What Is Consumer-Generated Content?

With the introduction of the Internet, individuals have become increasingly dependent on their mobile devices as these devices give them access to the digital world in seconds. Regardless of whether consumers are trying to obtain, accept, or deliver information, or simply just searching for it, they are relying on the digital environment as their source for information.

The importance of consumer-generated content (CGC) has increased over that of companies’ self-published content in the online world. This suggests that online information has shifted from publisher-centric to consumer-centric. CGC, as suggested by the name, is driven by consumers. Consumers create or produce (or both) any type of content (e.g., reviews, videos, photos, etc.) and share it with the general public. The channel of distribution is primarily the Internet. With innovative means of communication, the potential for a company to reach its mass audience is high. With Web 2.0 technologies, websites are given more support with the creation and consumption of CGC. Some of these CGC platforms include YouTube, MySpace, Facebook, Wikipedia, blogs, and community forums. The advent of Web 2.0 technologies has offered CGC a large opportunity to target its niche market within the media landscape, which attracts “more than $450 million” in advertising revenue (Verna 2007).

In a technologically advanced society, consumers are gaining more control over their decision-making processes and the amount of media exposure that they want to experience. As the conventional media model becomes obsolete, researchers are trying to understand consumers’ motivational factors that drive them to go online to look for information. Severin and Tankard (1992) argued that due to this power shift, media theorists are changing their audience identification process by focusing on understanding why and how consumers use media rather than the theoretical effects of media on these audiences. This suggests that CGC has a strong impact on the media environment, which indicates the importance of understanding the motivation of consumers and creators behind creating and contributing such media content. As consumers around the world adapt to the use of the Internet, communication channels are gradually increasing, creating a better and smoother flow of communication between consumer-to-consumer (C2C) as well as business-to-consumer (B2C).

By definition, CGC refers to materials that are created and uploaded to any Internet sites by nonprofessionals (www.iab.net). This also means that the content is not contributed by an expert, but rather by a consumer who has first-hand experience with a product or service. With the introduction of high-speed Internet and search engines, CGC has become one of the prevalent forms of global media. In fact, it is one of the fastest growing commodities on the Internet. According to a platform status report by Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) (2008), in the year 2006, CGC attracted 69 million users in the United States alone. With such a large user population, the revenue of $1 billion in advertising in 2007 proved that CGC is a dynamic new medium in this new future.

In general, CGC focuses on product reviews and restaurant services especially for airline companies, cell phone services, restaurants, hotels, and resorts. Ye et al. (2011) and others (Hu and Liu 2004) noticed that the amount of CGC contributed online is extensive, to a point where companies pay CGC writers to contribute reviews on their company website or sites that have the company name mentioned (e.g., Yelp!). Some may think that online reviews do not have considerable impact on the sales of a product or the percentage of patronage from a customer. This assumption is definitely incorrect. CGC has proven to be extremely influential and it has the ability to fold a business.

From Wikipedia and blogs to Facebook, various information is spread across different Web 2.0 outlets. All these outlets are known as CGC or sometimes known as user-generated content. CGC is a more commercial label that demands more “nuanced, innovative, and exotic methodologies” (Hardey 2011, p. 13). Consumers are constantly retrieving instant information with the click of a button. As consumers gain power over the consumer market, companies are redefining their market reach, frequency, and consumer targeting. Social media has definitely taken a leap in capturing the intended audiences and building brand relationships. It has long overtaken the traditional, product-driven, one-way street in marketing communication. Moreover, the introduction of social media has adopted the approach of new information and consumer-driven objectives.

