4

Competitive Intelligence as a Vehicle for International Collaboration

Over the last 10 years, competitive intelligence has been used to help increase the competitiveness of companies across the world. We are now proposing that it can be used in a new way to open up numerous exchanges and collaborations. If the Second World War gave rise to East-West blocks and the Cold War, the fall of the Berlin Wall was the start of a new era of world competition: globalization.

We are currently entering a period of competition and struggle which is not yet known today, where the rules of the “game” are no longer stable and can change at any point.

At the same time, technological developments mean that we receive information in a “shorter amount of time”.

This new era has increasing instability across the world, with competition existing between societies states, and regions. In this field, attractiveness is becoming a fundamental advantage for both ensuring international development and ensuring “client” loyalty from those who use products and services.

4.1. The arrival of new signs

4.1.1. Definitions of competitive intelligence

If we refer to the first definitions of competitive intelligence [CAL 05]:

- – “systematic program to collect and analyze the information upon the activities of the competitors […] in view to achieve the strategic goals of the company” (Larry Kahanner) [KAH 97];

- – “analyze the information, upon the competitors which are involved within the decision process of the company” (Leonard Fuld) [FUL 06];

- – “knowledge and forecast of the surrounding world – in view to assist the decision of the company’s CEO” (Jan Herring) [HER 99].

- – we should mention the presence of three important words: information, competitors and company. This clearly shows a type of competitive intelligence focused on the increase of competitiveness of companies. Yet we find new definitions that are opening up way for new applications of competitive (or economic) intelligence, which are broader and have richer collaboration potential.

4.1.2. Maintaining competitive advantages

Maintaining national positions is becoming an issue of the 21st Century. This orientation is clearly indicated in a number of reports that are clear signals highlighting the link between development, innovation, competitiveness and competitive (or economic) intelligence. Let us briefly mention some of these strong signals:

“The U.S. Council on Competitiveness has unveiled a report entitled ‘Innovate America’. Defining innovation as the ‘single most important factor in determining America’s success through the 21st Century’, the report clearly states America’s task in the next 25 years is ‘to optimize [the] entire society for innovation’” [TAM 05].

- – Beffa report (France): for a renewal of French industrial policy [BEF 05];

- – Carayon Report: Competitive intelligence and social cohesion [CAR 04];

- – Renaissance II Report (Canada): Canadian creativeness and innovation for the new millennium [ANA 09].

4.2. Increasing instability

At the same time as previous signals, one must also note rising tensions that are due to multiple factors. Among other things, it is expected that in the next 20 years, the number of independent or quasi-independent states will increase substantially; perhaps even double. This is not without its problems, threatening the global equilibrium. Indeed, certain regions or countries that have achieved, under political pressure and after strong crises, regionalization as a means to maintain some cohesion (e.g. Indonesia after the Asian crisis in recent years) will be faced with the need to ensure minimal development with the fear of seeing these lead to pure and simple independence, which can be seen with the creation of multiple conflicts [GOO 99]. Similarly for autonomous regions, autonomy is now multifaceted, including that of remaining alone before local needs and having to ensure the implementation of local resources alone.

Thus, entire regions are confronted with the need to ensure a certain level of well-being for the local populations, with the fear of opening up conflicts. In this way, two relatively different strategies are emerging for developed countries or for those at different stages of development.

4.2.1. More developed countries

These generally have fewer natural resources and have exhausted non-renewable resources during the period of industrial development; or they have not, like Japan or South Korea, been endowed with them for geological and geographical reasons. The strategy of these countries is therefore to maintain the competitive advantages acquired, and even to create others, by using all the financial and intellectual potential available to develop innovation, creativity and attractiveness. This situation highlights the direct link between technology watch, competitive (economic) intelligence, innovation and creativity.

4.2.2. Low-income countries

Developing countries generally have natural resources, renewable or not. The problem of these countries is not to squander these, but rather to create higher value-added products, for example in the field of agriculture, petrochemicals, steel or rarer metals like copper and nickel. This development will also go through innovation and creativity, but the model will have to be different and will have to take into account the technological level of the country. We cannot go directly from level A to level B, otherwise the effort is too big. We must necessarily go through a certain number of levels which must be determined without concession. It is also necessary that foreign direct investment be more profitable and that technology transfers be provided for in the collaboration agreements. Many countries, in wanting to achieve ambitious goals, found themselves in a worse situation than the departure. Examples like South Korea and formerly Japan are to be revisited, since these countries have ensured a large part of their development by incremental innovation.

