6

“LIMITED UPSIDE

IN FLYING BLIND”:

DRIVING STRATEGIC

INSIGHT AND IMPACT

During college, one of the authors of this book, Mark Stein, was fortunate enough to land a summer internship in the corporate headquarters of premium ice cream company, Häagen-Dazs. At the time, with an accounting degree in hand, Mark was planning on a career in finance, and this internship working with numbers seemed like a great opportunity—not least because every day four tubs of ice cream were delivered fresh from the factory line to the corporate headquarters’ office kitchen. Water cooler breaks are far more satisfying with ice cream! Most certainly, it was not a bad gig for a college kid in the summer.

After a few weeks on the job, though, Mark’s enthusiasm waned. His main assignment was to measure and build by 2 PM each day a 28-page report on the corporation’s fulfillment of customer orders. This report conveyed the daily performance and weekly, monthly, and annual trends around product count shortages, flavor shortages, and damaged product count. It contained graphs showing the highest and lowest performing days broken down by distribution center, customer, ice cream flavor, and SKU. The strange thing was that the daily range of performance—for all of these factors—never dipped below 98.20 or rose above 99.40.

Given the narrow deviation, Mark did not understand the point of this exercise. It seemed like he was just spinning his wheels, and as a result, he felt bored and unhappy (except for the incoming fresh ice cream). He grew terribly disillusioned with the prospect of graduation and work at big companies. He even found himself rethinking his career choice altogether.

Everything changed one afternoon when Mark was delivering the report to an executive who stopped and asked how the internship was going. With little to lose, Mark expressed gratitude for the job but frustration with the focus of his work and the report he was preparing. The executive, Steve, quickly got the point and invited Mark to sit down for a talk. As Steve explained, the Häagen-Dazs brand was defined by quality in every regard and at levels unheard of in ice cream category. This quality focus enabled the company to charge a premium price to its customers (largely grocery chains) and get the shelf space it needed to drive growth. To execute on its strategy, the company needed to ensure a top-quality product and top-quality experience—for both the customers (e.g., the grocery store retailing companies) and the consumers who ultimately enjoyed the product. In addition to the best flavors and highest quality ingredients and recipe, Häagen-Dazs had to ensure that every part of the supply chain cooperated in delivering excellence. The company had to deliver the right flavors, in the right quantities, to the right markets, and at the right times. It was unacceptable to send product that had been damaged or that had dropped even a few degrees and refroze in transit from factory to distribution center and distribution center to grocer’s freezer.

That was not all. As Steve related, the company had to convince retailers to support its premium brand positioning in its merchandising, care of the product, and final provision of the product (adding a freezer bag to every consumer’s shopping bag). In addition, the company preferred its stores to avoid discounting the product’s selling price so as to help maintain its premium brand. The brand, in essence, comprised a core operating requirement and central tenant for the company’s strategy to grow market share, maximize profit margin, and provide investors with a high return on investment. Steve went on to relate actions he had taken in the course of the summer when noticing tiny inflection points in Mark’s reports, and he also reported how people had lost their jobs over the years for neglecting seemingly minor production imperatives. The bottom line: Operational excellence mattered. Analysis of the numbers Mark provided helped managers take steps to maintain high quality and grow shareholder value.

With this understanding in place, Mark’s job took on a whole new meaning. When he saw patterns in the numbers, he got excited because he could connect them with something fundamental. Within a few days, Mark became part of the conversation on improving performance. Going back to perform an analysis that nobody else had considered doing, he noticed that one particular retailer had received more bad product than others over the course of the past 6 months. Now things were getting exciting. Mark brought this to the attention of the account manager and the operations lead. Together the managers determined an action plan to ensure that this customer, who didn’t deserve sub-par treatment, would not be subject to it any longer. What had started as a disappointing experience eventually led to Mark developing a special interest in his managerial accounting classes the following fall (classes that focused not on financial accounting and more on using accounting to identify improvement opportunities). As he had learned, accounting was not just about adding up numbers; it had a real impact on business decisions, management, and company performance. A single conversation about strategy, done right, transformed his internship and helped determine his ultimate career path. Even without consideration of the free ice cream, Häagen-Dazs had offered the perfect internship experience.

Companies today spend a lot of time and money making sure they get their strategies right. Yet they usually fall short in communicating that strategy to new hires and existing employees alike. According to the tests we’ve conducted, if you ask five of your peers to articulate what your company’s, business unit, or functional strategy is, you are likely to get five answers that barely resemble one another. People are fuzzy not only about what the firm’s future direction is, but the reasons behind what the current operations are designed to accomplish. What are we really doing right now? What exactly is our business model? How do we think differently than our competitors, and why? What are we doing to win in the marketplace? Why will it work and what will it do for us? And what impact should these answers have on how I perform in my specific role?

Most firms today do not integrate strategy education into orientation for any rank of employee, lower level or executives. New hires usually get, at most, a cursory presentation of the company’s “mission and vision.” The presentation tends to contain short statements that amount to watered down “good citizenship” statements—proclamations of how committed the company is to providing opportunity to employees, caring for the environment, delivering profit for shareholders, and “being the best we can be.” If a company does provide some level of indoctrination into strategy, it is usually delivered informally and through one-on-one conversations with peers, and mostly this is reserved for executives.

