3

TEACHING CULTURE SO

THAT OUR NEW HIRES

“GET IT”

Jessica was excited to overhaul the distribution processes at her new employer, Luccia Semiconductor.1 Jessica’s previous role as a senior logistics manager for one of the technology sector’s foremost supply chain innovators made her a highly touted recruit, and she was eager to showcase her skills. In her first four months at Luccia, Jessica had toured manufacturing and distribution facilities on three continents, dissected historical performance measures, and developed a series of process-change recommendations that were sure to impress. Her business case was airtight: She could save the company millions each quarter and cut distribution time by 30%.

Standing before her boss and a small group of supply chain VPs, Jessica confidently launched into her first presentation, which laid out her finely tuned process-improvement proposal. Five minutes in, she reached a slide that was sure to inspire the group to take action: A graph that quantified the wasteful spending plaguing the distribution function. It was at this point that something surprising happened. Jessica had just begun her detailed description of the group’s inefficiencies when her boss’s supervisor, the Logistics Vice President, Frederick Joseph, interrupted. “Jessica, let me help get us refocused. Thanks for raising this issue, but we have a full agenda today, and I think it would be a far better use of time for the whole group if you and I discussed your ideas later.”

Confused, Jessica sheepishly sat back down at the board table. Her boss pulled her aside after the meeting to discuss what had happened. “Fred has been with the company for 15 years. He practically built the logistics function from the ground up. Your presentation was spot on, but it called his management skills into question in front of the other VPs. That’s why he cut you off.”

Jessica was upset. She wasn’t boorish or untactful. In fact, she had long been noticed as someone who knew how to get along with others and collaborate productively. At a post-crisis meeting with her mentor, Jessica learned that she had misread her new organization’s culture. At her old company, the culture encouraged constructive debate, regardless of level or stature, and nobody felt like fingers were being pointed—it was the norm. The mantra “best idea wins” was plastered on the wall of every conference room of the manufacturing operations headquarters and at each facility. Jessica had mistakenly assumed that this same culture prevailed at Luccia. She had never even considered the possibility that the two organizations would possess such different cultures. Unfortunately, nobody had coached her about this. Now she had gotten an abrupt and disturbing wake-up call.

Jessica’s experience is hardly unique. For most new hires, understanding a new company’s culture is a difficult, nuanced, and gradual process. It’s also mystifying, since so much of the company culture remains under the radar. New hires learn about the culture through osmosis over the course of numerous interactions with other employees. Gaffes and miscues are the norm, leading to frustration and sub-par performance. Often a company’s professed culture taught during the initial orientation program doesn’t reflect realities on the ground so much as the culture desired by management (unlike Jessica’s previous employer, where the mantra was the culture). In other cases, companies do not spend much time at all orienting new hires to the culture, either formally or informally. This omission amounts to a huge error made by some of the greatest organizations. With adequate instruction, the manager can help prevent these gaffes in the first place, or at the very least, apply damage control for the new hire and turn the gaffe into a helpful learning experience. The sooner new hires understand the organization’s unwritten rules, the more risk we can take out of the system for them, and the more quickly they can make an impact and feel gratified by their contribution.

This chapter makes the case for teaching culture, and it offers instruction for how to do it effectively and systemically. We do not wish to stifle individuality or foster group-think (we abhor the word acculturate), but merely provide hires with proper insights so that they can make informed judgments about how to conduct themselves (acclimate works better for us). Firms seeking to improve retention, productivity, and other metrics as well as those seeking to transform their cultures and operating norms should work to convey an honest and deep understanding of culture to new hires. But what exactly does that mean? We offer best-in-class principles for transferring unspoken company norms to new hires in efficient and meaningful ways. Instruction from the CEO, structured mentoring encounters, simulated work experiences, hiring manager interventions, cohort support groups, wikis on the company intranet site, and many other tools can all serve to introduce new hires to reigning values, language, and practices. What is most important is that firms take time to understand the unspoken ways that business gets done in their organizations and implement a systemic approach for teaching it. Doing so improves the learning curve and helps reduce the painful outcomes for those who “don’t get it.”

Corporate and Organizational Cultures

Before we can appreciate the need to immerse new hires more fully in culture, we first need to consider what culture is ... and is not. United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously noted in a 1964 censorship case that “pornography is hard to define,” but “I know it when I see it.” The same can be said about culture. Sociologists and anthropologists have spilled much ink setting forth competing theories about what culture is. Business scholars have applied these theories, offering an important distinction between organizational culture and corporate culture. Roughly speaking, corporate culture is comprised of the values and traditions that derive from the mission and vision set by a company’s leaders and make the firm unique in the eyes of management, employees, and the marketplace. Organizational culture includes corporate culture but is broader, also reflecting how people in any organization actually think and behave, perhaps unconsciously.

When managers refer to culture, they often talk more narrowly about consciously articulated corporate culture. Many firms take pride in their heritage and spend a fair amount of energy communicating their history to new hires. Yet heritage and an articulated sense of corporate culture aren’t always as relevant operationally as leaders might think. No matter how aware one becomes of their organization’s corporate heritage, they are still operating in the complexity and the dynamism of the here and now. If you compare your corporate heritage with how your organization actually functions, you will find you have two different animals. Corporate cultural elements that have allowed for success in the past, or that correspond to an idealistic sense of what sets your organization apart, are likely not to help your employees succeed right now or help your organization perform at its best.

In speaking of culture, then, we refer to the broader organizational culture that arises out of how people actually come together to get work done (and in the case of dysfunctional cultures, avoid getting work done). We especially like MIT Professor Edgar Schein’s notion of organizational culture:

A pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration, that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way you perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.

By this definition, a unifying culture emerges naturally over time in the course of the organization’s actual functioning. It is a “set of assumptions” about the world that are tried and true and are passed on to new members as established norms. Because organizational culture also includes within it the formally articulated corporate culture, we also need to consider the stated values that people working together maintain. Finally, we need to consider observable artifacts—the language, symbols, style, and behaviors—that shape workplace experience.

