7

THE ONBOARDING MARGIN

LIFE SUPPORT SYSTEM:

ADMINISTRATION AND

GOVERNANCE

You are not alone if your company’s onboarding process is administratively disjointed. On the surface, processing new hire paperwork; outfitting recruits with the necessary supplies, access, tools, and development resources; assigning new hires to a team, a mentor, and a first assignment; among many other requirements, seems basic. It should be easy to manage, right? Unfortunately, it’s not.

At most companies, this process requires tight coordination between stakeholders in almost every function—people who typically lack a formal reporting structure for this activity or accountability to each other. At a minimum, Recruiting, Security, IT, Facilities, Payroll, Legal, Benefits, and the new hire’s manager must play a role in welcoming the new hire. The remainder of the year, a systemic program provides administrative coordination (and direction) for the new hire, hiring manager and system-wide participants, assuring that they can complete training, acclimation, acculturation, skill progression and recognition, progress in role, career development, and performance review activities. To pull it off, you need not only the right technology, people, and resources in place, but a system of governance to measure performance, ensure that all system participants play their role properly, and assess consequences if they fall short.

It is true that flawless onboarding program administration will not by itself materially affect the Onboarding Margin (i.e., productivity or retention). If all that you invest in is cleaning up onboarding administration, you will not likely realize any material return on investment. Even if the administrative process is broken, and no real governance exists, new hires will eventually receive their equipment and gain access to required systems and tools, albeit while experiencing frustrations, annoyances, or unnecessary cost. Further, program administration can be a thankless task; it will only garner attention insomuch as things go wrong. So why bother?

Seamless program administration plays a critical role in ensuring that higher-impact early career progress and support, networking, and development are properly executed. If system participants do not inform and guide new hires toward the key resources available to them and do not play their part more broadly, new hires are far more likely to miss out on learning or developmental opportunities critical to their success at the company. And although program administration alone may not make or break a new hire’s experience, flaws in execution represent one of the most common “gripes” that you hear from new hires. “They weren’t prepared for me,” new hires say. “I didn’t even have a place to sit.” “I had no idea where to go or what was expected from me.” “My manager wasn’t even in the office the whole first week to meet me.” We have all witnessed these initial impressions tarnish a company’s reputation as an employer of choice.

The motive we most commonly hear about for improving program administration is wringing cost and wasted energy out of the process. Automation and centralized oversight can simplify and standardize the onboarding experience and reap significant cost savings for the organization. As senior management realizes the cost benefits, many of our onboarding clients find that improved program administration builds momentum, generating the capital and organizational energy to attack higher-impact program upgrades. Governance, meanwhile, is essentially a higher-level form of administration. It ensures that the firm is doing what the program design says it should do; i.e., address the most critical issues uncovered in the diagnostic. It also involves evaluating on a regular basis (we recommend annually or upon conclusion of a business cycle, whichever is shorter) whether the program design remains the right answer and assessing consequences to participants for failing to perform according to required standards. It is simple: You can have sufficient administrative resources in place, and all the right content, but if you do not have governance, your program will fall short of delivering the value the enterprise deserves with this human capital investment.

This chapter provides general guidelines for governing and administering a strategic onboarding program. It also relates practices we have seen applied to great effect at our clients’ companies and at other leading-edge onboarding organizations. Putting state of the art administration processes behind the programs you choose and executing these programs with excellence clearly means accruing some cost. By now, though, we hope you will consider these costs in their proper perspective, seeing administration and governance as enablers of the great opportunity that onboarding represents. Program administration and its continuous improvement are the foundation for implementing a new employee compact, and as such, a worthy and important investment in your company’s long-term future.

Onboarding’s Administrative Needs

Here is some great news: Your enterprise already possesses the skill set it requires to administer onboarding properly. One thing many successful companies excel at is operational excellence—repetitively doing the same thing over and over again with efficiency and reliability. Large companies are especially adept at simplifying and making routine processes for scale and scope advantage, which is precisely why they often cannot undertake dramatic change all that well (often the skill set of smaller firms). Yet the majority of big companies have not applied this skill to the particular function of bringing onboard its new hires. They’ve refined and systematized processes that relate to production or serving customers, but where onboarding is concerned, the slate remains largely blank.

For processes to become routine and effective, in the sense of delivering consistently great outcomes, you need to:

1. Determine the process objectives.

2. Document the necessary steps for the process.

3. Simplify and optimize the process for cost, service level, and time objectives.

5. Embed a continuous improvement system for the process.

Within the human capital world, we have developed strong administrative processes for things like recruiting, performance assessments, promotions, compensation, benefits administration, labor utilization, and succession planning, among many others. So what does proper administration of onboarding look like?

