Consumer-Generated Content and Web 2.0

The media space has now changed its focus from product-centric to consumer-centric media exposure. The nature of the Internet has greatly added value to content and file sharing applications in the virtual space. This has positively shaped the creation and distribution mechanisms for consumer-generated content (CGC). With the focus now on consumers, the virtual space is highly personalized and consumers can tailor their media exposure to their specific needs and desires (Liang, Lai, and Ku 2006).

Why is tailored exposure important in the marketing world? When a user can tailor his or her exposure on the Internet, the release of information is according to the user’s provision. Further, through Web-based applications that collect information through CGC platforms (e.g., social networking sites [SNS]), information will circle around consumers rather than the publisher. This implies that privacy and security issues are at stake, therefore highlighting the importance of tailored exposure. Again, this is a move from publisher-centric to consumer-centric. As CGC activities continue to evolve and dominate the consumer market in terms of communication medium, there will be more and more applications that will be used with the Web 2.0 application.

Really Simple Syndication, also known as RSS, is a technology that enables a consumer to use and access information in a more manageable space that is both customized and relevant (www.usa.gov). Web 2.0 and other collective software is built on RSS as it gives consumers the flexibility and accessibly to create or simply use the information on the Internet, or both. With the explosion of online information, which eventually led to the creation of CGC, company-based message producers are slowly losing their power to CGC. This power shift in the industry has called for greater control of the social media as well as for gaining a deeper understanding of consumers’ motivation to create and consume media content. The greater the reliance on CGC, the greater the variety of choices available for consumers (Severin and Tankard 1992).

The relationship between Web 2.0 and CGC will likely increase the way people search for information, read, gather, and develop consumer information (Ye et al. 2011). This relationship between Web 2.0 and CGC provides a tremendous opportunity for e-commerce (Sigala 2008). Ye et al. (2011) posit that in e-commerce, CGC may serve as a new form of word-of-mouth (WOM) for products or services or their providers (p. 635).

Web 2.0 allows open communication with an emphasis on Web-based communities of users. Such an open communication enables more outlets for sharing different types of information. As users (consumers) utilize the Web 2.0 function, new platforms such as blogs and Wikis are born, which are considered components of Web 2.0. Often consumers see Web 2.0 as an online leisure activity platform more than a go-to information hub.

Categories of CGC

CGC houses several different platforms that are often referred to as social media. The use of social media on the Internet has changed the way information is searched and contributed (Williams et al. 2012). Although the term social media has multiple definitions, Blackshaw (2008) considers it an Internet-based application, also known as Web 2.0. This application is relevant to consumers’ activities such as “posting,” “tagging,” or “blogging.” Blackshaw and Nazzaro (2006, p. 4) claimed that CGC is “a mixture of fact and opinion, impression and sentiment, founded and unfounded tidbits, experiences, and even rumor.” CGC is produced, shared, and used by consumers who have the desire to share their knowledge with each other on products, brands, services, and issues (Blackshaw and Nazzaro 2006).

Kaplan and Haenlein (2010) categorized social media into six different categories for CGC: collaborative projects (e.g., Wikipedia), blogs and microblogs (e.g., Twitter), content communities (e.g., YouTube), SNSs (e.g., Facebook), virtual world games (e.g., World of War Craft), and virtual worlds (e.g., Second Life). Regardless of the classification of each social interactive platform, each social media type has its strengths and designated purpose. Qualman (2011) stated that 93 percent of businesses use social networking for their marketing and branding activities. This is an indication of how many potential clients are attracted toward online surfing and how a SNS like Facebook increases a company’s equity and its brand value.

As a part of an organization’s promotional effort through more diverse communication outlets, many organizations have taken advantage of social media for their CGC, turning it into a new hybrid component of their integrated marketing communications (IMC) effort. By using social media, organizations are able to establish strong and lasting relationships with their consumers (Mangold and Faulds 2009; Weinberg and Pehlivan 2011). Social media has a unique ideology and technology as it allows consumers to generate and exchange content on the foundations of Web 2.0 (Kaplan and Haenlein 2011). There are a variety of social media outlets built on an information-sharing format. These SNSs include Facebook, Pinterest, YouTube, and Flickr (creativity works-sharing sites), Wikipedia (collaborative sites), and also Twitter, a microblogging site. Among these various social media sites, SNSs have been the most popular format among researchers, practitioners, educators, and policy makers (Ellison and Boyd 2013; Roblyer et al. 2010).

Further, many consumers have started using social media in place of e-mail. Since 2006, the instant messaging options have already outpaced e-mail as an online activity (Pew Research Center 2007). The nature of social media encourages high levels of self-disclosure as well as a wider social presence. These social media forms have enabled consumers to connect with each other easily and quickly. Consumers who are participants of social media share opinions and thoughts on the products and services they purchased or consumed as well as exchange information on a particular topic. Owing to the nature of social media, platforms like Facebook have become the consumer’s destination for consumer-to-consumer (C2C) conversations, as well as the CGC widely known as WOM. Further, several researchers (Kim and Gupta 2012; Sweeney, Soutar, and Mazaarol 2008) recognize the importance and influence of WOM on consumers’ decision-making process.

Characteristics of CGC Consumers

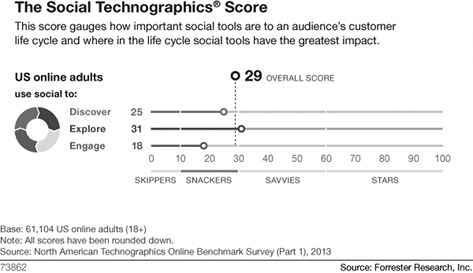

In this section, we will look at the different characteristics that shape the behavior of each CGC consumer through social media. Several companies use social media to host their CGC. Therefore, it is important to look at social media users as they usually consume, participate, or contribute content via social media platforms. According to Forrester Research (blogs.forrester.com), social media users are classified by what is known as Social Technographics® Scores. Since 2007, Forrester’s Social Technographics Ladder has been one of the widely used tools in determining the different types of social media users. However, as technology advances and people become more adaptable toward social media usage, marketers are no longer in the position of understanding whether their customers use social media. Rather, they are challenged with understanding how effective social media is in interacting with their customers.

Since the maturity of the social media consumer market, Forrester developed a new framework that helps marketers’ analyze people’s social behavior and benefits from this social media evolution. This model is known as the Social Technographics® Scores (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 U.S. Social Technographics Score

Source: Forrester Research Inc., http://blogs.forrester.com/

Permission to use image was sought and attained from Forrester Research, Inc.

According to Forrester Research, this scoring system helps marketers to develop a successful social strategy in two stages:

- 1. Overall score, and

- 2. The discover, explore, and engage factors.

The overall score refers to how active consumers are in using social tools as well as how important these social tools are within their customer lifecycle and how willing they are in engaging brands on social media.

Like the Social Technographics Ladder, there are also audience categories. These categories range from high engagement with brands on social media to low engagement with brands on social media. Next, we look at these categories:

Social Stars—audiences who score high in their engagement with brands on social media will fit into this category. When a company has such a category in its customer base, it is an indication that it is time to make social media a centerpiece of the company’s marketing effort.

Social Savvies or Social Snackers—audiences who fall into this middle range category comprise individuals who use social media moderately. In other words, if a company finds that the majority of its audience falls in this category, it should start thinking of using social media as a supporting tool in their marketing plan.