When we think more closely about Schein’s definition of organizational culture, we begin to see how treacherous culture can be and why new hires often get caught up in cultural snafus. Members of an organization might consider the common assumptions of a culture to be “valid,” and they might impart them to new members. But even some company veterans may not necessarily be aware of these assumptions, let alone the skills necessary to distill and communicate them. They thus fall back on unconsciously communicating social norms in the course of attending to regular business. In the absence of explicit instruction, new hires do not learn about culture as efficiently or unambiguously as they otherwise might. Meanwhile, new hires have trouble teaching themselves because of something we coined the Irony of Norms. The Irony of Norms says that social norms by their very definition remain invisible, and only violations of the norm stick out and actually get noticed, not the norms themselves. Because new hires tend to depart from the norm, it is (ironically) their behavior, and not the organization’s, that runs the greatest risk of sticking out. Therefore, new hires find themselves dog-paddling through the new culture, not sure where to go, making their way as best they can.

Many companies convey shared values as part of their mission statement and in the course of delivering performance reviews or mentoring. Yet in general, the discussion stays at a high level, the firm communicating hazy, feel-good values (e.g., “we value diversity”). Language like this attempts to present a sharp corporate culture, yet it does not do much to convey the realities of organizational culture. New hires are left to glean organizational norms from dress or ethical codes, expense reimbursement rules, and other policies. This is an inefficient and frustrating way to learn. An organization’s attitude about technology adoption, for instance, often is not directly communicated; instead, it comes through in the way a new hire is given information, the devices he or she is given, rules provided around the use of technology, or the absence of these things.

Performance Values

Schein’s definition also helps us because it suggests why culture is inherently relevant, even vital for both new hires and organizations. Specific elements of organizational culture emerge and are passed on because “they’ve worked well” over time. These elements amount to unspoken assumptions about which problem-solving approaches have allowed the firm to adapt to external conditions and thus will likely do so in the future. In the context of an employee’s experience, these elements take on life as unwritten performance values, i.e., things that the organization believes make for a great employee. Organizations judge an employee’s performance and prospects according to how well he or she embodies accepted performance values. One company might posses a culture that features vigorous open debate as a performance value, whereas another might value quiet consensus building behind the scenes. At both firms, this dimension of culture helps determine whether an individual’s job performance comes across as strong or weak. Clearly everyone benefits if new hires understand exactly what these performance values are.

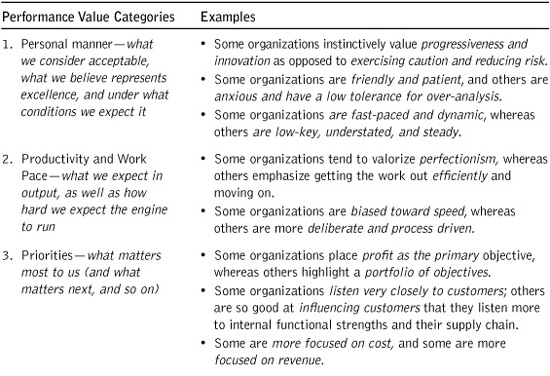

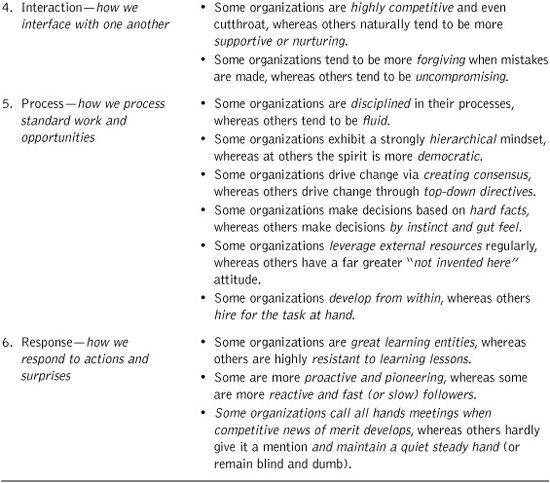

Table 3.1 Organizational Performance Values

In thinking about performance values, we can break them down into the six categories outlined in Table 3.1 on the previous page.

Our clients offer a number of common responses when we show them Table 3.1. They note that our list of sample performance values is far from complete. Many times organizations do not line up at the extreme end for any given performance value, but hover in a murky territory in between. Performance values are constantly shifting and evolving. And certain attributes are far easier to discern in some organizations than others. Clients also point out that many of the performance values we discuss are subject to interpretation. One new hire might conclude after a discussion with his boss that the company is “hierarchical,” “slow,” and “political,” whereas another might just as reasonably conclude that the company is “careful” and “has strong processes” and “checks and balances.” Finally, clients remark that no organization is comprehensively any one thing as it relates to distilling culture. Although an attribute may largely describe an organization, some parts of the organization might diverge from the norm. What may hold true for one work group may not apply to the larger division, nor the whole business unit or corporation.

The New Hire’s Perspective

Often, cultural norms at companies are inherently elusive, ill-communicated, or implicitly transmitted; and these cultural norms directly inform judgments about performance. It’s safe to say that new hires face quite a challenge indeed. Let’s imagine the trepidation a new hire must feel when he or she first comes onboard. In fact, there is no need to imagine it—we’ve all been there. We have all been thrust into a new environment that is much different from what we are used to but in ways we can only partially grasp. Lacking deliberate instruction in a firm’s implicit code or language, we’re left floundering on our own, coming up with a fuzzy sense of the rules from what little data we have.

Learning the lingo

Workplace slang offers a great example. Each workplace and industry has its own unique vocabulary that has developed over time and through shared experience. When you start at Procter & Gamble, you need to figure out what acronyms like SMOT (Second Moment of Truth; i.e., the moment when a customer uses and judges their product), GBU (Global Business Unit), or XFS (Cross Functional Solutions) mean (a full 34% of Procter & Gamble’s search activity on internal corporate networks are for acronyms).2 FedEx Office’s workers need to understand what the firm’s “purple promise” is (shorthand for the firm’s commitment “to make every customer experience outstanding”). Army clients we’ve worked with use slang that is quite funny at first to outsiders, asking questions like, “Who is the belly button (i.e., the person in charge) on the issue?” or “What does it look like from your foxhole?” At Accenture, employees track billable hours by “entering it into ARTES,” whereas at Booz Allen Hamilton it’s “entering my TOL.” At all organizations, being able to “speak the language” builds confidence and shows that you are a part of the firm—an insider.

