7. Select Killer Work for Your Book

Choosing projects that reveal your skills, talents, and passions.

Your portfolio is an organic, fluid, and evolving representation of your work and personal brand. The projects you create for your book of work, the examples you include, and the way you present them all communicate your creativity, skills, range, thinking ability, and ambition. Your portfolio is the single most important vehicle you have for finding employment. It needs to be nurtured and updated frequently to reflect your evolving skills and experience. However prestigious the design school you attended, without a strong portfolio, no one will ever see or understand what you have to offer.

Selecting the right projects, arranging them logically, and presenting them in a way that is unique and engaging takes forethought and planning, and when you’re just starting out, predicting what will captivate your audience most effectively can be difficult. This is when the value of understanding your personal brand becomes clear; it takes the guesswork out of your decision making. If you’re unsure about something, you can weigh your options against the framework of your creative brief. My design assistant Margaret (from Chapter 4) perfectly meshed her two passions, donuts and henna art, to provide a feast for the eyes that entices viewers to learn more about her work (and to crave a sweet treat). When the pieces you select are true to your brand, you can be confident that you are making good choices. And, when your decisions are validated by an invitation to interview for a job, you’ll feel like you’ve won an Academy Award.

In the meantime, no matter where you want to go, you need a well-thought-out portfolio to get you there.

The Purpose of Your Portfolio

Your portfolio’s main purpose is to promote your work and your brand. You can use it for a multitude of functions, such as finding full- or part-time work, networking to get an adjunct teaching position, scoring freelance projects, or selling branded goods directly to customers. Before you build your portfolio, you should identify your primary purpose at this moment in time (understanding that it may change in the future) so you can select the appropriate projects and present them in the best possible way. Need some extra motivation? Your portfolio has the power to generate revenue so you can pay back student loans more quickly, establish a retirement fund earlier, or splurge on a vacation to somewhere that refreshes your creative spirit.

Employment. Finding a job is the most frequently intended use for a portfolio. Do you want to work for an in-house design team, a large advertising agency, or a UI/UX design firm? Think about projects you have completed that are relevant to the industry, type of company, job position, and size of the organization where you want to work. When your “ideal” employer sees that you have at least some experience, familiarity, or the desire to do what they need done, you’re likely to make the short list of people who get called for an interview. Your portfolio provides necessary insight about your personality, giving your employer an idea of your work style and how you might interact with others in your shared workspace.

Freelance. The popularity and widespread acceptance of personal websites (your own) and portfolio websites (such as Behance and Coroflot) can offer fledgling designers an unprecedented opportunity to promote their expertise and make their availability known to potential buyers. Freelancing has its pros and cons (especially if you’re simultaneously holding down a full-time job—more about that in Section Three), but it offers virtually limitless potential for making money and building your portfolio, whether you’re looking for traditional employment or not. Freelancing can pay bills when you’re revving up to strike out on your own or filling the income gap between gigs.

Network. Just as I took control of my romantic destiny in Chapter 4 by asking friends, family, and colleagues to help me find love, you have to seize control of your professional future by networking. If you’re going to end up where you want to be, you need to spread the word about your talent. Make connections with other designers who can give you job referrals. Ask someone to invite you to Dribbble (a show-and-tell website for designers) so you can solicit feedback on your current projects and works in progress. Identify where the people you want to work for tend to congregate (online or in person), and then show up and introduce yourself. (Gentle and professional stalking is generally permitted.) Actively seek out new venues for promoting yourself wherever you happen to be gaining experience or getting educated. Regardless of where or who you choose to schmooze, make your portfolio available to everyone you can because your contacts, as well as the people they network with, are likely to spread the word that you are good and that you are available.

Commerce. You may be an excellent illustrator, product designer, or design entrepreneur, and that means you may have a product you can sell directly to someone who needs it. While you’re creating your personal brand and the brands or campaigns in your portfolio, you could come up with some good ideas that are commercially viable. RBSD industrial designer Dominic Cullari’s love of watches inspired him to design a line of elegant unisex wearable timepieces (domenicompany.com). His colleague, Alex Lorenca, designed a line of wallets made of wood. I purchased three of them, which were quickly scooped up by my son Dylan to use for storing his Pokémon cards.