Let’s start with Week One and the preparation leading up to Week One. Administration means organizing and overseeing the numerous preparation and orientation processes—getting everyone’s security, legal, confidentiality, and compliance forms taken care of efficiently and completely and delivering information to new hires (company policies, benefits, etc.). It also means giving new hires tools they need to do their jobs, including business cards, computers, mobile phones, telephone extensions and voicemail, email addresses, email system distribution groups, security access, and much more. It includes preparing the new hire’s manager about the new hire start date and prepping the department on the new hire’s background, strengths, weaknesses, and objectives. It includes determining the new hire’s first assignments and providing the necessary orientation.

At the childcare provider company Bright Horizons, everything is ready upon the new employee’s arrival, including nameplate, security access, phone system, email, desktop, and paperwork.1 Unfortunately, most companies do a far less comprehensive job prepping for and delivering Week One, and people do talk about it. Many HR task leaders presented with the task of addressing onboarding are told to focus on this world—in our view, a short sighted approach to onboarding. Managers in charge of onboarding notice the griping (from both the new hires and the hiring managers), and they in turn talk about the organization’s failures. This is a good thing; managers should clean up those processes to take wasted cost out and improve the experience for the new hire and the hiring manager. Still, we have not seen many companies truly do the basics well, and as a result some low hanging fruit is sitting there for the taking. But we want to repeat again, don’t fool yourself or your team. Improving Week One administration won’t materially impact retention and productivity. If new hires are aligned on objectives, love their jobs, find the work fulfilling, enjoy their manager, are inspired by career opportunities, and understand the culture, they will without any question forgive the company for not performing optimally on Week One administration.

As we have stressed throughout this book, proper onboarding administration goes way beyond the largely one-time only, transactional activities of Week One. If you have a mentoring component of your onboarding program, you’ll need to administer this component on an ongoing basis (assignments, content, direction, oversight, timing, etc.). Every time a new hire gets a mentor, the mentor requires notification and information about the mentee’s background and the desired mentoring focus. Recruiting managers always know things about the new hire’s point of view coming into the organization, but in most companies today nobody captures this information and effectively (and routinely) provides it to the mentor or, worse, the hiring manager.

In a well-administered mentoring program, a process will exist to collect information from the recruiter and hiring manager, store it in a centralized place (perhaps by leveraging existing software systems), offer it to the mentor alongside guidelines for how to run mentoring meetings, automatically schedule mentoring meetings on an ongoing basis, and dispense reminder notices as appropriate. This process would also organize more formal meetings at the key check points (e.g., 90-day, six-month, nine-month, and annual reviews), instructing mentors to discuss the culture and discuss development opportunities for the new hire, both in areas where the new hire needs to improve and in areas of special interest to the new hire. Without this process, the program will underperform (and from our experience, it will materially underperform). On the other hand, a well-administered mentoring process can provide a great experience from the outset, getting new hires off to a positive start at the company. As mentoring goes, leading corporations are increasingly doing a number of things to systematize effective mentoring, including:

• Putting formal programs in place to identify at risk (those that risk failing but should not) and high performing individuals (those with great prospects, so long as the organization does not fail them);

• Mandating frequent mentor meetings during onboarding to handle new hire concerns and monitor progress;

• Creating “mentoring circles” that provide multidirectional flows and feedback loops, thus expanding the perspectives available to a new hire; creating vertical, multi-generational “mentoring families” to mitigate the possibility of poor mentoring;

• Using goal and strengths input to align mentors with mentees, thus improving engagement of both by creating a sense of unique “fit” from the first day; and

• Providing guidance to mentors on the issues that they need to be discussing, the timing of the discussions, and the actions that they should take.

Mentoring is just the beginning. Almost everything we’ve covered in the last four chapters requires ongoing and thoughtful administration—performance management, task assignment, team assignment, pulse checks, buddy programs, affinity groups, networking events, and content updating on the web site and other media. In addition, program administration supports the systemic nature of onboarding over an extended period. Mentoring and buddy programs, for instance, need to unfold seamlessly in conjunction with the new hire networking program. Content across the organization needs to be updated and disseminated periodically and appropriately so that it is up-to-date. One of the senior leaders in an organization we once worked with opened a presentation to new hires with, “Well, I’ve never done this before, and they didn’t give me any materials, so I’ll just wing it.” In a world-class onboarding program, just like a world-class assembly plant or retail center, “winging it” doesn’t cut it; firms need infrastructure in place to ensure that people and processes across the organization are coordinated and have the fresh, high-quality material they need, when they need it.

Companies need to coordinate mentoring with ongoing learning and development events. They need a system that determines new hires’ learning needs and matches them to the resources, and the mentor needs to be part of this process. Such a system will assure on an ongoing basis that the firm possesses the right resources to meet new hire needs. Timelines and centralized checklists for development opportunities will be sent out to new hires, and completed courses will be automatically entered into the new hire’s profile for later reference. Reminders will be sent out to new hires and their hiring managers. All of this is plenty of work, yet if the proper resources are not there, the firm’s investment in mentoring and learning and development programs does not provide nearly as great a return as it might otherwise.