Social Skippers—audiences who belong to this category are known to be inactive social media users. In other words, companies that have the majority of their customers in this category should start shifting some of their resources from social media to other channels. This is largely due to the communication channel preferences of these customers. Moving certain resources (e.g., financial resources) into traditional media such as TV may prove to be influential for a successful marketing plan.

The second stage highlights the factors that inform companies where social tools are important in a marketing plan. Once companies have a better understanding of their social tool usage (heavy to light) in their marketing plan, they will need to know the types of social interactions being sought by their target consumers. Ranging from high to low, if a company’s customer base is generally comprised of high discover factor individuals, it is likely that the company will have its customers’ permission to use social reach strategies such as WOM.

However, if the explore factor is the highest, it indicates that the targeted consumers have a high preference for social interactions. Thus, investing in social depth strategies such as the development of a virtual community and implementations of reviews to the website is highly preferred.

The last factor in the second stage is the engage factor. If the company’s consumer base is mainly filled with consumers with a high engage factor, then SNSs such as Facebook should be favored in its social relationship strategy. In other words, companies need not invest in white label social media platforms.

CGC—eWOM

The purpose of WOM is to allow consumers to exchange information with each other. It is essential in influencing their attitudes toward a particular product or service (Katz and Lazarsfeld 1995; Solomon 2014). WOM is believed to be a very powerful marketing communications tool as it creates a higher level of trust compared to company-generated persuasive messages. Companies are often biased in the messages they deliver, solely because they want to generate more sales. Thus, consumers often rely on CGC (i.e., WOM) when they search for information that forms the basis of their purchasing intent. WOM is no longer a face-to-face occurrence. It has expanded into the virtual world, creating a whole new platform for informal sources. Electronic WOM, henceforth referred to as eWOM, is facilitated by Internet-based media.

eWOM is defined as a statement that represents either a positive or negative statement made by potential, actual, or former customers on a product, service, or company. These statements are readily available to a large group of people via the Internet (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2004). eWOM occurs on a wide variety of virtual communication channels, including SNSs, blogs, e-mails, C2C review sites, discussion board or community forums, and instant messaging (Dwyer 2007; Hung and Li 2007). As eWOM spreads in the virtual world through these channels, marketers can take advantage of such a platform to gain a better understanding of consumers’ decision-making processes, attitudes toward a product, brand, or service as well as the company’s website. In fact, many companies create their own page, for example, on Facebook, to have a closer connection with their customers to meet the shift from company to customer demand. This is also known as relationship marketing.

The Case of L’Oréal and Estee Lauder

According to Shen and Bissell (2013), social media has been used, particularly Facebook, to “increase brand awareness and reinforce brand loyalty” (p. 646). They argue that the use of social media has changed consumers’ decision-making process which has led companies to shift their focus from being product-centric to consumer-centric, and from information delivery to an exchange of information (p. 647).

Content creation is no longer a one-sided effort (e.g., company), rather it is combined with eWOM approaches, which are consumer-contributed (i.e., CGC). Although Shen and Bissell’s (2013) study was situated in the beauty industry, it revealed a paucity for theoretical and empirical investigation in several other industries. Sengupta (2012) claims that an SNS, such as Facebook, has become one of the fastest growing ways for companies and businesses to promote their brands and products and to turn a one-way communication into an interactive model of communication. Social media networking sites such as Facebook have created “a mature WOM viral scenario for product promotion and brand management” (Shen and Bissell 2013, p. 647).

Often, companies and business use social media to promote their information. However, “it is not the only way to make profits” (Shen and Bissell 2013, p. 648). Rather, the collection of thoughts and advice from consumers via other activities such as Q&A or calendar sharing may be perceived as a more beneficial way to achieve brand loyalty.

Evidently, consumers’ willingness to contribute toward posts, such as a “like” or “comment,” on social media shows the strength and uniqueness for brands. Shen and Bissell (2013) added, eWOM is not a one-sided communication, either from the company or from the consumers. It needs to be interactive and engaging. In addition, Galloway (2012) found that “numb responses times … led to a decline in engage rates of almost 50 percent” in just one year (p. 2). In other words, timely responses by companies toward consumers are vital in keeping the eWOM interaction active. As this eWOM content accumulates, companies will take advantage of its presence to build traffic to its website as an interactive form of communication which leads to the creation of CGC.

CGC—Blogs

One category of CGC is a Weblog, also known as blog, which is a diary style website that generally offers observations and news that are posted in a chronological order. Within these blogs, there is space available for commentary, feedback from readers, and a column for recommended links. Bloggers are scrutinized in the messages they post on the blogging universe, also known as the blogsphere. Although certain studies examine the credibility of online media, scholars have not paid attention to the credibility of the users that judge the quality of Weblogs (Johnson and Kaye 2004). Although Weblogs have received criticism, their popularity is undeniable. According to Johnson and Kaye (2004), the number of blog users increased from an estimated 30,000 in 1998 to at least 3 million by the beginning of 2004. Another reason for the blog’s increased popularity is the content it generates. Many blog users are interested in politics and therefore are easily persuaded by tech-savvy politicians. This niche market of blog users may be small but their influence may have exceeded the expected readership. Despite the initial aggression by many journalists, they have gradually seen the blog as a trustworthy source of information and do not hesitate to rely on them for relevant information and inspiration for ideas. One of the main reasons for the blogs’ dependability is its capability in bringing stories to light when traditional media refuses to. Cho and Huh (2010) argued that even though the use of blogs by corporations is still small, the number is increasing. Blogs by corporations (hereafter corporate blogs) have a twofold purpose: internal and external. Companies use internal blogs as a communication tool to enhance internal communications among their staff as well as external stakeholders.

On the other hand, corporations also offer consumers an opportunity to contribute toward their corporate blogs by reviewing products, services, and technologies offered by the companies of which they are customers. Some of these consumer bloggers are compensated, whereas others are voluntary (Ghazisaeedi, Steyn, and Van Heerden 2012). Droge, Stanko, and Pollitte (2010) posit that blogs have been an important communication tool as they allow information distribution through the Internet as well as have knowledge-sharing capability. Communication and marketing companies use blogs as a market research tool to analyze the current market place and as an evaluation tool for their business’ welfare (Xifra and Huertas 2008). Further, blogs allow consumers to cocreate value with companies by sharing their experiences about their purchased products with the company (Droge, Stanko, and Pollitte 2010). On the contrary, since blogs are generally contributed by consumers (Mutum and Wang 2010), blogs have enabled consumers to take control of the products’ popularity by allowing them to contribute with instant feedback and using the blog as a strong eWOM (Droge, Stanko, and Pollitte 2010).

Consumer-Generated Websites—Collaborative Sites

Wikipedia is a CGC platform on which consumers can contribute content that are of interest to them. For someone who is new to online contribution, it may seem a little overwhelming with the amount of content that is posted on the site. It is not true that a contributor needs to know everything and anything about posting content on Wikipedia. It is important to know how to use our common sense when we write and edit content. Wikipedia allows contributors to create, revise, and edit articles. These features encourage contributors to contribute content to its best accuracy.

Many college professors use Wikipedia as a part of their lesson plan; for example students are required to create their very own encyclopedia as part of their assignment. Although there are protocols in using Wikipedia, one cannot break the platform. The good thing about Wikipedia is that it is a work-in-progress project. Very often, students are asked to work collaboratively on their classmate’s work to edit any incomplete or poorly written pieces. As we practice and as time permits, a poorly expressed article will become an excellent piece of article.

