7

Sphere of Influence

In this chapter, we have chosen to illustrate the fruitful articulation between the competitive intelligence approach and strategy through a “strategy of influence” approach inspired by the field of geopolitics [CLE 11]. In 2001, strategist Richard D’Aveni [DAV 02] showed how global companies achieve “supremacy” through influence by shaping the market to their advantage through the construction of spheres of influence, real competitive arsenals, and playing a mix of confrontation, cooperation and competition. In this, it illustrates what we call, among others, strategic invention or strategic innovation, essential steps that are the motivation of this book. The analyst D’Aveni debates the doxa on business strategies, hybrid analysis matrix companies with those of geopoliticians. Chambers of commerce and industry, in France, used this matrix both to think about the strategies of SMEs, clusters of companies, but also local development strategies in the French regions [DOU 16]. They used it as a matrix for organizing prospective approaches to think about their own future. This chapter illustrates the creative capacity of the competitive intelligence approach, which tirelessly links, crosses, associates, cross-fertilizes and never separates to brave the uncertain, the unforeseen, even the unknown. It also reinforces the positioning of competitive intelligence as “daughter of strategic intelligence” [BLA 06].

The strategic thinking and the steering of strategies that we describe as influencing the territories of the world modeled by a conflictual globalization therefore concern companies, like states and territories, and finally any organization in search of strategic positioning.

Before describing the concept of the sphere of influence, its implementation and advancing illustrations, we wish to return to key observations and definitions that will help to establish the relevance of the dynamic matrix of spheres of influence.

7.1. The return of geopolitics in the economic field

Analysts at the geopolitics study center of Grenoble management school [GRE 17] alert us to the lack of appetite of corporate decision-makers for geopolitical issues and their priority consideration in their analyses and strategies. On the other hand, public decision-makers find it difficult to integrate political and economic forces into their strategic thinking.

France, however, poses the problem well through the strategy of competitive intelligence that it implements since the first experience constituted by the establishment of the Committee for Competitiveness and Economic Security (CCSE) in 1995 [CCS 95]. Does this strategy make it possible to maintain its industrial and cultural identity, to strengthen its bargaining power at the heart of the major globalized networks of dominance (industry, technology, knowledge, information) and to fight against the multiple risks of dependencies: resources, talents, data?

In a way, it is a question of questioning the soft power of France, the tools of its power, its capacity of collective intelligence of the world in order to brave the entirely new challenges of the period.

There is an urgent need to integrate in our strategic anticipations the priority of geopolitical and geoeconomical – as we will see later – for at least three reasons.

First, because the analysis units of balance of power situations in the global economy have changed [DAV 12]. A shift is taking place from competitive strategies for large groups to competitive strategies for nations and their networks of allies. The case is not new. Geopolitics, the object of which is the study of the interaction between space and rivalry for power, space and the search for power, concerns companies just as much as states.

Then, because of the disintegration of the international system and the advent of a globalization of crises and helplessness, a phase of “strategic chaos” Nicole Gnesotto as described by [LAM 17], geopolitical specialist at the CNAM, in a recently published dialog with Pascal Lamy, former Director General of the WTO.

Finally, because “for decades never, has the world appeared so unstable, so unpredictable, so indecipherable”. When the very notion of “strategic surprise” becomes the paradoxical foundation of the global system [AML 17], it is necessary “to explore the almost infinite complexity of the facts” and to mobilize the “ability to understand the forces, movements and contradictions of the globalization”.

These observations refer us to the choice of the analysis matrix: geopolitical or geoeconomic [LAM 17]. The latter, born in the early 1990s, deals with the interaction between space and economic and commercial confrontation led by the states in the context of competitiveness and economic security policies in search of a position of influence and power, promotion and protection of national strategic sectors. Exploring the complexity requires the complementary use of the two analysis matrices.

To deal with this challenge, the implementation of competitive intelligence as a way of thinking economic and cultural power struggles and as a mode of action to control them, is clearly understood as a “strategic action” approach that is in agreement with the work of Habermas [HAB 87]. In the strategic activity, the actors coordinate their action plans by means of the influence they exert on each other, aiming at success, “the will to influence others with a view to the satisfaction of his own interests” [HUY 05].