4.3. The French example

In France, the first decade of competitive intelligence did not bring developments that were expected; among others in the field of SMIs and SMEs. It was after this observation that the Carayon report was written, followed by the appointment of Mr. Alain Juillet as senior competitive intelligence officer to the French Prime Minister.

A national program of competitive intelligence was then developed, making it possible to raise awareness among the political, institutional and industrial leaders. It was then necessary to establish a system to actually implement the concepts in an industrial environment, then to apply them. This is what has been achieved within the framework of the development of competitiveness clusters, linking institutions, people, research laboratories, industries and institutions concerned locally with the same project.

This will create new partnerships between the public and private sectors, taking into account the triple helix; that is, the new relationships that must be established between government institutions – public or private research laboratories – and industry. This should normally lead the competitiveness clusters to create a development ethic and way of governing that can “save time” and give greater coherence to groups that are still heterogeneous but concerned by one or the same projects. Indeed, if the development of centers like Sophia Antipolis (Nice, France), Research Triangle Park and Silicon Valley (United States) was achieved in more than 30 years, it is obvious that currently this time period is too long and must be shortened. This is the aim of competitiveness clusters.

4.4. Collaboration

The government’s action in the development of a national program of competitive intelligence, as well as its application to regional development, are all actions that are currently being analyzed by different countries, in order to benefit from the gains made in this area by France.

Here, we will have to consider the French-speaking world in the broad sense; that is to say, the countries that seek a possible transposition to their own case, stemming from the French example. The experience that has been conducted in the context of Indonesia, China, Chile, North Africa and Brazil shows that in the field of implementation of competitive intelligence, France is appreciated by its median position between the competitive US system and the business-centric English system. The French system, which gives a large place to intelligence (from the Latin intelligere and non-espionage) is close to developments in Northern Europe among others under the impetus of Dedijer [CLE 04].

From the French example, a method as well as tools can be used and transposed in various contexts. Some space is left to cooperative work, to the taking into account of the national interests and to a rational use of the information (both by its automatic analysis and by the study of its impact by experts in terms of SWOT analysis (strength, weakness, opportunity, threat).

4.4.1. The foundations of collaboration

France having developed a global program of competitive intelligence, not only oriented toward businesses, but also toward national and regional development, has been perceived as a possible model not only by French-speaking countries (through Francophonie), but also by non-French speaking countries such as China, Indonesia, Malaysia, etc.

Cooperation and collaboration can be carried out in many ways, but the five most important ways are: academic collaboration through publications of training and doctorates, bilateral network collaboration, collaboration between associations, collaboration through international institutions and collaboration via chambers of commerce and industry. The following examples are only a selection from many others; they simply illustrate the often personal initiatives from which the French influence in competitive intelligence develops with various countries.

4.4.2. Academic collaboration

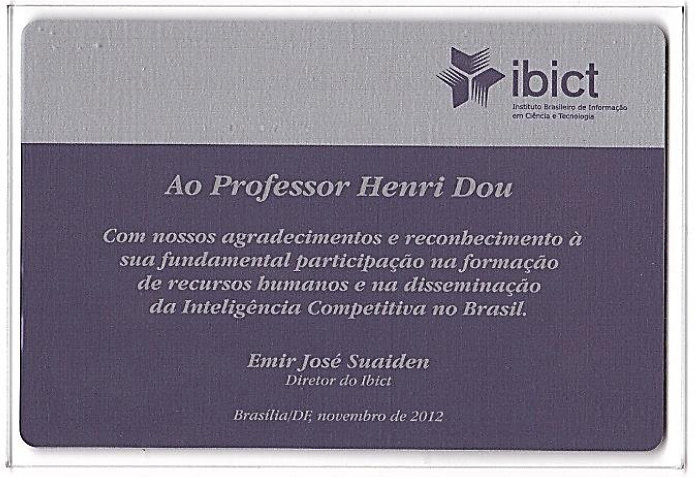

We have to be innovative. In the field, there are two examples that will illustrate this. For more than five years in Brazil, the CRRM, under the direction of Professor Henri Dou, has set up collaboration in an innovative form. Brazil’s Institute of Technology in Rio de Janeiro delivered a Latin American diploma in the field of information (lato sensu). An agreement was concluded between this center and the CRRM University Aix Marseille III, to complete the previous diploma by Advanced Studies course then the master (when one has applied LMD degrees, masters, doctorate) essential to a knowledge of the eve of technological and competitive intelligence. These courses are those given at Marseille CRRM; they were conducted in Brazil following a particular approach (whose leader is Gilda Massari Coelho). Several training centers were developed: Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, Salvador de Bahia and Natal, teachers passing from one to the other. The students according to their results obtained the Advanced Study course or the master of the University Aix-Marseille III or only the lato sensu diploma of the INT. All training was done within a “continuing education” framework. Registrations were held jointly with Aix Marseille University and INT, the defense proceedings of the dissertations (Advanced Study or master) taking place in Marseille. Classes were conducted in Brazilian Portuguese or English.

