in this town, that made us happy. I guess I can’t say that I’d be happy if we were poor, but I don’t want anyone to think being able to buy what we want makes us happy. . . . [B]eing able to do what we want makes us happy.”

Certainly, passion characterizes how most of these successful individuals approach their careers, although perhaps it is more precise to say that they have aligned their careers with their passions. Regardless, it was the ensuing career success that generated their income and assets. They are the entrepreneurs, the CEOs and their C-level brethren (CFOs, CPOs, COOs), the lawyers, the accountants, and other providers of professional services. As people rise out of the affluent ranks and into the more rarified air of the truly wealthy, they are mostly business founders and CEOs.

The vast majority remain on the front lines of their businesses, working well beyond meeting their financial needs, quite simply because it was never really about the money. Most of them agree that their career is a “critical element” in their self-esteem, and nearly half agree that their lives revolve around their careers. Three-fourths feel that they work harder than most people they know. And doing business in today’s difficult economic climate spurs additional challenges; fully half say, “My job now requires that I work harder for less reward.” In fact, when we asked for the secrets of their success, “hard work” topped the list, followed closely by “determination,” “intelligence,” and “education.”

THE PASSION FOR FAMILY

AND THE “WE NEED” ECONOMY

Aside from their passion for their work, the other great passion in the lives of the affluent is family. Freud famously called work and love the foundations of modern human life,1 and this certainly seems to be the case among today’s affluent. Eighty-two percent of our surveyed group are married, including 64 percent who are married to their first spouse. Three-fourths describe themselves as “a much more involved parent than my own parents were with me,” and a similar number eat dinner together as a family at least four nights a week. Only 19 percent feel misunderstood by their kids. Indeed, the family spirit runs strong; it even transcends the human species: Ninety-four percent of pet owners in this group consider their pets “part of the family.”

Two of our wealthy research participants explained:

• “The key to success in life? [laughter] A happy family life, having a happy, positive business life, and being able really in your business to provide a service or product for your customers. And then being happy with the service that you provide for them.”

• “[Success in our family life is about] sharing passion. Certainly, that’s a big thing for us. Because we are both so committed to [our business], it would be very separating if only one of us was involved in that.”

The Economic Downturn Strengthens the Family

The strong focus among the affluent on the family has intensified, not weakened, as a result of the economic downturn. When the going got tough, the team pulled together. Nearly 90 percent feel they have “done a good job of making my household more fiscally responsible,” and two-thirds agree that “my significant other and I have learned to work together because of the economy.”

This represents a fundamental shift in how consumers weigh their purchasing priorities. The early and mid-2000s were characterized by an “I want” economy: a consumer-meets-Caesar ethic of “I came, I saw, I bought.” Magazines were glossy enticements to consumption, thick with ads, less focused on encouraging the urge to purchase than on channeling the presumed urge to purchase toward a particular brand. The stock market was rising; home values were strong. Seven in ten affluent individuals described themselves as extremely or very optimistic about the future. Family was important, to be sure, but consumption in the service of individual desires consumed significant emotional and financial resources.

The future seemed bright—that is, until 2006 and the crash of the subprime housing market. In truth, we began to see significant purchasing and general economic anxiety in our surveys throughout 2006. Since there were few general economic threats, other than soaring real estate debt, to justify the magnitude of anxiety we were seeing, we referred to this advancing fear as the start of the “emotional recession.” That is, optimism about the future was dropping. Concerns about the long-term stability of the housing market were creeping in. The pollsters’ “right track/wrong track” measures showed growing numbers of consumers as uneasy with the direction of the country.2 America was battling international terrorism and was engaged in two expensive land wars. There was a growing sense that our society—business, government, and individuals—had simply been living unsustainably beyond its means.

