13. Prepare for Your Presentation

Initiating a conversation about your projects that reveals your story.

Everyone loves a good story, and the most memorable stories are interesting, believable, and emotionally evocative. At this point in the process, you’ve created a portfolio that is a visual narrative of your creativity, skills, range, design-thinking ability, and ambition. You’ve developed touchpoints for engaging your audience in a series of signature and smaller (but meaningful) interactions. Now, when you’re called upon to present your portfolio in an interview, you have to become your story’s living, breathing narrator and your brand’s most enthusiastic advocate. It’s time to paint a rich and accurate picture of who you are. The story of your portfolio is the soul and spirit that drives your projects.

When I think about the student projects I’ve reviewed over the years, the pieces that continue to live in my memory are connected to stories that speak to my values (Alexa Mato’s “Adelino Butcher and Wine” identity); tickle my appreciation for wit and humor (Max Friedman’s “Blue Peters” craft beer illustrations); or tap into my business side (Jefferson Saldeno’s “Dual” soda packaging from Chapter 8). I remember the designers because their stories resonated with me on a deep emotional level. Alexa created her brand to honor her grandfather, Adelino who owned a butcher shop in Portugal. Max introduced his sense of humor through his drawings. Jefferson conveyed his excitement about a new product idea through his expert 3D rendering skills. The students’ projects demonstrated the quality of work they are capable of producing, but understanding how each turned a simple class assignment into a personal quest revealed to me who they are.

Connecting to an interviewer by sharing a behind-the-scenes glimpse of your process, your personal journey, and your approach to design is key to getting hired. Your portfolio may be exceptional, but employers don’t hire your portfolio; they hire you.

How to Tell Effective Stories About Your Projects

With the right approach, the story behind your work can be as compelling as the design itself, but presentation skills don’t come easily to everyone. If you’re uncomfortable talking about your work or giving presentations in general, you must develop the ability, because talking about your portfolio is critical to selling your ideas and finding a job.

Presenting your portfolio is simply having a conversation with someone about your projects. Your objective is to (humbly, but proudly) tell the real stories behind the work and how you created it. As you begin to do this, you will find yourself becoming actively engaged in the conversation you’ve started, because there is no better expert on your process, your perspective, and your experience than you.

Using a combination of spoken words and visual images, your objective during the presentation is to precisely and clearly tell the viewer about the problem and then show them how you solved it.

Highlight the information your reader needs, and focus on the points of the project that make it interesting and exciting. Weave stories about your work into the overall narrative of your presentation. Like a fisherman patiently dangling tasty-looking bait to entice a fish, you want to keep your viewers enthralled and drawing ever closer until, with your last and best project, you “hook” them into a story that’s particularly memorable and compelling.

You won’t be able to hook everyone you meet with, but each time you cast your line, you learn something you can use the next time. You refine the details of your stories. You focus less on what your touchpoints look like and more on how they connect to your audience. You leave out one story and add another. You continue to improve your content and perfect your delivery.

As you gain experience, you’ll get better at reading your audience and knowing when and how to change gears if something isn’t working. In the meantime, I don’t recommend winging your presentation, even if you are a natural performer. What you say about each project should be intentional and practiced. Keep your stories short and succinct—all you need is two to three minutes per project—because anything longer can come across as rambling, and anything shorter may seem rushed and unprepared. Show humor, humanity, and authenticity. Be confident, clear, and compassionate. Practice in advance so you can muster up the confidence and energy needed to be your wonderful self.

Start with the problem. Graphic designers solve problems. Interviewers want to know how you did it. When you’re telling a story about your work, start by giving your audience the context or background of the project. Your viewer will better understand how you used your design-thinking abilities and skills if he or she understands the problem that you had to solve. Neglecting to mention the challenge you faced at the outset is like starting a conversation in the middle; it’s confusing for the person at the other end and frustrating for you when he doesn’t understand. When you build your stories purposefully, you create excitement and anticipation for what comes next.