This collaboration then allowed various Brazilian students to do PhDs at Aix Marseille III University, as well as UTV (University Toulon Var). The result of this organization is that currently, in all major Brazilian industries, there are people in key positions who have completed their studies within the French system. The conclusion of this experiment, which has now finished, has made it possible to train about 120 students in five years (Advanced Study, masters, doctorates and lato sensu diplomas, including 40 Advanced Study courses or masters, and 15 theses). At the pace of classical academic exchanges and given the number of scholarships that could have been attributed (we can doubt the competition between disciplines) it would have taken more than 30 years at best to achieve the same result.

This one-of-a-kind training initiative was hailed by Brazil’s Ministry of Industry Development and Foreign Trade and by the IBICT [CIW 08, CIW 12, MAS 06].

Figures 4.1 and 4.2 are commemorative plaques from the Ministry of Industry and Trade Development for the commemoration of the 10 years of the beginning of competitive intelligence training (Figure 4.1) and the development of collaborative competitive intelligence with Brazilian creativity and innovation for the new century, IBICT1 (Instituto Brasiliera Informacao Cientifica e Tecnica) (Figure 4.2).

The same experiment was conducted with Indonesia with the North Sulawesi region, with the exception that many scholarships were awarded by the Indonesian government, the governor of North Sulawesi or some local mayors, plus some French scholarships. Courses were conducted in Marseille or Indonesia. More than 60 students have been trained in Advanced Study programs or masters and 21 doctors. We can make the same remark as above about the effectiveness between time and the number of students trained. Currently, there are many students trained in competitive intelligence in universities (lecturers, professors and rectors), industries, banks in Indonesia, or at the political level (elected in provincial councils, mayor, etc.).

It is simply regrettable that the CRRM2 no longer exists because of the retirement of some of its leaders and the non-replacement of their position in the discipline. It is obvious that the misunderstanding of the finality of competitive intelligence and technology watch by the leaders of Aix Marseille III University played a key role in this decision.

4.4.3. Bilateral network collaborations

The bilateral network collaborations are due to the invitation of French researchers in the field. These are not official missions. These include international symposia organized in Indonesia, Chile, China and Morocco, and observatory projects such as CACIMA3 [REN 18]. The following few examples illustrate this type of international collaboration, the French experts being invited by the organizers.

Figure 4.1. Competitive intelligence development in Brazil

Figure 4.2. Recognition of the Brazilian competitive intelligence training by the IBICT

Figures 4.4 and 4.5 illustrate interventions in Canada and Vietnam. For Canada, this was a meeting of the CCI St Pierre et Miquelon and New Brunswick (Dieppe), in 2013. In Vietnam, the meeting was held in Hanoi at the IAB (International Advisory Board) in 2011. Patrick Gillabert (Director UNIDO Viet Nam CRRM’s Alumini), Philippe Clerc (CCI France) and Henri Dou, were present with various international experts.

Figures 4.6 and 4.7 show meetings in Morocco and Indonesia. One of these took place at the Open University of Dakhla in 2010 for the signing of collaboration agreements between the university and the International Francophone Association for Competitive Intelligence. The other took place in Jakarta for “Indonesia 2025”. We can see Philippe Larrat (Atelis), Alain Juillet and Julietta Runtuwené (currently the Rector of Manado State University, having completed her PhD at the CRRM).

Figure 4.3. 2014 Symposium in Beijing: Philippe Clerc and Henri Dou were invited as experts [DOU 14]

Figure 4.4. Second competitive intelligence meeting, Canada, 2013 [CIW 13a]

Figure 4.5. International Advisor Board, Vietnam, 2011 [IAB 11]

Figure 4.6. Meeting at the Open University of Dakhla, 2010 [CLE 14]

Figure 4.7. Indonesia in 2025 – International symposium, Jakarta, 2011 [UNI 55]

4.4.4. Collaboration between organizations

The International Association of Competitive Intelligence plays a big role here. Born out of the motivation of a group of French experts of competitive intelligence, this organization managed to create many new collaborations. The following photographs are some examples of this.