The pathways to making money from your talents are many, and it’s easier now than it’s ever been to sell stuff online using e-commerce websites thatproduce, ship, and market your wares to a global audience. If you’re looking to create your own line of clothing, wallets, or other goods, these websites may support your selling efforts and help you generate some income right now: Print Aura (printaura.com), Big Cartel (bigcartel.com), and Etsy (etsy.com). I have been encouraging the donut-obsessed Margaret to take her henna drawing talents to yet another level—designing a line of furniture that she can sell. When it comes to selling products online, the potential opportunities are limitless.

What to Include in Your Portfolio

There is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all portfolio, so you have to figure out what’s right for you. In addition to the framework of your personal brand and creative brief, the guidelines in this chapter (including the tools I mention at the end) will help you identify and qualify samples that will dazzle whoever looks at your book, as well as give them a clear idea of who you are and what you can do. The projects you include should reflect what you want to do and give your audience insight into your interests. If you are already a practicing professional, don’t show work that is more than five years old, unless it was a significant project. This type of project works best as a case study.

Work that reflects what you want to do

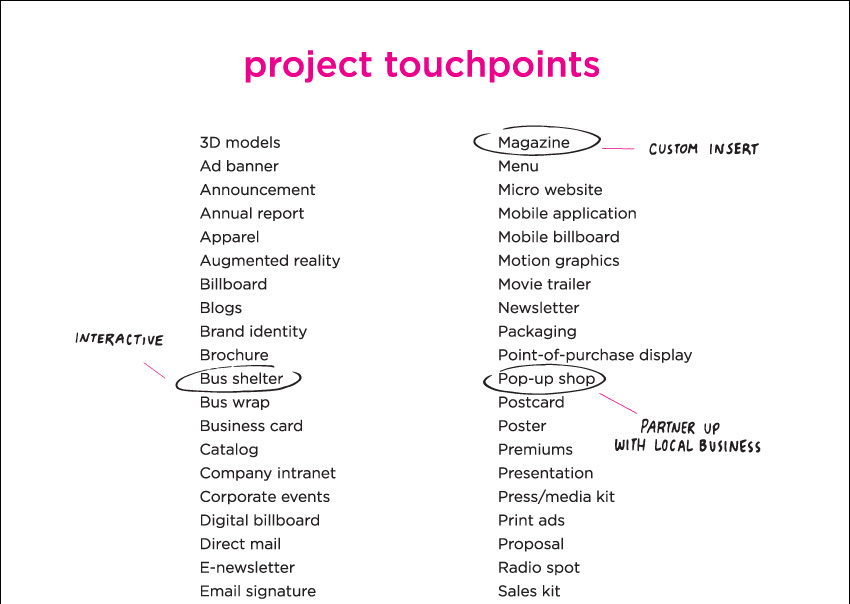

The projects in your portfolio should show off your best and most original ideas, and they must be well executed. Showcase the work that you love and the type of work that you’d like to be hired to produce. Anything you include should demonstrate your skills, abilities, range, talents, and experience. For example, if you want to be an art director at a large metropolitan advertising agency, integrated promotional campaigns will highlight your ability to tell a single story across multiple print and screen touchpoints. If you want to work as a graphic designer in a small, local agency, a more diversified book that includes identities, packaging, websites, and mobile designs will demonstrate your range.

Whether you use work created in the classroom or actual professional projects, the pieces you select should resonate with your audience, be relevant to your desired industry and company, and reflect the role you’d like to fill. The more your portfolio targets the real needs of a company, the more attractive you’ll be as a potential hire. Remember, you don’t get extra points for quantity, and including too much can actually work against you. Choose wisely, and save a few items (such as illustrations, a series of book covers, personal projects, or smaller brands that don’t need to tell a big story) to display only on your website, where you can use them to complement your portfolio pieces.

