CHAPTER 2

THE NATURE OF SERVICE AND SERVICE CONSUMPTION, AND ITS CUSTOMER MANAGEMENT IMPLICATIONS

“Goods and services merge – but on the conditions of service.”

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter the nature and characteristics of service are discussed. The consequences of the process of how service is consumed and used as well as the difference between process consumption and outcome consumption are also covered. Finally, the implications of process consumption, which characterizes service and the content and scope of marketing, are described. After having read this chapter the reader should understand the nature of service and of service consumption as compared to the consumption or use of physical products, as well as the scope and content of marketing in service contexts compared to goods marketing. The reader should also understand what main sources of competitive advantage exist for service businesses.

WHAT IS A SERVICE? AN ATTEMPT TO DEFINE THE PHENOMENON

A service is a complicated phenomenon. The word has many meanings, ranging from personal service to service as a product or offering. The term can be even broader in scope. A machine, or almost any physical product, can be turned into service to a customer if the seller makes efforts to tailor the solution to meet the most detailed demands of that customer. By adopting a service logic a firm can turn any resource into service for customers. A machine is still a physical good, of course, but the way of treating the customer with an appropriately designed machine is service. Sir John Harvey-Jones, former chairman of ICI, said almost three decades ago, referring to some successful firms in the chemical industry, that they had developed an ability to provide a chemical service to customers, rather than selling chemical products.1 The Kone Corporation, one of the world’s leading elevator and escalator manufacturers, headquartered in Finland, has successfully transformed its manufacturing and service businesses into one business, ‘dedicated to people flow’. A growing number of manufacturing firms have changed their focus and claimed at least that they are becoming service businesses.

Moreover, as we have discussed previously, there is a variety of administratively managed activities, such as invoicing and handling claims, which in reality are service to the customer. Because of the passive way in which they are handled, they remain ‘hidden services’ for customers. In fact, they are usually taken care of in such a way that they are perceived not as service but rather as nuisances. Obviously, this offers several opportunities to create a competitive advantage for organizations that can innovatively develop and make use of such ‘hidden services’ and integrate them with the core of the offering, such as a physical product or a service concept, into a total service offering.

A range of definitions of service have been suggested. Traditionally these definitions focus upon the service activity, and mainly include only those services rendered by so-called service firms.2 As a criticism of the variety of definitions suggested, Gummesson, referring to an unidentified source, put forward the following definition: ‘A service is something which can be bought and sold but which you cannot drop on your feet.’3

Although this definition in a way criticizes attempts to find a definition that could be agreed upon by everyone, it points out one of the basic characteristics of services; that is, that they can be exchanged although they often are not tangible as physical products.

Today, service carries at least two distinctly different meanings:

Service as a perspective on business and marketing (service logic).

Service as an activity.

Service as a perspective was discussed in Chapter 1. Here we discuss the latter meaning of service. One should, however, keep in mind that these two ways of understanding service are intertwined. When adopting a service logic (the perspective), all kinds of resources – goods as well as service activities and other types of resources – are presented to customers in a way resembling service activities. In principle, there is no difference between the beef in a restaurant’s service activity and an elevator in an offering aiming at ‘supporting people flow’ (the Kone Corporation). They are both resources needed to provide service to customers. Hence, the discussion of service as activities is relevant for understanding service as a perspective. Since the 1980s much less discussion of how to define service as an activity has taken place, and no ultimate definition has been agreed upon. Nevertheless, in 1990 the following definition4 was proposed (here slightly modified):

A service is a process consisting of a series of more or less intangible activities that normally, but not necessarily always, take place in interactions between the customer and service employees and/or physical resources or goods and/or systems of the service provider, which are provided as solutions to customer problems.

Most often a service does involve interactions of some sort with the service provider. However, there are situations where the customer as an individual does not interact with the service firm. For example, when a plumber using the main keys of an apartment complex goes into an apartment to fix a leak when the tenant is out, there are no immediate interactions between the plumber, his physical resources or systems of operating and the customer. On the other hand, many situations where interactions do not seem to be present nevertheless do involve interactions. For instance, when a car problem is taken care of at a garage, the customer is not present and interacting with anybody or anything. However, when the car is taken in by the garage and later delivered to the customer, interactions occur. These interactions are part of the service. Moreover, they may be extremely critical to the customer experience. The customer probably cannot properly evaluate the job done in the garage but can, however, evaluate it based on the interactions that occur at both ends of the service process. Sometimes, as in the case of Internet banking or phone calls, the customer interacts with an infrastructure and systems provided by the bank or telecom operator. Although customers tend to notice them only when they fail, these interactions are equally important to the success of this service as interactions with employees. Consequently, in service, interactions are usually present and of substantial importance, although the parties involved are not always aware of this. Furthermore, service is not a thing, it is a process or activities, and these activities are more or less intangible in nature.

Since 1990 the importance of information technology to service has increased dramatically. Systems indicated in the definition of service are increasingly based on IT and Internet-related solutions and mobile technologies.

The most important contribution to marketing theory and practice by service research, especially emphasized by the Nordic School, is the notion of interaction instead of exchange as a focal phenomenon.5 Without including interactions between the service provider and the customer during the consumption process as an integrated part of marketing, successful marketing cannot be implemented and realistic marketing models cannot be developed. Although at some point exchanges have taken place, it is successful management of interactions that makes exchanges possible. A first exchange may occur, but without successful interactions continuous exchanges will not take place. Moreover, as service is a process rather than an object of transaction it is impossible to assess at which point in time an exchange takes place. Money can be transferred to the service provider either before the service process or after the process, or continuously on a regular basis over time.