As we argue in this chapter, all new hires should get at least some substantive education about strategy as applied to the company, business unit, function, and role, with links forged between these piece parts. Like executive hires, new front-line employees can perform at much higher levels when they understand how their day-to-day work contributes to the firm’s overall success, and when they are bought into the actual “action plan.” By immersing all new hires into organizational strategies, you can motivate and inspire your evolving workforce, in the process driving key operating metrics such as engagement, job satisfaction, loyalty, productivity, growth, and profit. You can also go further and drive organizational transformation in support of key strategic initiatives.

This last point is an important one. Managers seeking to drive enterprise transformation should help workers understand how their specific actions connect to the strategy. Our greatest aspiration is that this discussion will serve as something of a wake-up call: Driving change is not just about attention-getting measures, like a big investment in new technology or merging with another company. It can and should be about mobilizing the workforce to approach their daily work differently, with new goals in mind. By taking relatively simple steps to communicate strategy better to a key audience—new hires—you can enroll these agents of change and put your firm on the path to real, profound transformation.

Defining Strategy

Although many employees do not understand a firm’s strategy, the words “strategy” and “strategic” do get thrown around a lot, to the point where their meaning becomes unclear. What is strategy exactly? What specific topics should companies strive to communicate to new hires when talking about strategy? We like the definition of strategy offered by Gerry Johnson, Kevan Scholes, and Richard Whittington in their textbook Exploring Corporate Strategy: “Strategy is the direction and scope of an organization over the long term, which achieves advantage in a changing environment through its configuration of resources and competencies with the aim of fulfilling stakeholder expectations.”1 Working with this definition a bit, we believe that firms should communicate two basic points about their strategy to new hires as part of onboarding: The firm’s “win plan” for succeeding in its markets, and the “operating conditions.” This win plan should include information about the intended direction and scope of the organization as well as the advantages these yield relative to stakeholder expectations. The “operating conditions” that feed into the strategy refers specifically to information about the firm’s markets and competitors (the environment) and its suppliers (resources and competencies). For each of these two broad areas (“win plan” and “operating conditions”), the point is to convey necessary information rather than engage new hires in an extended process of analyzing, critiquing, or forming the firm’s strategy. This information needs to be conveyed as it applies at the corporate, business unit, functional and task levels (a configuration mirroring Mark’s daily Häagen-Dazs delivery report).

Talking about the “win plan” means alerting new hires to the organization’s targets or desired outcomes—goals such as increasing market share, profit margin, and the like. It also means talking about how the organization hopes to achieve these goals. A medical device company might discuss as its win plan getting more customer share by increasing the size of the sales force so that the firm can spend twice as much time with doctors as the leading competitor. An alternate win plan might involve spending twice as much as the leading competitor on R&D to develop a technically advanced product. Another win plan might focus on outspending the competition on clinical trials to create superior proof points on product performance. Still another win plan might involve outspending in a direct-to-consumer marketing campaign designed to create end-patient demand for the product segment and product brand. These are four different strategies for increasing revenue and ultimately share. If you came onboard as a new hire who followed the first strategy, and your old firm had been following the second, then you’d probably find the tactics of your new employer confusing and even misguided unless someone at your new employer explained the tactics and underlying strategy to you. And if you were a young hire without industry experience, you would not understand what you were doing at all (like Mark initially at Häagen-Dazs).

Organizations need to give new hires sufficient context for understanding the win plan by offering insight into the operating conditions that inform this strategy and its execution. Sharing information about competitors, company resources, and decisions associated with allocating those resources is especially important. Many new hires who have not worked in an industry before do not know much about the other players serving a market, including the extent of the competition, how individual competitors behave, and the strengths and weaknesses of each.

One useful approach might be for an onboarding program to break the competition down according to a widely used and fundamental framework in the strategy world—management consultant Michael Porter’s Five Forces framework for industry analysis. New hires could learn about the threat of substitute offerings competing with the firm’s own; the threat of new players entering the firm’s market; how intense the rivalry among competitors is in the industry; information about customer buying power; and information about the bargaining power of suppliers. Since all of these affect the formulation and success of an organization’s win plan, communicating them to new hires goes a long way toward rendering the firm’s win plan comprehensible in their eyes. Front-line employees especially need this orientation, as they are typically operating along a single thread of the overall strategy and have very little opportunity to otherwise gain a greater perspective.

Let’s consider an example of how a company might communicate competitive information. For years, Home Depot had enjoyed a largely uncompetitive landscape, exploiting its scale advantages over smaller local retailers and providing its customers with discount prices and a broad selection of common products. Front-line employees were well conditioned to Home Depot’s retail platform and long-term strategy (whether or not if it was ever explicitly taught to them).

Home Depot added a new element to its strategy about 5 years ago when, in response to competition from Lowe’s, it decided to differentiate itself by offering customers unique products they could not find anywhere else. Home Depot created an in-house product development function and an entirely new sourcing strategy, investing in company brands and technologies. To execute this strategy, Home Depot needed to bring its sourcing and marketing organizations on board. Yet it also would be well served if all front-line retail new hires in Home Depot’s stores understood the new strategy and its significance. Without such perspective, front-line retail hires would never understand the importance, for example, of highlighting the tools and other products that are only available at Home Depot—and specifically what about them makes them special. New hires might have performed such tasks if management specifically directed them to do so, but they would not have done it with anywhere the same zeal unless managers had explained Home Depot’s new strategy to improve margins and maintain share against a growing formidable competitor.