Figure 4.8. Signing of the collaboration agreement between the AIFIE4 and the Association of Competitive Intelligence of the Hunan province (China), 2011 [CIW 11]

Figure 4.9. Franco-Chinese seminar on applied competitive intelligence for companies in Changsha (China), 2012 [DOU 12b]

Figure 4.10. Competitive Intelligence and its International Implications, 2013 [CIW 13b]. International symposium organized in Ajaccio by the Corsican Territorial Collectivity and the SFBA5, following the invitation of a Chinese delegation. Left to right: Philippe Clerc, Henri Dou, Alain Juillet, Qihao Miao (Shanghai Library)

Figure 4.11. Reception of an Indonesian delegation at CCI France [UNI 55]. Business meeting between the AFDEI (French association for Indonesian economic development) and the AIFIE

4.4.5. Collaborations through international institutions

In this context, French experts are solicited by international organizations (CIT Geneva), WIPO, OAPI and the European Union (for example the PASRI Tunisia program) to participate in international seminars or training sessions.

Figure 4.12. Addis Ababa certificate courses (Ethiopia), 2011 [DOU 12a]. Collaboration with the WIPO6 in Ethiopia. Experts: M. Getachew (Ethiopia) and Henri Dou

Figure 4.13. PASRI7 program. Research and Innovation System, Tunis (Tunisia), 2014 [CIW 15]

Figure 4.13 illustrates an expertise requested by the European Community in the PASRI program in Tunisia. The research and innovation system support project (PASRI), a project funded by the European Union, for 12m euros over four years (2011–2014), aims to provide solutions to the main problems identified at the level of the various actors of the innovation chain starting from the company which is in direct relation with the consumer market and employment and arriving at the unit of research which accumulates scientific and technical knowledge, including the full range of institutional, administrative, financial, technical and academic stakeholders that are expected to support the transformation of technical knowledge into products, or tangible services.

Figure 4.14. Competitive intelligence and certificates, Douala (Cameroon), 2010 [OAP 10]. Certificate course for competitive intelligence and information analysis. Course seminar organized by the OAPI8 and the WIPO

4.4.6. Collaboration via chambers of commerce and industry

In this context, the CCI of France is particularly active, as well as the Franco-African Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Some events are also supported by the European Union. We can also mention the university of consular cooperation with emerging countries [REN 10].

Figure 4.15. International conference on competitive intelligence, Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso), 2011 [CCI 11]. Competitive intelligence in Burkina: territorial development scheme. Organized with the collaboration of CCI France, the European Union, the CCI of Burkina Faso, and the Franco-African CCI

Figure 4.16. Meeting of the consulate chambers of commerce, Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire), 2009 [CPC 09]

4.5. Conclusion

It is noted that in this set of international collaborations aimed at promoting a competitive intelligence “à la française”, the initiatives come in most cases from foreign countries or foreign institutions. At the French level, it is more particularly personal initiatives that underlie collaboration. France has developed a national program of competitive intelligence, but even if it is a proven vehicle of collaboration, it is clear that these come from either foreign partners or personal initiatives. We have therefore not grasped the importance of this vehicle, which supports Tenzer’s vision [TEN 09] on the loss of French influence in international bodies.

4.6. References

[ANA 09] ANANIADOU K., CLARO M., 21st century skills and competences for new millennium learners in OECD countries, Working document no. 41, OECD, 2009.

[BEF 05] BEFFA J.-L., Pour une nouvelle politique industrielle, La Documentation française, Paris, 2005.

[BON 99] BONIFACE P., “Danger prolifération étatique”, Le Monde Diplomatique, January 1999.

[CAL 05] CALOF J.L., Building your CI capacity and gauging the effectiveness of your CI system, Presentation, Competitive Intelligence Asia Pacific conference, Shanghai, September 2005.

[CAR 04] CARAYON B., Rapport sur la stratégie de sécurité économique nationale, Assemblée Nationale, Paris, 2004.

[CCI 11] CCI DU BURKINA FASO, EUROPEAN UNION, RIC PROGRAM, Competitive intelligence, innovation and competitiveness strategies, Burkina Faso, 2011, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=1136.

[CIW 08] CIWORLDWIDE, Development of competitive intelligence: Result of the administrative inquiry of the Brazilian Ministry of Education”, May 29, 2008, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=39.

[CIW 11] CIWORLDWIDE, Third Franco-Chinese seminar on Competitive Intelligence, Paris May 18–20th 2011 – ACFCI, Paris, France, May 26, 2011, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=1073.

[CIW 12] CIWORLDWIDE, Brasilia, Tenth Brazilian Workshop on Competitive Intelligence and Knowledge Management – Homage from IBICT to Professor Henri Dou, Brasilia, Brazil, November 28, 2012, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?s=brasil.