Wikipedia has also been a popular collaborative hub for several companies including Pixar and Red Ant. Red Ant, a web design company based in Sydney, Australia, uses Wikipedia as the main collaboration hub between its employees and its clients. Red Ant explains that this hub is used to share and gain approval from its client for a particular design. In addition to back and forth iterations among developers, the client also gets involved by e-mailing the link of a diagram or adds comments on the page (stewartmedar.com). There may be opportunities for product marketing on Wikipedia, especially for larger companies. However, generally product marketers are unlikely to benefit from what they would find on a Wikipedia page (King 2011).

The Core of CGC

The popularity of CGC among consumers is soaring (DeMers 2014). The reason for such popularity is partly due to the ease of usage and perceived usefulness of CGC (Ayeh, Au, and Law 2013). With the principles of human–computer interaction, the software design for a majority of these CGC platform supports users’ activities. Furthermore, Preece (2000) and others (Flavián, Guinalíu, and Gurrea 2006; Preece, Nonnecke, and Andrews 2004) argued that if the software has great usability, and is consistent, controllable, and predictable, users will be able to use the platform with ease, with efficiency, and have a pleasant experience. There are two features that predominately attract users to participate in CGC: ease of use and perceived usefulness. These two features are arguably strong determinants in enhancing consumers’ need for satisfaction.

Ease of Use

An important feature when attracting users to a CGC platform is the ease of usage. Ultimately, if a product or service is easy for a consumer to use, be involved with, or produce, it will be key to attracting more people. On the other hand, if a product or service has several complicated steps to maneuver, then users will just get frustrated and eventually give up the idea of using the platform. This brings us to the topic of why consumers are so attracted to Wikipedia. For science-based knowledge, users often flock to Wikipedia due to its convenience. Although Wikipedia has a drawback in that its accuracy is questionable when compared with other sources, people rank convenience over accuracy (Head and Eisenberg 2010; Rainie and Tancer 2007). Companies that benefited from using Wikipedia include IBM, Sony Ericsson, and Red Ant (www.stewartmader.com).

Another example is the use of YouTube. Regardless of whether a person is uploading or watching a video for a particular purpose, the outcome from this source is phenomenal. People often weigh the gains and losses for any decision they make (see Prospect Theory). Thus, if a user is able to find out more information and gain more knowledge from an easily accessible source, then that source will highly likely attract people to consume, participate, and produce. Essentially, the meaning of easy usage means to put in little effort (e.g., few clicks for uploading a video) for a greater output (e.g., abundance of information).

In theory, Bentham’s utility theory (Read 2007) has been used to explain this “ease of use” phenomenon. This theory is an evaluative framework for alternative choices made by individuals or groups, or institutions. The definition of utility refers to the level of satisfaction that each choice provides for the decision maker. Essentially, this theory assumes that any decision is made based on which choice has the highest utility (i.e., satisfaction) for the decision maker. This rationale is based on the utility maximization principle. Fishburn (1968) explained that when utility theory is used on a practical perspective, people’s choices and decisions are the main concerns. This theory also explains “people’s preferences, judgments of preference, worth value, and goodness or any of a number of similar concept” (p. 335).

We are currently in a digitally reliant society where there is a wealth of information available at our fingertip; wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and there is a need to allocate the attention efficiently through the abundance of information in order to consume it. Thus, with a simple design and accessibility, it will maximize people’s satisfaction at the same time allowing a degree of control. CGC has been serving its importance by not only helping people with attention allocation but also providing great gratification.

CGC platforms have become a virtual gathering place for different types of audiences and have inevitably changed traditional media perception. With the presence of social media, CGC has become more and more appealing to large groups of individuals because of its usability and level of gratification obtained from consuming, participating, and producing CGC. CGC is not only a source of entertainment for people, but it can also serve as a source of education. CGC is multifaceted as it offers a wide variety of resources for people with different needs. With the nature of CGC, individuals have changed their way of online searching and the concept of trust with online information. Despite the multiple uses of CGC, these sites are often utilized the most for entertainment purposes. For example, YouTube has changed the perception of entertainment. It is no longer the traditional movie night or Saturday Night Live shows; rather entertainment has become a light and digestible snack that users can consume at a fast speed and at a high frequency. In addition, in regards to mood management, people may seek to use CGC to comfort them, leading them to a whole different world, or it could create an emotional stir. This alteration of mood states is still a prevailing argument.

Despite the positive attributes of CGC, several questions still remain: Is the ultimate goal of CGC to build up a community or to enhance one’s self-concept (e.g., self-expression)? With users sitting in front of a screen, is it really an engagement with society? If they were to go offline, can these individuals be engaged at the same level? If they can’t, wouldn’t that be a contradiction of the core purpose of CGC?

Perceived Usefulness

Online consumer reviews contain open-ended viewpoints and ratings from consumers (Park and Kim 2009). Open-ended viewpoints are textual assessments of the positives and negatives of the quality of a product or service. Ratings, on the other hand, is a summary of numeric statistics. According to Cheung, Lee, and Rabjohn (2008), the perceived usefulness of a review has been found to be a significant predictor of consumer’s intent to comply with a review. Mudambi and Schuff (2010) defined perceived usefulness as “a measure of perceived values in the purchase decision-making process” (p. 186). Ratings that are on the extreme end of the evaluation scale (i.e., 1–5 star ratings) are perceived to be more useful than neutral ratings (Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil et al. 2009). Sen and Lerman (2007), on the other hand, found that the usefulness of reviews is also reliant on the popularity of product ratings (e.g., negative reviews are more impactful than positive reviews).

Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil et al. (2009) argued that the usefulness of reviews goes above and beyond the star or numerical ratings or both. Willemsen et al. (2011) added that the important drivers of a review’s perceived usefulness can be based on three content characteristics within the open-ended reviews—that is, “expertise claims, review valence and argumentation” (p. 21). They also found four characteristics that have a significant effect on consumers’ perceived usefulness of online consumer reviews. Purchase price, one of the four characteristics, had a significant negative effect on perceived usefulness of online consumer reviews. The remaining three characteristics—review length, star rating, and location disclosure (i.e., residential location of the reviewer)—had a significant positive effect on perceived usefulness of online consumer reviews. Willemsen et al. (2011) concluded that longer reviews that have more star ratings and contain information on the reviewer’s place of residence are considered more useful—“as are reviews of relatively low-priced products” (p. 29).

In addition, Pollach (2008) discovered that when reviewers claim to have expert knowledge on a particular product, their evaluation of the product under consideration is likely to be perceived as useful. Furthermore, Hu and Sundar (2010) explained that the authority heuristic often steers people’s judgment of a review. Review valence was also found to have a marginally positive main effect on perceived usefulness (Willemsen et al. 2011). Review valence is determined on the basis of whether the review offers a positive or negative comment. Willemsen et al. (2011) argued that “the more positive (negative) the valence of a review, the more (less) likely people are to purchase the reviewed product” (p. 22). In addition, they also found out that review valence is not consistent across all product types. Their results showed an interaction effect—demonstrating that the negative effect was prevalent for experience products. Referring back to classic literature, Aike and West (1991) used a slope analysis to demonstrate that the perceived usefulness of consumer review valence had a negative effect when the product discussed falls under the experience product category. Whereas, a positive effect is prevalent when the product discussed falls in the search product category.