Companies should also take care to provide new hires with sufficient information about suppliers. Questions you might answer include:

• Are suppliers exclusive to us, or do they serve all industry players with the same products? Regardless of this answer, employees should understand the implications of the current supply structure.

• What are we asking of our key suppliers? Is it innovation? Low cost? Flexibility?

• Where have we chosen to vertically integrate? Have competitors decided similarly? What are the implications?

• How healthy are our relationships with key suppliers? What are the points of tension?

If an organization could articulate that its win plan relies heavily on having differentiated, innovative products, and that the strategic sourcing (supply) organization should therefore negotiate exclusive deals with suppliers who can provide unique goods with proper incentives, then the firm could execute well against its strategy of being an industry innovator. Behavior on the ground in the sourcing department would change; new hires might try to nurture long-term relationships with suppliers rather than aim at lowest cost no matter what. Customers comprise another especially important component of the strategic landscape. There are many questions to answer here, as part of onboarding. What customer segments exist and which has the firm chosen to target? What does the differentiated strategy look like by segment? What is our relative competitive position within each segment and why? What other choices do customers have when making a purchasing decision? What prospect is there for an industry-transformative substitute emerging for the products our organization sells?

As part of a customer analysis, firms should also clue new hires into key demand drivers. If you operate in an environment with a channel, you will need to explain this at multiple levels; what a new hire may think of as a customer may actually be a channel. What drives behavior at the channel level and with whom is the firm competing? New hires should also understand the organization’s brands—what do the brands represent? More fundamentally, what value proposition does the brand communicate in customers’ minds, and how does it compare with competitors’ brands? How should the new hire’s role reflect this brand definition?

Another topic area new hires should know about involves the resources at the firm’s disposal to meet its objectives. What are the key resources? What choices have we made to allocate our resources? Is our infrastructure stable or does it require constant innovation and investment? Do we own our supply chain or outsource it? Why? What technical competencies (trademarks, knowledge) can we bring to bear? Without this information, new hires will prove less equipped to think through issues and come up with appropriate approaches. More concerning, they will likely distrust the firm’s actions, when in reality these new hires simply do not have sufficient perspective to pass judgment. If your goal is to energize and excite new hires to support company strategy, the last thing you want is a hire unnecessarily skeptical from the get-go.

As you can see, a full and useful strategic discussion (and this is hardly an exhaustive list) is potentially quite extensive—a good reason why strategic education should occur progressively throughout the first year rather than all at once during Week One orientation. In addition to the breadth of the topics, we have plenty of evidence, as earlier discussed, that new hires do not have sufficient context to absorb everything in the first week. You can present strategy during that week, preferably in the form of a two-way dialogue, but at the very least you need to repeat and extend the education throughout the first year as new hires develop the proper experiential context to absorb it. By continuing the discussion throughout the first year and involving company leadership, you get the double impact of not only teaching but also reiterating the company’s commitment to the strategy. This can have an enormous effect, raising new hires’ confidence and exciting their work ethics, given that they obviously have come to work for a competent and directed team. Given how poorly most companies engage employees around their strategic win plans, you have a very good chance of standing out in stark and welcome contrast to your new hires’ last employer.

With understanding and development of a common view as the ultimate goals, strategic education needs to focus not only on short-term strategies, but also the longer-term vision. Companies should take care to reveal in depth what the organization aspires to in the broadest sense and how the company’s business plan will help them get there. The onboarding system needs to make clear to new hires what the firm is doing right now to pursue the strategy, including where the firm is making investments; where the weak points are; what the firm is doing to address them; and what kind of pressures the firm is under, both short and long term, to realize its strategies. With this perspective in hand, your new hires will be more inspired, have a greater understanding of your company’s actions and inactions, and become more confident in their choice of employer and more excited about their future. Most importantly for your stakeholders, the new hires will become far more effective in helping the enterprise deliver against its intended strategy.

Aha Moments and Motivation

It is difficult to present hard data about strategy education’s impact on the organization’s goals, since too few firms have invested materially in orienting employees (much less new hires) to the strategy in any substantive or formal way beyond the senior ranks. However, we know from our experience working with winning and struggling companies alike on business improvement initiatives that strategy conversations radically improve the chance that the group will have an “Aha moment” and either form the critical operational insight or come to support an insight that a group member has already advanced. Both outcomes offer huge advantages.

Strategy implies action to achieve the objective set forth by the plan. To the extent an organization requires its workforce to think and act on behalf of the enterprise, understanding the strategy and the underlying strategic landscape will make all of the difference between achieving random and intended outcomes. Empowering the organization to understand the strategy creates leverage for the organization and radically reduces wasted energy that is applied in conflict with the plan. Moreover, the very process of socializing the organization’s understanding of its strategic landscape and its associated strategy with new hires helps fine-tune the strategy as opinions and insights come to the table in the course of discussion.