Use the creative brief. When you’re preparing to talk about your work in terms of its context and the problem you solved, your best resource is the creative brief. Summarizing a project’s strategic objectives and needs, the creative brief outlines the purpose, target market, brand attributes, unique selling proposition, and anticipated outcomes that will be used to determine whether the project is successful. (All of the projects in your portfolio should have been initiated with a creative brief. You can make use of them again to recall and highlight the most relevant project details.) This background information becomes the framework for talking about the solutions developed. For example, if you rebranded a business, you can share why the company needed the update: “The company was launching a new product line,” or “The next generation of the family wanted to go national.” State the problem that needed to be solved as simply as possible, preferably in one short sentence.

“It’s not that I am smart; it’s that I stay with problems longer.”

–ALBERT EINSTEIN

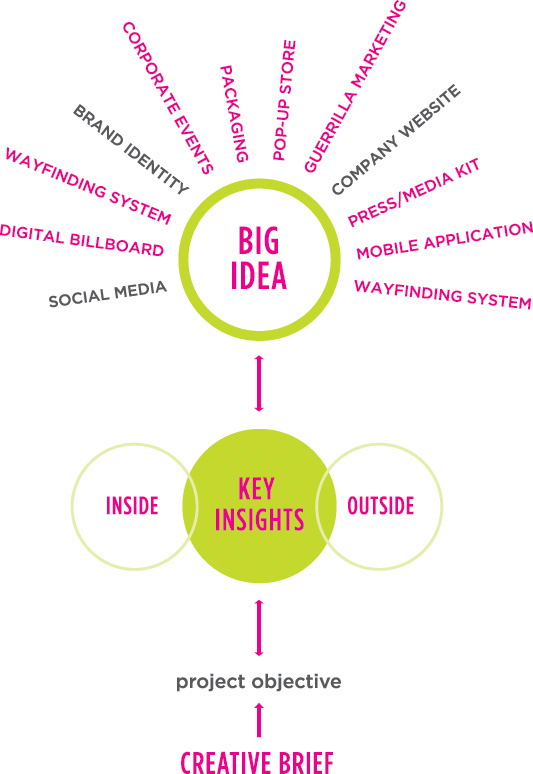

Share your research insights. The creative brief provides a context for the project, but before you could solve the problem, you had to do some research and gain additional insights. When you’re putting your presentation together, spend some time reviewing your research notes and analyzing what you learned that the creative brief didn’t tell you. When you’re presenting, talk about those key insights from your research that helped you refine your understanding of the problem and steered you to your solution. Discuss how your discoveries shaped your strategy and led you to the “big idea” of the project.

When I’m working on a problem myself, I think about an Albert Einstein quote I cut out of a newspaper years ago: “It’s not that I am smart; it’s that I stay with problems longer.” When you can articulate your understanding of the problem, talk about your research and the insights you gained, and discuss how it all led you to a solution, you demonstrate to your interviewer that you know how to stick with a problem until you get to the heart of it.

Reveal your “big idea.” Your big idea connects the problem to your solution and your solution to the target audience. How did you solve the problem you’ve just described? Why did you solve it that way? How did you communicate your message to the end user? How did you use your insights to create an engaging experience? Share your “aha!” moment with the interviewer, and engage her in your process.

Every time I assign a project, I marvel at how many different solutions can spring from a single problem. Everyone in the room brings a unique combination of life experiences, education, and skills that lead to designing something that no one else can. When my student Marc Rosario (who lived in the Philippines as a child) wanted to re-brand a Filipino food product in the United States, his firsthand knowledge of both cultures was instrumental to his developing a design solution for the American market. Every design problem can be solved in many ways, but your interviewer wants to know how you solved it and why you chose that direction. What concepts did you explore? How did you distinguish the great ideas from the good? Explain the big idea of your project so you can emotionally connect your audience to the touchpoints you’ve created.

Let’s say, for example, you received a creative brief that introduces a manufacturing company that is undergoing a major expansion but losing skilled technicians who are aging out of the workforce. The creative brief outlines the client’s urgent need to recruit and train graduating high school students and military service members, to educate them about the long-term benefits of a manufacturing career, and to encourage them to enroll in a specialized training program that the client offers to new hires. In your research, you notice that the company still employs an elderly woman who’s worked there for over 60 years, so you interview her and find out that her father spent his entire career with the company, too. This gem of a discovery inspired your big idea, a “Many Generations” campaign that the company used to recruit and train skilled technicians to meet growing demand.