Work that reveals your interests

As I mentioned in Chapter 6, personal or passion projects reveal something intimate about who you are and how you think. Any designer vying for a position in a top company may have a great portfolio, but no professor or art director can teach a designer to self-ignite and be inspired on their own time. Your portfolio can make that clear before an employer has to ask. Well-known designers Jessica Hische and Jessica Walsh are great examples; they both used passion projects to communicate that they consider design a way of life. By promoting the things they love, they attracted recognition far beyond the design industry. Their success came from effectively communicating a deeper understanding of what they care about (drop caps) and connecting to others through experiences that were deeply personal (dating).

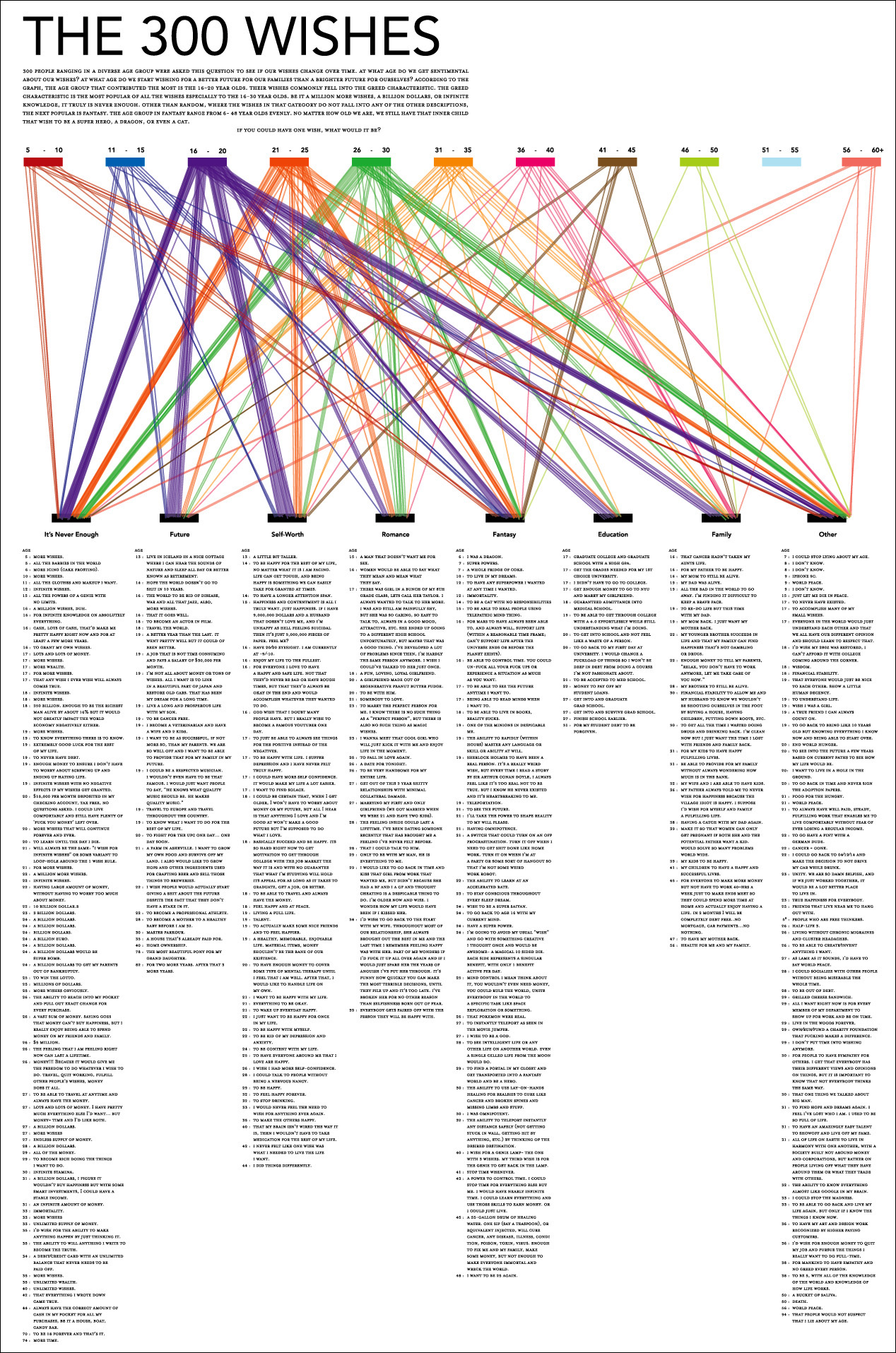

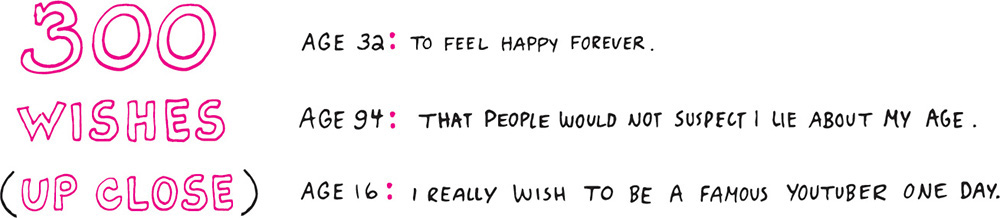

Passion projects often connect to the viewer more quickly and dynamically because they are memorable. Advertising major and illustrator Ria Venturina designed a poster for a personal project she initiated before completing a course. Via social media channels, she asked 300 random people from diverse age groups, “If you could have one wish, what would it be?” (riaventurina.com/assets/300wish.pdf).

Graphic design major Jaime Mazauskas conceptualized a business idea for a bar crawl event that coincided with WrestleMania (jaimemazauskas.com/maniacrawl.html). Both students were passionate about their topics; their enthusiasm for their projects and their ambition to go beyond what’s typical invited and inspired lively conversations about their concepts, progress, and outcomes.

Including self-initiated projects in your portfolio will give a potential employer greater insight to your thinking abilities and ambition. What inspires you? What are you passionate about? Include at least one personal project in your book and make sure the work is of the same caliber as your other projects—engaging, organized, and well-executed. Your personal project captures and reflects your pixie dust; it can help you stand out from your competitors.

How to Select Work for Your Portfolio