We hear so many reports of new hires struggling to learn the lingo. Some companies provide dictionaries, but nine out of ten times we find that the dictionary simply provides technical definitions (e.g., spelling out the acronyms). They hardly ever instruct new hires as to the deeper meaning, origins, and evolution of key words, nor do they provide an explanation for why they remain so central. By failing to help new hires understand vocabulary to the fullest, you are missing a huge opportunity to fill in the blanks and teach what really makes the organization tick. In the case of the professional service firms we have noted, the language used to reference the time entry systems speaks directly to the firms’ core business model and how they drive profitability. By bringing forward these definitions, the company can meaningfully discuss the business model and supporting management structure that contributes to the company’s success.

Major issues the new hire faces

New hires might hope that the few days or week of orientation help them wrap their heads around slang and the many other informal elements of company culture, but it doesn’t usually work that way. In the ensuing days and weeks, they are left to fend for themselves in negotiating a number of daily questions big and small. Some of the major things they are anxiously trying to figure out include:

• Informal ways colleagues make decisions: What gives people “permission” to decide on an issue? Is it their ability to muster facts? Is it the boss’ approval? The inherent authority that comes with their job? A combination?

• Communication styles: Does the hire’s new workplace like the one-page memo? The PowerPoint deck? Three bullets? Casual conversations in the hall? Do people like to gain information on a need-to-know basis, or is an open communication more efficient and therefore desirable? And again, the language: What do casual words and phrases really mean?

• Idea advocacy: Does the organization prefer a structured or formal process for bringing forward ideas—e.g., using templates and a defined process and forums—or does a culture of open brainstorming reign? Do ideas need vetting before expression in an open forum, or do colleagues feel comfortable with a new hire just bringing something up?

• Who’s who: Who is important to company decision making? Who do I need to impress? With whom do I need to develop a good working relationship so as to successfully partner on work assignments? How do the leaders’ styles differ?

• Dispute moderation: Some organizations designate people and processes to address and formally moderate disputes when they arise, whereas others encourage colleagues to moderate disputes themselves. What’s the rule here?

• Managing up: Is the hire’s new culture hell-bent on micro-managing? Does he or she have to keep superiors constantly updated on progress? Is there a consistent standard, or are there certain scenarios in which superiors require a higher communication standard? Is the weekly or monthly check-in sufficient? And how does the new hire keep people informed? Through water-cooler chats? A formal scheduled meeting? An online template? Or emails on an exception-only basis?

• Appropriate conduct: What is the right time, place, and means to do anything?

Negotiating these issues—and again, this is only a partial list—takes time and energy, detracting from new hires’ ability to become effective at their jobs as quickly as they would otherwise, and reducing their engagement. It’s an intimidating process for new hires, since they are trying to impress their new colleagues, yet they sense that these colleagues are already evaluating them on the basis of norms that are puzzling and only partially revealed. Think of how frustrating, let alone unproductive, the following situation would be:

At your last job you had grown accustomed to the standard of approaching business challenges by examining first and foremost what the competition was doing, how they respond to customer needs, and how they might respond to your firm’s actions. In contrast, your new company has an internal focus, but no one took the time to highlight this fact for you. Being conditioned for eight years at your prior firm, you are probably thinking and taking actions that are not in concert with your colleagues and your reporting manager. You seem not to make any headway in your job, and for a while at least, you are not sure why. You think you’re doing everything right, and then your manager informs you that in this first 6 months he found that your thinking is “frustratingly off.” If you decide to go against the grain, you won’t even necessarily know how to do that well; you will be clueless about which battles to fight, how to fight them, and whom to choose as your allies and enemies.

Leaders in your new culture might negotiate decisions casually over lunch rather than during a formal meeting. Choosing one over the other can make all the difference, and when you get it wrong early in your tenure with new employers, it is not fun for you or them.

Other factors and situations can render new hires’ frustration especially pronounced. If you’re already experienced with other cultures or are new to an industry you come in with ingrained habits and attitudes that might conflict strongly with your new organizational culture. In the early 1980s, John Sculley transitioned from President of PepsiCo to CEO of Apple Computer. Scully had grown famous in his old job for being a “marketing guy,” the executive who had successfully introduced the “Pepsi Challenge” and won share from Coca-Cola, a challenge deemed similar to Apple’s need to win share from Wintel (Microsoft Windows- and Intel-based personal computers). Upon entry to Apple, Sculley needed acclimation into at least three distinct and new cultures—that of the personal computer industry, Apple, and finally the Silicon Valley tech community. Think about how challenging it must have been for an accomplished leader familiar with Pepsi’s process and data-driven culture to encounter the entrepreneurial, personality-driven world of Silicon Valley for the first time. In fact, it was too challenging. As Wired magazine summarized the shift, “the suave East Coast marketing executive ... took for himself the mantle of Apple’s visionary leader. Nearly everyone pretended not to notice how badly it fit.”3

If new hires do not enter a firm with ingrained habits, sometimes they come brimming with positive and potentially unrealistic expectations about the culture, only to become disappointed when these expectations don’t pan out. Such disappointment often occurs when the organizational culture a new hire enters breaks from a well-known consumer brand associated with the company. A high-end luxury company, for instance, might convey in its advertisements the very epitome of sophistication, elegance, and extravagance. Show up at its corporate headquarters as a new hire, and you might discover evidence of a very different internal culture and associated performance values. The office furniture is dated, employees come dressed casually, and mid-level employees operate in a bit of a frenzy. In short, everything about the place seems unrefined and decidedly inelegant. If you came to work thinking that every day would be “special,” you would be in for a rude awakening.

In this case (involving a real-life company, by the way), important aspects of the organizational culture are at least immediately visible. Organizations such as IDEO, Nike, Best Buy, Bloomberg, and The White House possess visually unique work environments that create an impression of the culture. The vast majority of workplaces, however, are visually every bit as generic as that portrayed in the television show The Office. Consider how much more puzzling these workplaces are for new hires. Even if you don’t come in primed for a certain culture, you still find that your most important sense—vision—offers little help in deciphering the world of work you’ve just entered. As a designer of your company’s onboarding system (or a hiring manager), you need to consider whether your new hires are entering with false impressions of your brand that have been affected by the consumer brand or other influencing factors, such as significant moments in a company’s history that have developed into nearly mythical status.