To give you a sense of the myriad administrative tasks required to execute a state-of-the-art onboarding program, imagine you are sitting down with a new hire and explaining to him or her all the elements of the redefined employee compact that you are promising to provide. As an important aside, we strongly suggest that you take this step; i.e., have actual conversations about this with new hires so that they fully understand and appreciate the commitment the firm is making on their behalf, as well as the responsibilities that they, the new hires, accept when entering the compact. Even a partial list of the firm’s promises as part of the employer-employee compact suggests the breadth of the administrative burden that accrues during onboarding:

The Firm’s Initial Promise to the New Hire

• We will provide you with the tools you need to get the job done: A computer, a work space, a phone/phone number, email, supplies, tools, equipment, safety equipment (personal protection equipment), etc.

• We will ensure that (if offered) benefits are handled smoothly.

• We will ensure that your new manager (and team) are ready for your arrival.

• We will assure you that a manager who oversees the onboarding program is available to answer questions that may arise.

• We will provide you with an onboarding buddy—someone who is at your level or is not long from having been a new hire themselves to help shepherd you through the process and serve as a resource for questions.

• We will provide you with knowledge about company learning and development resources at your disposal for establishing your career and setting out your career development.

• We will help you make connections with others in the company so that you can hear from others their “secrets of success,” make connections that may help you with your job performance, help you understand the strategies of the company and how the various units support each other in execution of those strategies, and make friends with similar professional and extracurricular interests.

• We will help you get settled in this new city—where to live, where to “play,” and how to meet others outside of our company who are in your industry.

• We will tell you how your role fits into the big picture: What the company strategy is and how you support it, who the various role players within the company are and how they support successful execution of the strategy, how and why our strategy differs from that of the competition, and what this means for you.

• We will provide you with progressive work assignments, so that you can achieve gradual success and make steps to achieve your personal prospect.

• We will provide you with regular “pulse checks” throughout your first year to find out how you are doing—how you are acclimating, how you experience your role and your network, how your understanding of your role and the strategy is progressing, and how we are doing in delivering on the promises we made to you during recruiting and Week One.

• We will provide you with many opportunities to learn company culture and strategy and to interact with other professionals. These opportunities will range from formal “traditional classroom” type training to “on demand” training you can access via Inter/Intranet, to mentoring, small group discussions and networking, net forums and blogs, and one-on-one conversations.

Now, these are pretty significant promises! Few if any firms possess an onboarding department, but looking at the preceding list, you quickly realize why such a department might be desirable. Of course, if your firm lacks resources for an entire department, you can always limit the workload by prioritizing which onboarding elements your firm offers and assigning responsibility to an existing entity within your organization. But the key is that it does become an expressed responsibility for that organization and/or individuals. All program elements require at least some level of administration, so the administrative resources (and supplemental external resources) you have available will help determine your firm’s priorities and the depth and breadth of your program. More on this in the next chapter on diagnostics.

Managing Administration Properly

To manage administration properly, we recommend that you implement a Provisioning and Administrative Support process that runs from the hour of offer acceptance all the way through the greater of the new hire’s entire first year or complete business cycle. This process needs to include all the materials and support necessary for a new hire to work well in his or her position. Certain materials, such as laptops and badges, should be ready by Day One, whereas others such as site-specific supplies and support will be provided later. Still other materials, such as reminders and organization for the performance review process, mentor meetings, learning and development activities, the remediation of at-risk employees, benefit support, and other program elements should run continuously.

Firms should take care to account for all of the “behind the scenes” activities that need to take place so as to support program execution throughout Year One. They should develop process flows and checklists to provide process owners with the necessary tools, guidance, and support to execute new hire activities during each program phase. To ensure that administrative processes do not get lost in the course of rolling out various phases of an onboarding program, these processes should be laid out explicitly as part of the formal program blueprint described in the next chapter, and they should run concurrently with all phases of the onboarding program. Writing administration into the blueprint formally recognizes logistical support needs and provides insight into possible provisioning gaps in the various phases. It also enables seamless process hand-offs across the four phases, all the way from Prepare to Excel, thus ensuring consistent support for new hires throughout the first year.

State of the art administration does not just involve planning and allocating for logistics and coordination; it also means deploying technology. To handle some administrative tasks, many firms have turned to off-the-shelf—and to some extent customizable—onboarding software. Software is great at helping firms arrive at a standardized approach for common tasks. Software packages vary, with many of them also serving as platforms for distributing learning materials to new hires, hiring managers, and other stakeholders. Some packages automate only certain relatively simple processes, such as providing benefits information or allowing new hires to fill out and submit forms for procedures such as obtaining a security badge. More sophisticated software might handle onboarding activities throughout an entire year, managing workflow and keeping managers and new hires on schedule with key onboarding activities such as mentoring meetings.