Spending cutbacks accelerated throughout 2007, and the National Bureau of Economic Research (the private, nonprofit group of economists charged with dating recessions) would later peg the official start of the recession at December 2007. But the emotional underpinnings were apparent over eighteen months earlier. In reality, it was 2006 that had seen the transition from an “I want” economy to an “I need” economy. Anxiety was in the air. Discretionary spending was cut to an absolute minimum. Perceived risk was ever-present. The diminishing role of consumption and acquisition was met with a sense of sadness and self-deprivation. It would only get worse.

As 2008 started, our research showed consumers cutting back even further. In September 2008, the government decided that Lehman Brothers was not too big to fail, and the company’s subsequent bankruptcy sent shockwaves through the markets. The fear catapulted into a full-scale financial panic when the October 2008 financial statements were opened. Christmas 2008 was a time of change for families and merchants, as well as an inflection point for the American economy as a whole. Consumers hedged the loss of purchasing power, in part, by shifting their shopping online. At that time, many retail stock-keeping units, or SKUs, particularly those relevant to the holiday shopping experience, could be purchased online at substantial discounts from keystone retail prices. So, trapped between cutting back or moving their purchasing to the lowest cost channel, retailers were caught unprepared, and they offered huge discounts to unload inventory. Still, low prices were met with even lower consumer interest, making the holiday season of 2008 one of the worst in history.3

Retailers were better prepared for the 2009 holiday season, now holding less inventory and ready with value-oriented offerings, but in terms of consumer enthusiasm for spending, 2009 showed little improvement over 2008. By early 2010, optimism among the affluent had jumped significantly, but a majority of them still expected the recession to last longer than a year, and spending continued to be significantly suppressed.

Throughout this economic tumult, affluent families got tighter and stronger. Spouses talked more openly about money, and marriages held together. Parents talked about money with their kids and soothed their fears; they started spending less on their kids, and kids actually appreciated the financial responsibility that kind of restraint reflected. Money continued to be spent, for sure, but increasingly it was on things for the family. The “we need” economy had arrived. For example, while spending on fashion and jewelry continued to drop, spending on family vacations was one of the first categories to see an end to consumer cutbacks.

Certainly there were changes in spending patterns among the affluent. Weekend getaways were up, while multiweek vacations were down, for example. And there were changes in value expectations, too. When we asked affluent families how their personal travel plans were expected to change as a result of the recession, the most common response was that they would stay in the same quality of accommodation, but they would expect a better deal. It remained a challenging environment for travel and lodging providers at all price points, but for their customers it was clear that the desire to bring the family together was deemed a worthwhile reason for spending the money.

Lasting Changes in Spending Patterns

Not only has the passion for family pulled the affluent closer during these challenging times, but our research has shown that it has even reshaped the process by which household decisions get made. Certainly most big decisions are team decisions, but it is most often the female head of household who is the team leader. She is, within the typical American family (affluent and otherwise), effectively the chief executive officer, chief financial officer, chief purchasing officer, and chief operating officer. We’ve called this paradigm shift the “New American Matriarchy,” or more informally, the “mom-ocracy.” Our research has shown that she is more likely than the male head of household to be responsible for most household tasks, ranging from scheduling household appointments and making most purchases, to paying the bills and making investment decisions.

A majority of affluent women agree with the statement, “In the end, my opinion determines the family financial decision.” In fact, the only household task that men are more likely to be responsible for is mowing the lawn. Move over, glass ceiling, the grass ceiling is here. Her shopping style tends to be thoughtful and precise; the result is a growth in affluent shopping patterns that are so savvy and sophisticated that they are reminiscent of how businesses make purchasing decisions. Mom makes decisions through discussion and consensus, not by fiat. Everybody’s opinion is solicited and considered, including the kids’.