SOME COMMON CHARACTERISTICS OF SERVICE

Service, both as a perspective and an activity, has specific characteristics. A whole range of characteristics has been suggested and discussed in the literature. Traditionally service is compared with physical goods.6 This is, however, not a very fruitful way of developing service models. Service and the nature of service management and marketing should be understood in their own right.

The specific models and concepts of service management and marketing follow from the fact that the customer is present to a certain degree in the service process, where service is produced and provided to him, and that the customer also participates in the process and perceives how the process functions at the same time as the process develops. This is the case also when customers are serviced seemingly on their own, such as paying invoices using an Internet banking option or a vending machine to get a cup of coffee. The customer is involved in a service process, interacting with systems and infrastructures provided by the service firm and, as in the case of making a phone call, also with another customer. In these interactions as a co-producer the customer influences the progress of the service process and the outcome of it just as much as when having dinner in a restaurant. One of the reasons that understanding service management is of interest to manufacturers of goods is that customers are now more involved in various processes of the manufacturer such as the design of goods, modular production, delivery, maintenance, helpdesk functions, information sharing and a host of other processes which, in today’s competitive environment, have become important for the creation of a competitive advantage. When manufacturers take a lifecycle approach to managing their customer relationships, i.e. set out to take care of their customers’ varying needs of support over time instead of only selling products or delivering services to them at a discrete point in time with a transaction approach, taking care of their customers becomes a service management issue.

For service in general, three basic and more or less generic characteristics can be identified:

Service is a process consisting of a series of activities.

Service is at least to some extent produced and consumed simultaneously.

The customer participates as a co-producer in the service production process at least to some extent.

By far the most important characteristic is the process nature of service and service activities. Service is a process consisting of a series of activities where a number of different types of resources – people as well as goods and other physical resources, information, systems and infrastructures – are used, often in direct interactions with the customer, so that a solution is found and thus value emerges for the customer. Because the customer participates in it, the process, especially the part in which the customer is participating, becomes part of the solution. Most other characteristics follow from the process characteristic. In later sections we shall go into the implications for management and marketing of this process nature of service.

Because service is not a thing but a process consisting of a series of activities – produced and consumed simultaneously (this is also called the ‘inseparability’ characteristic) – it is difficult to manage quality control and to do marketing in the traditional sense, since there is no pre-produced quality to control before the service is sold and consumed. Of course, situations vary, depending on what kind of service is being considered. A hairstylist’s service is obviously almost totally produced when the customer is present and receives it. When delivering goods, only part of the service (production) process is experienced and, thus, simultaneously consumed by the customer. Most of the process is invisible for the customer. However, in both cases, one should realize that it is the visible part of the service process that matters in the customer’s mind. As far as the rest is concerned, he can only experience the outcome; but the visible activities are experienced and evaluated in every detail. Quality control and marketing must therefore take place at the time and place of simultaneous service production and consumption. If the firm relies on traditional quality control and marketing approaches, the part of the service process where the customer is involved may go uncontrolled and include negative quality and marketing experiences.

The third basic characteristic of service points out that the customer is not only a receiver of the service; the customer participates in the service process as a production resource as well. Hence, the customer co-produces the service and when there are interactions with the firm’s resources he may also co-create value with the firm.

In addition to the three basic characteristics, other important aspects of service can be distinguished. For example, it is not possible to keep service in stock in the same way goods are. If an airplane leaves the airport half-full, the empty seats cannot be sold the next day; they are lost. Instead, capacity planning becomes a critical issue. Even though service cannot be kept in stock, one can try to keep customers in stock. For example, if a restaurant is full, it is always possible to try to keep a customer waiting in the bar until there is a free table.

In much of the service literature intangibility is said to be the most important characteristic of a service. However, physical goods are not always tangible either in the minds of customers. A kilo of tomatoes or a car may be perceived in a subjective and intangible way. Hence, the intangibility characteristic does not distinguish service from physical goods as clearly as is usually stated in the literature. And intangibility is certainly not the most important characteristic. However, service is characterized by varying degrees of intangibility. Normally service cannot be tried out before it is purchased. One cannot make a trial trip on a new airline or try out an inclusive tour before buying it. Furthermore, being on a holiday at a resort is largely an experience or a feeling that as such cannot be captured in a physical way.

Service is normally perceived in a subjective manner. When service is described by customers, words such as ‘experience’, ‘trust’, ‘feeling’ and ‘security’ are used. These are highly abstract ways of formulating what service is. The reason for this, of course, lies in the intangible nature of service. Often service include highly tangible elements as well: for example, the bed and amenities in a holiday resort, the food in a restaurant, the documents used by a forwarding company, the spare parts used by a repair shop. The essence of service, however, is the intangibility of the phenomenon itself. Because of the high degree of intangibility, it is frequently difficult for the customer to evaluate a service. How do you give a distinct value to ‘trust’, or to a ‘feeling’, for example? Therefore, it is often suggested in the literature that one should make service more tangible for the customer by using concrete, physical evidence, such as plastic cards (in banking) and various kinds of atmosphere-related artefacts (in a restaurant). However, many physical goods, such as a sports car or luxury cellular phone, are equally intangible and perceived in a subjective way by customers.

Furthermore, many definitions imply that service does not result in ownership of anything.7 Normally this is true. When we use an airline’s service, we are entitled, for example, to be transported from one place to another, but when we arrive at our destination, there is nothing left but the boarding card. When we withdraw money from our current account we may feel that the bank’s service resulted in our ownership of the withdrawn money. After the service process, we undoubtedly have the sum of money in our hands and we own it. However, the bank’s service did not create this ownership. We, of course, owned the money all the time. On the other hand, retailing is service, and after using service provided by, say, a grocery store, the customer undoubtedly owns the groceries.