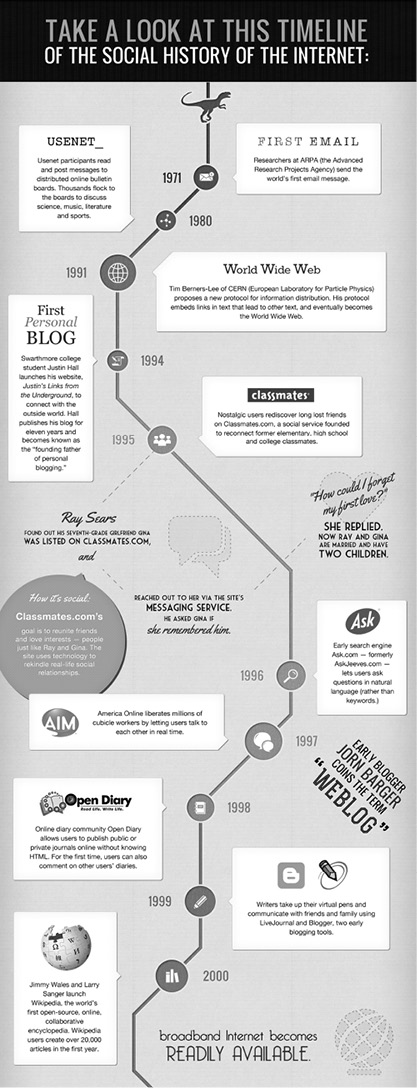

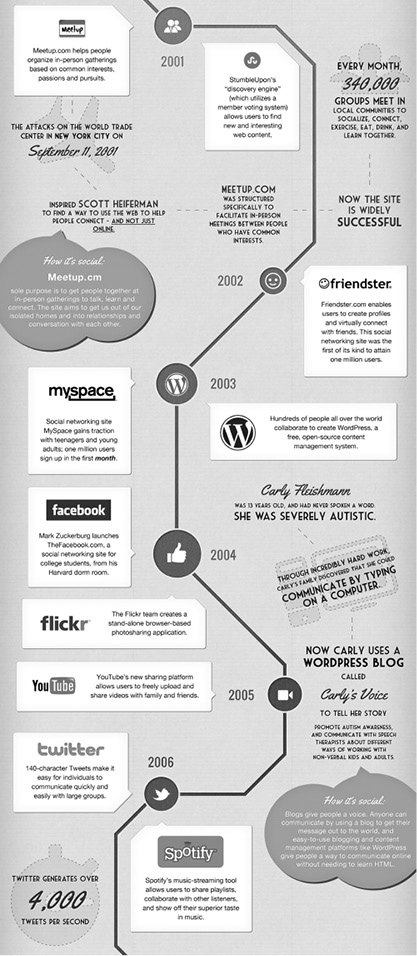

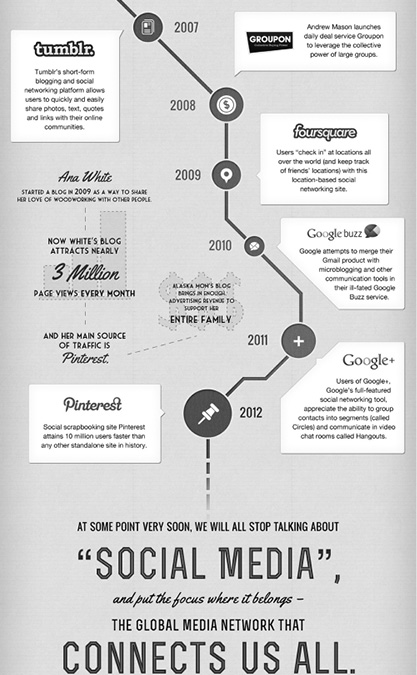

In the past, CGC platforms were users’ sources to gain information from their peers. In 1980, a platform known as Usenet, a computer network communication system, was established. This was the oldest communication system before the birth of the World Wide Web (WWW). Usenet works fairly similarly with the current social media platforms, just on a smaller scale. For example, when a user posts an article, it is initially available on his or her news server. This news server will then talk to one or more servers and exchange articles with them. On Usenet, it is normally the sender rather than the receiver who initiates the transfer. These articles were treated as bulletin boards known as “newsgroups.” On these newsgroups, only text was displayed. Unlike the sophisticated platforms nowadays with videos and photos, Usenet contained discussions based solely on the text that was shared. Many Usenet users would argue that it was the only genuine “space” people could publicly share information with unclear ownership. One of the best aspects of Usenet was that it was the only platform that “encouraged thoughtful, long-form writing with lots of quotation and back-and-forth” (www.pcmag.com). Social media has evolved over time and what used to be the trend is now outshined by new social media platforms. Figure 1.1 shows the timeline of the various consumer-generated platforms in social media.