New hires notice contradictions

Entering hires also have their new company’s often-unrealistic portrayal of its organizational culture with which to contend. To the extent that companies talk about organizational culture with new hires, they often make matters worse by downplaying negative aspects of the culture or even outright ignoring them in the course of presenting what is really their aspiration for the culture. As consultants, we walk into the most admired companies, those that make fantastic products that have changed the world and created immense wealth, and we find that the people who work for these companies—including their leaders—commonly lament about “how screwed up we are.” We hear this all the time. New hires are especially primed to discover the flaws in culture, because they’re put into vulnerable positions that encourage defensive reactions on their part. When management comes along with lofty and ultimately quite meaningless rhetoric about how noble the firm is, they create an unpleasant experience of cognitive dissonance. New hires are told the firm values innovation, yet upon offering a suggestion they are informed in a condescending tone that “we don’t do it that way.” They were told the firm values collaboration, yet they have just sat through a meeting in which two functional managers squabbled over who owned a certain process.

Left unresolved, as is so often the case, such contradictions can cause new hires to become increasingly cynical and distanced from firms they initially might have been quite excited about joining. It gets worse from there. New hires are smart, sensitive people who commiserate with other new hires. They wallow together in complaints and negativity. Instead of the excessively positive image of the organizational culture the firm intended, new hires feed on the frustrations of those around them, discovering more and more about the culture they had not noticed and do not like. Imagine what this does for the firm’s energy level, productivity, and talent retention.

This is what new hires often experience when they encounter unspoken norms in a new organizational culture. It is not a pretty picture—not for the new hire, and certainly not for the firm. Yet the large majority of managers take a defeatist stance and do nothing. They assume that acclimating to new organizational cultures is difficult by definition. They think that new hires and companies alike need to buck up; that companies just have to accept a period of lower productivity as new hires get up to speed, as well as tolerate a certain amount of attrition. However, this just isn’t true. Although no onboarding program can give new hires a perfect and instant sense of familiarity and ease, an effective program can and should make the acclimation process much easier. What if we put systems in place to communicate unspoken norms to hires? What if we engage in an ongoing, progressive dialogue about organizational cultures, revealing them honestly, flaws and all? What if we exposed hires over time to the nitty-gritty of our performance values, offering explanations about why they exist and advice for how to perform in line with these values? Mark our words: When these initiatives are implemented, performance rises.

New Hires and Onboarding as a Lever to Drive Change

If nurturing happier, more productive, more engaged, and more committed new hires is not reason enough to include cultural education in a strategic onboarding program, consider this: Structured cultural education can also play an important role in helping an organization support new strategic initiatives.

Transformational strategies do not exist in vacuums. Executing them properly means addressing organizations’ daily functioning and experience, and specifically, helping our workforces to develop new skills, processes, and habits. A wonderful illustration of this appeared in the classic Christmas movie Miracle on 34th Street, which portrays the competition between two retail stores, Macy’s and Gimbels. A Santa Claus hired by Macy’s for the holiday season delights customers by referring them to other stores when Macy’s own merchandise doesn’t fit their needs. In a lesson to any modern-day retailer who seeks to become more customer-centric, Macy’s starts to infuse the practice of referring customers to the competition throughout its workforce, and in response so does Gimbels. Employees deliberately cultivate new skills and capacities, such as an awareness of customer needs and desires and extensive knowledge about the offers available at other stores. Contrary to Hollywood depictions of it, the transformation of employee behavior in real life does not always happen right away. But of great import for the conception of your onboarding initiative—unlike veteran employees, new hires actually represent an easier group of employees to adapt to the new company direction and can be a great lever to drive organizational transformation.

If true organizational transformation reaches deep into the daily life of a workplace, it is not enough for firms to take a one-off or haphazard approach to cultural change. In a recent Harvard Business Review article entitled “Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail,” noted management thinker John Kotter cited eight common errors, including “not anchoring changes in the corporation’s culture.”4 As Kotter relates, the firm must make repeated efforts to “show people how the new approaches, behaviors, and attitudes have helped improve performance.” Doing this might involve taking time out at every meeting to assess why performance was improving or running articles in a company newspaper linking performance and cultural change. At Home Depot, cultural change in the early 2000s actually went well beyond these techniques, including the establishment of five-day learning sessions for almost 2,000 district and store managers at the retail chain. The firm has also institutionalized the new culture by offering ongoing training programs, including its Future Leaders Program.5

Given that the average large organization renews as much as 30% of its workforce in three years (12% attrition gets you there pretty quick), formally enrolling new hires in the organization’s change efforts can prove an immense help in getting the job done. To understand what enrolling new hires in change might mean, just think of General Electric. For a 15+year period, the company’s entire operating strategy centered on a six-sigma initiative to drive continuous improvement, elimination of waste, and quarter-to-quarter earnings improvement. By the late 1990s, the culture found itself in a difficult position when six-sigma began delivering diminishing returns. The company became more and more reliant on a single operating unit—GE Finance—to deliver enterprise-wide financial returns, which itself began to stress. In 2000, with the appointment of CEO Jeff Immelt, the company began to remake itself as an innovation leader. Instead of finding marginal gains from existing businesses, GE would need to discover new customer needs and enter emerging industries. You can imagine the degree to which a behemoth like GE, formerly so focused on operational excellence, needed to transform its culture to meet this new leadership mandate. Given the length of time this transformation would take, GE clearly had an opportunity to capitalize on turnover in its workforce to bring in personnel who would prove even more amenable to embrace the new culture than existing employees, who were conditioned to the old culture.

How Robert W. Baird Does It

The Milwaukee-based financial services firm of Robert W. Baird & Co., Inc. has made great strides in leveraging the onboarding of new associates to drive change. In the case of its Private Wealth Management business division, Baird has used new hires as a key lever in driving a cultural as well as business model change.

Baird’s Private Wealth Management (PWM) business division serves the financial needs of individuals, families, executives and businesses through 70 branch offices across the United States. Until 2002, Baird served their high net worth clients much like other investment firms, with individual Financial Advisors bringing forth investment solutions to meet their client needs. In 2002, Baird shifted toward a team-based approach, whereby Financial Advisors with complementary strengths work together to best address the myriad financial issues of higher net worth families and individuals.

In recent years, many financial services firms have begun to support the formation and development of financial advisor teams, but few firms provide the solid foundation and framework for teaming like Baird does. While a team approach is strongly encouraged by Baird’s Executive Management Team, veteran Financial Advisors are not required to join or form teams. However, the organization does require new, non-veteran Financial Advisors to join or form a team before their hire process can be completed. This is a very unique approach in the industry, but one that boasts big payoffs as Baird’s non-veteran Financial Advisors success rate after five years is 65% versus industry standards of 15%.