It is important to stress here the central positioning of influence strategies in the competitive and cooperative arsenals of states, territories, companies and actors engaged in the issues of civil society. As the central pillars and history of competitive intelligence, the influence and strategies that implement it have become preeminent in increasing the power of both nations and companies [DAV 02]. They are the major vehicle for steering economic and cultural power struggles [CLE 08].

7.2. Power strategy and influence strategy

For companies and states, conquering and surviving requires strategy, hence the need to develop a culture of strategy and strategic thinking [ZAI 13].

7.2.1. States

Thus, Joseph Nye, through an abundant literature, analyzes the key drivers of power [KEO 98]. He questions the ability of a country to control the international environment to lead other nations to act according to its views: typically illustrated by the will of successive American public authorities the slogan “shaping the world” [TUS 16] or the promotion of the social market economy model by the Germans as a model for Europe.

Joseph Nye gives us an effective definition of these dynamics:

“Power is the ability to develop a real influence on others by causing them to act according to its own interests. It manifests itself in the form of hard power that uses radical methods such as coercion and corruption or soft power that tries to convince by seduction and persuasion” [NYE 13].

It is like “acting on the situation so that it produces the desired effect for your interests or how to make the other do what you want them to do” [HUY 11].

In addition, he notes that “the new globalization” is distinguished by the emergence of new actors, including collectives whose power and influence will gradually increase. Also, to develop power and influence in a globalization where power is distributed requires maintaining alliances and creating new networks articulating hard power (power of coercion) and soft power (power of attraction and persuasion). It then becomes essential to develop “contextual intelligence” of stakeholders and situations to adjust cooperation and development strategies [CLE 15a]. Here, culture becomes the epicenter of the balance of power and growth strategies [CLE 08].

In this spectrum, let return for a moment to the discipline of international political economy. With its American, Canadian and British “branches”, it aims to “build tools to analyze the balance of political power influencing globalization”. The definition that Susan Strange [STR 15] (English school) gives power integrates, in our view, both the approach of the American Nye soft power and that of the influence of D’Aveni. The power it qualifies as “structural” consists of “the ability to elaborate, decide, legitimize, implement, control the rules of the game of globalization which others must necessarily accept”.

Seeking to answer the ambitious question “who holds the power in the world economy? Banks, states, the G20, Google?”, Susan Strange sees the “spread of power around the world”. Traditional and new actors (NGOs, mafias and criminal networks, etc.) are all trying to influence global political relations in their favor. To conclude that, through confrontations and negotiations, the actors generate “national, regional, international public standards, private standards and areas of non-governance. All these rules constitute a moving and evolving universe” [STR 15].

7.2.2. Companies

Schematically, two major schools of strategy of organization can be distinguished [LER 08].

7.2.2.1. Positioning strategy

It is for the organization to adapt to its environment and the fields of power/confrontation it undergoes and must control. It is about acquiring and maintaining a competitive, “differentiating” advantage over rivals. By strategic positioning, the organization then seeks this differentiating advantage and for that, must conduct an analysis of its positioning in a given context (techniques and methods of competitive intelligence: analysis matrix of strengths and weaknesses, opportunities, threats) [HUY 05]. It thus defines the field of rivalries, and leads to identifing the key factor of the advantage it holds to define the type of offensive and/or defensive strategy that it wishes.

There is a more recent approach that is formulated as follows: adapting to its environment today is no longer enough (positioning). Conquering and building the competitive advantage becomes the operating mode.

7.2.2.2. Influence strategy

The “strategist” organizations think and drive renewed strategies, consisting of changing the rules of the game and the balance of power. It is simply called “influence”. How can one influence the forces/stakeholders at work in the active environment of the organization to give the organization a “power of influence”, an advantage. “How do you get stakeholders to do what’s in my best interest, that of the organization and its members?”

The perspective of strategic analysis is reversed: the focus is on the organization’s ability to use and transform the environment for its own interests, vision and key objectives to gain bargaining power, the power of coercion. The organization uses a differentiating and strategic advantage, namely its resources and skills. Resources are strategic, tangible and intangible assets (know-how, reputation, goodwill, etc.). Competencies implement, organize and combine resources to provide customers with products or services that have significant value. The competitive advantage lies in the innovative exploitation of the key competences of the company. Here, context analysis is done through the lens of resources and skills.

The latter approach is the one now chosen by many public and private organizations at the international level. The strategy and the strategic analysis that feeds it are based on key competencies, market shares, product lines, price competition, differentiation, unique value for the customer, and operational excellence.