Evidence suggests that integrated talent management software suites can offer large gains when applied to onboarding, streamlining processes and seamlessly transitioning new hires to the rest of the talent management software. A 2007 Towers Perrin presentation cited that one major US telecommunications company used technology to onboard 12,000 new employees in just four weeks. The onboarding process began far in advance of the new employees’ first days of work thanks to online tools that automated traditional paperwork, saving the company time and money. In addition, new employees were able to begin acclimating themselves to their new work environment, developing a sense of excitement and engagement. As the 12,000 employees began work, the software they had begun using before their first day became their portal for all training, performance management, and promotion planning. The integrated software suite quickly assimilated new employees and took some of the burden off the company’s onboarding team.

Onboarding leaders such as Starwood, Starbucks, and Booz Allen use software to manage onboarding processes. Starbucks’ deployed system includes automation of administrative processes; training and orientation roadmaps; web-based portals for new hires, HR/administrative staff, and managers; and reporting of key analytics. The career planning tool offers individual new hire career profiles detailing goals and experience, integrated with destination planning roadmaps, manager inputs into employee profiles for additional talent assessment and management, and site-building tools to promote and match internal career opportunities to employees. The software allows for many advantages, including improved time-to-productivity, forms efficiency, better ability to track metrics, and scalability without the need for significant additional resources. It has been reported that Starbucks saw a 1 to 2 percent improvement in retention following implementation of the software and the associated support practices.

Other software platforms feature onboarding and career planning modules that integrate with other human capital life cycle modules; e.g., automated recruiting processes. The software includes analytics and measurement of new hire orientation activities, process map development tools for activities automation, and implementation best practices. Client constructed as well as commercial software include features that provide design and implementation tools for identifying and developing top performers, workforce management tools to redeploy internal talent, career path planning tools, and a “talent record” database that details development and performance information for each new hire. This database allows HR managers to search for internal candidate matches when positions open up, and it also includes tracking and reporting tools. Overall, the software allows for much greater efficiency in the performance of administrative tasks, especially as relates to the transition from recruiting, new hire documentation, and internal candidate searches. The software is fairly easy to implement and is compatible with many current systems. Since commercial packages have already been created, HR staff can focus on other, higher value tasks with a more strategic focus rather than designing a new program from scratch. Various packages offer different levels of customization and flexibility. Of course, many clients elect to develop platforms internally, providing for even greater degrees of customization.

Our own clients have had great success in automating parts of their onboarding programs, particularly by front-loading many normal Day One or Week One administrative activities before Day One—what we often call “pre-start” or “pre-boarding” in the Prepare phase. Time to productivity increases because the firm can start working on other key onboarding components, such as strategic education or networking, on Day One rather than spending time on benefits or other “basic” elements that have been pushed forward to a pre-start time frame. There is greater compliance and a more complete “paper trail” with these online delivered processes. Also, having new hires engage with the firm (and accomplish both pre-start work and learning) can further excite the new hire about the new job in the days and weeks before starting and allow you to more effectively “prime the pump” and hit the ground running. Software can also engage new hires by helping them to plan for and even establish cohort and other relationships of interest before Day One via social networking.

The key element of onboarding automation, especially as relates to pre-boarding, is the new hire portal. Access to an online portal can facilitate logistics, educate the new hire about the firm, make a new hire feel welcome and connected, and outline what to expect on Day One and beyond. Companies should conceive of the new hire portal as a core tool used throughout the first year and transitioning into other development tools as Year Two approaches. Although all portals will have a back-end interface for system administrators, the most effective portals will have interfaces (e.g., emails, alerts, planning and background tools, guides, etc.) for all core participants of the onboarding program (e.g., hiring manager, facilities, security, IT, mentors, etc.).

Upon offer acceptance, the portal needs to excite new hires by articulating what is in store for them at the company. The portal should expose new hires to all the development tools the company will provide. It should also provide guidance as to how to hit the ground running and how to increase chances for success. Positive as well as negative case study profiles really work well here. Cultural acclimation, perhaps in the form of blogs or video addresses from the CEO, should appear, as well as social networking features, initial training modules, and forms management. Companies can also post helpful items such as schedules, important phone numbers, and go-to resources.

Throughout Year One, intranet portals should provide links to all resources for addressing new hire needs, including instruction on how to resolve common problems and challenges encountered early in one’s career, guidance on development planning and training curricula, and reminders for key milestones and events. In other content areas, the portal should conform closely to new hires’ interests. The portal should cover professional and personal interests associated with joining the firm, such as information about where to live, school systems, how to find resources of interest, etc. Finally, the portal should express the brand of the onboarding program, maintain an authentic voice, and instruct the new hire on his or her responsibility for helping to assure the program’s positive outcome.

In addition to content, firms should consider the messaging, rich media elements, and functionality of portal sites for new hires. If the site is not dynamic and if there is not value and a sense of activity and community, it will likely not receive much traffic or attention beyond that which is necessary to complete required paperwork and tasks.