The process for onboarding new, non-veteran Financial Advisors (titled Financial Advisor Associates or FAA until graduation) is a long and rigorous process. Each FAA is required to complete 5½ months of training, pairing products and services education with professional development at the team level. Phase I of the four-phase program focuses on Series 7, Series 66, and Life & Insurance licensing. Phase II includes 33 curriculum modules to ensure each FAA has a broad and deep understanding of the solutions offered and supported by Baird. Phase III is a two-week phase during which all FAAs are required to participate in training at Milwaukee headquarters. In addition to participating in roles plays, case studies, and technology demonstrations, team members are also required to join their FAAs for a two-day instrumental business planning workshop. The final phase of the program, Phase IV, requires each FAA to present their team’s formal, comprehensive business plan to a panel of representatives from Sales Management, Talent & Development, business coaches and veteran Financial Advisors. This presentation establishes the FAAs role on their newly established team and brings them to the final component of onboarding—graduation with CEO & President Paul Purcell.

Throughout the new hire onboarding and teaming processes, Branch Managers who oversee Baird’s PWM branches, play critical roles. They are responsible for the profitability of the branch network and are thereby incentivized to do what they can to coach their new teams and advisors. The entire process is supported by a team of specialists in Human Capital, Products & Services, Compliance, Legal Services, Marketing & Communications and many more areas of Baird’s Corporate Resource Groups. By involving key stakeholders from across the organization, this approach is intended to enhance the likelihood of new advisor and new team successes. Evidenced by their success rate of new associates being about four times greater than the industry average, it looks like the PWM division of Baird is achieving its goal.

The enrollment of new associates into the team structure at the onset of onboarding has been a key contributor to helping to institutionalize the team-based approach as part of Baird’s culture and successful business model.

Getting Started: The Cultural Audit

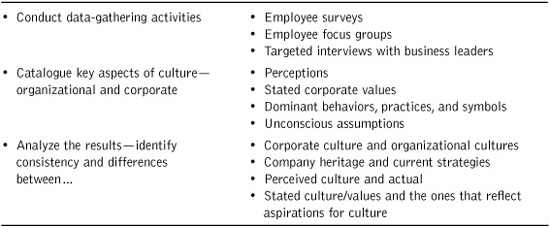

We have examined how important it is for firms to include cultural conversations as part of strategic onboarding programs. Now it is time to discuss how to do it. Before firms can begin to develop a formal way of engaging new hires on the topic of organizational culture, management first needs to become aware of its organizational culture. We advise that managers begin by reaching across silos and performing a formal cultural audit. This exercise entails a cataloguing and analysis of all aspects of culture—the unconscious assumptions, the stated corporate values, and dominant behaviors, practices, and symbols. The exercise also includes the identification of perceptions about the culture, including any dominant myths that employees might have. If you are embarking on an onboarding redesign effort, the cultural audit will be conducted as one element of the diagnostic effort in your initiative (which is discussed in detail in Chapter 8). However, as a short preview, consider the Cultural Audit activities listed in Table 3.2. Depending on the depth of understanding of the current state that you begin with and the level of resources that will be dedicated to conducting the audit, you may incorporate some mix of these activities, but not necessarily all of them.

An audit can prove especially valuable if it uncovers practices that lead to identification of undesirable perceptions or rumors about the culture. At one of the firms with which we work, a perception had quietly taken hold that golf was a vital part of the organizational culture, especially at the top echelons. Certain executives, including a number of women, felt left out, since they weren’t especially enamored with golf. They even came to believe that their lack of enthusiasm toward golf would impede their careers, as they simply felt sidelined in too many conversations. In fact, this perception was overblown. Senior managers of this company had many other interests besides golf, and the last three big promotions had gone to individuals who had never stepped foot on a golf course. By uncovering such misconceptions, a cultural audit enables the onboarding designer to either dispel them or instruct the new hires how to negotiate a cultural terrain that might cause them discomfort—before resentments arise, productivity falls, and people leave.

Table 3.2 Cultural Audit Key Activities

Cultural audits also provide an opportunity to discover any discord between a firm’s visual culture and its organizational culture. At Nike’s corporate headquarters, managers want employees to think like its consumers, so a visual culture of athletic performance reigns. The buildings are constructed as shrines to athletes, employees walk about in casual athletic clothing, and the campus includes a great number of specialized running tracks and athletic fields. If Nike’s deeper organizational culture is one of severe competition resembling athletic performance—if the best answer wins and we don’t attend to the losing ideas except to learn lessons from them—then the physical culture and organizational culture align. But if not, then some employees are going to feel confused. A cultural audit would alert Nike to the need to educate new hires as to the differences between the layers of culture they would encounter if this discord existed.

Finally, cultural audits are helpful because they afford managers a chance to discover any disconnect between the firm’s stated corporate culture and the strategies they are attempting to implement. Heritage and tradition are vitally important to sustain, yet a firm’s stated values cannot remain stagnant over time; survival requires at least some evolution and adaptation. Senior leadership needs to question whether implicit, unspoken norms should change to meet strategic imperatives. We suggest that senior leaders evaluate and update the cultural audit together on an annual basis, analyzing what kind of cultural change the company must pursue to support the strategy as well as how the firm can use new hires to drive cultural change. Middle managers should also participate in these yearly “cultural summits,” as they are typically the ones in an organization who translate strategy to boots-on-the-ground action.

You may have your own personal opinions as to which performance values organizations should emphasize to sustain a healthy culture. In the context of onboarding, however, judging specific performance values misses the point and actually causes managers to fall into a trap. In trying to communicate culture, many managers use the exercise as an opportunity to try to change their company’s culture for the better. Clearly, improving culture is commendable and most certainly part of a manager’s role. Yet as we’ve suggested, managers err when they fail to distinguish performance value aspirations from real ones currently in operation. Both the real and ideal can be communicated, so long as they are distinguished from one another. Otherwise we are only setting new hires up for confusion and poor performance.