Schindler and Bickart (2005) claim that argument density is a significant predictor of consumers’ perceived usefulness of online reviews. Their results show that online reviews are regarded as more useful when the product evaluation is accompanied by a high number of arguments. Similarly, their results also show that argument diversity was also a significant indicator of perceived usefulness of online consumer reviews. Argument diversity for online reviews means that reviews for a product should be spread between positive and negative in order for consumers to perceive its usefulness in their decision-making process.

Furthermore, negative information does not impact all products; rather, their results show that review valence is dependent on the type of products being evaluated (e.g., experience vs. search products) (Willemsen et al. 2011). Contrary to previous research, negative eWOM showed a stronger impact on consumers’ judgment and choices compared to objectively equivalent positive eWOM (Godes and Mayzlin 2004; Park, Lee, and Han 2007). Willemsen et al. (2011) found that negative eWOM was only effective on experience products and those reviews were perceived to be more useful than positive reviews. On the other hand, they discovered that when the product evaluated is classified as a search product, only positive reviews were perceived to be more useful. The results were explained using consumers’ attributes such as familiarity and likings—they argue that positive eWOM becomes more prevalent in the situation where the product being evaluated is a search product because when such an evaluation is done, consumers tend to infuse their familiarity and likings with the product attributes before making the actual purchase. It is important for marketing practitioners to know which type of eWOM they should address depending on the type of products because of the differences in pre-purchase performance veracity (Park and Kim 2009; Xia and Bechwati 2008).

Based on Willemsen et al.’s (2011) results, consumers’ perceived usefulness of online reviews includes the characteristics of the reviews on the surface level (e.g., star rating, reviewer identity disclosure). They extended on previous research (Chevalier and Mayzlin 2006; Ghose and Ipeirotis 2009) and explained that these characteristics are regarded as heuristic cues, which can be processed with minimal effort. Furthermore, they used the Elaboration Likelihood Model (Petty and Cacioppo 1984) to argue that consumers use argument density and diversity to evaluate the usefulness of a review as these indicators are more central to the content of the review, which requires more elaborate processing (Petty and Cacioppo 1984). In addition, textual content of reviews is able to convey the subtle online interactions between consumers that is not attainable through star ratings (Resnick et al. 2000, p. 47).

Since argument diversity and density has an impact on consumers’ perceived usefulness of online reviews, it suggests that web-masters of a website should consider a suitable format or layout for review spaces that encourages consumers to express both their positive and negative opinions and thoughts. By structuring the reviews in such a way, consumers will be able to fully utilize the comments during their decision-making process.

Consumer’s Attitude Toward CGC

In relation to CGC, a consumer’s attitude toward CGC derives from his or her perception of the value of the content, which then relates back to his or her beliefs and feelings. Studying the psychological aspect of a consumer’s attitude with his or her relationship is no easy task. This is because of the various types of behavior that consumers would experience. Therefore, Fazio and Towles-Schwen (1999) categorize consumers’ thought processes into spontaneous and deliberate. They explain that when consumers are experiencing spontaneous thought processes, the reaction and attitude formed will be passed on to their perceived image of the object in their immediate surroundings. They add that when a consumer experiences such a thought process, generally there are environmental cues that triggers a memory for the consumer, which indicates an imminent behavior. Any resulting behavior of a consumer is dependent on his or her attitude at a given time in a given situation. The consumer’s behavior is also reliant on his or her past experiences with a similar situation (e.g., memory).

On the other hand, when consumers experience the deliberate processing approach, they do not place emphasis on pre-existing attitudes triggered by the environmental cues. Rather, they develop and build on raw data presented in the situation. Since this method of processing is considered deliberate, consumers form their attitudes based on their evaluation of the data. Essentially, what this means is that consumer will think about the potential consequences of engaging in a particular behavior when they consider the type of attitude they should form. It is reasonable to assume that the consumption of CGC is a deliberate behavior because it involves data-driven decisions. According to Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975) theory, attitude has a positive relationship with behavior. Thus, if there is a positive interaction regarding a piece of CGC, the consumer’s attitude toward CGC consumption and creation should become more positive.

Between the two types of CGC thought processes, the deliberative processing route will lead to consumption behavior. However, if the CGC behavior is spontaneous then it will lead to creation behavior. Spontaneous type of behavior is often triggered by environmental cues, which suggests that an attitude and an action are required. Nonetheless, in order for consumers to embark on content creation, it will require both previous experience and the timeliness of the situation. Thus, if consumers have a positive attitude toward CGC in general, they will likely have a positive reaction toward creating their own CGC. This positive reaction will have an impact on how much consumers attempt to consume CGC and how much they are likely to create it.

Collaborative Behaviors: Consumption, Participation, and Production of CGC

The reason why consumers are intrigued with CGC concerns their internal motivations (Eastin and Daugherty 2005). CGC consumption is regarded as a deliberate and active behavior. This suggests that the internal motivation of such behavior happens because it is out to meet the needs of the consumers. This motivation forms an attitude, which ultimately influences behavior. Consumers’ motivation varies, which means that depending on the level of motivation (high vs. low), consumers may choose one behavior over the other. For example, if the motivation for the consumer is to consume (i.e., look at) consumer-generated media and not to create, then it can also imply that the difference in the willingness to experience CGC is different. This is because there is a difference in the level of involvement (high versus low between the willingness to consume and the willingness to create content online).

The three suggested ways in which consumers are motivated to use CGC include: (1) consumption, (2) participation, and (3) production. Consumption is defined as usage of content (e.g., watch, read); it does not include participation. The second way, participation, acts as a two-way street. In other words, there is an interaction among the users and an interaction between the user (i.e., consumer) and content. This latter interaction includes activities such as posting of comments, sharing with others, and peer-to-peer music sharing. Production, on the other hand, is the creation and publication of one’s personal content such as photos and videos. In other words, it implies self-produced content that is contributed online. In essence, when consumers choose to consume, they are browsing online for information and entertainment purposes.

These collaborative behaviors (consuming, participating, and producing), although separate, are actually interdependent of each other. These activities are representative of a gradual engagement with CGC. When an individual is exposed to a new activity, the level of involvement will be very minimal. In the context of SNSs, consumers begin their involvement as consumers or lurkers. In order to proceed to the next step of involvement, people visit the CGC sites to consume content, absorbing information but not comfortable to participate.

After a period of familiarization, consumers will eventually come out of their shell and begin to participate through interaction. Apart from a C2C interaction, information consultation is also a type of interaction. With such an interaction in place, consumers will gradually establish their position, building and maintaining social relationships with people in the virtual world. In the last phase, which is when consumers are very comfortable with the social media platform as well as self-identification, they will start to product content. This behavior is also regarded as the highest level of involvement in a CGC activity.

When consumers start to produce content and share it in their online communities, it is an indication of the their self-expression and self-actualization (Heinonen 2011; Shao 2008). It is important to note that not every consumer will follow the consecutive phases of establishing their identity online. Though, it is a natural path for any newcomer to follow, some people may have a higher level of confidence in producing their own original content. For example, a consumer may not feel the need to respond to a fellow consumer online, but is comfortable with producing and publishing his or her original work online. With the large amount of information published online, it may be assumed that there is a large number of consumer-producers. However, this assumption is false. Instead, the majority of consumers remain lurkers, and minority become contributors.