Governance Structures

If companies require proper administrative resources to reap onboarding’s full value, they also require governance and accountability mechanisms to ensure that the program works as intended. Without administrative resources in place, you’re leaving money on the table. If you have administrative resources without a governing and accountability mechanism, then everything you’ve tried to build is at risk. You may have the ability to execute processes, but you’ll be doing the same thing again and again without reviewing it to know if it’s working (i.e., meeting the original objectives, let alone the most current objectives). We have seen firms waste large dollars by failing to build a governance component into their onboarding program. More often than not, companies do not hold anybody accountable for onboarding, in large part because no single department oversees the whole program. These companies pull together cross-functional teams, which is great on the front end from a diagnostic and design perspective but ultimately insufficient from an oversight and management perspective. Exceptions do exist; we’ve seen companies that maintain piece part accountability; e.g., holding IT accountable for delivering computers or phones on time. Yet limited accountability comprises a mere shadow of what companies should implement so as to reap the full Onboarding Margin described in Chapter One.

Proper governance requires that as a first step you designate individuals with clear governing authority. We recommend a governance model with clear roles and accountabilities. A steering committee might provide strategic oversight, while below it an onboarding Center of Excellence might oversee programs and keep on eye on how well participants are performing and the return stakeholders are receiving. The Center of Excellence should also monitor content and delivery, including the ongoing development and updating of program curriculum and portal content. Companies should designate an “Authenticity or Integrity Czar”—a person who understands and encourages frank and genuine communication (e.g., calling the aspirational just that instead of portraying the aspirational as the “here and now”).

Below both of these groups, local onboarding coordinators should take charge of coordinating orientation for local offices and teams, ensuring that the new hire’s team and broader community is prepared to support key activities. Local onboarding coordinators also are tasked with reminding support personnel and ensuring compliance with key activities, such as networking and mentoring. A second group reporting into the Center of Excellence, regional onboarding coordinators, oversees firmwide orientation activities; schedules learning and development facilitators, senior leaders, and panelists; and coordinates any community events (e.g., “New Hire Summits” or networking events within the industry). A third group, Provisioning, provides access to the new hire portal and prepares equipment, other tools of the trade, and access to resources (including security access to the building) for Day One and beyond. A fourth group attends to the unique design elements that exist for new hire segmentation (e.g., by level and experience, but business unit, by geography, etc.).

Learning centers of governance structures

Some firms make use of corporate universities and learning centers as a means of centralizing the training portions of onboarding under a single authority. At these firms, corporate universities become the hub for resources and training relevant to new hires, providing early opportunities for employees interested in learning and development. New hires gain access to coursework supporting their career development through leadership courses taught by senior management and other “guidance-counselor” based models. This approach demonstrates commitment to new hire development, and the centralized governance structure allows for more resource delivery than programs fragmented across departments or business units. Interaction between new hires and senior leadership instructors provide networking and stronger relationships across levels. New hires are also able to network with seasoned employees in shared courses.

Setting up a structure like this does require a significant investment in additional learning resources as well as reorganization of career support functions into a central organization. We recommend that you make employee participation in coursework mandatory, and that feedback loops exist between university and senior leadership (to align with business goals) and between the university and new hire managers (to capture learning needs). Mandatory participation puts more pressure on designers to create coursework that is relevant, effective, and valued by new hires, hiring managers, and peers. Without proper resources and attention to relevance, you run a great risk of wasting valuable company resources.

Real-life examples of governance structures

At equipment manufacturer Caterpillar, the corporate university is tasked with identifying and meeting new hire learning needs. Departmental learning managers develop learning plans and maintain dual reporting relationships with the departmental HR officer and Caterpillar University, while the University offers mentor and career coach training. Clearly defined training centers help engage new hires in career development and offer them the possibility of continued advancement, learning, and career progression. The firm’s Leadership Quest onboarding program, available to selected management recruits, is predominantly taught by senior executives and tasked with the mission of helping young leaders understand Caterpillar’s global market and its challenges early in their careers. Pilot implementation of Caterpillar University’s “Making Great Leaders” program was so successful that it was rolled out among all 7,000 of the company’s leaders.

At Lockheed Martin, the corporate university—called the Center for Leadership Excellence—serves as the central training facility for new hires. Six levels of curriculum address all employees’ needs, from new hires up to senior leadership. Participant evaluations measure quality and ensure high standards (presenters scoring less than 4.5 out of 5 are not invited back). Learning is tied to mandatory training for specific programs, and an employee’s review processes evaluate training progress and program eligibility.

Another governance structure modification made by some leading edge onboarding programs involves designation of a team within the governance structure to handle issues associated with the employer brand. Starbucks ensures a maximum return on process improvements through its Employer Branding team. With expertise in branding, HR, and onboarding, the team develops a branded strategy to provide a unique onboarding experience and ensures that the “Starbucks Experience” is a strong brand externally as well as internally. Employer Branding representatives attend staffing and development planning meetings to ensure maximum ROI for new program rollouts. The group monitors the employer brand and considers branding ramifications of all process improvements, with an eye toward not merely preventing damage to the brand, but finding new ways to maximize benefits.