Finally, because of the impact of personnel and customers or both, on the service production and delivery process, it is often difficult to maintain consistency in the process. Service to one customer is not exactly the same as the ‘same’ service to the next customer. If nothing else, the social relationship in the two situations is different and the customer may act in different ways. The service a customer receives by using an ATM may differ from the ‘same’ service received by the next customer because, for instance, the second person has a problem understanding the instructions on the screen. The inconsistency in service processes creates one of the major problems in service management; that is, how to maintain an evenly perceived quality of the service rendered to customers.

CLASSIFICATION SCHEMES FOR SERVICE

In many publications from the early days of service marketing research, service was classified in a number of different ways.8 Here we are only going to discuss two classifications:

High-touch/high-tech service.

Discretely/continuously rendered service.

First, service can be divided into high-touch or high-tech. High-touch service is mostly dependent on people in the service process, whereas high-tech service is predominantly based on the use of automated systems, information technology and other types of physical resources. This is of course an important distinction to make. However, one should always remember that high-touch also includes physical resources and technology-based systems that have to be managed and integrated into the service process in a customer-oriented fashion. While high-tech service, such as telecommunications or Internet shopping, by and large is technology-based, in critical moments, such as complaints situations or technology failures, or in built-in contacts with service employees representing, for example, helpdesk operations, the high-touch characteristic of the technology-based service takes over. In fact, one can say that high-tech service is often even more dependent on the service orientation and customer-consciousness of its personnel than high-touch service, because human interactions occur so seldom and when they occur they do so in critical situations. If these high-touch interactions of the high-tech service process fail, there are fewer opportunities to recover the mistake than in high-touch processes. In these cases high-touch contacts are true moments of truth for a firm, making it possible to secure a favourable quality perception in the end.9

Second, based on the nature of the relationship with customers, service can be divided into continuously rendered service and discrete transactions. Service such as industrial cleaning, security service, goods deliveries, banking, etc. involve a continuous flow of interactions between the customer and the service provider. This creates ample opportunity for the development of valued relationships with customers. For providers of discretely used service, such as hair stylists, many types of firms in the hospitality industry, providers of ad hoc repair service to equipment and so on, it is often more difficult to create a relationship that customers appreciate and value. However, as we know from many hair stylists, hotels and restaurants and other providers of discretely used service, this is possible and is considered a profitable strategy. Firms that offer service which are used on a continuous basis cannot afford to lose customers, because the cost of finding new customers is often high. On the other hand, firms offering service that is used in a discrete fashion may also develop a profitable business based on transaction-oriented strategies, although a relationship orientation is probably to be recommended in most cases.

The models and concepts of service management discussed in this book are intended to be useful for all types of service firms and manufacturers for which service competition is important, and therefore useful for high-touch as well as for high-tech service, and for continuously rendered service as well as for discretely used service. However, service is always in some respect unique, and when developing strategies and implementing them this should be taken into consideration.

THE CONSUMPTION OF SERVICE: PROCESS AND OUTCOME CONSUMPTION

The focus on the interactions between the service firm and its customers in service research made consumption of service an important marketing issue. In traditional marketing models consumption is not a central issue. Marketing is geared towards sales and making customers buy. In goods-oriented models consumption is more or less a black box. In service marketing research the black box of consumption was opened up and explored. From a marketing point of view, consuming service is seamlessly integrated with buying service.10 Interactive marketing (which will be explored further in Chapter 9) is the part of total marketing that is geared towards managing interactions with the customer during the consumption process in a value-supporting way, in order to increase the likelihood that the customers decide to stay with the firm.

In service research there has been no attempt to define the scope of the consumption process. In reality it is difficult to determine when consumption and customers’ value creation starts and ends. For example, depending on how broadly consumption is defined, the consumption of an inclusive tour to a tourist destination may begin already when the customer starts thinking about taking the trip, or when the first interaction with an advertisement by the tour operator is seen. There may be a mental pre-consumption even before interactions with the tour operator’s processes commence. Also, it may be difficult to determine when consumption ends. A similar mental post-consumption may take place. Using the inclusive tour example, one could say that consumption does not necessarily end when the customer returns home, but when memories of the trip are not brought up in discussions or entering the person’s mind anymore.11

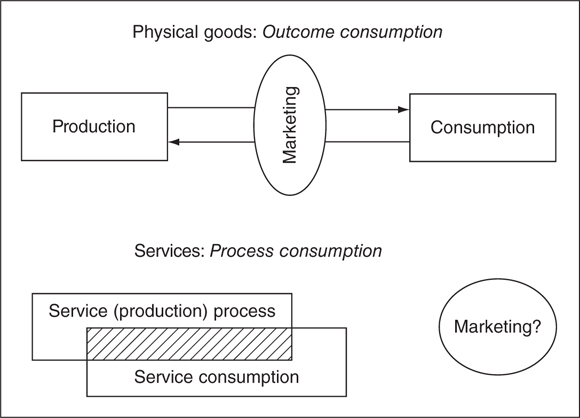

In order to understand service management and the marketing of service it is critical that one realizes that the consumption of service is process consumption rather than outcome consumption. In the case of physical goods, customers consume the outcome of the production process. In contrast, when consuming service customers perceive the process of producing service to a greater or smaller degree, but always to a critical extent, as well as take part in the process as co-producers. Thus, the consumption of the service process is a critical part of the service experience.