But, for US strategist Richard A. D’Aveni [DAV 02], this is not enough to configure strategies. Since the 2000s, to observe and study the fighting that multinationals and other large groups engage in – or do not engage in (decision not to position in certain product/market segments) – he comes to prescribe the need for companies to analyze their sector of activity as systems of power and develop in this respect strategies of power vis-à-vis the other actors of the sector. Beyond the operational excellence, it is for “the strategic supremacy” that the company must aim, explains the American strategist. The latter thus completes the arsenal of strategic business thinking – “core competencies”, product strategy, customer orientation – notably by introducing the concept of spheres of influence, as an arsenal intended to prevent short-sighted strategies – “blind spots”, the certainties and other “strategic tensions” of decision-makers. How does Richard D’Aveni define “strategic supremacy”? It consists of three principles of power. In our opinion, they correspond to a strategy of competitive intelligence: the power of perception first, understood as intelligence of the situation, competitive situations and key drivers of the influence of the company and competitors in its markets. The second power is the power of influence over customers: “capture their hearts and minds”. Finally, the third is that of shaping a favorable environment by using different competitive and cooperative combinations and models.

7.3. The sphere of influence: illustrations

After defining and describing the different spaces constituting a sphere of influence and their functions, we will try to apply and implement the strategic matrix. From the sphere of influence of a company, we will describe how the French assembly of chambers of commerce and industry, CCI France, declined the matrix for use in the regional territories.

7.3.1. Definitions

According to Richard D’Aveni, who brings political economy into the company, throughout history, spheres of influence as a geopolitical concept are used in the management of power relations between countries. He takes the example of the sphere of influence of Rome during Antiquity and describes the dynamics of the spheres of influence of the Cold War – the Western and the Soviet. Nations are pursuing these strategies today. They are also, in his view, the effective, if not the best, path to establishing a profitable business order in the world’s markets. Companies expanding their hold on these markets have interest in thinking about their strategy in terms of increasing power and spheres of influence. The strategist defines the latter as the “product-geography” zones over which the company holds a decisive influence over the players in its sector of activity, as well as within the competitive power relationships that are active on it. Through the sphere of influence designed, the company redefines its product portfolio.

The purpose of the sphere of influence is to promote, defend and protect one’s position. A sphere of influence is built up from existing positions, acquired positions and assets. This set, which contributes to support the company, must be supplemented by a clear strategic intention serving the sphere of influence. It is necessary to define the area of influence (regional, national, international) on which decision-makers want to establish a leadership or to develop in cooperation by strategic supremacy, before defining the fields of activity which will contribute to strengthening this influence. A well-built sphere of influence will help push competitors into a “corner” of the market, reduce the price war by “the threat of mutually assured destruction”, “encourage competitors to develop on non-confrontational markets”, and ultimately shape the sector of activity to the mutual benefit of each.

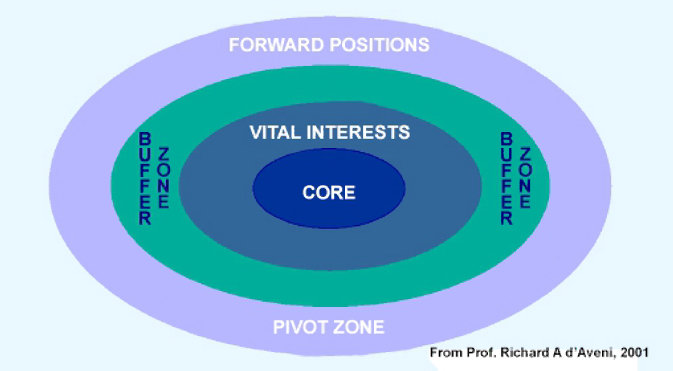

A well-constructed and controlled sphere of influence is made up of the following areas (Figure 7.1).

The core of the sphere represents the central and essential part. The company draws from these resources and core competencies the revenues essential to its survival and growth. It is not the “core market”, but geographical areas where the company or entity has a decisive influence or the product from which it derives its main incomes.

Vital interests, in the sphere, consist of geoeconomic activities that provide the business or entity with the ingredients of its power. These are key assets for the performance of the core business. These activities contribute to the profitability of the products/services of the core (goodwill, anticipations of new needs, consumers’ uses or new customers).