Starbuck’s Employer Branding team reflects the firm’s recognition of the significant retention value of appearing as a “best-in-class” employer. Employer branding establishes a sense of prestige that motivates individuals not merely to work at the company, but to stay there. As you think about governance of your employer brand, consider the segmented audiences that exist. You will need to maintain an overall umbrella employer brand and also have the opportunity to engineer unique brands for important new hire segments (e.g., front line hires, campus hires, manager hires, executive hires, etc.).

Measuring Onboarding Success

Beyond implementing a proper structure of oversight and accountability, governing an onboarding program entails mobilizing measurement tools and processes to determine if program elements are performing as desired (effective against the objectives and at the expected pace). If your firm judges it critical to have a certain program element, and if all new hires participate in this part of the program, then you need to measure the program’s performance by department, geography, and level. Otherwise, you have no way of knowing what needs improvement, nor can you determine the shortfall’s underlying cause. Even if your company is realizing desired results, you need to confirm that the program element has produced the benefit as opposed to some other factor. It is a completely inappropriate use of resources to continue investing in something if it isn’t creating the desired outcome.

In designing measurement systems, we advise measuring performance levels in ways that reflect the new hire’s perspective and that of the hiring manager (and for senior managers and executives, that of their peers). Again, companies only hire people to help managers get a job done. If hiring managers do not see greater new hire effectiveness, then onboarding is not working. We might be offering new hires a more attractive employer-employee compact, but fundamentally, we’re not doing onboarding to make people happy—we are doing it to improve enterprise performance. If we do not see improved enterprise performance, then there’s no improvement and no reason to do onboarding.

Impressions matter. Individuals other than the new hire community will interpret your onboarding brand. If hiring managers don’t believe onboarding delivers serious outcomes, they will see this as just another administrative task, and they will not participate or encourage new hires to participate. Onboarding program designers need hiring managers’ buy-in, so they should create a metric system around their needs. Also, firms should continually improve and update the onboarding programs; that way, hiring managers will continue to see the program as productive and remain excited about participating and supporting it.

As management guru Peter Drucker promoted, “What gets measured, gets managed.” As onboarding continues to grow as an HR management discipline, expectations to measure performance are increasing. Specific metrics tracked by onboarding leaders across organizations can and should vary depending on companies’ unique onboarding program objectives. Many companies are relying on both qualitative (surveys, focus groups, etc.) measures and quantitative (cost-savings) measures and blends of the two (perceived time to productivity) to assess the value created through onboarding.

In addition to enterprise-level metrics, more advanced onboarding programs apply metrics to employees responsible for delivering program components. Programs committed to measuring success and ensuring accountability are also developing metrics for each group of onboarding team members. These data prove invaluable for identifying areas of strength and opportunities for improvement.

As stated earlier, one of the onboarding Program Manager’s chief responsibilities is to monitor program performance and ensure that the enhanced program is meeting intended objectives across the organization. Often the program will require tweaking in a few areas post-implementation, and it will most certainly require periodic updates to meet changing organizational priorities. By the pilot stage, the organization should already have new hire and new hire manager surveys in place as well as initial baseline measures to monitor program effectiveness and satisfaction. Although these will prove important inputs, leading programs typically track a number of additional metrics and indicators—data that surveys cannot necessarily glean.

The metrics tracked by your organization will depend on your program’s organizational objectives. If your program seeks to increase your ability to recruit top talent from undergraduate programs, one metric you may want to track is intern conversion yield; i.e., the percentage of interns who receive and accept an employment offer. If your initial diagnostic revealed that new hires maintain a low level of connectedness with other employees in the organization, you may want to track how designed networking activities in the enhanced program impact new hires’ feeling of connectedness at several key points throughout the year.

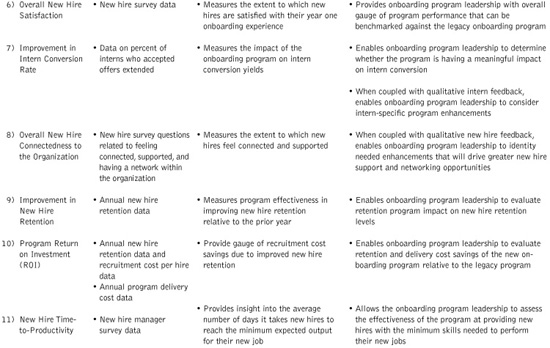

Before implementation, you should consider the full range of data needed to measure program performance, and you should ensure that you possess the proper mechanisms to gather this information on an iterative basis. Although this list does not necessarily contain all of the metrics your organization should track, onboarding metrics tend to fall into the following key categories noted in Table 7.1, and each can be segmented by new hire business unit (BU), function, and level.