As service quality research demonstrates (see Chapters 4 and 5), experience of the process is important for the perception of the total quality of a service, even though a satisfactory outcome is necessary and a prerequisite for good quality. Often the service firm cannot differentiate its outcomes from those of its competitors. Withdrawing a given sum of money from a current account leads to the same result; the customer gets the requested amount, regardless of which bank is rendering the service. Flying from one place to another takes the passenger to the destination, regardless of which airline he patronizes. In some situations customers take the quality of an outcome for granted, and in many situations it is difficult for a customer to evaluate the quality of the outcome of the service process. For example, it is difficult to evaluate whether an Internet website provided by one firm is better than that which another firm could have offered. However, in every situation customers take part in the service processes and interact with the employees, physical resources, technologies and system of the service provider to some extent. The process easily distinguishes one service from another. Because of this inseparability of the service process and the consumption of a service, the process can be characterized as an open process. Hence, regardless of how the customer perceives the outcome of a service process, service consumption is basically process consumption.

In Figure 2.1 the nature of the consumption of physical goods (outcome consumption) and the consumption of service (process consumption) is illustrated. The relationships between production, consumption and marketing are shown in the figure. In the case of outcome consumption of physical goods, which is illustrated in the upper part of the figure, production and consumption are processes that are separated from each other in time and space. The traditional role of marketing, which is defined by the requirements of consumer goods, follows from this situation. A bridge between production and consumption that closes the gap between these two processes is needed. This bridge has, since the early twentieth century, been labelled marketing.

In the lower part of the figure, process consumption of service is illustrated. Production and consumption are simultaneous processes with interactions between the consumer and the service provider’s production resources – people, physical resources, operational systems and infrastructures, information technology, etc. The obvious conclusion that can be drawn from this is that there is no gap between production and consumption that needs to be closed by a separate activity or function. There is no room for marketing’s traditional bridge-building role in this situation. This can be considered to be the essence of service marketing. Marketing has to be included in the system in a different way than in traditional models. The heart of marketing service is how the service (production) process and service consumption process match each other, so that consumers perceive good service quality and value-creation support, and are willing to continue the relationship with the service provider.12 Of course, some activities of a bridge-building nature remain. For example, market research, as well as efforts, such as pricing, advertising and other kinds of marketing communication, to create an interest among potential customers in the service provider and its service offerings and to create trial purchases, is still required. However, the major part of marketing, managing the firm’s customer relationships and other market relationships, becomes an integral part of the simultaneous service production and service consumption processes.

FIGURE 2.1

The nature of consumption of physical goods and services and the role of marketing.

Thus service consumption and production have interfaces that are always critical to customers’ perception of the service and consequently to their long-term purchasing behaviour. For example, in the bank and airline examples used earlier, the location and security of an ATM or the interaction process in a bank, as well as the check-in, in-flight and luggage claim processes in an airline experience, have a decisive effect on customers’ perception of the service and its quality. Hence, for the long-term success of a service firm the customer orientation of the service processes is crucial. If the process fails from the customer’s point of view, no traditional marketing efforts, and frequently not even a good outcome of the service process, will make them stay with a company in the long run, if they can find an alternative.

It is interesting to observe that in the production of a variety of physical goods, everything from cars and computers to jeans and dolls, customers can be drawn into the planning of goods and the manufacturing processes of the factory, through the use of modern information technology and the Internet, and modern design and modular production techniques. This enables mass customization and interactions between the manufacturer and marketer on the one hand and the customer on the other.13 Levi Strauss makes jeans to order, and Mattel offers customized ‘friends of Barbie’ dolls. One can buy a customer-ordered BMW, and even made-to-order vitamin pills.14 In manufacturing in general this is the case both for consumer markets and business-to-business markets. The physical goods become more and more service-like, and service marketing knowledge and a service management framework are required to successfully manage the business.

Thus it seems inevitable that understanding service processes is becoming an imperative for all types of business, not only for what used to be called service firms. One central reason for management to understand the logic of service management is the fact that the main sources of competitive advantage are different for a service business as compared to a traditional product business.

SOURCES OF COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE IN SERVICE

The main sources of competitive advantage are different in service compared to a product business. For a product business there are of course also other sources of competitive advantage, but the most basic and generic one is standardization and the possibility to produce an item on a large scale with a guaranteed quality. If a product with standardized and to some extent unique features can be developed, it can be reproduced as many times as the available production capacity allows. The drawback is of course rigidity, and any customer who prefers something even slightly different will not buy.

The sources of competitive advantage are different for service businesses mainly because of the process nature of service. Service as a business perspective and also as an activity are ongoing processes which are inherently relational. Relational processes include both social and physical interactions, which are difficult to standardize. Attempts to do that normally leads to a rigid process, which neither the customers nor the firm’s employees feel comfortable with. Employees become frustrated and in the end demotivated to provide good service. Customers see the quality of the service deteriorate, become frustrated and are demotivated to continue buying from the service provider. Unsatisfied customers defect, and business is lost. Lost customers must be replaced by new ones, which increases the firm’s customer acquisition costs. Price pressure may also develop.

Further, service processes have to be systematized in some way, so that unnecessarily complicated and bureaucratic parts can be avoided. However, systematizing is not the same as standardizing. For example, an elevator repair process can be systematized, for example to avoid overlapping activities and delays caused by the wrong sequence of activities, without standardizing the process. Unfortunately, firms often mistake systematizing processes for creating standardized processes.

Service processes can, and should, be systematized, but without destroying the two key sources of competitive advantage of service businesses. These are:

Flexibility when designing service processes.

Adaptability when situations which differ from the normal procedure occur.