Advanced positions or forward positions have an important function of preparing market access and prefiguring new offers (innovation) that will enrich those of the core. These are essentially core-like product/market packages, but deployed by strong competitors. The advanced positions of the company are close to the core of the competitors’ spheres. For example, the company may launch harassment attacks on the competitor and divert its attention and resources while investing in other markets. This is an observation post much closer to the competition.

Buffer zones protect the core against competing intrusions and predators. As zones of resistance to attacks, they make it possible to measure/analyze the offensive capacities of the competitors. In concrete terms, these are market and product areas in which the company uses a “blocking brand” against a price attack by competitors, customers in this area being more sensitive to the brand than the price.

Pivotal zones, finally, are markets (geographical areas) which can shift the balance of power to areas of establishment of competition. It is about moving the strategic pivot of the company or entity and taking a position in markets or a geographic area as a “bet on the future” [MOR 00].

Richard D’Aveni also refers to competitive spaces as “void of power”, that is to say no serious competitor is established on them.

Figure 7.1. The different parts of the sphere of influence (according to Richard D’Aveni)

We wish to make some observations here. First of all, the concept of a sphere of influence and a new way of targeting strategic supremacy is essential when the market has become a permanently changing structure (geography, product segment, services, positioning product or services, etc.), disturbed by the disruptive dynamics of hypercompetition and breakthrough innovations born of the digital revolution.

Second, the dynamic nature of the spheres of influence matrix, which complements the strategic concepts already in play, should be noted. In addition, the concept of sphere of influence is an agile device of permanent intelligence of situation, mobilizing capacities of anticipation and diversified analysis. Each zone of the sphere of influence is a function of monitoring a specific reality of the competitive confrontation: the buffer zones that are subject to the attacks of the competition make it possible to collect information on the behaviors, the intentions and the capacities of the competitors. Advanced positions are also business intelligence devices designed to detect innovations and needs of client groups. What about pivotal areas, also organized to gather information on future markets and prepare future developments of the heart? Finally, the sphere of influence represents as many drivers for action and stratagems. The arsenal it represents will help to reduce the sphere of influence, thus the power of a competitor, by enclosing it on its own core.

7.3.2. The sphere of influence of a company

Now, let us try to illustrate the concept of the sphere of influence through proofreading – as another interpretation – of IKEA’s international development strategy. Why this choice? IKEA is quoted extensively by Michael Porter in his long article “What is strategy?” as a company illustrating the strategic positioning approach [POR 08]. For his part, Richard D’Aveni debates the usefulness and operationality of the analysis of Michael Porter (the five forces) in view of the advent of new relations of power qualified as hypercompetition. Indeed, he considers his view to be “incompatible with Michael Porter’s strategic analysis, whose general models are useful when the competitive advantage comes from the structure of the sector, namely, when it comes to creating an oligopoly based on the five forces”. But, according to D’Aveni, hypercompetion considerably modifies the situation: new competitors, challengers carrying disruptive behaviors [DIR 16]. It reconsiders the five forces and seeks, through strategic innovation, not the perpetuation of acquired positions, but rather, how to act to disrupt or challenge the advantages created by the five forces (barriers to entry, oligopolistic prices, etc.).

In imagining the operating concept of the sphere of influence, he wants to answer the following essential questions: “how do the established leaders maintain their position in the market and how do they react when a rebel or revolutionary movement agitates their sphere of influence?” Thus, building on this opposition, we attempted to re-read the story of IKEA’s international expansion of IKEA by Clayton Harapiak in 2013 [HAR 13] by interpreting it in terms of the strategic concept of the sphere of influence. We therefore want to establish a perspective on Richard D’Aveni’s concept and show its amplitude compared to reading, for example, Michael Porter.

It is only a simulation, an essay from work done with students from the Institute of Business Administration of the University of Lyon 3 and Skema Business School during the year 2017.

Michael Porter [POR 15], defining strategic positioning, writes:

“A company can outpace its competitors only if it makes a difference that it can preserve”.

He takes several examples of strategy and is interested in IKEA.

“IKEA has a clear strategic position. The Swedish-based global furniture manufacturer is targeting young buyers who want cheap style. This marketing concept is converted into a strategic position thanks to the set of customized services offered. IKEA has chosen to do business differently.”

This differentiation takes place compared to the traditional furniture manufacturer whose value chain optimizes personalization and service, but at a high price.

“On the contrary, IKEA is aimed at customers who have no problem making a concession on the service in favor of the price.”