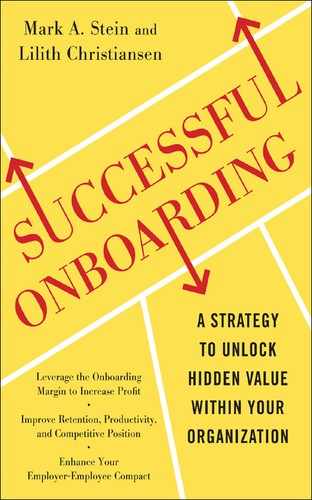

As Figure 6.1 conveys, strategic orientation and immersion helps yield the Onboarding Margin by carving out value in three distinct ways.

Figure 6.1 From Immersion to Impact

The more versed employees become in the strategy, the more they begin to regard their everyday work through that lens. They begin to notice elements of their jobs they didn’t before and tie these elements to the strategy. They also start to ponder their experiences and observations on the job, leading to “Aha!” moments when they realize parts of the business process that are inconsistent with strategy and discover improvements that can push the strategy forward. These eureka moments in turn have the derivative effect of improving how the organization does business—whether by serving customers better, meeting additional customer needs, or developing more efficient work processes.

A great deal of data exists to support the idea that any employee can potentially help improve an enterprise. Toyota has a system in place that queries front-line employees for ideas on how to execute the company’s strategy. The result: More than a million ideas a year2—and despite recent product safety issues, a company renowned for continuously improving and innovating its product design, features, and operational effectiveness. Google News originated from a little tool that one of the company’s developers devised in the wake of 9/11 to help himself find news about the event.3 Now while this single employee at Google may have had a personal need for his news service, it ultimately required an understanding of Google’s strategy for this personal project to become a major competitive force, one that many argue is largely responsible for challenging and reshaping the news and periodical publication industries.

Google’s leadership simplified its strategy and widely communicated it with a single sentence that it refers to as its mission: “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” We cannot tell you if Google News’ originating employee in question understood this strategy, but it was put out there loud and clear. If Google’s strategy hadn’t been circulating in some form, the chances that this innovation would have made it to the marketplace and in such a strategically consistent form would have plummeted. It would have required dumb luck—not something leaders can afford to rely on.

Beyond leading to “aha moments,” we’ve seen strong anecdotal evidence suggesting that the sharing of strategic information has increased motivation and led to positive results. During the economic downturn of 2008, when many firms were laying off employees and many companies saw employee engagement at an all-time low, one new mid-level employee at a mid-sized company we know of remained engaged and happy with his job (and of course there were likely others). This individual had been given information about the strategic context by his mentor, so he understood why he had been spared from layoffs and what the company was doing to weather the storm. Further, he understood how his daily work helped the company execute its recession-era strategy. Because this employee was committed enough to the firm and really wanted to help it succeed, he took it upon himself to share this strategy with his peers and more junior employees, helping get them engaged around the long-term opportunities at the company despite the current disruptions. From our work with this company, we learned that his behind the scenes conversations helped sway a number of unhappy employees to stay, helping this company continue to deliver on promises during this stressful period and remain healthier than the competition.

Conversely, we have also seen situations in which firms have discouraged the sharing of strategic information and seen the morale of individual new hires suffer as a result. One new hire, an experienced executive assistant, had become adept at serving as the “gatekeeper” for the busy executives whom she served in her past employment, largely because of her knowledge of company strategy collected in the course of her 15 years at the company. Understanding the roles individual executives served relative to the company’s goals, she understood who needed to be seen right away, who or what issues could wait, and how to support prioritization for the executives’ agendas. At her new company, her “onboarding” consisted of showing her where the kitchen was, how the executives liked their coffee, how to answer the phones, and when to feed the fish.

Eager to succeed, this employee introduced herself to others in the office and made a point of learning about strategy on her own. At one point, she emailed the management team and asked to speak with them for 10 minutes to get a better understanding of their individual roles and how they all fit into the big picture. Upon receiving this email invitation, her hiring manager called her to tell her this was not a good use of her time. She reminded her that she supported the CEO and CFO, not the other functional leaders, and that she should not stray beyond her standard job duties. Not surprisingly, this superb executive assistant chose to leave her new job within one month. Her hiring manager had not only failed to deliver an onboarding experience worthy of their needs; this manager’s lack of appreciation of strategic education caused her to actually resist when an entrepreneurial new hire brought the need for it to her attention.

Some of our clients have found strategic orientation a valuable means to prevent anticipated declines in motivation. One of our clients, a technology company, traditionally gave most employees an assigned workspace in the corporate office. Over the last several years, as their business model changed, they found that more of their staff were spending a greater majority of their time working on-site at customer locations and other transient locations outside the office. This transition, coupled with growth demands, was putting pressure on the company’s real estate needs. There was no more space to grow at their current location, yet the average staff member only used their offices one-third of the time.

Our client decided to merge a business strategy—providing better service to its customers by working more closely with them at their locations—with an operational strategy of transitioning the headquarters workspaces into “hotel-ing” sites. Employees wouldn’t occupy permanent workstations; rather they’d have a “locker” of sorts for storage when in the office as well as a workstation reserved for the duration of their stay. As you can imagine, this change might have aroused dissatisfaction among employees, who generally enjoyed being able to come back home to personalized workspaces. However, with careful articulation of the strategy, the company was able to win over employees and prevent major disillusionment around this strategic move. Employees saw that the move made sense, for it would enable the company to serve its clients better and grow without much additional capital investment.