One of the main reasons for consumers to contribute their production online is to attract readers or lurkers. These contributors hope to solicit two-way responses: for example, comments and content dissemination to other CGC consumers. When there is a two-way interaction among CGC users, they are able to fulfill their social interaction needs, and even form friends within the virtual communities. The presence of responses for any content also encourages more creation from the original producers.

The activities of consumption, participation, and production comprise the lifecycle of consumers’ CGC behavior. Since content production attracts the attention of several consumers, large amounts of information are available for people to consume and entertain themselves. Furthermore, participating is similar to consuming, in that it reinforces producers to produce more since there is a need for self-expression and self-actualization (Chen 2013). Nonetheless, it is important to note that the population of producers is just as important as the population of consumers. This is because without consumption or participation, there is no need or motivation to produce more content. Each consumer plays an important role in the CGC lifecycle. For example, participating consumers can interact with producers by posting comments, rating, and sharing with others. All these behaviors not only enhance consumers’ online experiences in the form of entertainment, but they also enhance knowledge (Gummerus et al. 2012).

Sometimes, comments from fellow consumers are easier to comprehend compared to information provided by the company’s sales representative or information posted on its website. Why? This is because these former or current consumers relate their experiences using their own words without resorting to jargon. For example, on YouTube, there is an option for the creator (person who uploads the video) to enable public comments. Consumers who view the comments could then freely write what they thought of the video or they could simply just use the comments to gain a better understanding of that content. Review sites such as Yelp have ratings as well as reviews as the core features of their service. These ratings, rankings, and reviews allow consumers to find the best deal in town or the most popular store. As for the “sharing with” function on social media, consumers may wish to share the knowledge or share the content with someone whom they think would appreciate this information or who shares the same interests.

Consumers’ Motivation in Consuming CGC

Studies have shown that there are motives to why people use social media (e.g., Bronner and de Hoog 2010a, 2010b; Yoo and Gretzel 2008, 2012). According to Graber (1993) and others (McQuail 2000), there two typical motives to why people use social media: (1) information seeking and (2) entertainment. Equipped with this knowledge of the motivation behind social media users, marketers are able to better target their intended audiences.

Information Seeking

People seek information online to raise their level of awareness on certain topics, knowledge about themselves, others, and even society. With this thirst for knowledge, CGC has been gaining considerable attention, for example, a CGC platform like Wikipedia. Although it is not academically “approved” for use due to its reliability issue, people frequently visit the site to obtain general information about subjects that are of interest to them. The reason behind the choice of Wikipedia is because information is readily available in a concise manner.

Few of the main reasons that several universities discourage the use of Wikipedia are its questionable integrity and the source of information. Anyone can create new topics or edit items as they wish. All information that is created is immediately available to the world. Referring back to the theory of self-expression, people who contribute to such CGC sites may develop a sense of self-importance. They believe that their contribution has an impact on society and their action supports their self-image as an efficacious individual (Bandura 2001).

Entertainment

The other purpose for use of social media is entertainment. Bowman and Willis (2003) argued that consumers who use the social network site such as Facebook, are learning “how to make sense of things from their peers on just about any subject” (p. 40). With the increase in the number of search engines available, CGC has been a main source of influence in how information should be “searched.” Blackshaw and Nazzaro (2006) noticed that when a consumer searches for something on search engines like Google, it is highly likely that a CGC site will surface first before any company’s website. Furthermore, consumers tend to trust fellow consumers more than professional advertisers or marketers. As compared to information seeking, marketers consider consumers who use social media for entertainment purposes as a more important target market (Rafaeli and Sudweeks 1997).

Despite the difference in definition between entertainment and mass media, Ruggiero (2000) and others (Lee and Ma 2012) posit that majority of the people tend to lump those two categories together. Although it may be incorrect to assume that entertainment and mass media are synonymous, the birth of YouTube triggers such confusion as it is one of the main mass media platforms used by people globally for entertainment purposes. Consumers visit the YouTube website and watch entertainment-related channels such as sports, music, comedy, and drama. Miller (2007) labeled social media platforms such as YouTube as a “snack food.” This synonym mirrors the digestible attribute of a typical snack: small, light, and compact. These so-called snacks are catered toward individuals who have time constraints. Miller (2007) argued that pop culture is consumed in “bite-sized” pieces just like cookies or chips. In other words, these snacks are consumed in minutes but over an increased frequency and at maximum speed.

Indeed, many of the YouTube videos are just a few minutes long. The reason for such a bite-size technique is to (1) entertain oneself without being tied to the screen for a long period of time, and (2) retain concentration span. YouTube is a very innovative entertainment idea as it is able to meet people’s need for high-speed entertainment without compromising on the quality and quantity of videos. It may be a desire for some to escape from reality and indulge in a carefree, relaxing, and enjoyable moment or even for emotional release (Katz, Blumer, and Gurevitch 1974). Thus, using CGC entertainment like YouTube is more favorable over traditional media such as television and magazines. Another benefit of using CGC entertainment is its power of altering prevailing mood states of consumers. Marketing companies thus take advantage of this ability of CGC entertainment to captivate their consumers in conveying messages on their product or service. With a positively regulated mood (e.g., happy), the acceptance level of digesting the advertised message will be higher than the message portrayed from traditional media.

Consumers’ Motivation in Participating in CGC

When a consumer chooses to participate, he or she will be engaged in social interaction and community development. There has been an enormous leap in the number of users active on SNSs. According to a Nielsen Social Media report (2012), in an average month, Americans spend approximately 7 hours on Facebook alone. If a consumer chooses to produce his own content, he then ultimately had the desire to express his inner self or what Maslow considers self-actualization. According to Johnson and Knobloch-Westerwick (2014), individuals “may select social media sites content with the motivation to regulate mood” (p. 33). Prior research determined that the maintenance and development of social capital fosters social media use (Ellison, Steinfield, and Lampe 2011), as well as aiding in reducing an individual’s loneliness and boredom (Lampe, Ellison, and Steinfield 2008). Furthermore, it has been researched that when an individual views his or her own profile, it boosted his or her self-esteem (Gentile et al. 2012). All these results are tied to a psychological theory known as mood management theory (Bryant and Davies 2006). Apart from boosting one’s self-esteem, individuals who are stressed can also view YouTube clips and find some relaxation. Bored individuals can search for excitatory materials, and through this method, they can bring their physiological arousal and affect back to optimal, comfortable levels. Consumers’ choice on YouTube is largely inclined to videos that are “most viewed” or “most rated.” This also suggests that YouTube has a broader range of stimuli choices when compared to traditional media such as television channels.

Participating for Social Interaction and Community Development

As discussed earlier, users play the role of consumers (see role theory) when using the media as a source of information. Apart from consumption for information retrieval purposes, consumers also participate by engaging and interacting with the content as well as with users on consumer-generated sites. So how do consumers interact with the content and other users or consumers on the same social media? Consumers interact with content when they (1) rate the content, (2) click on the “star” to save the sites onto their favorites list, (3) click on the “share” button to share the information with people they know, (4) post comments, and (5) post the content to their SNSs (e.g., Facebook wall). These are some of the examples of what is meant by consumer interaction. A C2C interaction on the other hand, as understood by the name, is interaction with other fellow users on the same SNS. The methods of communication include the following: e-mails, instant messaging, chatrooms, community boards, and walls. The consumer-content interaction may be considered as an indirect communication, whereas a C2C interaction may be considered a form of direct communication. Regardless of the contact (direct or indirect), these forms of communication are able to fulfill the consumers’ need for interaction (Chan and Li 2010).