Framing Messages about Culture

Once designers understand what their organizational cultures are about, the next step in developing a strong cultural component to onboarding is framing an appropriate educational message. Perhaps the most important principle to follow is a simple one: Honesty. Do not take a sales or advertising approach in communicating culture to employees. Speak openly about the “true culture” so employees can get a sense of what their actual experience will be on the job or can validate what they have experienced of the culture so far. Firms should even strive to point out existing shortcomings in the culture, the reasons these shortcomings exist, and the efforts the organization is making to bring about change.

One company that does a great job of presenting an apparently honest portrait of its own culture is Netflix. Posted on the company’s web site is a 128-page PowerPoint presentation on company culture in which the CEO and founder Reed Hastings himself introduces the firm’s culture in an open, honest, and engaging way. The presentation opens by observing that “lots of companies have nice sounding values statements,” including Enron, whose stated values of “integrity, communication, respect, and excellence” were engraved in marble in the main lobby. However, given Enron’s demise, these words “had little to do with the real values of the organization.” The presentation then lays out in clear language Netflix’s nine values: Judgment, Communication, Impact, Curiosity, Innovation, Courage, Passion, Honesty, and Selflessness.

Here is where some firms might stop, but Netflix’s presentation does not. After describing the nine corporate values, Netflix’s CEO goes on to outline seven other “aspects of our culture,” some of which—“high performance, freedom and responsibility, context not control, highly aligned, loosely coupled”—are essentially performance values. Under “high performance,” for instance, the CEO outlines Netflix’s assumption that every employee will be a “star” in his or her position, or they won’t work here (how is that for frank talk?). As part of this performance value, the firm promotes honest assessments of performance, counseling new hires to collect frank feedback: “To avoid surprises, you should periodically ask your manager: ‘If I told you I were leaving, how hard would you work to change my mind to stay at Netflix?’” The CEO also goes on to explain his business rationale for valuing all-star performance above things like hard work or loyalty, arguing that in creative work such as that performed by Netflix’s workers, high-performing colleagues are “ten times more effective than the average employee—a far greater spread than in procedural work.” High performance workers have an especially big impact, which is why the firm is “so manic on high performance.”

We are not endorsing Netflix’s opinions or values per se. What is more important is how clearly Netflix communicates what it expects from new hires. The Netflix example suggests a few “best principles” of onboarding messaging as it relates to culture. To achieve maximum impact, designers of an onboarding program should not merely communicate the unvarnished truth about their cultures and firm performance values; there is more. To this end, we have our own list of ten best principles. These should serve as guidelines as you begin to design your onboarding program and its inherent message. Here are our first four best principles:

Best Principle #1: Use simple language that new hires can understand.

Best Principle #2: Go beyond lofty rhetoric to provide specific examples of how the performance values might play out in everyday life.

Best Principle #3: Make some effort to explain the business rationale behind the values.

Best Principle #4: Express the culture in passionate terms while also invoking the authority of company leadership.

The carefully designed welcome box Apple gives to all new hires before their start dates contains a short, clear, and inspirational statement of what the firm values and doesn’t value in the performance of new hires. It is so effective that we’ll let it speak for itself:

“There’s work and there’s your life’s work. The kind of work that has your fingerprints all over it. The kind of work that you’d never compromise on. That you’d sacrifice a weekend for. You can do that kind of work at Apple. People don’t come here to play it safe. They come here to swim in the deep end. They want their work to add up to something. Something Big. Something that couldn’t happen anywhere else.”

This statement is a very big motivator. Does it excite the workforce and affect the Onboarding Margin? You bet it does!

To provide further evidence of this point, our capture of this story was not from Apple. Rather it was from a new hire who proudly posted photographs and verbatims of his welcome kit on his personal blog. He was so moved by this message that he wanted to share with his community. His blog received great comments of endorsement from friends and admirers. His new employer had already begun (even before Day One) to move this new hire up Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs pyramid (see Chapter 1).

The key, ultimately, is to take new hires beyond the veneer of established and unspoken norms in a way that does not dumb down the organizational culture or evade its full complexity. We cannot just say that our company is forgiving or unforgiving. Organizations are uneven, so of course they will be forgiving in some ways and unforgiving in others. For instance, our firm might want to convey that the accounts payable is unforgiving in its rules for out-of-pocket expense reimbursements, but that if a manager took on a risky initiative and it didn’t work out, we’d be very forgiving. By using simple language, going out of their way to identify areas of distinction, and citing specific examples, as the Netflix presentation does, well-designed onboarding programs can give new hires a deeper experience of this complexity without eliciting confusion. As for the third principle, new hires will not only understand a cultural norm, but also assimilate and believe in its wisdom if they can understand an underlying rationale for its existence. When Netflix’s CEO provides productivity data about work, he isn’t just teaching organizational values, he’s going out of his way to explain the wisdom of the values. That is how you get buy-in.

In advising specificity, we emphasize that firms need to be smart. You cannot dump everything about an organizational culture on new hires all at once, which is another reason why programs should unfold over an entire year after a new hire comes onboard. Just as important, the onboarding designer has to figure out which elements of culture are important to understand, and which ones new hires can figure out on their own. It might not be as important to teach new hires about expense reimbursements in detail, since they will learn it naturally and it is quite honestly not all that significant. Yet it would be important to explain to new hires how people in the organizational culture are used to receiving criticism or negative feedback. In designing a cultural component to onboarding, managers need to identify and prioritize the mission critical components of culture. Let’s ask ourselves, if we really want to move the needle on our organization, what cultural knowledge will help us do that?

Here is an approach that we like to use when developing messaging for new hires. Instead of using phrases like “We’re great because....,” use phrases like “We’re at our best when....” Telling people why we are great does little to acknowledge limits or weaknesses in our organizational cultures. Instead, it causes a skeptical workforce (we hire smart, inquisitive people after all, right?) to question the credibility of the statements. It also does nothing to challenge the new hires. The company is apparently already “great,” and as a result is seemingly not striving to become anything else beyond what it already is. By contrast, “We’re at our best when ...” conveys that the company can achieve strong performance, but there are also times when the organizational culture does not work so well. It is a humbler and more realistic statement, and on that account, a more inspiring one. As a caveat to what we’ve been advising, companies can be inspirational, so long as they do not go too far. As part of this exercise, try creating some pairs of contrasting “We’re great because ...” and “We’re at our best when” statements for your organization. Try to make the “We’re at our best when ...” list as specific and descriptive as possible. Here are some contrasting statements we’ve created for an aerospace and defense firm and a consumer electronics company.