The strategic positioning approach is certainly very useful in defining the major asset of the company.

When a company like IKEA enjoys a clear strategic position, the mapping of its activities reveals the major strategic themes that Richard D’Aveni defines as the heart of the sphere of influence. There are four for IKEA: “limited customer service, direct customer choice, modular furniture design, low manufacturing cost”. They are then implemented by a set of linked and combined activities, which underpins the strategy and choice of positioning, competitive advantage and sustainability: transport provided by the customer, catalogs, displays of explanatory information, great variety and simplicity of manufacture, assembly of furniture by customers, stores in the suburbs with extensive parking, vast stocks on site, etc.

Let us now try to define IKEA’s sphere of influence and question its strategy on the basis of Clayton Harapiak’s monograph [HAR 13].

The Swedish-based core has been defined around the four major themes. The core and the development of the “IKEA concept” that they defined allowed the company to nourish its growth by progressing in other markets, other geographical areas. In 1974, IKEA developed in a nearby market, West Germany. In 1982, the company moved to Canada and in 1985 to the United States.

The vital interests that reinforce and sustain core growth can be defined at IKEA by design expertise, including eco-friendly products, compact packaging, economies of scale, simple transportation, and large on-site inventory, storage throughout the year, and especially additional services in stores (attractiveness). This is the example of access to the Chinese market that has revealed that the consolidation of the brand image was around the restaurant located in the store and attended by Chinese consumers as a family.

The buffer zones are assured for IKEA by the goodwill of the brand, the capacity for innovation, the 100% provision from suppliers over the long term guaranteeing cost control and quality, especially compared to imitating competitors. IKEA’s markets with significant sales volumes are security positions to ensure economies of scale and competitive advantage.

Advanced positions will be used by IKEA to penetrate new markets. The company chooses highly competitive markets where, as in Japan or the United States, powerful competitors in the furniture sector are located.

We can imagine here that IKEA will try to take a position by destabilizing the competitors (Walmart, Kmart, Target, etc.), by disrupting the market with prices, even if it does not win anything. Advanced positions that get closer to the core of the sphere of competitors (Japan, China, United States, etc.) will serve as advanced positions to capture the innovations of competitors and adapt products to consumption patterns. The positioning of stores in cities in China and not in the suburbs could serve as an experiment for other markets.

Finally, a pivot zone stands out to build the future of the company. It is China, whose potential is considerable whereas the competition is relative. IKEA enjoys a good brand image through the restaurants located in the shops and the surprising practice of the Chinese who come to sleep on the beds in the exhibition halls. The company has been able to locally produce furniture and display costs 70% lower than other markets.

7.3.3. The sphere of influence of a territory

The objective of a territory’s sphere of influence is to structure the power needed to modify the balance of forces (influence) within its strategic environment in favor of the interests of its population, its tangible and intangible assets, of its human capital. Ultimately, it is a question of serving the power interests of this territory, namely, for the decision-makers, to impose their will on the stakeholders of their environment, to dissuade initiatives that could thwart their plans and to contain or constrain the ambitions competing territories. The power interests of the territory are deployed particularly in the battles of attractiveness of “intelligences”, skills, foreign investments, etc.

7.3.3.1. How to deploy the power interests of a territory

The strategic positioning of a territory in the European and international competition invites territorial leaders and decision-makers to develop a strategy of power, consisting in acquiring the capacity and power that results from influencing or even defining the competition or cooperation rules of the game [DAV 02]. Thus, territorial decision-makers are able to define the boundaries of their territory and shape those of their competitors. They thus establish a sphere of influence allowing them to define their strategic options according to different areas of competitiveness. They thus master key issues such as addressing the risks of strategic dependencies, increasing the attractiveness of the area and opening up new development prospects.

This modeling allows decision-makers to develop their strategic intentions in a coherent framework that fosters threats or opportunities arising in the competitive and economic environment through greater maneuverability, active listening and the deployment of competitive advantages.

Such an organization also makes it possible to weave an extensive and effective system of power through the multiple links that make up the network of alliances of a territory. It facilitates the exposure of its attractiveness factors without resorting to direct confrontations. Finally, these zones of influence can be activated to force the “challenger” territories to disperse or weaken their forces.