As McKenna and Bargh (1999) argue, since the inception of the Internet, social media has become a place for social interaction. Back in the early 2000s, Internet websites such as Yahoo and Excite among many others, that provided electronic venues for people to communicate with people who don’t necessary know each other. These venues include chat rooms, instant messaging, message boards, and e-mails. With the emergence and growing popularity of different social media platforms, engaging in social media activities has become an integral of people’s lives worldwide. Regardless of whether it is a simple search on movie reviews, or obtaining advice for a major life decision, there are several different social sites available for different users for different purposes. Despite the growing popularity and strong presence of the social media, there is still a debate on whether the Internet can fulfill people’s interaction social needs.

Some scholars have viewed the Internet as an inherently antithetical contribution toward the nature of our lives. On the contrary, the Internet was perceived as a solution to reduce loneliness, decreased depression, hostility, and isolation. The Internet was also believed to be a tool that helps in enhancing one’s self-esteem in the society, encourage greater likeability among others (e.g. peers), as well as to promote a conducive environment for others to feel accepted by others in the society. It is also a tool to widen social circles (McKenna and Bargh 1999). How do we know that the Internet has wide acceptance and greater favorability over other types of media? By observing the success of CGC platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Pinterest, and many other SNSs, it is evident that SNSs have a positive perspective among Internet users. In the United States, more than 74 percent of online users are engaged on online social sites (www.pewinternet.org). Back in the early 2000s, social sites were primarily used to reinforce preexisting friendships or used to make new friends, or for both. Despite SNSs being criticized for causing individuals to be antisocial in face-to-face interactions, they have their own advantages. A few advantages suggested by Van Dijk (2006) was that since there is no distraction such as nonverbal communication, consumers are able to concentrate more on the content by reading, watching, or listening intently to the content. In addition, it also allows consumers to loosen up and maintain an informal conversation. Therefore, SNS has become one of the most acceptable CGC platforms where brands can engage with their target audience and vice versa (Ruchko 2014).

Virtual Communities

Online interaction is not just a come and go session where people keep their conversation short. It is also an opportunity where people’s participation contributes toward the development and maintenance of communities. For example, Starbucks has an established virtual community on Facebook. These virtual communities are formed when people of the same interests and concerns gather to carry out public discussions. These discussions are long to an extent where strangers become community members where they form a relationship with one another (Rheingold 2000). These virtual communities are places where individuals who share similar interests are able to voice their opinions and concerns in a nondiscriminatory environment. Furthermore, as explained by Tajfel’s (1982) Social Identity Theory (SIT), people feel a sense of belonging when they are associated with a group. Similar to a face-to-face group, virtual communities also allow members to feel that their feelings are being shared and their needs are met through their commitment with each other (McMillan and Chavis 1986).

Virtual communities can be created solely on a community site or they may be created on any SNS as a subgroup (e.g., Facebook). These communities represent an identity where people connect and interact regarding shared interests and support. In fact, these virtual communities can be perceived as important as physically located communities. Although scholars have determined that members have a set commitment that keeps the group going and the conversation alive, there is always the question of who initiates a conversation. According to Joyce and Kraut (2006), responding to C2C content is a useful first step in developing a virtual community. In fact, repeated actions could lead to positive reinforcement where consumers keep their posts constant. As long as there is a response on an initial post, the content provider will feel motivated to share more new materials. Thus, it is important for community members to be responsive to posts, regardless of the tone, to maintain meaningful content creation.

CGC is a platform that focuses on consumer-to-consumer or even company-to-consumer interactions. Individuals take advantage of the content and the presence of other human beings to create and develop an interaction. For example, LinkedIn has provided a large support for business professionals with business networking opportunities. Facebook, on the other hand, has provided support for social networking opportunities. Individuals fulfill their social needs through online interactions with others. When a relationship expands into a network, a virtual community is formed. People within this virtual community can share their interests, identity, and a sense of closeness. Since virtual communities are created around CGC, it is arguable that these virtual community members should respond to each other’s comments or contribution as that is the core activity to strengthen dynamic content creation.

Consumers’ Motivation in Producing CGC

For continuation of CGC, constant production is key. Without producing content, there will be no CGC available. Many ask the mind-boggling question as to how people are motivated to produce CGC. Before we discuss the motivations behind why consumers create content and post them on the Internet via various social media, we will first look at the overarching popularity of self-created entertainment. In the United States, majority of the self-published content is produced by youths. Consumers who belong to the Gen X group are also catching up on the trend and creating their own content on YouTube. The number of videos produced is on a considerable scale where individuals could actually earn a living from just creating YouTube videos. For example, there have been cases where consumers self-create videos on YouTube and become instant celebrities from sharing knowledge on how to put make-up. These individuals were scouted by make-up companies to promote the latter’s products on the former’s videos. Thus, CGC has grown exponentially and has become an outlet that is specifically designed for people to engage in a producing behavior.

Bowman and Willis (2003) explain that consumers may have the desire to produce content solely to inform and entertain other people. There are two underlying theories that attempt to explain the motivation behind CGC contributors. One is known as self-expression, and the other is self-actualization. Self-expression is defined as one’s own expression on their identity. Essentially, individuals who are self-expressing are highlighting their individuality. McKenna and Bargh (1999) added that this concept assumes that people need to present their inner-self to the external environment. The rationale behind such behavior is because they want to exhibit their true selves. Now, how is this concept a motivator for consumer contribution to social media? By being actively engaged in blogging, video castings, and other self-highlighting activities, it allows individuals to showcase who they are by reflecting on their behavior online. Self-expression can either be explicit or implicit. Consumers who choose to use self-expression from an explicit approach would conduct their behavior through direct self-disclosure, whereas the implicit approach will be to focus more on the choice of words, style, and topic (Shiu 2013; VanLear et al. 2005). Ultimately, consumers who contribute to social media willingly are individuals who have the desire to construct an image and to establish an identity for themselves (i.e., self-expression).

Criticism against consumers who try hard to self-express themselves to others are often from people who are trying to escape reality. Kokkoris and Kühnen (2015) argued that self-expression creates the sense of being excluded from humble beings, and other external factors such as sounds and emotions from our everyday existence. On the contrary, despite the cynicism behind why people want to self-express, this self-expression process can be seen as an attempt to control the impressions of how others see them (Bortree 2005; Dominick 1999). It is inevitable that we establish an image of a person even before we meet that individual in person. These images are created based on hearsay, gossip, and information that is not necessary true. Thus, as individuals, we engage in selective self-expression, even if the information transmitted through the communication process is rational. There will still be the selective impression that the sender has intended to engage in (Walther et al. 2009).

When individuals contribute toward social media, they often have an intention to exercise impression management. Their behavior is apparent in the context of the creation of personal home pages and blogs online. As all these activities are customized for each individual, who has a different objective of what type of impression he or she wants to make, he or she has the flexibility to stage an online performance through his or her personality. One way to ensure that the staged performance is circulated on the Internet is individuals to engage in marketing strategies where they present their “self,” hopefully to attract readers and build supportive relationships with their fans or followers on their personalized sites (Dominick 1999). Individuals who use personal home pages to express themselves fall into two categories. For those who want to use webpages as a self-expressive tool, you will find more personal information compared to those who want to use their webpages as a professional tool. Some personalized home pages serve as personal blogs or vice versa. Regardless of the activity, those who see a need to self-express will use their blogs as a self-reflective account where they post their personal experiences (Hollenbaugh 2010; Trammell and Keshelashvili 2005). It was noted that A-list bloggers are strong advocates of self-expression as they reveal more personal information than other bloggers.