[CIW 13a] CIWORLDWIDE, “Deuxième rencontre en intelligence compétitive (intelligence économique)”, Second Competitive Intelligence Symposium, Dieppe, Canada, March 25–27, 2013, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=1488.

[CIW 13b] CIWORLDWIDE, “Les sciences de l’information et leurs implications géopolitiques”, Information Science and its Geopolitics Implications, Ajaccio, Corsica, November 28 and 29, 2013, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=1592.

[CIW 15] CIWORLDWIDE, Second session of the PASRI − Tunisie − Propriété intellectuelle et contractualisation − Analyse automatique des brevets et innovation, October 9, 2015, available at: http://s244543015.online-home.fr/ciworldwide/?p=1842.

[CIW 17] CIWORLDWIDE, The venue of two important Delegations from Indonesia in France, June 29, 2017, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=2042, and: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=2020.

[CLE 04] CLERC P., “Hommage à Stefan Dedidjer”, Regards sur l’IE, no. 3, 2004.

[CLE 14] CLERC P., DOU H., “Du soft power au smart power. Quelles stratégies d’influence ?” and “Quelle stratégie de soft power pour le Maroc ?”, Diplomatie, Les grands dossiers, no. 24, 2014–2015.

[CPC 09] CONFÉRENCE PERMANENTE DES CHAMBRES DE COMMERCE AFRICAINES ET FRANCOPHONES, 35e Assemblée Générale, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, November 11–13, 2009, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=773.

[DOU 12a] DOU H., DOU J.-M., GETACHEW M.-A., “Automatic patent analysis: Technological strategic dependence”, Beijing ICTCI 2011 in Progress in Competitive Intelligence, Peking University Press, Beijing, pp. 173–192, 2012.

[DOU 12b] DOU H., CLERC P., Franco-Chinese seminar of competitive intelligence − Using sectorial and territorial intelligence to serve the local economic development, CiWorldWide, Changsha, China, November 13, 2012, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=1417.

[DOU 14] DOU H., “A new way to understand the ‘force field analysis’ from Big Data analytics may be the future engine of the smart cities development”, Beijing Symposium on Competitive Intelligence, Peking University Press, Beijing, 2014.

[IAB 11] IAB, “The international advisory board of the Ministry of Science and Technology of Vietnam. Innovation, strategy, competitiveness, competitive intelligence”, UNIDO, Hanoi, 2011, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=1183.

[KAH 97] KAHANER L., Competitive Intelligence: How to Gather Analyze and Use Information to Move your Business to the Top, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1997.

[MAS 06] MASSARI G., DOU H., QUONIAM L. et al., “Ensino e Pesquisa no campo da Inteligência Competitiva no Brasil e a Cooperação Franco-Brasileira”, Puzzle, Revista Hispana de la Inteligencia Competitiva, vol. 6, no. 23, pp. 12–19, 2006, available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Dou_Henri/publication/304626163_Ensino_e_Pesquisa_no_campo_da_Inteligencia_Competitiva_no_Brasil_e_a_Cooperacao_Franco-Brasileira/links/577a67d508ae355e74f068a7/Ensino-e-Pesquisa-no-campo-da-Inteligencia-Competitiva-no-Brasil-e-a-Cooperacao-Franco-Brasileira.pdf.

[OAP 10] OAPI WORKSHOP, Regional forum on intellectual property and exploitation of the research results in Africa, Douala, Cameroon, 2010, available at: http://s244543015.onlinehome.fr/ciworldwide/?p=980.

[REN 10] RENARD T., La vision française de l’IE à l’épreuve des pays émergents : Approches bilatérales et multilatérales, Université de la coopération consulaire, Jouy-en-Josas, France, 2010, available at: https://fr.slideshare.net/ThibaultRenard/la-vision-franaise-de-lintelligence-economique-lpreuve-ucc-2010.

[REN 18] RENARD T., “Projet CACIMA : L’observatoire d’information économique franco-canadien”, Intelligence économique des territoires, pp. 181–183, CNER, Paris, 2018.

[TAM 05] TAMADA S., “Innovation-oriented industrial policies needed”, RIETI, January 25, 2005, available at: https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/columns/a01_0158.html.

[TEN 09] TENZER N., La France disparaît du monde, Grasset, Paris, 2009.

[UNI 55] UNIVERSITAS NEGERI MANADO, website, 1955, available at: https://www.4icu.org/reviews/universities-urls/10169.shtm.