New Blood

Another important way strategic orientation benefits a company is by operating as a driving force in support of either a newly determined “business transformation” (initiatives in which entirely new business strategies and/or outcomes are pursued) or “organizational transformation” (initiatives to change how a company thinks or behaves). Farmers Insurance, for instance, wanted to focus the attention of field employees on customers. To affect that strategic change, the company revised its training program to include not just experience with live customer interactions, but also immersion in the kind of industry knowledge vital to understanding and executing a company’s strategy.4

Oddly, when seeking to realize a transformation, most managers have severely underutilized their employee base to drive change. Companies generally seek to avoid tackling organizational transformation; when they do attempt it, they take a top-down, command and control approach with limited results. A common approach is to acquire another company or change leaders—options that deliver very moderate results. Given our earlier reference to the Attrition Law of Thirds (because of attrition, you will turn over a full third of your work force every three years), we hope you can see how onboarding represents an amazing opportunity to enlist new hires into a transformative strategy.

If your company is anything like most, this line of thinking probably diverges starkly from how you generally view new hires. Often hiring managers responsible for a strategic shift view new entrants as something of a necessary evil. They only accept the idea of relying on new hires once they discover that veteran employees are too busy with existing assignments and the requirements of running the current business to participate in change-related activities.

Let’s make this notion of onboarding as a pathway to change more concrete. Consider a US-based cable television company. Thirty years ago, players in this market operated as legal and licensed local monopolies; the cost of digging up streets and laying cable was so great that no company would do it without an exclusive contract with the local municipality. Once a cable company obtained this contract, no great impetus existed for it to provide superior customer service or innovate the product. As local cable operators started to merge with one another and achieve greater scale, they gained negotiating leverage over suppliers (content providers) and spread the other operating costs across more households.

By the 1990s, new forms of competition—satellite television, DVDs, the Internet, gaming consoles, fiberoptic competition from Verizon and AT&T, direct to consumer distribution models such as Apple’s iTunes, among many others—slowly but surely chipped away at the exclusive domain that cable companies enjoyed for so long. This new reality has forced cable operators to become much more concerned with customer service. But how do you improve customer service dramatically? How do you transform an organization that had provided very low levels of satisfying customer care into one that takes as its daily mission providing superior service to customers? This is where onboarding can play a huge role.

Companies that have been doing business a certain way for a long time tend to have employees conditioned to do things the old way. By contrast, organizations interested in change can hire new employees primed and ready to behave in a new way. What this “new blood” requires is information about the transformation and how their role fits in. They also need the strong support of leadership that sees this incoming class for what they are: Brand-new and expensive capital investments with great potential. New hires need to understand that they are change agents; otherwise, they will not know how to relate to veteran workers they’ll encounter on the job. If you can provide these things, you’ll find that new hires can push transformation farther on account of their open-mindedness and willingness to listen, their motivation to perform and prove themselves (they just got the job after all), and the knowledge about best practices, trends, and technology they bring from prior experiences.

Strategic knowledge empowers new hires to make proactive choices in support of the new strategy. It is easy to see the importance of indoctrinating a newly hired executive into the strategy of a transforming company—typically, strategy becomes central to the discussion and evaluation during the recruiting process. What is less obvious to management is the benefit that comes from indoctrinating an average new hire. Strategy orientation allows the typical employee to be more connected to the strategy and therefore further it through his or her everyday activities. No longer is the job transactional; with understanding of the strategy under his or her belt, a new hire is on a mission.

If your company’s strategy is to be your industry’s lowest cost provider, then it might make great sense to reduce working capital needs, minimize interest expense from all bank lines of credit, eliminate any cost that is not necessary and minimize all others, and go to market with the lowest possible price. If your organization can explain this strategy and the importance of a given tactic—e.g., lowering interest expense by reducing your line of credit to your new employees in the collections department—then new hires might help push the strategy forward by leaning on customers to pay their bills quickly.

Alternatively, if your company is pursuing a strategy of premium service and premium pricing, then you can imagine how important it might be to communicate that strategy to your collections department. Although collections remain critically important, greater customer accommodation on payment terms is likely far more appropriate than it would have been in the first scenario. Not providing this context will very likely impede the company’s chance to deliver on its strategic plan—and this is true even when new hires perform functions that at first glance do not seem most relevant to the strategy.

In speaking of strategy immersion’s impact on change, or indeed, in speaking to any of the benefits that such initiation might bring a company, it’s important to acknowledge that some new hires might not care about strategy at first. Perhaps they don’t feel incentivized enough to care, or perhaps nobody has gotten them to care about strategy in the past. It is the job of onboarding (the collective whole of the onboarding stakeholders) to give them the motivation and incentive they need to care. If you talk about strategy with the employees, some will get it and will be moved by it. Guess what? You just activated drive and ambition. You have also just given new hires—even those with low-level, hourly wage jobs—reason to believe that their employer is a company at which they can build a career (or if nothing else, keep their job, as this employer may actually have a business plan that will result in job growth). If only a small number of new hires—say, 5%—get the strategy and run with it, you will see a big payoff in terms of “aha” moments, higher productivity, and an organization more aligned with its strategy of transformation. You will realize a bump in your Onboarding Margin, and you should be proud of its impact.