Flexibility means that a service process is designed such that it allows for deviations from a normal, or standard, procedure. Flexibility must be built into the service process However, it must be planned, so that limits of allowed deviations are known. Otherwise, employees do not know how far from the standard they are allowed to go. The limit of flexibility is a strategic decision. Refunding customers who want to return something they have bought ‘no questions asked’ is one extreme flexibility limit. On the other hand one can go even further. In the management literature there is a supposedly true anecdote about the Nordstroms stores in the US. This is a top end department store, and when a person returned four new tyres with the wrong dimensions for his car, he was refunded. However, Nordstroms do not sell tyres. Most flexibility limits are of course less extreme. For example, in a restaurant with set menus the waiters can suggest or allow some combinations between menus and à la carte lists. An airline employee knows how to compensate passengers for flight delays or lost luggage, what can be offered automatically, and when a decision by a supervisor is required.

To make sure that customers will get good quality, flexibility must be a forethought, not an afterthought. If it is an afterthought, inconsistent behaviour will follow and customers will be lost. Lack of in-built flexibility leads to rigidity, and one of the central sources of competitive advantage is lost.

Adaptability relates to ad hoc situations that occur in a service process, and is therefore required for successful implementation of flexible processes. Flexibility means that a service process is designed in a certain way. Adaptability means that employees and systems can observe the need for out-of-the-normal behaviour in customer contacts. This requires that customer contact employees have the skills and knowledge to register a need for deviations from the normal procedure and to perform their tasks accordingly in a flexible manner, and are motivated to do so. Systems in the service process must be designed to support adaptability and not to make it impossible. For example, if a waiter observes that a restaurant guest is uncomfortable with the items on the menu, he could ask whether the guest has some special wishes, and then try to offer something that meets the guest’s requirements.

If service processes are standardized, flexibility and adaptability are lost, and the offering reverts to a standardized product. As a consequence, the service firm becomes a product business. On the other hand, if a goods manufacturer adds flexibility to its ways of taking care of its customers, for example in deliveries or maintenance or in hidden services such as invoicing and complaints handling, it moves away from being a product business towards becoming a service business and makes use of sources of competitive advantage in service. (Chapter 16 discusses at length how a manufacturing firm can transform into a service business.)

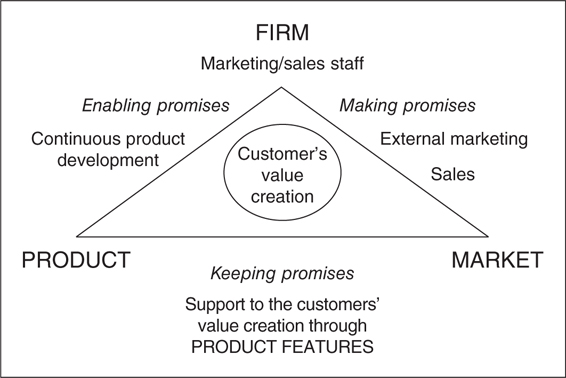

CUSTOMER MANAGEMENT IN A PHYSICAL GOODS CONTEXT: THE TRADITIONAL GOODS MARKETING TRIANGLE

In this and the following section we shall explore how the role of marketing differs between a physical goods and a service context. As a means of illustration we use a marketing triangle. This way of representing the field of marketing is adapted from Philip Kotler,15 who introduced it, to illustrate the holistic concept of marketing suggested by the Nordic School approach to service marketing and management. This triangle’s sides represent making promises, keeping promises and enabling promises.

FIGURE 2.2

The product marketing triangle.

Source: Adapted from Grönroos, C., Relationship marketing logic. Asia-Australia Marketing Journal, 4(1); 1996: p. 9. Reproduced by the permission of the Australasian and New Zealand Marketing Academy.

A physical product, in the traditional sense, is the result of how various resources, such as people, technologies, raw materials, knowledge and information, have been managed in a factory to incorporate a number of features that customers in target markets are looking for. The production process can be characterized as a closed process, where the customer takes no direct part. Thus a product evolves as a pre-produced package of resources and features ready to be exchanged. The task of marketing (including sales) is to find out what product features the customers are interested in and to make promises about such features to a segment of potential customers through external marketing activities such as sales and advertising campaigns, and to take the product to locations where customers are willing to purchase it. If the product includes features that customers want, it will fulfil the promises that have been made to them. This marketing situation is illustrated in the product marketing triangle in Figure 2.2. Customers’ willingness to buy a product and satisfaction with the product are due to how well it supports their value creation, which is indicated by the circle in the centre of the triangle.

In the figure the three key parts of marketing in a goods context are shown. These are the firm, represented by a marketing and/or sales department, the market, and the product. Normally, marketing (including sales) is the responsibility of a department (or departments) of specialists or full-time marketers (and salespeople). Customers are viewed in terms of markets of anonymous individuals. The market offering is a pre-produced physical product. Along the sides of the triangle three key functions of marketing are displayed, to make promises, to keep promises and to enable promises. Promises are normally made through external mass marketing, and in business-to-business marketing, as well as through sales. Promises are kept through a number of product features and enabled through the process of continuous product development based on market research performed by full-time marketers and the technological capabilities of the firm. Marketing is very much directed towards making promises through external marketing campaigns. The value customers are looking for is guaranteed by appropriate product features, and the existence of a product with the appropriate features will make sure that promises made are also kept.