MONEY, CULTURE, AND THE NICHE PASSIONS

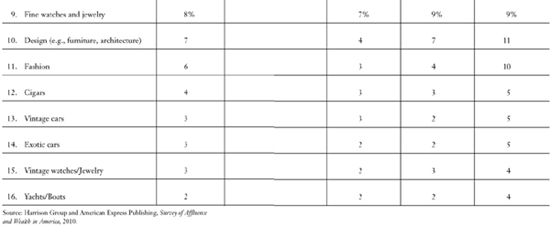

If career and family are the top two passions for the affluent and wealthy, what other factors come into play? The answer is that there is no clear third-place winner. From there, our research shows that the passions of the affluent are highly idiosyncratic. What excites one person inspires yawns from another. Travel comes closest—a passion for half of our respondents. Foodies, wine buffs, and music lovers are overlapping categories of passion, but each accounts for about one-third of the surveyed population on its own. Certainly the affluent like money, as virtually everyone does, and we’ve seen that money is not the primary motivation in their career strivings. Only 29 percent describe themselves as passionate about money, making them about as prevalent among the wealthy as are book collectors, techno geeks, political junkies, shopaholics, health fanatics, and the sincerely religious (see Table 3.4).

TABLE 3.4

What the Affluent Are Passionate About

(% surveyed; top 20 interests shown)

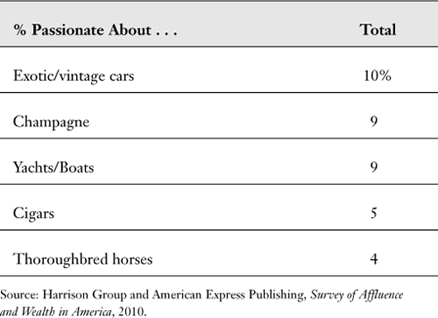

Notable by their absence from Table 3.4 are what one might characterize as “the Robin Leach passions”—the yachts, champagne, exotic cars, cigars, and other accoutrements of opulence so prominently featured on Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, or its more recent progeny, Cribs, or in the music videos that exemplify the aspirations of a new generation. In fact, these interests are found among only 5 to 10 percent of the affluent population (see Table 3.5). Of course, these are not insubstantial numbers in absolute terms; that is, the 10 percent of the affluent who are passionate about exotic cars, for example, constitutes a market of roughly 1 million people. Still, these aren’t the passions of the majority.

TABLE 3.5

Niche Passions of the Affluent

(% of those surveyed)

But even among those who are passionate about a niche category, money often remains a barrier to full-bore consumptive participation, as a connoisseur or as a collector. Consider that 5 percent of the affluent are passionate about cigars, and 4 percent describe themselves as cigar connoisseurs or collectors. Put another way, with few barriers to entry, 80 percent of those with a cigar interest follow through with significant spending. In contrast, less than half of those who are passionate about a niche interest such as exotic cars or yachts actually “convert” to being collectors (see Table 3.6). Still, connoisseurship remains a collection of niches—no single realm captures more than 20 percent of the market.

The same pattern emerges from a study of the philanthropic efforts of the affluent (see Table 3.7). Eighty-six percent agree with the statement, “I am passionate about the causes I give to,” but no single type of charity predominates. In fact, the growing trend is for the affluent to start their own foundations, to ensure that their money and their efforts go precisely to their areas of interest.

THE ARC OF MATURATION AND

THE EVOLUTION OF PASSIONS

Living with abundance is a learning process, a journey for which the affluent’s middle-class backgrounds did not prepare the members of this group. Generations of Rockefellers, Carnegies, and Mellons learned from the collective wisdom of their families about sophisticated spending, investment, and philanthropy. They grew up hearing about the subtleties of buying at the high end in literally hundreds of categories. They experienced the sublime distinctions of quality, materials, and heritage that separate Chanel from Coach, Armani from Aeropostale, Rolex from Timex, Ritz Carlton from Radisson, Tiffany from Zales, first class from coach.