“We’re at our best when we collaboratively create a solution that addresses a well-defined, incredibly hard customer engineering problem.”

vs.

“We’re great because we collaborate across lines of business to solve hard customer problems.”

“We’re at our best when we’re not limiting our solutions to things we do ourselves, but bringing in external partners to serve customer needs.”

vs.

“We’re great because we bring best of breed solutions to the market.”

Consumer Electronics Company

“We are at our best when global management is having a two-way dialogue with local markets rather than dictating top-down.”

vs.

“We’re great because global leadership has a two-way dialogue with local markets.”

“We’re at our best when we understand the perspectives and realities of our partners’ businesses.”

vs.

“We’re great because we don’t impose the ‘our way’ on our partners.”

As a final word of advice for designing acculturation messaging, we want to stress the importance of customizing to different segments of employees. New hires require slightly different support depending upon where they are in their careers, where they work in the business, etc. If you have a limited budget, we advise spending more of the development and delivery budget on acclimating more experienced hires. Although this may at first sound counterintuitive, our research has found that on a relative basis, acclimation tends to be far easier for more junior employees. Why? For starters, they typically enter as part of a group of new hires, and cohorts tend to support one another navigating the new culture. Second, junior employees tend to possess fewer cultural biases on account of their limited experience. Finally, junior employees are typically acutely aware of how foreign the work environment actually is (because of their lack of confidence); as a result, they apply more energy to observing and learning the culture—they prove to be more tuned into the activity. More experienced hires enter with habits formed at prior work environments with different cultural norms, and they are also more confident and often less self-aware. Senior hires are also watched more closely, expectations are higher, and people are less forgiving. Senior hires thus need messaging that speaks about the firm’s organizational culture more sharply and comparatively. And they need support structures (e.g., mentors) to play a more important protective and advisory role.

Developing a world-class cultural component to an onboarding program requires not merely the right message, but a coherent, systemic approach to delivering that message. Earlier, we cautioned managers against the urge to take some generic “best practices” and apply that to their own firms. What worked for one firm might not work for another. Here again, we don’t offer specific suggestions, but rather the second batch of “best principles” to help guide you in developing the right tactics for use in designing your own customized onboarding program.

Best Principle #5: Make it interactive.

Culture is vague and hard to distill. For new hires to assimilate it and make it their own, they need to engage with it personally and creatively. A number of mechanisms allow for a more interactive experience of culture. One-on-one mentoring is critical. Firms should solidify the mentoring that already takes place with the following measures: establishing best practices, deploying the mechanism widely, offering clear guidelines and discussion points—specific to the new hire experience—for mentors to follow, and offering opportunities to assess employees’ cultural learning. Firms might also consider implementing a peer “buddy” program for new hires, teaming them with a slightly more experienced employee who possesses similar job responsibilities. This more experienced employee would serve as a resource for the new hire, helping him or her understand what the more experienced employee wished he or she had known upon first starting with the company, and serving as a safe person to consult when the new hire wishes to understand the lay of the land. In both cases, the mentor and peer buddy needs to have this responsibility as a formal part of the job description, and performance against the task should be measured and factored into annual assessments. Another technique we like is the new hire summit: Bring back the new hire class or cohort together periodically over the first year, perhaps at the six-, eight-, and 12-month marks, for interactive workshops about the firm’s unwritten rules (among other educational and directive content). New hires have a chance to reconnect and share their experiences, allowing for collective learning about the culture. Firms might also incorporate into the first week orientation a panel staffed by recent new hires that discusses what people wish they had known when they started.

Best Principle #6: Interactive technology is better.

Technology can make a difference. Wikis located on central intranet portals enable new hires (especially younger ones and those who work off-site) to distill unwritten cultural rules efficiently and collaboratively in a less formal environment. In this instance, new hires can post what they are seeing as the unwritten rules and other aspects of culture and performance as they experience them. The collective group then has rights to modify the cultural assessments, resulting in a community assessment of the culture, which in turn validates or dispels the perceptions that are being formed. If you deploy this kind of community approach to capturing culture, you need to give the community the same guidance that you would consider when outlining culture. Wikis, blogs (as long as they are interactive and anonymous), and related tools allow new hires to experience culture in a fun, less structured, and more authentic way without the constant circulation of an approved HR definition of culture.

General Mills provides streaming television content through its Champions TV channel, offering cultural programs, social announcements, and corporate information. The company also has an email-based daily newspaper that informs employees about upcoming events, group announcements, and relevant news about General Mills and the industry as a whole. As one new hire remarked, “Thanks to the newspaper I know what’s going on at both the wider company as well as in the market as a whole, which is pretty cool. It makes me feel like I’m part of something bigger than my department.” But be careful not to deploy a one-way communication system that comes off as corporate indoctrination and programming—employees today are too smart and too skeptical. Before you can blink an eye, they’ll write you off as inauthentic and the message as irrelevant.

Best Principle #7: Reinforce the message and make context relevant.

Firms should use a variety of media, venues, and circumstances to reinforce the education. For instance, the firm could provide on-demand messages on the intranet, broadcasts played at the beginning of a training session, messages posted centrally within company buildings, and a one-on-one mentoring program that reinforces all of this correspondence. Repetition helps people assimilate the cultural knowledge better than a more intense, single blast of communication can. And this leads to a related point: Cultural discussions, like other components of an onboarding program, require a gradual approach.

At the front end, firms might focus new hires’ attention via a more intensive, multi-day orientation. This should be followed during the year by other elements, such as the new hire summit and ongoing cultural mentoring. Hiring managers must also address their teams’ own local subcultures and communicate them over time. Whenever a manager starts a new project, whenever he or she starts a “first,” the manager needs to take some time to provide guidance around the culture and performance values. Hiring managers should also take care to step in when people are doing things wrong in relation to the culture. It is often helpful for a hiring manager to sit down early on with the new hire and investigate what his or her old culture was like. This conversation should be guided by a standard template and guidebook. Six months later, hiring managers can talk about the culture again, doing a “pulse check” now that the new hire has more context for understanding the culture. During the annual review, hiring managers can once more evaluate how well the employee has done in integrating into the culture. In essence, managers must really see this as part of their jobs, part of “managing” to get the greatest effectiveness out of their employees, rather than as a burden passed down from the onboarding team.