Before discussing the motivation behind consumers’ consumption, participation, and production of CGC, we will first define the meaning of “consumer,” “content,” and “e-commerce” in the online marketing context.

Figure 1.1 The timeline of social media

Source: Hayden and Tomal (2012).

Permission to use image was sought and attained from CopyBlogger.

Definition of “Consumer”

The term “consumer” refers to the primarily consumers themselves—anyone other than professional writers, journalists, and publishers. The communication messages posted by CGC consumers are often anonymous (Campbell et al. 2011), whereas word-of-mouth (WOM) communicators are often “known to each other or at least identifiable” (p. 89). Stern (1994) defines WOM as the “utterances that are personally motivated, spontaneous, ephemeral, and informal in structure—and are not paid by sponsors” (p. 89). Nonetheless, there has still been a debate over whether WOM is more reliable than CGC. Skeptics argue that rational consumers doubt the credibility of the anonymous comments on CGC and still value online WOM (Mayzlin 2006). Campbell et al. (2011) argued that though CGC and eWOM have similar traits, communication of these two forms still differs in certain ways. On the other hand, Wang and Rodgers (2010) view eWOM as a type of online advertising that uses CGC platforms. They argue that eWOM is a specific type of CGC that is a critical component of marketing as consumer-generated reviews are regarded as more credible and less biased (Keller 2007).

Lastowka (2007) defined “user” as a dichotomy between “those who make things and those who use them” (p. 899). When the term CGC is used in the consumer market, a “user” is often aligned with other possible connotations such as consumers, purchasers, and audiences. Thus, in order to have a consumer produce CGC, there should be technology. In other words, the term CGC implies that there is an existence of two parties (producers and consumers) and two things (communication tools and content). In the context of this digitalized consumer market, the two parties will be the CGC producers and CGC consumers and the two possible artifacts will be social media platforms and product reviews.

Generally, consumers comprise the public at large. For many companies, CGC is often described as a benefit to both businesses and a type of grassroots cultural revolution. In the past, content was generated professionally, whereas now, consumers are allowed to produce their own content with available communication tools such as social media sites. The contemporary interest in CGC may not be so much in the communication tools, but in how those who produce and distribute the content can own and profit other consumers using the Internet as a distribution platform.

Web 2.0 has provided amateur content creators an innovative way to produce content at a lesser cost, along with the ability to connect with others across great distances and to engage in entertaining one another through their words. These possibilities have changed the marketing communication landscape in the consumer market. Skeptics have been critical about the benefits of CGC for society (Campbell et al. 2011; Lastowka 2007). As content is shared among fellow consumers, the information provided may be criticized as amateurish. On the other hand, some may value the information provided by fellow consumers as it appears more honest and reliable compared to those generated by companies. In addition, such CGC may be a step toward improving traditional communication models of information production and distribution.

Definition of “Content”

The word “content” in CGC is used to describe relevant and valuable information that can be presented to an audience (Lastowka 2007). In the marketing field, more specifically in content marketing, the content that is created and distributed is focused on attracting and retaining a target audience, which ultimately drives profitable customer action (contentmarketinginstitute.com). Generally, this content is the message a company or consumer uses to communicate without selling. For example, if a consumer is planning a vacation, the content is relevant to the consumer’s travel plans such as activities.

With the merging of Web 2.0 and CGC, content often comprises images, videos, or short messages posted on Instagram, YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter. Other content may also include book reviews, which may be posted on Amazon.com, and personal narratives posted on community forums and blogs. In the consumer market, consumer reviews are most significant for experiential products (Ye et al. 2011), especially when the quality of the product is unknown (Klein 1998). Litvin, Goldsmith, and Pan (2008) agreed that hospitality services are considered experiential products and are important sources of information for travelers (Pan, MacLaurin, and Crotts 2007). Furthermore, Gretzel, and Yoo (2008) recognized that travelers find reviews provided by fellow travelers are more up-to-date, enjoyable, and reliable compared to those provided by travel agencies.