TABLE 3.6

Percentage of Affluent Who Are Collectors/Connoisseurs

(% of those surveyed)

TABLE 3.7

Percentage of Affluent Who Contribute to

Specific Charity Types (annual % for those surveyed)

Today’s wealthy have to figure it out for themselves. Over 80 percent of the affluent describe having money as “a real learning process.” Most of them have been hit up for money by family or friends. Half of them have been, in their words, “ripped off.” They learned the good and the bad, mostly by themselves, mostly on the fly, as one explained:

“My husband and I are the first generation to enjoy the wealth that we have created, so there are lots of surprises along the way—things you don’t expect. And there’s nobody putting their arm around you helping you figure things out. . . . For instance, when we took the company public, nobody said: ‘Here are five things that you need to really think about.’ There were a lot of things that I was absolutely blindsided by. There is an incredible learning curve.”

Those living with affluence for five years or less—a segment we call “Apprentices”—are characterized by lingering feelings of unreality and a pervasive sense of caution. A majority worry about running out of money. Memories of leaner times are fresh in their minds. Many have had sudden changes of fortune for the better, but they remain anxious that their situations could reverse themselves just as quickly. They have seen their social standing change, again, for better and for worse. They find themselves in exciting but unfamiliar new social circles, while feeling that many old relationships are strained. They fear money will change them and erode the work ethic of their children. They shop cautiously, avoid the highest-end products, and are wary of status symbols. In short, Apprentices are reluctant to embrace new passions, for fear of losing touch with their middle-class sense of self, and they are cautious in indulging their current passions.

Over time, Apprentices mature into “Journeymen.” Time—and in many cases, multiple liquidity events—have begun to assuage their fears. As they reach a comfort zone and are content with acquisition and consumption, they begin to dabble in luxury products in categories to which they have always been drawn. They experiment in indulging their passions. They buy their first seriously expensive toys. And upon seeing the expensive toys and objets d’art of their newly made wealthy friends, they characteristically ask, “Where did you get that?” Existing passions evolve, broaden, and deepen. They grow over time, with experience, with connections to those who share similar passions. And with greater exposure, any modest interest may evolve into a true passion, particularly when cost barriers are eliminated by growing wealth. Consider that Apprentices, on average, have three passions, but during the Journeymen phase, the affluent typically acquire at least one or more new passions.

After fifteen years of living with abundance, the wealthy evolve into “Masters.” Typically their wealth has snowballed. Many have joined the $1 million/$10 million club: $1 million in income and $10 million in assets. They have become comfortable with wealth and the lifestyle it affords. They have, or are working toward, a thought-out and systematic approach to the “big picture” issues of wealth: business succession, estate management, and charity. They maintain many of their middle-class attitudes, particularly in the emphasis on quality and value, but they bring a worldly sophistication and appreciation for subtlety that has been honed for years. They spend more. On everything. Whether it’s homes or fashion or technology, their reluctance to pull the trigger on spending is gone. Masters indulge their passions without hesitation, and they enter the small world where the movers and shakers in their areas of interest all seem to know one another.

Some passions are the “you-have-them-or-you-don’t” variety, consistent in their prevalence across the arc of maturation: family, music, wine, food, books, shopping, health, religiosity, science, charity, and fashion. In these areas, Apprentices and Masters are equally likely to express an enthusiasm. Other areas of passion show distinct growth; with more time and money, and with greater experience in the joys of a category, their interests evolve into passions. Examples of these include travel, art, theater, design, cars, and politics. When we switch from looking at the “merely” passionate to those who describe themselves as connoisseurs and collectors, the growth across the arc of maturation is evident in virtually every area—microbrews and spirits are the only exceptions (see Table 3.8).