Now that you know the types of projects your portfolio should include, you must evaluate and qualify the specific samples that will populate your book of work. Even though you’ll include individual projects that represent your range of capabilities, your overall presentation should still have a theme. My former student Kaila Edmondson’s “Femme Forms?” uses a classic dress pattern and female body parts to express a clear idea about female body image, a theme that ran through her entire portfolio. Selecting (and setting aside, at least for now) work samples is challenging no matter how long you’ve been practicing design. When you’re starting out, you probably won’t have all the projects you need for your dream job or that job posting that looks interesting to you. That’s to be expected, and it’s okay. Based on what you’ve already produced, the following guidelines will help you identify which pieces need further development or refinement, what you need to start (or restart) from scratch, and which items you might want to leave out. As always, don’t try to go it alone—solicit feedback from your professors, mentors, colleagues, and other design professionals. They’ll help you qualify whether the projects you select are portfolio-worthy and, if they are, offer some guidance on how to improve them.

Tell good stories

“Project” stories. Just like your personal brand story, the stories you create for your individual brands and campaigns must be authentic, rich, credible, and composed of details about what makes them unique. To qualify for your portfolio and intrigue an art director, each campaign must visually and verbally communicate a story that is “smart” (believable) and “with heart” (emotionally intelligent). Your audience will appreciate the effort that your story reveals and the outcome—quality work. Some of my job-hunting students have been told that their brands are so “real,” they could go to market with them. I love hearing this. It means that their stories are compelling and credible. It tells me that they have learned how to connect to their audience. Be prepared to say something interesting about any of the images you’ve included in your book, but remember you may not need to say anything at all if your viewer’s style is to appreciate the work on its own merit.