Making New Hires Strategic

Now that we’ve established how powerful strategy immersion can be, let’s consider how a company should incorporate this orientation as part of a state-of-the-art, strategic onboarding program. In other chapters, we’ve provided “best principles” drawn from our experiences working with and researching best-in-class onboarding companies. In this case, since few if any companies have incorporated it as part of onboarding (one more reason why it constitutes a golden opportunity for a firm interested in gaining competitive advantage), what we offer here are our “best principles” for establishing strategy orientation based on our general organizational development and performance improvement experience.

Best Principle #1: Don’t be afraid of sharing the strategy.

It’s important that we address the perceived risks associated with teaching business strategy to your employees. You might think that the more of your strategy you put out in the open, the greater the chances your competition will learn of it. We believe that the benefits far outweigh the risks. You already have employees, contractors, suppliers, and customers who talk to your competition, not to mention ex-employees. Your company already likely posts company performance against key performance indicators (KPIs). Also, analysts may already cover your company. And, we can assure you that if you have a distinct strategy your competition has already figured it out from the actions that your company has taken. Knowing your strategy is quite different than being able to execute it or being able to guard against it. And you likely have legal protection on your side in the form of non-disclosure agreements with your new employees. The bottom line is that the risks associated with letting new hires into the tent are far smaller than the risks of keeping them away from it. You can always limit how much depth you share, and you can also parse information on a need-to-know basis (albeit with a potentially limiting impact on the Onboarding Margin). Overall, we encourage you to share and realize the benefits that come when your new workforce contributes as much as possible to realizing your strategy.

Best Principle #2: Provide rich examples of how other employees have delivered on your strategy.

Providing illustrative examples is one of the best ways to teach concepts to new hires, and this is certainly the case with strategy. We advise showing new hires the impact that individuals have had in furthering the strategy through their own work. Ideally you should show two kinds of examples: (1) the standard fare that shows how work activities are aligned against the strategy; and (2) examples of employees making independent decisions in the course of their work because of, and in concert with, the strategy. Examples can come from any area of the business, and the more you gather, the better. Ideally, you can select and craft these stories so that every new hire has a chance to see themselves in the stories. At a minimum, take care to provide stories that cover the largest groups of employees: Front-line, customer-facing employees; back office/administrative; production; management, etc. With the second type of examples, you should demonstrate how the individual worker’s actions went beyond their ordinary roles and responsibilities, how this worker included others in their initiative (including gaining buy-in), and how this worker’s actions made a real difference for the company and its strategy. Stories about “aha” moments might prove most interesting and make the biggest impression, yet examples depicting everyday activities will pay off, too.

Here is an example of the kind of story you might share: At a mid-sized company, the leadership team regularly engaged employees in strategy discussion regarding the key areas of focus for the firm. At one of these meetings in early 2008, the president shared key strategies the company would pursue for revenue growth as well as some of the activities that were being taken to reduce costs in non-strategic spend categories (i.e., the company was happy to cut costs in areas that were not going to drive revenue growth). Not long after this meeting, one new employee had an idea to help with the cost-cutting strategy. His roommate was a computer programmer and worked for a firm that provided outsourced IT support. In swapping stories about their respective days at work, the employee realized that outsourcing IT might well work for his own company, lowering costs and providing better service. The firm had grown so large that its IT staff could not serve everyone’s needs; when something went wrong, it always took too long to fix. The new hire recommended his idea to the leadership. After some additional investigation, the company determined that it should indeed outsource IT, resulting in material cost savings as well as service improvements. To make your stories successful, all you need to include is the strategy set-up, idea, actions, and outcome.

Learning about stories like this, individual employees will imagine themselves in the position of the entry-level employee. They will understand in concrete terms how they can make a difference. They will be more motivated to share creative thinking so as to help push the strategy further.

Best Principle #3: Incorporate periodic formal strategic insight interviews.

Your system should implement a formal process to capture your new hires’ insights around strategy. This process might begin during Week One with an initial welcome interview similar to one we advocate around culture. Formal follow up discussions should be scheduled and can take place at the 6-, 9-, and 12-month points. At all of these meetings, the conversation should run in both directions, with the new hire’s manager or mentor first gauging the employee’s understanding of the strategy and then asking the new hire to share his or her ideas. These ideas should include suggestions to inform any revisions to the strategy, but with greater focus on business unit, function, and role-specific related issues, and they should also include ideas for how to better execute the current strategy.

By engaging new hires in this way, the conversation reinforces a key principle of the new employer-employee compact: That the company truly cares about the new hire’s opinions and ideas and is willing to invest in the time to hear them. Reinforcing that the company cares is important not merely because it helps the new hire to feel good. “Truly cares” means that your company is going through this exercise because it expects a contribution of significance from the new hire community on this front. The “expects” part is important; there is no need to put undue pressure on your new hire class, but you should set an expectation early (ideally in the recruiting stage) that the company believes all employees can potentially to contribute to its plans. You should communicate this upon the new hire’s arrival, throughout the various orientation communications, as part of the broader onboarding conversation, and most certainly in the core periodic check points. Employees will come away more motivated than ever to do their best because they feel that they are being listened to and that the potential exists for them to make a real difference.