According to Hayes (2015), CGCs such as photos, videos on social media, product reviews, and questions posted on the company website all play a “valuable role in creating a better shopping experience in today’s digitally-driven environment” (para 1). Further, Hayes (2015) added that the most recognized content in CGC is online product reviews. She argued that this type of content gives consumers the freedom to share their experiences and knowledge of a product. On the other hand, it gives companies an edge as it helps brands better serve their customers.

Content is not only about consumers generating valuable information as a byproduct of their activities; content can also be data generated through search engines. Lastowka (2007) argued that consumer activities such as shopping online who unintentionally generates web-surfing histories (e.g., cookies). Lastowka (2007) claim that this is a form of understanding the fundamentals of CGC. This type of content is highly significant in terms of commercial value (Lastowka 2007, p. 896).

Definition of E-Commerce

CGC generally appears on the Internet through various communication channels. Consumers are assimilating into a web-based commercial information platform known as electronic commerce (“e-commerce”) (Horrigan 2008). E-commerce activities such as online retailing and customer relationship management (CRM), have been fast growing domestically and globally and has been very competitive over the past decade (Fang et al. 2014). Transactions on this platform range from personal items to big box items such as furniture. According to the U.S. Census Bureau News (2015), sales generated from the U.S. retail e-commerce sector for the third quarter of 2015 was estimated at $81.1 billion. This is an estimated increase of 2.9 percent from the second quarter of 2015. The number of Americans who have purchased products online has also increased (pewresearch.com). Furthermore, according to GE Capital Retail Bank’s second 2013 annual report (www.retailingtoday.com), 81 percent of consumers go online to gather information before heading out to the store. In fact, the number of consumers, either researching online or buying a product or service online, has nearly doubled (Horrigan 2008).

As the online retail industry has grown and become globally competitive over the past decade (Fang et al. 2014), online vendors are constantly being challenged with customer retention (Johnson, Sivadas, and Garbarino 2008). In e-commerce, CGC “may serve as a new form of WOM for products/services or their providers” (Ye et al. 2011, p. 635). For example, Duan, Gu, and Whinston (2008) found in their study that the valence of online consumer reviews had no significant impact on the box office’s revenues. However, box office sales were significantly influenced by the volume of online reviews. In the tourism industry, however, Vermeulen and Seegers (2009) revealed that positive online reviews had an impact on the perception of hotels among their potential consumers. Regardless of whether it is the volume or valence of consumer reviews, such CGC has an impact on both the consumers and retailers (Zhu and Zhang 2006, 2010).

Within the virtual environment, several existing studies discuss influencing factors such as trust (Flanagin et al. 2014; Flavián, Guinalíu, and Gurrea 2006; Qureshi et al. 2009). This influencing factor is deemed a key predictor for customer retention because of its “crucial ability to promote risk-taking behavior in the case of uncertainty, interdependence, and fear of opportunism” (McKnight, Cummings, and Chervany 1998). However, Fang et al. (2014) realized that the impact of trust is not independent from its context. They proposed that investigating how trust operates under various different boundaries could help “specify regulative conditions” under which the effect of trust varies on online purchases (Gefen and Pavlou 2006). Practically, if firms are able to have a complete understanding of trust as a moderating effect on online purchases, they are able to “fine tune their online trust (re) production strategies” (Fang et al. 2014, p. 408).

Although trust is an essential factor for a hypercompetitive e-commerce environment, it is no longer the only triggering factor in customer’s transaction intentions (Liu and Goodhue 2012). Building a trustworthy image is no longer an option; rather it is a necessity for ongoing operations for companies that have a virtual modality for transactions. Thus, by having a good understanding of trust, online firms are able to allocate their “trust-building resources” (Fang et al. 2014) more cost effectively, thereby optimizing their return on investment by investing in trust production. A further discussion on trust is covered in Chapter 4.