“Process” stories. You’ll usually find that one of your projects was more challenging or fun to work on and the outcome more satisfying than others. Identify that project and build a case study around it. Learning about a project’s back story allows your viewer to better understand the concept, design direction, or process that made it successful. Remember to include the requirements outlined in the project brief, any challenges or obstacles you had to overcome, and how the solution (technical, design-thinking) communicates your problem-solving abilities. If it’s a professional project, do you have metrics to support its success? Do you have client testimonials to praise your efforts and endorse your results?

Always make sure your story is believable; do not exaggerate, invent facts, or make it any longer than it needs to be. When you give people a reason to care about each case study, they’ll keep reading. Include details about how you created a particular icon or a repeating tiled background. Write about how each idea came into being and why it was rejected or accepted.

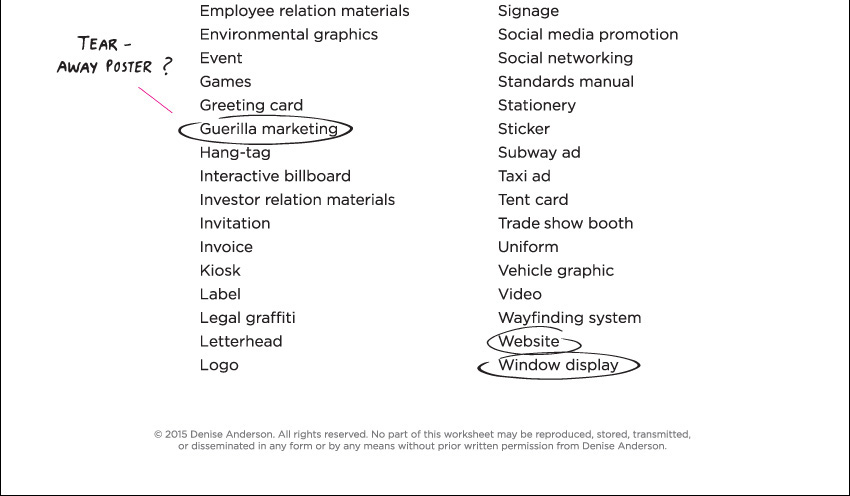

Diversify product types and include a range of touchpoints

One thing I love about living in a city is the confluence of many things, not the least of which are food choices. On any given day, I can stop at a French bakery to pick up my decaf Americano and a baguette. (Sometimes, it’s an Escargot a La Cannelle—a cinnamon swirl pastry—because they look so irresistibly scrumptious.) Then, I can walk a few doors down and buy some Japanese rice balls with Indian curry for lunch. Across the street, I purchase freshly made marinara and raviolis for dinner. In a matter of 15 minutes, I can tour three countries and relish three different sensory experiences—the lingering aroma of butter and warm yeast wafting through the bakery; the firm, smooth texture of the seaweed paper that encircles the rice balls; and the fading yet evocative posters and thickly accented English that send me right back to my visits to Italy.

Selecting work for your portfolio is a lot like the food tour we just took together. My city and its food choices are the brands and campaigns you have created. The eateries we visited are the touchpoints that your viewers will experience as you guide them through the sights, smells, textures, and feeling of each project. Your portfolio should offer the viewer a diversity of experience; each piece should tell them something about who you are and what you love to do.

Let’s say you want to work in a firm that creates brand identities. To engage your audience, include a range of identity and client types (rebranding, retail, not-for-profit, corporate). Each should show a mix-and-match of cross-platform touchpoints (print and screen). Variety is important, because it demonstrates you can approach projects in different ways, and employers like to see your versatility and agility with a range of platforms. If you are applying for a specialized position (website design, for example), you should still show some variety rather than limiting yourself to three replicas of three similar company and client types.

You may want to consider having more than one portfolio to choose from. This will allow you to tailor the strengths you promote to meet the needs of the person who may want to hire you. Remember, your book is fluid and ever changing; you will swap out, mix-and-match, and update pieces according to the opportunity you’re pursuing.