Solicitation of strategic insights can also take place in the form of an open-ended survey as opposed to an actual interview. For larger enterprises, insight collection/synthesis is obviously easier with electronic collection, and as long as you have a very strong analyst reviewing the submissions, it can be an efficient and effective exercise. We strongly suggest that you collect strategic insights live in the form of discussion with a mentor or managers; that way, you can in the same forum provide feedback and together make plans with the new hire to socialize or take action on the ideas. Here are some questions we recommend covering:

1. Do you believe you have a good understanding of our company strategy? Business Unit (BU)? Functional? How would you explain it?

2. From your perspective, how are we (the organization) succeeding at executing against these strategies?

3. Do you have any ideas that may help us in executing the strategy?

4. Have you encountered any challenges or hurdles in trying to perform your role in the organization?

5. Have you had any exceptional “successes”—when everything came together and you could see our strategy in action in the work you and/or your colleagues were performing?

After the conversation, the manager or mentor should determine with the new hire what appropriate actions the company could take as a result of the new hire’s ideas. The hiring manager or mentor should also take notes during the conversation so that during a subsequent pulse check or formal interview, the discussion can resume and the manager/mentor can learn if the new hire’s experiences or perceptions have changed.

Ideally you will initiate these exchanges as a distinct discussion, separate from other activities. If this topic becomes a single line item as part of a periodic performance review, than the scope of the strategic discussion will likely be minimized, since other topics at the meeting will likely receive greater airtime.

Best Principle #4: Make use of stakeholder maps.

In our chapter on social networking, we advised that managers help develop stakeholder maps for new hires, identifying specific individuals whom the new hire should approach for specific needs or with specific ideas. Another way to talk about strategy to the new hire is to pull out a stakeholder map and explain how each of these stakeholders will work in concert with the new hire to achieve strategic goals. Using the stakeholder map, and an accompanying organizational chart, helps make the different layers of strategy (corporate, business unit, etc.) visual for new hires; you can literally connect the dots for the new hires as to who is doing what in the organization and why. At the same time, you will also be supporting another part of onboarding, the forging of social connections.

Best Principle #5: Unveil the strategy in layers.

Since strategy is highly detailed, organizations will do best to unveil it progressively and in layers. That way, new hires will not feel overwhelmed with information, and they will have proper context—as noted in Figure 2.7 and accompanying discussion—to make sense of it.

We advise beginning the strategy immersion portion of onboarding with a discussion of the broad, high-level strategy. In the weeks and months ahead, the conversation can then proceed to cover in more detail the new hire’s role and how it supports the overall strategy. It can also explore how the new hire’s function/organization fits in to executing the strategy. When working with the stakeholder map, we advise beginning with organizations that most closely relate to the one to which the new hire belongs and then spiral out from there. Later on in the onboarding year, managers should customize conversations, organizing them in a way that makes sense to the individual new hire’s role and position in the company.

Best Principle #6: Be honest and realistic when talking about strategy.

Do not go overboard trying to inspire your new hires. Do not turn strategy conversations into mere sales pitches. Authenticity inspires, not smoke and mirrors. Think of The Wizard of Oz: In the end, there was no fancy wizard orchestrating events, and the real actions of individuals became inspirational. The CEO and other senior leaders are key here: Honest, heartfelt messages from the firm’s leadership are more than enough to inspire individuals; you simply do not need the hype. If leadership can acknowledge that they have made some trade-offs and tough choices, for better or for worse, new hires will have more confidence in both leadership and the underlying strategy. They will feel motivated to help out because of the collective sacrifices that have already been made. They also will not wind up disillusioned down the road when false expectations raised by the CEO have failed to come to fruition. If leadership prepares new hires for challenges and the road ahead, new hires will feel more inclined to rally. They will be more patient when the company encounters bumps in the road. And they will be more willing to forgive leaders for any mistakes or poor judgments they make.

Best Principle #7: Frame strategic thinking as a skill that employees can develop and that will benefit them in a knowledge economy.

There is a reason strategic thinking stands today as one of the most widely discussed skills and concepts in business literature: Companies rarely succeed if they don’t have a good strategy, and a good strategy will not emerge if companies don’t have employees adept at plotting strategy.

In a knowledge economy, workers’ intellectual skills become more prized assets than the durable goods companies produce. As Peter Drucker noted in his book The Effective Executive, knowledge workers produce with their heads, not their hands, creating ideas, knowledge, and information.5 Organizations are already investing in their human capital by offering more robust training and development programs. Teaching your new hires strategy and strategic thinking as a skill that will enable employees to produce ideas is another way a company can support the new hire’s development.

It is a clear win-win: The organization is preparing its people (or assets) to “produce” more of what is needed by the company to succeed in the future, and the individual gains a valuable skill that makes him or her more marketable when changing companies or simply more successful within the same company. Yet companies need to articulate this to new hires. That way, new hires will possess a stronger sense of participating in and benefiting from a new employer-employee compact.