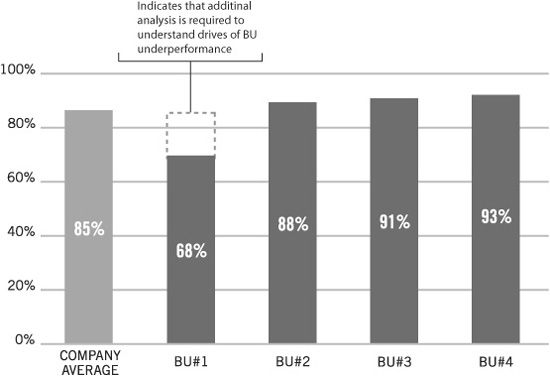

Numerous methods exist to view metrics so as to examine performance comparatively across the organization. Taking new hire Onboarding Satisfaction as an example, managers often find it most meaningful and actionable to focus on groups. These inter-organizational comparisons allow the Program Manager(s) to identify particular types of new hires who may be having a below average experience, as depicted in Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1 New Hire Satisfaction by Business Unit

Table 7.1 Sample Metrics Dashboard Approach

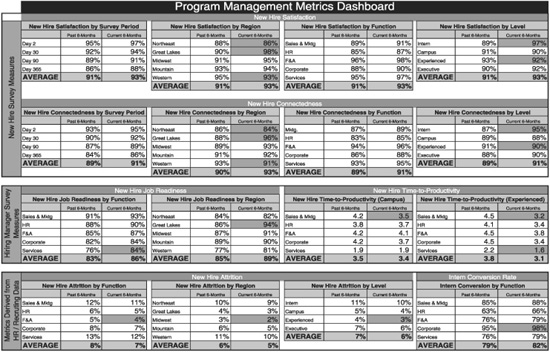

Before Implementation, the program manager should have a clear plan in place for gathering data on a quarterly or semi-annual basis, as well as a performance dashboard that rolls up the relevant data cuts for easy comparison and analysis. As an example of a dashboard, CheckFree, a provider of electronic services to the financial industry and today a part of Fiserve, has implemented an “onboarding excellence scorecard” measuring “efficiency, quality and attrition, process completion, and associate satisfaction during all phases of onboarding.” The system divides onboarding elements into distinct tracks (e.g., recruitment production, transition and mentoring, retention), and each month process improvements are generated for each track to drive onboarding metrics.2

Figure 7.2 provides an example of a metrics dashboard that links and forms the relevant data cuts for the Program Manager.

In developing metrics and a performance dashboard, onboarding designers should assign responsibility to individual participants for each metric, thus tying key onboarding players, including managers, mentors, and trainers, to the broader onboarding program’s success. New hire tasks and objectives should also be clearly defined and tracked as a metric. Onboarding objectives and timelines should be codified for all new hires, while managers should collaborate with each new hire on an individual basis to define specific onboarding objectives and chart the new hire’s career development progress. Ownership and responsibilities should be clearly defined, and a new hire’s performance against his or her onboarding objectives should help comprise a basis for early career performance evaluation. As we noted when discussing early career support, it is important for the new hire to demonstrate progress over the course of his or her first year as a key element of the new hire’s development.

Companies should also hold hiring managers, human resources, and other key players accountable for the completion of objectives. Objective completion and execution rates should be treated as a metric for assessing the success of the entire onboarding program, as this ties program success to the individual onboarding objectives of each new hire, providing for personalization of experience and allowing new hires to attain desired onboarding goals in a proactive way. Onboarding responsibilities should be written into the job descriptions of the role participants and should comprise part of each participant’s general formal performance assessments. In a lesser way, an onboarding element should also be written into the job responsibilities of all senior employees who interface with new hires. To be systemic, onboarding needs to be part of the organization’s fiber, and for that to happen, established employees need to bring the “onboarding ethic” and values to life. Unless formal responsibilities clearly address onboarding, this process risks devolving into a rote exercise with little meaning or impact.

Figure 7.2 Sample Metrics Dashboard Tracking Sheet

Integrated process automation and tracking software can support the efficiency and effectiveness of metric evaluation. HR can input training completion and training rates, while web-based self-assessment tools for new hires help monitor productivity/capability assessments, objective tracking and completion rate, equipment receipt, and satisfaction surveys. Starbucks uses its onboarding software suite to track metrics like Time to Complete Training, Time to Capability, Time to Receiving Equipment and Tools, and Retention. The telecommunications company Sprint Nextel uses automated reporting software to track metrics such as the following:

First-year Retention,

Time to Training Completion,

Time to Productivity, and

Time to Receiving Needed Equipment and Tools.