Communicate wicked skills

The work you choose to showcase in your portfolio should communicate the skills you can offer. The more skills you reveal, the more marketable you’ll become to a prospective employer. For example, if you want to build websites or mobile apps, you can stand out by showing off your technical abilities and code your online touchpoints. But don’t leave out the other creative talents you can offer. For instance, if you are a good photographer or illustrator, include and make note of any images you created for your projects. My former student Triana Braxton (trianabraxton.com) promoted her skills by blending them into a single digital portfolio. Her ability to promote herself through her skill set landed her an in-house job for a national health club chain immediately after graduation. When you consolidate your individual talents together into a bigger overall presentation, such as your portfolio website, you effectively advertise what you can do for an employer.

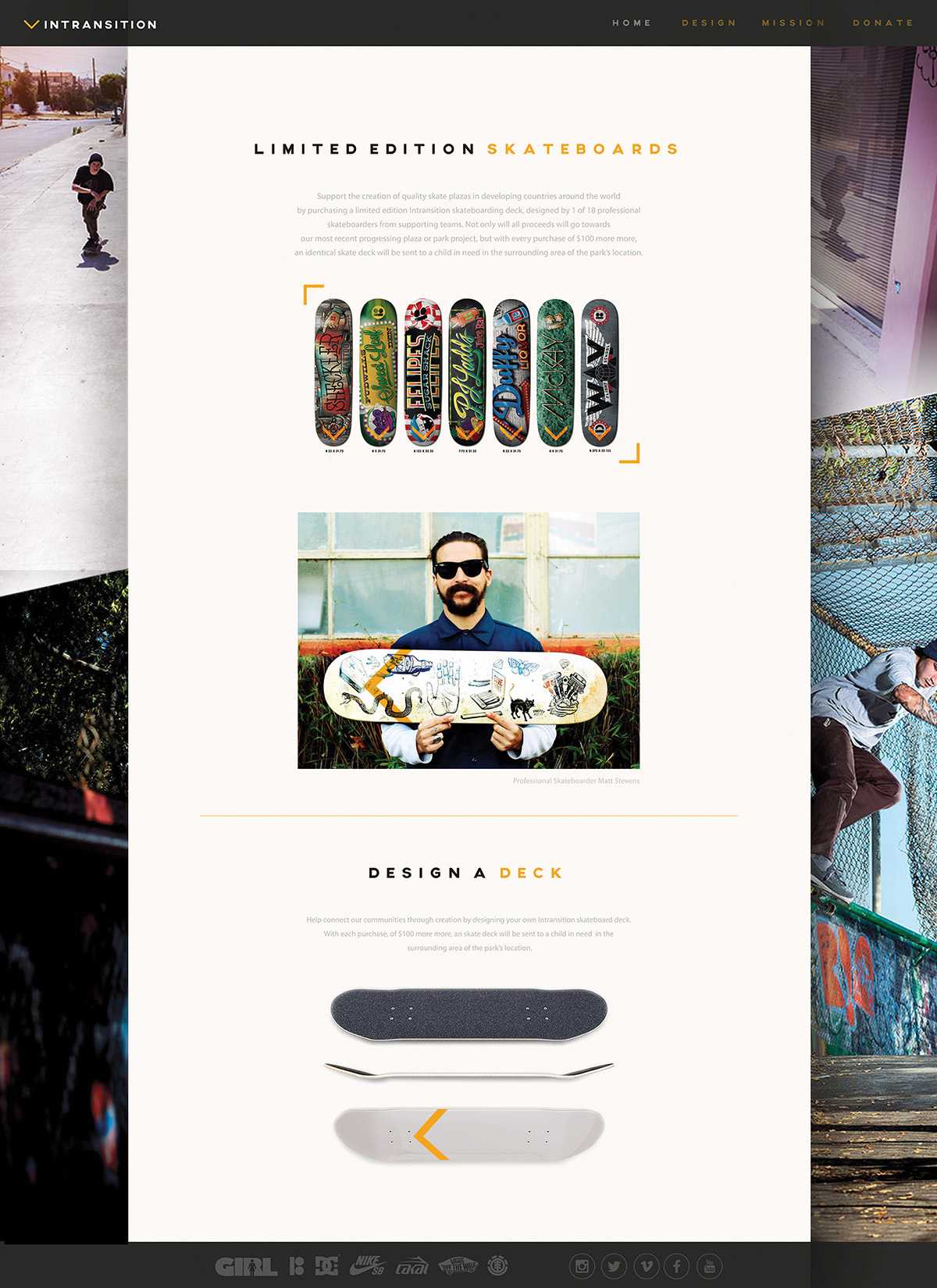

Also, consider any skills you have that fall outside of design. (Your “inside self” Personal Brand Self-Assessment Study in Chapter 1 has this information.) My former student and illustrator Max Friedman has been skateboarding since he was a kid. Mike DeBisco, also one of my former students, has been a disc jockey since high school. Like Max and Mike, you may have skills that seem unconnected to your design talents but can be used to paint a fuller, more detailed picture of who you are. And better yet, those skills may be the factor that connects you to a real job, because a potential employer sees how you fit into their company culture. Your outside skills can even offer you an advantage over other candidates: maybe the company just snagged a large skateboarding client and can use your expertise on the account, or the art director has a regular Saturday night gig spinning tunes at a nearby nightclub. You never know who’s looking at your portfolio or what their outside interests are, so it’s better to include what’s interesting about you than to leave it out and miss an opportunity to get their attention.

Art directors and hiring agents look for designers with skills that go beyond design. So think critically and seek out the nuances that nudge you past the competition. Find ways to visually or verbally show off your wicked and individual talents and skills, and weave your personal brand story into your overall portfolio of work. You may need to highlight your story as a case study or list your accomplishments in a credit roll. Regardless of what your individual talents are, communicating with passion about your talents will be perceived as a skill in and of itself.