Explain the touchpoints. Your touchpoints communicate, strengthen, and support the big idea of your project; they are the vehicles your viewer uses to experience the brand. After you introduce the big idea, talk about why you chose to use those touchpoints and describe their relevance. Lead with the most significant piece. For example, when my former student Stephen Sepulveda developed the presentation for his “Views and Brews” project, he focused first on a mobile app that he designed to serve as the primary interaction between the company (a new business idea combining craft beer and hiking) and the end user (a craft beer-drinking hiking enthusiast). His app included real content—consistent messaging that supported his idea and relevant visuals to engage the viewer. His prototype made the viewing experience believable and clearly displayed his technical ability. He followed up by discussing the other pieces he had created to support the brand and how they also supported his big idea.

When you’ve described how the primary touchpoint connects to your big idea, you can move on to discuss how you selected the supporting pieces that reinforce that main touchpoint and the overall project idea. Why did you use illustration instead of photography?

Why do you think these two typefaces complement each other and speak to the audience? What elements of the website layout carried over to the magazine design? When you’re asked how you did something, be prepared to talk about it and show your sketches, false starts, and prototypes. Point out any content in your pieces that you created, such as the illustrations you made, photos you shot, or anything else you produced to create, support, or enhance your idea. Every element and phase of your design process is another component of how you solved the problem and how you demonstrated the skills, technical acuity, and craftsmanship to execute it. The more you prove what you can do in an interview to separate yourself from competing candidates, the more likely you are to stand out to a prospective employer.

My RBSD colleague and Kean graduate Jim Burns, who is now vice president of product design and development at EastPoint Sports, tells the story of how he received similar advice on one of his first interviews, wise words that have served him throughout his career. “You have a beautiful and well-structured portfolio,” the interviewer told him. “But here’s the thing to remember: when I look through your book, it has to be so good that I want to run down the hallway and show it to someone else. If I don’t react that way, then you’ve missed the mark.” She offered Jim a job in Grey’s design “bullpen,” but cautioned him against getting trapped and urged him to rethink his portfolio. “Show some sketches. Show your design-thinking,” she said.

Jim didn’t take the job, but he took her advice to heart, and today he encourages his students to tuck away a few folders of sketches and references on how they came to their prized and featured projects. “If someone asks you about how you solved the problem or came up with an idea, you can show them how you got to the solution,” he says. “It’s what I look for in the people I hire.”

Share the credit. If you had a significant role in a collaborative project, give credit to the team and be specific about your contribution to bringing the project to fruition—maybe you designed the brand identity or coded the website using your HTML and CSS technology skills. A hiring agent may see the same project in more than one portfolio, so don’t wait until you are asked to mention that you were part of a team. Talk about the value of the collaboration and how the contributors strengthened the overall project idea and its final execution. Working as part of a team is a valuable skill that employers look for in their employees; if you have any team experience, share it.

Prepare and practice. An art director wants to know the journey of how you came to the work, as much as or more than how the projects turned out. When you learn how to communicate or “tell your story,” you can demonstrate what you can do and how you can do it. The only way to pull this off effectively is to be prepared with a script and practice until you can speak about it like you’re having a conversation. Tell your story to every person who’ll listen, and encourage your listeners to suggest ways to make it more believable and emotionally engaging. Present it to your pet and/or yourself in the mirror, because when you say something out loud, it may sound quite different than it does in your head. You don’t need to be perfect, but you do need to practice long enough that talking about your work and your process becomes second nature; you’re comfortable presenting the information and feel confident about your delivery.

When you’re presenting, your objective is to make it seem like you are genuinely and naturally sharing your experiences, thoughts, and ideas.

Good luck.

How to Tell a Story About Your Project

The formula outlined here will help you frame and manage how you tell the stories of your projects. Follow the steps from bottom to top, and add the answers to your project worksheet in Chapter 7.

1. Clearly state the “problem to be solved” in one or two sentences.

2. Communicate two to three key insights from your research that enhanced your understanding of the problem.

3. Connect your insights to the big idea and your solution to the problem. Try doing it in six words or less.

4. Identify the touchpoints and validate why you selected them for the project. Discuss how they support the big idea.