Senior management monitors these metrics regularly and reviews them annually, setting objectives for the following year. As a result of the implementation and tracking of key performance metrics, Sprint Nextel has seen a stronger onboarding program that has driven quicker productivity and higher retention. Time to productivity has decreased by more than 30%, and retention rates have risen by more than 20%.

Incorporating onboarding into existing feedback mechanisms, such as departmental and annual corporate surveys, can provide important insights from untapped sources. Drawing opinions from a broader pool of participants provides greater perspective on the role of onboarding in the corporation and increases awareness. It also elicits feedback and ideas that may otherwise be overlooked.

HR might insert questions directly pertaining to new hires, such as, “Was your computer delivered before you arrived?” or “If you could change one thing about the onboarding experience during your first year, what would you change?” Tenured employees might be asked, “In your experience, how prepared have new hires been for their jobs?” and “What could be done to better prepare new hires for a job in your department?” To quantify performance, you should structure questions for scoring along a low to high answer set spectrum, you should render sample sizes large enough to cover each employee segment in a statistically significant way, and you should take measures on a regular basis, allowing for comparative results and trend analysis.

Using feedback to measure success

Best-in-class onboarding firms have developed innovative techniques for gaining regular and actionable feedback data. Starbucks promotes open, employee-initiated communication about onboarding; new hires can provide feedback, express concerns, or request new programs through Starbucks’ Mission Review System, which guarantees employees a response. Similarly, any new hire can write the CEO and receive a guaranteed response. Starbucks invests in this form of feedback on the belief that employees who feel they can express their beliefs will prove less likely to become frustrated and quit. “We realized that as we grew we increasingly needed to hire different types of employees, mainly corporate employees,” one Starbucks program manager told us, “and we found that these communication tools were some of the best ways to ensure that their needs were being met.” Use of employee-initiated feedback helps uncover process improvements by tapping the ideas and feedback of all new hires. It also helps boost Starbucks’ employer brand higher, since communication serves as the main driver behind such employer brand rankings.

Verizon Wireless measures individual feedback as the chief determinant of onboarding program success. The company queries new hires before onboarding about their expectations and then surveys them during and upon completion of the program. The firm also uses town hall meetings and web seminars to identify process gaps. Unlike most firms, Verizon views onboarding process development as an organic experience that should evolve so as not to remain stagnant. HR monitors feedback on a monthly, quarterly, and yearly basis, using permanent feedback mechanisms to improve onboarding experience continuously. Measurement of individual feedback in this way increases responsiveness, provides the means for change, and also provides a means for testing pilot programs. Of course, for this to work a firm needs permanent feedback mechanisms as well as tools sufficient to collect and interpret feedback.

Finally, General Mills ensures the responsiveness of its onboarding program by fielding frequent and regular surveys as a component of company-wide climate surveys. Corporate-wide results are gathered every two years and used to plan new program rollouts. Progress in addressing concerns raised during the corporate-wide survey are evaluated with more focused status updates in the off-year when a complete survey is not taken. Departmental climate surveys are conducted more often as required by departmental needs to gather more specific insights. Surveys include questions about onboarding effectiveness, career support, planning programs, and training needs. The firm also gauges onboarding through new hire process evaluations at the end of each onboarding phase. All of this yields a responsive and constantly improving program. It allows for new hire input, and it also ensures that the mechanisms for change remain in place, allowing for early adoption of innovative practices. Measuring program performance in this way requires a survey infrastructure, tools to conduct status reports, and tools to track changes in survey results.

Summing Up

Onboarding administration and governance might not be sexy, and by themselves these elements will not provide the big value boost that onboarding as a whole promises. Yet administration and governance underlie the success of any program and comprise a vital part of the new employer-employee compact that firms can and should offer through onboarding. To realize the Onboarding Margin, the onboarding experience and program must be systemic; this means firms must implement the administrative means to coordinate stakeholders and take actions across the firm, and they should also implement the mechanism for assuring compliance and continuous improvement in the program’s workings.

As consultants, we have witnessed too many initiatives fly out of the gate only to falter for lack of sufficient administrative resources. Often a project team is assigned to develop a process, and then the team disbands for the next assignment without leaving resources in place to maintain the program with up-to-date information about strategy, organizational structure, resources available, etc. By contrast, best-in-class firms assign people with senior authority, experience, and knowledge to determine if everything is aligned, and they also put mechanisms in place to upgrade the program as necessary. Someone must do these things; otherwise, they do not get done, and programs suffer.

We have examined the four pillars covered by our model for successful onboarding as well as the underlying organizational requirements for bringing them to new hires. Yet deciding which program elements to include, how precisely to execute them, how to link them to one another, when to roll them out, and who to involve is by no means an easy task. Given limited resources, how should a firm weave onboarding elements together in a way best suited to the organization and its own strategic goals? The two chapters that follow outline a process for successfully conceiving, designing, and selling in a strategic onboarding system. We start in the next chapter with what we regard as that ever-important, but frequently neglected, initial phase, diagnostic investigation and analysis.