Best Principle #8: Brand your onboarding program—and brand it appropriately.

Outfitting the onboarding program with a unique brand sets the tone and distinguishes the corporate culture from an external brand identity. According to one executive we spoke with, branding new-hire programs does not only “improve the new employee’s perception of the company, but it provides continuity from the heavily-branded recruiting process.” Starwood, one of the world’s largest hotel and leisure companies, offers its branded StarwoodONE intranet for use as a common ground for new hires. This portal connects employees across the firm’s different brands, serving as a reference resource for all things Starwood. Starbucks pursues internal branding on the first day of a new hire’s tenure by offering what is known as the “Starbucks Experience.” The firm spends the first hour of this day in coffee education, allowing the new hire to taste a half-dozen or so different roasts, much as a sommelier would taste wine. Leveraging its unique brand, Starbucks ensures that a new hire feels he or she works for a unique and world-class employer with a clear and cohesive culture.

Sometimes a firm seeks to achieve absolute congruence between the organizational culture and a firm’s external consumer brand. In this case, the company should be sure to permeate all onboarding materials with a look, feel, and messaging consistent with the brand. Apple provides a great example here. Masterful at conveying its brand values of simplicity and high-end experience to consumers, Apple also applies the same conceptual and design vocabulary to the welcome and employee orientation packets it offers new hires. Enthused with the trademark simplicity and intuitive nature of these materials, one new hire reported: “... any company that can give this much attention to detail just in their HR paperwork should be fun to work for. I am looking forward to this new adventure.”6 In Apple’s case, the onboarding experience reflects the culture that the firm wants to maintain. It sets the standard for what management wants new hires to adopt on Day One.

Best Principle #9: Get everyone involved.

Other onboarding advisors recommend that employees receive the names and start date of new hires so they can extend a warm welcome. This is great, but it would help far more to alert surrounding veteran employees to the identity of the new hire’s mentor. That way, veteran employees can alert the mentor when, say, Allison makes a cultural misstep or, alternatively, is fitting especially well into the new culture. Perhaps the most important thing a company can do is involve senior leaders. Robert W. Baird & Co. holds a Professional Development Forum at which senior leaders moderate panel discussions and the CEO leads a question-and-answer session for new hires. In breakout sessions, new hires learn about communications skills and project management, topics that bear significantly on any company’s performance values.7 As we covered earlier, Baird also involves mentors, coaches, corporate HR, and the branch manager in each new hire’s onboarding process. At Bank of America, the company goes so far as to involve direct reports in the onboarding process of their executive hires. Through a facilitated exercise by an onboarding coach, the executive’s direct reports are polled and involved in providing feedback to the executive on his or her performance thus far with the team. They also share cultural norms and performance values that will be important for them all to work together effectively as a team.

A letter every quarter from the CEO would help reinforce messages about the company culture, as would the sort of presentation that Netflix’s CEO created. If best-in-class onboarding is inherently systemic, it falls on the CEO to set the broader agenda for teaching the nuance of culture for new hires, acknowledge the adaptation required of new hires, and offer the organization’s guidance. Division heads and functional leaders should be engaged in talking with new hires about their businesses and the cultures of their organizations. The new hire’s manager also plays a critical role in this process, holding conversations regarding culture at performance review time and when starting a new assignment. Getting everyone involved requires that you make a compelling case that this issue is important, something that your diagnostic (see Chapter 8) can help surface properly.

Best Principle #10: Take it into the field.

Building on Best Principle #5, we emphasize that in-the-field experiences can provide a great opportunity for cultural learning; after all, acculturation naturally occurs here, even without the aid of formal onboarding. Starbucks encourages its corporate employees to work a retail counter shift on a volunteer basis during the holidays, ensuring that all new hires are in the field within their first year and learning the “Starbucks experience.” The program is popular, inspiring near universal participation. As a Starbucks’ VP told us, “this kind of flow of communication among different segments is just what staying [culturally] small is about.” The program’s volunteer nature, and the fact that it is so well attended, itself conveys the company’s performance value of being motivated to understand customers and the customer experience. Perhaps one of the most extensive in-the-field programs we know of is at an industrial manufacturing company that makes diverse products for various markets. The company invests in a 270-day immersion program for their senior hires. Throughout that period, and before taking on their actual duties, managers spend their time going from business unit to business unit, function to function, and meeting to meeting, soaking in literally dozens of businesses and the cultures that support them. By the time they take on their roles, new hires can operate at peak effectiveness relative to the organization’s needs, since they possess deep knowledge of “company-think” an understanding of performance values, and strong social networks. This is an outstanding investment on the company’s part. Even if your company can’t afford the same commitment, the company’s approach suggests what state of the art looks like, offering general principles that can inspire your own, less intensive program design.

Summing Up

Cultural acclimation is a vital component of a best-in-class onboarding program. To improve retention, productivity, and related goals, and to enlist new hires in cultural transformation, firms should pursue open, honest, authentic conversations about organizational culture with new hires. The point isn’t to assure total conformity, but rather to raise awareness of cultural realities so that new hires can better navigate them. Program designers first need to take stock of their organizational culture via a cultural audit. With a sense of the culture in hand, managers should then frame and deliver messages that truthfully convey over time the subtleties and nuances of the culture. Overall, orienting new hires properly isn’t a quick and dirty task; it requires thoughtful program design and the involvement of stakeholders across the organization. It’s worth the effort, though. As top firms know, taking the time to talk about culture results in happier, better-adjusted employees who work effectively for the ends intended. Simply put, it surfaces and releases hidden value.

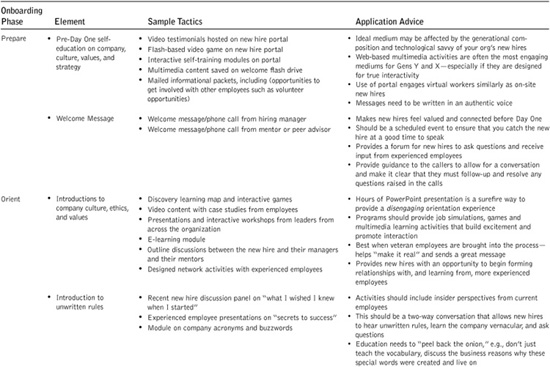

Table 3.3 Cultural Mastery Onboarding Elements—Sample Tactics