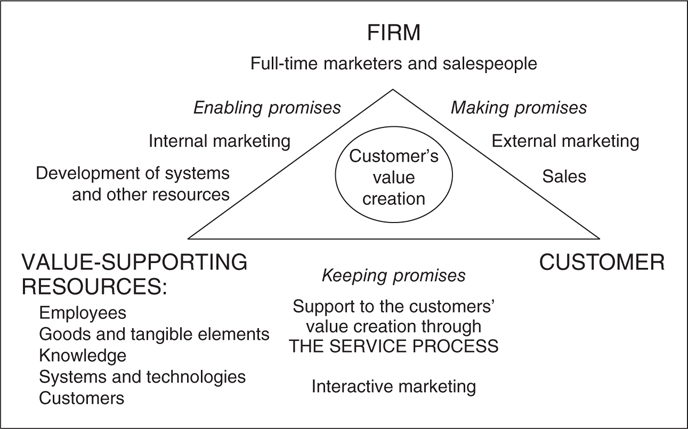

CUSTOMER MANAGEMENT IN A SERVICE CONTEXT: THE SERVICE MARKETING TRIANGLE

For a service business, the scope and content of marketing become more complicated. The notion of a pre-produced product with features that customers are looking for is too limited to be useful here. Also, in the context of business-to-business marketing, the traditional product construct is too restrictive, because a customer relationship often includes many more elements than physical goods, normally various types of service processes, including hidden services.

In many cases what the customer wants and expects is not known in detail at the beginning of the service (production) process or, consequently, what resources are needed, to what extent and in what configuration they should be used is partly unclear. For example, the service requirements of a machine that has been delivered to a customer may vary; the need to provide training for the customer’s personnel and the need to handle claims may vary; a bank customer may only realize what his needs actually are during interactions with a teller or a loan officer. Thus, the firm has to adjust its resources and its ways of using its resources accordingly.

In Figure 2.3, the service marketing triangle,16 marketing in a service context is illustrated. As can be seen, compared to the goods marketing triangle in Figure 2.2 most elements are different. Customers’ willingness to buy service and satisfaction with it are due to how well the service supports their value creation, which is indicated by the circle in the centre of the triangle.

FIGURE 2.3

The service marketing triangle.

Source: Adapted from Grönroos, C., Relationship marketing logic. Asia-Australia Marketing Journal, 4(1); 1996: p. 10. Reproduced by the permission of the Australasian and New Zealand Marketing Academy.

The most important change from the goods marketing situation is the fact that the pre-produced product is missing.17 In process consumption, no pre-produced bundle of features that constitutes a product can be present. Only service concepts and preparations for a service process can be made beforehand and partly prepared service can exist. In many service contexts, such as fast-food restaurants or car rental service, physical product elements with specific features are also present as integral parts of the service process. These product elements are sometimes, as in the case of car rental, pre-produced, and sometimes (as in the case of the hamburger in a fast-food operation) partly pre-produced, partly made to order. However, such physical products have no meaning as such, unless they fit the service process. They become one type of resource among many other types that have to be integrated into a functioning service process. A bundle of different types of resources creates value for customers when these resources are used in their presence and in interactions with them. Even if service firms try to create products out of the resources available, they cannot come up with more than a standardized plan to guide the ways of using existing resources in the simultaneous service production and service consumption processes. Customer-perceived value follows from a successful and customer-oriented management of resources relative to customer sacrifice, not from a pre-produced bundle of features.

The firm may still have a centralized marketing and sales staff, the full-time marketers, but they do not represent all the marketers and salespeople of the firm. In most cases the service firm has direct contact with its customers, and information about each and every customer can be obtained on an individual basis. This is beneficial because, in many cases, customers (business-to-business customers and individual consumers and households alike) like to be treated individually.

In Figure 2.3, the pre-produced product is replaced by an offering consisting of a set of value-supporting resources functioning together with the customer in a service process. These resources of a firm are divided into five groups: personnel, technology, goods, knowledge, and the customer. Many of the people representing the firm influence the customers’ perception of quality and value creation in various service processes, such as deliveries, restaurant service, customer training, claims handling, repair and maintenance, etc. Their way of handling their tasks influences the customers’ perception of quality and willingness to do business with them and the organization they represent in the future as well. Thus, their way of serving customers has a decisive marketing impact. Gummesson has called these customer contact service employees part-time marketers.18 In many service firms they outnumber the full-time marketers many times. In addition, they have customer contacts during the crucial moments of truth when the service is produced for the customer, often together with the customer, something that full-time marketers seldom have.

In addition to part-time marketers, other types of resource influence the quality and value perceived by the customer and are hence important from a marketing perspective. Technologies,19 goods, the knowledge that employees have and that is embedded in technical solutions, and the firm’s way of managing the customer’s time are such resources. By participating in the service process, the customers as individual consumers or as users representing organizations often become a value-creating resource.

In summary, from the customer’s point of view, in process consumption the solutions to their problems are formed by a process and a set of resources needed to create a good customer-perceived service quality. In addition, the firm must have competencies to acquire and/or develop the resources needed and to manage and implement the service process in a way that creates value for each customer. Thus, a governing system is needed for the integration of the various types of resources and for the management of the service processes. In the service marketing literature, the way these resources are managed and implemented in interactions with the customers is called the interactive marketing function. We shall return to this concept in Chapter 9 on managing marketing or customer-focused management.

Promises made by sales and external marketing are fulfilled through the use of all types of resources. In order to prepare an appropriate set of resources, continuous product development in its traditional form is not enough, because the service process encompasses a large part of the activities of the service firm. Instead, to enable the fulfilment of promises, continuous resource development including internal marketing and a continuous development of the competencies and the resource structure of the firm are needed. Internal marketing will be discussed in depth in Chapter 14.

