10.1. Mental Models, Transitional Objects and Formal Models

The would-be racer's success (albeit limited) calls for a new or expanded definition of a model. A model is a tangible aid to imagination and learning, a transitional object to help people make better sense of a partly understood world. This definition focuses particular attention on the interaction that takes place between the model that someone carries in their head of the way something works (their mental model) and a formal model. To illustrate, consider a much different example provided by mathematician and computer scientist Seymour Papert 1980 in his remarkable book Mindstorms: Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas. He begins the book with an engaging personal recollection entitled 'The Gears of My Childhood', a story of how he came to better understand the working of complex sets of gears and ultimately abstract ideas in mathematics (p vi):

Before I was two years old Ihad developed an intense involvement with automobiles. The names of car parts made up a very substantial portion of my vocabulary: I was particularly proud knowing about the parts of the transmission system, the gearbox and most especially the differential. It was of course many years later before I understood how gears worked: but once I did, playing with gears became a favorite pastime. I loved rotating circular objects against one another in gearlike motions and naturally, my first 'erector set' project was a crude gear system.

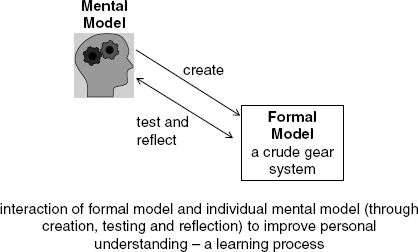

Figure 10.1 shows the role of the formal model (in this case a crude gear system) in a learning process. On the left is the child's mental model of a gear system depicted as gears in the mind. On the right is the formal model – a tangible set of gear parts that can be assembled, broken apart and re-assembled in lots of different ways. At the start, the child's mental model is primitive and naïve, but the activity of repeatedly playing with the gear set leads to a much more sophisticated understanding and deeper appreciation of gear-like motions. The mental model goes through a series of 'transitions' from naïve to more sophisticated through repeated use of the gear set as a transitional object. Papert (1980, p vi) fondly recalls his early learning experience:

Figure 10.1. Formal model as transitional object for individual learning – 'gears of childhood'

Source: From Systems Modelling – Theory and Practice, Edited by Mike Pidd, 2004, © John Wiley & Sons Limited. Reproduced with permission.

I became adept at turning wheels in my head and at making chains of cause and effect: 'This one turns this way so that must turn that way so ...' I found particular pleasure in such systems as the differential gear, which does not follow a simple linear chain of causality since the motion in the transmission shaft can be distributed in many different ways depending on what resistance they encounter. I remember quite vividly my excitement at discovering that a system could be lawful and completely comprehensible without being rigidly deterministic. I believe that working with differentials did more for my mathematical development than anything I was taught in elementary school. Gears, serving as models, carried many otherwise abstract ideas into my head.

(From the Foreword of Papert, S, 1980, Mindstorms: Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas. Basic Books, New York.)

Note that the definition of 'model-as-transitional-object' suggests a formal model achieves its value principally through creation and use. Moreover, tangibility is an important attribute of a transitional object somehow different from adequacy of representation. As Papert comments, gears serving as models not only enabled him to think more clearly about gear-like motion, but also to understand abstract ideas about mathematics.