The Changing Landscape of Marketing Communications

To meet the demand of a fast-paced lifestyle, the virtual world has changed its “laid-back” setting to a more complex and dynamic landscape comprising of both traditional and interactive media. Many companies that use traditional media such as TV or radio realize that they are struggling to provide an interactive environment that provides the opportunity to capitalize on this fragmented market. Companies attempt to offer their consumers a unique media channel (e.g., social media) that enables the latter to voice out among the rapid and enormous amount of information and advertisements (Daugherty et al. 2011).

Unlike mainstream traditional media such as television and radio, many consumers have moved toward an evolutionary change in lifestyle and toward the use of social media. With the abundance of “space” in the virtual world, online media has created a robust information hub for both marketers and consumers. The intention of creating this hub is to provide an efficient and timely communication channel. The challenge that companies currently face is the integration of their offerings with the lifestyle of those consumers. Anderson (2007) argued that despite the consistent growth of television viewership, television suffers from a production of program offerings that leads to fragmented audiences and a decline in program ratings. The Internet has reached a stage where it is the “go to” media outlet, above all other traditional media communication channels. According to the 2012 census bureau report, nearly 75 percent of American households use the Internet at home (www.census.gov). Furthermore, more than 78 percent of the adult population uses the Internet (www.census.gov).

Although consumers still utilize traditional media, the trends in media usage have changed drastically. Now, consumers have more control over what they want to use, hear, and see, and audiences are given the opportunity to create media content freely by themselves and not rely on traditional gatekeepers (e.g., publisher) (Perry 2002). Furthermore, research has indicated that the presence of the Internet has changed the way people communicate information. This communication process, known as WOM, is where consumers create, share, and propagate information (e.g. shopping experience) (Gupta and Harris 2010; Kozinets et al. 2010). Digitalized WOM (i.e., eWOM) is accessible 24 by 7 anywhere through diverse social media such as blogs, social networks, customer reviews, and forums, which has an impact on prospective or existing consumers (Dellarocas 2003; Schindler and Bickart 2005). It is not uncommon for a consumer to obtain information on a product from his friends or family. In addition, consumers can also expand their search effort by consulting fellow consumers’ reviews, blogs that are specifically written on a particular topic or even summarized opinions contributed by micro-bloggers. According to Nielsen’s Global Trust in Advertising Survey (2012), online consumer reviews are the second most trusted source for brand information—70 percent of global consumers attested to that claim. Earned media such as WOM or recommendations from family and friends, above all the other advertisements, was indicated as the most trustworthy source by 92 percent of the surveyed global consumers.

In the mid-1990s, companies were reliant on traditional business practices—marketing communication controlled by distinct and identifiable corporate spokespersons (Hoffman and Novak 1996). However, current marketing practices are “evolving into true participatory conversations” (Muñiz and Schau 2011, p. 209). Unlike in the past, marketing communications have transformed into two-way, many-to-many, multi-modal communications. The impetus behind this dramatic change and the context in which these conversations are taking place is known as the Internet. Methods of marketing communication have been forced to adapt with the advent of the Internet and social media, for example, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube (Dev, Buschman, and Bowen 2010). According to Muñiz and Schau (2011), conversations are related to brands and products within brand sites. There have been various names given to all these different brand sites and this is all part of the creation and exchange of CGC (Chu and Kim 2011). These sites include special interest groups and blogs (e.g., review forums), community forums (e.g., Starbucks), collaborative websites (e.g., Wikipedia), microblogging sites (e.g., Twitter), social networking sites (e.g., Facebook), customer reviews (e.g., Yelp, Epinions, Amazon.com), and video mash-ups or better known as creativity works-sharing sites (e.g., YouTube). All these market-oriented conversations are nothing like the corporate-driven, calculated, and coordinated communications. All these types of CGC “disseminate multi-vocal marketing messages and meanings” (Berthon et al. 2007).