Choose the right number of pieces

I once asked my father-in-law Tony how much garlic it takes to get his sauce to be so tasty. “Just enough so you always want to take one more bite,” he answered.

How many projects should a design portfolio include? How many do you need to tell your overall brand story? You may find my answer frustrating: it depends. Only you know what it takes to communicate your brand and provide a sampling of what you can do. The answer will vary from function to function and audience to audience. Are you presenting an online, digital, or print portfolio? What are the expectations in the industry where you seek employment? Many art directors estimate that a portfolio should include no more than 15 to 20 pieces total. (Some say less; others more—see what I mean?) At the RBSD, we recommend that Interactive Advertising and Graphic Design majors present four to five integrated brand campaigns (18 to 24 pieces) with four to five pieces per brand. Photographers and illustrators may show 12 to 15 pieces of their best work and then send the viewer to their website for more.

As I’ve said before, art directors are busy, and they need to quickly assess your body of work to find out what you want, what you can do, and how your offering fits with their needs. They don’t have time to waste, so filter the projects you include in your portfolio to display only the strongest, most cohesive work. Think of it this way: your portfolio will be judged not by your best work but by your worst piece. Choose quality over quantity. There is no “correct” number when it comes to your portfolio pieces (or garlic); you just need your viewer to crave another bite.

The project worksheet is my students’ most helpful tool for planning and selecting work to populate their portfolios. I consider it a contract between the student and me, and I use it to track their progress throughout the semester. The following is an example and bullet points on how to use it. Create your own version or modify my worksheet for your projects.

The project calendar works in tandem with the project worksheet to help students schedule the design and production of their projects, in addition to developing discipline and strengthening their organizational skills. To use it, start at your deadline and, working backward, establish due dates for developing the components of your projects. While writing and designing this book, I used a similar calendar, and it was immensely helpful. (It’s also helpful to have an editor who keeps tabs on my deliverables and progress, just as your professor and/or mentor will monitor your progress.)