Self-actualization motivates individuals to produce their own content on consumer-generated sites. Self-actualization is defined as the need to work on one’s identity while reflecting back on one’s personality (Harmon-Jones, Schmeichel, and Harmon-Jones 2009; Trepte 2005). Part of this self-actualization is to express oneself which is ultimately aimed at highlighting one’s own identity. As discussed earlier, several CGC users engage in creating and producing content (e.g., blogging, video cast) to achieve self-expression. Self-expression is all about how one needs to highlight him or herself and to show who he or she is. In addition, self-expression also allows one to control how a third party perceives him or her to be. Furthermore, what motivates individuals to produce contents is their self-actualization and self-concept. The product that is produced is a reflection of their need to be recognized, become famous, or simply because of personal efficacy. All these CGC engagement reasons are interrelated. These activities help fulfill both an individual’s social and psychological needs. It is important to note, however, that the path to consume, participate, and produce is a gradual process. Furthermore, not all individuals will go through all steps. Some may skip the second step and go directly to the third step. It all depends on the level of self-concept and confidence of each individual.

Self-actualization is the last need as designated by Maslow’s hierarchy in his pyramid of needs. Unlike the motive for self-expression, self-actualization is primarily an unconscious behavior (Aarts and Dijksterhuis 2000; Berridge and Winkielman 2003). However, it can also be regarded as a psychological motive that drives one to attain a behavioral goal such as online production. For example, a social media contributor may want to seek recognition or personal efficacy (Bughin 2007). With accessibility, many social media users begin to dream about achieving instant fame. These regular social media users’ use CGC platforms to publish their content with the primary motivation of fame. Take American make-up artist Michelle Phan as an example. She rose to fame through her blogs and has engaged in YouTube channels demonstrating make-up techniques since May 2007. With such exposure, Michelle has since gained recognition in the make-up industry and has been an endorser for some well-known make-up brands such as Lancôme and L’Oreal.

With large traffic on YouTube and other sites, many people are optimistic of becoming famous content producers someday. Thus, there will no doubt be an increase in the number of self-produced videos on CGC sites.

Consumers’ and Companies’ Perspectives on CGC

CGC can be presented in the form of “online testimonials, product reviews, and consumer-generated commercials” (Rodger, Thorson, and Jun 2014, p. 199). Such CGC is often referred to as customer evangelism (Muñiz and Schau 2011). These online reviews can either have a direct or indirect effect on consumers’ decision to purchase a product or service (Ertimur and Gilly 2010). These activities are however not considered commercially motivated.

As consumers get more critical and skeptical about what products they purchase, the Internet becomes the source in their decision-making process. Regardless of the motivation behind Internet use, Internet users are encouraged to rate and review different kinds of services and products that they have had experience with. These types of reviews are known as consumer-generated eWOM. eWOM has been defined as “any positive or negative statement made by potential, actual or former customers about a product or company, which is made available to a multitude of people and institutions via the Internet” (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2004, p. 39). It is a type of online advertisement that takes advantage of the CGC platform.

Marketers have had the luxury of spreading commercialized information widely till the introduction of the Internet. From WOM to eWOM, the Internet has revolutionized how consumers obtain information and how quick and easy it is to obtain this information online. Spreading information online was once termed as “e-fluentials” (Sun et al. 2006) till 2004 when consumer-generated eWOM grabbed the spotlight (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2004). The main purpose for the birth of eWOM is to reduce the risk and the misleading information presented by private advertisements. eWOM is presumably contributed by a diverse array of “experts” who offer advice about what to buy and what not to buy. Leskovee, Adamic, and Huberman (2007) concluded that eWOM is of great value in stimulating advertisements.

According to Cantallops and Salvi (2014), there are five main reasons why consumers would contribute reviews: self-directed, to help other consumers, social benefits, consumer empowerment, and to help companies. On the other hand, Casaló, Flavián, and Guinalíu (2010) found that consumers’ intention to participate in online communities is dependent on the characteristics of the community. In other words, consumers are more likely to join online communities if they perceive them to be useful with an easy-to-use platform, which helps to develop a more positive attitude. In addition to Cantallops and Salvi’s (2014) suggestion, Bronner and de Hoog (2010b) argue that consumer motivation is an influencing factor in the type of site consumers choose to visit. This motivation also drives the way consumers express themselves on review sites. Essentially, why, where, and what are the three “Ws” behind consumers’ intention to contribute online.

Impact of CGC from the Consumer Perspective

Several studies (Lee, Park, and Han 2011; Papathanassis and Knolle 2011; Sparks and Browning 2011) explore the various reasons on how CGC can impact consumers’ decision-making processes. Some results from these studies indicated that consumers perceive online reviews to be useful only when the “story” related in the reviews are on successes rather than on failures of a company’s endeavor (Black and Kelley 2009). However, in Black and Kelley’s (2009) study, they noted that consumers are more likely to give higher rating scores on helpfulness, when the story entails the company’s effective recovery. On the contrary, Sparks and Browning (2011) found that consumers seemed to be more influenced by negative information, especially when the overall reviews are negative. However, when positive contextual reviews are paired with ratings, the level of consumer trust and purchase intention increases. In addition, Sparks and Browning (2011) found that when contextual reviews are positively framed, based on interpersonal service, the level of trust from consumer increases as well.

In terms of credibility, Xie et al. (2011) found that personal identifying information of reviewers increases the perceived credibility of online reviews. However, when such personal identifying information is paired with ambivalent reviews, consumers’ intention to purchase a service or product decreases. Along with Xie et al. (2011) study, Loureiro and Kastenholz (2011) found that a company’s reputation is a more significant determination of loyalty than consumers’ satisfaction or delight. Although satisfaction and delight did not overpower the level of significance of reputation, these are the two distinct constructs in determining consumers’ loyalty.

According to Hardey (2011), reliability is a factor that shapes purchasing behavior. CGC can be deemed credible when the reviews are based on experiences and opinions of real consumers (Xie et al. 2011). As mentioned in other studies, CGC needs to be a two-way communication in order to be effective. For example, TripAdvisor participates in CGC activity. The company reviews and responds to any specific consumers’ review in an “equally open and visible fashion” (Hardey 2011, p. 762). Apart from reliability and credibility, indicators such as perceived trustworthiness, usefulness of CGC, and level of expertise (Black and Kelley 2009; Yacouel and Fleischer 2012) were also frequently referred to when there is a discussion on the effect of reviews on consumers’ perspective. Papathanassis and Knolle (2011) claim that the risk reduction during the decision-making process is related to the purchase of intangible and inseparable service bundles. These perspectives inevitably affect consumers’ decision-making process when consumers are trying to reduce the level of risk as much as possible (Kim, Mattila, and Baloglu 2011).

Gender also had a significant impact on consumers’ motivation to read online reviews (Kim, Mattila, and Baloglu 2011). Similarly, Toh, DeKay, and Raven (2011) found that women are more active than men in terms of information search activities. In addition, research shows that the presence of CGC has a strong impact on product valuation and purchase decisions (Cantallops and Salvi 2014).