TABLE 3.8

Affluent Who Are Collectors/Connoisseurs (% of surveyed)

THE ARC OF MATURATION AND

SELLING FINANCIAL SERVICES

The arc of maturation is, ultimately, a process of learning about the power of money. So perhaps it comes as little surprise that the members of these three segments—Apprentices, Journeymen, and Masters—approach investing and financial services very differently. Apprentices, as we have seen, are risk averse. They fear running out of money, are accumulation-focused, and shy away from complex financial instruments. Journeymen are financially aggressive, and they introduce significant diversity into their portfolios. Masters like to think of themselves as very conservative, focused on long-term (often multigenerational) planning for their wealth, but they pursue it in a way that would be objectively characterized as aggressive (e.g., extending into hedge funds, commercial real estate, private equity funds, even thoroughbred horses). Figure 3.1 summarizes the financial perspectives of the three segments.

The key to success for those selling financial services becomes identifying where a prospect is in the arc of maturation, and tailoring the sales approach and portfolio recommendations accordingly (recall our discussion of “adaptive selling behavior” in Chapter 2). Obviously, coming straight out and asking, “So how long have you been rich?” will raise a red flag, so a more subtle approach to gathering information is required, usually by listening intently to any information offered proactively or easily elicited.

FIGURE 3.1

Financial Concerns Across the Arc of Maturation

At the risk of overgeneralization, we give you some indications of status. You are talking with Apprentices if:

• They agonize over risk.

• They fear making mistakes.

• They ask you what you do.

You know you are talking to Journeymen when:

• They talk about what other people think of them.

• They ask you where you got something.

• They want to be given inside opportunities.

And you know you are talking to Masters when:

• They have an informed view of risk.

• They have reserve cash for passions such as collecting and giving.

• They ask you about your family.

Now that you have identified a prospect and his or her likely needs, the next step is to tailor your approach. Table 3.9 lists some do’s and don’ts for each segment.

PASSION AS THE MISSING

INGREDIENT IN SALES

We’ve shown passion as the defining element in the lives of both top salespeople and the wealthy prospects to whom they sell. Here’s the disconnect: Most wealthy people believe salespeople lack passion. In our Affluent Attitudes Toward Salespeople survey, we asked people to estimate what percentage of salespeople in a given category they have experienced as truly passionate about their jobs. Purveyors of art garnered the highest ratings: two-thirds of them are believed to be passionate about their work. The best that the other ten categories can muster is a figure hovering near the Mendoza line of 50 percent, as shown in Table 3.10. In high-end financial services, jewelry, real estate, and luxury retail stores, affluent consumers believe their odds are only 50-50 of working with someone who truly cares. Clothing boutiques and upscale department stores fared even worse, and only one in four expects it from used-car salespeople.

TABLE 3.9

Do’s and Don’ts of Selling to Wealthy Segments

SUMMING UP

The previous chapter explored the role of passion in sales success; as a result, we suggested renewing and intensifying your efforts to discover and deepen your passions. This chapter painted a detailed portrait of today’s affluent, rich with implications for sales success. To sell to the affluent, you address middle-class sensibilities and speak to today’s understated preferences. You also sell to the family as a team, with the female head of household as leader. You express your integrity and maintain and communicate your quality. Table 3.11 pairs these sales qualities with the values of the affluent and wealthy.

TABLE 3.10

Fields in Which the Affluent Perceive Salespeople

as Passionate (% surveyed)

TABLE 3.11

Summary of Key Take-Aways

THE NEXT STEP

The biggest implication of this information is that successful salespeople need to understand the passions that inspire their prospects. Take a “passion census” of your customers. Do you really understand their businesses? Their families? Their hobbies and interests? In sales training seminars, we often ask salespeople to write a “personal ad” describing their target in detail. Then we ask them to list the in-person or online communities (“watering holes”) that might attract their ideal prospect. For example, in Chapter 2 we mentioned that we worked with one of the top Hummer sales-people in the country, and he identified a passion he shared with most of his prospects—a love of the outdoors. He then joined several groups focusing on hunting, fishing, conservation, and other topics of interest among those who shared that passion. Lo and behold, he found himself surrounded by like-minded individuals who happened to be ideal prospects for the Hummers. And as GM wound down the Hummer brand, he was able to transition into selling brands that still spoke to the passion he shared with his customer base.