Best Principle #8: Clue new hires into your strategic priorities.

Not all parts of the strategy are as fixed as others, and not all are prioritized as highly. Part of our firm’s strategy is to have a congenial workplace where young people can learn a lot and work hard. We decided to locate our office in the heart of downtown because we thought new hires would find this neighborhood more attractive. If our lease comes up for renewal and our rent doubles, we might be willing move our offices to an alternative location, even though being downtown is part of our people strategy. We might compromise because a greater strategic priority might be to improve our profits. To understand our company, new hires need to understand how our firm thinks through these issues and how we make decisions that befit our strategy. This nuanced discussion empowers new hires to begin to become a more effective steward and activist of the company’s strategy, as they are equipped to think and act in harmony with the enterprise’s intended path.

Companies need to articulate what their strategic priorities are. That way, they can organize their own efforts to support the firm’s more important strategies when these come into conflict with less important ones. The more new hires understand the priorities, the less they will need to run to superiors to ask for clarification or guidance. And more importantly, the less frustrated they will become, as they will be able to avoid misinterpretation of company actions and intentions. When the strategy is well communicated, organizational efficiency improves, whereas new hires feel more empowered and gain more confidence in their own decision-making abilities.

Summing Up

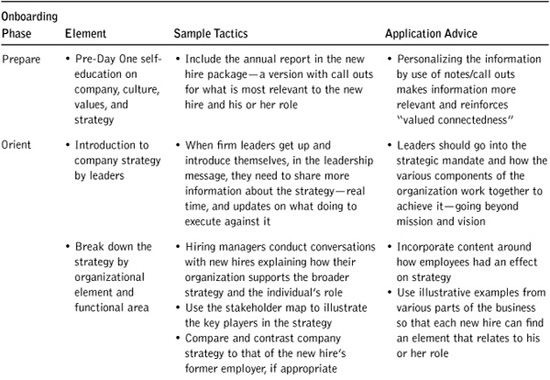

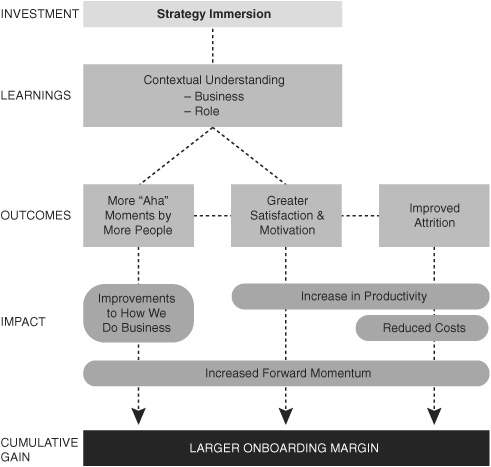

Even more than other onboarding components, strategy immersion for rank-and-file employees remains uncharted territory for most firms. Yet the opportunities are huge. Similar to high-potential executive hires, low-and mid-level employees feel empowered and motivated when they are able to connect what they do every day with the organization’s higher purpose. Engagement increases, and with it productivity and the Onboarding Margin. As an extension of early career support, strategy orientation stands as an important way of redefining the employer-employee compact in a way beneficial for both the company and the new hire. Organizations can realize benefits from strategic onboarding without strategy orientation, yet alerting new hires to the bigger picture remains necessary if companies are to squeeze the most value possible from their onboarding programs. In ways we have suggested, strategy immersion (Table 6.1). works together with social networking, cultural mastery, and early career support; it is the organic meshing of all four that allows for the greatest impact.

So far we have covered the four key topic areas that a strategic onboarding program should include so as to unlock vast new value for organizations. Yet all the thoughtful program content in the world will not do much good if the company fails at execution. Onboarding must be systemic and of extended duration if it is to achieve optimal results, and this means having adequate processes, technologies, and resources in place to coordinate the different players so that the program appears seamless and of superior quality. An onboarding program also needs a system in place for measuring stakeholder performance and holding players accountable for fulfilling their onboarding functions. Like the system of blood vessels assuring that muscles in the human body have the oxygen, nutrients, and other elements they need to perform, administration and governance serve as the life support system for a state-of-the-art onboarding program. They allow enlightened organizations to integrate new hires and prepare them for success, so it is imperative that as a program designer you get them right.

There is a more fundamental point here. The new hire compact that we discuss in this book implies that the entire enterprise cares about the new hire’s future, not just his or her boss. To enact this compact, we have to build into an enterprise’s system a model that ensures that the entire enterprise will attend to the new hire’s success. Organizations have to commit themselves at the deepest levels to retaining the people they bring onboard. They have to put the onus on themselves to identify at-risk people and take steps to remediate problems and turn them around, so as to retain new hires as strong, productive employees.

In the end, the goal becomes to reduce recruiting activities—not because of company stagnation, but because we are more successful with the ones we already brought in. This means putting senior leaders in charge of overseeing the program’s success. It also means that companies should make sure they’ve devoted sufficient administrative and governance resources to onboarding—not just dollars and people, but tools and technology. What those resources are and how a progressive enterprise might deploy them to greatest effect is the subject of the next chapter.

Table 6.1 Interpersonal Network Elements—Sample Tactics