SERVICE MANAGEMENT AND MARKETING: A CASE OF A MISSING PRODUCT

The conclusion of the discussion in the previous sections is that service businesses – service firms and product manufacturers adopting a service logic – do not have products (understood as pre-produced bundles of resources and features); they only have processes, including a set of resources of many kinds, to offer their customers. Of course, these processes also lead to an outcome that is important for the customer. However, as the outcome of, for example, a management consultancy assignment or hotel accommodation cannot exist without the process, and because from the customer’s perspective the process is an open process, it is fruitful to view the outcome as a part of the process. Both the process and its outcome have an impact on customer perception of the quality of service and consequently on customers’ value creation.

A major challenge for service providers is, therefore, to develop innovative ways of managing processes as solutions to customer problems. The value support that a firm can offer is not embedded in the resources used in the service process, but it emerges in customers’ consumption or usage processes, when they use these resources in interaction with the service provider in order to achieve an outcome for themselves. Models and concepts of service management – perceived service quality, customer-perceived value, service production systems, internal marketing and other models and concepts – have been developed to help managers cope with this challenge.

CUSTOMER-TO-CUSTOMER COMMUNICATION: EXPERIENTIALIZING SERVICE PROCESSES

The customers have many roles in the service process. In the previous section customers interacting with the service provider’s resources were considered participants in the process as co-producers. Furthermore, customers experience the service process and perceive the service they get. These are the traditional customer roles in service processes. However, with the emergence of Internet and mobile-mediated ways of interacting and communicating, such as Facebook and Twitter, customers can also interact during a service process while consuming the service. Twitter especially provides a means of on-the-spot interactions through live tweeting, where tweets can be responded to instantly or forwarded immediately to other persons. This, of course, has a dramatic effect on word-of-mouth, where customers can share experiences with a huge number of peers for their further consideration when looking for purchasing options. However, it also has an effect which changes the nature of service experiences and therefore also of service processes, and the perception of the service.

Kai Huotari, who has studied the use of Twitter during TV shows and ice hockey games on TV, introduces the term experientializing for this phenomenon.20 A group of people sharing an interest in, for example, a given TV show, who watch the show in different locations, establish a contact with Twitter and, using live-tweeting, share their experiences with others in the group. In this way the personal service experiences change due to the experience sharing throughout the process, through customer-to-customer communication. Because the service provider has no control over how the service is experientialized, the service experiences and how they are developing and changing through experientializing may cause new challenges. Of course, experientializing has existed before, for example when a group of people gather at home or in a bar to watch a TV programme, but Twitter and live-tweeting add a totally new dimension to this phenomenon.

The experientializing concept also helps to understand other consumption situations, where consumers interact, either in person or through live-tweeting or any other similar means, and even where a single consumer without any C2C interactions adds an aspect to the service process which is not originally part of the planned service. For example, a person reading a newspaper or book during a bus or train trip experientializes the travel process, and the experience is different from a trip without a newspaper or book, and therefore the service is also different.21 For example, cafés, train companies and airlines have offered newspapers and magazines to their customers, in order to make their service experience more enjoyable.

NOTES

1. Harvey-Jones, J., Making It Happen. Reflections on Leadership. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, 1989.

2. A range of such definitions is discussed in Grönroos, C., Service Management and Marketing. Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990.

3. Gummesson, E., Lip services – a neglected area in services marketing. Journal of Services Marketing, 1, 1987.

4. Grönroos, 1990, op. cit.

5. See Grönroos, C., Adopting a service logic for marketing. Marketing Theory, 6(3), 2006, 317–333.

6. Since the beginning of systematized research into service marketing in the 1970s, four generic characteristics of services that distinguish services from physical goods have invariably been included in articles and textbooks; that is, intangibility, heterogeneity, inseparability and perishability. This set of characteristics and the fact that services are described in relation to goods have seldom been disputed. In the Nordic School research this set of characteristics has never been used as such. However, lately the relevance of this way of describing services has been criticized. See, for example, Lovelock, C.H. & Gummesson, E., Whither service marketing? In search of a new paradigm and fresh perspectives. Journal of Service Research, 7(1), 2004, 20–41 and Edvardsson, B., Gustafsson, A. & Roos, I., Service portraits in service research: a critical review. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 16(1), 2005, 107–121.

7. For a recent discussion of the ownership issue, see Lovelock & Gummesson, 2004, op. cit.

8. A comprehensive discussion of classification schemes can be found in Lovelock, C.H., Classifying services to gain strategic marketing insights. Journal of Marketing, 47(3), 1983, 9–20. See also Grönroos, 1990, op. cit.

9. Wünderlich, N.V., von Wangenheim, F. & Bitner, M.J., High tech and high touch: a framework for understanding user attitudes and behaviors related to smart interactive services. Journal of Service Research, 16(1), 2013, 3–20. See also Berry, L.L. & Parasuraman, A., Marketing Services. Competing Through Quality. New York: Free Press, 1991.

10. Grönroos, C., What can a service logic offer marketing theory? In Lusch, R.F. and Vargo, S.L. (eds), The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate, and Directions. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2006, pp. 354–364.

11. As observed in the customer-dominant logic research stream, the question of when consumption starts and when it ends has not been problematized in the service management and marketing literature. See Heinonen, K, Strandvik, T. & Voima, P., Customer dominant value formation in service. European Business Review, 25(2), 2013, 104–123.

12. See Grönroos, C., Service reflections: service marketing comes of age. In Swartz, T.A. & Iacobucci, D. (eds), Handbook of Services Marketing & Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2000, pp. 13–16.