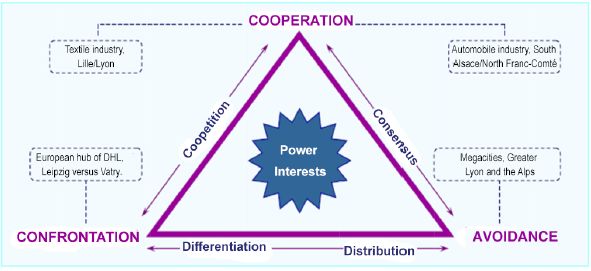

It should be recalled here that to design and pilot a strategy based on a sphere of influence, territorial decision-makers have several modes of strategic mediation. These are all modes of operation chosen to reduce the constraints and the risk-taking in the engaged maneuver. They come in a strategy of confrontation, avoidance or cooperation (Figure 7.2).

Direct confrontation consists of differentiating oneself by competition (price, investment, influence, etc.) and having the power to negotiate with the key players in the environment. The city of Vatry in the Marne had in 2003 chosen to face the city of Leipzig in Germany in the fight whose stake was the implantation of the DHL sorting platform (1,400 jobs); Vatry lost. Avoidance makes sense in the relationship between the weak actor and the strong actor; avoidance allows one to leave the risky confrontation and to lead a strategy “knowingly”, but also to distinguish oneself by sheltering direct confrontations and rebuilding one’s bargaining power. In the battle of metropolises and their power, Grenoble Alpes Metropole has made the choice of avoidance vis-à-vis Greater Lyon. To survive and not lose their identity, decision-makers have chosen to distinguish themselves from others. Cooperation allows for the establishment of agreements/agreements, but also cooperation with the “competitor” (coopetition) on themes and objectives that are shared and less competitive.

Figure 7.2. The modes of strategic mediation

Therefore, the construction of a sphere of influence requires the control of its components as defined by the strategist Richard D’Aveni.

7.3.3.2. Zone definitions of the sphere of influence of a territory

The core includes the economic activities through which the territory receives most of its income. The territory is master of the rules of the game on its core. This is the part that it absolutely must preserve for its economic security. This is the area of geoeconomic influence where lies its “supremacy”.

Vital interests represent the area that consists of activities that, by themselves, are unattractive by their density or profitability, but that contribute to the territory’s position in its environment and to the attractiveness of activities located in the vicinity of the nucleus. These activities ensure the success of the “core”.

Buffer zones consist of activities that prevent a competing territory from claiming to be able to attract the activities of the territory within its core. It is an “airbag” zone that is also used to detect the movements and intentions of the stakeholders, through its network of partners.

Advanced positions are combinations of activities that are developed in partnership with public or private organizations from allied territories, in order to have real “bridgeheads”, capable of providing a critical advantage over competing territories. These activities, the fruit of strategic alliances, can also contribute to accelerate the entry of the territory into innovative fields or targeted geographical areas, to catch up with competitors or to counter the desire for a dominant position in another territory.

Pivotal areas consist of activities or geographical areas of interest in which the territory invests to plant milestones in anticipation of future development opportunities. This zone also makes it possible to prevent a territory from holding a dominant position in the future that would have the effect of displacing the balance of forces in a market or a geographical area, or even risking a strategic dependence.

7.4. Conclusion

A company, a territory, a region or an institution have in any case a zone of influence, whether material or immaterial. It is therefore necessary above all to know their influence factors and the area in which they are exercised. Then come the operations of defending these privileged areas, and extending them. But in a fast-moving world, these zones can vary according to the competition, geopolitical events and technological evolutions. This means that the current positions should not be taken for granted and we should always have in mind that they can evolve positively or negatively. Protecting and expanding these areas is imperative for any organization; it comes with the need to have the necessary information and to analyze it on a dynamic and prospective basis [CLE 15b].

7.5. References

[BLA 06] BLANC C., DELBECQUE É., OLLIVIER T., “Intelligence économique : Quand l’information devient stratégique”, Hermès, La Revue, vol. 1, pp. 87–91, 2006.

[BON 03] BONDU J., “Francophonie et sphères d’influence”, Inter-ligere, 2003, available at: http://www.inter-ligere.fr/index.php/fr/geopolitique/254-51francophonie-et-spheres-d-influence.

[CCS 95] CCSE, “Comité pour la compétitivité et la sécurité économique”, Les Échos, April 12, 1995, available at: https://www.lesechos.fr/12/04/1995/LesEchos/16877-134-ECH_comite-pour-la-competitivite-et-la-securite-economique.htm.