Another important indicator of the impact of CGC is related to the accessibility (Sparks and Browning 2011; Xiang and Gretzel 2010) and comprehensiveness of reviews. Cantallops and Salvi (2014) claim that consumers “have a complicated task filtering and analyzing” (p. 48) information written in reviews. These complications include influencing factors such as tone, valence, framing of the review (i.e., what is read first), and peripheral information such as star ratings. All this information adds up to influence the overall consumers’ process of digesting the information they read through CGC.

Impact of CGC from the Company Perspective

Like CGC having an impact on consumers’ perspective, it is also regarded a determining factor for a company’s success. Several studies have analyzed the impact of CGC from the company’s perspective (Dickinger 2011; Yacouel and Fleischer 2012), by considering company-generated content, its content quality in the online environment, and its possibility of interacting with clients and generating a price premium (Cantallops and Salvi 2014). Cantallops and Salvi (2014) determined seven main impact factors on consumer’s perception of the company: generating loyalty; quality control and new procedures; revenue management; customer interactions, responses, and recovery; marketing strategies; target group communication; and online reputation comparison.

In addition, Loureiro and Kastenholz (2011) argued that corporate reputation has a significant impact on the customer’s perspective of the service capability of the company. They explained that this perception leads to a reliable representation of the service the customer has in mind. Furthermore, in order to have a good idea of the company’s service quality, customers often use several different resource platforms to search for more information. For example, Berthon et al. (2012) claimed that customers use direct company websites, official website cybermediaries, and customer review websites to evaluate the attributes of the company.

Other research found that with the increased number of communication platforms (Jahn and Kunz 2012; Toh, DeKay, and Raven 2011), companies are faced with both challenges and opportunities. With an array of new technological platforms available, consumers can compare the offerings of the same product from different companies based on prices or search for other alternatives within the same product category. Thus, for companies to compete for the same group of consumers, they need to establish a strong relationship with their targeted consumers.

Customer loyalty was a factor that was highlighted by CGC studies as well. Loureiro and Kastenholz (2011) measured customer loyalty using indicators such as intention to continue to buy the same product, repeated purchase, or willingness to recommend the product to others. However, Loureiro and Kastenholz (2011) found out that the degree of loyalty does not make a difference in consumers’ repeated buying behavior if the consumer has already fallen into the loyal customer category.

The availability of social media has posed both risks and opportunities for companies. However, if the company is able to analyze any prevalent problems, these risks maybe converted into opportunities for the companies (Dickinger 2011). The ability to manage negative CGC (e.g., eWOM) is critical for consumers to stay competitive in the market. Some analyses conducted by companies who were faced with negative eWOM helped companies to improve their product or service quality, the identification of needs highlighted by their consumers, and the implementation of new policies (e.g., return policies) (Loureiro and Kastenholz 2011).

Positive eWOM on the one hand can help improve a company’s positioning in the market. This competitive advantage could potentially allow consumers to change their pricing strategies (Yacouel and Fleischer 2012). However, if companies choose to ignore or address the negative comments, they could potentially dismiss consumers’ interest, which can subsequently affect their pricing strategy and revenue generation.

eWOM, regardless of it being positive or negative, is important information for companies and their wellbeing. As Berthon et al. (2012) posit, CGC has a significant influence on companies’ marketing strategies. eWOM is a CGC that can serve as a performance indicator for companies; companies can direct their energy toward a more profitable consumer segment, and they can also influence consumers’ loyalty while retaining existing consumers.

Consumer Engagement in CGC

Communication between companies and consumers is no longer just an activity. Rather, it is just the beginning of consumer engagement in CGC. In fact, consumer involvement is no longer an option for companies; companies need to move a step ahead and start engaging their consumers in any marketing activities that they conduct, that is, consumer engagement. Theoretical roots of the consumer engagement concept are referred to as the “expanded domain of relationship marketing” (Vivek, Beatty, and Morgan 2012, p. 129). Ashley et al. (2011) agree that relationship marketing is carried out through the examination of customer engagement. In the service industry context, Vargo (2009) refers to this notion as “a transcending view of relationships” (p. 378), which is the trend of the current consumer market. Companies can no longer survive in a goods-dominant marketplace. They are recognizing that the transcending relational perspective is consumer-centric or “other stakeholder’s interactive experiences taking place in complex, co-creative environments” (Brodie, Hollebeek, and Smith 2011, p. 106), or both. It is important to realize that this transcendental relationship does not end with just the consumers. A firm’s focus is on existing and potential customers, as well as the consumer communities and their “organizational value co-creative networks” (p. 106). Lusch, Vargo, and Tanniru (2010) suggest that interactive consumer experiences, which are cocreated with other players, can be regarded as the act of engaging. These co-creation experiences may range from product suggestion to product creation through CGC (e.g., feedback).

Definition of Consumer Engagement

The term “consumer engagement” has been defined differently by a few authors within the virtual brand community (Brodie, Hollebeek, and Smith 2011). Vivek, Beatty, and Morgan (2012) added that the definition differs throughout different disciplines. Thus, there is no agreement to whether one definition should be adopted over another. Consumer engagement may be described as the “intensity of an individual’s participation and connection with the organization’s offerings and activities initiated by either the customer of the organization” (p. 4). Customer brand engagement, on the other hand, refers to the “level a customer’s motivational, brand-related and context-dependent state of mind characterized by specific levels of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral activity in brand interactions” (Hollebeek 2011, p. 6).

CGC platforms such as the SNS embeds the ideology for eWOM. SNS is practically the tool for consumers to freely create and disseminate product-related information on their established social networks. Be it image-based or text-based, consumers are subconsciously spreading the word about a product or service to friends, family, and other acquaintances through the great vine (Vollmer and Precourt 2008).

Depending on the age of media consumers, the preference for one social media over the other will vary. For example, according to Pew Research Center (www.pewinternet.org), half of the Internet users that were young adults (53 percent) ranging from 18 to 29 use Instagram. Also, for the first time, the number of LinkedIn Internet users with college education reached 50 percent. Based on Pew Research Center’s Internet Project, social media usage ranking is as follows: Facebook (58 percent), LinkedIn (23 percent), Pinterest (22 percent), Instagram (21 percent), and Twitter (19 percent).

A social interaction engagement such as exchanging views on an opinion is not solely based on a consumer logging into an SNS. Rather, engagement includes some kind of social interactions, for example, commenting on a post or clicking “Like.” By engaging in such interactions, consumers naturally exhibit their preferences for a product and services along with their persona (e.g., profile photo). This identification can stimulate online communication, which will eventually turn into eWOM. These days, eWOM is not only facilitated through company review websites, but they are also included in SNSs. This is because SNSs have developed over the years to facilitate such activity. As eWOM communications are regarded as CGC, marketing practitioners should gain a better understanding of the relationship between SNS users and the frequency of social media usage. There are many variables that underlie the social factors that influence consumers’ engagement in the virtual world.

There is a lot of debate to whether eWOM is worth investigating. However, with changes in social media usage, it is fundamental for companies to investigate the cause of behavior (why and how). Furthermore, in order to stay competitive in the marketplace, it is essential for companies to understand the social relationship variables that affect consumers to be involved in CGC activity. Such understanding can help companies incorporate social media as an integral part of their marketing plan.