13. Peppers, D. & Rogers, M., Enterprise One-to-One. London: Currency/Doubleday, 1997.

14. See Schonfeld, E., The customized, digitized, have-it-your-way economy. Fortune, 28 September, 1998, 69–74.

15. Kotler, P., Marketing Management. Analysis, Planning, Implementation and Control, 8th edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1994. However, Kotler only included people in his triangle model and omitted the physical resource (technology, goods and systems) elements of the Nordic School approach to service marketing.

16. In a service context the marketing triangle issue has been developed by Mary Jo Bitner and Christian Grönroos. See Bitner M.J., Building service relationships: it’s all about promises. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23, 1995, 246–251 and Grönroos, C., Relationship marketing: strategic and tactical implications. Management Decision, 34(3), 1996, 5–14. Since then the service marketing triangle concept has been applied in several contexts. See, for example, Yadav, R.K. & Dabhade, N., Service marketing triangle and GAP model in hospital industry. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 8, 2013, 77–85.

17. See Grönroos, C., Marketing services: a case of a missing product. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 13(4–5), 1998, 322–338.

18. See, for example, Gummesson, E., Total Relationship Marketing. Rethinking Marketing Management: From 4Ps to 30Rs. London: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999.

19. Parasuraman has also recognized the importance of adding technology to the product marketing triangle, which he illustrates using a pyramid metaphor. See, for example, Parasuraman, A. & Grewal, D., The impact of technology on the quality–value–loyalty chain: a research agenda. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 2000, 168–174.

20. Huotari, K., Experientializing – how C2C communication becomes part of the service experience. The case of live-tweeting and TV-viewing. Helsinki: Hanken School of Economics, Finland, 2014.

21. See Huotari, op. cit.

22. This case is based on a situation that occurred roughly 25 years ago. However, because it is pedagogically the best case about the ‘missing product’ in a service operation that the author knows about, it is used here. Moreover, although the case company successfully solved their problems, situations like the one presented in the case study are not uncommon today.

FURTHER READING

Berry, L.L. & Parasuraman, A. (1991) Marketing Services. Competing Through Quality. New York: Free Press.

Bitner M.O. (1995). Building service relationships: it’s all about promises. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23, 246–251.

Edvardsson, B., Gustafsson, A. & Roos, I. (2005) Service portraits in service research: a critical review. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 16(1), 107–121.

Grönroos, C. (1990) Service Management and Marketing. Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Grönroos, C. (1996) Relationship marketing: strategic and tactical implications. Management Decision, 34(3), 5–14.

Grönroos, C. (1998) Marketing services: a case of a missing product. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 13(4–5), 322–338.

Grönroos, C. (2000) Service reflections: service marketing comes of age. In Swartz, T.A. & Iacobucci, D. (eds), Handbook of Services Marketing & Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, pp. 13–16.

Grönroos, C. (2006a) What can a service logic offer marketing theory? In Lusch, R.F. and Vargo, S.L. (eds), The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing: Dialog, Debate, and Directions. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, pp. 354–364.

Grönroos, C. (2006b) Adopting a service logic for marketing. Marketing Theory, 3(3), 313–337.

Gummesson, E. (1987) Lip services – a neglected area in services marketing. Journal of Services Marketing, 2(1), 19–24.

Gummesson, E. (1999) Total Relationship Marketing. Rethinking Marketing Management: From 4Ps to 30Rs. London: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Harvey-Jones, J. (1989) Making It Happen. Reflections on Leadership. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins.

Heinonen, K, Strandvik, T. & Voima, P. (2013) Customer dominant value formation in service. European Business Review, 25(2), 104–123.

Huotari, K. (2014) Experientializing – how C2C communication becomes part of the service experience. The case of live-tweeting and TV-viewing. Helsinki: Hanken School of Economics, Finland.

Khalifa, A.S. (2004) Customer value: a review of recent literature and an integrative configuration. Management Decision, 42(5), 645–666.

Korkman, O. (2006) Customer Value Formation in Practice. A Practice-Theoretical Approach. Helsinki: Hanken Swedish School of Economics, Finland.

Kotler, P. (1994) Marketing Management. Analysis, Planning, Implementation and Control, 8th edn. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lovelock, C.H. (1983) Classifying services to gain strategic marketing insights. Journal of Marketing, 47(3), 9–20.

Lovelock, C.H. (1991) Services Marketing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lovelock, C.H. & Gummesson, E. (2004) Whither service marketing? In search of a new paradigm and fresh perspectives. Journal of Service Research, 7(1), 20–41.

Parasuraman, A. & Grewal, D. (2000) The impact of technology on the quality–value–loyalty chain: a research agenda. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 168–174.

Peppers, D. & Rogers, M. (1997) Enterprise One-to-One. London: Currency/Doubleday.

Prahalad, C.K. & Ramaswamy, V. (2004) The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Unique Value with Customers. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Ravald, A. & Grönroos, C. (1996) The value concept in relationship. European Journal of Marketing, 30(2), 19–30.

Schonfeld, E. (1998) The customized, digitized, have-it-your-way economy. Fortune, September 28, pp. 69–74.

Wünderlich, N.V., von Wangenheim, F. & Bitner, M.J. (2013) High tech and high touch: a framework for understanding user attitudes and behaviors related to smart interactive services. Journal of Service Research, 16(1), 3–20.

Yadav, R.K. & Dabhade, N. (2013), Service marketing triangle and the GAP model in hospital industry. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 8, 77–85.

Zeithaml, V.A. & Bitner, M.J. (2000) Services Marketing. Integrating Customer Focus Across the Firm, 2nd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.