[CHA 11] CHAVAGNEUX C., “L’instabilité du monde : Inégalités, finances, environnement. À propos de Suzanne Stange”, Ésprit, December 2011.

[CLE 08] CLERC P., “La culture au cœur des rapports de force économiques”, Diplomatie, Special edition, no. 5, 2008.

[CLE 11] CLERC P., “Intelligence économique et stratégies d’influence”, L’ENA hors les murs, no. 416, November 2011.

[CLE 15a] CLERC P., “Du soft power au smart power. Quelles stratégies d’influence ?”, Diplomatie, no. 24, 2015.

[CLE 15b] CLERC P., “Les enjeux informationnels des territoires” in C. HARBULOT (ed.), Manuel d’intelligence économique, Presses universitaires de France, Paris, 2015.

[DAV 02] D’AVENI R.A., Strategic Supremacy, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2002.

[DAV 12] D’AVENI R.A., Strategic Capitalism. The New Economic Strategy for Winning the Capitalist Cold War, McGraw Hill, New York, 2012.

[DEP 16] DEPRAZ S., “Économie sociale de marché ou économie verte de marché ? L’équilibre délicat de la durabilité territoriale allemande”, Bulletin de l’Association de géographes français, vol. 93, no. 1, pp. 3–25, 2016.

[DIR 16] DIRIDOLLOU C., DELECOLLE T., LOUSSAÏEF L. et al., “Légitimité des business models disruptifs : Le cas Uber”, La revue des sciences de gestion, vol. 5, nos 281/282, pp. 11–21, 2016.

[DOU 16] DOU H., “Influence, rumeur, intelligence économique et attractivité territoriale”, Réseau transméditerranéen de recherche en communication, XVIIe Forum international, Marseille, France, November 24–26, 2016.

[GRE 17] GRENOBLE ÉCOLE DE MANAGEMENT, Website, 2017, available at: http://www.grenoble-em.com/.

[HAB 87] HABERMAS J., FERRY J.-M., Théorie de l’agir communicationnel, vol. 2, Fayard, Paris, 1987.

[HAR 13] HARAPIAK C., “IKEA’s international expansion”, International Journal of Business Knowledge and Innovation in Practice, vol. 1, 2013.

[HUY 05] HUYGHE F.-B., Comprendre le pouvoir stratégique des médias, Eyrolles, Paris, 2005.

[HUY 11] HUYGUE F.-B., “Diplomatie publique, softpower… Influence d’État”, Observatoire géostratégique de l’information, July 5, 2011, http://www.iris-france.org/docs/kfm_docs/docs/2011-07-12-diplomatie-publique-softpower.pdf.

[KEO 98] KEOHANE R.-O., NYE J.-S. JR., “Power and interdependence in the information age”, Foreign Affairs, pp. 81–94, 1998.

[LAM 17] LAMY P., GNESOTTO N., BAER J.-M., Où va le monde ? Le marché ou la force ?, Odile Jacob, Paris, 2017.

[LER 08] LEROY F., Les stratégies de l’entreprise, Dunod, Paris, 2008.

[MEA 17] MEARSHEIMER J.-J., WALT S.-M., “Offshore balancing : Une stratégie globale plus efficace pour les États-Unis”, Revue internationale et stratégique, vol. 1, pp. 18–33, 2017.

[MOR 00] MORIN E., Les sept savoirs nécessaires à l’éducation du futur, Le Seuil, Paris, 2000.

[NYE 13] NYE J.S., “L’équilibre des puissances au XXIe siècle”, Géoéconomie, no. 65, pp. 19–29, 2013.

[POR 08] PORTER M.-E., “The five competitive forces that shape strategy”, Harvard Business Review, vol. 86, no. 1, pp. 25–40, 2008.

[POR 15] PORTER M., “Qu’est-ce que la stratégie ?”, Harvard Business Review, 2015.

[STR 15] STRANGE S., Casino Capitalism: With an Introduction by Matthew Watson, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2015.

[TUS 16] TUSSIE D., “Shaping the world beyond the ‘core’, in R. GERMAIN (ed.), Susan Strange and the Future of Global Political Economy: Power, Control and Transformation, Routledge, London, 2016.

[ZAI 13] ZAID M., TERGHINI S., “La notion de réflexion stratégique”, Studies and Research, vol. 5, no. 12, pp. 346–355, 2013.