Since the introduction of the Internet, consumers have transformed from passive bystanders to hunters (Hanna, Rohm, and Crittenden 2011). Passive bystanders refers to consumers that are not in a dialogue with the advertisements that are created through traditional media. Whereas, hunters refer to consumers who are able to control the content and are in fact in a dialogue with the company’s Internet-based marketing campaigns. Consumers now make their own content and propagate it on social media sites such as YouTube. As Campbell et al. (2011) asserted, “the creation of advertisings and brand-focused videos is no longer prerogative of the organization or its designated ad agency” (p. 87). When CGC is in the form of advertising, consumers create brand-focused messages with the intention to inform, persuade, and remind others (Berthon, Pitt, and Campbell 2008). CGC has the ability to influence consumers’ perception toward a brand, destination, and company (Campbell et al. 2011; Lim, Chung, and Weaver 2012; Ye et al. 2011). Duan, Gu, and Whinston (2008) demonstrated in their study that online consumer-generated reviews have a significant influence on sales of consumer products.

In the tourism context, Lim, Chung, and Weaver (2012) found that destination-marketing organizations have incorporated branding techniques with social media. Furthermore, consumers are gradually leaning toward the use of various social media for CGC to give them more information (Yoo and Gretzel 2011). Social media has become a powerful communication tool for consumers to share their experience, which in turn influences their decision-making process. CGC does not comprise just written reviews; it can also be in media and advertising forms. Litvin, Goldsmith, and Pan (2008) added that consumer-generated media websites have grown to be one of the prominent platforms in improving information accessibility and for enhancing consumers’ decision-making processes. Ayeh (2015) pointed out that there is a growing interest in consumer-generated media and social media in general, but not all consumers are convinced about the use of consumer-generated media in their decision-making process (Burgess et al. 2011). This is probably because CGC “poses a challenge when it is in the form of advertising” (Campbell et al. 2011, p. 87).

Consumers’ Role as Co-Creators in CGC

The idea of consumers as co-producers or co-creators is not novel in the marketing field. Theoretical models have been developed in this idea within the B2C relationship research area—one of which is the widely applied service-dominant logic (S-D logic). Vargo and Lusch (2004) argued that from the traditional, goods-based, manufacturing perspective, “the producer and consumer are usually viewed as ideally separated in order to enable maximum manufacturing efficiency” (p. 11). Based on their S-D logic model, they argue that from a service-centered perspective, the consumer is always involved in the production of value. However, they noted that for these services to be delivered, customers are still required to have the knowledge to use and adapt. Essentially, the development of this model indicates that the role of consumers is not just “target”; rather they are an operant resource (co-producer) in the entire value and service chain. Yi and Gong (2013) developed a customer value co-creation behavior scale to measure two elements of customers’ co-creation behavior. These two elements are: customer participation behavior and customer citizenship. The former measures consumers’ information-seeking, information-sharing, responsible behavior and personal interaction, whereas the latter focuses on feedback, advocacy, helping, and tolerance (p. 1279).

S-D logic, although heavily applied in the service context, is often used by marketing practitioners toward engaging their consumers with their product and service development. One way in which these consumers are involved in value creation is through their contribution of information on blogs, websites, review site, and on any social media platforms such as Facebook. For example, Doritos is one company that encourages their existing customers to co-create new products.

Humphreys and Grayson (2008) argued that co-creation for use and co-creation for value exchange (for others) should be distinguished. The difference between these two processes lies in their orientation. Co-creation for use is performed by a specific consumer for his or her own benefit, whereas co-creation for others is to benefit other consumers. Witell et al. (2011) claim that the aim of co-creation for use is to enjoy the production process and its outcome, whereas co-creation for others is to provide an idea, share knowledge, or participate in the development of a product or service that can be of value for other consumers.

Witell et al. (2011) argued that consumers play an important role in the production process. Furthermore, they posit that an organization must learn to develop its collaborative competence to move away from the perception that consumers are a source of information, and toward treating the consumer as an “active contributor with knowledge and skills” (p. 9). Companies not only need to engage consumers in the collaborative, participative, and contributive process; they also need these consumers to distribute the content forward. Hence, the term social curation (Villi, Moisander, and Joy 2012). Social curation is the next generation of collaborative effort where consumers become part of a company’s marketing strategy.